Anti-apoptotic PROTACs in Cancer Therapy: A Review

Anti-apoptotic Proteolysis Targeted Chimeras (PROTACs) in Cancer Therapy

Muturi Njoka, Divya Kamath, Stefan H. Bossmann

- Department of Cancer Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 January 2025

CITATION: Njoka, M., Kamath, D., et al., 2025. Anti-apoptotic Proteolysis Targeted Chimeras (PROTACs) in Cancer Therapy. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(1). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6284

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6284

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Targeted protein degradation is an emerging approach for novel drug discovery and basic research. Several degrader molecules have been developed including PROteolysis-TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs), specific and nongenetic Inhibitor of APoptosis protein (IAP)-dependent Protein ERasers (SNIPERs), IAP antagonists, deubiquitylase inhibitors, hydrophobic tagging molecules, and E3 modulators. The chimeric degrader molecules PROTACs and SNIPERs are made of linking a target protein-ligand to an E3 ubiquitin ligase binding ligand. This modular nature of these chimeric molecules supports versatile protein targets by substituting target ligands. They induce ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of the target protein in the cytosol via recruiting an E3 ubiquitin ligase to the target protein. The bridging of the target protein and the E3 ubiquitin ligase facilitates ubiquitylation of the protein and its proteasomal degradation. PROTACs chimeric molecules recruit von Hippel–Lindau or cereblon ubiquitin ligases, while SNIPERs induce simultaneous degradation of cIAP1/2 or XIAP together with the target proteins. Several B-cell Lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family anti-apoptosis proteins BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 are validated anticancer targets and are upregulated in various malignancies. Also, aberrant expression of cIAP1/2 and XIAP with a concomitant increase in apoptosis resistance has been reported. The dysregulation of BCL2 and IAP gene expression in cancer disease is mainly caused by upregulation of the bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) proteins. Degradation of the cellular anti-apoptosis proteins mentioned is a promising approach to induce apoptosis in tumor cells and overcome treatment resistance. Various types of protein degradation strategies have been developed and used. This article overviewed various chimeric compounds capable of inducing the degradation of anti-apoptosis proteins BCL2, BET, and IAP in cancer treatment.

Keywords: PROTACs, anti-apoptosis proteins, BCL2, BET, IAP, Cancer therapy

1. Introduction

Cancer is considered a global health problem, and despite the progress in treatment options, it will be responsible for an estimated number of 16.6 million deaths by 2040. Recent advances in cancer therapy including molecular targeted therapy have shown to be advantageous and, are preferred to the classical therapy approaches due to better efficacy and fewer side effects. The molecular targeted therapies which include small molecules and monoclonal antibodies, act specifically on the disease-causing pathway proteins and prevent activation of downstream pathways responsible for tumor growth and metastasis. Although these therapies have been used with substantial success, it’s limited to targeting only ~22% of the 20,300 protein-coding genes in the genome. The rest of the ~80% genome (non-protein coding) is considered undruggable using conventional small molecule inhibitors and hence cannot be used for targeted therapies. One other major limitation faced by targeted therapy is the development of drug resistance malignancies thus necessitating the development of novel strategies to improve cancer treatment and survival.

Targeted protein degradation (TPD), first proposed in 1999, utilizes the cell’s proteolysis-based machinery to eliminate the target protein. This concept was recognized as a novel therapeutic modality that could suppress any of the genome-coded proteins and, with recent advances in technology, TDP has reemerged as a major potential therapeutic tool. TPD technologies either, use the Ubiquitin-proteosome, endosome-lysosome, or autophagy-lysosome strategies to degrade the target proteins. The strategy is selected depending on the type of protein targeted. In this review, we will limit ourselves to the degradation of specific intracellular proteins, which can be carried out by one of the two pathways: the autophagy-lysosome system and/or the ubiquitin-proteosome system. In the autophagy-lysosome system, the autophagosome encapsulates intracellular proteins and organelles, and then degradation occurs by fusing with the lysosomes. In the contrary, the ubiquitin-proteosome system detects and degrades poly-ubiquitylated proteins into peptides using protease complex.

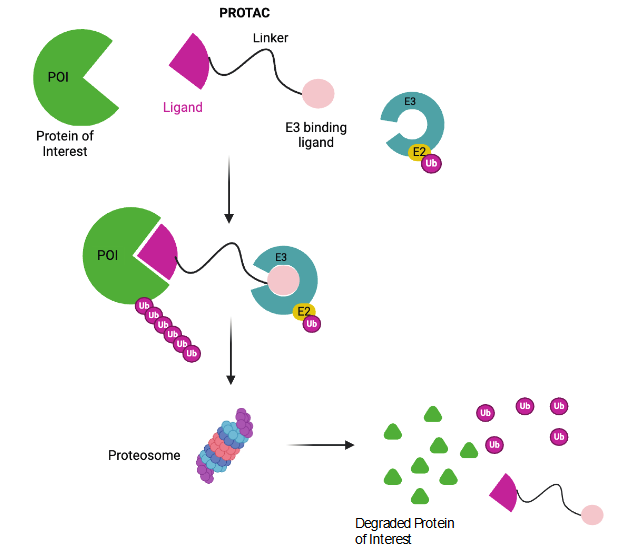

The PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) primarily use the Ub-proteosome pathway to degrade the targeted intracellular proteins. It is a small molecule consisting of 3 different parts; (i) a ligand to bind to the target protein, (ii) a ligand to bind to the E3 ligase to initiate degradation of the protein of interest, and (iii) a linker to connect both the ligands. This together forms a three-body polymer as shown in Figure 1. PROTACs assume a chimeric structure with E3 ubiquitin ligase or inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) ligand linked to target protein binding ligand. This brings the target protein spatially closer to the E3 ligase or IAP which results in subsequent polyubiquitylation of the target protein and its proteasomal degradation. The E3 ubiquitin ligases used so far in PROTACs are phosphorylated peptides and small-molecule ligands.

The PROTACs primarily use the ubiquitin-proteosome to induce target protein degradation in less than 24 hours. But in recent years they have been modified to utilize the proteosome, the autophagy, and the lysosome system. PROTACs-based technologies include Specific and Nongenetic IAP-dependent Protein ERasers (SNIPERs), auxin-inducible degron method, and E3 ubiquitin ligases modulators. One of the key advantages of these protein degraders is that any protein of interest can be targeted for degradation by rationally designing PROTACs or SNIPERs with substituted target ligands. Recently, PROTACs and SNIPERs which show tumor regression in vivo have been developed by refining E3 ubiquitin ligase ligands. CRL4 cereblon, CRL2 VHL, and IAPs are the most commonly used E3 ubiquitin ligases in cancer therapy. PROTACs and SNIPERs are used to degrade many target proteins as reviewed elsewhere. Over the last two decades, these molecules have seen a lot of advancement and development of subtypes being used in clinical trials. Several PROTACs are designed to induce protein degradation using antiapoptotic IAP proteins. This review will focus on the advances in PROTACs and SNIPERs targeting anti-apoptosis proteins including BCl2 family, IAP, and BET proteins.

2. Apoptosis and anti-apoptotic proteins

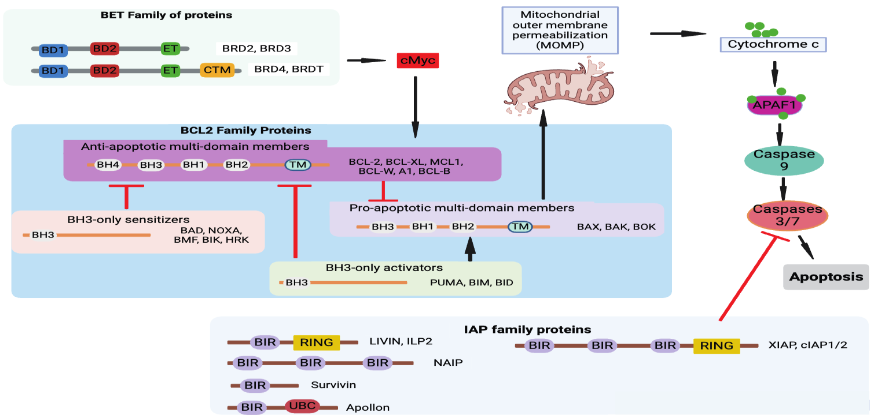

Apoptosis is a tightly regulated and evolutionally conserved process across metazoans. In vertebrates, it plays a critical role in proper morphological development, maintaining tissue homeostasis, and preventing cancer. Apoptosis is triggered by the internal or external stimuli that activate caspase proteases, either through an intrinsic pathway (mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) or extrinsic pathway (death-receptors (Fas and DR4/5) ultimately leading to cell death. Dysregulation of apoptosis is one of the hallmarks of cancer and can increase resistance to treatment in cancer cells. The intrinsic apoptosis pathway, triggered by cell distress signals, is regulated by the B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) family of proteins, which includes both pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members.

BH3-only protein initiates the apoptosis process by activating pro-apoptotic protein BAX/BAK and inhibiting anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins. Activated BAX/BAK oligomerize to insert into the cellular membrane phospholipids to induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP). This promotes the release of cytochrome c, the second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases (SMAC), and serine protease OMI. The SMAC and OMI bind and inactivate the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP). cytochrome c binds to apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 (APAF1) and caspase9 to form an apoptosome. This step commits the cell to apoptosis further activating caspases 3 and 7 to complete the process of apoptosis.

Several anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family proteins BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 are validated anticancer targets. The cancer cells upregulate anti-apoptotic proteins that inhibit pro-apoptotic BCL-2 members to dampen apoptosis. In addition, the deactivation of pro-apoptotic BH3-alone can lead to treatment-resistant cancers. The anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins are critical in tumor growth, and thus BH3 mimetic drugs have been developed to bind and inhibit them. These BH3 mimetics include Navitoclax, S63845, Venetoclax, and AMG176. They induce apoptosis by releasing BH3-only proteins from the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins which consequently activate BAX and BAK to cause MOMP. Besides, pro- and anti-apoptosis protein activity can be modulated by protein-protein interaction between BCL-2 family members or various non-BCL-2 family proteins. The levels of BCL-2 family proteins are regulated at the transcriptional level by p53 and MYC to drive apoptosis in proliferative or damaged cells. Similarly, the immune cell activation transcription factors like STAT3 and NF-κB upregulate BCL-2 to support immune response and promote cell survival. These transcription factor levels are regulated in larger part by epigenetic modulation.

The bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) family members such as bromodomain-containing protein 2 (BRD2), BRD3, BRD4, and Bromodomain Testis Associated (BRDT), are epigenetic readers that recognize acetylated proteins like histones as well as transcription factors. Their function has also been implicated in RNA translation and many other roles in cell apoptosis, immune modulation, and uncontrolled proliferation. The transcriptional regulation between pro-apoptosis, anti-apoptosis, and their related transcription factors, is balanced by protein degradation through the ubiquitin-proteosome system. BRD4 exhibits superiority in inhibiting tumor growth and is overexpressed in cancer cells. It results in aberrant expression of its downstream genes and oncogenes like c-Myc and Bcl-2 in various malignancies.

Inhibitors of apoptosis (IAP) proteins negatively regulate the process of apoptosis.

3. PROTACs and anti-apoptotic proteins

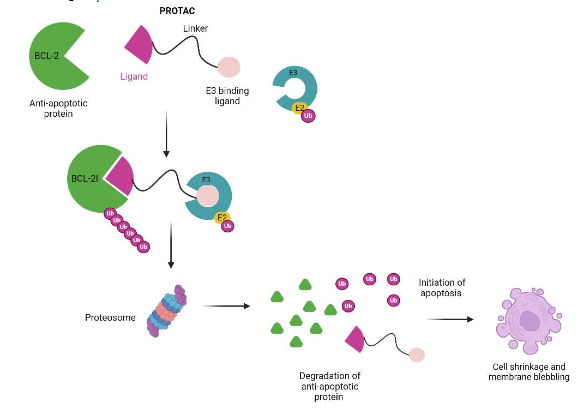

Several anti-apoptosis B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family proteins BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 are validated anticancer targets. Several PROTACs are designed to induce protein degradation using antiapoptotic IAP proteins. Here we present a review of the PROTACs with apoptosis-related proteins (BCL-2, BET and IAP) as ligands for cancer therapy and treatment.

The BCL-XL overexpression has been reported in leukemia, lymphomas, and solid tumors, and is also implicated in chemotherapy resistance in some malignancies. These anti-apoptosis proteins are extensively targeted in cancer treatment using small-molecule inhibitors. These inhibitors include BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax (ABT199), BCL-XL inhibitor A-1331852, BCL-XL/2 dual inhibitor navitoclax (ABT263), and MCL-1 inhibitor S63845. Venetoclax (ABT199) is FDA-approved for cancer treatment, but navitoclax (ABT263) inhibits BCL-XL in both tumor cells and platelets to cause on-target toxicity thrombocytopenia. BCL-XL PROTACs were developed to prevent on-target toxicity of BCL-XL inhibitors to platelets. DT2216 PROTAC is currently the most used to target BCL-XL to the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) E3 ligase. It exerts cytotoxic effects on cancer cells and spares platelets with lower levels of VHL. DT2216 consists of dual BCL-XL/2 inhibitor ABT263 linked to VHL ligand pomalidomide and several studies have shown an increase in PROTAC efficacy in cancer cells.

| BCL2 target protein | E3 ubiquitin ligase ligand | BCL2 protein inhibitor | PROTAC | Combination drug | Study model | Cancer type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCL-XL | VHL | ABT263 (dual inhibitor BCL-XL/2) | DT2216 | Sotorasib (AMG510) | H358, MIA PaCa-2 and SW837 KRASG12C-mutated cells xenografts in mice | non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), colorectal cancer, Pancreatic cancer | 40 |

| VHL | ABT263 | DT2216 | Gemcitabine | G-68 cells xenografts into NSG mice, PDXs | mouse model | Pancreatic cancer | 41 |

| VHL | ABT263 | PZ703b | Mivebresib (BET inhibitor ABBV-075) | Human bladder cancer cell lines | Bladder cancer | 45 | |

| VHL | ABT263 | DT2216 | Irinotecan | Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma PDXs into NSG mice | Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FLC) | 42 | |

| VHL, CRBN | ABT263 | DT2216, XZ739 | n/a | MOLT-4 cell line | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) | 46 | |

| VHL, CRBN | ABT263 | DT2216, PZ15227 | n/a | PDXs in C57BL/6, BALB/c and NSG mice | Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) | 43 | |

| VHL | ABT263 | DT2216 | Venetoclax (ABT199) | T cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) PDXs in NSG mice, MyLa cells xenografts | T cell lymphomas (TCLs) | 38 | |

| VHL | ABT263 | DT2216 | n/a | Human T-ALL cell lines | T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) | 44 | |

| CRBN | A1155463 | XZ424 | n/a | MOLT-4 cell line | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) | 47 | |

| VHL | A1155463 | PROTAC 6 | n/a | THP1 cell line | Leukemia | 48 | |

| VHL | ABT263 | DT2216 (753b epimer) | n/a | PDXs in NSG mice | Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) | 39 |

Khan et al reported a combination of synergistic effects of DT2216 with a covalent inhibitor of mutant KRASG12C sotorasib (AMG510) in mutant NSCLS, CRC, and pancreatic cancer mouse xenografts. The study showed that sotorasib induced apoptotic priming and enabled DT2216 to induce apoptosis in KRASG12C-mutated cancer cells. Pancreatic cancer gemcitabine resistance was dampened when PDX mouse models were treated with a combination of DT2216 and gemcitabine. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FLC) PDX mice tumor growth was reduced significantly when mice were treated with the combination of a topoisomerase I (TOPO1) inhibitor irinotecan and DT2216. This supports the PROTAC mechanism of action’s ability to negate chemotherapy drug resistance. Kolb et al used two BCL-XL degrading PROTACs (DT2166 and PZ15227) to target the highly BCL-XL expressing TITreg population from renal cell carcinoma (RCC). The study provides the rationale for eliminating Tregs within tumors by degrading intracellular pro-survival factors like BCL-XL to potentiate immunotherapy. Another study investigated the utility of BCL-XL targeting DT2216 combined with a selective BCL-2 inhibitor. The study reported a synergistically improved survival in the TCL PDX mouse model. After exposing T-ALL cells with varying concentrations of DT2216, Jaiswal et al found a decrease in BCL-XL degradation, although they argued it was in a few cells. The data warranted a wider clinical trial that recruits all the T-ALL subsets. The BCL-XL degraders include PZ703b which like DT2216 targets BCL-XL to VHL proteasomal degradation. When combined with mivebresib, PZ703b induced apoptosis in bladder cancer cells via the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. Other PROTACs also exhibited higher cytotoxic effects on cancer cells compared to the BCL-XL inhibitors including XZ739 on ALL cells, PZ15227 on renal cell carcinoma, XZ424 on ALL cells, and PROTAC 6 on THP1 cells.

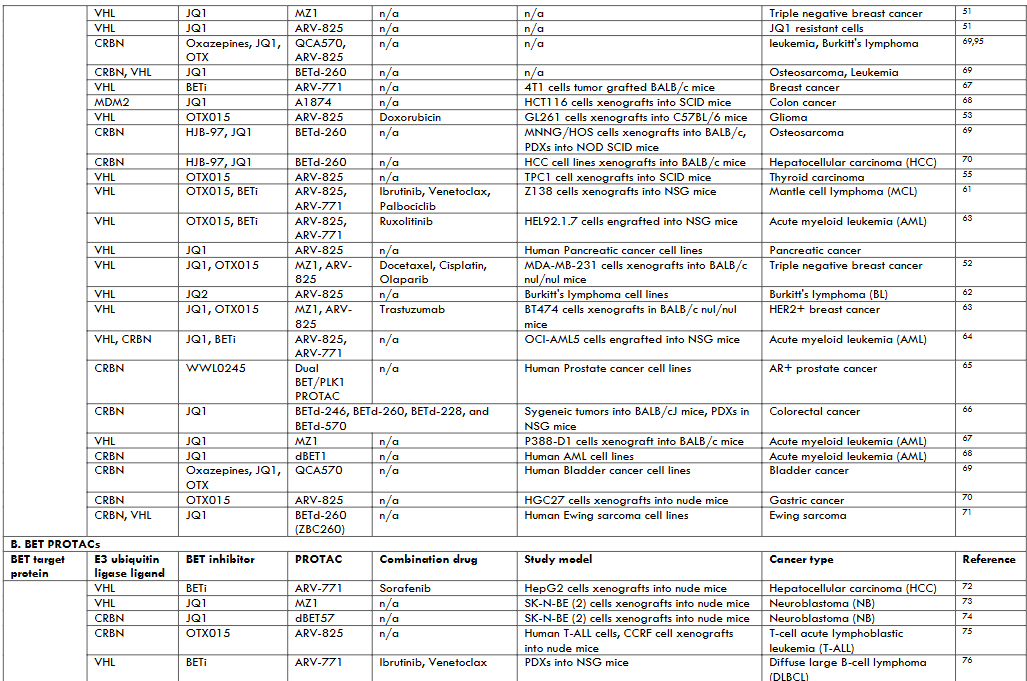

Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal (BET) Domain Proteins PROTACs BET proteins PROTACs have been largely studied in leukemia and lymphoma. Transcription factors were previously considered to be undruggable therefore, BET protein inhibitors (BETi) gave an alternative to target transcription. These inhibitors have shown antitumoral activity in hematological malignancies and solid tumors. BET PROTACs were developed to potentiate and prolong the pharmacological effect of BETi. BET PROTACs have shown increased antitumoral activity even in preclinical models that were resistant to BETi.

The BET PROTAC ARV-825 has been most widely used in cancer treatment. ARV-825 is a chimera of BETI OTX015 linked to CHL/CRBN ligands of E3 ubiquitin ligases. Two studies by He et al showed synergistic suppression of tumor growth in glioma and colorectal cancer cells by combination treatment with DOX and ARV-825 in the cRGD-P nanoparticle system. The treatment arrested the cell to G2/M phase and activated apoptosis-related pathways like caspase cascade, downregulation of Bcl-2, and upregulating Bax. ARV-825 inhibited TPC-1 xenograft tumor growth in SCID mice, human gastric cancer cells xenografts in nude mice, and T-ALL PDXs in nude mice. PROTAC ARV-825 showed antiproliferation effects and induced apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma cells, melanoma cells, pancreatic cancer cells, and Burkitt’s lymphoma cells. A combination of two BET PROTACs ARV-825 and ARV-771 (ARV-771 has a pan BETi), with a covalent inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase ibrutinib dramatically inhibited the growth and improved survival of NSG mice engrafted with ibrutinib-resistant Z138 MCL cells, and induced apoptosis in human AML cell lines. Co-treatment with ARV-825 and JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib synergistically induced a high level of apoptosis in ruxolitinib-resistant AML cells. However, Noblejas-Lopez et al reported no synergistic effects in co-treatment with PROTACs MZ1 and ARV-825 with docetaxel, cisplatin, or Olaparib, in BETi-resistant TNBC cells. Zhang et al study evaluated the antitumoral activity of PROTACs ARV-825 and ARV-763 with dexamethasone, BH3 mimetics, and Akt pathway inhibitors. The study reported that PROTACs were active against myeloma, overcame mechanisms of drug resistance, combined synergistically with conventional and novel therapeutics, and showed activity in vivo.

Other BET PROTACs investigated include ARV-771 which induced tumor cell apoptosis when combined with Raf inhibitor sorafenib on HCC cell xenografts in nude mice. This study showed that ARV-771 and sorafenib synergistically inhibited the growth of HCC cells. Co-treatment with ARV-771 and Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib or anti-apoptotic BCL2 inhibitor venetoclaxon showed synergistic lethal activity in B cell lymphoma PDXs in NSG mice. ARV-771 was derivatized to esterase cleavable maleimide linker (ECMal) and it was shown to accumulate in 4T1 tumor grafts in BALB/c mice to induce BRD4 deficiency-related apoptosis. BET PROTAC A1874 (synthesized based on BET inhibitor JQ1 and MDM2) inhibited the growth of colon cancer tumor xenografts in SCID mice by both BRD4-dependent and -independent mechanisms. BET-260 (synthesized based on BET inhibitor HJB-97) was shown to degrade BET proteins as well as triggering apoptosis in xenograft osteosarcoma tumor tissue and hepatocellular carcinoma cells PDX xenografts in BALB/c mice, Ewing sarcoma cells. PROTAC MZ1 (based on the BETi JQ1) exhibited synergistic/additive interaction with anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab in HER2+ breast tumors. The study claimed the antitumoral effect was via cell growth inhibition, downregulation of transcriptional genes, and DNA damage apoptosis. Another study by Ma et al indicated MZ1 downregulated expression of c-Myc and ANP32B genes in AML cells. PROTAC dBET1 induced broad anti-cancer effects on molecularly different AML cells.

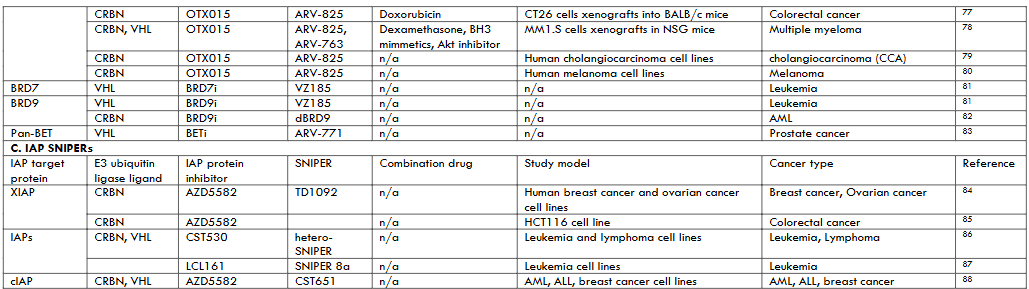

Inhibitors of Apoptosis (IAP) Proteins PROTACs In this review article, SNIPERs are treated as a subgroup of PROTACs which induce protein degradation through IAPs. IAPs interact with caspases via BIR domain to dampen apoptosis. Also, inhibitors of IAPs are designed to interact with BIR domain to both block apoptosis inhibitory activity of IAPs and induce auto-ubiquitylation and degradation IAPs. Human beings have eight IAPs (XIAP1, cIAP1/2, ML-IAP, ILP2, Survivin, NAIP, and BRUCE), of which XIAP1, cIAP1/2 exhibit E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, on which SNIPERs induce degradation. The binding of SNIPER to cIAP rapidly induces cIAP degradation, but XIAP degradation requires XIAP-SNIPER-target protein ternary complex formation. Therefore, both XIAP and target protein are simultaneously ubiquitylated only if they interact and induce XIP conformational changes to expose its lysine to E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes.

There is reported aberrant expression of cIAP1/2 and XIAP with a concomitant increase in drug resistance, and their downregulation sensitizes cancer cells to apoptosis. Currently, clinical development of several antagonists that inhibit IAP functions is underway. TD01092 is a IAP-cereblon SNIPER consisting of the SMAC mimetic AZD5582 as cIAP1/2/XIAP ligand and thalidomide as cereblon ligand. The study showed that SNIPER inhibited breast and ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion leading to cellular apoptosis. Additionally, the SNIPER reduced tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα)-induced innate immune response. Ng et al designed heterobifunctional SNIPERs by either linking VH298 (VHL ligand) or pomalidomide (CRBN ligand) to CST530 (IAP ligand). The SNIPER treatment led to potent, rapid, and preferential depletion of lymphoma and leukemia cellular IAPs including XIAP knockdown, which is rarely observed for monovalent and homo-bivalent IAP inhibitors. Another study by Steinebach et al combined a SNIPER CST651 (consisting of IAP ligand and VHL ligand) with CDK6-specific VHL targeting PROTACs (YKL-06-102 and BSJ-03-123) on leukemia and breast cancer cells. The study results showed that IAP-based PROTACs degraded both CDK4/6 and IAPs resulting in synergistic suppression of cancer cell growth. A monovalent SNIPER 8a which utilized the LCL161 IAP ligand efficiently degraded BCL-XL in malignant T-cell lymphoma cell line MyLa-1929.

4. Conclusion

The antibodies or small molecule enzyme inhibitors such as kinase inhibitors induce their effects by binding and occupying the target protein’s active site. This mechanism of action is prone to drug resistance. Also, they target only 25%-30% of known cellular proteins for clinical application. The remaining 70%-75% of genome proteins so-called “undruggable” consist of scaffolding proteins, transcription factors, cofactors, and other non-enzymatic proteins, which can be targeted for degradation with PROTACs. The event-driven mechanism of action involved in the PROTACs offers several benefits including; being catalytic, having high potency for longer, versatile target space, active at lower dose and frequency, high selectivity, active in drug resistance disease, and target nonenzymatic functions.

PROTACs are chimeric compounds consisting of a target ligand, an E3 ubiquitin ligase ligand, and a linker. For a ligand to be incorporated in a PROTAC, it requires only to bind the target protein. Therefore, ligands with no or insufficient inhibitory activity or bind any of the multiple domains of the target protein can be used. This technology is used to circumvent drug resistance by targeting different domains in oncogenic kinases since resistance to kinase inhibitors is often attributed to mutations in the kinase domain. Furthermore, nucleic acids and peptides are used as target protein ligands. More E3 ubiquitin ligases should be added to the three currently used PROTACs (VHL, CRBN, and IAP) since there are more than 600 cellular E3 ubiquitin ligases. Also, it is paramount to investigate whether these E3s are differentially expressed in different tissues or malignancies. In addition, hetero-PROTACs that combine different E3s have shown superior target protein degradation compared to their monovalent E3s PROTACs. The PROTAC degradation activity, pharmacological properties, and stability are determined by the chemical and physiological aspects of the linker used. Similarly, the selection of proteins that play a major oncogenic role in specific malignancies is paramount.

PROTACs have been used successfully to reduce oncoproteins in cancer therapy. However, their use in clinical studies is strained by several limitations. Due to their complex structure usually with high molecular weight, PROTACs have poor pharmacokinetics profiles in vivo. In addition, PROTACs exert their effects by irreversibly inducing target protein degradation which can lead to higher irreversible toxicity in vivo. Similarly, PROTACs off-target proteins are degraded resulting in severe physiological consequences. As such, toxicological studies are paramount in the development of PROTACs therapies in cancer. The use of drug delivery systems like antibody-drug conjugation and nanoformulation, can improve average lipophilicity and in vitro stability. Furthermore, the PROTAC size can be resolved by combinatorial chemistry approaches.

In conclusion, more than two decades ago the concept of targeted protein degradation using a bifunctional molecule was proposed (Kenten patent 1999). PROTAC technology is a feasible and attractive approach for developing novel drugs against currently undruggable oncoproteins. In 2019, the first phase I clinical study of PROTACs was started, and more than 10 clinical trial studies followed shortly. By January 2025, an ongoing study was recruiting participants to investigate the effects of DT2216 in relapsed or refractory solid tumors and fibrolamellar carcinoma treatment. More clinical studies are required to support this promising technology.

Materials and Methods

In the current review, we included published material on PROTACs targeting antiapoptotic family proteins and have or are currently being used for cancer therapy. The antiapoptotic family proteins researched and reported were BET, BCL2, and IAP. A bibliographic search was carried out in PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 12 April 2024), Web of Science (www.webofscience.com (accessed on 12 April 2024), and Google Scholar citation (www.scholar.google.com (accessed on 12 April 2024). References were searched using the following terms: protac* AND cancer AND apoptosis AND BCL/BET/IAP/MCL1. Data and inferences from 47 published articles were synthesized and included in this review as shown in figure 4.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cancer Statistics – NCI. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/statistics (2015).

- Lee, Y. T., Tan, Y. J. & Oon, C. E. Molecular targeted therapy: Treating cancer with specificity. European journal of pharmacology 834, 188–196 (2018).

- Shawver, L. K., Slamon, D. & Ullrich, A. Smart drugs: tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Cancer cell 1, 117–123 (2002).

- Finan, C. et al. The druggable genome and support for target identification and validation in drug development. Science translational medicine 9, eaag1166 (2017).

- Zhao, L., Zhao, J., Zhong, K., Tong, A. & Jia, D. Targeted protein degradation: mechanisms, strategies and application. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 7, 113 (2022).

- Li, R. et al. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) in cancer therapy: present and future. Molecules 27, 8828 (2022).

- Yim, W. W.-Y. & Mizushima, N. Lysosome biology in autophagy. Cell discovery 6, 6 (2020).

- Zengerle, M., Chan, K.-H. & Ciulli, A. Selective small molecule induced degradation of the BET bromodomain protein BRD4. ACS chemical biology 10, 1770–1777 (2015).

- Wang, S., He, F., Tian, C. & Sun, A. From PROTAC to TPD: Advances and Opportunities in Targeted Protein Degradation. Pharmaceuticals 17, 100 (2024).

- Naito, M., Ohoka, N. & Shibata, N. SNIPERs—Hijacking IAP activity to induce protein degradation. Drug Discovery Today: Technologies 31, 35–42 (2019).

- Nishimura, K., Fukagawa, T., Takisawa, H., Kakimoto, T. & Kanemaki, M. An auxin-based degron system for the rapid depletion of proteins in nonplant cells. Nature methods 6, 917–922 (2009).

- Buckley, D. L. & Crews, C. M. Small-Molecule Control of Intracellular Protein Levels through Modulation of the Ubiquitin Proteasome System. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 53, 2312–2330 (2014).

- Ohoka, N. et al. Derivatization of inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) ligands yields improved inducers of estrogen receptor α degradation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 293, 6776–6790 (2018).

- Liu, J. et al. PROTACs: a novel strategy for cancer therapy. in Seminars in Cancer Biology vol. 67 171–179 (Elsevier, 2020).

- Ito, T. Protein degraders-from thalidomide to new PROTACs. The Journal of Biochemistry mvad113 (2023).

- Singh, R., Letai, A. & Sarosiek, K. Regulation of apoptosis in health and disease: the balancing act of BCL-2 family proteins. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 20, 175–193 (2019).

- Ke, F. F. et al. Embryogenesis and adult life in the absence of intrinsic apoptosis effectors BAX, BAK, and BOK. Cell 173, 1217–1230 (2018).

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer discovery 12, 31–46 (2022).

- Yap, J. L., Chen, L., Lanning, M. E. & Fletcher, S. Expanding the cancer arsenal with targeted therapies: Disarmament of the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins by small molecules: Miniperspective. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 60, 821–838 (2017).

- Brahmbhatt, H., Oppermann, S., Osterlund, E. J., Leber, B. & Andrews, D. W. Molecular pathways: leveraging the BCL-2 interactome to kill cancer cells—mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Clinical Cancer Research 21, 2671–2676 (2015).

- Lopez, A. et al. Co-targeting of BAX and BCL-XL proteins broadly overcomes resistance to apoptosis in cancer. Nature communications 13, 1199 (2022).

- Kotschy, A. et al. The MCL1 inhibitor S63845 is tolerable and effective in diverse cancer models. Nature 538, 477–482 (2016).

- Kale, J., Osterlund, E. J. & Andrews, D. W. BCL-2 family proteins: changing partners in the dance towards death. Cell Death & Differentiation 25, 65–80 (2018).

- Mitchell, K. O. et al. Bax is a transcriptional target and mediator of c-myc-induced apoptosis. Cancer research 60, 6318–6325 (2000).

- Grossmann, M. et al. The anti-apoptotic activities of Rel and RelA required during B-cell maturation involve the regulation of Bcl-2 expression. The EMBO journal 19, 6351–6360 (2000).

- Roe, J.-S., Mercan, F., Rivera, K., Pappin, D. J. & Vakoc, C. R. BET bromodomain inhibition suppresses the function of hematopoietic transcription factors in acute myeloid leukemia. Molecular cell 58, 1028–1039 (2015).

- Wang, N., Wu, R., Tang, D. & Kang, R. The BET family in immunity and disease. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 6, 23 (2021).

- Yang, H., Wei, L., Xun, Y., Yang, A. & You, H. BRD4: An emerging prospective therapeutic target in glioma. Molecular Therapy-Oncolytics 21, 1–14 (2021).

- Silke, J. & Meier, P. Inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins–modulators of cell death and inflammation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 5, a008730 (2013).

- Vogler, M. Targeting BCL2-proteins for the treatment of solid tumours. Advances in medicine 2014, (2014).

- Ng, Y. L. D. et al. Heterobifunctional Ligase Recruiters Enable pan-Degradation of Inhibitor of Apoptosis Proteins. J Med Chem 66, 4703–4733 (2023).

- Zhang, X. et al. Discovery of IAP-recruiting BCL-XL PROTACs as potent degraders across multiple cancer cell lines. Eur J Med Chem 199, 112397 (2020).