Swiss Postpartum Screening Tool for Depression Detection

Development of the Swiss postpartum Screening tool (SPST) for the early detection of postpartum depression

Stadlmayer W.¹, Chicherio R.², Giovannini-Spinelli M.³, Amsler F.⁴

- Gynaecologist/ obstetrician/ psychotherapist, Institution: private practice “Geburt und Familie”, Aarau, Switzerland

- Psychologist/ psychotherapist/ lecturer, Institution: ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, IAP Institute of Applied Psychology

- Gynaecologist/ obstetrician/ expert in psychosomatics, Institution: private practice “Geburt und Familie”, Aarau, Switzerland

- Psychologist/ scientific statistician, Institution: private company “amsler consulting”, Switzerland

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 May 2025

CITATION: Stadlmayer W., et al., 2025. Development of the Swiss postpartum screening tool (SPST) for the early detection of postpartum depression and acute stress reaction. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(5).

https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6302

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6302

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Postpartum depression and posttraumatic development have emerged as leading causes of maternal mortality in Western countries during the first year after childbirth, as evidenced by the increasing number of suicides during this period. Consequently, there is an urgent need to screen for postpartum depression and acute stress reactions following delivery. Early screening—ideally within the first few days postpartum—with the goal of identifying women at risk by the third week may allow for timely and effective preventive interventions.

Methods: In a sample of 209 participants, the predictive value of various factors – including birth-related parameters, birth experience (SILGer12), team support (BBCI), depressive symptoms (EPDS), and acute stress responses (IES) – was evaluated using correlation analyses and stepwise logistic regression modeling.

Results: The Swiss Postpartum Screening Tool (SPST) demonstrated a sensitivity of 91.9%. The SILGer12 and two key items from the Impact of Event Scale (IES) proved effective in identifying women with acute stress reactions by the third postpartum week. One (out of four) team support items and two items from the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) were predictive of postpartum depression at the same time point.

Discussion and Conclusion: The screening method developed in this study appears to be a promising approach, demonstrating high sensitivity and ease of implementation during the first postpartum week, ideally between days 2 and 5. Further validation in larger, more diverse samples is recommended to address the small number of at-risk women (n = 5) who were not detected using this approach.

Keywords

- Postpartum depression

- Screening tool

- Acute stress reaction

- Maternal health

Introduction

Maternal suicide has emerged as a leading cause of postpartum mortality in Western countries. The Sixth Report of Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom identified suicide as the primary cause of indirect maternal deaths during 2000–2002¹. Recent analyses suggest that, when considering the entire first postpartum year, suicide may surpass traditional biological causes of maternal death, such as hemorrhage, embolism, infection, and eclampsia²,³,⁴. Postpartum psychological disorders predominantly encompass depressive symptoms and acute stress reactions (ASR), excluding rare psychotic episodes (~0.1%). While postpartum depression has been extensively studied, ASR – potential precursors to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – have gained recognition. Depressive symptoms affect approximately 20% of new mothers⁵, whereas ASR may occur in up to 30%⁶,⁷. PTSD correlates strongly with depression (r = 0.6) and is linked to impaired coping and heightened stress⁸. Despite some symptom overlap, depressive and stress-related responses are distinct. Gürber et al.⁹ reported minimal co-occurrence (<10% in week 1; <1% in week 3). Stadlmayer et al.¹⁰,¹¹ found that approximately 30% of postpartum women exhibit clinically significant depressive or stress-related symptoms within the first three weeks. Notably, reliance on a single assessment tool, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) or the Impact of Event Scale (IES), may overlook about one-third of affected individuals. Early identification of psychological distress postpartum is crucial for timely intervention and prevention of chronic conditions. Early postpartum assessments can detect acute needs, including suicidal ideation, and facilitate support for mother-infant bonding and family dynamics¹². Negative birth experiences are associated with both depressive symptoms and ASR¹³,¹⁴. However, this relationship is not necessarily causal. For instance, Manzano et al.¹⁵ observed varied depression trajectories from pregnancy to postpartum. Meta-analyses indicate that subjective distress during labor, operative deliveries, lack of support, and prenatal depression are significant PTSD risk factors¹⁶. Importantly, even uncomplicated deliveries can result in ASR, underscoring the impact of individual perceptions¹⁴. Given the significance of postpartum psychological health and the benefits of early intervention, this study proposes a stepwise screening protocol to assess postnatal depression and acute stress reactions with high sensitivity, aiming to identify women requiring immediate care.

Method

Recruitment and patient sample: The survey ‘birth experience and psychological adaptation postpartum’ had been approved by the Basel ethics committee, and participants (n = 251) gave their written informed consent. The only exclusion criterion was insufficient knowledge of German, reducing the eligible portion of patients by approximately 50%, due to the high percentage of migrants at this Basel obstetric clinic, who tend to use the clinic because minimal basic health insurance does not cover treatment in other regional hospitals without top-up payment. Recruitment by mainly female researchers (students and doctors) was undertaken three times during the research project, but with various additional foci, from July 1997 to January 1999. We studied the birth experience and postpartum adaptation, using a basic common set of assessment tools, with a primary focus (i) on women with vaginal deliveries (A: n = 62), (ii) on first-time mothers and their transition to parenthood (B: n = 80), and (iii) on the subjective experience of obstetric interventions (C: n = 109). Women were canvassed about participation either after delivery (A & C) or during pregnancy (B). Thus, of about 2000 women attended at this clinic from July 1997 to January 1999, about 1000 spoke German sufficiently well to be eligible. Due to the fact that recruitment was limited to certain days of the week for technical reasons only about 25% of these were finally recruited. Maternal age ranged from 15.8 yrs to 43.1 yrs (mean: 31.0 yrs), with 63% of parturients having their first child. The partners’ presence during labor was higher than 95% (of all parturients: n = 251). The usual setting in the

delivery room was the one-to-one situation: one midwife was in charge of one parturient in labour. The service of this university hospital includes all medical standards available in modern obstetrics. Epidural blocks were usually only applied upon request. Obstetric data collected from the patient records show that the distribution of modes of delivery and epidural blocks are comparable to those at the Basel University Hospital at the time¹⁷ with a slightly higher proportion of assisted vaginal deliveries (+5%) and of primiparae (+15%), and a lower proportion of caesareans (−5%) in the study sample (tables 2a & b). With only 8.8% of preterm infants (n = 22), our sample (male = 47.6%, female = 52.4%) is characterized as low-risk with low morbidity and mortality (n = 0) in the neonatal period. In 209 subjects the complete data set (birth experience, depression week 1 and 3, stress reaction week 1 and 3) is available. Thus, the results presented in this work are based on the data analysis of these 209 subjects. Of these 63.6% (n = 133) were primiparae and 62.2% (n = 130) had no epidural anesthesia; the mode of delivery was distributed as follows: 70.8% (N = 148) spontaneous, 17.7% (n = 37) assisted, 5.3% (n = 11) elective section, and 6.2% (n = 13) unplanned c-section; the vast majority of newborns 85% (n = 179) weighed 2500–3999gr, whereas in 6.2% (n = 13) the birth weight was higher, and in 8.1% (n = 17) it was lower. Birth duration was assessed in n = 195 with the beginning of birth defined by one of the following four parameters: subjective beginning of labor, rupture of membranes, transport into OT (in case of elective c-section), beginning of induction); birth duration was 12 hours, or less, in 59.5% (n = 116), and longer than 12 hours in 40.5% (n = 79).

INSTRUMENTS

Assessment of maternal birth experience: In the assessment of maternal birth experience the questionnaire SILGer (Salmon’s Item List – German language version) has been widely used since its publication in 2001¹⁸. Schlumpf-van Waardenburg & Wächli¹⁹ showed that this tool has been integrated into various research projects in at least 54 papers published or publicly accessible. The SILGer as a questionnaire has been published for the first time in 1990 and 1992 by Salmon et al.¹⁹,²⁰, and replicated in a German-language version in 2001¹⁷; both tools (the English original and the German translation) have the same wording (see table 1), yet with a different factor structure¹⁷. The reliability of the overall score is reported as .87. The questionnaire is built up out of 20 items, to be answered on a Likert-scale from 1 to 7; the maximum score is 120 (i.e. max. score of 140 minus 20), and the cut-off to differentiate a positive from a negative birth experience is 70 (i.e. 70, or below means ‘negative’). Time of assessment is 24 to 48 hrs postpartum; however, this tool may also be used to assess long-term memory of the birth experience in the 2nd year after birth²¹. In this work we use the sum-score of a short version SILGer12 with an internal reliability of .83 (C’alpha). Both scales are highly interrelated with a Pearson’s r of .97.

Assessment of maternal postnatal depression: Maternal depression was assessed using the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS)²²,²³,²⁴ (see Table 2). This well-established 10-item screening tool rates the frequency of symptoms experienced during the past week on a four-point scale (0–3). Items vary between positively and negatively worded, and scoring is adjusted accordingly. The overall score of this scale is clinically interpreted as follows: 9, or lower, no depression; 10–12, intermediate symptoms, follow-up is indicated; 13, or higher, clinically significant depression, immediate support is indicated (table 2);

Assessment of maternal postnatal acute stress reaction: Acute stress reactions were assessed using the Impact of Event Scale (IES)²⁴,²⁵ (see Table 3). Although a revised version, the IES-r, is now available²⁶, we chose the original 15-item IES to maintain consistency with the initial study design (1996–1997) and due to its high correlation with the IES-r, i.e. both sum-scores are highly interrelated with a Pearson’s r from .92 to .94 in week 1, 2 and 3, respectively²⁷. The questionnaire (table 3), which is a well-established 15-item scale²⁸ records intrusion

(7 items C’alpha: .78) and avoidance (8 items, C’alpha: .82) on two subscales (subscale-to-subscale correlation: .42). Items are rated on a four-point scale (0, 1, 3, and 5) to answer ‘how often they were experienced’ within the last week. The IES is capable of differentiating assessments performed within a one-week period. Since high IES-levels at week three postpartum indicate a delayed decline in stress reaction²⁷, we refer to this time point to assess postnatal adjustment. The scale is clinically interpreted as follows: 9, or low, no risk of traumatic stress, 10–20, intermediate risk to develop traumatic stress reactions, follow-up is indicated; 21, or higher, acute stress reaction, immediate support is indicated. Assessment was performed at three weeks postpartum, since high IES levels at this time point suggest a delayed stress recovery.

Table 1: Salmon’s Item List – German language version SILGer12¹ (Short version of SILGer20)

Please, tick the value from 1 to 7 in each item which best describes how you felt during the whole birthing process, including the first hours after birth; if certain items changed considerably during this time, please tick the average value of the item that best represents the overall experience².

Item (SILGer20) | Positive Pole | Rating Scale | Negative Pole

1 (1) — disappointed — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — not disappointed

2 (3)* — enthusiastic — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — not enthusiastic

3 (5)* — delighted — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — not delighted

4 (6) — depressed — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — not depressed

5 (7)* — happy — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — not happy

6 (9)* — good experience — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — bad experience

7 (10)* — coped well — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — did not cope well

8 (12)* — in control — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — not under control

9 (15) — anxious — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — not anxious

10 (16) — painful — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — not painful

11 (18)* — time going fast — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — time going slowly

12 (19) — exhausted — 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 — not exhausted

The following items omitted from SILGer20: 2 (fulfilled), 4 (satisfied), 8 (excited), 11 (cheated), 13 (enjoyable), 14 (relaxed), 17 (easy), 20 (confident)

In brackets: Item number in SILGer20

-

Sum-score: To calculate the sum-score the items 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, 18 must be transformed by 8−x (x = score ticked by participant); then, the mean of the items actually rated must be multiplied by 12, and finally, the resulting product reduced by 12 to allow 0 as the minimum score (maximum score = 72)

(1) The short version – 12 items – should only be used to assess the ‘overall birth experience’, as the internal consistency on subscale levels is not sufficient with only 12 items.

(2) Please note: The patient’s introductory instructions are part of the questionnaire;

Table 2: Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale EPDS

Item | Statement | Response Options (Score)

01 | I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things | As much as I always could (0); Not quite so much now (1); Definitely not so much now (2); Not at all (3)

02 | I have looked forward with enjoyment to things | As much as I ever did (0); Rather less than I used to (1); Definitely less than I used to (2); Hardly at all (3)

03 | I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong | Yes, most of the time (3); Yes, some of the time (2); Not very often (1); No, never (0)

04 | I have been anxious or worried for no good reason | No, not at all (0); Hardly ever (1); Yes, sometimes (2); Yes, very often (3)

05 | I have felt scared or panicky for no good reason | Yes, quite a lot (3); Yes, some of the time (2); Not much (1); No, not at all (0)

06 | Things have been getting to me | Yes, most of the time I haven’t been able to cope at all (3); Yes, sometimes I haven’t been coping as well as usual (2); No, most of the time I have coped quite well (1); No, I have been coping as well as ever (0)

07 | I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping | Yes, most of the time (3); Yes, sometimes (2); No, not very often (1); No, not at all (0)

08 | I have felt sad or miserable | Yes, most of the time (3); Yes, quite often (2); Not very often (1); No, not at all (0)

09 | I have been so unhappy that I have been crying | Yes, most of the time (3); Yes, quite often (2); Only occasionally (1); No, never (0)

10 | The thought of harming myself has occurred to me | Yes, quite often (3); Sometimes (2); Hardly ever (1); Never (0)

The wording of the scoring template is shown within the questionnaire itself, but not the scoring numbers, according to standard guidelines. Please note: overall scores are calculated by multiplying the mean by 10 (range from 0 to 30) (Stanford Medicine 2025).

https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/ppc/documents/DBP/EPDS_text_added.pdf download 19/4/2025

Table 3: Impact-of-Event Scale IES

Item No. | IES-r Mapping | Subscale (I/A) | Item Statement | Response Options (Score: 0, 1, 3, 5)**

01 | 06 | I | I thought about it when I didn’t mean to | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

02 | 05 | A | I avoided letting myself get upset when I thought about it or was reminded of it | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

03 | 17 | A | I tried to remove it from memory | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

04 | 02 & 15* | I | I had trouble falling asleep or staying asleep because of pictures or thoughts about it that came into my mind | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

05 | 16 | I | I have waves of strong feelings about it | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

06 | 20 | I | I had dreams about it | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

07 | 08 | A | I stayed away from reminders of it | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

08 | 07 | A | I felt as if it hadn’t happened or wasn’t real | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

09 | 22 | A | I tried not to talk about it | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

10 | 09 | I | Pictures about it popped into my mind | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

11 | 03 | I | Other things kept making me think about it | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

12 | 12 | A | I was aware that I still had a lot of feelings about it, but I didn’t deal with them | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

13 | 11 | A | I tried not to think about it | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

14 | 01 | I | Any reminder brought back feelings about it | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

15 | 13 | A | My feelings about it were kind of numb | Not at all; Rarely; Sometimes; Often

IES-r: Impact-of-Event scale, revised: 22 items (with additional subscale ‘hyperarousal’, not presented here): The items of the IES and IES-r correspond to each other in the indicated way IES: (I); seven intrusion items (C’alpha: .78); (A) eight avoidance items (C’alpha: .82); split-half reliability of sum-score: .86; subscale-to-subscale correlation: .42.

* IES-4 is bifurcated into 2 items in IES-r: 02 (I had trouble staying asleep – intrusion) and 15 (I had trouble falling asleep – hyperarousal).

** Please note: The scoring template in the IES (0,1,3,5) is different from the one used in the IES-r (0,1,2,3,4); the overall score is calculated by multiplying the mean of the items actually answered by 15 (range from 0 to 75).

Assessment of ‘perceived team support during childbirth’: Perceived team support was assessed using four items from the unpublished Berne-Basel Childbirth Inventory (BBCI)²¹: BBCI 27: “Team made me feel secure” BBCI 28: “Team cooperating well in medical aspects” BBCI 29: “Team harmonizing well emotionally” BBCI 30: “Team were integrated partner” (negatively phrased). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = best performance; 5 = worst performance). The overall score demonstrates good internal reliability with a C’alpha of .85, and an item-to-scale correlation from .67 to .97.

Statistical procedures

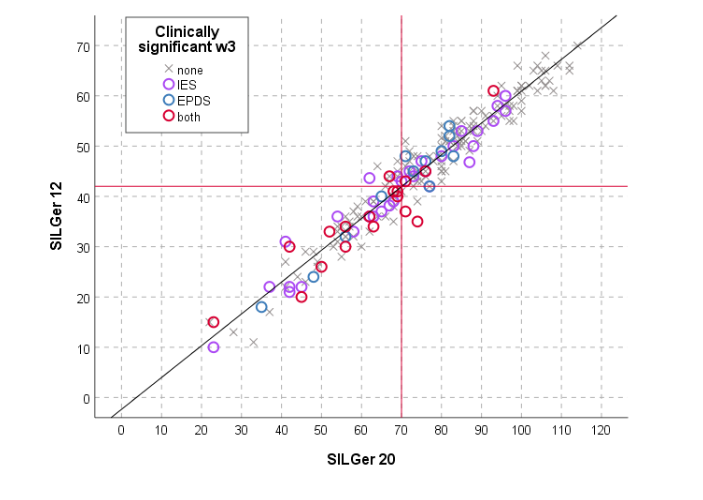

Descriptive statistics were computed, and associations were examined using Pearson’s r for continuous variables, point-biserial correlations if one of the variables is dichotomous and phi coefficients for associations between two dichotomous variables. Because all are mathematically equivalent to Pearson’s, they were not distinguished in the results. Stepwise logistic regression analyses were subsequently performed. Predictive performance was assessed using sensitivity (the proportion of correctly identified positive cases) and specificity (the proportion of correctly identified negative cases). To compare the equivalent value of two versions of SILGer we used a scatter plot.

Initially, we focused on the identification of parameters individually associated with postpartum depression and/or acute stress reaction at three weeks postpartum. The overarching goal was to develop a screening tool that, in addition to the SILGer, minimizes the number of questions while maximizing sensitivity for detecting women at risk for depression and/or acute stress reactions three weeks after birth, based on assessments conducted within the first days after birth. Through a stepwise combination of significantly correlated predictors, we aimed to maximize the correct identification of at-risk women.

Results

Characteristics of the questionnaires in the sample are described in Table 4. To identify potential predictors of depressive symptoms and acute stress at week 3, we examined correlations with relevant parameters, i.e. obstetric parameters, SILGer12, team support, and IES & EPDS in week 1. Among the objective birth variables, only birth duration—using a cut-off of 12 hours—was associated with both IES and EPDS scores. Parity was associated with IES only, and mode of delivery showed no correlation with either outcome. Birth experience (SILGer12) and team support item BBCI 29 were associated with both IES and EPDS, while BBCI 27 was associated only with EPDS. The other BBCI items showed no significant associations. In terms of distribution, 88.9% of respondents rated BBCI 27 with a score of 1 or 2 (positive team support), and 87.2% did so for BBCI 29. At week 3 postpartum, the majority of women (70.3%, n = 147 of 209) reported no symptoms of depression or acute stress. Subsequently, 29.7% women reported psychological distress: 15.3% exhibited acute stress, 5.7% showed depressive symptoms, and 8.6% had both. To evaluate the equivalence of the two birth experience scales, SILGer12 and SILGer20 were compared using a scatter plot (Chart 1). The correlation was high (Pearson’s r = 0.97). Each version failed to identify two women who were classified as positive on IES or EPDS by the alternate version, indicating that SILGer12 can effectively substitute SILGer20. From the initial analysis, the following predictors were identified as potentially useful for detecting stress and depression at week 3: birth duration >12 hours, SILGer12 score ≤42, perceived team support (BBCI 27 and/or 29), and elevated IES or EPDS at week 1. Specifically, week 1 IES and EPDS correlated with week 3 outcomes at r = .56 and r = .49, respectively (both p < .001).

Branch A – Focus on IES >9 at Week 3 Step 1: A stepwise logistic regression analysis (Table 5) revealed that only IES at week 1 and SILGer12 were predictive of IES >9 at week 3. Step 2: Combining IES >9 (week 1) and SILGer12 ≤42 yielded a sensitivity of 92.0% (46 of 50 true positives) and a specificity of 45.3% (72 of 159 true negatives). Step 3: To reduce the number of screening items, we

tested individual IES items for correlation with IES >9 at week 3. Only IES item 04 (“I had trouble falling asleep…”) lacked significant association (Table 6). Step 4: The most predictive IES items were 02, 07, 10, and 11. Optimal cut-off values were identified through efficiency-based selection. The combination of items 10 (score 1, or higher) and 11 (score 3 or 5) with SILGer12 ≤42 improved sensitivity to 92%.

Table 4: statistical characteristics of SILGer, IES and EPDS

Mean Scores, Standard Deviations, and Ranges for Birth Experience (SILGer), Trauma (IES), and Depression (EPDS) (N = 209)

Outcome Measure | SILGer20 (Birth Experience) | SILGer12 (Birth Experience) | IES Week 1 (Trauma) | IES Week 3 (Trauma) | EPDS Week 1 (Depression) | EPDS Week 3 (Depression)

Mean | 74.8 | 45.0 | 11.6 | 7.3 | 5.4 | 5.3

Median | 76.0 | 45.0 | 10.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 5.0

Standard Deviation | 19.2 | 12.5 | 9.2 | 7.1 | 4.6 | 4.3

Minimum / Maximum | 22 / 114 | 10 / 70 | 0 / 55 | 0 / 37 | 0 / 24 | 0 / 23

Chart 1: Scatter plot SILGer12 (cut-off ≤ 42) versus SILGer20 (cut-off ≤ 70) showing correlation in identifying cases with EPDS >9 and IES >9 at week 3 postpartum.

Table 5: stepwise regression to predict IES week 3 (variables in model: SILGer12 ≤ 42; EPDS, IES, team support, birth duration >12h) Predicted IES >9 week 3 (n = 209)

Model | Predictor Variable | B | P-value | Odds Ratio [Exp(B)] | 95% CI (Lower–Upper) | Nagelkerke R²

1 | IES > 9 at Week 1 | 2.07 | .000 | 7.9 | 3.31 – 18.87 | 0.23

2 | SIL ≤ 42 | 0.87 | .016 | 2.38 | 1.17 – 4.82 | 0.27

Constant | -2.90 | .000 | 0.06

Note: The other parameters (EPDS >9, BBCI 27, and birth duration >12hrs) did not contribute to the model.

Table 6: correlations (Pearson’s r) – IES-items (week 1) with IES >9 (week 3)

Item No. | Subscale (Type) | Item Description | Correlation (r)

01 | I | I thought about it when I didn’t mean to | 0.30***

02 | A | I avoided letting myself get upset when I thought about it or was reminded of it | 0.32***

03 | A | Other things kept making me think about it | 0.35***

04 | I | I had trouble falling asleep or staying asleep because of pictures or thoughts about it | 0.08

05 | I | I have waves of strong feelings about it | 0.26***

06 | I | I had dreams about it | 0.31***

07 | A | I stayed away from reminders of it | 0.37***

08 | A | I felt as if it hadn’t happened or wasn’t real | 0.17*

09 | A | I tried not to talk about it | 0.31***

10 | I | Pictures about it popped into my mind | 0.28***

11 | I | Other things kept making me think about it | 0.35***

12 | A | I was aware that I still had a lot of feelings about it, but I didn’t deal with them | 0.35***

13 | A | I tried not to think about it | 0.39***

14 | I | Any reminder brought back feelings about it | 0.33***

15 | A | My feelings about it were kind of numb | 0.23***

Note:

Subscales: I = Intrusion, A = Avoidance

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Branch B – Focus on EPDS >9 at Week 3 Step 1: A stepwise logistic regression (Table 7) was conducted using EPDS >9 and >6 as predictive factors. The model including EPDS >6 and BBCI 27 >2 yielded the best predictive value (Nagelkerke R² = 0.37).

Step 2: Combining EPDS >6 (week 1) and BBCI 27 >2 identified 26 of 30 true positives (sensitivity = 86.7%) and 125 of 159 true negatives (specificity = 78.6%).

Step 3: All EPDS items at week 1 were significantly correlated with EPDS >9 at week 3 (Table 8).

Step 4: Items 02, 03, and 07 were the most predictive. Cut-off scores of ≥2 for EPDS 03 and ≥1 for EPDS 07 yielded the best detection-to-inclusion ratio. Combining these with BBCI 27 improved sensitivity to 93.3% and specificity to 65.9%.

Summary: The final screening model, the Swiss Postpartum Screening Tool (SPST), includes: SILGer-12 (birth experience), BBCI 27 (team support), IES items 10 & 11 (acute stress), EPDS items 03 & 07 (depression). Applying this tool would select 147 of 209 women (70.3%) for re-evaluation at week 3: 58 for IES only (27.8%), 26 for EPDS only (12.4%), and 63 for both (30.1%). This approach identifies 57 of the 62 women requiring support (sensitivity = 91.9%) and correctly excludes 62 of 147 (specificity = 42.2%) (Table 9).

Table 7: stepwise regression to predict EPDS week 3 (variables in model: SILGer12 ≤42; EPDS, IES, team support, birth duration >12h) Predicted EPDS >9 week 3 (n = 209)

Model | Predictor Variable | B | p-value | Odds Ratio [Exp(B)] | 95% CI (Lower–Upper) | Nagelkerke R²

1 | EPDS > 6 (Week 1) | 2.71 | .000 | 15.05 | 5.32 – 42.61 | 0.32

2 | BBCI 27 > 2 | 1.55 | .006 | 4.73 | 1.55 – 14.39 | 0.37

Constant | -3.53 | .000 | 0.03

Note: The other parameters (IES >9, SILGer12, and birth duration >12hrs) did not contribute to the model.

Table 8: correlations (Pearson’s r) – EPDS-items (week 1) with IES >9 (week 3)

Item No. | Item Description | Correlation (r)

01 | I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things | 0.44***

02 | I have looked forward with enjoyment to things | 0.52***

03 | I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong | 0.47***

04 | I have been anxious or worried for no good reason | 0.44***

05 | I have felt scared or panicky for no good reason | 0.58***

06 | Things have been getting to me | 0.41***

07 | I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping | 0.52***

08 | I have felt sad or miserable | 0.64***

09 | I have been so unhappy that I have been crying | 0.53***

10 | The thought of harming myself has occurred to me | 0.34***

Note:

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Table 9: Predictive Validity of Risk Assessments at Week 1 for acute stress reaction (trauma) and depression at week 3 (n = 209)

Type of Risk (Week 1) | Total N (%) | No Symptoms N (%) | Trauma Only N (%) | Depression Only N (%) | Trauma & Depression N (%)

No Risk | 62 (29.7%) | 60 (96.8%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%)

Risk for Trauma | 58 (27.8%) | 38 (65.5%) | 19 (34.5%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%)

Risk for Depression | 26 (12.4%) | 19 (73.1%) | 2 (7.1%) | 4 (14.3%) | 1 (3.6%)

Risk for Trauma & Depression | 63 (30.1%) | 30 (47.6%) | 10 (15.2%) | 6 (9.1%) | 17 (25.8%)

Total | 209 (100%) | 147 (70.3%) | 32 (15.3%) | 12 (5.7%) | 18 (8.6%)

Notes:

• Risk screening tools at week 1 included: SILGer12 ≤42, IES items 10 & 11, EPDS items 03 & 07, and team-rated BBCI-27.

• Two subjects initially screened as “No Risk” in week 1 later showed symptoms (one with trauma, one with depression).

• One subject identified at week 1 as at risk for trauma did not present with acute stress but with depressive symptoms at week 3.

• Two subjects identified at risk for depression (week 1) did not present with depression, but with acute stress at week 3, and one of these (correctly predicted as at risk for depression) presented, in addition, with symptoms of acute stress, not predicted by our screening.

Discussion and conclusion

A problematic postpartum well-being three weeks after delivery has to be considered a time point where women might run an elevated risk to develop clinically relevant depression or posttraumatic symptomatology. Therefore, it is crucial to detect those women at three weeks postpartum running such a risk. The combination of SILGer12 with 5 additional items (BBCI 27, IES 10 & 11, EPDS 03 & 07), applied in the first days after delivery (2–5th day), detects women in need of treatment at week 3, presenting with postpartum depression and/or with acute stress reactions postpartum with a sensitivity of 91.9%. As both, depression and posttraumatic stress, are associated with birth experience, screening assessment at day 2–5 begins with the SILGer12, complemented by 5 key items out of the team support spectrum, the impact-of-event spectrum and the depression spectrum. If the SILGer12-sum-score is 42, or lower, or if any of the 5 key items is on the cut-off-level, or beyond, this screening instrument is to be considered positive, identifying at-risk-women for either depression or acute stress reactions at three weeks postpartum. A positive SILGer12-score or one positive item out of two IES-items indicates an elevated risk for acute stress reaction at week 3 postpartum, and one positive item out of the team support item and the two EPDS-items indicates an elevated risk for postpartum depression at week 3 postpartum.

STRENGTH AND WEAKNESSES OF THIS STUDY

This sample of 209 participants yielded an almost complete data set, including birth parameters, birth experience (SIL-Ger12, week 1), perceived team support and measures of postpartum depression and acute stress reaction at both week 1 and week 3 following delivery. This comprehensive dataset enabled a thorough analysis and supported a robust interpretation of the findings.

A major strength of the tool lies in its framing: women are primarily asked about how they experienced what they went through, rather than being questioned directly about psychopathology. From a clinical perspective, this may contribute substantially to participant compliance—an aspect we regard as a strength of our approach.

However, the sample size of 209 may limit the clinical generalizability of the proposed screening tool, and replication studies with larger samples are recommended. Additionally, it remains unclear whether the fact that the data were collected nearly 30 years ago affects the current relevance of the findings. Changes in obstetric practices, societal norms, and healthcare systems over recent decades may influence psychological outcomes following childbirth and their processing in the early postpartum period.

It is also noteworthy that applying this screening approach—here referred to as the Swiss Postpartum Screening Tool (SPST)—would require reassessment at week 3 in 71.3% of postpartum women, predominantly using a single instrument (either the IES or the EPDS). Approximately one-third of women (31.6%) would require follow-up assessment with both instruments. The willingness of participants to complete an additional 10 to 25 items at week 3 remains uncertain. To enhance compliance—particularly among likely false positives—a future two-step screening strategy may prove advantageous. Such an approach could involve an initial brief assessment to determine the need for full-scale instrument completion.

CONCLUSION

The Swiss Postpartum Screening Tool (SPST) introduced in this study appears promising for the early identification of women at risk of postpartum psychological distress, thereby enabling timely intervention within three weeks after childbirth. Further studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to detect the small number of cases (n = 5) that remained undetected in the current approach. Moreover, future research should investigate the clinical trajectories of women identified as at risk at week 3, with and without intervention, at later postpartum stages—such as at three months. Another crucial area of investigation involves the development of abbreviated versions of the EPDS and IES, which retain adequate diagnostic utility for assessing acute stress and depression at week 3 based on risk identified in week 1.

References

1. Oates M. Deaths from suicide and other psychiatric causes. In Lewis G, Drife J: Why Mothers Die (2000-2002). The sixth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Death in the United Kingdom, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. London, 2004; S. 152-173. www.rcog.org.uk

2. Wisner KL, Sit DK, McShea MC, et al. Onset Timing, Thoughts of Self-harm, and Diagnoses in Postpartum Women with Screen-Positive Depression Findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(5):490-498. doi:10.1001/ jamapsychiatry.2013.87.

3. Thornton C, Schmied V, Dennis C-L, Barnett B, Dahlen HG. Maternal deaths in NSW (2000-2006) from nonmedical causes (suicide and trauma) in the first year following birth. Biomed Res Int. 2013:623743.

4. Ertan D, Hingray C, Burlacu E, Sterlé A, El-Hage W. Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth. BMC Psychiatry (2021) 21:155; https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03158-6

5. Bergant A, Nguyen T, Moser R, Ulmer H. Prävalenz depressiver Störungen im frühen Wochenbett. [prevalence of depressive mood in the early postpartum time] Gynäkol Geburtshilfliche Rundsch 1998; 38:232–237. https://doi.org/10.1159/000022270

6. Czarnocka J, Slade P. Prevalence and predictors of post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth. Br J Clin Psychol 2000;39: 35-51.

7. Creedy DK, Shochet IM, Horsfall J. Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms and contributing factors. Birth 2000;27(2): 104-111.

8. Ayers S, Bond R, Bertullies S, Wijma K. The aetiology of post-traumatic stress following childbirth: a meta-analysis and theoretical framework. Psychol Med, 2016 Apr;46(6):1121-34. doi: 10.1017/S0033 291715002706.

9. Guerber S, Bielinski D, Lemola S, Jaussi C, von Wyl A, Surbek D, Grob A, Stadlmayr W. Maternal mental health in the first three weeks postpartum. The impact of caregiver support and the subjective experience of childbirth: a longitudinal path model. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics. 2012, 33(4): 176-84.

10. Stadlmayr W, Lemola S, Amsler F, Stein S, Cignacco E, Surbek D, Bitzer J. Depressive Verstimmungen und/ oder traumatogene Reaktionen 3 Wochen postpartum: Entwicklung eines postpartalen Screenings (3. & 4. Tag pp) mittels SIL-Ger_12 [Depressive mood and/ or traumatic reactions 3 week postpartum: development of postpartum screening (3 & 4 days postpartum) by means of SILGer12] (Poster 07.11). Z Geburtsh Neonatol 2005;209: 122.

11. Stadlmayr W. Cignacco E, Surbek D, Büchi S. Screening-Instrumente zur Erfassung von Befindlichkeitsstörungen nach der Geburt. [Screening tools for the assessment of psychological disturbances after birth]. Die Hebamme 2009; 22: 13-19.

12. Kumar RC. “Anybody’s child”: severe disorders of mother-to-infant bonding. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171(2):175-181. doi:10.1192/bjp.171.2.175.

13. Righetti-Veltema M, Conne-Perreard E, Bousquet A, Manzano J. Risk factors and predictive signs of postpartum depression. J Affect Disord 1998;49(3):167-80

14. Olde E, van der Hart O, Kleber R, van Son M. Posttraumatic stress following childbirth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review 2006; 26: 1-26.

15. Manzano J, Righetti- Veltema M, Conne- Perréard E (1996) Le Syndrome de Dépression du Prépartum: Un Nouveau Concept. [The syndrome of prepartum depression: a new concept] In: Manzano J (ed) Les relations précoces parents- enfants et leurs troubles: VIe Symposium de Genève de psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent (11.- 13.5.1995), Medicine et Hygiène, p. 131-142.

16. Andersen LB, Melvaer LB, Videbech P, Lamont RF, Joergensen JS. Risk factors for developing post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012 Nov;91(11):1261-72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-041 2.2012.01476.x.

17. Stadlmayr W, Bitzer J, Hösli I, Amsler F, Leupold J, Schwendke- Kliem A, Simoni H, Bürgin D. Birth as a Multidimensional Experience: Comparison of the English- and German- Language Version of Salmon’s Item List, Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 2001;22(4):205-14.

18. Schlumpf-van Waardenburg B, Wälchli E. Wie erleben Eltern die Geburt? Ein Scoping Review zu Anwendung und Nutzen der Salmon’s Item List-German Language Version. [How do parents experience birth? A scoping review to evaluate the use and benefit of Salmon’s Item List German Language Version] 2024 unveröffentlichte Bachelorarbeit [unpublished Bachelor Thesis], Berner Fachhochschule Gesundheit, Bachelor-Studiengang Hebamme.

19. Salmon P, Miller, R. Women’s anticipation and experience of childbirth: the independence of fulfilment, unpleasantness and pain. British Journal of medical Psychology 1990;63(3):255-259.

20. Salmon P, Drew NC. Multidimensional Assessment of Women’s Experience of Childbirth: Relationship to Obstetric Procedure, Antenatal Preparation and Obstetric History. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 1992;36(4):317-327.

21. Stadlmayr W, Amsler F, Lemola S, Stein S, Alt M, Bürgin D, Surbek D, Bitzer J. Memory of childbirth in the second year: The long-term effect of a negative birth experience and its modulation by the perceived intranatal relationship with caregivers. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 2006;27(4):211-224.

22. Cox, J.L., Holden, J.M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-Item Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 782—786.

23. Murray D, Cox J: Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EPDS). J Reprod Infant Psychol 1990; 8: 99-107.

24. Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W (1979) Impact of Event Scale: A Measure of Subjective Stress. Psychosomatic Medicine 41 (3):209-218.

25. Zilberg NJ, Weiss DS, Horowitz MJ. Imapct of event scale: a cross validation study and some empirical evidence supporting a conceptual model of stress response syndromes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1982;50:407-414.

26. Weiss D, Marmar C. The impact-of-event scale—revised. In: Wilson J, Keane T, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York, London: Guilford Press; 1997. p. 399–411

27. Stadlmayr W, Bitzer J, Amsler F, Simoni H, Alder J, Surbek D, Bürgin D. Acute stress reactions in the first 3 weeks postpartum: A study of 219 parturients. Europ. J. Obstet. Gynaecol & Reprod. Biol 2007; 135:65-72.

28. Sundin EC, Horowitz M. Horowitz’s Impact of Event Scale evaluation of 20 years of use. Psychosomatic Medicine 2003;65: 870-876.