Post-Approval Change Management for Virus Filters

Post-Approval Change Management for Virus Retentive Filters

Albrecht Groner

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED 31 August 2025

CITATION Groner, A., 2025. Post-Approval Change Management for Virus Retentive Filters. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6800

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6800

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Virus clearance steps inactivation and/or removal of viruses have to be implemented in the manufacturing process of biologicals to assure a high margin of virus safety of these products for patients in need. The implementation of virus retentive filters result in a robust virus clearance as only the size/shape of viruses is relevant in the context of the removal capacity of the filters viruses larger than the mean pore size of a virus retentive filter are removed from the feed stream and the desired protein and not the properties of viruses as enveloped or non-enveloped, single or double stranded DNA or RNA, and resistance to physicochemical treatment. When during the lifecycle of the product a change of the established virus retentive filter is required due to e.g., supply issues by the manufacturer of these filters currently implemented in the manufacturing process or an improved filter is provided by filter manufacturers, a change of filters has to or may be initiated. This post-approval change has to meet regulatory guidance, e.g., ICH (International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use) guidelines, for licensed products. When changing virus retentive filters, the critical parameters volumetric throughput of product intermediate and, when performed, buffer flush, pressure, pressure/flow interruption, and flow decay have to be validated for the new filter demonstrating the same or improved virus clearance capacity. Comparable drug substance properties regarding, besides virus removal capacity, e.g., impurities and protein aggregates, have to be demonstrated. Validation data comparing the current with the changed process, based on prior knowledge of established engineering principles and applied manufacturing experience, especially during the development of the drug substance, published literature and other information form the basis of the risk assessment prior to implement the change. After having assessed the impact of the change in virus retentive filters according to regulatory guidelines without negative effects on product quality and safety, the potential change has to be reported to the relevant regulatory authority in line with existing regional regulations and guidance.

Keywords

Virus retentive filters, post-approval change management, virus clearance, regulatory guidelines, pharmaceutical manufacturing

2. Introduction

Commercially available virus retentive filters are first launched in 1989 by Asahi Kasei; this filter (Planova 35N) had a mean pore size of 35 ± 2 nm removing midsized and large viruses, a so-called large virus retentive filter. The small virus filter, Planova 15N, with mean pore sizes of 15 ± 2 nm removing small viruses, followed. Meanwhile, further virus retentive filters by different suppliers are on the market with different membrane composition and structures (Table 1).

The integration of virus retentive filters, especially small virus filters, in the manufacturing process of plasma- and cell culture-derived biologicals increases the virus safety of these products considerably resulting in a high margin of virus safety. As commonly the lifecycle of a biological exceeds the cycle of equipment as virus retentive filters, a change control process has to be initiated. Such a process has to be implemented not only when the supplier of such filters stops the production of a specific filter type currently used but also when new filters with improved properties are developed by a supplier of virus retentive filters as increased filtration capacity, especially for complex proteins, with minimal impact on flow decay / flow interruption, avoidance of premature fouling and improved virus reduction capacity for small viruses.

The change of small virus retentive filters for a marketed product, a so-called post-approval change, will be addressed in this paper based on regulatory guidance. Chemistry, Manufacturing and Controls (CMC) changes across the product lifecycle vary from low to high potential risk with respect to product quality, safety, and efficacy, including identity, strength, quality, purity, and potency. Therefore, a risk assessment of the impact of the change on product quality and the strategy how potential risks will be mitigated or managed has to be performed.

According to the ICH Q12 guideline, CMC changes occurring during the commercial phase of the product lifecycle should be communicated with regulatory authorities according to a process established by the MAH (marketing authorisation holder) / company comprehending the potential of having an adverse effect on product quality; also regulatory authorities are encouraged to utilise a system that incorporates risk-based regulatory processes. Based on this risk assessment, a prior approval from regulatory authorities, a notification of the regulatory authorities, or simply recording CMC changes is requested. The concepts for science- and risk-based approaches for use in drug development and regulatory decisions are outlined in the ICH Quality Guidelines ICH Q8 (R2), Q9(R1), Q10, and Q11. These guidelines are valuable in the assessment of CMC changes across the product lifecycle. ICH Q8(R2) and Q11 guidelines focus mostly on early-stage aspects of the product lifecycle (i.e., product development, registration and launch). The ICH Q12 guideline on lifecycle management addresses the commercial phase of the product lifecycle and complements and adds to the flexible regulatory approaches to post-approval CMC changes described in ICH Q8(R2) and Annex 1 Q10. A prerequisite of the change management is the adequate implementation of the regulatory framework in place, as well as product and process understanding (ICH Q8(R2) and Q11), application of quality risk management principles (ICH Q9), and an effective pharmaceutical quality system (ICH Q10).

Table 1: Relevant virus retentive filters covered in publications assessed

| Manufacturer | Brand | Membrane Chemistry / Format | Mean Pore Size* | Max. Operating pressure [bar] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asahi Kasei | Planova 15N | hydrophilic cuprammonium regenerated cellulose / hollow fibre | 15 ± 2 | 0.98 |

| Planova 20N | Small virus retentive filter | 19 ± 2 | 0.98 | |

| Planova S20N | Small virus retentive filter | 2.16 | ||

| Planova 35N | Large virus retentive filter | 35 ± 2 | 0.98 | |

| Planova BioEX | hydrophilic PVDF / hollow fibre | 3.43 | ||

| Planova FG1 | hydrophilic PES / hollow fibre | 3.43 | ||

| Cobetter | Viruclear VF(PES) Plus | hydrophilic PES / membrane | Not disclosed | |

| Viruclear RC H | regenerated cellulose / membrane | Not disclosed | ||

| Merck Millipore | Viresolve Pro | hydrophilic PES / membrane | 3.5 / 4.1 | |

| Viresolve NFR | hydrophilic PES / membrane | 5.5 | ||

| Viresolve NFP | hydrophilic PVDF / membrane | 5.5 | ||

| Cytiva | Ultipor DV50 | hydrophilic PVDF / membrane | 3.0 | |

| Ultipor DV20 | hydrophilic PVDF / membrane | 3.1 | ||

| Pegasus SV4 | hydrophilic PVDF / membrane | 3.1 | ||

| Sartorius | Virosart CPV | hydrophilic PES / membrane | 5.0 | |

| Virosart HC | hydrophilic PES / membrane | 5.0 | ||

| Virosart HF | hydrophilic PES / membrane | 5.0 |

3. General Aspects of Change Control Management

A (post-approval) change may potentially impact product quality as the safety or efficacy of the product; therefore, such a proposed change has to be thoroughly assessed and documented. Knowledge and experience accumulated during development and commercial manufacturing of the product regarding product performance relating to process parameters provide information and data to demonstrate comparability of the product pre- and post-change. A main aspect of accepting post-approval changes is virtually identical product quality, demonstrated by risk assessments based on prior knowledge and validation data.

As stated in ICH Q12 guideline, increased product and process knowledge contribute to a more precise and accurate understanding of which post-approval changes require a regulatory submission as well as the definition of the level of reporting categories for such changes; moderate to low risk regarding product quality after change require commonly a notification to the respective regulatory authority (before or after the implementation of the change according to regional requirements) vs. a prior approval for a high risk change. Increased knowledge and effective implementation of the tools and enablers described in this ICH Q12 guideline should enhance industry’s ability to manage many CMC changes effectively under the company’s Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS) with less need for extensive regulatory oversight prior to implementation. The guideline outlines the following regulatory tools and enablers (i) categorisation of the intended post-approval CMC changes to enable the implementation of certain CMC changes for authorised products without the need for prior regulatory review and approval depending on the risk to product quality related to the change, (ii) Established Conditions, i.e., information provided in the Common Technical Document (CTD) submitted for licensure of a specific product to assure product quality, based on pharmaceutical development activities resulting in an appropriate control strategy, (iii) Post-Approval Change Management Protocol (PACMP) providing predictability regarding planning for future changes to ECs, (iv) Product Lifecycle Management (PLMC) document, a summary that transparently conveys to the regulatory authority how the Marketing Authorisation Holder (MAH) plans to manage post-approval CMC changes, (v) Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS) and Change Management, managing all CMC changes to an approved product including the reporting of changes to ECs to regulatory authorities, (vi) Structured Approaches for Frequent CMC Post-Approval Changes to enable the implementation of certain, i.e., moderate to low risk CMC changes for authorised products without the need for prior regulatory review and approval, and (vii) Stability Data Approaches to Support the Evaluation of CMC Changes, i.e., stability studies, if needed, are to confirm the previously approved shelf-life and storage conditions to support a post-approval CMC change depending on the stability-related quality attributes and shelf-life-limiting attributes relative to the intended CMC changes, based on risk assessments and previously generated data.

ICH Q7 describes Change Control activities in the context of GMP and Quality System elements, i.e., a formal change control system should be established, evaluating all changes potentially impacting quality and safety of intermediates or drug product. Written procedures should provide for the identification, documentation, appropriate review, and approval of changes in raw materials, specifications, analytical methods, facilities, support systems, equipment (including computer hardware), processing steps, labelling and packaging materials, and computer software and planned changes should be reviewed and approved by the quality assurance unit(s). Changes can be classified (e.g. as minor or major) depending on the nature and extent of the changes, and the effects these changes may impart on the process. Scientific judgement should determine what additional testing and validation studies are appropriate to justify a change in a validated process. This approach results in a Change Management as described in ICH Q10.

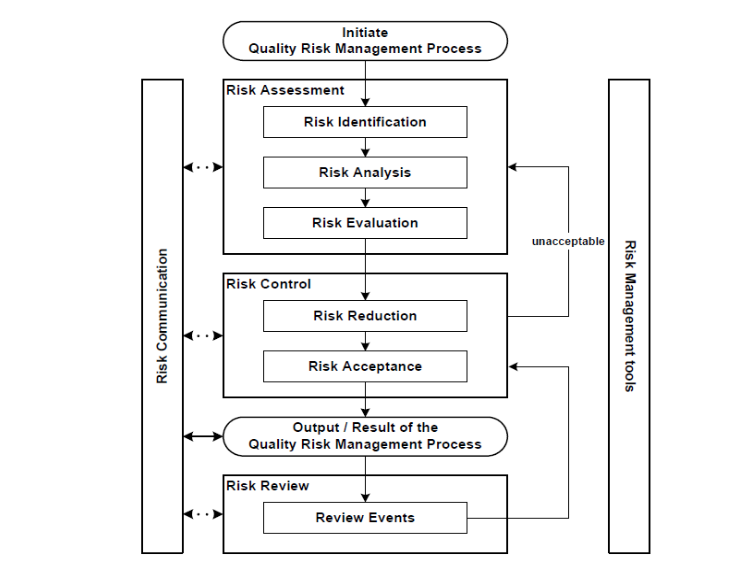

The implementation of a Pharmaceutical Quality System, e.g., a model according to ICH Q10, could facilitate the interaction between development (including, if applicable, technology transfer), commercial manufacturing, and product discontinuation, based on International Standards Organisation (ISO) quality concepts and applicable GMP regulations complementing ICH Q8 and ICH Q9. The quality risk management process, a part of the pharmaceutical quality system, should be applied in order to evaluate the impact of the replacement of the previously/currently used filter by another filter on the quality, safety and efficacy of biotechnological/biological products. This quality risk management allows science-based decision making with respect to risk and the risk assessment may answer three fundamental questions: (i) what might go wrong, (ii) what is the probability it will go wrong, and (iii) what is the severity if something goes wrong?

The risk assessment includes risk identification, risk analysis, and risk evaluation. The output of the risk assessment is often expressed qualitatively, i.e., high, medium, or low risk. The following risk control includes decision making to reduce and/or accept risks (when the risk is at an acceptable level). Mitigation or avoidance of quality risk has to be initiated when it exceeds a specified (acceptable) level. Risk acceptance could be a formal decision to accept a residual risk.

The result of the quality risk management process should be communicated with the regulatory agencies. The risk review is an ongoing part of the quality management process over the lifecycle of the product in order to modify the original quality risk management decision, if required, based on increased knowledge and planned and unplanned events (e.g., inspections, audits, and root cause from failure investigations, recalls).

4. Change Control Management for Virus Retentive Filters

4.1 QUALITY MANAGEMENT PROCESS ACCORDING TO ICH Q9

4.1.1 Risk Assessment

A quality risk management process according to ICH Q9 evaluates the risk to quality based on scientific knowledge and ultimately link to the protection of the patient. In addition, the level of effort, formality and documentation of the quality risk management process should be commensurate with the level of risk. A risk assessment could be performed in line with a FMEA (Failure Mode Effects Analysis) approach covering the aspects failure, factors causing this failure and the likely effects (severity) of these failures. As in the context of replacing virus retentive filters by other filters failures are not the primary focus of the analysis but assuring/maintaining product identity, strength, quality, and purity as these factors relate to the product’s quality, safety, and efficacy a proactive approach according to the HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) proposition is considered more appropriate than the FMEA approach.

4.1.1.1 Risk Identification

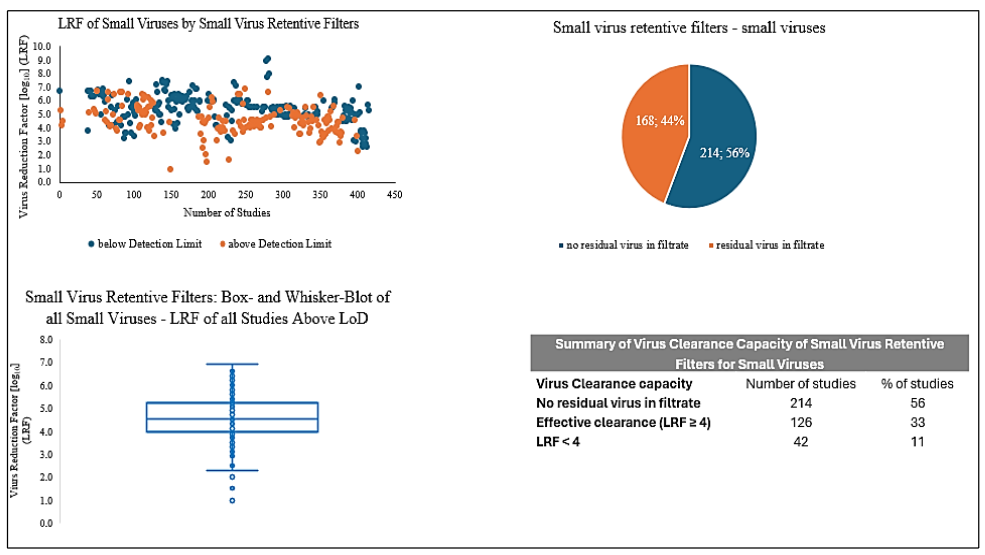

As, in principle, each change in equipment may have an impact on the quality, safety and efficacy of drug products, the replacement of virus retentive filters has to be assessed. The rational for implementation of virus retentive filters in the manufacturing process of biologicals is the removal of endogenous and adventitious viruses, i.e., viruses (potentially) present in the starting material, i.e., unprocessed bulk/bioreactor harvest of cell culture-derived products and plasma pools for fractionation of plasma-derived medicinal products (PDMPs). A potential risk is the need for a robust, effective removal of small viruses under all process related conditions. Furthermore, virus retentive filters including pre-filters when used may polish the drug substance by removing large accompanying proteins (larger than the mean pore size of the filters) changing the physicochemical properties of the product to a certain degree or may even activate enzymes, e.g., due to shear stress. In addition, a potential impact of filter components on the physicochemical and biological properties of the drug substance / product has to be assessed. Lute et al. reported that the passage of the phage PP7 and ΦX-174 into the filtrate of small virus retentive filters (Viresolve NFP, Virosart CPV, Ultipor DV20, and Planova 20N) occurred in each filter type, particularly when overloaded with phage. The authors also reported brand-specific differences in flux decay due to phage overload and concluded that small virus retentive filters should not be viewed as absolute in their capacity to clear virus and they should not be viewed as interchangeable between brands; therefore, a change control approach has to be initiated when virus retentive filters are replaced by other (small) virus retentive filters. It is also reported that data assessing the so-called second-generation of small virus retentive filters (Planova BioEX, Viresolve Pro) showed that these improved filters were able to remove e.g., parvoviruses to a higher degree as the so-called first-generation of small virus retentive filters (Planova 15N, Planova 20N, Viresolve NFP, Virosart CPV, Ultipor DV20) and appeared to have less variability in the reported LRFs (virus reduction factor in log10). This improved virus clearance capacity of so-called second-generation small virus retentive filters for parvoviruses is confirmed documenting effective removal (LRF 4) in 97% of studies vs. 85% for first-generation small virus retentive filters. Furthermore, transmembrane pressure and volumetric throughput had an impact on LRFs in first-generation small virus retentive filters in contrast to second-generation small virus retentive filters.

Based on this information, a post-approval change of virus retentive filters with improved properties may be appropriate to enhance the overall virus safety of a product. In a further publication covering data for virus removal by different small virus retentive filters (Planova 15N, ~20N, ~BioEX, Viresolve NFP, Ultipore DV20, Pegasus SV4, Virosart CPV, ~HC) a considerable range of LRFs for the different small virus filters are shown.

Recalculation of these data for all small viruses considering also so-called first-and second-generation of small virus retentive filters (Planova 15N, ~ 20N, Viresolve 70, ~ NFP, and Virosart CPV vs. Planova BioEX, Viresolve Pro, Pegasus SV4, and Virosart HC) resulted in a considerable higher virus clearance capacity of the so-called second-generation small virus retentive filters: The median LRF for so-called first-generation small virus retentive filters was 4.4 with lower/upper quartile of 3.9/5.0 vs. a median of 5.5 with lower/upper quartile of 4.8/6.5 for so-called second-generation filters. The data for parvoviruses presented as figure in Ajayi et al. were calculated: for first-generation small virus retentive filters a median of 5.1 LRF and lower/upper quartile of 4.0/6.3 LRFs versus second-generation small virus retentive filters with a median of 5.8 LRF and lower/upper quartile of 5.4/6.2 LRFs could be demonstrated, documenting also in this publication a considerable improved virus removal capacity of the newer virus retentive filters. An improved reduction capacity for small viruses would also be desirable based on published data for plasma-derived medicinal products as in approx. 70% of studies parvoviruses could be detected in the filtrate of small virus retentive filters. In submissions of data to the FDA for small virus retentive filters and parvoviruses, the LRFs varied from approx. 1 to 8; also this large range should be reduced considerably and filters achieving an effective virus removal capacity, i.e., LRF of 4, should be implemented in the manufacturing process of biologicals.

4.1.1.2 Risk Analysis

Virus retention is due to filtration of the feed stream through membranes or hollow fibres of defined pore sizes prepared from different materials. As stated above, different (small) virus retentive filters have different capacities to remove small viruses. As stated in the ICH Q5A(R2) guideline, the following process parameters or factors have a high potential effect on the clearance of small viruses as parvoviruses: (i) volumetric throughput of product intermediate loaded on the virus filter, also (ii) the volumetric throughput of the buffer used for flushing filters (to improve the yield of the drug substance), and (iii) the pressure applied and flow (low pressure/flow can be worse case for specific filter types, i.e., flow decay due to blockage of a filter has to be restricted to a predetermined specification). Furthermore, the impact of flow interruption, e.g., when switching from product intermediate to buffer for filter flush has to be assessed in virus clearance studies. The impact of these process parameters on the virus clearance capacity of the new, to be implemented, virus retentive filter has to be assessed in virus clearance studies employing the relevant, product-specific intermediate. A potential shear stress on the desired drug substance, especially when changing filter with a low to a considerably higher maximum transmembrane pressure and flow rate, could theoretically result in an alteration of its physicochemical and biological properties and, thus, impacting the quality, safety, and efficacy of the drug product. Test methods established during the development of the product, especially for the filtration process, should be used to exclude such modifications of the drug substance/product.

4.1.1.3 Risk Evaluation

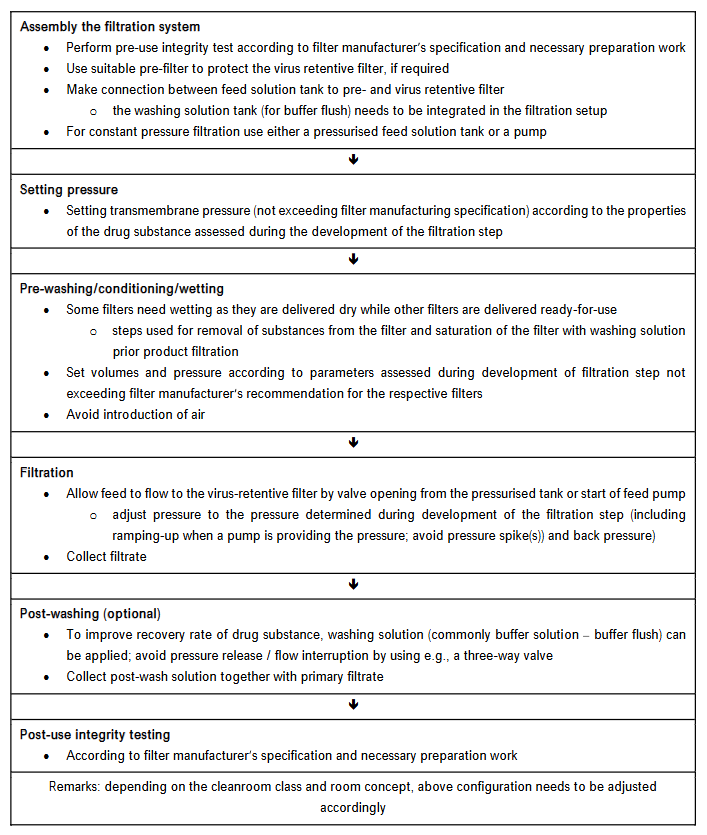

The composition of virus retentive filters differs, especially regarding the membrane/hollow fibre material. Based on the information provided by the filter manufacturer, extractables and leachable as well as endotoxins are considered low and, therefore, comparable between different filters. Potential sorption of components of the drug substance to the filter material may, if it occurs, cause a competitive adsorption interaction between the membrane and virus vs. product intermediate impacting the virus clearance capacity and may be comparable between different virus retentive filters of the same membrane chemistry but should be studied regarding yield and change in key impurity composition as well as virus clearance capacity. Prior knowledge of product and process with respect to physicochemical and biological properties of the drug substance is also applicable regarding potential modification of drug substance/product when changing filter materials. Based on these criteria, the potential risk regarding quality and safety of the product due to changing a virus retentive filter is considered remote. The virus clearance capacity should increase or remain at least comparable to the currently used filter even under pressure release/flow interruption events and other robustness conditions; commonly changing a filter results in increased filter load per area and decreased filtration time for a given volume. Also, this parameter should be assessed in virus clearance studies, especially considering a reasonable virus load in the spiked product intermediate as an overload of a filter with viruses, including non-infectious virus particles, could result in a virus breakthrough. Confirmatory virus clearance studies covering the differences in filtration parameters, primarily with worst-case viruses as parvoviruses, have to be performed with the new filter employing the relevant product intermediate. Such paradigmatic product-specific studies have also to be performed when prior knowledge, e.g., a platform validation approach, was established for the current filter for the parameters affecting the virus removal capacity, as the new filter will have different filtration parameters as transmembrane pressure and load of intermediate/filter area. In conclusion, the risk assessment identifies potential risks when changing the currently implemented filter for the new filter (including, if applicable, avoidance or usage of pre-filters). A potential risk is a (slightly) altered composition of the drug substance by removing large accompanying proteins or lipoproteins potentially present in the drug substance prior to the virus filtration step potentially resulting in a change in the chemical properties of the drug substance to a certain but considered low degree. As disclosed in the ICH Q6B guideline, the specifications based on characterisation, physicochemical properties, biological activity, immunochemical properties, purity, impurities and contaminants and quantity have to be determined for the drug substance and drug product filtered through the currently implemented filter; these specifications have to be closely comparable to the parameters obtained after changing the virus retentive filter. A flow chart of the virus filtration step is shown in Figure 3.

4.1.2 Risk Control, Reduction and Acceptance

A potential risk to the quality, safety and efficacy of the drug product, due to the exchange of the currently implemented virus retentive filter by the new filter, is determined by appropriate process validation using prior knowledge regarding analytical methods for characterisation of the drug substance/drug product. If, under unlikely circumstances, considerable modifications of the physicochemical and biological properties of the drug substance would be detected, the filtration parameters as transmembrane pressure including pressure decay over time, use or avoidance of a prefilter, using or avoiding a buffer flush, or the temperature used during filtration could be adjusted to meet the predefined criteria/specifications of the drug substance and drug product. Based on publicly available information (for newly developed virus retention filters by the filter manufacturer), the virus reduction capacity of the new filter to be implemented is more robust than and/or exceeds that of the currently used filter. Nevertheless, confirmatory virus clearance studies covering the differences in filtration parameters as increased transmembrane pressure and larger volume/filter area, have to be performed with the new filter, primarily with worst-case viruses as parvoviruses employing the relevant product intermediate.

The output of the risk assessment is often expressed qualitatively, i.e., high, medium, or low risk and the subsequent risk control includes decision making to reduce and/or accept risks (when the risk is at an acceptable level). Mitigation or avoidance of quality risk has to be initiated when it exceeds a specified (acceptable) level. Risk acceptance could be a formal decision to accept a residual risk, e.g., a very low amount of infectious small viruses in the filtrate of a small virus retentive filter, documented in virus validation studies performed within the limit of process specifications. Such a result would not change the overall virus safety approach of a specific product when the (LRF) by the virus retentive filter is high enough to meet the pre-defined minimal overall LRF for a given product. When the filtration is performed within pre-defined specifications and no failure was detected in the pre- and post-filtration filter integrity test, no further risk control activities are necessary.

The principle of a Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP), a systematic, proactive, and preventive tool for assuring product quality, reliability, and safety is shown in Table 2. Based on this risk assessment performed it is expected that the change of the virus retentive filters is not adversely impacting the drug substance and the drug product. Nevertheless, the acceptance of a potential risk is based on meeting the product specifications and acceptance criteria defined for the current filtration step also after change to the new filter. Based on all this information, including the HACCP assessment, corrective actions are not required when the product quality and safety remains unchanged (potentially after adaptation of the filtration parameters to the new filter).

4.1.3 Risk Review

Risk management should be an ongoing part of the quality management process, and the output/results of the risk management process should be reviewed to take into account new knowledge and experience. This process should continue to be utilised for events that might impact the original quality risk management decision, whether these events are planned (e.g., results of product review, inspections, audits, change control) or unplanned (e.g., root cause from failure investigations, recalls) and, therefore, the risk review might result in a reconsideration of risk acceptance decisions.

4.2 PHARMACEUTICAL QUALITY SYSTEM

The ICH Q10 Pharmaceutical Quality System covers the entire lifecycle of a product including pharmaceutical development, technology transfer, commercial manufacturing, and product discontinuation. The major pillars under the comprehensive PQS model are (i) process parameters and product quality monitoring system, (ii) corrective action / preventive action (CAPA) system, (iii) change management system, and (iv) management review. Knowledge management and quality risk management are applicable throughout the lifecycle of a product. Such an effective pharmaceutical quality system that is based on International Standards Organisation (ISO) quality concepts, includes applicable Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) regulations and the ICH Q7 guideline and complements ICH Q8 Pharmaceutical Development and ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management. The objectives of the ICH Q10 guideline, complementing or enhancing regional GMP requirements are (i) achieving product realisation, (ii) establishing and maintaining a state of control by developing and using a Quality Risk Management (QRM) system for process performance and product quality, thereby providing assurance of continued suitability and capability of processes, and (iii) facilitating continual improvement by identification and implementation appropriate product quality improvements, process improvements, variability reduction, innovations and pharmaceutical quality system enhancements, thereby increasing the ability to fulfil quality needs consistently. Quality risk management can be useful for identifying and prioritising areas for continual improvement. Knowledge management and quality risk management enables the manufacturer of drug products to implement ICH Q10 effectively and successfully. The senior management has the ultimate responsibility to ensure that an effective pharmaceutical quality system is in place to achieve the quality objectives, and that roles, responsibilities, and authorities are defined, communicated and implemented throughout the company.

4.3 REGULATORY GUIDANCE REGARDING CHANGE CONTROL

The ICH Q5E guideline outlines the goal of the comparability exercise to ascertain that pre- and post-change drug product is highly similar in terms of quality, safety, and efficacy. The virus filtration step has to be evaluated regarding changes in the quality attributes comparing the pre- and post-change of the drug substance / product intermediate. Considering the quality of the drug substance / drug product, appropriate analytical techniques have to be applied. In order to detect minor modifications, the analytical methods should be extended from standard in-process control tests to tests used during the development of the production process. The characterisation of the product (according to ICH Q6B) includes physicochemical properties, biological activities, immunochemical properties, and purity, impurity, and contaminants. Potential changes in the stability of the post-change product are considered remote but the requirement for stability studies (re-test period for the drug substance and shelf life for the drug product) should be discussed with the relevant regulatory authorities. ICH Q7 includes a paragraph on Change Control stating that a formal change control system should be established to evaluate all changes with written procedures for identification, documentation, appropriate review, and approval of changes. Proposals for GMP relevant changes, as exchange of virus retentive filters, should be drafted, reviewed, and approved by the appropriate organisational units of the manufacturer. Scientific judgement should determine what additional testing and validation studies are appropriate to justify a change in a validated process. After the change has been implemented, the first batches produced should be evaluated.

ICH Q12 describes Established Conditions, Post-Approval Change Management Protocol (PACMP), Product Lifecycle Management (PLCM) Document, Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS) and Change Management, Relation between Regulatory Assessment and Inspection, Structured Approaches for Frequent CMC Post-Approval Changes, and Stability Data Approaches to support the evaluation of CMC changes; the topics of this guideline relevant for changes of virus retentive filters are already discussed above.

5. Conclusion

Changes to manufacturing processes are frequently made for biotechnological / biological products to improve manufacturing processes regarding e.g., improved yield, purity, virus safety, decreased costs, and time required for a certain manufacturing step. When during the development of a virus filtration step already an alternative filter was studied and all relevant data are part of the marketing authorisation application (MAA), the use of this alternative filter is not a change. Replacing virus retentive filters is intended to meet filter supply issues or to implement improved filters with decreased time required for the filtration of a batch of product due to increased TMP and volume/filter area, and improved, robust virus removal capacity of the filtration step for small non-enveloped viruses as parvoviruses. Considering the regulatory guidance, the risk to product quality due to the change of the virus filter is assumed to be low as (i) instructions are provided by the filter manufacturers how to implement the filter (and these instructions will have to be followed), (ii) practically identical physicochemical and biological properties of the pre- and post-change product will be achieved demonstrated by employing analytical methods used during the development of the filtration step and in routine in-process testing, and (iii) the virus removal capacity is considered to be increased and more robust having been demonstrated in virus clearance studies. Table 3 outlines activities relevant for post-approval change of virus retentive filters with experimental studies covering the virus removal capacity (to be the same or improved) and the unmodified properties of the drug substance/product after the filter exchange. Regulatory guidance is recommended when the change is initiated. Notification of the change to regulatory authorities have to be performed according to the guidance by the respective relevant regulatory authorities.

Table 3: Exemplary Outline of Activities for Post-Approval Change of Virus Retentive Filters

| Documents | Detailed Information in document | Required experimental studies to support change |

|---|---|---|

| Post Approval Change Management Protocol (PACMP) | Detailed description of proposed change including rational | Perform science-based Risk Assessment considering the impact of change on product quality |

| Initial risk assessment proposes specific studies to be performed to mitigate or manage potential risk for product | Virus clearance studies employing the relevant, product-specific intermediate have to demonstrate a robust, effective virus reduction capacity of the new filter at least as high as the currently implemented virus retentive filter. The removal of small viruses as parvoviruses under the modified conditions (increased pressure and volume of intermediate (and buffer flush, if used)/filter area) is the primary focus of such studies | |

| Product Life Cycle Management (PLCM) document | Outlines the specific plan for product lifecycle management that includes the ECs, reporting categories for changes to ECs, PACMPs (if used) and any post-approval CMC commitments | |

| Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS) | PQS described in ICH Q10 Pharmaceutical Quality System is based on International Standards Organisation (ISO) quality concepts, includes applicable Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) regulations and complements ICH Q8 Pharmaceutical Development and ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management |

References

- Virus Retentive Filtration. Technical report No. 41 (Revised 2022). Parenteral Drug Association. 2022

- Brorson K, Sofer G, Aranha H. Nomenclature standardization for large pore size virus-retentive filters. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol 2005;59(6):341-345.

- Lute S, Riordan W, Pease LF 3rd, et al. A consensus rating method for small virus-retentive filters. I. Method development. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol 2008;62(5):318-333.

- Brorson K, Lute S, Haque M, et al. A consensus rating method for small virus-retentive filters. II. Method evaluation. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol 2008;62(5):334-343.

- Gröner A. Virus Retentive Filters – Effective Virus Removal in the Manufacturing Process of Biologicals. Med Res Arch [online] 2024;12(12). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i12.6084

- ICH Harmonised Guideline. Viral Safety Evaluation of Biotechnology Products Derived from Cell Lines of Human or Animal Origin, Q5A(R2), 1 November 2023.

- ICH Harmonised Guideline. Technical and Regulatory Considerations for Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle Management, Q12, 20 November 2019.

- Ramnarine E, Vinther A, Bruhin K, et al. Effective management of post-approval changes in the pharmaceutical quality system (PQS) through enhanced science and risk-based approaches industry One-Voice-of-Quality (1VQ) solutions. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol. 2020.

- Deavon A, Adam S, Ausborn S, et al. Path forward to optimise post-approval change management and facilitate continuous supply of medicines and vaccines of high quality worldwide. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2023;57:7-11.

- ICH Harmonised Guideline. Pharmaceutical Development, Q8(R2), August 2009.

- ICH Harmonised Guideline. Quality Risk Management, Q9(R1), 18 January 2023.

- ICH Harmonised Guideline. Pharmaceutical Quality System, Q10, 4 June 2008.

- ICH Harmonised Guideline. Development and Manufacturing of Drug Substances (Chemical Entities and Biotechnological/Biological Entities, Q11, 1 May 2012.

- FDA. Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls Changes to an Approved Application: Certain Biological Products-Guidance for Industry. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, December 2017.

- EMA/CHMP/CVMP/QWP/586330/2010. Questions and answers on post approval change management protocols. 30 March 2012.

- ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Good Manufacturing Practice Guide for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients, Q7, 10 November 2000.

- TRS 908 37th report on the WHO Expert Committee on Specifications for Pharmaceutical Preparations. Annex 7 Application of Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) methodology to pharmaceuticals.

- Lute S, Bailey M, Combs J, Sukumar M, Brorson K. Phage passage after extended processing in small-virus-retentive filters. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2007;47(Pt 3):141-151.

- Ajayi OO, Johnson SA, Faison T, et al. An updated analysis of viral clearance unit operations for biotechnology manufacturing. Curr Res. Biotechnol. 2022;4:190-202.

- Ajayi OO, Cullinan JL, Basria I, et al. Analysis of virus clearance for biotechnology manufacturing processes from early to late phase development. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol 2025;79:252-270.

- Roth NJ, Dichtelmüller HO, Fabbrizzi F, et al. Nanofiltration as a robust method contributing to viral safety of plasma-derived therapeutics: 20 years’ experience of the plasma protein manufacturers. Transfusion 2020;60(11):2661-2674.

- Miesegaes G, Lute S, Brorson K. Analysis of virus clearance unit operations for monoclonal antibodies. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;106(2):238-246.

- Afzal MA, Peles J, Zydney AL. Comparative analysis of the impact of protein on virus retention for different virus removal filters. Membranes 2024;14:158.

- ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Comparability of Biotechnological/Biological Products Subject to Changes in their Manufacturing Process, Q5E, 18 November 2004.

- ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Specifications: Test procedures and acceptance criteria for biotechnological/biological products, Q6B, 10 March 1999.

- Kayukawa T, Yanagibashi A, Hongo-Hirasaki T, Yanagida K. Particle-based analysis elucidates the real retention capacities of virus filters and enables optimal virus clearance study design with evaluation systems of diverse virological characteristics. Biotechnol Prog 2022;38:e3237.