Cost-Effectiveness of Gene Therapy for Hemophilia B

Cost-effectiveness of gene therapy with etranacogene dezaparvovec versus factor IX prophylaxis in men with hemophilia B in Brazil

Aline Alves Teodósio1, Ana Clara Silva Mendes1, Ricardo Mesquita Camelo1,2, Augusto Afons Guerra Júnior1, Francisco de Assis Acurcio1*

- Faculdade de Farmácia, CCATES, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil.

- Faculdade de Farmácia, CCATES, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil; Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 January 2025

CITATION: Teodósio, A. A., Mendes, A. C. S., Camelo, R. M., Guerra Júnior, A. A., & Acurcio, F. A. (2025). Cost-effectiveness of gene therapy with etranacogene dezaparvovec versus factor IX prophylaxis in men with hemophilia B in Brazil. European Society of Medicine.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6167

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Background: The high costs and uncertainties surrounding the effectiveness and safety of new health technologies necessitate continuous evaluation to balance access and sustainability within Brazil’s Unified Health System.

Aims: Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing etranacogene dezaparvovec versus factor IX prophylaxis in people with hemophilia B from the Brazilian healthcare system perspective.

Methods: A cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted using TreeAge Pro software. A decision tree model compared the costs and effectiveness of etranacogene dezaparvovec versus factor IX prophylaxis in preventing bleeding in adult male with severe or moderately severe hemophilia B over a three-year horizon. A deterministic sensitivity analysis identified variables impacting incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Results: etranacogene dezaparvovec incurred a cost of USD 2,335,747 (BRL 10.810.993) versus USD 46,451 (BRL 232.256) for plasma-derived factor IX prophylaxis, with an incremental cost of USD 2,115,747 (BRL 10.578.737). The effectiveness (number of bleeding events) was 2.86 for etranacogene dezaparvovec and 10.95 for factor IX prophylaxis, with etranacogene dezaparvovec avoiding 8.09 additional bleeding events. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was USD 261,436 (BRL1.307.179) per bleeding event avoided. Sensitivity analysis revealed treatment duration as the most impactful variable on incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, contributing to 80% of model uncertainty.

Discussion: International studies suggest that etranacogene dezaparvovec is cost-effective and dominant in multiple contexts, particularly when compared to extended half-life recombinant factor IX (rFIX-EHL), offering greater quality-adjusted life years for people with hemophilia B at lower long-term costs. However, a lack of robust data underscores the need for ongoing monitoring and careful evaluation before incorporation by the health system. It should also be noted that high pricing of new treatments like etranacogene dezaparvovec poses challenges for Brazil’s Unified Health System sustainability and equitable access.

Introduction

You said:

Table 1 presents the parameters used in the cost-effectiveness model.

| Parameters | Prophylaxis with pdFIX | AMT-061 (min. and max.) |

|---|---|---|

| Price per infusion | 5.39 | 5.39 |

| Price of pdFIX (US$/dose) | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| Price of AMT-061 (US$/dose) | NA | 10.8 million |

| Price of AST and ALT tests (US$) | NA | 2.01 |

Table 2. Prices used in the economic model

| Parameters | Prophylaxis with pdFIX | Range (min. and max.) | AMT-061 | Range (min. and max.) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price per infusion (R$) | 5.39 | NA | 5.39 | NA | Datasus™, 2023 proc. 030602002-5 |

| Price of pdFIX (R$/IU) | 0.33 | NA | 0.33 | NA | BPS™, 2023 code 0450529 |

| Price of AMT-061 (R$/dose) | NA | NA | 10.8 million | 2–15 million | Premise |

| Price of AST and ALT tests (R$) | NA | NA | 2.01 | NA | Datasus™, 2023 |

1 US$ = 5 R$ (Reais)

min.: minimum; max.: maximum; NA: Not applicable; pdFIX: Plasma-derived factor IX; AMT-061: etranacogene dezaparvovec; IU/kg: International Unit/kilogram; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase.

™ Datasus. Departamento de Informática do SUS (Department of Informatics of the Unified Health System) – SIGTAP: Sistema de Gerenciamento da Tabela de Procedimentos, Medicamentos, Órteses, Próteses e Materiais Especiais do SUS.

*** BPS: Banco de Preços em Saúde (Health Price Database) SIASG: Sistema Integrado de Administração de Serviços Gerais.

COST-EFFECTIVENESS MODEL

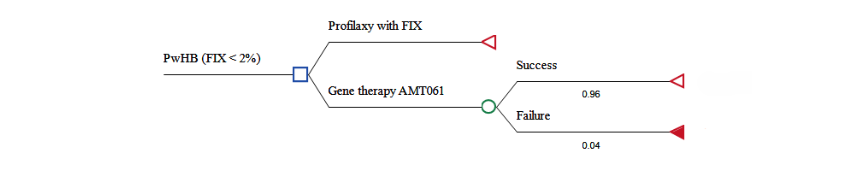

A cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted using TreeAge Pro, LLC software (Williamstown, USA). A decision tree model was developed to compare the costs and effectiveness of etranacogene dezaparvovec versus FIX prophylaxis in preventing bleeding episodes in people with hemophilia B with severe or moderately severe conditions over a three-year horizon from the perspective of the Brazilian Ministry of Health (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Decision tree of the economic cost-effectiveness analysis model of gene therapy with AMT-061 compared to prophylaxis with plasma-derived factor IX.

The modeled population consisted of adult male with hemophilia B with severe (residual FIX activity <1%) or moderately severe hemophilia (1% ≤ residual FIX activity ≤ 2%) undergoing regular FIX prophylaxis, as recommended by the World Federation of Hemophilia. This cohort aligns with participants from the HOPE-B study. The three-year time horizon was selected based on phase 2b trial data indicating a mean endogenous FIX activity of 36.9% (range: 32.3%–41.5%) three years post-treatment with etranacogene dezaparvovec. As a novel technology, data on its efficacy or effectiveness beyond this period are not yet available.

FIX prophylaxis has a variable dosage depending on the product used and the bleeding phenotype of the people with hemophilia B. Plasma-derived FIX (pdFIX) has a standard half-life of approximately 17 hours, with a dosage of 20–30 International Units (IU)/kg of body weight administered twice weekly, adjustable to individual needs. This study assumed an average dosage of 25 IU/kg twice weekly for pdFIX, with 100% adherence.

For etranacogene dezaparvovec treatment, a single-dose administration was assumed. Reapplication of etranacogene dezaparvovec was

Considered infeasible in cases of therapeutic failure due to immune responses to viral vectors or cross-immunity to other AAV-based gene therapies. People with hemophilia B experiencing significant reductions in AMT-061 expression were assumed to return to routine pdFIX prophylaxis, characterizing therapy failure.

The treatment of bleeding episodes varies based on the type of bleeding and the clinical condition of the people with hemophilia B. This model considered the dosing for hemarthrosis, the most common bleeding event. FIX dosage was calculated as: FIX IU=weight (kg)×Δ\text{FIX IU} = \text{weight (kg)} \times \Deltawhere Δ=%\Delta = \% factor needed − %\% endogenous residual factor.

To control hemarthrosis, the FIX activity increase required ranged from 30% to 80%, then the average value of 50% was adopted. Endogenous FIX levels from the HOPE-B study showed 1.19% for people with hemophilia B on FIX prophylaxis and 41.48% for those on etranacogene dezaparvovec. A median weight of 74.6 kg (IBGE, 2008) was used, resulting in treatment regimens of 49 IU/kg for pdFIX prophylaxis and 9 IU/kg for etranacogene dezaparvovec, each lasting an average of three days (Table 1).

SENSITIVITY ANALYSES

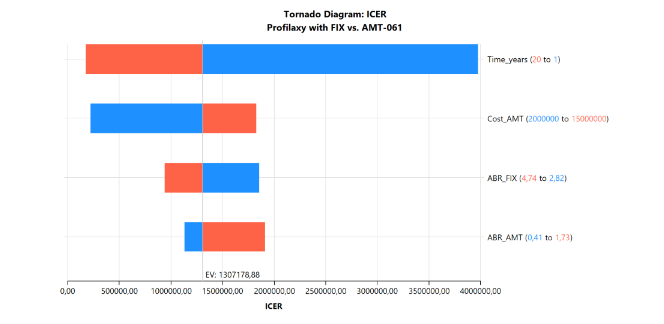

A deterministic sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess model uncertainties and identify which variables had the greatest impact on the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The ICER represents the additional cost per bleeding event avoided with etranacogene dezaparvovec. Variables analyzed included the duration of pdFIX prophylaxis, the cost of etranacogene dezaparvovec, and the annualized bleeding rates for each strategy. Minimum and maximum values for each variable (detailed in Table 1) were used. Results were illustrated using a tornado diagram. A discount rate was not applied due to the short time horizon.

Results

COST ANALYSIS:

The total cost of etranacogene dezaparvovec was US$ 2,335,747 (BRL 10,810,993), compared to US$ 46,451 (BRL 232,256) for FIX prophylaxis. This resulted in an incremental cost of US$ 2,115,747 (BRL 10,578,737) over three years.

EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS:

The number of bleeding episodes was 2.86 for etranacogene dezaparvovec and 10.95 for FIX prophylaxis, yielding an incremental benefit of 8.09 fewer bleeding events for etranacogene dezaparvovec.

INCREMENTAL COST-EFFECTIVENESS RATIO (ICER):

Etranacogene dezaparvovec demonstrated an ICER of US$ 261,436 (BRL 1,307,179) per bleeding event avoided.

SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS:

Treatment duration was the most influential variable, accounting for 80% of the uncertainty in ICER estimates (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Deterministic sensitivity analysis

Figure 2: Deterministic sensitivity analysis

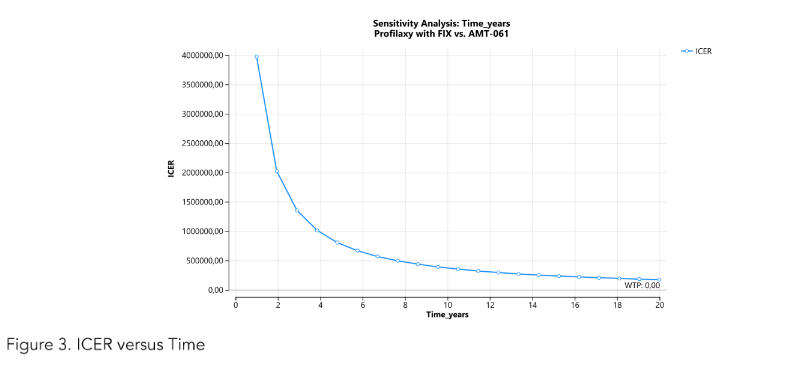

Extending the time horizon to 20 years reduced the ICER to US$ 34,400 (BRL 172,000) per bleeding event avoided (Figure 3).

Adjusting etranacogene dezaparvovec costs to US$ 400,000 (BRL 2,000,000) decreased the ICER to US$ 40,000 (BRL 200,000) per event avoided. Variations in bleeding rates had minimal impact on outcomes.

Figure 3: Cost-effectiveness analysis of etranacogene dezaparvovec.

Figure 3: Cost-effectiveness analysis of etranacogene dezaparvovec.

Discussion

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) is a multidisciplinary process that systematically evaluates the properties, effects, and impacts of health technologies. The primary goal of HTA is to inform policy and decision-making in healthcare by assessing the medical, social, economic, and ethical implications of the use of health technologies. HTA examines various dimensions of health technologies, including their clinical effectiveness, safety, cost-effectiveness, and broader social and ethical impacts. New technologies tend to be more expensive than older ones, often driving up healthcare costs. In this scenario, the HTA process ensures that new technologies are only adopted after their effectiveness has been demonstrated.

In this way, HTA is essential for balancing innovation with practical healthcare delivery. It ensures that health technologies provide value, improve patient outcomes, and promote equitable access to healthcare resources.

Through the cost-effectiveness analysis carried out in this study, etranacogene dezaparvovec reduced the annualized bleeding rate for treated bleeds by 26% compared to pdFIX prophylaxis for moderately and severely affected people with hemophilia B under the SUS perspective after three years. However, this reduction came at an additional cost of US$ 261,436 (BRL 1,307,179) per bleeding event avoided. Cost equivalency between treatments would only be achieved after 20 years of etranacogene dezaparvovec administration.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

The current study highlights several important considerations. The development of neutralizing antibodies against the vector could hinder the efficacy of gene therapy. For instance, the first gene therapy trial in people with hemophilia B, published in 2006, showed no FIX expression among participants, likely due to an immune response elicited by the AAV2 vector. Subsequent studies with AAV2/8, AAVS3, and AAV8 excluded people with hemophilia B with positive serology for these vectors.

Interestingly, AAVS does not elicit a significant immune response, making it a viable option for gene therapy in people with hemophilia B. A prior clinical trial found no correlation between pre-existing anti-AAVS antibodies and the therapeutic efficacy of etranacogene dezaparvovec in 10

People with hemophilia B. Consequently, the HOPE-B study did not select participants based on anti-AAV5 serology, and this criterion was not used in the current cost-effectiveness analysis.

Another key short-term side effect, drug-induced hepatitis, is believed to result from a cytotoxic immune response to the AAV capsid. All AAV vector-based gene therapy trials for people with hemophilia B reported some degree of asymptomatic hepatotoxicity. In certain cases, this was accompanied by a decline in FIX activity, which might or might not respond to immunomodulation with corticosteroids, typically observed within 12 weeks post-vector administration. This finding supports the use of corticosteroid-based immunomodulation of variable duration.

The recent approval of etranacogene dezaparvovec is undoubtedly a landmark achievement in the field of gene therapy. However, significant challenges remain in expanding gene therapy for hemophilia to a broader population. For example, the durability of transgene expression is a crucial factor to address.

PHARMACOECONOMIC STUDIES / COST-EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS

A recent systematic review focusing on cost-effectiveness analyses of gene therapies for hemophilia was conducted using a structured approach to evaluate the validity, relevance, and potential weaknesses of the data and assumptions in the models. The review highlights that gene therapies for hemophilia represent a major medical breakthrough, offering significant quality-of-life improvements by eliminating the need for prophylactic factor replacement therapy. However, their high costs necessitate evaluating their lifetime value to assess their impact on patients, healthcare systems, and payers. Payer concerns about the durability and magnitude of treatment effects limit access and reimbursement. Proposed solutions include outcome-based agreements and finance-based models to address high upfront costs and long-term uncertainties.

Two independent studies used cost-effectiveness analysis to compare etranacogene dezaparvovec and FIX prophylaxis for lifetime treatment. Boulos et al. developed a Markov model with microsimulation to compare etranacogene dezaparvovec with recombinant FIX prophylaxis (rFIX-MVP and rFIX-MVE) from the payer’s perspective in the U.S. Hospitalizations, surgeries, and mortality were included, with expenses estimated using a microcosting approach. The price of etranacogene dezaparvovec was $2,000,000 in the base scenario. The etranacogene dezaparvovec alternative was considered cost-effective at a threshold of US$ 150,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). In sensitivity analyses, in most scenarios, etranacogene dezaparvovec was more effective and less costly. Considering only rFIX-MVP, which has pharmacokinetics and effectiveness similar to pdFIX, the costs were US$ 15,109,058 for prophylaxis with rFIX-MVP and US$ 6,293,502 for etranacogene dezaparvovec, with QALYs of 20.95 and 23.00, respectively.

According to the results of this study, gene therapy appears more cost-effective than prophylaxis or on-demand treatment for severe hemophilia B when analyzed from a U.S. third-party payer perspective, based on clinical data, real-world costs, and assumptions where evidence was limited. With additional clinical trial data and final pricing, gene therapy could offer substantial budget savings for healthcare systems while enhancing patient outcomes and quality of life.

Meier et al. compared prophylaxis with rFIX-MVE and etranacogene dezaparvovec in a microsimulation model from the perspective of the German healthcare system. The price of etranacogene dezaparvovec was €2,000,000. The model included women, hospitalizations, surgeries, and mortality. Prophylaxis with rFIX-MVE cost €6,427,660, while etranacogene dezaparvovec cost €5,247,830. Etranacogene dezaparvovec was considered the dominant alternative. Sensitivity analysis indicated that people with hemophilia B treated with this alternative had a gain of 0.50 QALY and a cost reduction of €1,179,829 was impluenced by

The duration of maximum bleeding reduction after etranacogene dezaparvovec, the relative reduction in bleeding with rFIX-MVE prophylaxis, and the increase in bleeding over time after etranacogene dezaparvovec. The ICER was influenced by the duration of maximum bleeding reduction, relative bleeding reduction, and the increase in bleeding over time, all after etranacogene dezaparvovec. The authors concluded that depending on its price, etranacogene dezaparvovec may offer cost savings and improved health outcomes for hemophilia patients compared to extended half-life factor IX prophylaxis, positioning it as a potentially cost-effective option. However, these findings are uncertain due to limited evidence on etranacogene dezaparvovec’s long-term effectiveness.

Still in the United States, a study funded by the pharmaceutical company responsible for etranacogene dezaparvovec developed a decision-analytic model to evaluate the long-term impact of introducing etranacogene dezaparvovec for people with hemophilia B over a 20-year time horizon. Factor IX prophylaxis comparator was a weighted average of different FIX prophylaxis regimens based on US market share data. The authors compared a scenario in which etranacogene dezaparvovec is introduced in the US versus a scenario without etranacogene dezaparvovec. Adopting etranacogene dezaparvovec incurred an excess cost of US$ 265 million over the first five years but achieved annual savings starting in year 6, totaling US$ 2.58 billion by year 20. The total cumulative 20-year cost savings of $2.32 billion began accruing in year 8. Therefore, initiating people with hemophilia B on etranacogene dezaparvovec sooner can produce greater and earlier savings and additional bleeds avoided.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Recently, another gene therapy using F9-Padua with the recombinant AAV Rh74var vector was introduced to the global market. In the phase 1/2a study, 10 people with hemophilia B received gene therapy with fidanacogene elaparvovec and were followed for 52 weeks. Among the 7 people with hemophilia B who were on prophylaxis with FIX before gene therapy, FIX expression remained between 18% and 81%, and the annualized bleeding rate for treated bleeds reduced by 94%. In the phase 3 study, all 188 people with hemophilia B evaluated received FIX prophylaxis for at least 6 months before gene therapy and were followed for 15 months. The annualized bleeding rate for treated bleeds reduced by 78%, with FIX expression ranging from 2% to 119%. Corticosteroid use occurred in 28 (62%) participants due to elevated ALT or decreased FIX expression.

Additionally, other technologies are being used for treatment. In some countries, people with hemophilia B are being treated with monoclonal antibodies that inhibit the tissue factor pathway inhibitor. These medications can reduce bleeding via subcutaneous administration, while maintaining thrombin production by preventing the inactivation of the extrinsic tenase. Finally, other forms of gene therapy are still under study, such as gene editing using AAV2/6 and zinc finger nucleases. However, in this study, the only people with hemophilia B tested did not have sufficient FIX expression.

LIMITATIONS

An important limitation of this study was the time horizon considered. The duration of AMT-061 expression would not be a limiting factor, as there does not appear to be a significant reduction that would require a return to prophylaxis for at least 25.5 years. Despite this, the current study did not consider the variability in FIX expression according to characteristics of people with hemophilia B. For example, expression is higher in individuals with a higher body mass index, older age, and those who did not experience an increase in ALT.

The 3-year time frame was adopted due to the uncertainty about what could occur over longer periods, as there is no available literature. Therefore, only short-term effects could be evaluated, such as drug-induced hepatitis. However, despite hepatotoxicity screening being included in the cost-effectiveness analysis for all people with hemophilia B, the immunomodulation

Performed in some participants was not assessed. In the HOPE-B study, 9 participants received corticosteroids for 51 to 130 days, but no side effects were reported. In the long term, potential conditions such as insertion mutagenesis and musculoskeletal health should be evaluated.

Specifically regarding insertion mutagenesis, the recombinant AAV used in etranacogene dezaparvovec does not have the machinery to insert the FIX gene into the recipient’s DNA. One participant in the HOPE-B study developed hepatocellular carcinoma 12 months after treatment, but no relationship was established between etranacogene dezaparvovec and cancer. An evaluation of people with hemophilia B treated in the first gene therapy trial in 2006 over 12–15 years did not show the development of cancer. However, there are no studies with longer follow-up on gene therapy in people with hemophilia B.

Another important limitation is the lack of a national price for etranacogene dezaparvovec. In Brazil, the drug is not even in the process of being approved by ANVISA, the national regulatory agency. To conduct the current study, the price of an already incorporated gene therapy into the SUS was adopted: onasemnogene abeparvovec. However, etranacogene dezaparvovec has been described as the most expensive therapy in the world, meaning the price may be even higher than what was considered in this analysis. In the United States, in 2023, the price of etranacogene dezaparvovec was 1.6 times higher than the price of onasemnogene abeparvovec.

Furthermore, although etranacogene dezaparvovec is a new therapy with potentially high effectiveness and low risks, the comparator used in this study from the perspective of the Brazilian reality is an outdated product. Worldwide, pdFIX still represents a large portion of FIX concentrates used in the treatment of people with hemophilia B. However, in countries where hemophilia investments are intensified, rFIX is now used, with greater attention to rFIX-MVE. There is evidence that prophylaxis with rFIX-MVE is more effective in both reducing bleeds and decreasing total FIX consumption.

Finally, the study did not take into account specific treatment approaches that are required for special people with hemophilia B, such as acute on chronic liver failure due to hepatitis B, coinfection with hepatitis C or D, or human immunodeficiency virus, and hepatitis B infection in patients who are in immunosuppressive states due to specific therapies and liver transplant recipients.

Conclusions

In Brazil, the Federal Constitution guarantees all citizens the right to healthcare in a free and universal manner, establishing that access should be ensured by the State through social and economic policies. Additionally, it asserts that this State responsibility is shared with businesses and families. However, ensuring access to healthcare, especially medications, has become an increasing challenge due to the high cost of innovative technologies launched on the market. This scenario is further aggravated by uncertainties related to these technologies, stemming from initial clinical studies that often do not include comparison groups, have short follow-up periods, and use surrogate outcomes.

The cost-effectiveness analysis conducted showed that the gene therapy etranacogene dezaparvovec provides significant benefits in reducing bleeds in patients with moderate to severe hemophilia B, but it comes with high costs that are only balanced over a 20-year time horizon. Limitations such as the still restricted time horizon, which prevents the analysis of long-term side effects, and the lack of a defined national price, among others, complicate the evaluation of the technology for its potential implementation in Brazil. International studies indicate that, despite the high cost, etranacogene dezaparvovec is cost-effective and dominant in various scenarios, especially when compared to prophylaxis with extended half-life recombinant products (rFIX-MVE), offering greater QALY to people with hemophilia B and lower long-term costs. However, the lack of more robust data reinforces the need for continuous monitoring and further research. Careful evaluation before its incorporation. Additionally, the substantial pricing of innovative drugs like etranacogene dezaparvovec challenges SUS sustainability and equitable access.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

RMC received financial support as a speaker and to participate in scientific events from Bayer, NovoNordisk, Hoffman-La Roche, and Takeda, all unrelated to this study. JAT, ACSM, AAGJ, and FAA declare that there are no conflicts of interest that could influence these results.

Funding Statement:

The study did not receive financial support for its preparation, development, or publication.

Acknowledgements:

To the CCATES/UFMG team – Collaborating Center of SUS for Technology Assessment and Excellence in Health, for their support.

References

1. Sidonio RFJr, Malec L. Hemophilia B (factor IX deficiency). Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 202;35 (6):1143-1155. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2021.07.008

2. WFH World Federation of Hemophilia Report on the Annual Global Survey 2023. Montreal: WFH 2024 https://wfh.org/research-and-data-collection/annual-global-survey/

3. Philipp C. The aging patient with hemophilia: complications, comorbidities, and management issues. Hematology 2010; 2010(1):191–196. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.191.

4. Srivastava A, Santagostino E, Dougall A, et al. WFH Guidelines for the management of hemophilia, III edition Haemophilia. 2020:26(Suppl 6): 1-158. doi: 10.1111/hae.14046.

5. Rezende SM, Neumann I, Angchaisuksiri P, et al. International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis clinical practice guideline for treatment of congenital hemophilia A and B based on the grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation methodology. J. Thromb. Haemost, 2024;22(9);2629–2652. doi: 10.1016/j.jtha.2024.05.026.

6. Manco-Johnson MJ, Abshire TC, Shapiro AD, et al. Prophylaxis versus episodic treatment to prevent joint disease in boys with severe hemophilia. N Engl J Med 2007; 357(6):535-544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067659.

7. Acharya SS. Advances in hemophilia and the role of current and emerging prophylaxis. Am J Manag Care 2016;22(5-Suppl):s116-125. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27266808/

8. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Especializada e Temática. Coordenação-Geral de Sangue e Hemoderivados. Manual de hemofilia (Guide on the management of hemophilia). Brasília; Ministério da Saúde; II ed; 2015. 79 p.

9. Torres-Ortuño A. Adherence to prophylactic treatment. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2019;30(1S Suppl 1):S19-S21. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000822.

10. Iorio A, Fischer K, Blanchette V,et al. Tailoring treatment of haemophilia B: accounting for the distribution and clearance of standard and extended half-life FIX concentrates. Thromb Haemost. 2017; 117(6):1023-1030. doi: 10.1160/TH16-12-0942.

11. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovação e Insumos Estratégicos em Saúde. Departamento de Assistência Farmacêutica e Insumos Estratégicos. Relação nacional de medicamentos essenciais [National relation of essential medicines] Rename 2022. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde,2022.181p. Available at: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/relacao_nacional_medicamentos_2022.pdf

12. Samelson-Jones BJ, George LA. Adeno-associated virus gene therapy for hemophilia. Annu Rev Med. 2023;74:231-247. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-043021-033013

13. Manno CS, Pierce GF, Arruda VR, et al. Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat Med. 2006;12(3):342-347. doi: 10.1038/nm1358. Erratum in: Nat Med. 2006; 12(5):592. Rasko, John [corrected to Rasko, John JE]; Rustagi, Pradip K [added].

14. Dhillon S. Fidanacogene elaparvovec: first approval. Drugs. 2024; 84(4):479-486. doi: 10.1007/s40265-024-02017-4. Epub 2024 Mar 12. PMID: 38472707.

15. Heo YA. Etranacogene dezaparvovec: first approval. Drugs. 2023;83(4):347-352. doi: 10.1007 /s40265-023-01845-0.

16. Miesbach W, Meijer K, Coppens M, et al. Gene therapy with adeno-associated virus vector 5-human factor IX in adults with hemophilia B. Blood. 2018; 131(9):1022-1031. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-804419.

17. von Drygalski A, Gomez E, Giermasz A, et al. Stable and durable factor IX levels in patients with hemophilia B over 3 years after etranacogene dezaparvovec gene therapy. Blood Adv. 2023;7(19 ):5671–5679. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.202200888649

18. Majowicz A, Nijmeijer B, Lampen MH, et al. Therapeutic hFIX activity achieved after single AAV5-hfix treatment in hemophilia B patients and NHPs with pre-existing anti-AAV5 NABs. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2019;14:27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtm.2019.05.009.

19. VandenDriessche T, Chuah MK. Hyperactive factor IX Padua: a game-changer for hemophilia gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2018;26(1):14-16. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.12.007

20. Simioni P, Tormene D, Tognin G, et al. X-Linked thrombophilia with a mutant factor IX (factor IX Padua). N Engl J Med. 2009;361(17):1671–1675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904377.

21. Pipe SW, Leebeek FWG, Recht M, et al. Gene therapy with etranacogene dezaparvovec for hemophilia B N Engl J Med. 2023;388(8):706–718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2211644.

22. CSL Behring. LLC. HEMGENIX ® (etranacogene dezaparvovec-drlb) suspension, for intravenous infusion 2023. chrome-extension: //efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://labeling.cslbehring.com/PI/US/Hemgenix/EN/Hemgenix-Prescribing-Information.pdf

23. Blair HA. Onasemnogene Abeparvovec: a review in spinal muscular atrophy. CNS Drugs. 2022; 36 (9):995-1005. doi: 10.1007/s40263-022-00941-1.

24. von Drygalski A, Giermasz A, Castaman G, et al. Etranacogene dezaparvovec (AMT-061 phase 2b): normal/near normal FIX activity and bleed cessation in hemophilia B. Blood Adv. 2019;3(21): 3241-3247. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000 811. Erratum in: Blood Adv. 2020;4(15):3668. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002987.

25. Bolous NS, Chen Y, Wang H, et al. The cost-effectiveness of gene therapy for severe hemophilia B: a microsimulation study from the United States perspective. Blood. 2021;138(18) :1677–1690. doi 10.1182/blood.2021010864.

26. Meier N, Fuchs H, Galactionova K, Hermans C, Pletscher M, Schwenkglenks M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of etranacogene dezaparvovec versus extended half-life prophylaxis for moderate-to-severe haemophilia B in Germany key points for decision makers. Pharmacoecon Open. 2024;8(3): 373–387. doi:10.1007/s41669-024-00480-z.

27. Capucho HC, Salomon FCR, Vidal AT, Louly PG, Santos VCC, Petramale CA. Incorporation of techonologies in health in Brazil: a new model for the Brazilian public health system (Sistema Único de Saúde – SUS). BIS, Bol Inst Saúde. 2020; 13 (3):215-222

28. Ferreira AA, Brum IV, Souza JL, Leite ICG. Cost analysis of hemophilia treatment in a Brazilian public blood center (Custo-análise do tratamento da hemofilia em um hemocentro público brasileiro). Cad. Saúde Colet. 2020;28(4):556-566 2020. doi: 10.1590/1414-462X202028040484.

29. BPS Sistema de compras federais. BPS – Banco de Preços em Saúde 2023. Available at: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/banco-de-precos

30. Datasus. SIGTAP – sistema de gerenciamento da tabela de procedimentos, medicamentos e OPM do SUS 2023. Available at: http://sigtap.datasus.gov.br/tabela-unificada/app/sec/inicio.jsp

31. Earley J, Piletska E, Ronzitti G, Piletsky S. Evading and overcoming AAV neutralization in gene therapy. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;41:836–845. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2022.11.006

32. Ronzitti G, Gross DA, Mingozzi F. Human immune responses to adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors. Front Immunol. 2020;11:670. doi: 10.3389 /fimmu.2020.00670.

33. IBGE. Tabela 2645: Estimativas populacionais das medianas de altura e peso de crianças, adolescentes e adultos, por sexo, situação do domicílio e idade – Brasil e Grandes Regiões 2008. Rio de Janeiro:IBGE.

34. ISPOR. International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. Health care cost, quality and outcomes. 2009. Lawrenceville: ISPOR. 278p.

35. Pan American Health Organization. Health Technology Assessment. Available at https://www.paho.org/en/topics/health-technology-assessment , 22/12/2024

36. Mingozzi F, Maus MV, Hui DJ, et al. CD8(+) T-cell responses to adeno-associated virus capsid in humans. Nat Med. 2007;13(4):419-22. doi: 10.1038/nm1549.

37. Nathwani AC, Reiss UM, Tuddenham EG, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of factor IX gene therapy in hemophilia B. N Engl J Med. 2014;371 (21):1994-2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407309.

38. Chowdary P, Shapiro S, Makris M, et al. Phase 1-2 trial of AAVS3 gene therapy in patients with hemophilia B. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jul 21;387(3):23 7-247. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2119913. PMID: 35857660.

39. Konkle BA, Walsh CE, Escobar MA, et al. BAX 335 hemophilia B gene therapy clinical trial results: potential impact of CpG sequences on gene expression. Blood. 2021;137(6):763-774. doi: 10.1182/blood. 2019004625.

40. de Jong YP, Herzog RW. AAV and hepatitis: cause or coincidence? Mol Ther. 2022; 30(9):2875-2876. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.08.001

41. Anguela XM, High KA. Hemophilia B and gene therapy: a new chapter with etranacogene dezaparvovec. Blood adv. 2024;8(7):1796-1803. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010511.

42. Alshehri A, Dougherty JA, Beckman L, Svensson M. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of gene therapy for hemophilia type A and B. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2024 Oct;30(10):1178-1188. doi: 10.18553/ jmcp.2024.30.10.1178.

43. Björkman S. Prophylactic dosing of factor VIII and factor IX from a clinical pharmacokinetic perspective. Haemophilia. 2003; Suppl 1:101-8; discussion 109-10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.9.s1.4.x.

44. Yan S, McDade C, Thiruvillakkat K, Rouse R, Sivamurthy K, Wilson M. Analysis of long-term clinical and cost impact of etranacogene dezaparvovec for the treatment of hemophilia B population in the United States. J Med Econ. 2024; 27(1):758-765. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2024.2351762.

45. George LA, Sullivan SK, Giermasz A, et al. Hemophilia B gene therapy with a high-specific-activity factor IX variant. N Engl J Med. 2017;377 (23):2215-2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708538.

46. Cuker A, Kavakli K, Frenzel L, et al. Gene therapy with fidanacogene elaparvovec in adults with hemophilia B. N Engl J Med. 2024; 391 (12):1108-1118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2302982.

47. Keam SJ. Concizumab: first approval. Drugs. 2023;83(11):1053-1059. doi: 10.1007/s40265-023-01912-6. Erratum in: Drugs. 2023;83(13):1253-1254. doi: 10.1007/s40265-023-01924-2.

48. Mullard A. FDA approves first anti-TFPI antibody for haemophilia A and B. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2024; 23(12):884. doi: 10.1038/d41573-024-00175-4.

49. Mahlangu JN. Progress in the development of anti-tissue factor pathway inhibitors for haemophilia management. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:670526. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.670526.

50. Harmatz P, Prada CE, Burton BK, et al. First-in-human in vivo genome editing via AAV-zinc-finger nucleases for mucopolysaccharidosis I/II and hemophilia B. Mol Ther. 2022;30(12):3587-3600. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.10.010.

51. Shah J, Kim H, Sivamurthy K, Monahan PE, Fries M. Comprehensive analysis and prediction of long-term durability of factor IX activity following etranacogene dezaparvovec gene therapy in the treatment of hemophilia B. Curr Med Res Opin. 2023;39(2):227-237. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2022.2133492

52. Arvanitakis A, Jepsen C, Andersson NG, Baghaei F, Astermark J. Primary prophylaxis implementation and long-term joint outcomes in Swedish haemophilia A patients. Haemophilia. 2024;30(3):671-677. doi: 10.1111/hae.15013.

53. George LA, Ragni MV, Rasko JEJ, et al. Long-term follow-up of the first in human intravascular delivery of AAV for gene transfer: AAV2-hFIX16 for severe hemophilia B. Mol Ther. 2020;28(9):2073-2082. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.06.001.

54. Cohen JP. Despite eye-popping $3.5 million price tag for gene therapy hemgenix, budget impact for most payers will be relatively small. Forbes, Dec 2, 2022

55. Kansteiner F, Becker Z, Liu A, Sagonowsky E, Dunleavy K. Most expensive drugs in the US in 2023. Fierce Pharma, May 22, 2023

56. Hermans C, Marino R, Lambert C, et al. Real-world utilisation and bleed rates in patients with haemophilia B who switched to recombinant factor IX fusion protein (rIX-FP): a retrospective international analysis. Adv Ther. 2020;37(6):2988-2998. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01300-6.

57. Chen P, Han S. (2022). An Update on the Current Management of Hepatitis B Virus in Special Populations. Med Res Arch. 2022;10(11). doi:10. 18103/mra.v10i11.3315

58. Brasil. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Brasília, DF: Senado Federal; 1988. Available at: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm