Physiological Interpretation of CTG: Intrapartum FIT-CAT

Physiological Interpretation of Cardiotocograph (CTG): The role of the intrapartum “FIT-CAT”

ABSTRACT

Intrapartum fetal well-being depends on good placental function for gaseous exchange as well as transfer of nutrients and removal of fetal metabolic waste products. Optimal intrauterine fetal environment with clear and copious amniotic fluid without any microbial invasion as well as a conducive maternal environment that facilitates fetal growth and wellbeing are equally important. This is because in addition to normal maternal oxygen saturation and normal functioning of the maternal liver, kidneys, lungs, cardiac function with sufficient perfusion pressure to the placenta, the fetus also depends on appropriate “concentrations,” gradients of maternal byproducts and body heat generated during growth, which are essential for normal fetal development. If there is a delay in recognizing these features suggestive of fetal compromise, fetal neurological injury or a terminal myocardial failure may occur. For example, a fetus with the background history of spontaneous prelabour rupture of membranes (SROM) may display a “normal” CTG at the onset of labour and therefore, this fetus will be misdiagnosed if CTG changes are not interpreted correctly. Robust Intrapartum Fetal Surveillance (RIFS) does not solely depend on the use and the correct interpretation of the cardiotocograph. It involves a careful scrutiny of the clinical context, which includes both antepartum and intrapartum risk factors. In addition, the anticipated and predicted CTG changes based on the observed clinical context are crucial in the interpretation of the cardiotocograph. This review aims to highlight the importance of the intrapartum “FIT-CAT” and how it can be utilized to optimize perinatal outcomes.

Keywords

- Cardiotocograph

- Intrapartum

- Fetal well-being

- FIT-CAT

- Perinatal outcomes

Introduction

Intrapartum fetal well-being depends on good placental function for gaseous exchange as well as transfer of nutrients and removal of fetal metabolic waste products. Optimal intrauterine fetal environment with clear and copious amniotic fluid without any microbial invasion as well as a conducive maternal environment that facilitates fetal growth and wellbeing are equally important. This is because in addition to normal maternal oxygen saturation and normal functioning of the maternal liver, kidneys, lungs, cardiac function with sufficient perfusion pressure to the placenta, the fetus also depends on appropriate “concentrations,” gradients of maternal byproducts and body heat generated during growth, which are essential for normal fetal development. If there is a delay in recognizing these features suggestive of fetal compromise, fetal neurological injury or a terminal myocardial failure may occur. For example, a fetus with the background history of spontaneous prelabour rupture of membranes (SROM) may display a “normal” CTG at the onset of labour and therefore, this fetus will be misdiagnosed if CTG changes are not interpreted correctly.

Robust Intrapartum Fetal Surveillance (RIFS) does not solely depend on the use and the correct interpretation of the cardiotocograph. It involves a careful scrutiny of the clinical context, which includes both antepartum and intrapartum risk factors. In addition, the anticipated and predicted CTG changes based on the observed clinical context are crucial in the interpretation of the cardiotocograph. This review aims to highlight the importance of the intrapartum “FIT-CAT” and how it can be utilized to optimize perinatal outcomes.

Table 1: FIT for Labour-Clinical Anticipation Tool (FIT-CAT)

| Risk Factor | Impact on the Fetal pathophysiology | Expected CTG changes and likely underlying mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal Growth Restriction | Oligohydramnios | Tardy decelerations and increased baseline with the onset of uterine contractions. |

| Renal/uteroplacental insufficiency of labour (RUPL) | Late onset and second stage of labour. | Absence of accelerations. |

| Polyhydramnios | Macrosomia | Increased baseline FHR variability. |

However, even the fetuses which are deemed normal or do not exhibit intrapartum risk factors may increase the likelihood of fetal compromise. If there is a delay in recognizing these features suggestive of fetal compromise, fetal neurological injury or a terminal myocardial failure may occur. For example, a fetus with the background history of spontaneous prelabour rupture of membranes (SROM) may display a “normal” CTG at the onset of labour and therefore, this fetus will be misdiagnosed if CTG changes are not interpreted correctly.

Robust Intrapartum Fetal Surveillance (RIFS) does not solely depend on the use and the correct interpretation of the cardiotocograph. It involves a careful scrutiny of the clinical context, which includes both antepartum and intrapartum risk factors. In addition, the anticipated and predicted CTG changes based on the observed clinical context are crucial in the interpretation of the cardiotocograph.

Table 2: Expected CTG changes and likely underlying mechanisms

| Risk Factor | Impact on the Fetal pathophysiology | Expected CTG changes and likely underlying mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Occipito-posterior position (OP) | A sudden and sustained drop in the baseline FHR in late first stage or early second stage as the deflected fetal head compresses the airway anterior fontanelle which has nerve supply from parasympathetic nerves. | In the absence of hypoxic stress, the baseline FHR variability remains normal. |

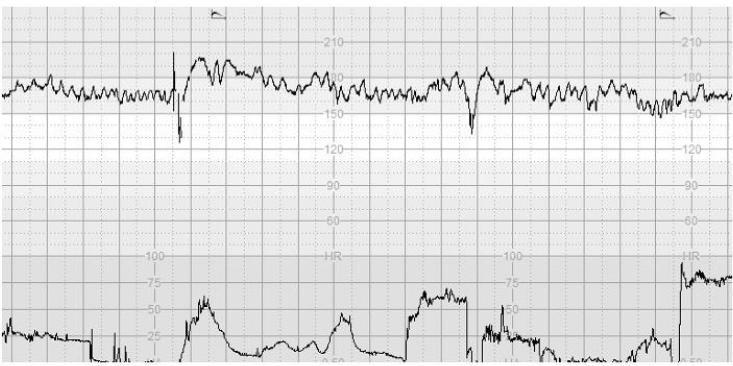

| Commencement active labour | Subacute hypoxic pattern or ZigZag pattern. | Subtle hypoxic pattern detected immediately after labour commences. |

| Forceps Birth | Increased risk of uterine rupture. | Increased baseline FHR variability. |

It is indeed important to appreciate that the fetus depends on the concentration gradient for the transfer of essential nutrients from the mother and metabolic byproducts to the mother via the placenta. Therefore, in maternal pyrexia and metabolic acidosis, this concentration gradient would be affected, resulting in alteration of heat and metabolic acids and other waste products within the fetal compartment.

Table 3: Clinical Rationale of the Chorio-Duck Score (CDS)

| Parameter | Clinical Relevance | Why does this change occur? |

|---|---|---|

| Increase in the Baseline FHR | An increased demand of oxygen in the presence of infection in a fetus in the baseline heart rate. This helps to maintain aerobic metabolism by increasing oxygen delivery to tissues and organs to prevent metabolic acidosis. | However, the use of the intrapartum FIT-CAT may help frontline clinicians to avoid superimposed hypoxic injury. |

It is imperative that some CTG guidelines emphasize the importance of the intrapartum clinical context. This is particularly important as the clinical context can result in the misdiagnosis of the fetus as being “normal, suspicious and pathological,” focusing on the morphology of deviations in FHR due to the presence of increased myocardial workload and augmented cardiac oxygen demand.

Table 4: Impact of persistent adverse maternal environment with super-imposed intrapartum hypoxic stress

| Observed Abnormality | Expected metabolic rate and its impact | Likely outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent fever | Increased metabolic rate due to reduced oxygenation/denaturation of proteins. | Fetal hypoxic failure. |

| Persistent tachycardia | Increased demand for oxygen delivery to myocytes. | Fetal hypoxic failure. |

Conversely, it must be appreciated that some medications may blunt the anticipated fetal heart rate changes, leading to disastrous consequences. For example, nonspecific beta-blockers such as propranolol and labetalol may blunt the fetal catecholamine response and therefore, the baseline FHR variability would be markedly reduced. For example, nonspecific beta-blockers such as propranolol and labetalol may blunt the fetal catecholamine response and therefore, the baseline FHR variability would be markedly reduced.

Table 5: Treatment-Interventions (effects on the fetal pathophysiology)

| Treatment/Intervention | Mechanism of Action (effects on the fetal system) | Expected CTG changes |

|---|---|---|

| Atropine | Stimulation of the myocardiopathy by increasing the heart rate. | Increase in the baseline FHR. |

| Labetalol | Blocks β1 receptors. | Decrease in the baseline FHR variability. |

Several publications have recommended that the use of the intrapartum CTG should be based on the clinical context, which is essential to avoid unnecessary interventions and their undesirable consequences.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is hoped that the use of the FIT-CAT will aid frontline clinicians to predict the expected changes based on the observed clinical context. It is imperative that the clinical context should be considered and delivered parameters included in the clinical decision-making process.

Conflict of Interest

EC conceived the concept of “FIT-CAT.” SG, YK, ME and MB contributed to the drafting of the manuscript, reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Funding Statement

None.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- Chandharan, E., Tahan, M.E., Pereira, S. (2019). Intrapartum care: An urgent need to question historical practices and non-evidence-based, illogical fetal monitoring guidelines to avoid perinatal harm. Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management 24(5): 210-217.

- Pereira, S., Chandharan, E. (2020). Reproductive hypoxia and pre-existing fetal injury in labour. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(3):315-9.

- Sukumaran, S., Teo, J.Y., Chandharan, E. (2021). Uterine Tachysystole, Hypertonus and Hyperstimulation: An urgent need to get the definitions right to avoid Intrapartum Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury. Glob J Reprod Med. 2021; 8(2): 55-63.