Lipidated COVID-19: Mitochondrial Impact and Long COVID

Lipidated COVID-19 Localizes into Mitochondria and Causes Oxidative Damage to Mitochondrial DNA–Pathophysiology of long COVID

Moragot Chatatikun 1,2†, Hiroko P. Indo 3,4†, Motoki Imai 5–7, Fumitaka Kawakami 5–9, Makoto Kubo 7,10, Takafumi Ichikawa 7,8, Hiroshi Abe 3, Jun Urano 11, Fuyuhiko Tamanoi 12, Warinda Prommachote 1,13, Suriyan Sukati 1,13, Jirapat Namkeaw 14,15, Thiranut Jaroonwitchawan 14,15, Hiroshi Ichikawa 16, Voravuth Somsak 1,2, Jitbanjong Tangpong 1,2, Sachiyo Nomura 17-19 and Hideyuki J. Majima 1,2

† Those authors contributed equally on this paper.

- Hideyuki J. Majima School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat, 80161, Thailand; Research Excellence Center for Innovation and Health Products (RECIHP), School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80160, Thailand

- Moragot Chatatikun School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat, 80161, Thailand; Research Excellence Center for Innovation and Health Products (RECIHP), School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80160, Thailand

- Hiroko P. Indo Department of Oncology, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima City, Kagoshima 890-8544, Japan; Amanogawa Galactic Astronomy Research Center (AGARC), Kagoshima University Graduate School of Sciences and Engineering, 1-21-40 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan

- Motoki Imai Department of Molecular Diagnostics, School of Allied Health Sciences, Kitasato University, 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara 252-0373, Japan; Department of Applied Tumor Pathology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kitasato University, , 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara 252-0374, Japan; Regenerative Medicine and Cell Design Research Facility, School of Allied Health Sciences, Kitasato University, 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara, 252-0373, Japan

- Fumitaka Kawakami Department of Molecular Diagnostics, School of Allied Health Sciences, Kitasato University, 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara 252-0373, Japan; Department of Applied Tumor Pathology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kitasato University, , 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara 252-0374, Japan; Regenerative Medicine and Cell Design Research Facility, School of Allied Health Sciences, Kitasato University, 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara, 252-0373, Japan; Department of Regulation Biochemistry, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kitasato University, 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara, 252-0373, Japan Department of Health Administration, School of Allied Health Sciences, Kitasato University, 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara, 252-0373, Japan

- Makoto Kubo Regenerative Medicine and Cell Design Research Facility, School of Allied Health Sciences, Kitasato University, 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara, 252-0373, Japan; Department of Environmental Microbiology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kitasato University, 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-0373, Japan

- Takafumi Ichikawa Regenerative Medicine and Cell Design Research Facility, School of Allied Health Sciences, Kitasato University, 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara, 252-0373, Japan; Department of Regulation Biochemistry, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kitasato University, 1-15-1 Kitasato, Minami-ku, Sagamihara, 252-0373, Japan

- Hiroshi Abe Department of Oncology, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima City, Kagoshima 890-8544, Japan

- Jun Urano Cellbre, San Diego, CA 92121, USA

- Fuyuhiko Tamanoi Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences, Institute for Advanced Study, Kyoto University Kyoto 606-8501 Japan

- Warinda Prommachote School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat, 80161, Thailand; Hematology and Transfusion Science Research Center (HTSRC), School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80160, Thailand

- Suriyan Sukati School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat, 80161, Thailand; Hematology and Transfusion Science Research Center (HTSRC), School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80160, Thailand

- Jirapat Namkeaw Futuristic Science Research Center, School of Science, Walailak University, Thasala, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80160, Thailand; Research Center for Theoretical Simulation and Applied Research in Bioscience and Sensing, Walailak University, Thasala, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80160, Thailand

- Thiranut Jaroonwitchawan Futuristic Science Research Center, School of Science, Walailak University, Thasala, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80160, Thailand; Research Center for Theoretical Simulation and Applied Research in Bioscience and Sensing, Walailak University, Thasala, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80160, Thailand

- Hiroshi Ichikawa Department of Medical Life Systems, Graduate School of Life and Medical Sciences, Doshishia University, Kyoto 610- 0394, Japan

- Voravuth Somsak School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat, 80161, Thailand; Research Excellence Center for Innovation and Health Products (RECIHP), School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80160, Thailand

- Jitbanjong Tangpong School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat, 80161, Thailand; Research Excellence Center for Innovation and Health Products (RECIHP), School of Allied Health Sciences, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80160, Thailand

- Sachiyo Nomura Department of Clinical Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Hoshi University, 2-4-41 Ebara, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo, 142-8501 Japan; Isotope Science Center, The University of Tokyo, 2-22-16 Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0032, Japa; Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The University of Tokyo Hospital, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8655, Japan

* Corresponding author (HJM)

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 January 2025

CITATION : Chatatikun, M., Indo, HP., et al., 2025. Lipidated COVID-19 Localizes into Mitochondria and Causes Oxidative Damage to Mitochondrial DNA–Pathophysiology of long COVID. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(1). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6157

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6157

ISSN: 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Protein lipidation modifies proteins in eukaryotic cells, including cysteine prenylation, and N-terminal glycine myristoylation, and regulates many biological pathways. We summarize the history of lipidation and the roles of prenylation, myristoylation, and palmitoylation. Lipidation modifies other molecules and takes them to the cellular membrane. Lipidized proteins also go to mitochondria. Prenylation links protein C end motif, and myristoylation links protein N end motif. Palmitoylation links protein C or N motif. It is possible to take both prenylation and myristoylation. Previously, we showed that HSP47 interacts with prenylated and myristoylated proteins, goes to mitochondria, and generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) from mitochondria. It is known that mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) further causes apoptosis and intra-mitochondrial damage to lipids, proteins, and mtDNA. Viral proteins are lipid-modified by infected cells and go to mitochondria, and the electron transport chain (ETC) generates further reactive oxygen species (ROS). The excess ROS may cause lipid peroxidation and damage to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). COVID-19, also prenylated and myristoylated, goes to mitochondria, generates mtROS, and damages mtDNA. It is the pathophysiology of long COVID.

Keywords:

mitochondria; lipidation; prenylation; myristoylation; palmitoylation; virus; HSP47

INTRODUCTION

Life appeared on Earth 3.8 billion years ago, when the atmosphere had almost no oxygen 1,2. A membrane surrounds cells, the components of which include lipids, and then cells can maintain their circumstances. Life has evolved to have organelles to share their functions inside cells. Cells must import many substances inside them. Stein described the detailed systems of cell membrane transport and diffusion 3. Most large molecules can’t cross cell membranes without their carriers. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) without electric charge across the membrane 4–7.

Oxidative phosphorylation produces ATPs via the electron transport chain (ETC), which is localized in the inner membrane of mitochondria. However, this biological machine is imperfect, and 2 – 3% of electrons leak during electron transportation. Oxygen molecules react with those electrons, producing superoxide anion (O2•-) in mitochondria, and O2•- produces several different ROS. The authors demonstrated that mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) caused apoptosis for the first time 8 and showed that mtROS initiates intracellular signals 5–7,9.

Heat shock protein-47 (HSP47) is present in the endoplasmic reticulum of cells and performs several functions regarding cartilage and bone formation, autophagy, and fibrosis 10,11. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) have their roles in protein and cellular signaling 12. Previously, we reported electron and X-ray irradiation can induce different changes in the protein via PTMs that lead to significant physiological and pathophysiological effects in the cells and tissues 13. We found that lipidated, farnesylated, and myristoylated HSP47 went to mitochondria and generated reactive oxygen species from mitochondria 13. We have shown mitochondria as the target of lipidation.

In this review, we describe the history of lipidation, the roles of prenylation, myristoylation, and palmitoylation, mitochondria as the target of protein lipidation, and viruses. We focus a new role on mitochondria as the target of viral lipidation. Then, the excess ROS generated from mitochondria may cause lipid peroxidation and further damage mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). These mtDNA damages will cause ‘long COVID’.

Unique properties of protein lipidation

HISTORY OF LIPIDATION

A lipid membrane surrounds the cell, shielding it from its environment 3. The membrane also functions to communicate with the exterior environment. The lipid components involved in this communication must be close to the hydrophobic cell membrane. However, most proteins are water-soluble. Protein lipidation, such as prenylation, myristylation, and palmitoylation, overcomes this obstacle.

Myristate and palmitate represent the most common fatty acid modifying groups. Each fatty acid manages distinct biochemical properties that regulate intracellular trafficking, subcellular localization, protein-protein, and protein-lipid interactions 14. Over the past two decades, protein S-acylation (S-palmitoylation) has emerged as an essential regulator of crucial signaling pathways. S-acylation is a reversible post-translational modification involving a fatty acid attachment to a cysteine residue of proteins through a thioester bond. The balance of protein S-acylation and deacylation has profoundly affected various cellular processes, including innate immunity, inflammation, glucose metabolism, and fat metabolism 15. Defects of prenylation promote the activation of inflammation and induce a dysfunction of mitochondrial activity and oxidative stress 16. Genetic and pharmacological manipulation of protein prenylation has provided insights into several cellular processes and the etiology of diseases involved in prenylation, such as interference of RAS protein prenylation and cancer17.

Protein lipidation, referring to lipid attachment to proteins, is prominent and occurs in many proteins in eukaryotic cells and regulates numerous biological pathways 18. Protein lipidation is a significant co- or post-translational modification that markedly increases the hydrophobicity of proteins, resulting in changes to their conformation, stability, membrane association, localization, trafficking, and binding affinity to their cofactors 19. These modifications increase proteins’ complexity and functional diversity in response to complex external stimuli and internal changes. Protein lipidations primarily encompass five types: S-prenylation, N-myristoylation, S-palmitoylation, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor, and cholesterylation. Yuan et al. described the timeline of protein lipidation research, regulatory enzymes, important protein substrates, clinical trials, and the development of inhibitors. They described the importance of these modifications for protein regulation, cell signaling, and diseases 20. They illustrated the timeline of protein lipidation research, including regulatory enzymes, important protein substrates, clinical trials, and the development of inhibitors. Proteins can be modified by at least seven types of lipids, including fatty acids, lipoic acids, isoprenoids, sterols, phospholipids, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors, and lipid-derived electrophiles (LDEs) 19,21. Numerous genetic, structural, and biomedical studies have consistently shown that protein lipidation is pivotal in regulating diverse physiological functions and is inextricably linked to various diseases 21. Furthermore, cellular lipid metabolism affects the availability of fatty acyl-CoA and other lipid derivatives used as substrates for protein lipidation. The 16-carbon fatty acid palmitate, is a critical intermediate for the biosynthesis of other cell lipids 19.

Roles of Prenylation, myristoylation, and palmitoylation

PRENYLATION

Roles of prenylation

Prenylation, the modification of eukaryotic proteins by isoprenoid lipids, controls the localization and activity of a range of proteins with critical functions. Protein prenylation is a ubiquitous covalent post-translational modification found in all eukaryotic cells, and the roles of prenylated proteins are well conserved across species. Wang and Casey highlighted this lipid modification pathway’s biological and evolutionary importance 17. Protein prenylation is a ubiquitous covalent post-translational modification found in all eukaryotic cells. It comprises the attachment of either a farnesyl or a geranylgeranyl isoprenoid. Prenylation is essential for the proper cellular activity of numerous proteins, including Ras family GTPases and heterotrimeric G-proteins. Inhibition of prenylation has been extensively investigated to suppress the activity of oncogenic Ras proteins to achieve antitumor activity 22.

Wang and Casey described the roles of prenylation on aging 17. There is considerable interest in targeting protein prenylation in premature aging disorders and understanding its role in normal aging. The final maturation step involves removing the C-terminal 15-amino-acid peptide by the endoprotease ZMPSTE24, which is dependent on prenylation. The most well-studied form of the premature aging disorder, Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), is caused by a genetic mutation of prelamin A that leads to alternative splicing and the consequent loss of the ZMPSTE24-recognition site 23. A more severe form of progeria is caused by a mutation resulting in the loss of ZMPSTE24 protease activity. In all forms of progeria, the resulting incompletely processed protein, termed progerin, accumulates on the nuclear envelope, triggering a range of molecular disturbances that lead to premature aging. Interestingly, the treatment of farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs) reverses the phenotypical abnormalities in progeroid cells 24,25, and the knock-in of a form of prelamin A that cannot be farnesylated in mice with the genetic background of progeria yielded relatively average survival 26. These studies led to a clinical trial using FTIs to treat progeroid syndromes. Although FTIs had only a modest effect on disease progression 27, the results prompted an ongoing trial using a combination of FTI with a statin and bisphosphonate compounds that affect the farnesyl biosynthesis pathway, and early data have shown that the triple-drug combination can reduce the multi-organ phenotype of aging and significantly prolong survival. Progress has also been made in investigating the effects of targeting isoprenylcysteine carboxymethyltransferase (ICMT), the enzyme that carries out the terminal carboxyl methylation after prenylation; introduction of a hypomorphic allele of ICMT into the Zmpste24 −/− mouse model of progeria largely rescued both the premature aging phenotype and premature death 17.

Discovery of protein prenyl groups and structural varieties

The posttranslational modification of proteins with lipid moieties, known as protein lipidation, was first recognized in the late 1970s and the beginning of 1980s 28. The discovery of protein S-prenylation was in 1978, S-palmitoylation was in 1979, and protein N-myristylation was in 1982 29. The first reports of prenylated proteins and peptides described the secreted pheromone peptides from yeasts 30,31. Sakagami et al. isolated a novel sex hormone tremerogen A-10 that controlled conjugation tube formation in Tremella mesenterica 32,33. Protein prenylation was also described by Kamiya et al. 34 and Ishibashi et al. 35.

Protein prenylation: C-terminal motifs

Protein prenylation involves the transfer of either a farnesyl or a geranylgeranyl moiety to C-terminal cysteine(s) of the target protein 36. The CaaX and C-seven motifs were found as C-terminal motifs for the prenylation 37. The CaaX motif consists of a cysteine (C), two aliphatic amino acids (“aa”), and if X position is serine, alanine, or methionine, the protein is farnesylated, or if X is a leucine, the protein is geranylgeranylated 38. The second motif for prenylation is CXC, which, in the Ras-related protein Rab3A, leads to geranylgeranylation on both cysteine residues and methyl esterification 38. The third motif, CC, is also found in Rab proteins, where it appears to direct only geranylgeranylation but not carboxyl methylation 38. Carboxyl methylation only occurs on prenylated proteins 38. Prenylation includes dimethylallylation (C5), geranylation (C10), farnesylation (C15), and geranylgeranylation (C20), depending on the number of isoprenyl (C) motifs 39 (Table 1).

Myristoylation

Myristoylation is the covalent attachment of a 14-carbon myristoyl group to the alpha-amino group of an N-terminal glycine residue via an amide bond 40. Myristoylation was first described in 1967 by Ochoa-Solano, Romero, and Gitler, who showed histidine lipidation by myristoylation 41.

N-myristoylation can occur both post-translationally and co-translationally. Co-translational N-myristoylation can influence the transport and localization of the protein, which likely affects the protein’s function 29. Yuan et al. highlight N-myristoylation’s numerous roles in normal cell physiology and human diseases like cancer and infection. Furthermore, inhibitors of N-myristoylation are being investigated to treat these diseases 29.

Palmitoylation

Palmitoylation, which modifies a protein with a 16-carbon palmitate, was discovered in the 1960s. Three types of palmitoylation have been described: S-palmitoylation, N-palmitoylation, and O-palmitoylation 21 (Table 1).

S-palmitoylation

S-palmitoylation is the reversible attachment of palmitic acid via a thioester bond on cysteine residues. Palmitoylation is carried out by palmitoyl acyltransferases (PATs, also known as ZDHHC-PATs) and acyl protein thioesterases (APTs) removes the palmitoyl group. PATs have a conserved cysteine-rich zinc-finger Asp-His-His-Cys (ZDHHC) motif in the catalytic domain and is essential for activity 21. Examples of proteins that are S-palmitoylated include the proto-oncogene GTPase NRas, cell surface death receptor Fas, apoptosis regulator BCL2-associated X (BAX), and the proto-oncogene non-receptor tyrosine kinase Src 21.

N-palmitoylation

The attachment of palmitic acid via an amide bond to the amino group of the N-terminal residue of a protein is N-palmitoylation. Attachment of palmitic acid can also occur on the ε-amino group of a lysine residue at the N-terminus, referred to as N-palmitoylation. An example of N-palmitoylation is human Sonic Hedgehog (SHh), which is palmitoylated on the amino group of the N-terminal cysteine residue by Hedgehog acyltransferase (HHAT) 21.

O-palmitoylation

In O-palmitoylation, palmitic acid is irreversibly linked to the side chain of serine residues through an ester bond. Only a handful of proteins have been reported to be O-palmitoylated. One example is histone H4, which is O-palmitoylated at Ser-45 by lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1 (LPCAT1) 42. In addition, the blocking of presynaptic voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by the spider venom PLTX-II is thought to be mediated by O-palmitoylation at a threonine residue in the C-terminal region of the neurotoxin 21.

Mitochondria as the target of protein lipidation

Mitochondria comprise 1,000 to 1,500 proteins 43. The protein import machinery of the mitochondrial membranes and aqueous compartments reveals a remarkable variability of protein recognition, translocation, and sorting mechanisms 44. The electron transport chain (ETC) is in the inner membrane, comprises nearly 100 proteins, and should be appropriately brought to ETC 45. Further, many proteins go outside and inside mitochondria to maintain homeostasis against physiological and pathological interference 46.

Mitochondrial lipids modulate protein import on various levels involving precursor targeting, membrane potential generation, stability, and activity of protein translocases 47. To reach mitochondria, proteins should be modified with lipidation 48.

Boveris and Navarro described reduced mitochondrial biogenesis as correlated with aging 42. Archaea use prenylated hemes as cofactors of cytochrome oxidases 21,49. In mitochondria, many components are prenylated, myristoylated, and palmitoylated; many are related to aging and diseases. For example, S-palmitoylation of Bax 50, and myristoylation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) 51. Kostiuk et al. identified 21 putative palmitoylated proteins in the rat liver mitochondrial matrix 52. Simvastatin treatment inhibits the biosynthesis of mevalonate, causing cytochrome c to be released from the mitochondria to the cytosol. This effect is associated with activation of caspase 9 and 3 during apoptosis. This effect was reversed by adding mevalonate, farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP), suggesting protein prenylation’s involvement in the apoptosis mechanisms 53.

It is known that some lipid-modified proteins go to mitochondria. Zha et al. demonstrated that Bid is N-myristoylated, goes to mitochondria and cause apoptosis 54. Utsumi et al. (2003) demonstrated that the C-terminal 15 kDa fragment of cytoskeletal actin is targeted to mitochondria via posttranslational N-myristoylation during apoptosis 55. Bivona et al. demonstrated that K-Ras, when phosphorylated by protein kinase C (PKC), rapidly dissociates from the plasma membrane and, through association with Bcl-XL on the outer mitochondria membrane, induces apoptosis 56. Beauchamp et al. demonstrated that N-myristoylation of dihydroceramide Delta4-desaturase 1 (DES1) results in targeting DES1 to the mitochondria, leading to an increase in ceramide levels, which contributes to the apoptosis effect of myristic acid, in COS-7 cells 57. Lynes et al. demonstrated that palmitoylation of calnexin serves to enrich calnexin on the mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM) 58. Palmitoylated calnexin interacts with sarcoendoplasmic reticulum and Ca2+ transport ATPase (SERCA) 2b, and this interaction determines ER Ca2+ content and the regulation of ER-mitochondria Ca2+ crosstalk. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) plays a central role in cellular energy sensing and bioenergetics. Liang et al. demonstrated that N-myristoylation of AMPKβ by the type-I N-myristoyl transferase 1 (NMT1) confers the recruitment of AMPK to the mitochondria 51. Bhat et al. showed that FBXO10, the interchangeable component of the cullin-RING-ligase 1 complex, is geranylgeranylated and localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane 59. These examples show that many lipid-modified proteins localize to the mitochondria and perform various critical functions.

Coenzyme Q (CoQ) is not protein, but CoQ or ubiquinone is a crucial lipid component of the electron transport chain and is required for ATP generation in mitochondria. CoQ is the generic name of a class of lipid-soluble electron carriers formed of a redox-active benzoquinone ring attached to a prenyl side chain 60. Mutations in CoQ biosynthetic genes are associated with rare but ROS infantile multisystemic diseases 61. CoQ10 supplementation rescues cerebellar ataxia with CoQ10 deficiency 62. CoQ10 supplementation rescues renal disease in Pdss2kd/kd mice with mutations in prenyl diphosphate synthase subunit 2 63.

Protein lipidation: Where do they go, the cellular membrane or mitochondria?

Jiang et al. published a review of protein lipidation 18. They described that protein lipidation, cysteine prenylation, N-terminal glycine myristoylation, cysteine palmitoylation, and serine and lysine fatty acylation occur on many proteins in eukaryotic cells. The lipid-modified proteins go to cellular membranes and regulate many biological pathways, such as membrane trafficking, protein secretion, signal transduction, and apoptosis 18. Jiang et al. posed several interesting questions: how can the same modification target different proteins to different organelles, e.g., N-terminal glycine myristoylation targets specific proteins to the mitochondria and others to the plasma membrane18. Do lipid modification and its local environment have an intrinsic affinity for different membranes, or are different trafficking machinery engaged by the modified proteins.

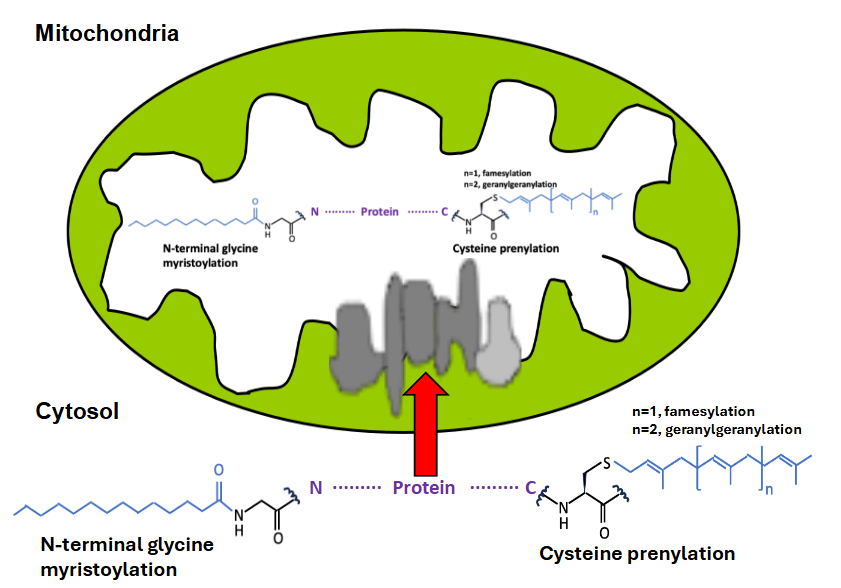

The difficulty might be the situation’s complexity, e.g., the existence of different trafficking machinery 18. Table 1 shows classifications of fatty acylation and their protein-modification sites. The modified residue of prenylation is Cys (C) in CaaX, CXC, and CC motif of C-terminal protein (Table 1) 39,40. At the same time, those of myristoylation is Gly (G), and Lys (K) of N-terminal protein, those of S-palmitoylation are Cys (C) of C-terminal protein, those of N-palmitoylation, O-palmitoylation are Lys (K) of C-terminal protein and Ser (S), Thr (T) of C-terminal protein, respectively. The modified residue of N-terminal palmitoylation is Cys (C) of N-terminal protein (Table 1) 12,19. C- and N-terminal modifications may quickly occur in cells and go to mitochondria (Figure 1).

Virus, lipidation and mitochondria

Viral proteins are also substrates for prenylation; viral proteins can be post-translationally modified by protein lipidation mechanisms of their host cells 64. Some inhibitors of prenylation exhibit potent antiviral activities 65.

Viral proteins containing the C-terminal CaaX motif can be prenylated by host prenyltransferases. A clinically relevant example is the large antigen of the hepatitis delta virus. Glenn et al. first demonstrated the evidence for the role of prenylation in viral replication 66. During replication, the hepatitis delta virus (HDV) switches from producing small to large delta antigens. Both antigen isoforms have an HDV genome binding domain and are packaged into hepatitis B virus (HBV)-derived envelopes but differ at their carboxy termini. The large antigen was shown to contain a terminal CXXX box and undergo prenylation 66. Bordier et al. found that prenylation inhibitors prevent infectious hepatitis delta virus particles 67 and found in vivo antiviral activity against hepatitis delta virus 67. The phase 2A clinical trial results showed that the prenylation inhibitor lonafarnib significantly reduces hepatitis delta virus levels 65.

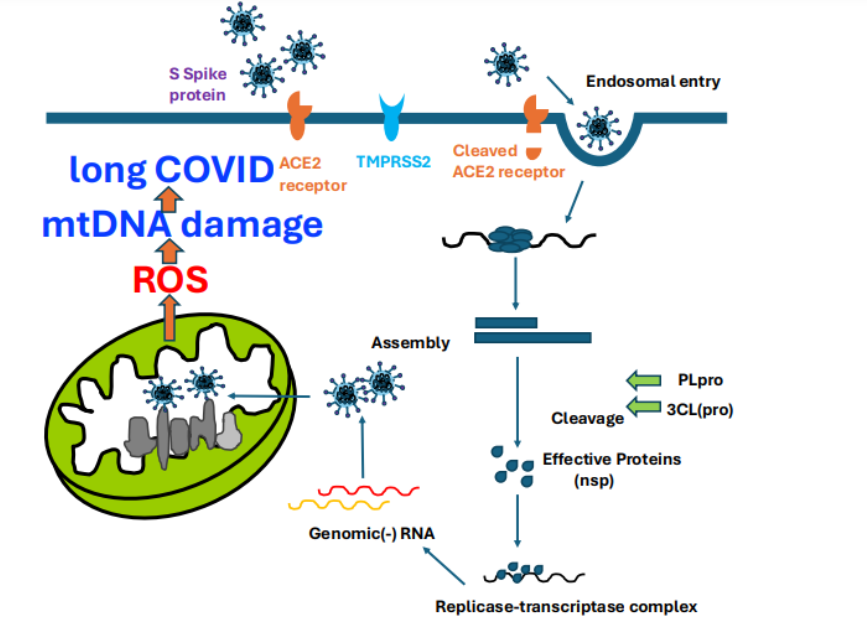

After infection with SARS-CoV-2, virus-derived proteins are produced inside the host cell 68. Zhou et al. described protein-protein interactions that comprise the SARS-CoV-2 and human protein interactome using high-throughput two-hybrid experiments and mass spectrometry 69. Viral proteins were found to be lipid-modified, and some viral proteins will be localized to the mitochondria. ROS are generated once the virus localizes in mitochondria, damaging mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Then, mtDNA will be more damaged and generate more ROS for an extended period. This will be a pathophysiology of “long COVID” (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Prenylation binds to the C-terminal end, while myristoylation binds to the N-terminal end of viral protein.

Figure 2: Prenylation binds to the C-terminal end, while myristoylation binds to the N-terminal end of viral protein.

Graphic Figure Legends: Prenylation binds to the C- terminal end, while myristoylation binds to the N-terminal end of proteins and virus-translated proteins. They go to mitochondria, bind to ETC, produce ROS, and further cause apoptosis or damage to mt DNA

CONCLUSION

Protein lipidation, including prenylation, myristoylation, and palmitoylation, targets proteins to various cellular membranes. Mitochondria, which have two membranes, are also target of protein lipidation. Previously, we showed that HSP47 is associated with prenylation and myristoylation, goes to mitochondria, and generates mtROS. It is known that mtROS further causes apoptosis and intra-mitochondrial damage to lipids, proteins, and mtDNA. Viral proteins are also modified by protein lipidation by the prenylation and myristoylation in host cells and localize to mitochondria, generating excess ROS and mitochondrial damage, including mtDNA. This is a story of ‘long COVID’.

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization, M.C., H.P.I., J.U., F.T. and H.J.M.; methodology, H.J.M.; software, H.A.; writing and validation, M.I., F.K. M.K., T.I., J.U., F.T., W.P., S.S., J.N., T.J., H.I., V.S., J.T., and S.N.; data curation, J.U., F.T., H.P.I., H.A., and H.J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C., H.P.I.; writing—review and editing, J.U., F.T., J.N., T.J., H.P.I., S.N., and H.J.M.; supervision, H.J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding:

This study was supported by the COVID-19 Kitasato project and a grant from Kitasato University School of Allied Health Sciences (Grant-in-Aid for Research Project, No. 2022-1013). Walailak University also contributed to this study.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments:

I, Hideyuki J. Majima, sincerely appreciate the past Professors, Dr. Muneyasu Urano, and Mrs. Michiyo Urano, for supporting my work and life. One of the co-authors, Jun Urano, is one of their sons.

References

- Javaux EJ. Challenges in evidencing the earliest traces of life. Nature. 2019;572:451–460. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1436-4

- Joseph R. Climate Change: The First Four Billion Years. The Biological Cosmology of Global Warming and Global Freezing. J Cosmol. 2010;8:2000–2020.

- Stein WD. Transport and diffusion across cell membranes. Academic Press, Devon, UK, 1986. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-664660-3.X5001-7

- Möller MN, Cuevasanta E, Orrico F, Lopez AC, Thomson L, Denicola A. Diffusion and transport of Reactive Species Across Cell Membranes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1127:3–19. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11488-6_1

- Indo HP, Masuda D, Sriburee S, Ito H, Nakanishi I, Matsumoto KI, Mankhetkorn S, Chatatikun M, Surinkaew S, Udomwech L, Kawakami F, Ichikawa T, Matsui H, Tang-pong J, Majima HJ. Evidence of Nrf2/Keap1 Signaling Regulation by Mitochondria-Generated Reactive Oxygen Species in RGK1 Cells. Biomolecules. 2023;13:445. doi:10.3390/biom13030445

- Masuda D, Nakanishi I, Ohkubo K, Ito H, Matsumoto KI, Ichikawa H, Chatatikun M, Klangbud WK, Kotepui M, Imai M, Kawakami F, Kubo M, Matsui H, Tangpong J, Ichikawa T, Ozawa T, Yen HC, St Clair DK, Indo HP, Majima HJ. Mitochondria Play Essential Roles in Intracellular Protection against Oxidative Stress–Which Molecules among the ROS Generated in the Mitochondria Can Escape the Mitochondria and Contribute to Signal Activation in Cytosol? Biomolecules. 2024;14:128. doi:10.3390/biom14010128

- Indo HP, Chatatikun M, Nakanishi I, Matsumoto K, Imai M, Kawakami F, Kubo M, Abe, H, Ichikawa H, Yonei Y, Beppu HJ, Minamiyama Y, Kanekura T, Ichikawa T, Phongphithakchai A, Udomwech L, Sukati S, Charong N, Somsak V, Tangpong J, Nomura S, Majima HJ. The roles of mitochondria in human being’s life and aging. biomolecules. 2024;14:1317. doi:10.3390/biom14101317

- Majima HJ, Oberley TD, Furukawa K, Mattson MP, Yen H-C, Szweda LI, St Clair DK. Prevention of mitochondrial injury by manganese superoxide dismutase reveals a primary mechanism for alkaline-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8217–8224. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.14.8217

- Indo HP, Hawkins CL, Nakanishi I, Matsumoto K, Matsui H, Suenaga S. Davies MJ, St Clair DK, Ozawa T, Majima HJ. Role of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in the activation of cellular signals, molecules, and function. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;240:439–456. doi:10.1007/164_2016_117

- Ito S, Nagata K. Biology of Hsp47 (Serpin H1), a collagen-specific molecular chaperone. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;62:142–151. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.11.005

- Miyamura T, Sakamoto N, Kakugawa T, Taniguchi H, Akiyama Y, Okuno D, Moriyama S, Hara A, Kido T, Ishimoto H, Yamaguchi H, Miyazaki T, Obase Y, Ishimatsu Y, Tanaka Y, Mukae H. Small molecule inhibitor of HSP47 prevents pro-fibrotic mechanisms of fibroblasts in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;530:561–565. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.07.085

- Ramazi S, Zahiri J. Posttranslational modifications in proteins: resources, tools and prediction methods. Database (Oxford). 2021;2021:baab012. doi:10.1093/database/baab012

- Indo, H. P., Ito, H., Nakagawa, K., Chaiswing, L., & Majima, H. J. (2021). Translocation of HSP47 and generation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells following electron and X-ray irradiation. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics, 703, 108853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2021.108853

- Resh MD. Fatty acylation of proteins: The long and the short of it. Prog Lipid Res. 2016;63:120–131. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2016.05.002

- S Mesquita F, Abrami L, Linder ME, Bamji SX, Dickinson BC, van der Goot FG. Mechanisms and functions of protein S-acylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25:488–509. doi:10.1038/s41580-024-00700-8

- Pisanti S, Rimondi E, Pozza E, Melloni E, Zauli E, Bifulco M, Martinelli R, Marcuzzi A. Prenylation defects and oxidative stress trigger the main consequences of neuroinflammation linked to mevalonate pathway deregulation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:9061. doi:10.3390/ijerph19159061

- Wang M, Casey PJ. Protein prenylation: unique fats make their mark on biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:110–122. doi:10.1038/nrm.2015.11

- Jiang H, Zhang X, Chen X, Aramsangtienchai P, Tong Z, Lin, H. Protein lipidation: occurrence, mechanisms, biological functions, and enabling technologies. Chem Rev. 2018;118:919–988. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00750

- Chen B, Sun Y, Niu J, Jarugumilli GK, Wu X. Protein lipidation in cell signaling and diseases: function, regulation, and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Chem Biol. 2018;25:817–831. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.05.003

- Yuan Y, Li P, Li J, Zhao Q, Chang Y, He X. Protein lipidation in health and disease: molecular basis, physiological function and pathological implication. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:60. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01759-7

- Wang R, Chen YQ. Protein lipidation types: current strategies for enrichment and characterization. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:2365. doi:10.3390/ijms23042365

- Palsuledesai CC, Distefano MD. Protein prenylation: enzymes, therapeutics, and biotechnology applications. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:51–62. doi:10.1021/cb500791f

- Swahari V, Nakamura A. Speeding up the clock: The past, present and future of progeria. Dev Growth Differ. 2016;58:116–130. doi:10.1111/dgd.12251

- Capell BC, Erdos MR, Madigan JP, Fiordalisi JJ, Varga R, Conneely KN, Gordon LB, Der CJ, Cox AD, Collins FS. Inhibiting farnesylation of progerin prevents the characteristic nuclear blebbing of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12879–12884. doi:10.1073/pnas.0506001102

- Fong LG, Frost D, Meta M, Qiao X, Yang SH, Coffinier C, Young SG. A protein farnesyltransferase inhibitor ameliorates disease in a mouse model of progeria. Science. 2006;311:1621–1623. doi:10.1126/science.1124875

- Yang SH, Chang SY, Ren S, Wang Y, Andres DA, Spielmann HP, Fong LG, Young SG. Absence of progeria-like disease phenotypes in knock-in mice expressing a non-farnesylated version of progerin. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:436–444. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq490

- Capell BC, Erdos MR, Madigan JP, Fiordalisi JJ. Varga R, Conneely KN. Gordon LB, Der CJ, Cox AD, Collins FS. Inhibiting farnesylation of progerin prevents the characteristic nuclear blebbing of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12879–12884. doi:10.1073/pnas.0506001102

- Zhang FL, Casey PJ. Protein prenylation: molecular mechanisms and functional consequences. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:241–269. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001325,

- Yuan M, Song ZH, Ying MD, Zhu H, He QJ, Yang B, Cao J.. N-myristoylation: from cell biology to translational medicine. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41:1005–1015. doi:10.1038/s41401-020-0388-4

- Gelb MH, Brunsveld L, Hrycyna CA, Michaelis S, Tamanoi F, Van Voorhis WC, Waldmann H. Therapeutic intervention based on protein prenylation and associated modifications. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:518–528. doi:10.1038/nchembio818

- Tsuchiya E, Fukui, S, Kamiya Y, Sakagami Y, Fujino M. Requirements of chemical structure for hormonal activity of lipo-peptidyl factors inducing sexual differentiation in vegetative cells of heterobasidiomycetous yeasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978;85:459–463. [PubMed:743289]

- Sakagami Y, Isogai A, Suzuki A, Tamura S, Tsuchiya E, Fukui S. Isolation of a novel sex hormone, tremerogen A-10, controlling conjugation tube formation in Tremella mesenterica fries. Agric Biol Chem. 1978;42:1093–1094. doi:10.1080/00021369.1978.10863118

- Sakagami Y, Yoshida M, Isogai A, Suzuki A. Peptidal sex hormones inducing conjugation tube formation in compatible mating-type cells of Tremella mesenterica. Science. 1981;212:1525–1527. doi:10.1126/science.212.4502.1525

- Kamiya Y, Sakurai A, Tamura S, Takahashi N. Structure of rhodotorucine A, a novel lipopeptide, inducing mating tube formation in Rhodosporidium toruloides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978;83:1077–1083. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(78)91505-x

- Ishibashi Y, Sakagami Y, Isogai A, Suzuki,A. Structures of tremerogens A-9291-I and A-9291-VIII: peptidal sex hormones of Tremella brasiliensis. Biochemistry. 1984;23:1399–1404. doi:10.1021/BI00302A010

- Casey PJ. Mechanisms of protein prenylation and role in G protein function. Biochem Soc Trans. 1995;23:161–166. doi:10.1042/bst0230161

- Del Villar K, Dorin D, Sattler I, Urano J, Poullet P.; Robinson N, Mitsuzawa H, Tamanoi F. C-terminal motifs found in Ras-superfamily G-proteins: CAAX and C-seven motifs. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:709–713. doi:10.1042/bst0240709

- Marshall CJ. Protein prenylation: a mediator of protein-protein interactions. Science. 1993;259:1865–1866. doi:10.1126/science.8456312

- Vandermoten S, Haubruge É, Cusson M. New insights into short-chain prenyltransferases: structural features, evolutionary history and potential for selective inhibition. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3685–3695. doi:10.1007/s00018-009-0100-9

- Boutin JA. Myristoylation. Cell Signal. 1997;9:15–35. doi:10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00100-3

- Ochoa-Solano A, Romero G, Gitler C. Catalysis of ester hydrolysis by mixed micelles containing N-alpha-myristoyl-L-histidine. Science. 1967;156:1243–1244. doi:10.1126/science.156.3779.1243

- Boveris A, Navarro A. Brain mitochondrial dysfunction in aging. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:308–314. doi:10.1002/iub.46

- Baker ZN, Forny P, Pagliarini DJ. Mitochondrial proteome research: the road ahead. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25:65–82. doi:10.1038/s41580-023-00650-7

- Wiedemann N, Pfanner N. Mitochondrial machineries for Protein and assembly. Annu Rev Biochem. 2017;86:685–714. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014352

- DiMauro S, Schon EA. Mitochondrial disorders in the nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:91–123. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094302

- Pfanner N, Warscheid, B, Wiedemann N. Mitochondrial proteins: from biogenesis to functional networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:267–284. doi:10.1038/s41580-018-0092-0

- Böttinger L, Ellenrieder L, Becker T. How lipids modulate mitochondrial protein import. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2016;48:125–135. doi:10.1007/s10863-015-9599-7

- Gebert N, Ryan MT, Pfanner, N, Wiedemann N, Stojanovski D. Mitochondrial protein import machineries and lipids: functional connection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808:1002–1011. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.08.003

- Lübben M, Morand K. Novel prenylated hemes as cofactors of cytochrome oxidases. Archae have modified hemes A and O. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21473–21479. PMID:8063781

- Frohlich M, Dejanovic B, Kashkar H, Schwarz G, Nussberger S. S-palmitoylation represents a novel mechanism regulating the mitochondrial targeting of BAX and initiating apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1057. doi:10.1038/cddis.2014.17

- Liang J, Xu ZX, Ding Z, Lu Y, Yu Q, Werle KD, ZhouG, Park YY, Peng G, Gambello MJ, Mills GB. Myristoylation confers noncanonical AMPK functions in autophagy selectivity and mitochondrial surveillance. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7926. doi:10.1038/ncomms8926

- Kostiuk MA, Corvi MM, Keller BO, Plummer G, Prescher JA, Hangauer MJ, Bertozzi CR, Rajaiah G, Falck JR, Berthiaume LG. Identification of palmitoylated mitochondrial proteins using a bio-orthogonal azido-palmitate analog. FASEB J. 2008;22:721–732. doi:10.1096/fj.07-9199com

- Blanco-Colio LM, Justo P, Daehn I, Lorz C, Ortiz A, Egido J. Bcl-xL overexpression protects from apoptosis induced by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in murine tubular cells. Kidney Int. 2003;64:181–191. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00080.x

- Zha J, Weiler, S, Oh KJ, Wei MC, Korsmeyer SJ. Posttranslational N-myristoylation of BID as a molecular switch for targeting mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 2000;290: 1761–1765. doi:10.1126/science.290.5497.1761

- Utsumi T, Sakurai N, Nakano K, Ishisaka R. C-terminal 15 kDa fragment of cytoskeletal actin is posttranslationally N-myristoylated upon caspase-mediated cleavage and targeted to mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2003;539:37–44. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00180-7

- Bivona TG, Quatela SE, Bodemann BO, Ahearn IM, Soskis MJ, Mor A, Miura J, Wiener HH, Wright L, Saba SG, Yim D, Fein A, Pérez de Castro I, Li C, Thompson CB, Cox AD, Philips MR. PKC regulates a farnesyl-electrostatic switch on K-Ras that promotes its association with Bcl-XL on mitochondria and induces apoptosis. Mol. 2006;21:481-493. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.012

- Beauchamp E, Tekpli X, Marteil, G, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Legrand P, Rioux V. N-myristoylation targets dihydroceramide Delta4-desaturase 1 to mitochondria: partial involvement in the apoptotic effect of myristic acid. Biochimie. 2009;91:1411–1419. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2009.07.014

- Lynes EM, Raturi A, Shenkman M, Ortiz Sandoval C, Yap MC, Wu J, Janowicz A, Myhill N, Benson MD, Campbell RE, Berthiaume LG, Lederkremer GZ, Simmen T. Palmitoylation is the switch that assigns calnexin to quality control or ER Ca2+ signaling. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:3893–3903. doi:10.1242/jcs.125856

- Bhat SA, Vasi Z, Jiang L, Selvaraj S, Ferguson R, Salarvand S, Gudur A, Adhikari R, Castillo V, Ismail H, Dhabaria A, Ueberheide B, Kuchay S. Geranylgeranylated-SCFFBXO10 regulates selective outer mitochondrial membrane proteostasis and function. Cell Rep. 2024;43:114783. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114783

- Ducluzeau AL, Wamboldt Y, Elowsky CG, Mackenzie SA, Schuurink RC, Basset GJ. Gene network reconstruction identifies the authentic trans-prenyl diphosphate synthase that makes the solanesyl moiety of ubiquinone-9 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2012;69:366–375. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04796.x

- Grant J, Saldanha JW, Gould AP. A Drosophila model for primary coenzyme Q deficiency and dietary rescue in the developing nervous system. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:799–806. doi:10.1242/dmm.005579

- Artuch R, Brea-Calvo G, Briones P, Aracil A, Galván M, Espinós C, Corral J, Volpini V, Ribes A, Andreu AL, Palau F, Sánchez-Alcázar JA, Navas P, Pineda M. Cerebellar ataxia with coenzyme Q10 deficiency: diagnosis and follow-up after coenzyme Q10 supplementation. J Neurol Sci. 2006;246:153–158. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2006.01.021

- Saiki R, Lunceford, A.L, Shi Y, Marbois B, King R, Pachuski J, Kawamukai M, Gasser DL, Clarke CF. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation rescues renal disease in Pdss2kd/kd mice with mutations in prenyl diphosphate synthase subunit 2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1535–F1544. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.90445.2008

- Marakasova, E.S.; Eisenhaber, B.; Maurer-Stroh, S.; Eisenhaber, F.; Baranova, A. Prenylation of viral proteins by enzymes of the host: Virus-driven rationale for therapy with statins and FT/GGT1 inhibitors. Bioessay. 2017;39:10. doi:10.1002/bies.201700014

- Einav S, Glenn JS. Prenylation inhibitors: a novel class of antiviral agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:883–886. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg490

- Glenn JS, Watson JA, Havel CM, White JM. Identification of a prenylation site in delta virus large antigen. Science. 1992;256:1331–1333. doi:10.1126/science.1598578

- Bordier BB, Marion PL, Ohashi K, Kay MA, Greenberg HB, Casey JL, Glenn JS. A prenylation inhibitor prevents production of infectious hepatitis delta virus particles. J Virol. 2002;76:10465–10472. doi:10.1128/jvi.76.20.10465-10472.2002

- V’kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:155–170. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6

- Zhou Y, Liu Y, Gupta S, Paramo MI, Hou Y, Mao C, Luo Y, Judd J, Wierbowski S, Bertolotti M, Nerkar M, Jehi L, Drayman N, Nicolaescu, V, Gula H, Tay S, Randall G, Wang P, Lis JT, Feschotte C, Erzurum SC, Cheng F, Yu H. A comprehensive SARS-CoV-2-human protein-protein interactome reveals COVID-19 pathobiology and potential host therapeutic targets. Nat Biotechnol. 2023;41:128–139. doi:10.1038/s41587-022-01474-0