JAK-STAT Inhibitors: Transforming Autoimmune Disease Treatment

JAK-STAT Inhibitors: A Game Changer, from Rheumatology to Gastroenterology

Shivam Kalra, MD¹*, Rishi Chowdhary²*, Eva Kalra, MD¹, Sonam Dhall, MBBS³, Gurmanleen Singh Sohi, MBBS⁴, Anmol Singh, MD⁵, Ashita Rukmini Vuthaluru, MBBS, MD6; Manjeet Kumar Goyal, MD7

- Department of Internal Medicine, Trident Medical Center, North Charleston, SC, USA

- Department of Medicine, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH, USA

- Department of Medicine, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab, India

- Department of Medicine, Government Medical College, Patiala, Punjab, India

- Department of Internal Medicine, John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County, Chicago, IL, USA

- Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New delhi, India

- Department of Internal Medicine, Cleveland Clinic Akron General, Akron, OH, USA

†Corr. Author: [email protected]

Corresponding Author: [email protected]

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 September 2025

CITATION: Kalra, S., et al., 2025. JAK-STAT Inhibitors: A Game Changer, from Rheumatology to Gastroenterology. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(9). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6935

COPYRIGHT: This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6935

ISSN: 2375-1924

Abstract

Autoimmune diseases represent a growing global health concern, with a rising incidence and prevalence across the globe, and are expected to exponentially rise through 2050. This increase is attributed to factors such as urbanization, lifestyle changes, and improved healthcare access. Historically, the management of autoimmune and immune-mediated diseases has revolved around broad immunosuppression, primarily relying on corticosteroids and other disease-modifying agents. These have limitations such as non-specific immunosuppression, increased risk of infection, and end-organ damage. In subsequent years, the therapeutic armamentarium expanded to include biologic agents that selectively target individual pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha inhibitors and anti-integrin or anti-interleukin-12/23 therapies. Although biologics have improved disease outcomes and enabled more targeted intervention, their use is constrained by factors such as immunogenicity, the need for parenteral administration, and a persistent risk of adverse effects, including serious infections and malignancy. These limitations have underscored the need for novel therapeutic modalities with improved efficacy, safety, and patient convenience. The advent of Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) inhibitors has transformed the therapeutic landscape of immune-mediated diseases. Tofacitinib, upadacitinib, and filgotinib are orally administered small molecules that inhibit intracellular signaling of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which modulate several pathways simultaneously. In recent years, a therapeutic paradigm shift has emerged in the field of gastroenterology, with JAK inhibitors being increasingly utilized for the management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). These have demonstrated efficacy in both induction and maintenance of remission, including among patients refractory to anti-TNF and other biologic therapies. This article will focus on the evolving role and paradigm shift in the use of JAK-STAT inhibitors from rheumatology to gastroenterology.

Keywords

- JAK-STAT inhibitors

- autoimmune diseases

- rheumatology

- gastroenterology

- inflammatory bowel disease

Introduction

The global incidence and burden of immune-mediated diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and psoriasis, are rising, with projections indicating continued growth through 2050. With rising urbanization, improvement in lifestyle, and accessibility to quality healthcare resources, these conditions, once considered to be prevalent in the industrialized world, have shown an increase in prevalence worldwide. Historically, management of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatological and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) has relied on suppression of the immune system primarily by corticosteroids. Over the past two decades, conventional immunosuppressants (e.g., methotrexate, azathioprine) and biologic agents targeting individual cytokines (e.g., TNF inhibitors, anti-integrin, anti-IL-12/23 therapies) have been widely used. However, these agents have shown limited efficacy with various limitations such as immunogenicity, parenteral administration, and significant adverse effect profiles, including infection, malignancy, and organ toxicity, etc have restricted their use.

The advent of Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) inhibitors marked a paradigm shift in the treatment of these disorders. JAK-STAT inhibitors, such as tofacitinib, upadacitinib, and filgotinib, are orally administered small molecules that inhibit intracellular signaling of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines. Unlike biologics that block individual cytokines, JAK inhibitors can modulate several cytokine pathways simultaneously. Tofacitinib exhibits broader JAK inhibition, while upadacitinib and filgotinib are more selective for JAK1. Their low immunogenicity, oral administration, and rapid onset of action further distinguish them from traditional biologics (Table 1).

Initially developed for rheumatological conditions, JAK-STAT inhibitors have revolutionized IBD management and achievement of endoscopic, histological, and clinical remission. This review outlines the paradigm shift in the therapeutic application of JAK-STAT inhibitors from their initial use in rheumatologic diseases to their emerging role in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease by summarizing the current evidence supporting their efficacy in gastroenterological practice.

Mechanism and Pathophysiology

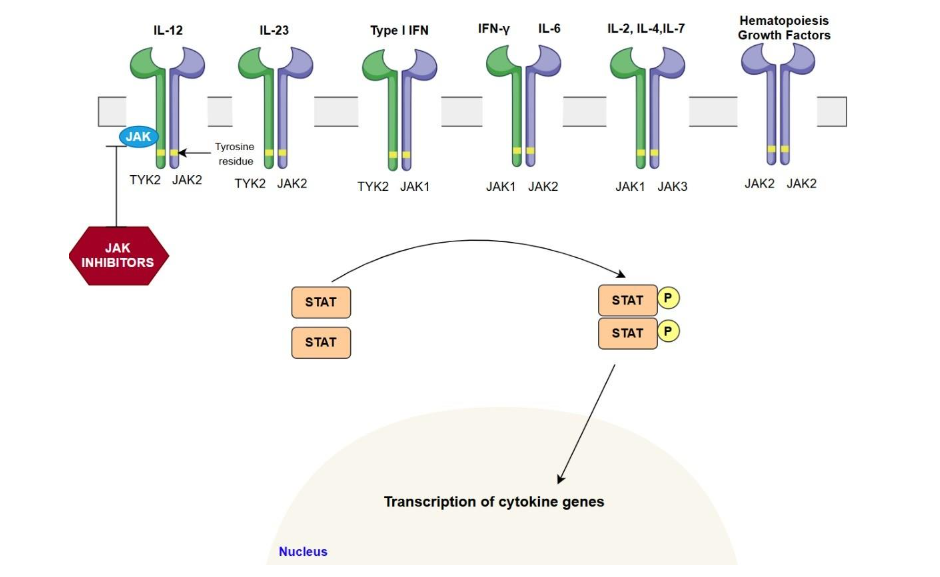

The JAK-STAT signaling pathway involves a membrane-bound cytokine receptor linked to Janus kinases (JAKs), which are intracellular tyrosine kinases, and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs). The JAK family includes four members: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2. Upon cytokine binding, JAKs located on the cytoplasmic portion of the receptor undergo autophosphorylation and transphosphorylation. This phosphorylation cascade activates STAT proteins, which then dimerize and translocate to the nucleus to initiate transcription of genes involved in inflammation. The pathway is tightly regulated at multiple levels, including by cellular phosphatases that dephosphorylate receptors and STATs to attenuate the signal.

In ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), this pathway mediates the effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, and IFN-γ, driving chronic mucosal inflammation, epithelial barrier dysfunction, and immune cell recruitment. The IL-6/JAK1/STAT3 axis is particularly important in UC, while the IL-12/IL-23 axis (signaling through JAK2 and TYK2) is more prominent in CD. In rheumatological diseases, JAK-STAT signaling underlies the activation and survival of autoreactive T and B cells, production of inflammatory mediators, and tissue destruction. Genetic studies have identified polymorphisms in JAK and STAT genes that confer susceptibility to IBD and rheumatological diseases. The selectivity of JAK inhibitors for particular isoforms (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, TYK2) is a key factor influencing both efficacy and toxicity. First-generation therapeutic drugs, like tofacitinib, inhibit a broader range of JAK isoforms, whereas second-generation drugs such as upadacitinib and filgotinib exhibit more selectivity.

History and Role of JAK-STAT Inhibitors in Rheumatology

JAK-STAT inhibitors have been recognized as efficacious treatments for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondyloarthritis. It has been well established through clinical trials and meta-analyses that JAK inhibitors are superior to placebo and are at least non-inferior to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) regarding key clinical endpoints, including ACR20/50/70 responses (Note: The American College of Rheumatology defines ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 response criteria as at least 20%, 50%, and 70% improvement, respectively). A meta-analysis of 39 studies with 16,894 individuals evaluated six JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib, baricitinib, upadacitinib, filgotinib, peficitinib, and decernotinib) and determined that all drugs exhibited superior ACR responses relative to placebo. Decernotinib 300 mg exhibited the most significant ACR50 response, whereas upadacitinib 15 mg presented the greatest likelihood of attaining remission and minimal disease activity in DMARD-naive patients. Indirect comparisons indicate that upadacitinib may exhibit statistically superior response rates relative to tofacitinib and baricitinib.

Combination therapy with methotrexate (MTX) augments the effectiveness of JAK inhibitors. This yields higher ACR response rates and greater attainment of low disease activity/remission compared to JAK monotherapy. Phase 2 and 3 trials have demonstrated the efficacy of tofacitinib, upadacitinib, and filgotinib in PsA and axSpA, with outcomes comparable to biologic DMARDs. Upadacitinib, notably, achieved high ACR20/50/70 responses in the SELECT-PsA trials and has emerged as a preferred oral option for PsA. It is now FDA-approved for active PsA, whereas filgotinib and baricitinib are not indicated for PsA as of 2025. In axial spondyloarthritis, upadacitinib became the first JAK inhibitor approved for ankylosing spondylitis (radiographic axSpA) and non-radiographic axSpA, based on the SELECT-AXIS trials.

Transition to Gastroenterology

Their success in rheumatology, marked by swift onset of action, oral delivery, ability to simultaneously target multiple cytokines, and effectiveness in patients unresponsive to traditional and biologic DMARDs, led to discovery in other immune-mediated pathologies with comparable cytokine patterns. Pathogenesis of IBD (UC and CD) also shares the JAK-STAT pathway. As a result, JAK inhibitors such as tofacitinib, upadacitinib, and filgotinib were evaluated in clinical trials for IBD, demonstrating significant efficacy in inducing and maintaining remission, especially in patients with moderate-to-severe disease who had failed biologic therapies. This transition from rheumatology to gastroenterology demonstrates a paradigm shift in the treatment of autoimmune chronic inflammatory gastrointestinal indications.

Clinical Trials and Comparative Efficacy in IBD

The success of JAK inhibitors in rheumatology paved the way for research in IBD, where the need for oral, non-immunogenic therapies with rapid onset was unmet.

Ulcerative Colitis: Tofacitinib was the first JAK inhibitor approved for moderate-to-severe UC, based on the pivotal phase III OCTAVE Induction and Maintenance trials (Table 2). By week 8 of induction, ~18% of tofacitinib-treated UC patients achieved remission, compared to ~8% on placebo; at 52 weeks of maintenance, remission was ~34% on tofacitinib versus ~11% on placebo. The TACOS trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients hospitalized with acute severe ulcerative colitis, demonstrating that adding tofacitinib (10 mg three times daily for 7 days) to intravenous corticosteroids significantly improved the day-7 response (83% vs 60% on steroids alone) and reduced the need for rescue therapy or colectomy.

Upadacitinib was evaluated in the U-ACHIEVE and U-ACCOMPLISH Phase 3 trials for UC, showing high rates of clinical and endoscopic remission in both biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients. Induction therapy with upadacitinib 45 mg led to clinical remission at 8 weeks in ~26-33% of UC patients (depending on prior biologic exposure), versus ~5-14% with placebo. Endoscopic improvement was also significantly higher (e.g., ~41% on upadacitinib vs ~7% on placebo in one induction study).

Filgotinib 200 mg induced clinical remission in ~26% of UC patients by week 10 (placebo ~15%) and maintained remission in ~37% at week 54 (placebo ~11%). Notably, Filgotinib’s safety profile in UC was favorable, with lower rates of serious infections and herpes zoster compared to tofacitinib, reflecting its JAK1-selectivity. Filgotinib, brand name Jyseleca, received approval for UC in Europe and Japan in late 2021, but it is not approved in the United States due to FDA concerns about the 200 mg dose and male reproductive toxicity.

| JAK Inhibitor | Pivotal Trials (Phase) | Outcomes | Approval Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tofacitinib | OCTAVE 1&2 (Phase III induction); OCTAVE Sustain (maintenance) | Induction remission: 18.5% vs 8.2% (OCTAVE1); 16.6% vs 3.6% (OCTAVE2). Maintenance remission (52 wk): 34.3% (5 mg BID) & 40.6% (10mg BID) vs 11.1% | Approved (FDA 2018) for moderate-severe UC; EMA approved. |

| Upadacitinib | U-ACHIEVE UC1 & UC2 (Phase III induction); U-ACHIEVE UC3 (maintenance) | Induction remission (wk8): 26-34% on 45mg QD vs 4-5% on placebo. Maintenance (wk52): 42% (15 mg) & 52% (30 mg) vs 12% on placebo | Approved (FDA 2022, EMA 2023) for refractory moderate-severe UC. |

| Filgotinib | SELECTION trial (Phase IIb/III: induction wk10, maintenance wk58) | Induction (wk10): remission ~20-30% vs ~10% placebo. Maintenance: higher remission at wk58 with 200 mg | Approved (EMA 2021) for moderate severe UC refractory to biologics |

| Peficitinib | Phase IIb (8 wk induction) | Failed to show dose-response trend; no significant induction of remission. | Development halted (no approval). |

| Others (e.g., TD-1473) | Phase II studies | Early trials did not meet endpoints (izencitinib/TD-1473 failed in a 12-wk dose-ranging study). | Not approved. |

Crohn’s Disease

The advancement of JAK inhibitors in Crohn’s disease has been complex. Tofacitinib failed to achieve primary endpoints in phase II trials for Crohn’s disease, resulting in the cessation of its development for this application. Conversely, filgotinib and upadacitinib have exhibited success in phase II and III trials. Upadacitinib, however, achieved positive results in Phase 3 Crohn’s studies and is now an approved therapy (in 2023, it became the first oral treatment for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease in the US, Europe, and other regions). In two induction trials (U-EXCEED and U-EXCEL), upadacitinib 45 mg once daily produced clinical remission by 12 weeks in ~40-49% of Crohn’s patients, versus 21-29% on placebo (remission defined by Crohn’s Disease Activity Index). Endoscopic response at 12 weeks was achieved in ~45% of upadacitinib-treated patients compared to ~13% on placebo. In the maintenance trial (U-ENDURE), responders were re-randomized to upadacitinib 15 mg or 30 mg daily vs placebo; after 52 weeks, clinical remission was maintained in ~36-47% on upadacitinib (dose-dependent) vs ~15% on placebo. Filgotinib, in contrast, showed promise in a Phase 2 Crohn’s trial (FITZROY) but did not meet its co-primary endpoints in the Phase 3 DIVERSITY program. The two induction cohorts of DIVERSITY failed to demonstrate a significant benefit of filgotinib over placebo at week 10 (no difference in clinical remission or endoscopic response). While the maintenance phase of DIVERSITY indicated filgotinib 200 mg could sustain remission (e.g., 44% on filgotinib vs 26% on placebo at week 58 achieved clinical remission; endoscopic response 30% vs 9%). Thus, Filgotinib was halted.

| JAK Inhibitor | Trial (Phase) | Outcomes | Status/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tofacitinib | Phase II induction and Maintenance | Failed to meet primary endpoint (CDAI remission at wk8); no significant clinical benefit. | Not approved for Crohn’s. |

| Filgotinib | FITZROY (Phase II induction 10 wk) | Remission at wk10: 47% on 200 mg vs 23% on placebo (p=0.0077) | Phase III studies conducted; not approved yet. |

| Upadacitinib | U-EXCEED & U-EXCEL (induction); U-ENDURE (maintenance) | Week-52 CDAI remission: 37% (15 mg) and 48% (30 mg) vs 15% placebo; superior endoscopic remission | FDA-approved (2023) for moderate severe. |

| Peficitinib | Phase II | Data limited; no signals of efficacy published. | No further development in CD. |

| Others (TD-1473, etc.) | Early-phase | TD-1473 failed to meet endpoints; other gut-selectives discontinued. | Not approved. |

Other GI Disorders

Beyond IBD, the JAK-STAT pathway is implicated in eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs) such as eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), gastritis/enteritis, and colitis. These conditions are driven by type-2 cytokines (IL-5, IL-13) that signal via JAK-STAT. To date, no JAK inhibitor is specifically approved for EGIDs, but there are compelling case reports. For example, a patient with long-standing eosinophilic esophagitis, gastritis, and enteritis, with eosinophilia, achieved improvement on tofacitinib 5 mg BID: after 6 months, both endoscopically and clinically. Similarly, in eosinophilic colitis, a small case series (four adults) reported complete clinical and histologic remission using JAK inhibitors: two patients on baricitinib (4 mg QD) and two on upadacitinib (15 mg QD) all improved within weeks.

| Condition | JAK Inhibitor(s) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Eosinophilic esophagitis/gastroenteritis | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Case of refractory EGIDs (esophagitis, stomach, duodenum): symptoms resolved, endoscopic and histologic eosinophilia normalized after 6 months |

| Eosinophilic colitis | Upadacitinib 15 mg QD; Baricitinib 4 mg QD | 4 patients: rapid improvement; colon biopsies showed remission |

| Eosinophilic gastritis/duodenitis | Upadacitinib 15 mg QD (+ budesonide) | Case: symptom relief and histologic remission |

| Other EGIDs | No controlled trials; scattered case reports suggest benefit |

Real-World Effectiveness and Patient-Reported Outcomes

Real-world evidence substantiates the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in both gastroenterology and rheumatology, albeit with certain variations. Multicenter trials and meta-analyses in IBD indicate that upadacitinib and filgotinib are efficacious in inducing and maintaining remission in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, even in patients with previous biologic failure. Clinical remission rates for upadacitinib in real-world inflammatory bowel disease cohorts vary between 25% and 55%, with endoscopic remission rates aligning with those seen in randomized controlled trials, but marginally lower due to the more refractory characteristics of real-world populations. The oral administration, rapid onset of action, and lack of immunogenicity are valued in both fields, but may be particularly advantageous in IBD, where rapid symptom control and avoidance of parenteral therapies are often desired.

Safety Outcomes and Comparative Risks

The concerns for the safety profile of JAK inhibitors persist. JAK inhibitors are linked to an increased incidence of infections (particularly herpes zoster), venous thromboembolism (VTE), and, in some groups, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and malignancies. The ORAL Surveillance study in rheumatoid arthritis indicated that tofacitinib was statistically inferior to TNFi regarding the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events and malignancies in patients over 50 years old with at least one cardiovascular risk factor. Observational studies and meta-analyses demonstrate an elevated risk of herpes zoster and a moderately heightened risk of malignancy in patients treated with JAK inhibitors compared to TNFi, with the absolute risk being most significant in older adults and individuals with additional risk factors.

In IBD, the risk profile is more favorable. Risk of severe infection and malignancy is not markedly elevated in comparison to TNFi, and the incidence of MACE is low, potentially attributable to the younger demographic and reduced comorbidity burden of IBD patients. The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) guideline indicates that JAK inhibitors may present an elevated cancer risk compared to TNFi in older persons with cardiovascular risk factors, and advises cautious use in patients with a history of cancer. The risk of herpes zoster is elevated with JAK inhibitors in inflammatory bowel disease; however, the absolute incidence remains lower than in rheumatoid arthritis.

Regulatory Evolution and Therapeutic Positioning

The regulatory status and approved indications of JAK-STAT inhibitors are evolving due to the accumulation of clinical trial data and post-marketing safety signals. In rheumatology, JAK inhibitors are generally approved for use after failure of, or intolerance to, conventional synthetic DMARDs, and may be used before or after biologic agents, depending on regional guidelines and payer policies. The safety concerns identified in the rheumatology population, particularly the increased risk of MACE and malignancy in older adults with cardiovascular risk factors, have led to boxed warnings.

The FDA label for JAK inhibitors in ulcerative colitis stipulates their usage exclusively for patients who have previously failed or exhibited sensitivity to TNF antagonists, so designating them as second-line or subsequent therapy. The AGA guideline emphasizes individualized decision-making, taking into account patient preferences, comorbidities, and risk factors for adverse events. In Europe, the European Medicines Agency allows for cautious first-line use in certain high-risk patients but generally mirrors the US approach in restricting use to those who have failed other advanced therapies.

Mechanistic Insights and Next-Generation Agents

Next-generation JAK-STAT inhibitors, especially those aimed at TYK2 and gut-selective drugs, are being developed to overcome the safety and effectiveness constraints of previous JAK inhibitors. TYK2 inhibitors, including deucravacitinib, have significant selectivity and an acceptable safety profile, with early-phase trials indicating efficacy in psoriasis and encouraging outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatologic disorders. Dual JAK1/TYK2 inhibitors and gut-selective drugs aim to optimize efficacy while reducing systemic exposure and off-target effects. These advancements are expected to boost therapy alternatives for IBD and rheumatology.

Limitations and Uncertainties in Current Evidence

Despite the robust evidence base, significant limitations and uncertainties remain, particularly regarding optimal sequencing of therapies and patient selection. Most pivotal trials have relatively short follow-up and highly selected populations, limiting generalizability to real-world practice. There is a paucity of direct head-to-head trials comparing different JAK-STAT inhibitors or comparing JAK inhibitors to other advanced therapies in either IBD or rheumatology. The lack of proven predictive biomarkers that guide patient selection hinders clinical decision-making. The long-term safety profile is not completely determined, particularly for the newer, more selective JAK1 and TYK2 inhibitors.

Conclusion

JAK-STAT inhibitors have transformed the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory disorders, resulting in a significant shift in clinical and scientific emphasis from rheumatology to gastroenterology. The robust effectiveness of JAK inhibitors in both rheumatoid arthritis and gastroenterology, especially IBD, particularly UC, is supported by comprehensive clinical trial and real-world evidence. The safety profile, although generally acceptable, requires meticulous patient selection and risk stratification, particularly in elderly individuals and those with cardiovascular risk factors. The regulatory environment demonstrates these apprehensions, exhibiting more stringent indications in IBD than in rheumatology. Next-generation medicines, such as TYK2 and gut-selective inhibitors, promise to enhance the benefit-risk balance and broaden therapy options. Further prospective research, long-term surveillance, and personalized, patient-centered care will be essential to fully realize the potential of JAK-STAT inhibitors in both rheumatology and gastroenterology.

Declarations:

- Competing interests: All authors did not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

- Funding: No funding was obtained for this study.

- Ethics approval: No ethical approval is required.

- Consent to participate: Patient consent was not required for this study.

- Consent to publish: Patient consent was not required for this study.

- Data and/or Code availability: All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper.

- Author contributions: MG, ARV: Study concept and supervision. SK, RC, and EK: Literature review and drafting of the manuscript. SD, GS, and AS: Critical appraisal of selected literature and editing. SK, RC, ARV and MG: Final review, interpretation of content, and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed meaningfully to the development of this review and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments:

HCA Healthcare disclaimer: This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare-affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.

References:

- Hao C, Ting L, Feng G, Jing X, Ming H, Yang L, et al. Global incidence trends of autoimmune diseases from 1990 to 2021 and projections to 2050: A systemic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Autoimmun Rev. 2024 Sep 2; 103621.

- Hracs L, Windsor JW, Gorospe J, Cummings M, Coward S, Buie MJ, et al. Global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease across epidemiologic stages. Nature. 2025 Jun; 642(8067):458-66.

- Fansiwala K, Sauk JS. Small molecules, big results: How JAK inhibitors have transformed the treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2025 Feb; 70(2):469-77.

- Caballero-Mateos AM, Cañadas-de la Fuente GA. Game changer: How Janus kinase inhibitors are reshaping the landscape of ulcerative colitis management. World J Gastroenterol. 2024 Sep 21; 30(35):3942-53.

- Herrera-de Guise C, Serra-Ruiz X, Lastiri E, Borruel N. JAK inhibitors: A new dawn for oral therapies in inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023; 10:1089099.

- Benucci M, Bernardini P, Coccia C, De Luca R, Levani J, Economou A, et al. JAK inhibitors and autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2023 Apr; 22(4):103276.

- Cordes F, Foell D, Ding JN, Varga G, Bettenworth D. Differential regulation of JAK/STAT signaling in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2020 Jul 28; 26(28):4055-75.

- Taylor PC, Choy E, Baraliakos X, Szekanecz Z, Xavier RM, Isaacs JD, et al. Differential properties of Janus kinase inhibitors in the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2024 Feb 1; 63(2):298-308.

- Chen Z, Jiang P, Su D, Zhao Y, Zhang M. Therapeutic inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2024 Oct; 79:1-15.

- Nielsen OH, Boye TL, Gubatan J, Chakravarti D, Jaquith JB, LaCasse EC. Selective JAK1 inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2023 May; 245:108402.

- Almoallim HM, Omair MA, Ahmed SA, Vidyasagar K, Sawaf B, Yassin MA. Comparative efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in the management of rheumatoid arthritis: A network meta-analysis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2025 Jan 28; 18(2):178.

- Lee YH, Song GG. Relative remission and low disease activity rates of tofacitinib, baricitinib, upadacitinib, and filgotinib versus methotrexate in patients with disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-naive rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacology. 2023; 108(6):589-98.

- Genovese MC, Kalunian K, Gottenberg JE, Mozaffarian N, Bartok B, Matzkies F, et al. Effect of filgotinib vs placebo on clinical response in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis refractory to disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy: The FINCH 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019 Jul 23; 322(4):315-25.

- Liu L, Yan YD, Shi FH, Lin HW, Gu ZC, Li J. Comparative efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors as monotherapy and in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2022; 13:977265.

- Wang F, Tang X, Zhu M, Mao H, Wan H, Luo F. Efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022 Jul 30; 11(15):4459.

- Tóth L, Juhász MF, Szabó L, Abada A, Kiss F, Hegyi P, et al. Janus kinase inhibitors improve disease activity and patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 24,135 patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan 23; 23(3):1246.

- Vallez-Valero L, Gasó-Gago I, Marcos-Fendian Á, Garrido-Alejos G, Riera-Magallón A, Plaza Diaz A, et al. Are all JAK inhibitors for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis equivalent? An adjusted indirect comparison of the efficacy of tofacitinib, baricitinib, upadacitinib, and filgotinib. Clin Rheumatol. 2023 Dec; 42(12):3225-35.

- Lee EB, Fleischmann R, Hall S, Wilkinson B, Bradley JD, Gruben D, et al. Tofacitinib versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jun 19; 370(25):2377-86.

- Klavdianou K, Papagoras C, Baraliakos X. JAK inhibitors for the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2023 Jun 30; 34(2):129-38.

- McInnes IB, Anderson JK, Magrey M, Merola JF, Liu Y, Kishimoto M, et al. Trial of upadacitinib and adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2021 Mar 31; 384(13):1227-39.

- Deodhar A, van der Bosch F, Poddubnyy D, Maksymowych WP, van der Heijde D, Kim TH, et al. Upadacitinib for the treatment of active non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (SELECT-AXIS 2): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022 Jul 30; 400(10349):369-79.

- Singh A, Goyal MK, Midha V, Mahajan R, Kaur K, Gupta YK, et al. Tofacitinib in acute severe ulcerative colitis (TACOS): A randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Jul 1; 119(7):1365-72.

- Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibition for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: New hope on the rise. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 Nov 15; 27(12):2023-30.

- Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, D Haens GR, Vermeire S, Schreiber S, et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017 May 4; 376(18):1723-36.

- Danese S, Vermeire S, Zhou W, Pangan AL, Siffledeen J, Greenbloom S, et al. Upadacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: Results from three phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, randomized trials. Lancet. 2022 Jun 4; 399(10341):2113-28.

- Vermeire S, Danese S, Zhou W, Pangan A, Greenbloom S, D Haens G, et al. OP23 efficacy and safety of upadacitinib as induction therapy in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: Results from phase 3 U-ACCOMPLISH study. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 May 27; 15(Suppl 1):S021-2.

- Feagan BG, Danese S, Loftus EV, Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Ritter T, et al. Filgotinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (SELECTION): A phase 2b/3 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2021 Jun 19; 397(10292):2372-84.

- Rogler G. Efficacy of JAK inhibitors in Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Aug 1; 14(Suppl 2):S746-54.

- Goyal MK. Comments on Enduring clinical remission in refractory celiac disease type II with tofacitinib: An open-label clinical study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Mar 1; 23(4):678-9.

- Loftus EV, Panés J, Lacerda AP, Peyrin-Biroulet L, D Haens G, Panaccione R, et al. Upadacitinib induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023 May 24; 388(21):1966-80.

- Farkas B, Bessissow T, Limdi JK, Sethi-Arora K, Kagramanova A, Knyazev O, et al. Real-world effectiveness and safety of selective JAK inhibitors in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: A retrospective, multicentre study. J Clin Med. 2024 Dec 20; 13(24):7804.

- Goyal MK, Kalra S, Rao A, Khubber M, Gupta A, Vuthaluru AR. Beyond the gut: Exploring neurological manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. Brain & Heart 2024, 2(4), 3486.

- Elford AT, Bishara M, Plevris N, Gros B, Constantine-Cooke N, Goodhand J, et al. Real-world effectiveness of upadacitinib in Crohn’s disease: A UK multicentre retrospective cohort study. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2024 Jul; 15(4):297-304.

- Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Petryka R, Kuehbacher T, Hebuterne X, Roblin X, et al. Clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease treated with filgotinib (the FITZROY study): Results from a phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Feb 1; 10(2):138-53.

- Solitano V, Vuyyuru SK, MacDonald JK, Zayadi A, Parker CE, Narula N, et al. Efficacy and safety of advanced oral small molecules for inflammatory bowel disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2023 Nov 24; 17(11):1800-16.

- Akiyama S, Shimizu H, Tamura A, Yokoyama K, Sakurai T, Kobayashi M, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of three Janus kinase inhibitors in ulcerative colitis: A real-world multicentre study in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025 Feb; 61(3):524-37.

- Li Y, Yao C, Xiong Q, Xie F, Luo L, Li T, et al. Network meta-analysis on efficacy and safety of different Janus kinase inhibitors for ulcerative colitis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2022 Jul; 47(7):851-9.

- Burmester GR, Mysler E, Taylor P, Hall S, Wick-Urban B, Garrison A, et al. Benefit risk analysis of upadacitinib versus adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and higher or lower risk of cardiovascular disease. RMD Open. 2025 Jun 3; 11(2):e005371.

- Yang H, An T, Zhao Y, Shi X, Wang B, Zhang Q. Cardiovascular safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2025 Dec; 57(1):2455536.

- Bieber T, Feist E, Irvine AD, Harigai M, Haladyj E, Ball S, et al. A review of safety outcomes from clinical trials of baricitinib in rheumatology, dermatology and COVID-19. Adv Ther. 2022; 39(11):4910-60.

- Fakhouri W, Wang X, de la Torre I, Nicolay C. A network meta-analysis to compare effectiveness of baricitinib and other treatments in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to methotrexate. J Health Econ Outcomes Res. 2020 Apr 10; 7(1):10-23.

- Zeng L, Feng S, Yao L, Wang B, Zhang G. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Adv Dermatol Allergol. 2023 Dec; 40(6):734-40.

- Genovese MC, Greenwald MW, Gutierrez-Ureña SR, Cardiel MH, Poiley JE, Zubrzycka-Sienkiewicz A, et al. Two-year safety and effectiveness of peficitinib in moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis: A phase IIb, open-label extension study. Rheumatol Ther. 2019 Dec; 6(4):503-20.

- Lee YH, Song GG. Comparative efficacy and safety of tofacitinib, baricitinib, upadacitinib, filgotinib and peficitinib as monotherapy for active rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020 Aug; 45(4):674-81.

- Gadina M, Schwartz DM, O’Shea JJ. Decernotinib: A next-generation jakinib. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Jan; 68(1):31-4.

- Zheng DY, Wang YN, Huang YH, Jiang M, Dai C. Effectiveness and safety of upadacitinib for inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCT and real-world observational studies. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024 Jan 5; 126:111229.

- Olivera PA, Lasa JS, Bonovas S, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases or other immune-mediated diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020 May; 158(6):1554-73.e12.

- Uchida T, Iwamoto N, Fukui S, Morimoto S, Aramaki T, Shomura F, et al. Comparison of risks of cancer, infection, and major adverse cardiovascular events associated with JAK inhibitor and TNF inhibitor treatment: A multicentre cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023 Oct 3; 62(10):3358-65.

- Cho Y, Yoon D, Khosrow-Khavar F, Song M, Kang EH, Kim JH, et al. Cardiovascular, cancer, and infection risks of Janus kinase inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis and ulcerative colitis: A nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med. 2025 Apr; 297(4):366-81.

- Misra DP, Pande G, Agarwal V. Cardiovascular risks associated with Janus kinase inhibitors: Peering outside the black box. Clin Rheumatol. 2023 Feb; 42(2):621-32.

- Szekanecz Z, Buch MH, Charles-Schoeman C, Galloway J, Karpouzas GA, Kristensen LE, et al. Efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: Update for the practising clinician. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2024 Feb; 20(2):101-15.

- Cohen S, Reddy V. Janus kinase inhibitors: Efficacy and safety. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2023 Nov 1; 35(6):429-34.

- Martinez-Molina C, Gich I, Diaz-Torné C, Park HS, Feliu A, Vidal S, et al. Patient-related factors influencing the effectiveness and safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: A real-world study. Sci Rep. 2024 Jan 2; 14(1):172.

- Bernardi F, Faggiani I, Parigi TL, Zilli A, Allocca M, Furfaro F, et al. JAK inhibitors and risk of cancer in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Cancers (Basel). 2025 May 28; 17(11):1795.

- Singh S, Loftus EV, Limketkai BN, Haydek JP, Agrawal M, Scott FI, et al. AGA living clinical practice guideline on pharmacological management of moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2024 Dec 1; 167(7):1307-43.

- Tanaka Y, Luo Y, O’Shea JJ, Nakayamada S. Janus kinase-targeting therapies in rheumatology: A mechanisms-based approach. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022 Mar; 18(3):133-45.

- Morand E, Merola JF, Tanaka Y, Gladman D, Fleischmann R. TYK2: An emerging therapeutic target in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2024 Apr; 20(4):232-40.

- Zhang K, Ye K, Tang H, Qi Z, Wang T, Mao J, et al. Development and therapeutic implications of tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2023 Apr 13; 66(7):4378-416.