Osteosarcoma Diagnosis: Challenges and Clinical Insights

Osteosarcoma or Not: Diagnostic Challenges, Differentials and a few Clinical Cases

Athena L. Etzioni1

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 December 2022

CITATION Etzioni, A.L. 2024. Osteosarcoma or Not: Diagnostic Challenges, Differentials and a few Clinical Cases. Medical Research Archives, [online] 12(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i2.4031

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Osteosarcoma, a mesenchymal tumor, arises from proliferation of malignant osteoblasts. It is important to observe clinical history, perform a thorough physical examination, and complete appropriate diagnostic testing to differentiate osteosarcoma from other conditions; whether neoplastic, trauma-induced or inflammatory in nature with similar compiled information and background. Cytology may serve as a screening tool to determine whether a swelling represents a neoplastic lesion or an inflammatory process. Benign processes may include inflammatory lesions such as an abscess; reactive conditions, such as hypersensitivity reactions; hematomas or seromas. Neoplastic conditions may also be benign, such as cysts, fibromas or adenomas or may be malignant. Malignant conditions may include, but are not limited to soft tissue sarcomas, fibrosarcomas or other sarcomas, adenocarcinomas or mast cell tumors, for example. Histopathology is generally considered the gold standard for determining the definitive diagnosis of a swelling. Additional diagnostics, such as immunohistochemistry, special staining, flow cytometry and PARR may be explored. The latter two diagnostics are especially useful to evaluate lymphoid neoplasia, whether lymphoma or leukemia. The goal of this manuscript is to discuss osteosarcoma, elucidate differentials that may appear cytologically similar and to briefly mention diagnostic tools that may help to arrive at a definitive diagnosis, as well as to rule out other causes of similar findings.

Introduction

One-Health is important for everyone and everything. This means the health of humans, animals, and the environment. Many of the diseases and other types of ailments that humans suffer with are also diagnosed in dogs, cats and other species of animals. Environmental challenges have and still include control of waste production from humans and industrial factories. Pollution has been linked to the increased occurrence of certain types of cancers, including those of bone (García-Pérez et al., 2021), liver (Gant et al., 2023), breast and have been recognized in humans (Robinson and Zamora, 2021) and in animals, including marine life (Baines et al., 2022). Increased incidence of bone cancer has been reported in both the human and veterinary literature, and it is important to provide background information, clinical signs, and diagnostic testing for infectious agents (García-Pérez et al., 2021; Mitchell et al., 2021). The aim of this paper is to provide background information on osteosarcoma, a mesenchymal tumor, arising from proliferation of malignant osteoblasts. It is important to observe clinical history, perform a thorough physical examination, and complete appropriate diagnostic testing to differentiate osteosarcoma from other conditions; whether neoplastic or non-neoplastic.

Background

Cancer, malignant neoplasia, may occur in any aged individuals (Withrow and Vail, 2007). There are leukemias (Evans, 2022) and embryonic tumors that may be found in newborn babies and animals alike (Withrow and Vail, 2007). Osteosarcomas occur in pediatric patients (Gadwal et al., 2001; Simpson and Brown, 2018), but are more commonly diagnosed in older dogs (Pool, 2022).

In cases of bony lesions, fractures may be more common than neoplastic. However, it is important to embrace various diagnostic modalities to definitively determine the underlying cause of lameness. In dogs and humans, it has been determined that fracture fixation devices have served as a nidus for development of osteosarcoma (Sinibaldi et al., 1976; Harrison et al., 1976; Etzioni, 2022; Withrow and Vail, 2007).

Also of note are that certain parasites, such as Spirocerca lupi, can cause lesions that may develop into osteosarcoma (Withrow and Vail, 2007). It is important to thoroughly examine each case and perform appropriate diagnostic and complementary testing to then arrive at a definitive diagnosis, to instill the proper treatment. This manuscript will highlight a few osteosarcoma cases, briefly discuss some differential diagnoses that could appear similar, and discuss diagnostics that aid in definitive determination of osteosarcoma.

Origin

Osteosarcoma is a malignant mesenchymal tumor of bone, arising from the proliferation of malignant osteoblasts. It is the most common bone tumor and may originate from long bones in the limbs, vertebrae and ribs in dogs. Having the affliction may result in lameness, especially when involving long bones.

“Away from the elbow and toward the knee” is a generalization for the usual distribution of this neoplastic process. However, these tumors may also occur in soft tissues, such as mammary glands. It is unknown why extraskeletal or extraosseous osteosarcomas occur. Most extraskeletal osteosarcomas occur in the soft tissues of humans and visceral organs of dogs (Patnaik, 1990; Makielski, 2019).

Whether these tumors, when occurring in the mammary gland, are associated with spay/neuter status is unknown. Although there are associations of sex (humans and animals), spay/neuter status (for animals), and breed (for animals) (Dhein et al., 2024). Mixed mammary tumors, whether benign or malignant forms, may contain bone elements; thus, variable osteoclasts, osteoblasts and even bone matrix may be identified on cytology and histopathology (Cassali et al., 2012).

There are many studies associating a more frequent occurrence of mammary carcinomas and mixed mammary tumors in intact dogs and those spayed after the first estrous cycle. It is noteworthy that intact dogs, whether male or female, are at an increased risk for development of mammary gland tumors. They can be malignant, with osteosarcoma being among the differential diagnoses.

Diagnosis

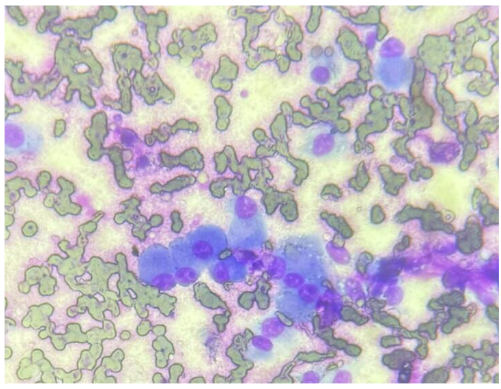

Diagnostics may include immunohistochemistry, special staining for ALP activity, flow cytometry and PARR. The latter two diagnostics are especially useful to evaluate lymphoid neoplasia, whether lymphoma or leukemia. In contrast to some mesenchymal cells, osteoblasts (the cell of origin for osteosarcoma) tend to exfoliate well (Fig. 1).

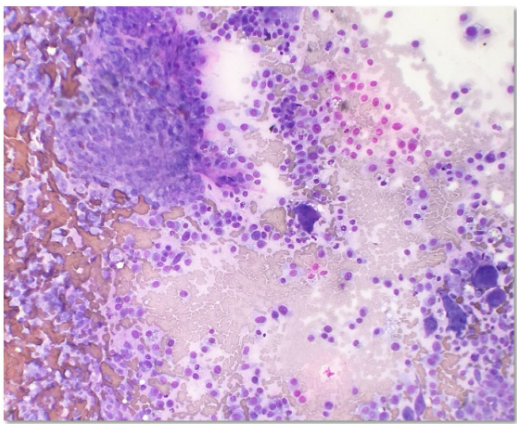

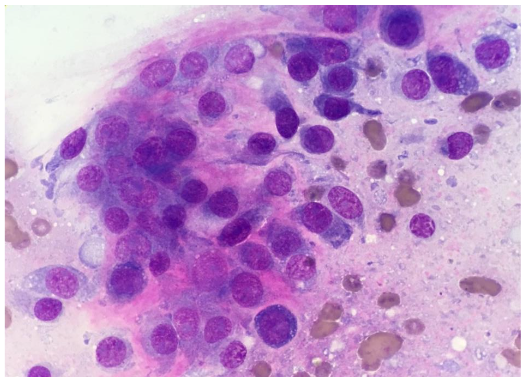

Classic cytologic descriptions of osteosarcomas may include moderate to high numbers of plump mesenchymal cells in a densely granular eosinophilic background with varying amounts of an extracellular pink wavy or amorphous matrix material in association with the neoplastic cells (Raskin and Meyer, 2016; Etzioni, 2022). Individual neoplastic cells are oval to rounded with moderately basophilic cytoplasm, with/without a perinuclear clearing/Golgi zone and flecks of atypical mitotic figures may be observed in some neoplastic and multinucleate cells. Nuclei are extremely eccentric, often appearing as if in the center of the cell, and are usually one to two prominent nucleoli.

To investigate the course of disease in patients, whether they are human or animal, diagnostic testing is necessary. Testing may include, but are not limited to diagnostic imaging, hematology, clinical chemistry, urinalysis, fecal skin testing, PCR or serological testing for infectious agents. Discussion of the subtypes (Cagle et al., 2024) and metastatic nature of osteosarcoma (Regan et al., 2022) are beyond the scope of this paper.

Clinical Presentation

This neoplastic condition, osteosarcoma, amongst other causes of lameness, require diagnostic testing to elucidate. When lameness presents, diagnostic imaging is a common recommendation to pinpoint if the bone is affected by fracture, lysis or proliferative lesions (Cheverko, 2017). This may also show, especially with digital radiography, increased densities of soft tissues associated with inflammatory lesions, especially of the muscles. These inflammatory lesions may be of infectious or noninfectious causes. Osteoarthritis, synovitis, autoimmune joint disease, cruciate or meniscal tears are also differentials for lameness. With inflammatory lesions, peripheral blood evaluation for white blood cell counts, fine needle aspirate and subsequent cytologic and chemical assessment of synovial fluid are necessary.

Case 1

12-year-old, intact male, Collie dog that presented with a right hind limb lameness. Pain therapy was initiated immediately. This patient had a radiographic examination performed, which revealed a large osteolytic lesion in the distal femur. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy was performed and deposited into formalin and processed for a routine histopathology sample. An initial pre-Wright-stained cytology smear was stained alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity positive with the special stain, although tretrazolium/5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (NBT/BCIP) (Thermo Scientific), (Raskin and Meyer, 2016; Aguino, 2018; Etzioni, 2022; Nehlhaus et al., 2011; Cagle et al., 2024). Additionally, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and flow cytometry (CD18) were performed to support the interpretation of neoplasia however, the findings were inconclusive.

Case 2

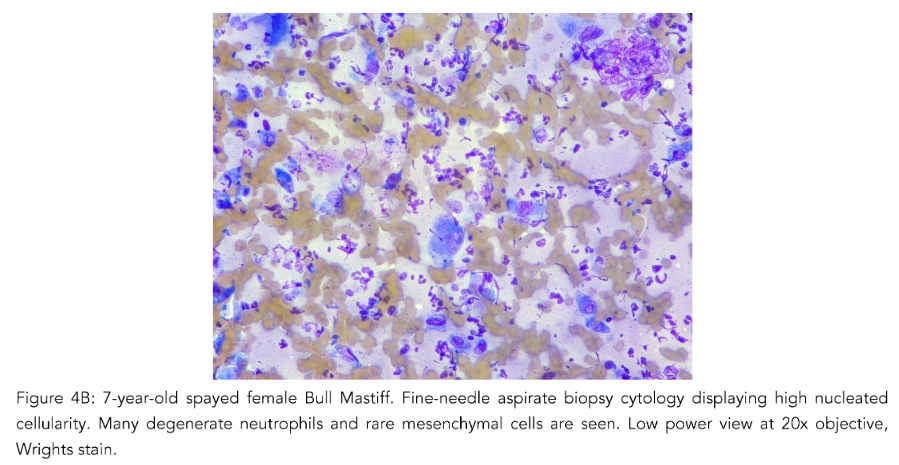

7-year-old, spayed female, Bull Mastiff with a distal tibial bony lesion (Fig. 3). She had an intermittent toe touching lameness of the right hindlimb. Initially, bone biopsies with histopathology were performed to only arrive at reactive bone (Fig. 3, blue arrow). This case drives home that if the tissue sampled does not encompass the root cause or nidus, the definitive diagnosis may be missed.

Caveats

Case 2 (Fig. 3) demonstrates the difficulties of getting a diagnostic sample. Employing multiple diagnostic tools were useful to overcome this limitation. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy requires quick execution for diagnostic material to be obtained. The interpretation of neoplasia may be diminished when cells are diluted in extraction from tissue easily derived in spreading them onto a glass slide. The nuclei can easily fall or collapse into the background, leading to an inaccurate diagnosis.

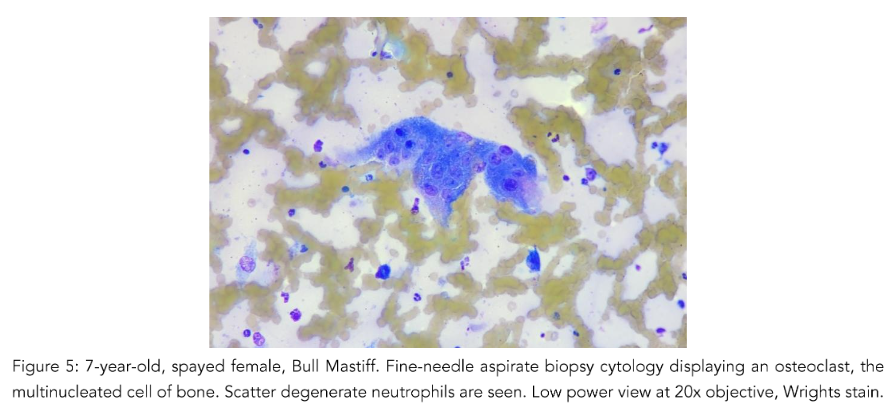

Osteoclasts

The presence of osteoclasts must also be considered. When osteoclasts (Fig. 5) are seen, indicates bony lysis is likely occurring. However, bony lysis may occur in neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions. With inflammation of the bone, lysis may occur. Thus, seeing this cell type does not constitute a diagnosis of neoplasia. Since osteoclasts are charged with cleaning up bone, variable numbers of them may be seen in osteosarcomas, mixed mammary tumors and osteomyelitis. They may also be a part of the process of remodeling bone during fracture healing and during normal growth in animals and humans. Additionally, giant cells may be mistaken for osteoclasts and may be a feature of feline and less commonly canine osteosarcomas cytologically and histopathologically (Pool, 1978).

Case 3

7-year-old, spayed female, Bull Mastiff, plain lateral radiograph of the right femur where a bony reactive lesion (white arrows). Subsequent to this, fine-needle aspirate biopsy was performed and cytology was performed to confirm a diagnosis of osteosarcoma.

Case 4

5-year-old, intact male, Bulldog that presented for a left front limb lameness, which by plain radiographs was centered at the shoulder joint. This patient was managed with supportive therapy, which included minimal exercise, pain and anti-inflammatory medications. When presenting to the teaching hospital at Tuskegee University repeat survey radiography and fine needle aspiration were performed. With an interpretation of osteosarcoma likely, the patient was humanely euthanized. The lesion was not further biopsied with histopathology due to the extensiveness of the lesion and inability to completely surgically remove the tumor.

Discussion

Osteosarcoma is one of the most common bone tumors in both humans and animals. It is the most common bone tumor in both species (Raskin and Meyer, 2016). In veterinary medicine, we may have a limited ability to perform diagnostic tests. A definitive diagnosis may require these tests in succession or in tandem (Raskin and Meyer, 2016). In veterinary medicine, we may also not always have the laboratory testing readily available. This can be a limiting factor to the diagnosis of osteosarcoma. However, when the patient has osteosarcoma, the clinical signs may be similar to other conditions, often eliciting clinical signs of pain and medications. With inflammatory lesions some neoplasms may complicate the clinical signs. Understanding of the disease process their pet may be afflicted with, can allow an informed decision.

There is no conflict of interest.

There is no funding statement.

There are no acknowledgements.

The ORCID Number is https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1363-8957.

References

2. García-Pérez, J, Morales-Piga, A, Gómez-Barroso, et al. Risk of bone tumors in children and residential proximity to industrial and urban areas: New findings from a case-control study. Sci Total Environ, 2017; 579: 1333-1342. doi.org/10.1016/j. scitotenv.2016.11.131

3. Makielski KM, Mills LJ, Sarver AL, et al. Risk Factors for Development of Canine and Human Osteosarcoma: A Comparative Review. Vet Sci. 2019; 6(2):48. Published 2019 May 25. doi:10.3390 /vetsci6020048

4. Evans SJM. Flow Cytometry in Veterinary Practice. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2023;53(1): 89-100. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2022.07.008

5. Robinson D. Cancer clusters: findings vs feelings. MedGenMed. 2002;4(4):16. Published 2002 Nov 6.

6. Sinibaldi K, Rosen H, Liu SK, DeAngelis M. Tumors associated with metallic implants in animals. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;(118):257-266.

7. Harrison JW, McLain DL, Hohn RB, Wilson GP 3rd, Chalman JA, MacGowan KN. Osteosarcoma associated with metallic implants. Report of two cases in dogs. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976; (116):253-257.

8. Dantas Cassali G, Cavalheiro Bertagnolli A, Ferreira E, Araújo Damasceno K, de Oliveira Gamba C, Bonolo de Campos C. Canine mammary mixed tumours: a review. Vet Med Int. 2012;2012: 274608. doi: 10.1155/2012/274608. Epub 2012 Oct 21. PMID: 23193497; PMCID: PMC3485544.

9. Mitchell PD, Dittmar JM, Mulder B, et al. The prevalence of cancer in Britain before industrialization. Cancer. 2021;127(17):3054-3059. doi:10.1002/cncr.33615

10. Gadwal SR, Gannon FH, Fanburg-Smith JC, Becoskie EM, Thompson LD. Primary osteosarcoma of the head and neck in pediatric patients: a clinicopathologic study of 22 cases with a review of the literature. Cancer. 2001;91(3):598-605.

11. Etzioni AL. Osteosarcoma diagnosed in a dog using a formalin-fixed fine-needle aspirate biopsy. Vet Clin Pathol. 2022;51:349-355. doi: 10.1111/ vcp.13056

12. Cheverko CM, Bartelink EJ. Resource intensification and osteoarthritis patterns: changes in activity in the prehistoric Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta region. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2017; 164(2):331-342. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23272

13. Patnaik AK. Canine extraskeletal osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases. Vet Pathol. 1990;27(1):46-55. doi:10.117 7/030098589002700107

14. Simpson E, Brown HL. Understanding osteosarcomas. JAAPA. 2018;31(8):15-19. doi:10.1 097/01.JAA.0000541477.24116.8d

15. Regan DP, Chow L, Das S, et al. Losartan Blocks Osteosarcoma-Elicited Monocyte Recruitment, and Combined With the Kinase Inhibitor Toceranib, Exerts Significant Clinical Benefit in Canine Metastatic Osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2022; 28(4):662-676. doi:10.1158/10 78-0432.CCR-21-2105

16. Agustina H, Asyifa I, Aziz A, Hernowo BS. The Role of Osteocalcin and Alkaline Phosphatase Immunohistochemistry in Osteosarcoma Diagnosis. Patholog Res Int. 2018;2018:6346409. Published 2018 May 3. doi:10.1155/2018/6346409

17. Raskin, RE. Meyer DJ. Canine and Feline Cytology: A Color Atlas and Interpretation Guide. 3rd Ed. Elsevier, Inc. St. Louis, Missouri, 2016, PAGES.

18. Withrow SJ, Vail DM. Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 4th Ed. Saunders and Elsevier. St. Louis, Missouri. 2007, PAGES.

19. Cagle LA, Maisel M, Conrado FO, et al. Telangiectatic osteosarcoma in four dogs: Cytologic, histopathologic, cytochemical, and immunohistochemical findings. Vet Clin Pathol. 2024;53(1):85-92. doi:10.1111/vcp.13338

20. Neihaus SA, Locke JE, Barger AM, et al. A novel method of core compared to for J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2011;47:317-23.

21. Gan T, Bambrick H, Tong S, Hu W. Air pollution and liver cancer: A systematic review. J Environ Sci (China). 2023 Apr;126:817-826. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2022.05.037. Epub 2022 Jun 2. PMID: 36503807.

22. Baines C, Lerebours A, Thomas F, Fort J, Kreitsberg R, Gentes S, Meitern R, Saks L, Ujvari B, Giraudeau M, Sepp T. Linking pollution and cancer in aquatic environments: A review. Environ Int. 2021 Apr;149:106391. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021. 106391. Epub 2021 Jan 27. PMID: 33515955.

23. Pool RR. Tumors of Bone and Cartilage. In: Moulton, editor. Tumors in Domestic Animals. Univ. California Press; Berkeley: 1978. pp. 89–149.

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1363-8957

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1363-8957