PET/CT in Rare Autoimmune Diseases: A Comprehensive Review

Use of Pet/CT in different scenarios on rare and orphan diseases of autoimmune origin

Liset Sánchez Ordúz1, Marylin Acuña Hernandez2, Gerardo H. Cortés Germán3,

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 December 2024

CITATION: SÁNCHEZ ORDÚZ, Liset; ACUÑA HERNANDEZ, Marylin; CORTÉS GERMÁN, Gerardo H.. Use of Pet/CT in different scenarios on rare and orphan diseases of autoimmune origin. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 12, n. 12, dec. 2024. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/5994>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i12.5994

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Autoimmune diseases are on the rise, likely due to a combination of genetic predisposition, dietary changes, climate modifications, and exposure to xenobiotics. These diseases can affect five, people, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, which has a low prevalence of 5 per 10,000 people, are potentially fatal, chronically debilitating, and have a genetic origin.

In the United States, the National Conference of State Legislatures’ defined them as diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 Americans, considering them neglected diseases. Their treatments are not profitable due to their rarity.

This type of pathology presents a challenge in diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up challenges. The biological heterogeneity of autoimmune diseases leads to difficulties in clinical diagnosis, and the lack of specific diagnostic tests complicates the identification of these diseases.

In this review, we will discuss the role of Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (PET/CT), as it is a non-invasive imaging technique that allows for the execution of staging, prognosis, treatment planning, evaluation of therapeutic response, and follow-up of patients.

Keywords

Autoimmune diseases, PET/CT, rare diseases, orphan diseases, imaging techniques

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO)¹, orphan or rare diseases include around 5,500 diseases that can affect approximately 30 million people in the United States, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)².

European Commission³, considering rare diseases have a low prevalence of 5 per 10,000 people, are potentially fatal, chronically debilitating, and have a genetic origin.

In the United States, the National Conference of State Legislatures⁴ defines them as diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 Americans, considering them neglected diseases. Their treatments are not profitable due to their cost.

This type of pathology presents a diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up challenge. The natural history of these diseases needs to be better known and studied. Their biology is complex, leading to difficulties in developing drugs, biological products, and devices to treat these conditions.

For this reason, in 1997, INSERM (French National Institute of Health and Medical Research), with subsequent support from the European Commission starting in 2002, created the Orphanet strategy⁵. This strategy includes multiple medical aspects of this type of pathology, including a comprehensive classification for the methodology explained later.

As for autoimmune diseases, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)⁶ and the National Cancer Institute (NCI)⁷ define these pathologies as those in which antibodies are formed that attack the immune system.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a study program by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), found that approximately 32% of adults aged 60 or older may have at least four autoantibodies. Globally, an increase in the frequency of autoimmune diseases has been observed, with an estimated annual increase in incidence and prevalence of 19.1% and 12.5%, respectively⁸.

In recent years, there has been a rise in the use of Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (PET/CT), as it is a non-invasive imaging study used as a diagnostic method in various clinical scenarios: detection, classification, staging, prognosis, treatment planning, evaluation of response to therapy, and surveillance in oncological, cardiovascular, neurological, inflammatory, and infectious disorders, among others⁹.

We did not find a specific list of autoimmune and orphan diseases; therefore, we combined the lists to identify orphan autoimmune diseases.

For this reason, this scoping review aims to describe the different PET/CT tracers used in rare or orphan diseases of autoimmune origin, as defined in the ICD-11 classification.

Methodology

REVIEW QUESTION

What utility and characteristics are reported in the literature regarding using PET/CT with its different tracers in autoimmune orphan diseases?

The databases of available orphan diseases from Orphanet and autoimmune diseases from the Global Autoimmune Institute were cross-referenced, resulting in a list of orphan autoimmune diseases.

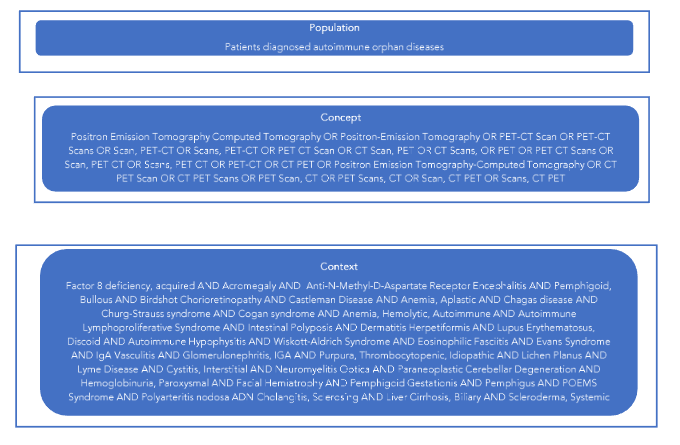

The study employed the broad population, concept, and context (PCC) framework indicated by the Joanna Briggs Institute for scoping reviews, as illustrated in Figure 1.

ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA

Articles were deemed eligible for inclusion if they reported case reports, case series, descriptive, or analytical observational studies published without date limitation that included the orphan autoimmune diseases from the cross-referenced list created for this study in which a PET/CT study had been conducted.

During the literature review, the following diseases were excluded due to the quantity and quality of available information, which allows for the execution of systematic reviews: polymyositis, immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, sarcoidosis, reactive arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, myopathies, myositis, myasthenia gravis, connective tissue diseases, Guillain-Barré syndrome, IgG4-related disease, giant cell arteritis, antiphospholipid syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, autoimmune hepatitis, autoimmune pancreatitis, dermatomyositis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and autoimmune diseases of the nervous system.

SEARCH STRATEGY

Initially, considering the methodology described by the Joanna Briggs Institute for scoping reviews, two researchers conducted a systematic search independently in indexed databases such as MEDLINE, OVID (including Embase), Cochrane Library, Epistemonikos, Scielo, LILACS, and JBI Evidence Synthesis, and gray literature such as OpenGrey and GreyNet using all the keywords included in the DECS, MESH, and Entry Terms. Annex 1 contains the search methodology.

SOURCE OF EVIDENCE SELECTION

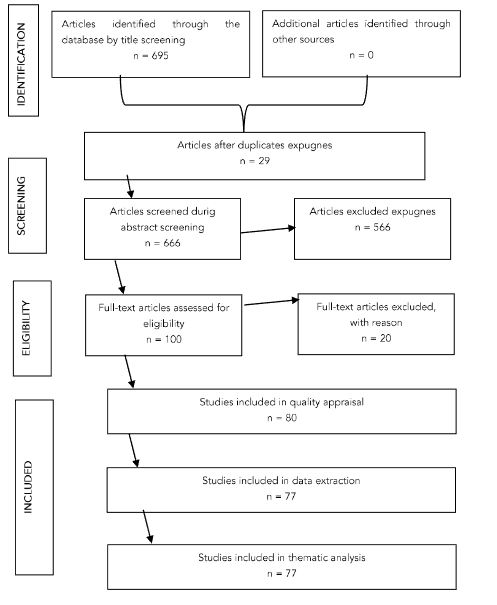

All search result articles were uploaded to Mendeley Software, and duplicates were removed. Subsequently, two independent reviewers assessed the titles and abstracts, selecting the compositions according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. When there were disagreements between the reviewers, an additional reviewer was consulted, and an agreement was reached. This section’s results are presented as a flow diagram (Figure 2) following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines.

DATA EXTRACTION

For data extraction, two reviewers considered specific details of the articles, such as authors, year of publication, type of study, disease, PET/CT tracer, and main findings.

The items to be assessed by the two reviewers were not disagreeable, and complete information was found in the included articles to evaluate the results.

Results

The results obtained from the literature review are summarized by disease in the tables described below.

Table 1 – Acromegaly

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bashari et al.¹⁰ | 2020 | Cross-sectional | L-[methyl¹¹C]-methionine or L-[carboxyl¹¹C]methionine | Focal tracer uptake in the lateral sellar and parasellar region |

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel et al.¹¹ | 2021 | Cross-sectional | [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-DOTA-TATE | A significant inverse relationship between postoperative values and the SUVmax at the sellar region |

| Daya et al.¹² | 2021 | Case report | [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-DOTA-TATE | Receptor activity in the pituitary gland due to physiological somatostatin receptor expression |

| Ahsan et al.¹³ | 2021 | Case report | [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC | Hyperplastic left adrenal gland with increased radiotracer uptake compared to the right |

| Alobaid et al.¹⁴ | 2023 | Case report | [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-DOTA-PEPTIDE | Intense focus on the uptake of the pituitary gland |

| Haberbosch et al.¹⁵ | 2023 | Case report | L-[methyl¹¹C]-methionine | Uptake on the left side of the sellar region |

| Chiloiro et al.¹⁶ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Excluded the presence of cancer |

| Bakker et al.¹⁷ | 2024 | Case series | [¹⁸F]FET | Suspicious parasellar tracer uptake |

Table 2. Aplastic Anemia, Aplastic Anemia and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, and Bullous Pemphigoid

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: Aplastic Anemia | ||||

| Matsuki et al.¹⁸ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake of [¹⁸F]FDG in pleura and lung |

| Disease: Aplastic Anemia AND Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | ||||

| Dudek et al.¹⁹ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Hypometabolic bone marrow activity |

| Disease: Bullous Pemphigoid | ||||

| Shrestha et al.²⁰ | 2022 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Left mediastinal lymphadenopathy and lung lesion |

| Grünig et al.²¹ | 2022 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Multiple small lesions of the skin distant from the known primary tumor locations |

Table 3. Chagas Disease

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: Chagas Disease | ||||

| Moll-Bernardes et al.²² | 2020 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG and [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC | Increased radiotracer uptake in the mid inferoseptal, mid anteroseptal, and basal inferolateral walls of the left ventricle |

| de Oliveira et al.²³ | 2023 | Cross-sectional | [¹⁸F]FDG and [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC | [¹⁸F]FDG and [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC uptake useful for detection of myocardial inflammation. [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC uptake may be associated with the presence of malignant arrhythmia |

Table 4. Castleman’s Disease

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: Castleman’s Disease | ||||

| Reddy et al.²⁴ | 2018 | Case series | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in cervical, mediastinal, and pelvic lymph nodes. Sclerotic bone lesions |

| Liu et al.²⁵ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in mesenteric lymph node and multiple lung nodules with slight FDG uptake |

| Zhang et al.²⁶ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in abdominal cavity |

| Maqbool et al.²⁷ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in right-sided neck mass and other lymph nodes of the head and neck |

| Yamauchi et al.²⁸ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | [¹⁸F]FDG uptake in idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease was significantly lower than in Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Zuo et al.²⁹ | 2024 | Case report | [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-DOTATATE, [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-Pentixafor | Positive uptake in the retroperitoneal mass |

| Aher P et al.³⁰ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Mixed-density mass with uptake in the right cardiogenic region |

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mashal et al.³¹ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the supraclavicular, mediastinal, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes, along with diffuse uptake in the spleen and soft-tissue nodules in the inferior and medial gluteal regions |

| Hu et al.³² | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in lymph nodes, spleen, bones, bone marrow, and nasopharynx, associated with multicentric Castleman disease |

Table 5. Castleman’s Disease AND POEMS Syndrome and Cogan’s Syndrome

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: Castleman’s Disease AND POEMS Syndrome | ||||

| Choe et al.³³ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Multiple lymph nodes, L1 sclerotic lesion, edema, and hepatosplenomegaly |

| Disease: Cogan’s Syndrome | ||||

| Balink et al.³⁴ | 2007 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the wall of the aortic arch; the aorta descends into the lateral wall |

| Örsal et al.³⁵ | 2014 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the walls of the arteries and knees |

| Cabezas-Rodríguez et al.³⁶ | 2019 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Increased metabolic activity of thoracic aorta and subclavian arteries |

| Matsui et al.³⁷ | 2021 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the aorta, bilateral carotid, iliac arteries, and celiac artery |

| Hafner et al.³⁸ | 2021 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Multiple liver abscesses and abdominal aortitis |

| Na et al.³⁹ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the subclavian and common carotid arteries, aortic arch, thoracic aorta, and coronary |

| Lu et al.⁴⁰ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the walls of the right head and arm, the left common carotid artery, and the starting segment of the left subclavian artery |

Table 6. Cold Agglutinin Disease and Churg-Strauss Syndrome

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: Cold Agglutinin Disease | ||||

| Nakamoto et al.⁴¹ | 2019 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Splenomegaly with diffuse uptake in bone marrow |

| Hayashi et al.⁴² | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in vertebral body, iliac bone, and spleen |

| Disease: Churg-Strauss Syndrome | ||||

| Horiguchi et al.⁴³ | 2014 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in lymphadenopathy in the mediastinal and hilar region |

Table 7. Eosinophilic Fasciitis

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: Eosinophilic Fasciitis | ||||

| Narváez et al.⁴⁴ | 2019 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Diffuse and symmetrical uptake in the fascia of the legs and thighs |

| Barlet et al.⁴⁵ | 2020 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptakes in the shoulders, wrists, knees, and ankles |

| Song et al.⁴⁶ | 2021 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptakes in subcutaneous fat and muscle |

| Chalopin et al.⁴⁷ | 2021 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in bone lesions |

| Barlet et al.⁴⁵ | 2021 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Diffuse uptake of the muscular fasciae |

| Laria et al.⁴⁸ | 2022 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Diffuse uptake in the muscles of the forearms and both lower limbs |

| Amrane et al.⁴⁹ | 2022 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in subcutaneous nodules, muscle fascia, and diffuse uptake on the synovial walls of both knees |

| Benzaquen et al.⁵⁰ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Generalized hypermetabolism of the fasciae and foci adjacent to the muscles and subcutaneous tissue |

| Fevrier et al.⁵¹ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake of fascia in the lower and upper limbs |

Table 8. Henoch-Schönlein Purpura and Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: Henoch-Schönlein Purpura | ||||

| Sabzevari et al.⁵² | 2018 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in subclavian, brachiocephalic, abdominal aortic, iliac, and femoral arteries |

| Gultekin et al.⁵³ | 2021 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in cavitary nodular lesions and hilar lymphadenomegaly |

| Disease: Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura | ||||

| Razanamahery et al.⁵⁴ | 2021 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in peri-nephric fat fibrosis, mediastinal lymph nodes, and a low tracer uptake on the testis |

| Ren et al.⁵⁵ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in lymph nodes in numerous regions of the body |

Table 9. Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder | ||||

| Alkhaja et al.⁵⁶ | 2021 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake along the entire spinal cord, suggestive of extensive acute myelitis |

| Ding et al.⁵⁷ | 2021 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the cervicothoracic, thoracic, and rectal wall |

| Fujisawa et al.⁵⁸ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]Flutemetamol, [¹⁸F]MK6240 (TAU), [¹⁸F]FDG | [¹⁸F]Flutemetamol uptake in the frontal and parietal lobes, posterior cingulate gyrus, and precuneus. [¹⁸F]MK6240 (TAU) uptake in the medial temporal, parietal, and frontal lobes; posterior cingulate gyrus; and precuneus. [¹⁸F]FDG showing decreased glucose metabolism from the inferior parietal lobule to the mid posterior temporal lobe, frontal association cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and precuneus, predominantly on the left side |

| Vîlciu et al.⁵⁹ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in pulmonary neoplasm with lymph node and adrenal metastases |

Table 10. Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus | ||||

| Dhull et al.⁶⁰ | 2016 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the left paravertebral region at the level of the left renal hilum, oral cavity, and left lung upper lobe |

| Lim et al.⁶¹ | 2017 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in multiple enlarged lymph nodes |

| Khurana et al.⁶² | 2020 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake mass lesion in the middle mediastinum in the subcarinal location extending into the transverse pericardial sinus |

| Chen et al.⁶³ | 2020 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake soft tissue mass in the right anterior-inferior mediastinum, right parasternal adenopathy, and pleural effusion |

| Liska et al.⁶⁴ | 2022 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in left tonsil area |

| Daniels et al.⁶⁵ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the mediastinum |

| Lu et al.⁶⁶ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in neck lymphadenopathies |

Table 11. Paraneoplastic Pemphigus AND Castleman’s Disease and Paraneoplastic Cerebellar Degeneration

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus AND Castleman’s Disease | ||||

| Fu et al.⁶⁷ | 2018 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the oral lesions and a heterogeneous soft tissue mass in the lower right retroperitoneum |

| Liu et al.⁶⁸ | 2011 | Case series | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the head of the pancreas |

| Fu et al.⁶⁹ | 2018 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake mass in the lower right retroperitoneum |

| Wang et al.⁷⁰ | 2019 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the head of the pancreas |

| Relvas et al.⁷¹ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in retroperitoneal lymphadenopathies and lobulated mass |

| Disease: Paraneoplastic Cerebellar Degeneration | ||||

| Rodriguez Herrera et al.⁷² | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in orbitofrontal hypermetabolism, mesial temporal, and bilateral regions |

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takahashi et al.⁷³ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG / [¹²³I]IMP SPECT | [¹⁸F]FDG uptake in lung tumor and mediastinal lymph nodes; [¹²³I]IMP SPECT shows normal blood flow in the cerebellum |

| Kalantari et al.⁷⁴ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the annex |

| Imai et al.⁷⁵ | 2022 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in the left neck |

Table 12. POEMS Syndrome

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: POEMS Syndrome | ||||

| Pan et al.⁷⁶ | 2015 | Cross-sectional | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in solitary and multiple hypermetabolic bone lesions, lymph nodes, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, central nervous system, serous cavity effusion, and gynecomastia |

| Allam et al.⁷⁷ | 2022 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in axillary and retropectoral lymph nodes and systemic fibrosis process involving pleural spaces, mediastinum, and pelvis |

| Genicon et al.⁷⁸ | 2022 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in osteolytic lesion in the right femur |

| Gültekin et al.⁷⁹ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake diffuses in muscle |

| Aderhold et al.⁸⁰ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in osteosclerotic pelvic, vertebral, and clavicular bone lesions and hilar lymphadenopathy |

Table 13. Polyarteritis Nodosa and Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease: Polyarteritis Nodosa | ||||

| Kang et al.⁸¹ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in lower extremities |

| Taimen et al.⁸² | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in peri- and intramuscular arterial areas of the lower extremities and liver |

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of Study | PET/CT Tracer | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Makiyama et al.⁸³ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in nodule in the right lower lung, right pulmonary artery embolism, and precordial subcutaneous tissue nodule |

| Philip et al.⁸⁴ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in soft tissues and intramuscular arterial tree |

| Taniguchi et al.⁸⁵ | 2024 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in medium-sized vessels |

| Disease: Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome | ||||

| Khan et al.⁸⁶ | 2022 | Case report | [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-DOTA-TATE | Uptake associated with the contrast agent in both adrenal glands and calcified thyroid nodules |

| Disease: Scleroderma | ||||

| Diaz Menindez et al.⁸⁷ | 2023 | Case report | [¹⁸F]FDG | Uptake in multifocal osseous regions, particularly in the spine and pelvis |

Discussion

Autoimmune diseases are characterized by spontaneous hyperactivity of the immune system, leading to the production of additional antibodies, which often results in inflammation that can affect all organs and tissues of the body, especially lymphoid tissues, joints, skin, muscles, salivary glands, blood vessels, and bone marrow.⁸⁸

As established in the results section, multiple autoimmune diseases are considered within the spectrum of orphan diseases. Therefore, from the perspective of molecular diagnostic studies, this review aimed to compile the available findings in the literature so that readers can become familiar with these types of pathologies and find a diagnostic aid for these conditions in these studies.

As for the pathophysiology, inflammation is the host’s initial defense against pathogens and other triggering stimuli. It plays an essential role in tissue repair and eliminating harmful pathogens. However, an inadequate response can damage normal cells adjacent to the affected tissue. In many autoimmune diseases, sterile inflammation occurs.

Molecular imaging allows for the visualization, characterization, and measurement of biological processes at the molecular and cellular levels, with PET/CT being the most widely used molecular imaging study in clinical practice.⁸⁹

The European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM), in conjunction with the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI), published a guideline in 2013 on the use of [¹⁸F]FDG in inflammation and infection based on the evidence available at that time. In 2018, along with the PET Interest Group (PIG) and endorsed by the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, they published a guideline on the use of PET/CT in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with suspected or diagnosed large vessel vasculitis and Polymyalgia Rheumatica.

Over the last 10 years, the use of this diagnostic tool has rapidly evolved, and it is now considered the most utilized imaging study in nuclear medicine for diagnosing and treating various inflammatory disorders.⁹⁰

[¹⁸F]FDG is the most commonly used PET tracer; as a glucose analog, it is taken up by cells with high metabolic activity.

[¹⁸F]FDG, once phosphorylated within the cell, is not further metabolized, resulting in its continuous accumulation inside cells. This property allows PET equipment to detect the emitted photons for imaging purposes (Molecular Imaging of Autoimmune Diseases and Inflammation).

Inflammatory processes exhibit increased FDG uptake because infiltrating inflammatory cells express high levels of glucose transporters, especially GLUT1 and GLUT3. These cells also demonstrate greater glucose consumption than non-inflammatory peripheral cells, leading to increased glucose metabolism due to oxidative bursts in inflammatory cells.⁹¹

This is evidenced in our review, where the predominant finding across all the pathologies discussed was an increased uptake of FDG in affected organs or tissues. Some reports show SUVmax values greater than 4 in Castleman’s disease (CD), generalized Wegener’s granulomatosis, POEMS syndrome, and eosinophilic fasciitis. Additionally, PET/CT helped guide the diagnosis by identifying primary tumors in some cases of metastatic lesions in patients with paraneoplastic pemphigus.

Cogan’s syndrome is a rare disease of unknown origin characterized by ocular inflammation and audiovestibular symptoms; only about 5% of patients present with systemic manifestations such as vasculitis or aortitis. In this context, PET/CT facilitated the diagnosis of systemic involvement by revealing increased metabolism in the walls of blood vessels such as the thoracic aorta and subclavian arteries, as reported by Cabezas-Rodríguez et al.³⁶ and Lu et al.⁴⁰, with vasculitis affecting the brachiocephalic trunk, common carotid artery, and left subclavian artery.

Yamauchi et al. reported a case of bilateral supraclavicular and mediastinal lymph nodes showing significant FDG uptake (SUVmax 11.5). An initial biopsy of the left supraclavicular lymph node showed no evidence of malignancy and was initially diagnosed as idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease, later confirmed as Hodgkin lymphoma. PET/CT was crucial in reassessing the appropriateness of the initial diagnosis. Yamauchi and colleagues highlighted that [¹⁸F]FDG PET/CT can differentiate between the two pathologies, showing significantly lower FDG uptake and SUVmax values in non-malignant conditions compared to Hodgkin lymphoma.²⁸

Patients with chronic autoimmune and inflammatory diseases have been reported to have a higher risk of malignancy, with 2.4- and 2-fold increased risks for esophageal and pancreatic cancers, respectively. For lymphoma, the risk is approximately two times higher in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 3–6 times higher in systemic lupus erythematosus, and 9–18 times higher in Sjögren syndrome. In dermatomyositis and polymyositis, an incidence of seven times greater cancer risk compared to the general population has been reported.⁸⁸

Oh JR et al. suggest that PET/CT is valuable in differentiating malignancy from inflammation in systemic autoimmune diseases, especially using the spleen/liver SUVmax ratio—1.5 ± 0.6 in autoimmunity vs. 0.8 ± 0.02 in malignancy patients.⁸³

In conditions such as acromegaly, Chagas disease, and Castleman disease, case reports have shown PET/CT studies using ⁶⁸Ga-DOTATATE and ⁶⁸Ga-DOTATOC, demonstrating increased uptake of these radiopharmaceuticals. Their implementation is based on the overexpression of somatostatin receptors by inflammatory and immune cells in various tissues and blood vessels.⁹²

Potential uses also include amino acid-based tracers such as L-[methyl-¹¹C]-methionine (used by Bashari et al.¹⁰ and Haber-Bosch et al.¹⁵) or [¹⁸F]FET (used by Bakker et al.¹⁷) in acromegaly cases with suspected residual lesions in the central nervous system, guided by persistent biochemical abnormalities.

In the case of [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-Pentixafor, Zuo et al.²⁹ report that a higher CXCR4 expression may be present in a heterogeneous lymphoproliferative disease such as Castleman’s disease.

For [¹⁸F]Flutemetamol and [¹⁸F]MK6240 (TAU), neuromyelitis optica associated with Alzheimer’s disease is described as characterized by a marked accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) and a high degree of tau deposition, respectively.⁵⁸

With the above in mind, the use of PET/CT with different tracers in the case of orphan autoimmune diseases has expanded in recent years, as it allows for imaging of the processes influencing the microenvironment of inflamed tissues. This plays a significant role in the persistence of inflammatory processes in autoimmune diseases and provides a comprehensive view of systemic involvement, which can lead to more precise guidance for the treatment and follow-up of these diseases.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References

1. Rare diseases. World Health Organization. Accessed November 03, 2024. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/frequently-asked-questions/rare-diseases

2. Rare Diseases at FDA. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Updated December 12, 2022. Accessed November 03, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/patients/rare-diseases-fda

3. Rare diseases. European Commission. Accessed November 03, 2024. https://health.ec.europa.eu/rare-diseases-and-european-reference-networks/rare-diseases_en

4. Rare and Orphan Diseases. National Conference of State Legislatures. Updated May 26, 2023. Accessed November 03, 2024. https://www.ncsl.org/health/rare-and-orphan-diseases

5. What is Orphanet?. Orphanet. Updated October 14, 2023. Accessed November 03, 2024. https://www.orpha.net/es

6. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Autoimmune Diseases. Updated October 06, 2022. Accessed November 03, 2024. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/autoimmune-diseases

7. Autoimmune disease. National Cancer Institut (NIH). Accessed November 03, 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/autoimmune-disease

8. Miller FW. The increasing prevalence of autoimmunity and autoimmune diseases: an urgent call to action for improved understanding, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Curr Opin Immunol. 2023;80:102266. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2022. 102266.

9. Acuña M, Cortés QP, Sánchez L. Use of PET/CT as a diagnostic tool in various clinical scenarios related to systemic lupus erythematosus. Rev. Colomb. Reumatol. 2022;29(4): 331-334. doi:10.10 16/j.rcreue.2021.03.007.

10. Bashari WA, van der Meulen M, MacFarlane J, et al. 11C-methionine PET aids localization of microprolactinomas in patients with intolerance or resistance to dopamine agonist therapy. Pituitary. 2022;25(4):573-586. doi:10.1007/s11102-022-01229-9

11. Daniel KB, de Oliveira Santos A, de Andrade RA, Trentin MBF, Garmes HM. Evaluation of 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake at the pituitary region and the biochemical response to somatostatin analogs in acromegaly. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44(10):2195 -2202. doi:10.1007/s40618-021-01523-6

12. Daya R, Seedat F, Purbhoo K, Bulbulia S, Bayat Z. Acromegaly with empty sella syndrome. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. Published online July 1, 2021. doi:10.1530/EDM-21-0049

13. Saand AR, Alqaisi S, Gunaratne TN, Hasan S. Abstract #1003264: A Rare Case of Reversible Panhypopituitarism Secondary to Cavernous Internal Carotid Artery Aneurysm Successfully Treated with Pipeline Embolization. Endocr Pract. 2021 Jun;27(6):S121–2. doi: 10.1016/j.eprac.2021.04.727

14. Alsagheir O, Alobaid LA, Alswailem M, Al-Hindi H, Alzahrani AS. SAT613 A Novel NF1 Mutation As The Underlying Cause Of Dysmorphic Features And Acromegaly In An Atypical Case Of Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J Endocr Soc. 2023;7(Suppl 1):bvad114.1346. Published 2023 Oct 5. doi:10.1210/jendso/bvad114.1346

15. Haberbosch L, Gillett D, MacFarlane J, et al. Dual Role for l-[Methyl-11C]-Methionine PET in Acromegaly: Confirming Remission and Detecting Recurrence. J Nucl Med. 2024;65(2):327-328. Published 2024 Feb 1. doi:10.2967/jnumed.123.266446

16. Chiloiro S, Capoluongo ED, Costanza F, et al. The Pathogenic RET Val804Met Variant in Acromegaly: A New Clinical Phenotype?. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(3):1895. Published 2024 Feb 5. doi:10.3390/ijms25031895

17. Bakker LEH, Verstegen MJT, Manole DC, et al. 18F-fluoro-ethyl-tyrosine PET co-registered with MRI in patients with persisting acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2024;101(2):142-152. doi:10.11 11/cen.15079

18. Matsuki S, Taniuchi N, Okada N, et al. A Case of Immune Aplastic Anemia during Combined Treatment with Atezolizumab and Chemotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Nippon Med Sch. 2024;91(3):339-346. doi:10.1272/jnms.JNMS .2024_91-302

19. Dudek A, Riaz S, Priftakis D, Bomanji J. Pattern of Bone Marrow Hypometabolism on 18 F-FDG PET CT in Systemic Lupus Erythematous-Associated Aplastic Anemia. Clin Nucl Med. 2024;49(3):e113-e114. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000005033

20. Shrestha P, George MK, Baidya S, Rai SK. Bullous pemphigoid associated with squamous cell lung carcinoma showing remarkable response to carboplatin-based chemotherapy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16(1):184. Published 2022 May 5. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03323-9

21. Grünig H, Skawran SM, Nägeli M, Kamarachev J, Huellner MW. Immunotherapy (Cemiplimab)-Induced Bullous Pemphigoid: A Possible Pitfall in 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2022;47(2):185-186. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000003894

22. Moll-Bernardes RJ, de Oliveira RS, de Brito ASX, de Almeida SA, Rosado-de-Castro PH, de Sousa AS. Can PET/CT be useful in predicting ventricular arrhythmias in Chagas Disease?. J Nucl Cardiol. 2020;27(6):2417-2420. doi:10.1007/s1235 0-019-02014-1

23. de Oliveira RS, Moll-Bernardes R, de Brito AX, et al. Use of PET/CT to detect myocardial inflammation and the risk of malignant arrhythmia in chronic Chagas disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2023;3 0(6):2702-2711. doi:10.1007/s12350-023-03350-z

24. Reddy Akepati NK, Abubakar ZA, Bikkina P. Role of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography Scan in Castleman’s Disease. Indian J Nucl Med. 2018;33 (3):224-226. doi:10.4103/ijnm.IJNM_26_18

25. Liu M, Zhou J, Zhu W, Huo L, Cheng W. Mesenteric Castleman Disease Misdiagnosed as Lymph Node Metastasis of Rectal Cancer on 18 F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2023;48(11):985-986. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000004832

26. Zhang MY, Li J, Wang YN, Tian Z, Zhang L. Unicentric Castleman’s disease presenting as amyloid A cardiac amyloidosis: a case report. Ann Hematol. 2024;103(1):367-368. doi:10.1007/s0027 7-023-05493-y

27. Maqbool S, Javed A, Idrees T, Anwar S. Unicentric Castleman Disease: A Rare Diagnosis of Radiological and Histological Correlation. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;75(2):975-978. doi:10.1007/s12070-022-03253-4

28. Yamauchi H, Momoki M, Kamiyama Y, et al. Hodgkin Lymphoma-related Inflammatory Modification-displayed Castleman Disease-like Histological Features and Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography Usefulness for the Differential Diagnosis. Intern Med. 2024;63(7):993-998.

29. Zuo R, Xu L, Pang H. 68Ga-DOTATATE and 68Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT in a Patient with Castleman Disease of the Retroperitoneum. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14(4):372. Published 2024 Feb 8. doi:10.3390/diagnostics14040372

30. Aher P, Zughul R, Samtani S, Priya S, Siegel Y, Schettino C. Diaphragmatic Castleman’s disease: A rare lymphoproliferative disorder: Clinical and radiological perspectives. Radiol Case Rep. 2024;19(12):6390-6393. Published 2024 Sep 25. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2024.09.077

31. Mashal FA, Awad JA, Tillman BF, Mosse CA, Thandassery RB. Idiopathic Multicentric Castleman Disease With Thrombocytopenia, Anasarca, Fever, Reticulin Fibrosis/Renal Insufficiency, and Organomegaly (TAFRO) Syndrome in a Liver Transplant Recipient. ACG Case Rep J. 2024;11(8): e01446. Published 2024 Jul 27. doi:10.14309/crj. 0000000000001446

32. Hu S, Li Z, Zhang H, et al. Idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease and connective tissue disorder successfully treated by siltuximab: a pediatric case report. Transl Pediatr. 2024;13(5): 824-832. doi:10.21037/tp-23-605.

33. Choe YW, Chou E, Peker D. Multicentric Castleman Disease in the Setting of POEMS Syndrome. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024; 24(Suppl 1):S542. doi: 10.1016/S2152-2650(24)01655-0

34. Balink H, Bruyn GAW. The role of PET/CT in Cogan’s syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26 (12):2177-2179. doi:10.1007/s10067-007-0663-5

35. Orsal E, Uğur M, Seven B, Ayan AK, Içyer F, Yıldız A. The Importance of FDG-PET/CT in Cogan’s Syndrome. Mol Imaging Radionucl Ther. 2014;23(2):74-75. doi:10.4274/mirt.349

36. Cabezas-Rodríguez I, Brandy-García A, Rodríguez-Balsera C, Rozas-Reyes P, Fernández-Llana B, Arboleya-Rodríguez L. Late-onset Cogan’s syndrome associated with large-vessel vasculitis. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). 2019;15(5):e30-e32. doi:10.1016/j.reuma.2017.05.002.

37. Matsui Y, Makino T, Asano R, Hounoki H, Shimizu T. Immunohistochemical Examination of Cutaneous Vasculitis in a Case of Cogan’s Syndrome. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66(6):706. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_882_20

38. Hafner S, Seufferlein T, Kleger A, Müller M. Aseptic Liver Abscesses as an Exceptional Finding in Cogan’s Syndrome. Hepatology. 2021;73(5):20 67-2070. doi:10.1002/hep.31547.

39. Na G, Nan Z, Jingjing M, Lili P. A case report of Cogan’s syndrome with recurrent coronary stenosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1451113. Published 2024 Sep 12. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2024. 1451113

40. Lu C, Lv P, Zhu X, Han Y. Cogan’s Syndrome Combined with Hypertrophic Pachymeningitis: A Case Report. J Inflamm Res. 2024;17:1839-1843. Published 2024 Mar 20. doi:10.2147/JIR.S453071

41. Nakamoto R, Okuyama C, Utsumi T, Yamamoto Y. Splenic Marginal Zone B-Cell Lymphoma With Splenic Infarction in a Patient With Cold Agglutinin Disease. Clin Nucl Med. 2019;44 (5):e372-e374. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000002528

42. Hayashi K, Koyama D, Sato Y, Fukatsu M, Ikezoe T. Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma presenting cold agglutinin syndrome: Clonal expansion of KMT2D and IGHV4-34 mutations after COVID-19. Br J Haematol. 2023;203(5):e110-e113. doi:10. 1111/bjh.19106

43. Horiguchi Y, Tsurikisawa N, Harasawa A, et al. Detection of pulmonary involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss, EGPA) with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Allergol Int. 2014;63(1):121-123. doi:10.2332/allergolint.13-LE-0550

44. Narváez J, Juarez P, Morales Ivorra I, Rodriguez Bel L, Rodriguez Moreno J, Romera M. [18F] FDG PET/CT may be a useful adjunct in diagnosis of eosinophilic fasciitis. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). 2019;15(6):e142-e143. doi:10.1016/j. reuma.2017.09.004.

45. Barlet J, Virone A, Gomez L, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI findings of Shulman syndrome also known as eosinophilic fasciitis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48(6):2049-2050. doi:10.1007/ s00259-020-05172-4

46. Song Y, Zhang N, Yu Y. Diagnosis and treatment of eosinophilic fasciitis: Report of two cases. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(29):8831-8838. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8831

47. Chalopin T, Vallet N, Morel M, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis (Shulman syndrome), a rare entity and diagnostic challenge, as a manifestation of severe chronic graft-versus-host disease: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15(1):135. Published 2021 Mar 15. doi:10.1186/s13256-021-02735-3

48. Laria A, Lurati AM, Marrazza MG, Re K, Mazzocchi D, Faggioli P, et al. Ab1269 shulman’s disease or eosinophilic fasciitis, a rare fibrosing disorder: a case report treated with tocilizumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022 Jun;81(Suppl 1):1743.1-1743. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2022-eular.119

49. Amrane K, Le Meur C, Thuillier P, et al. Case report: Eosinophilic fasciitis induced by pembrolizumab with high FDG uptake on 18F-FDG-PET/CT. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1078560. Published 2022 Dec 20. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022. 1078560

50. Benzaquen M, Christ L, Sutter N, Özdemir BC. Nivolumab-induced eosinophilic fasciitis: An unusual immune-related adverse event that needs to be recognized by practitioners. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2023;150(4):304-307. doi:10.1016/j.ann der.2023.07.001

51. Fevrier A, Dufour PA. Eosinophilic Fasciitis Illustrated by 18 F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2024;49(4):e188-e190. doi:10.1097/RLU.00000000 00005094

52. Elliott L, Matthew Ho, Mediola I, 045 A rare cause of chest pain in a young female. J Rheumatol.2018;57(Suppl3):key075.269, doi:10.10 93/rheumatology/key075.269

53. Gultekin B, Torun E, Gul A, Kalayoglu-Besisik S. Cavitary primary pulmonary lymphoplasmocytic lymphoma complicating henoch–schönlein purpura. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2021;43(S3) :S33-S65. Doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2021.10.1035

54. Razanamahery J, Humbert S, Emile JF, et al. Immune Thrombocytopenia Revealing Enriched IgG-4 Peri-Renal Rosai-Dorfman Disease Successfully Treated with Rituximab: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:6 78456. Published 2021 Jun 16. doi:10.3389/fmed. 2021.678456.

55. Ren L, Liu W, Wu T, et al. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma and monoclonal gammopathy secondary to immune thrombocytopenic purpura: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2023;25(6):237. Published 2023 Apr 19. doi:10.3892/ol.2023.13823

56. Alkhaja MA, Cheng LTJ, Loi HY, Sinha AK. “Hot Cord” Sign on 18F-FDG PET/CT in a Patient With Acute Myelitis Due to Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. Clin Nucl Med. 2021;46(1):74-75. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000003367

57. Ding M, Lang Y, Cui L. AQP4-IgG positive paraneoplastic NMOSD: A case report and review. Brain Behav. 2021;11(10):e2282. doi:10.1002/brb 3.2282

58. Fujisawa C, Saji N, Takeda A, et al. Early-onset Alzheimer Disease Associated With Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2023;37(1):85-87. doi:10.1097/WAD.0000 000000000517

59. Vlaicu C, Caloianu I, Sirbu C. Late-onset AQP4 positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder – does it conceal a paraneoplastic syndrome?. IBRO Neurosci Rep. 2023;15:S292–3.doi:10.1016/j.ibne ur.2023.08.518

60. Dhull VS, Passah A, Rana N, Arora S, Mallick S, Kumar R. Paraneoplastic pemphigus as a first sign of metastatic retroperitoneal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: (18)F-FDG PET/CT findings. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2016;35(4):260-262. doi:10.1016/j.remn.2015.09.005

61. Lim JM, Kim JH, Hashimoto T, Kim SC. Lichenoid paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with follicular lymphoma without detectable autoantibodies. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43(5):613 -615. doi:10.1111/ced.13563.

62. Khurana R, Sharma S, Kumar S, Deshpande AA, Wadhwa D, Agasty S. Paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with a pericardial ectopic thymoma. J Card Surg. 2020;35(11):3141-3144. doi:10.1111/ jocs.14955

63. Chen X, Fu Z, Yang X, Li Q. 18F-FDG PET/CT in Follicular Dendritic Cell Sarcoma With Paraneoplastic Pemphigus as the First Manifestation. Clin Nucl Med. 2020;45(7):572-574. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000003065.

64. Liska J, Liskova V, Trcka O, et al. Oral presentation of paraneoplastic pemphigus as the first sign of tonsillar HPV associated squamous cell carcinoma. A case report. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2022;166 (4):447-450. doi:10.5507/bp.2021.039.

65. Daniels P, Liou YL, Scarberry KB, Sharma TR, Korman NJ. Paraneoplastic pemphigus in a patient with a locally invasive, unresectable type B2 thymoma complicated by an intestinal perforation. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;35:103-107. Published 2023 Mar 24. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.03.006

66. Lu SC, Chu HL, Yueh HZ, Lin CH, Chou Y. Paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with nonhuman papillomavirus-related tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(36):e39368. doi:10.1097/ MD.0000000000039368

67. Fu Z, Liu M, Chen X, Yang X, Li Q. Paraneoplastic Pemphigus Associated With Castleman Disease Detected by 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2018;43(6):464-465. doi:10.1097/ RLU.0000000000002072

68. Liu QY, Chen MC, Chen XH, Gao M, Hu HJ, Li HG. Imaging characteristics of abdominal tumor in association with paraneoplastic pemphigus. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21(1):83-88. doi:10.1684/ejd.2010.1187

69. Fu Z, Liu M, Chen X, Yang X, Li Q. Paraneoplastic Pemphigus Associated With Castleman Disease Detected by 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2018;43(6):464-465. doi:10.1097/ RLU.0000000000002072

70. Wang J, Wang X, Xu J, Song P. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma aggravated by hyaline-vascular Castleman’s disease in association with paraneoplastic pemphigus: study of the tumor and successful treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94(5) :578-581. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.09.009

71. Relvas M, Xará J, Lucas M, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman’s disease. J Paediatr Child Health. 2023;59(3):573-576. doi:10. 1111/jpc.16361

72. Rodriguez A, Tellez H, Martinez J, Pino Y. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration secondary to HER2-positive breast cancer.J Neurol Sci. 2023; 455. (Suppl 121186). doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2023.121186

73. Takahashi N, Igari R, Iseki C, et al. Paraneoplastic Cerebellar Degeneration Accompanied by Seropositivity for Anti-GAD65, Anti-SOX-1 and Anti-VGCC Antibodies Due to Small-cell Lung Cancer. Intern Med. 2024;63(6): 857-860. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.0738-22

74. Kalantari F, Schweighofer-Zwink G, Hecht S, Rendl G, Pirich C, Beheshti M. 18F-FDG PET/CT in assessment of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration as the first sign of occult fallopian tube serous cystadenocarcinoma: Case report. 18F-FDG PET/CT zur Beurteilung einer paraneoplastischen Kleinhirndegeneration als erstes Zeichen eines okkulten serösen Zystadenokarzinoms des Eileiters: Fallbericht. Rofo. 2024;196(8):850-851. doi:10.1055/a-2272-5346

75. Imai T, Shinohara K, Uchino K, et al. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration with anti-Yo antibodies and an associated submandibular gland tumor: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2022; 22(1):165. Published 2022 May 2. doi:10.1186/s12 883-022-02684-4

76. Pan Q, Li J, Li F, Zhou D, Zhu Z. Characterizing POEMS Syndrome with 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2015;56(9):1334-1337. doi:10.2967/jnumed. 115.160507

77. Allam JS, Kennedy CC, Aksamit TR, Dispenzieri A. Pulmonary manifestations in patients with POEMS syndrome: a retrospective review of 137 patients. Chest. 2008;133(4):969-974. doi:10. 1378/chest.07-1800

78. Genicon C, Guilloton L, Pavic M, Le Moigne F. Skeletal lesions in POEMS syndrome. Joint Bone Spine. 2022;89(4):105324. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.20 21.105324

79. Gültekin B, kaya B, Göksoy Y, Altinkaynak M, Öneç B, et al. GTCL-223 Clonal CD4+ Cytotoxic T Lymphocytosis Concomitant With POEMS Syndrome: A Co-Existence of Key Findings for Relevance in the Pathogenesis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2023;23(Suppl 1):S467-468. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2152-2650(23)01390-3

80. Aderhold W, Lenz B, Hübner MP, et al. Intramedullary leukocytoclastic vasculitis and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation in POEMS syndrome. Ann Hematol. 2024;103 (4):1415-1417. doi:10.1007/s00277-024-05651-w

81. Kang JH, Kim J. Polyarteritis nodosa presenting as leg pain with resolution of positron emission tomography-images: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(4):918-921. doi:10.12 998/wjcc.v11.i4.918

82. Taimen K, Koskivirta I, Pirilä L, Mäkisalo H, Seppänen M, Allonen T. Polyarteritis nodosa with abdominal bleeding: imaging with PET/CT and angiography on the same day. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2024;8(3):rkae095. Published 2024 Aug 6. doi:10.1093/rap/rkae095

83. Makiyama A, Abe Y, Furusawa H, et al. Polyarteritis nodosa diagnosed in a young male after COVID-19 vaccine: A case report. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep. 2023;8(1):125-132. doi:10.10 93/mrcr/rxad037

84. Philip R, Nganoa C, De Boysson H, Aouba A. 18FDG PET/CT: an aid for the early diagnosis of paucisymptomatic polyarteritis nodosa. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2024;63(6):e181-e182. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kead655

85. Taniguchi Y, Yamamoto H. Muscular polyarteritis nodosa detected by FDG-PET/CT. Int J Rheum Dis. 2024;27(9):e15342. doi:10.1111/17 56-185X.15342

86. Khan G, Giacona J, Mirfakhraee S, Vernino S, Vongpatanasin W. MEN2B Masquerading as Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. JACC Case Rep. 2022;4(13):814-818. Published 2022 Jul 6. doi:10.1016/j.jaccas.2022.04.009

87. Diaz-Menindez M, Berianu F, Sullivan M. Incidental adenocarcinoma after bilateral lung transplant in a patient with scleroderma interstitial lung disease. J. Chest. 2023;164(4):a3405–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2023.07.2214

88. Oh JR, Song HC, Kang SR, et al. The Clinical Usefulness of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in Patients with Systemic Autoimmune Disease. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;45(3):177-184. doi:10.1007/s13139 -011-0094-8

89. Wu C, Li F, Niu G, Chen X. PET imaging of inflammation biomarkers. Theranostics. 2013;3(7):4 48-466. Published 2013 Jun 24. doi:10.7150/thno.6592

90. Slart RHJA; Writing group; Reviewer group; FDG-PET/CT(A) imaging in large vessel vasculitis and polymyalgia rheumatica: joint procedural recommendation of the EANM, SNMMI, and the PET Interest Group (PIG), and endorsed by the ASNC. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45(7): 1250-1269. doi:10.1007/s00259-018-3973-8

91. Jamar F, Buscombe J, Chiti A, et al. EANM/SNMMI guideline for 18F-FDG use in inflammation and infection. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(4) :647-658. doi:10.2967/jnumed.112.112524

92. Anzola LK, Glaudemans AWJM, Dierckx RAJO, Martinez FA, Moreno S, Signore A. Somatostatin receptor imaging by SPECT and PET in patients with chronic inflammatory disorders: a systematic review. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46(12):2496-2513. doi:10.1007/s00259-019-04489-z.