Stem Cell Therapy for Myocardial Infarction: An Overview

Stem Cell Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction and Cardiomyopathy: The Emergency Medicine Perspective

John R. Richards, MD 1; Erik G. Laurin, MD 1; Verena Schandera, MD 1; Andrew E. Richards 1; Colin Wang, MD 2; Maria Teresita Moviglia Brandolino, MD 3; Gustavo A. Moviglia, MD, PhD 4

- Department of Emergency Medicine, UC Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, California, USA

- Department of Emergency Medicine, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California, USA

- Moviglia Method Clinic, Buenos Aires, Argentina

- Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Winston Salem, North Carolina, USA

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 September 2025

CITATION: RICHARDS, John R. et al. Stem Cell Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction and Cardiomyopathy: The Emergency Medicine Perspective. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 9, sep. 2025. ISSN 2375-1924. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6911>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6911

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Ischemic cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide. Patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiomyopathy are commonly treated in the emergency department, with emphasis on pharmacologic stabilization, thrombolysis, and expeditious transfer to percutaneous coronary intervention and/or the inpatient cardiac unit. The nexus between emergency medicine and regenerative medicine, which focuses on repair and restoration of damaged tissue, is just beginning. The use of stem cells, which are capable of extensive proliferation and differentiation into myriad lineage cells, are a key component of regenerative medicine. Over the past two decades, stem cell research has expanded and demonstrated benefit in animal and human studies of acute myocardial infarction and cardiomyopathy. However, stem cell treatment must be initiated early to achieve the best outcome. Emergency physicians may soon be involved in this regenerative process, with procurement and administration of stem cells during the initial stabilization of the acute cardiac patient in the emergency department. In this article, we discuss the emergency medicine perspective on the selection of specific types of stem cells and their adjuncts, route, timing, mechanisms of healing, relevant clinical scenarios, and review the evidence and safety behind this futuristic treatment.

Keywords

- Stem Cell Therapy

- Acute Myocardial Infarction

- Cardiomyopathy

- Emergency Medicine

- Regenerative Medicine

Introduction

Ischemic heart disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide. Based on estimates from the World Health Organization, more than 17 million people will die from ischemic heart disease this year, outpacing infectious diseases, cancer, and trauma combined. This number is predicted to increase to over 23 million by 2030, or nearly one-third of all global deaths. The definitive diagnosis and acute care of patients with ischemic heart disease almost always begins in the emergency department (ED). Patients with acute coronary syndromes such as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-STEMI (NSTEMI), unstable angina, and ischemic cardiomyopathy are routinely cared for by emergency physicians. Standard first-line treatment in the ED includes respiratory optimization, pharmacotherapy, and thrombolytics, followed by rapid triage to cardiac catheterization, inpatient cardiac service, or surgical consultation for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Tailored pharmacologic management and timely reperfusion/revascularization of the myocardium via thrombolysis and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can minimize infarct size and progression of cardiac remodeling. However, these treatments can neither completely halt cardiomyocyte destruction and subsequent fibrosis nor restore myocardial structure and function. At advanced stages, heart transplantation becomes the only effective treatment method but is limited by strict selection criteria and donor organ availability. Given these limitations, new approaches to acute cardiac care focusing on restoration and regeneration are desperately needed. Regenerative medicine and the use of stem cell therapy may be the solution, and emergency physicians in the future will initiate this aspect of care as soon as the patient arrives in the ED.

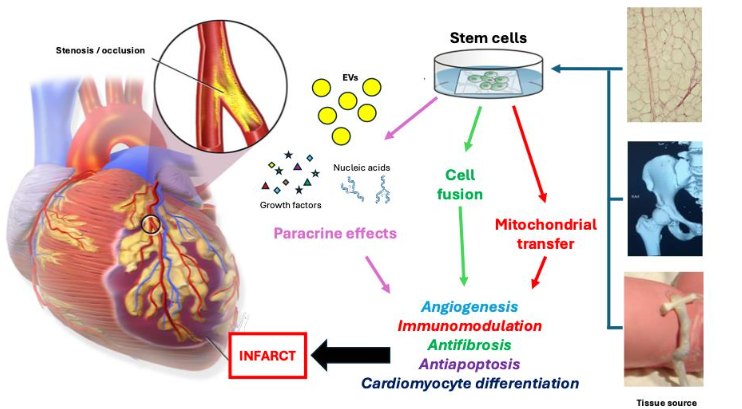

After acute injury, the heart has a limited ability to regenerate, relying primarily on activation of resident cardiac stem cells and recruitment of stem cells from adipose, bone marrow, and skeletal tissues. The annual cardiomyocyte turnover rate is estimated to be 1% in young adults and decreases to 0.5% in the elderly, and approximately half of human cardiomyocytes are renewed during their lifespan. Unfortunately, this endogenous repair capacity cannot cope with the extent of cardiomyocyte destruction after acute myocardial infarction. Stem cell therapy offers a promising new option for ischemic heart diseases because of the cells’ remarkable capacity for proliferation and differentiation. Stem cells can replace dysfunctional or dead cells and activate self-regenerative and reparative mechanisms. Stem cells can also prevent further damage from microenvironment modification, which includes immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory activity. Clinical research on the use of stem cells and cardiac disease over the past two decades has progressed to the point where this promising therapy may soon reside in the hands of emergency physicians. The reason behind this is that six major stem cell research breakthroughs have been achieved: 1) Establishment of safety with intravenous and intracoronary delivery; 2) Demonstration that therapeutic regeneration is possible; 3) Rise of allogeneic cell therapy; 4) Impact of increasing mechanistic insights; 5) Glimmers of clinical efficacy; and 6) Progression to phase 2 and 3 clinical studies. To date, there are over 100 clinical trials of stem cell therapy for acute myocardial infarction and over 90 for ischemic cardiomyopathies. Human trials show stem cell therapy is safe, regardless of the specific cell product, delivery route, dosing protocol, or patient characteristics. Over 24 cellular and gene therapy products have been licensed by the United States Office of Tissues and Advanced Therapies. In this article, we discuss the selection of specific types of stem cells and their adjuncts, mechanisms of healing, route and timing of stem cell delivery, relevant clinical scenarios, and review the evidence and safety behind this futuristic treatment.

Types of Stem Cells

Stem cells are undifferentiated cells which possess high self-renewal and proliferation properties and can differentiate into a wide range of lineage-specific cell types, making them an ideal source for tissue regeneration. Stem cells are classified based on their tissue of origin and differentiation ability. Pluripotent stem cells can differentiate into all cell types derived from the three germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm, ectoderm) and include embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and adult induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Multipotent adult stem cells, which can differentiate into various cell types of a single germ layer, include hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Selection of stem cell type is an important consideration with regard to timely access and use in treating patients in the ED with acute coronary syndromes.

AUTLOGOUS VERSUS ALLOGENIC

Autologous stem cells are obtained from patients’ own tissue and do not carry a risk for immunorejection and oncological potential. However, aging and co-morbidities may affect the quantity and quality of autologous stem cells, which must first be harvested from the patient before use. Sufficient time for cell processing and culturing is also required to produce stem cells of high quality and adequate number. A workaround to this problem is for a patient to have a stored sample of their own stem cells harvested and preserved in advance, allowing for rapid access if needed. In contrast, allogeneic stem cells are isolated from healthy donors with controlled quality and proliferation standards. Allogenic stem cells can be stored, retrieved, and administered “off-the-shelf,” which is useful for immediate ED and PCI use. However, immunological matching between host and donor may be required.

EMBRYONIC STEM CELLS

Embryonic stem cells are pluripotent cells arising from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst during embryonic development in mammals. They can differentiate to all adult cell types, enabling regeneration of damaged cardiomyocytes and electrical integration within the myocardium. This unique property of ESCs was highlighted in an animal study in which atrioventricular block was reversed after human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes were transplanted. In the first human trial from 2015 (ESCORT), patients with advanced ischemic heart disease undergoing open heart surgery received ESC-derived cardiac progenitor cells. These cells were integrated into a fibrin patch directly placed on the infarct zone, with reported symptomatic improvement and 10% gain in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Although ESCs have powerful regenerative and pluripotent capabilities, these stem cells are the most ethically and politically controversial, as their origin is from human embryos. Governmental regulations limit or prohibit their use in many countries. Since these stem cells originate from a different person, a risk of immune rejection exists, and long-term immunosuppressive medication may be required for ESC survival. Tumor formation, such as teratoma, is another risk of ESC therapy. As a result, most of the research in this area has focused on adult stem cells instead, and emergency use of ESCs seems unlikely at this juncture.

UMBILICAL CORD

Stem cells from the umbilical cord can be stored postnatally at hospital biobanks and easily obtained thereafter, and these stem cells represent a potential “off the shelf” supply in cases of acute need in the ED or coronary catheterization lab. Wharton’s jelly is gelatinous tissue in the umbilical cord that surrounds and protects umbilical vessels, and Wharton’s jelly-derived MSCs originate from embryonic mesodermal tissue at day 13 of embryonic development. These stem cells retain both embryonic and MSC properties and may have a higher potential for cardiomyocyte regeneration compared to autologous stem cells. The results of the first human study of these stem cells were published in 2015. In the WJ-MSC-AMI trial, patients with STEMI received intracoronary allogeneic Wharton’s jelly stem cells into the infarct-related coronary artery between five to seven days following reperfusion therapy. This experimental treatment improved myocardial viability, function, infarct area perfusion, LVEF, and prevention of adverse ventricular remodeling at 18 months. In addition to Wharton’s jelly, stem cells derived from umbilical cord blood have been shown to promote cardiac angiogenesis and immunogenicity. Intravenous delivery of umbilical cord blood stem cells in a large animal model of acute myocardial infarction preserved left ventricular function and enhanced myocardial regeneration. These cardioprotective effects are attributed to paracrine factors, which promote angiogenesis, limit inflammation, and preserve intracellular gap junctions, rather than direct cardiomyocyte contact and implantation within the heart.

INDUCED PLURIPOTENT STEM CELLS

Induced pluripotent stem cells are derived from fully differentiated somatic cells of various adult tissues. Through viral- and chemical-directed gene therapy, these cells can be reprogrammed to revert to a pluripotent, embryonic-like state. The first report of this technique appeared in 2006 and involved reprogramming adult mice fibroblasts into ESC-like cells utilizing genetic transcription factors. To circumvent the issues associated with the use of ESCs, iPSCs were generated from human fibroblasts and subsequently trialed for cardiac regenerative therapy. In vitro, cardiac progenitor cells generated from human iPSCs have been shown to express cardiac proteins and develop into cardiomyocytes with spontaneously beating sarcomeres responsive to action potentials and adrenergic stimulation. These cells have also demonstrated the ability to differentiate into atrial, ventricular, and nodal cell lineages. On the surface, these attributes would seem to give iPSCs the advantage over other adult tissue stem cells for cell therapy of ischemic heart disease. However, there are still challenges facing the use of iPSCs, such as extraction and processing methods resulting in issues with cell heterogeneity, purity, and difficulty with identification of potential teratoma-forming cells. Immunogenicity is another drawback, though it may be resolved using patient-specific autologous cells or donors who are homozygous at human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles. A review published this year assessed 115 human iPSC clinical trials with over 1,200 subjects with no generalizable safety concerns. The biobanking of allogenic iPSCs can provide a ready “off the shelf” supply of stem cells for emergency use, while eliminating the need to prepare limited doses of autologous cells for a specific patient.

CARDIAC STEM CELLS

Cardiac stem cells (CSCs) are a heterogeneous cell population found only in the heart with a greater capacity to differentiate into cardiomyocytes than other types of stem cells. Like MSCs, CSCs possess immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive properties. Unfortunately for the sake of emergency use, CSCs can only be harvested from biopsy of the heart. Subpopulations of CSCs include cardiosphere-derived cells, cardiac side population cells, mesangioblasts, and epicardial progenitors. A 2016 meta-analysis by Samanta and associates presented data on 80 animal studies of preclinical CSC therapy after myocardial infarction with 10.7% overall improvement in LVEF. In humans, early clinical trial results of allogenic cardiosphere-derived cells (CADUCEUS, ALLSTAR) reported positive results, with improved LVEF and decreased infarct size. Cardiopoietic bone marrow-derived MSCs are MSCs that have been modified by exposing them to a specific cocktail to promote cardiovascular lineage commitment and enhance their therapeutic potential. The first human study utilizing these cells was the C-CURE trial of 2013, in which subjects with cardiomyopathy received transendocardial cardiopoietic cells. At six months, there was improved LVEF and six-minute walking distance compared to standard care. This was followed by a larger trial by the same study group in 2017 (CHART-1) that reported more neutral results than its predecessor. The positive therapeutic effect from these cells is believed to be from paracrine signaling and direct interaction with endogenous CSCs, resulting in proliferation and differentiation into cardiomyocytes.

BONE MARROW MONONUCLEAR CELLS

The cell composition of bone marrow is heterogenous and includes monocytes, lymphocytes, MSCs, HSCs, and endothelial progenitor cells. Autologous bone marrow stem cells were first tested in 2001 for successful treatment of myocardial infarction in mice. For the past two decades, autologous bone marrow stem cells have been the most frequently used stem cell type in human clinical trials for treating ischemic heart disease. Early phase I trials (TOPCARE-AMI, BOOST) demonstrated improvement in perfusion and left ventricular function after intracoronary bone marrow mononuclear stem cell infusion, while confirming safety and practicability. Further human clinical trials (TCT-STAMI, REPAIR-AMI, BALANCE) reported similar positive findings. A Cochrane review of 33 clinical trials of post-acute myocardial infarction bone marrow mononuclear stem cell therapy confirmed lasting improvement in LVEF in long-term follow-up periods. Two years later a second Cochrane review of 23 clinical trials involving bone marrow mononuclear stem cell therapy for ischemic heart disease and cardiomyopathy corroborated earlier findings and further concluded that the long-term gains in LVEF decreased morbidity and mortality. However, later clinical trials (LateTIME, SWISS-AMI, TIME) did not show similar improvements in left ventricular recovery. These mixed results may be explained from the heterogeneous cell composition of bone marrow, making it difficult to determine which cell types, such as HSCs versus MSCs, are responsible for the observed clinical effects or lack thereof. Differences in isolation, preservation, quantity, quality, timing, study endpoints, and patient age, gender, and co-morbidities are also possible contributors for the mixed results. The procurement of bone marrow mononuclear stem cells for use in acute care requires bone marrow aspiration, a painful and invasive procedure that often results in an insufficient yield of cells, especially in older patients. As such, bone marrow may not represent the best autologous source of stem cells for emergency use.

Hematopoietic Stem Cells

Bone marrow HSCs are blood-forming cells that give rise to the erythroid lineage (red blood cells), the megakaryocytic lineage (platelets), and the myeloid and lymphoid lineage (immune system cells). Only one in 10,000 marrow cells are HSCs. These stem cells possess surface markers CD34, CD45, CD133, and CD117 (c-kit, the receptor for stem cell factor) and others, which enable their isolation from other bone marrow cell types. Bone marrow-derived CD34+ or CD133+ cells have specifically been used in human clinical trials. The REGENT trial of 2009 compared the effectiveness of intracoronary administration of either non-selected bone marrow mononuclear cells or CD34+CXCR4+ HSCs in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Both treatment groups showed a 3% increase in LVEF at six-month follow-up. The COMPARE-AMI trial of 2011 involved intracoronary administration of CD133+ HSCs in acute myocardial infarction patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Four-month follow-up revealed significant gains in LVEF with no adverse events. In addition to bone marrow, CD34+ cells are found in peripheral blood and other tissues, providing alternative sources for harvesting. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor has been used to mobilize CD34+ cells from the bone marrow to peripheral blood. This method was used in a 2011 study involving intramyocardial injection of autologous CD34+ cells in patients with refractory angina, which proved successful in reducing symptom frequency while improving exercise tolerance.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Bone marrow MSCs represent the non-hematopoietic population of bone marrow cells. They are multipotent and thus able to differentiate into a limited number of cell types of mesenchymal lineage, such as myocytes, adipocytes, osteocytes, chondrocytes, and marrow stroma. These MSCs can be distinguished from HSCs based on the absence of surface markers CD34 and CD45, and presence of CD73, CD105, CD29, CD44, and CD90. Bone marrow MSCs are able to integrate into cardiac tissue, differentiate into cardiomyocytes and vascular endothelial cells, and recruit cardiac stem cells (CSCs) for repair and regeneration after infarction. The 2009 Prochymal trial showed improved LVEF and overall symptoms after treatment with intravenous allogenic bone marrow MSCs. In the 2014 PROMETHEUS trial, patients with cardiomyopathy undergoing CABG received intramyocardial autologous bone marrow MSCs, resulting in a 10% and 25% increase in LVEF and stroke volume, as well as an 8% reduction in cardiac scar tissue mass. The TAC-HFT trial of the same year compared transendocardial administration of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells versus MSCs in 65 patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. At 12 months there was improved quality of life but no improvement in LVEF in either group, and MSCs (but not mononuclear cells) reduced myocardial scar size and increased six-minute walking distance. The 2015 MSC-HF trial of patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy who underwent transendocardial injection of autologous bone marrow MSCs reported improvement in LVEF and end-systolic volume, myocardial mass, and quality of life. Both MSC-HF and the similar TRIDENT study published the following year reported on the effect of higher doses of stem cells resulting in greater gains in LVEF. The largest trial of cell therapy to date is DREAM-HF, a phase III study conducted in 55 sites across North America with a total of 565 patients with ischemic/non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Subjects who received transendocardial injection of allogeneic bone marrow MSCs had increased LVEF, decreased risk of myocardial infarction, and fewer major adverse cardiovascular events.

Advantages for Emergency Use

Allogeneic MSCs from any source have several advantages for use in emergency medicine. These stem cells possess anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and immunomodulatory properties. The lack of major histocompatibility class (MHC) II antigens, T- and B-cell cytokine secretion, and lymphocyte proliferation characterize MSCs as immunoprivileged and immunosuppressive. Allogenic MSCs have been successfully used to decrease graft rejection and treat graft-versus-host disease. Comparison of allogeneic and autologous bone marrow MSCs from the human POSEIDON and POSEIDON DCM trials demonstrated similar LVEF gains and safety in patients with ischemic heart disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing autologous to allogeneic MSCs in large animal studies of ischemic heart disease showed similar results for both. Both allogeneic and autologous MSC therapies had minimal side effects, including immunologic responses, confirming the safety of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells and providing support for their continued use. Another advantage of allogeneic MSCs for emergency use is their potential as an “off-the-shelf” supply, precluding the need to obtain and expand bone marrow from the patient and providing product consistency. However, one issue with this scenario is poor post-transplant engraftment and survival of MSCs from bone marrow or any source, which may be from the hypoxic, ischemic, or infarcted environment of the cardiac tissue. Evidence suggests that the therapeutic effect of MSCs is not from direct integration into cardiac tissue, but from paracrine signaling to direct repair and regeneration. This includes activation of endogenous CSCs, release of growth factors, angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and extracellular matrix stabilization. This is advantageous for use in emergency medicine, as therapeutic benefit may be achieved through intravenous and intracoronary routes, without the need for direct myocardial implantation, injection, or patch grafting of MSCs.

EXTRACELLULAR VESICLES

An important aspect of paracrine signaling is stem cell secretion of cell-free extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are small lipid membrane-enclosed vesicles which can carry diverse combinations of nucleic acids, proteins, lipids, peptides, and carbohydrates for intercellular signaling. The nucleic acids, including DNA, mRNA, and microRNA, transported by EVs can direct gene expression, translation, and modification in their target cells. Preclinical research has shown EVs have regenerative effects in the ischemic heart by modulating apoptosis, inflammation, fibrosis, and angiogenesis. The cardioprotective effects of EVs are mainly mediated through microRNAs. There are myriad cardiac-related microRNAs, each with different functions such as modulation of fibrosis, angiogenesis, apoptosis, and regulation of structural genes. Cell-free therapy utilizing EVs has several advantages in the context of emergency use. Unlike stem cells, EVs do not carry risk of replication and malignant and/or misguided transformation. The miniscule size of EVs minimizes risk of intracoronary thrombosis and dysrhythmia, and EVs can be administered intravenously and during PCI. Lastly, EVs do not evoke an immune response, thus obviating the need for immunosuppression, and their isolation, expansion, and storage requirements are less complex than stem cells.

ADIPOSE STEM CELLS

The subcutaneous adipose tissue is composed of adipocytes and a stromal-vascular fraction (SVF). Like bone marrow, this SVF contains a heterogeneous population of mononuclear cells, including preadipocytes, endothelial cells, macrophages, fibroblasts, MSCs and other progenitors cells with varying degrees of differentiation. The tissue microenvironments of bone marrow and adipose tissue differ significantly. This is important because MSCs interact with neighboring cells, such as osteoblasts in the bone marrow and vascular cells from adipose tissue. Because of this, adipose mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs) have greater angiogenic potential than bone marrow MSCs, but like bone marrow HSCs, are also capable of hematopoiesis. Adipose mesenchymal stem cells have several additional advantages over bone marrow MSCs. Preclinical studies have shown ASCs differentiate into cardiomyocytes and vascular cells at a higher percentage than bone marrow MSCs, while having greater immunomodulatory effects. In addition to their angiogenic capacity, ASCs have anti-inflammatory effects and do not express HLAs and other co-stimulatory molecules involved in immune recognition. As such, ASCs have great potential for allogeneic therapy. Unlike the invasive and painful bone marrow aspiration procedure with low yield, the liposuction harvest procedure is simpler and less painful. Adipose tissue yields significantly higher concentrations of stem cells than in bone marrow (5% versus 0.01% respectively). Liposuction is commonly performed worldwide during elective aesthetic and bariatric surgery, and the removed lipoaspirate containing potentially useful ASCs is discarded as medical waste. In the first human clinical trial (APOLLO) in 2012, the safety and effectiveness of intracoronary administration of autologous ASCs were assessed in patients with acute myocardial infarction, and the results were encouraging. A 4% increase in LVEF, reduction of the infarcted area, significant improvement in perfusion, and no adverse events were reported by the study group. The PRECISE trial of 2014 examined the effects of transendocardial autologous ASCs in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and showed improvement in cardiac wall motion and peak VO2. The study confirmed safety and feasibility, but LVEF was not significantly improved. The use of adipose tissue SVF has also been studied. A Phase 1/2 clinical trial investigated the safety of intramyocardial SVF in patients with ischemic heart disease, with significantly increased LVEF and improved six-minute walk test at follow up compared to baseline and no significant adverse effects. The MyStromalCell study of 2017 evaluated the effect of intramyocardial vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-stimulated SVF in patients with ischemic heart disease and refractory angina. Angina frequency and metabolic equivalent performance was reduced significantly during the three-year follow-up period. These SVF trials were followed by the ATHENA trials I and II, with intramyocardial administration of autologous ASCs for chronic severe ischemic heart disease patients with similar positive results. The most recent SCIENCE II trial published last year showed intramyocardial injection of allogeneic ASCs in patients with cardiomyopathy was safe and improved LVEF, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, and self-reported health. The paracrine effect of ASCs after transplantation is the main mechanism contributing to cardiac restoration and regeneration. The growth factors VEGF-A, VEGF-D, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and interleukin (IL)-8 are expressed at higher levels in ASCs than in other stem cells. In addition to the dominant paracrine effects of ASCs, such as the production of trophic factors, ASCs also promote regeneration through cell–cell (juxtacrine) direct contact. Direct cell fusion between ASCs and cardiomyocytes contributes to cardiac restoration and regeneration by producing new cardiomyocytes in response to damage. In vitro studies showed combining ASCs with cardiomyocytes induced reprogramming back to a progenitor-like state. Resultant hybrid cells displayed early cardiac commitment and proliferation markers, along with cardiomyocyte-like morphology and spontaneous rhythmic contraction. Electrophysiological studies revealed the presence of functional voltage-dependent potassium and calcium channels in these differentiated cardiomyocytes. Direct transfer of mitochondria through gap junctions and tunneling nanotubes represents another mechanism underlying the therapeutic effects of ASCs, rescuing ischemic cardiomyocytes from cell death. Donor mitochondrial DNA from ASCs has been found in the recipient myocardium in parallel with enhanced cardiac function.

Priming, Dosage, Timing, and Delivery

Priming of MSC cultures using growth factors such as fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), and transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-α) can improve regenerative potential and survival through increased secretion of VEGF and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF). Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-1, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) have been observed to promote MSCs to release anti-inflammatory signals and enhance their immunosuppressive function. The process of hypoxia and re-oxygenation during MSC culturing can stimulate the expression of various pro-survival genes and pro-angiogenic factors, enhancing migration towards the ischemic site while increasing tolerance to ischemic microenvironments after transplantation. Pharmacologic agents such as angiotensin receptor blockers, statins, anesthetics, oxytocin, trimetazidine, and vitamin E have also been used for pre-treatment of MSCs to improve their survivability. Additionally, mechanical conditioning, such as the application of shear stress and cyclic stretch, has been shown to promote differentiation of MSCs into cardiomyocytes, by mechanical growth factors present in native cardiomyocytes.

The ideal dosage of stem cells to achieve therapeutic effect remains in question. On average, one billion cardiomyocytes are lost after acute myocardial infarction. Prior studies have employed a wide variability of stem cell dosages ranging from 1 × 106 to 2 × 108 cells, which are much lower than cell loss after myocardial injury. Since stem cell survival and engraftment after administration is low, larger doses of cells may be required to regenerate injured myocardium. However, large doses of cells may cause aggregates, increasing thrombotic and dysrhythmic risk. Conversely, a few clinical trials have demonstrated that lower doses of cells are more effective than higher doses, particularly in terms of enhancing paracrine and immunoprotective effects, angiogenesis activation, and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy induction. Other investigators have suggested repeated doses could yield more substantial benefits compared to a single dose, which is best accomplished via the intravenous route. Several trials focused on the impact of stem cell therapy timing on therapeutic potential with mixed results. In the future, it is likely that high, repeated administrations of intravenous stem cells initiated in the ED will be standard of care.

Multiple methods of stem cell delivery have been studied, including intravenous, intracoronary, intramyocardial, transendocardial, retrograde intracoronary sinus, open surgical epicardial injection, intrapericardial, epicardial patching, and scaffolding. Direct injection or implantation guarantees adequate blood supply to the cell to provide the highest potential for cell retention, engraftment, and remuscularization but exhibits minimal paracrine effects. The intracoronary route has been commonly used in past studies but has disadvantages, including limited cell retention due to rapid washout and limitations on dosage of cells to prevent downstream obstruction of coronary arteries. These invasive and technically challenging techniques carry the risk of myocardial and vascular perforation, emboli, and dysrhythmia. Intravenous infusion of stem cells is one of the most common and safest methods of delivery, maximizing paracrine effects and minimizing post-transplantation inflammation. However, one limitation remains that the majority of intravenous stem cells become trapped in the lung or the reticuloendothelial system, but which may be overcome by prominent paracrine and EV effects.

Human Studies and Safety

HUMAN STUDIES

In addition to the aforementioned studies, there have been several systematic reviews and meta-analyses focusing on stem cell therapy of ischemic heart disease from the past five years. The most recent systematic review by Ali and associates published this year identified 20 clinical trials utilizing MSCs, iPSCs, and ESCs. Their overall findings confirmed therapeutic benefits, including improvements in LVEF and reductions in infarct size. Key clinical trials highlighted by the authors included BAMI from 2020, one of the largest multicenter trials with 375 subjects, which compared intracoronary autologous bone marrow-derived mononuclear cell infusion to standard care. Results showed a 3% improvement in LVEF and reduced infarct size but not enhanced survival. The C-CURE trial of 2013 tested cardiopoietic stem cells derived from bone marrow MSCs exposed to a “cardiac cocktail” for chronic heart failure, with the findings of 7% LVEF improvement, better exercise capacity, and quality of life compared to controls. A meta-analysis of MSC trials from last year by Seyiglohu et al identified 49 total with 1,408 subjects with the overall findings of a 5.75% increase in LVEF from baseline. There were 33 trials in which 80 deaths were reported following MSC administration. However, 33 (41.3%) of these deaths were not related to the intervention itself, and another 40% had no reported cause. A systematic review also from last year by Abouzid and colleagues identified 35 trials and confirmed overall improvement in LVEF and safety. A 2022 meta-analysis of percutaneous endomyocardial stem cell therapy in patients with ischemic heart failure by Gyöngyösi and associates queried the ACCRUE database and highlighted 18 trials and 1,715 subjects. Significant increases in LVEF and decreases in end-systolic volume and NYHA functional classifications were reported, while emphasizing safety of the percutaneous approach. Finally, a 2020 meta-analysis of MSC therapy for cardiomyopathy by Fu and Chen assessed six trials and reported significant improvements in LVEF and reduced rehospitalization rates, but no influence on mortality.

SAFETY

Immune response is another area of safety concern. For example, ASCs exhibit low expression of class II major histocompatibilty complex and inhibit T- and B-cell responses. In a phase I safety trial, “off the shelf” allogenic ASCs were administered to patients without matching patient serotypes, relying instead on the immunosuppressive properties of the ASCs. Although some subjects developed donor specific HLA antibodies after treatment, no clinical complications occurred, and improvements were seen in cardiac contractility, diastolic filling, NYHA functional classification, and exercise capacity.

Conclusion

Despite the progress of conventional therapies such as pharmacological agents (thrombolytics, anticoagulants, antiplatelets) and interventional therapies (PCI, CABG), the overall therapeutic effect on damaged myocardium in patients with acute myocardial infarction and ischemic cardiomyopathy remains limited. Current treatment strategies in emergency medicine focus mainly on protecting myocardial tissue from cell death, limiting acute damage, delaying the progress of cardiomyopathy, but not cardiac regeneration and restoration. As such, there is a critical need for alternative approaches. We believe the use of stem cells and cell-free therapy, such as EVs and other nanoparticles, will be incorporated into initial treatment strategies for emergency physicians caring for patients with acute coronary syndromes. This will likely expand to other ED clinical scenarios as well, including sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute kidney injury, corneal injury, and radiation exposure. There has been significant progress in understanding the mechanisms behind the homing of stem cells and their paracrine effects, as well as associated growth factors and bioactive agents. Further randomized human trials initiated in the ED and coronary catheterization lab will be required to accelerate this process. Standardization of study protocols, stem cell type, subject selection criteria, endpoints, and follow-up will be necessary to avoid the methodological heterogeneity of past stem cell studies.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding Statement

None

References

- Leading causes of death. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death

- Premer C, Schulman IH, Jackson JS. The role of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in the acute clinical setting. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:572-578. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.11.035

- Assmus B, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Cardiac Cell Therapy. Circ Res. 2015;116(8):1291-1292. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306330

- Öztürk S, Elçin AE, Koca A, Elçin YM. Therapeutic Applications of Stem Cells and Extracellular Vesicles in Emergency Care: Futuristic Perspectives. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2021;17(2):390-410. doi:10.1007/s12015-020-10029-2

- Ali SA, Mahmood Z, Mubarak Z, et al. Assessing the Potential Benefits of Stem Cell Therapy in Cardiac Regeneration for Patients With Ischemic Heart Disease. Cureus. 2025;17(1):e76770. doi:10.7759/cureus.76770

- Marbán E. Breakthroughs in Cell Therapy for Heart Disease: Focus on Cardiosphere-Derived Cells. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(6):850-858. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.02.014

- Chepeleva EV. Cell Therapy in the Treatment of Coronary Heart Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(23):16844. doi:10.3390/ijms242316844

- Skrypnyk M. Current progress and limitations of research regarding the therapeutic use of adipose-derived stem cells: literature review. J Umm Al-Qura Univ Appl Sci. 2025;11(1):63-75. doi:10.1007/s43994-024-00147-9

- Rheault-Henry M, White I, Grover D, Atoui R. Stem cell therapy for heart failure: Medical breakthrough, or dead end? World J Stem Cells. 2021;13(4):236-259. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v13.i4.236

- Boyle AJ, Schulman SP, Hare JM, Oettgen P. Is stem cell therapy ready for patients? Stem Cell Therapy for Cardiac Repair. Ready for the Next Step. Circulation. 2006;114(4):339-352. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.105.590653

- Chakravarti AR, Pacelli S, Alam P, et al. Pre-Conditioning Stem Cells in a Biomimetic Environment for Enhanced Cardiac Tissue Repair: In Vitro and In Vivo Analysis. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2018;11(5):321-336. doi:10.1007/s12195-018-0543-x

- Xue T, Cho HC, Akar FG, et al. Functional integration of electrically active cardiac derivatives from genetically engineered human embryonic stem cells with quiescent recipient ventricular cardiomyocytes: insights into the development of cell-based pacemakers. Circulation. 2005;111(1):11-20. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000151313.18547.A2

- Menasché P, Vanneaux V, Hagège A, et al. Transplantation of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Cardiovascular Progenitors for Severe Ischemic Left Ventricular Dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(4):429-438. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.047

- Menasché P, Vanneaux V, Hagège A, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiac progenitors for severe heart failure treatment: first clinical case report. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(30):2011-2017. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv189

- Dhar D, Hsi-En Ho J. Stem cell research policies around the world. Yale J Biol Med. 2009;82(3):113-115.

- Lin Q, Fu Q, Zhang Y, et al. Tumourigenesis in the infarcted rat heart is eliminated through differentiation and enrichment of the transplanted embryonic stem cells. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12(11):1179-1185. doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hfq144

- Brizard CP, Elwood NJ, Kowalski R, et al. Safety and feasibility of adjunct autologous cord blood stem cell therapy during the Norwood heart operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;166(6):1746-1755. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2023.07.035

- Ahmed MM, Meece LE, Handberg EM, et al. Intravenous administration of umbilical cord lining stem cells in left ventricular assist device recipients: Results of the uSTOP LVAD BLEED pilot study. JHLT Open. 2024;3:100037. doi:10.1016/j.jhlto.2023.100037

- Troyer DL, Weiss ML. Wharton’s jelly-derived cells are a primitive stromal cell population. Stem Cells Dayt Ohio. 2008;26(3):591-599. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0439

- Kim DW, Staples M, Shinozuka K, Pantcheva P, Kang SD, Borlongan CV. Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells: phenotypic characterization and optimizing their therapeutic potential for clinical applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(6):11692-11712. doi:10.3390/ijms140611692

- Gao LR, Chen Y, Zhang NK, et al. Intracoronary infusion of Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells in acute myocardial infarction: double-blind, randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2015;13:162. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0399-z

- Roura S, Bagó JR, Soler-Botija C, et al. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote vascular growth in vivo. PloS One. 2012;7(11):e49447. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049447

- Lim M, Wang W, Liang L, et al. Intravenous injection of allogeneic umbilical cord-derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells reduces the infarct area and ameliorates cardiac function in a porcine model of acute myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):129. doi:10.1186/s13287-018-0888-z

- Correa A, Ottoboni GS, Senegaglia AC, et al. Expanded CD133+ Cells from Human Umbilical Cord Blood Improved Heart Function in Rats after Severe Myocardial Infarction. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:5412478. doi:10.1155/2018/5412478

- Liu C, Kang LN, Chen F, et al. Immediate Intracoronary Delivery of Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Reduces Myocardial Injury by Regulating the Inflammatory Process Through Cell-Cell Contact with T Lymphocytes. Stem Cells Dev. 2020;29(20):1331-1345. doi:10.1089/scd.2019.0264

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861-872. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663-676. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024

- Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318(5858):1917-1920. doi:10.1126/science.1151526

- Zhang J, Wilson GF, Soerens AG, et al. Functional cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circ Res. 2009;104(4):e30-41. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192237

- Blin G, Nury D, Stefanovic S, et al. A purified population of multipotent cardiovascular progenitors derived from primate pluripotent stem cells engrafts in postmyocardial infarcted nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(4):1125-1139. doi:10.1172/JCI40120

- Dixit P, Katare R. Challenges in identifying the best source of stem cells for cardiac regeneration therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6(1):26. doi:10.1186/s13287-015-0010-8

- Ahmed RPH, Ashraf M, Buccini S, Shujia J, Haider HK. Cardiac tumorigenic potential of induced pluripotent stem cells in an immunocompetent host with myocardial infarction. Regen Med. 2011;6(2):171-178. doi:10.2217/rme.10.103

- Rais Y, Zviran A, Geula S, et al. Deterministic direct reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Nature. 2013;502(7469):65-70. doi:10.1038/nature12587

- Kirkeby A, Main H, Carpenter M. Pluripotent stem-cell-derived therapies in clinical trial: A 2025 update. Cell Stem Cell. 2025;32(1):10-37. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2024.12.005

- Ortuño-Costela MDC, Cerrada V, García-López M, Gallardo ME. The Challenge of Bringing iPSCs to the Patient. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(24):6305. doi:10.3390/ijms20246305

- He JQ, Vu DM, Hunt G, Chugh A, Bhatnagar A, Bolli R. Human cardiac stem cells isolated from atrial appendages stably express c-kit. PloS One. 2011;6(11):e27719. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027719

- Madigan M, Atoui R. Therapeutic Use of Stem Cells for Myocardial Infarction. Bioeng Basel Switz. 2018;5(2):28. doi:10.3390/bioengineering5020028

- Moccetti T, Leri A, Goichberg P, Rota M, Anversa P. A Novel Class of Human Cardiac Stem Cells. Cardiol Rev. 2015;23(4):189-200. doi:10.1097/CRD.000000000000064

- Samanta A, Dawn B. Meta-Analysis of Preclinical Data Reveals Efficacy of Cardiac Stem Cell Therapy for Heart Repair. Circ Res. 2016;118(8):1186-1188. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308620

- Makkar RR, Kereiakes DJ, Aguirre F, et al. Intracoronary ALLogeneic heart STem cells to Achieve myocardial Regeneration (ALLSTAR): a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(36):3451-3458. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa541

- Malliaras K, Makkar RR, Smith RR, et al. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells after myocardial infarction: evidence of therapeutic regeneration in the final 1-year results of the CADUCEUS trial (CArdiosphere-Derived aUtologous stem CElls to reverse ventricUlar dySfunction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(2):110-122. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.724

- Bartunek J, Behfar A, Dolatabadi D, et al. Cardiopoietic stem cell therapy in heart failure: the C-CURE (Cardiopoietic stem Cell therapy in heart failURE) multicenter randomized trial with lineage-specified biologics. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(23):2329-2338. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.071

- Bartunek J, Terzic A, Davison BA, et al. Cardiopoietic cell therapy for advanced ischaemic heart failure: results at 39 weeks of the prospective, randomized, double blind, sham-controlled CHART-1 clinical trial. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(9):648-660. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw543

- Oh H, Bradfute SB, Gallardo TD, et al. Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium: homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(21):12313-12318. doi:10.1073/pnas.2132126100

- Micheu MM, Dorobantu M. Fifteen years of bone marrow mononuclear cell therapy in acute myocardial infarction. World J Stem Cells. 2017;9(4):68-76. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v9.i4.68

- Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, et al. Mobilized bone marrow cells repair the infarcted heart, improving function and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(18):10344-10349. doi:10.1073/pnas.181177898

- Nigro P, Bassetti B, Cavallotti L, Catto V, Carbucicchio C, Pompilio G. Cell therapy for heart disease after 15 years: Unmet expectations. Pharmacol Res. 2018;127:77-91. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2017.02.015

- Assmus B, Schächinger V, Teupe C, et al. Transplantation of Progenitor Cells and Regeneration Enhancement in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TOPCARE-AMI). Circulation. 2002;106(24):3009-3017. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000043246.74879.cd

- Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Lotz J, et al. Intracoronary autologous bone-marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: the BOOST randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2004;364(9429):141-148. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16626-9

- Schächinger V, Erbs S, Elsässer A, et al. Intracoronary Bone Marrow–Derived Progenitor Cells in Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(12):1210-1221. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060186

- Ge J, Li Y, Qian J, et al. Efficacy of emergent transcatheter transplantation of stem cells for treatment of acute myocardial infarction (TCT-STAMI). Heart Br Card Soc. 2006;92(12):1764-1767. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.085431

- Yousef M, Schannwell CM, Köstering M, Zeus T, Brehm M, Strauer BE. The BALANCE Study: clinical benefit and long-term outcome after intracoronary autologous bone marrow cell transplantation in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(24):2262-2269. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.051

- Clifford DM, Fisher SA, Brunskill SJ, et al. Stem cell treatment for acute myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(2):CD006536. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006536.pub3

- Fisher SA, Brunskill SJ, Doree C, Mathur A, Taggart DP, Martin-Rendon E. Stem cell therapy for chronic ischaemic heart disease and congestive heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD007888. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007888.pub2

- Traverse JH, Henry TD, Ellis SG, et al. Effect of intracoronary delivery of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells 2 to 3 weeks following acute myocardial infarction on left ventricular function: the LateTIME randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;306(19):2110-2119. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1670

- Sürder D, Manka R, Moccetti T, et al. Effect of Bone Marrow-Derived Mononuclear Cell Treatment, Early or Late After Acute Myocardial Infarction: Twelve Months CMR and Long-Term Clinical Results. Circ Res. 2016;119(3):481-490. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308639

- Traverse JH, Henry TD, Pepine CJ, et al. TIME Trial: Effect of Timing of Stem Cell Delivery Following ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction on the Recovery of Global and Regional Left Ventricular Function: Final 2-Year Analysis. Circ Res. 2018;122(3):479-488. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311466

- Harrison DE, Astle CM, Lerner C. Number and continuous proliferative pattern of transplanted primitive immunohematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(3):822-826. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.3.822

- Bongiovanni D, Bassetti B, Gambini E, et al. The CD133+ cell as advanced medicinal product for myocardial and limb ischemia. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23(20):2403-2421. doi:10.1089/scd.2014.0111

- Tendera M, Wojakowski W, Ruzyłło W, et al. Intracoronary infusion of bone marrow-derived selected CD34+CXCR4+ cells and non-selected mononuclear cells in patients with acute STEMI and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: results of randomized, multicentre Myocardial Regeneration by Intracoronary Infusion of Selected Population of Stem Cells in Acute Myocardial Infarction (REGENT) Trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(11):1313-1321. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp073

- Mansour S, Roy DC, Bouchard V, et al. One-Year Safety Analysis of the COMPARE-AMI Trial: Comparison of Intracoronary Injection of CD133 Bone Marrow Stem Cells to Placebo in Patients after Acute Myocardial Infarction and Left Ventricular Dysfunction. Bone Marrow Res. 2011;2011:385124. doi:10.1155/2011/385124

- Losordo DW, Henry TD, Davidson C, et al. Intramyocardial, autologous CD34+ cell therapy for refractory angina. Circ Res. 2011;109(4):428-436. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.245993

- Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143-147. doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.143

- Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315-317. doi:10.1080/14653240600855905

- Roura S, Gálvez-Montón C, Mirabel C, Vives J, Bayes-Genis A. Mesenchymal stem cells for cardiac repair: are the actors ready for the clinical scenario? Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8(1):238. doi:10.1186/s13287-017-0695-y

- Hare JM, Traverse JH, Henry TD, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of intravenous adult human mesenchymal stem cells (prochymal) after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(24):2277-2286. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.055

- Karantalis V, DiFede DL, Gerstenblith G, et al. Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells Produce Concordant Improvements in Regional Function, Tissue Perfusion and Fibrotic Burden when Administered to Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting – The PROMETHEUS Trial. Circ Res. 2014;114(8):1302-1310. doi:10.1161/circresaha.114.303180

- Heldman AW, DiFede DL, Fishman JE, et al. Transendocardial mesenchymal stem cells and mononuclear bone marrow cells for ischemic cardiomyopathy: the TAC-HFT randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(1):62-73. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.282909

- Florea V, Rieger AC, DiFede DL, et al. Dose Comparison Study of Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Patients With Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (The TRIDENT Study). Circ Res. 2017;121(11):1279-1290. doi:10.1161/circresaha.117.311827

- Perin EC, Borow KM, Henry TD, et al. Randomized Trial of Targeted Transendocardial Mesenchymal Precursor Cell Therapy in Patients With Heart Failure. JACC. 2023;81(9):849-863. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.061

- Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. The Lancet. 2004;363(9419):1439-1441. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16104-7

- Hare JM, DiFede DL, Rieger AC, et al. Randomized Comparison of Allogeneic Versus Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy: POSEIDON-DCM Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(5):526-537. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.009

- Hare JM, Fishman JE, Gerstenblith G, et al. Comparison of allogeneic vs autologous bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells delivered by transendocardial injection in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: the POSEIDON randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308(22):2369-2379. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.25321

- Jansen Of Lorkeers SJ, Eding JEC, Vesterinen HM, et al. Similar effect of autologous and allogeneic cell therapy for ischemic heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of large animal studies. Circ Res. 2015;116(1):80-86. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304872

- Sanganalmath SK, Bolli R. Cell therapy for heart failure: a comprehensive overview of experimental and clinical studies, current challenges, and future directions. Circ Res. 2013;113(6):810-834. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300219

- Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Gao F, Tse HF, Tergaonkar V, Lian Q. Paracrine regulation in mesenchymal stem cells: the role of Rap1. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(10):e1932. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.285

- Nauta AJ, Fibbe WE. Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. Blood. 2007;110(10):3499-3506. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-02-069716

- Yang J, Zhou W, Zheng W, et al. Effects of myocardial transplantation of marrow mesenchymal stem cells transfected with vascular endothelial growth factor for the improvement of heart function and angiogenesis after myocardial infarction. Cardiology. 2007;107(1):17-29. doi:10.1159/000093609

- Rezaie J, Rahbarghazi R, Pezeshki M, et al. Cardioprotective role of extracellular vesicles: A highlight on exosome beneficial effects in cardiovascular diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(12):21732-21745. doi:10.1002/jcp.28894

- Baptista LS. Adipose stromal/stem cells in regenerative medicine: Potentials and limitations. World J Stem Cells. 2020;12(1):1-7. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v12.i1.1

- Cousin B, Casteilla L, Laharrague P, et al. Immuno-metabolism and adipose tissue: The key role of hematopoietic stem cells. Biochimie. 2016;124:21-26. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2015.06.012

- DelaRosa O, Sánchez-Correa B, Morgado S, et al. Human adipose-derived stem cells impair natural killer cell function and exhibit low susceptibility to natural killer-mediated lysis. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(8):1333-1343. doi:10.1089/scd.2011.0139

- Houtgraaf JH, den Dekker WK, van Dalen BM, et al. First Experience in Humans Using Adipose Tissue–Derived Regenerative Cells in the Treatment of Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JACC. 2012;59(5):539-540. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.065

- Comella K, Parcero J, Bansal H, et al. Effects of the intramyocardial implantation of stromal vascular fraction in patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Transl Med. 2016;14(1):158. doi:10.1186/s12967-016-0918-5

- Qayyum AA, Mathiasen AB, Helqvist S, et al. Autologous adipose-derived stromal cell treatment for patients with refractory angina (MyStromalCell Trial): 3-years follow-up results. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):360. doi:10.1186/s12967-019-2110-1

- Qayyum AA, Frljak S, Juhl M, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells to treat patients with non-ischaemic heart failure: Results from SCIENCE II pilot study. ESC Heart Fail. 2024;11(6):3882-3891. doi:10.1002/ehf2.14925

- Hsiao STF, Asgari A, Lokmic Z, et al. Comparative analysis of paracrine factor expression in human adult mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, adipose, and dermal tissue. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(12):2189-2203. doi:10.1089/scd.2011.0674

- Acquistapace A, Bru T, Lesault PF, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells reprogram adult cardiomyocytes toward a progenitor-like state through partial cell fusion and mitochondria transfer. Stem Cells Dayt Ohio. 2011;29(5):812-824. doi:10.1002/stem.632

- Metzele R, Alt C, Bai X, et al. Human adipose tissue-derived stem cells exhibit proliferation potential and spontaneous rhythmic contraction after fusion with neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol. 2011;25(3):830-839. doi:10.1096/fj.09-153221

- Mori D, Miyagawa S, Kawamura T, et al. Mitochondrial Transfer Induced by Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation Improves Cardiac Function in Rat Models of Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. Cell Transplant. 2023;32:9636-897221148457. doi:10.1177/09636897221148457

- Che Y, Shimizu Y, Murohara T. Therapeutic Potential of Adipose-Derived Regenerative Cells for Ischemic Diseases. Cells. 2025;14(5):343. doi:10.3390/cells14050343

- Bui TVA, Hwang JW, Lee JH, Park HJ, Ban K. Challenges and Limitations of Strategies to Promote Therapeutic Potential of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Cell-Based Cardiac Repair. Korean Circ J. 2021;51(2):97-113. doi:10.4070/kcj.2020.0518

- Garcia JP, Avila FR, Torres RA, et al. Hypoxia-preconditioning of human adipose-derived stem cells enhances cellular proliferation and angiogenesis: A systematic review. J Clin Transl Res. 2022;8(1):61-70.

- Abd Emami B, Mahmoudi E, Shokrgozar MA, et al. Mechanical and Chemical Predifferentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Into Cardiomyocytes and Their Effectiveness on Acute Myocardial Infarction. Artif Organs. 2018;42(6):E114-E126. doi:10.1111/aor.13091

- Prockop DJ, Olson SD. Clinical trials with adult stem/progenitor cells for tissue repair: let’s not overlook some essential precautions. Blood. 2006;109(8):3147-3151. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-03-013433

- Mathur A, Fernández-Avilés F, Bartunek J, et al. The effect of intracoronary infusion of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells on all-cause mortality in acute myocardial infarction: the BAMI trial. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(38):3702-3710. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa651

- Bartunek J, Behfar A, Dolatabadi D, et al. Cardiopoietic stem cell therapy in heart failure: the C-CURE (Cardiopoietic stem Cell therapy in heart failURE) multicenter randomized trial with lineage-specified biologics. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(23):2329-2338. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.071

- Seyihoglu B, Orhan I, Okudur N, et al. 20 years of treating ischemic cardiomyopathy with mesenchymal stromal cells: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Cytotherapy. 2024;26(12):1443-1457. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2024.07.004

- Abouzid MR, Umer AM, Jha SK, et al. Stem Cell Therapy for Myocardial Infarction and Heart Failure: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Critical Analysis. Cureus. 2024;16(5):e59474. doi:10.7759/cureus.59474

- Gyöngyösi M, Pokushalov E, Romanov A, et al. Meta-Analysis of Percutaneous Endomyocardial Cell Therapy in Patients with Ischemic Heart Failure by Combination of Individual Patient Data (IPD) of ACCRUE and Publication-Based Aggregate Data. J Clin Med. 2022;11(11):3205. doi:10.3390/jcm11113205

- Fu H, Chen Q. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for heart failure: a meta-analysis. Herz. 2020;45(6):557-563. doi:10.1007/s00059-018-4762-7

- Wang Y, Yi H, Song Y. The safety of MSC therapy over the past 15 years: a meta-analysis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):545. doi:10.1186/s13287-021-02609-x

- Wuputra K, Ku CC, Wu DC, Lin YC, Saito S, Yokoyama KK. Prevention of tumor risk associated with the reprogramming of human pluripotent stem cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):100. doi:10.1186/s13046-020-01584-0

- Jeong JO, Han JW, Kim JM, et al. Malignant tumor formation after transplantation of short-term cultured bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in experimental myocardial infarction and diabetic neuropathy. Circ Res. 2011;108(11):1340-1347. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.239848

- Miura M, Miura Y, Padilla-Nash HM, et al. Accumulated chromosomal instability in murine bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells leads to malignant transformation. Stem Cells Dayt Ohio. 2006;24(4):1095-1103. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2005-0403

- Breitbach M, Bostani T, Roell W, et al. Potential risks of bone marrow cell transplantation into infarcted hearts. Blood. 2007;110(4):1362-1369. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-063412

- Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449(7162):557-563. doi:10.1038/nature06188

- Ji SQ, Cao J, Zhang QY, Li YY, Yan YQ, Yu FX. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells promote pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Braz J Med Biol Res Rev Bras Pesqui Medicas E Biol. 2013;46(9):758-