Chronic Pain’s Impact on Sleep and Quality of Life in Seniors

Chronic pain can compromise sleep and quality of life in the older.

Glauber S. Brandão¹, Glaudson S. Brandão², Daiana G. Galvão¹, Adriana Bovi³, Luciana B. C. Rua³, João Pedro R. Afonso³, Miria C. Oliveira³, Rodrigo F. Oliveira³, Deise A. A. P. Oliveira³, Irane Oliveira-Silva³, Carlos H. M. Silva³, Pre Suzy Ngomo⁴⁵, Luciana P. M. Andraus³, Orlando A. Guedes³, Rodolfo P. Vieira³, Claudia S. Oliveira³, Rodrigo A. C. Andraus³, Luis V. F. Oliveira³

- University of the State of Bahia – UNEB, Department of Education (DEDC-VII), Senhor do Bonfim (BA), Brazil.

- MAIS – Diagnostic and Specialty Clinic, Senhor do Bonfim (BA), Brazil.

- Master Degree and PhD Post Graduate Program in Human Movement and Rehabilitation, Evangelical University of Goiás – UNIEVANGELICA, Anápolis (GO), Brazil.

- Laboratoire de recherche biomécanique&neurophysiologie en réadaptation neuro-musculo-squelettique, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi (UQAC), Saguenay, Québec, Canada.

- Département des Sciences de la Santé, Physiothérapie de l’Université Gill offert en extension à l’Université du Québec à Chicoutimi (UQAC), Saguenay, Québec, Canada.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 September 2025

CITATION: Brandao, G. S., Galvao, D. G., Bovi, A., et al. Chronic pain can compromise sleep and quality of life in the older. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(9).

https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6976

COPYRIGHT:© 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI:https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6976

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Background: Age-related changes often disrupt sleep patterns, impacting overall health and quality of life, potentially leading to various health issues and societal challenges due to associated comorbidities and sleep deficiencies.

Aim: Test the association of chronic pain with the quality of sleep and health-related quality of life of older.

Methods: Clinical, anthropometric data, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; Visual analogue scale; cognitive impairment; World Health Organization Quality of Life-OLD and functional mobility was verified. The means between the groups were compared using the Student’s t test for independent samples, Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ) to test the associations and one-way analysis of variance to compare the means between the three age groups.

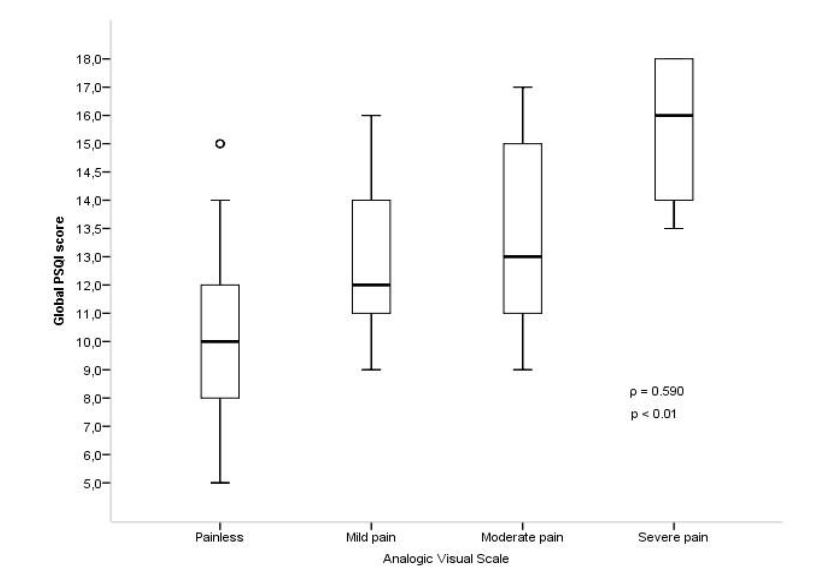

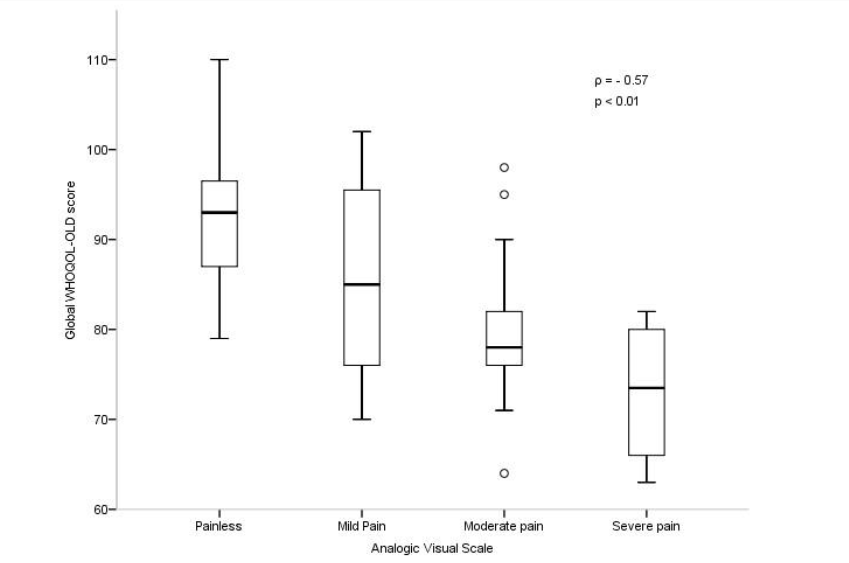

Results: Were involved 131 older, predominantly female (87%), average age 68 ± 7 years. There was a moderate (ρ = 0.590) and significant (p <0.01) positive correlation between Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores and chronic pain intensity and a negative moderate (ρ = – 0.57) and significant (p <0.01) correlation between quality of life and chronic pain.

Conclusion: Older people with chronic pain have worse quality of sleep and worse quality of life when compared to older without chronic pain.

Keywords:

Older, Sleep, Chronic Pain, Quality of Life, Functional Mobility

Introduction

Pain is a physical and emotional sign of bodily harm that largely interferes with a subject’s behavior, while sleep, which is influenced by behavior, is something necessary to maintain homeostasis and optimize the functions of different physiological systems. Humans need sleep to survive, so chronic deficiencies in the systems that regulate sleep can negatively impact health and quality of life. The aging process generates quantitative and qualitative interferences in sleep, causing a reduction in the ability to sleep well that may be associated with comorbidities and not only with age. These changes can cause several diseases and cause social and economic problems.

Chronic pain and poor sleep quality are biopsychosocial changes that are often associated with human aging and have a two-way correlation, that is, pain impairs sleep quality and sleep deprivation increases pain. These changes correspond to public health problems that have a significant functional and social impact on aging, increasing the morbidity and mortality of the older and negatively influencing their quality of life. Pain heightens cortical vigilance and can modify sleep patterns, alongside inducing discomfort, disheartenment, reliance on functionality, and disrupting everyday activities. The link between inadequate sleep and persistent pain could pertain to alterations in the central nervous system’s function, particularly within the thalamus. This area is intricately connected to both the perception of pain and the regulation of the sleep-wake cycle.

Chronic pain prevails significantly among individuals aged 60 and above, with rates ranging from 51% to 67%. It continues to be a primary concern for older individuals, often reported across medical facilities and outpatient settings. Yet, numerous elderly individuals and their families perceive pain as an inherent aspect of aging. Consequently, they tend to overlook discussing this issue, aiming to reduce the necessity for procedures, medications, and potential treatment side effects. Therefore, investigating the correlation between chronic pain and the quality of sleep as well as the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among older individuals can provide valuable insights for healthcare services. This information can aid in planning care strategies focused on prevention, early diagnosis, and appropriate treatment. The current study aimed to validate the hypothesis suggesting an interconnection between chronic pain, sleep quality, and HRQoL among older adults within the community.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study is designed as a cross-sectional quantitative investigation to explore the correlation between chronic pain, quality of sleep, and HRQoL (Health-Related Quality of Life) among older individuals. It’s part of a registered clinical trial (RBR-3cqzfy on ensaiosclinicos.gov.br) focusing on evaluating the impact of a home exercise program on sleep quality and HRQoL among older community members. The study’s structure and execution followed the guidelines outlined by the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE).

Data collection occurred between July and December 2021, following approval by the Ethics Committee at Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública – EBMSP (protocol number 39072514.6.0000.5544). As inclusion criteria, individuals from the local community, of both genders, over the age of 60, and who exhibited poor sleep quality according to the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), were involved in this study. Elderly individuals who exhibited any cognitive impairment identified through the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) were excluded.

Individual interviews were conducted to gather sociodemographic and anthropometric data, self-reported health conditions, presence of multimorbidity (≥ 2 chronic diseases), and a history of chronic pain. Functional mobility was assessed, and evaluation instruments employed included MMSE, Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), WHOQoL-OLD, and the Timed Up and Go test (TUG).

Instruments

The assessment instruments used in this study were employed in a prior study conducted by our group. These instruments encompass anthropometric measurements, sleep quality assessment, chronic pain evaluation, quality of life assessment, cognitive impairment assessment, and functional mobility evaluation.

Statistical analysis

The data underwent various normality testing methods, including histogram analysis, mean and median evaluation, standard deviation calculation, skewness and kurtosis assessment, and confirmation through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test. Prior to correlation analysis, checks for a linear relationship between variables and homoscedasticity were performed. Descriptive analysis involved absolute and percentage frequencies for categorical variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion for numerical ones. Differences between participants with and without a history of chronic pain were assessed using Student’s t-test for numerical variables and Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables.

Given that the variables didn’t meet all parametric test criteria, Spearman’s correlation coefficient (ρ) was used to analyze chronic pain intensity levels’ association with global PSQI scores and WHOQOL-OLD global scores. These correlations were presented using Box Plots. The Spearman correlation coefficient was also used to analyze the correlation between the number of chronic diseases and sleep quality as well as quality of life.

To compare sleep quality, quality of life, and functional mobility among three age groups of older adults (60 to 69, 70 to 79, and ≥ 80) with chronic pain, One-Way ANOVA was employed.

To compare the means of each PSQI component and each facet of the WHOQOL-OLD among elderly individuals with and without chronic pain, Student’s t-test for independent samples was used, and the magnitude of the difference between the groups was verified through the effect size calculated by Cohen’s methodology (Cohen’s d), which represents how much two means experienced in terms of standard deviations. Bootstrapping procedures (1000 resamplings; 95% CI BCa) were performed to obtain greater reliability of the results, to correct deviations from normality of the sample distribution and differences between group sizes.

The significance level was set at α ≤ 0.05 for decision criteria. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences® (SPSS), version 21, on the Windows® platform.

Results

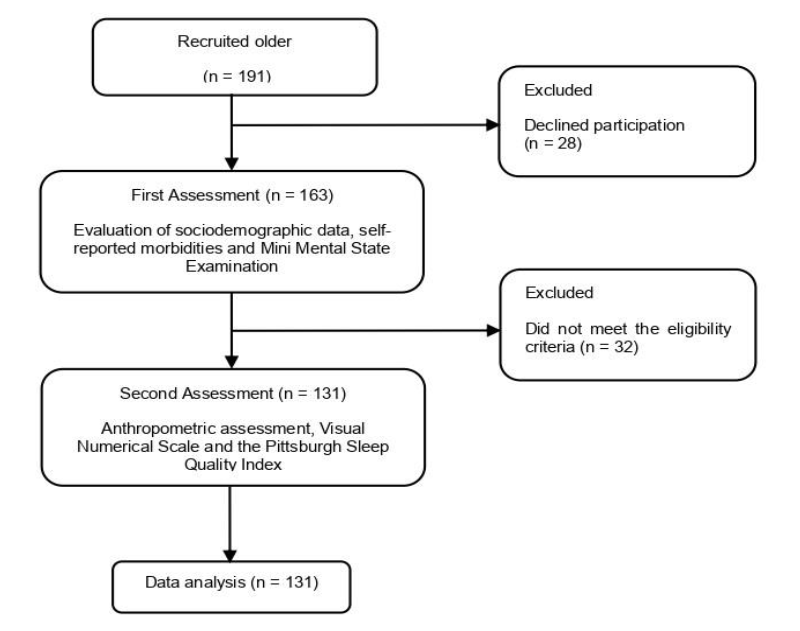

Initially, one hundred and ninety-one potential participants were recruited from the community. However, 28 refused to participate in the study and 32 did not meet the eligibility criteria, being evaluated 131 older people. It sounds like Figure 1 illustrates the participant flow throughout the study.

The sample is predominantly composed of women (87%), with an average age of 68 ± 7 years, with low education (86.3% with three or less years of study), low per capita income (84.8% ≤ 2 MW) and, mostly, living with family members (67.9%). Regarding the clinical characteristics, it turns out that 51 elderlies (39%) have chronic pain and, among these older with chronic pain, 12 (23.6%) reported mild pain, 31 (60.8%) reported moderate pain and 8 (15.6%) reported severe pain. Chronic diseases were identified in 70 elderly people (53.4%). The main ones observed were anxiety (58.8%), arthrosis (37.4%), systemic arterial hypertension (33.6%) and diabetes (26%). The prevalence of multimorbidity (≥ 2 morbidities) was 40.5%.

Table I displays a comparison of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between two groups: those with and without a history of chronic disease. The analysis indicates a statistically significant difference solely in terms of chronic disease and the TUG test. Older individuals with a history of chronic pain tend to have a higher incidence of chronic diseases and exhibit lower functional mobility compared to those without a history of chronic pain.

| Variables | History of chronic pain (n=54) | No history of chronic pain (n=80) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender female | 45 (88.3%) | 69 (86.3%) | ns |

| Age | 70 ± 7 | 69.9 ± 7 | ns |

| Education ≤ 3 years of study | 45 (88.4%) | 68 (85%) | ns |

| Per capita monthly income (≤ 2 MW) | 44 (86.4%) | 71 (88.8%) | ns |

| Household arrangement (lives with family members) | 35 (64.9%) | 54 (70.2%) | ns |

| BMI | 27.2 ± 4.5 | 27.3 ± 4.1 | ns |

| Chronic disease | 40 (78.5%) | 30 (37.5%) | < 0.01 |

| TUG in seconds | 9.0 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 1.9 | < 0.01 |

Figure 2 illustrates the correlation between the overall PSQI score, a measure of sleep quality, and the intensity of chronic pain measured via the visual analog scale. The data reveals a moderate (ρ = 0.590) and significant (p < 0.01) positive correlation between sleep quality and chronic pain intensity. This indicates that as the intensity of pain increases, there is a corresponding decline in sleep quality, as reflected by the increase in the PSQI score.

In the analysis of correlation between the number of self-reported chronic diseases and sleep quality, it was identified positive, moderate (ρ = 0.42) and statistically significant (p <0.01) correlation, whereas in the correlation of the number of chronic diseases with quality of life, it was identified a negative, strong (ρ = -0.78) and statistically significant (p <0.01) correlation. It demonstrates that the greater the number of chronic diseases, the worse the quality of sleep and the quality of life of the older.

The correlation between quality of life, using the WHOQOL-OLD global score, and pain intensity, using the visual analog scale, is shown in Figure 3, showing a moderate negative correlation (ρ = -0.57) and statistically significant difference (p <0.01) between quality of life and intensity of chronic pain. And the increase in pain intensity is associated with a reduction in the WHOQOL-OLD score.

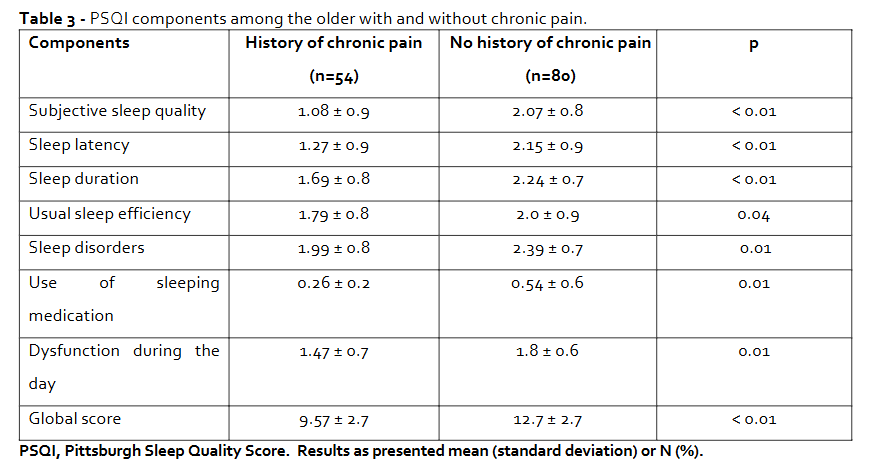

In table II, when dividing the older with a history of chronic pain into three age groups (60 to 69, 70 to 79 and ≥ 80) and making a comparative analysis of sleep quality, quality of life, number of morbidities and mobility between the three, it appears that the older with history of chronic pain, the worse their sleep quality, quality of life and functional mobility, but the number of morbidities does not change significantly with age. Table III presents a comparison between older individuals with and without a history of chronic pain concerning the components of the PSQI. The analysis demonstrates that older individuals experiencing chronic pain exhibit poorer sleep quality compared to those without chronic pain. This difference proves statistically significant across all components evaluated in the PSQI assessment.

| Variables | 60 to 69 years (n=26) | 70 to 79 years (n=18) | ≥ 80 years (n=10) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSQI | 11.19 ± 1.9 | 12.73 ± 1.5 | 13.83 ± 1.1 | < 0.01 |

| WHOQOL-OLD | 84.04 ± 9.8 | 80.9 ± 8.3 | 73.5 ± 5.1 | < 0.03 |

| Number of comorbidities | 18 (69.6%) | 13 (72.5%) | 7 (70%) | ns |

| TUG (seconds) | 8.53 ± 1.7 | 10.35 ± 2.1 | 12.01 ± 1.6 | < 0.01 |

Figure 4 illustrates the correlation between the components of the PSQI and the intensity of chronic pain. The analysis demonstrates that older individuals experiencing chronic pain exhibit poorer sleep quality compared to those without chronic pain.

Discussion

The study revealed that older individuals experiencing chronic pain exhibit inferior sleep quality and overall life quality in comparison to those without chronic pain. Moreover, it highlighted a positive, moderate, and significant correlation between pain intensity and PSQI scores. Additionally, it uncovered a negative, moderate, and significant correlation between pain intensity and quality of life. This indicates that higher pain intensity is associated with poorer sleep quality and decreased overall quality of life among older individuals.

In the sample of the present study there was a predominance of females (87%), reflecting the greater longevity of women, an aspect already highlighted in the literature. The feminization of old age can be attributed to various factors. Women tend to have a lower mortality rate from external causes, such as accidents or injuries. Additionally, they often exhibit lower prevalence in smoking and alcohol consumption compared to men. Furthermore, women are typically more proactive in self-care practices, contributing to their longevity and representation among the elderly population. However, epidemiological studies have shown that chronic pain disorders have a considerably higher prevalence in women than in men. The reasons why this gender difference appears are not yet fully elucidated. However, epidemiological studies suggest some hypotheses: women are the ones who most seek health services and are more willing than men to report pain; biological factors related to the action of estrogen and progesterone; cognitive and emotional characteristics such as stress, depression and catastrophization (believing that something is worse than it really is), have also been referred to as factors that contribute to different pain reactions between the two genders.

The sample involved had a mean age of 70 ± 8 years, converging with population-based studies, reinforcing the external validity of the present study. The majority of the older have a low level of education (69.4% with three or less years of study), reflecting the country’s socioeconomic inequality. Additionally, a low per capita income was identified (84.8% ≤ 2 minimum wages), as found in studies of epidemiological profile conducted in Brazilian cities and a strong and negative correlation between the number of chronic diseases and quality of life, demonstrating that the greater the number of chronic diseases, the worse the quality of life of the older, corroborating with previous studies.

Regarding the main outcome of this study, when analyzing the association of chronic pain with sleep quality, our results demonstrate that the increase in pain intensity is associated with worsening sleep quality and that the older with chronic pain had sleep quality worse when compared to the older without chronic pain. This corroborates with other studies, which collectively have accepted the idea that the relationship between pain and sleep is bidirectional, with pain interrupting sleep and sleep deprivation or disturbance increasing pain, one influencing the other and making it difficult to dissociation in clinical practice. However, some of the more recent studies have shown a direction of the association between sleep and pain, the results of which suggest that sleep disorders are more significant predictors of pain than in the opposite direction. Therefore, the so-called bidirectional association seems to be stronger in the sense that sleep interferes with pain than the opposite mechanism.

In the present study, we found that, among the older who have a history of chronic pain, sleep quality, quality of life and functional mobility worsened with advancing age, in line with previous studies. These studies have shown that pain or physical discomfort in the older leads to changes in sleep patterns that tend to progress with age, since with advancing age there may be an increase in the number of diseases and a gradual decline in the functions of organic systems, which can reduce physical capacity and emotional suffering with depressive symptoms, accelerating the aging process and interfering with the quality of sleep and quality of life of the older.

There was a positive correlation between the number of chronic diseases and scores of PSQI and a strong negative correlation between the number of chronic diseases and HRQoL, and the higher the number of self-reported chronic diseases, the worse the quality of sleep and the quality of life of the older. Sleep disorders can negatively impact chronic diseases, as there is an association of poor sleep with psychosocial symptoms such as depression and anxiety, in addition to causing an increased response to physiological stress and contributing to the systemic inflammatory process, enabling the development or worsening of diseases and the intensification of pain, declining quality of life.

In the present study, we identified that there is a moderate negative correlation between quality of life and pain intensity and that the older with chronic pain had a worse quality of life than the older without chronic pain. Cross-sectional studies reported a negative correlation between chronic pain and aspects of quality of life. Such relationships were found both in chronic pain cohorts and in population-based studies. In addition, systematic reviews confirmed evidence of a link between pain and poor quality of life. One of the systematic reviews reported a lack of evidence for a relationship between quality of life and pain intensity; however, this study found a negative relationship between quality of life and pain intensity. Thus, quality of life aspects were negatively associated with the presence and intensity of pain in the older population.

The results of the present study strengthen the hypothesis that sleep quality and pain have a two-way and reciprocal relationship, which allows us to discuss some clinical implementations. Health professionals who participate in the treatment of patients with chronic pain and/or chronic illness, in addition to using interventions that alleviate symptoms, should also pay attention to the assessment and treatment of sleep disorders, since only secondary attention is often given to these disorders. Therefore, the findings of the present study are in line with previous study and recommendations by suggesting that sleep assessment should be routinely addressed in the management of patients with chronic pain and/or chronic disease in terms of assessment, monitoring and definition of therapeutic strategies. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach is often necessary to obtain more comprehensive results regarding the care of the older.

Study Limitations

Certainly, a primary limitation of this study pertains to its utilization of a cross-sectional design. This approach doesn’t facilitate the exploration of temporal associations between variables. Consequently, interpretations regarding the relationships observed between chronic pain, quality of sleep, and quality of life among older individuals should be approached with caution due to the inability to establish causal or temporal sequences of events. Absolutely, the bidirectional relationship among the studied variables indicates a reciprocal influence. However, the study’s design doesn’t permit causal inference. Reliance on self-reported measures represents another limitation, introducing the potential for measurement errors, recall biases, and the desire to present oneself favorably, possibly leading to an overestimation of issues. To overcome these limitations, future research endeavors should consider employing objective methods such as polysomnography. Additionally, longitudinal studies assessing variables at multiple time points over an extended duration are imperative. These methodologies would better capture and elucidate the causal relationships between the variables under investigation.

Conclusion

The results of this study corroborate with our hypothesis that the older with a history of chronic pain have worse quality of sleep and quality of life when compared to the older without a history of chronic pain and that there is a correlation between chronic pain and quality of sleep and quality of life, and the greater the intensity of pain, the worse the quality of sleep and life of the older. It was also identified that the greater the number of chronic diseases, the worse the quality of sleep and quality of life and that, the older the older with chronic pain, the worse their quality of sleep, functional mobility and quality of life.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Financial support:

This research received no external funding.

Funding Statement:

This study was funded by the Universidade do Estado da Bahia, through the Support Program for Training of Teachers and Administrative Technicians (PAC); RPV receive grants Research Productivity, modality PQII of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (local acronym CNPq), Brazil. CSO receive grants Research Productivity, modality PQII of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (local acronym CNPq), Brazil. LVFO receive grants Research Productivity, modality PQII; Process no. 310241/2022-7 of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (local acronym CNPq), Brazil. These grants do not influence any of the stages of the study, from the conception, development, analysis, and interpretation of the results.

References:

- Smith M, Haythornthwaite J. How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain inter-relate? insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8(2):119-132.

- Landolt H, Borbély A. Age-dependent changes in sleep EEG topography. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112(2):369-377.

- Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep and its disorders in aging populations. Sleep Med. 2009;10(Suppl 1):S7-S11.

- Latham J, Davis B. The socioeconomic impact of chronic pain. Disabil Rehabil. 1994;16(1):39-44.

- Stranges S, Tigbe W, Gomez-Olive FX, et al. Sleep problems: an emerging global epidemic? findings from the INDEPTH WHO-SAGE study among more than 40,000 older adults from 8 countries across Africa and Asia. Sleep. 2012;35(8):1173-1181.

- Leys LJ, Chu KL, Xu J, et al. Disturbances in slow-wave sleep are induced by models of bilateral inflammation, neuropathic, and postoperative pain, but not osteoarthritic pain in rats. Pain. 2013;154(7):1092-1102.

- Haack M, Sanchez E, Mullington JM. Elevated inflammatory markers in response to prolonged sleep restriction are associated with increased pain experience in healthy volunteers. Sleep. 2007;30(9):1145-1152.

- Lavigne GJ, Okura K, Abe S, et al. Gender specificity of the slow wave sleep lost in chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain. Sleep Med. 2011;12(2):179-185.

- Pereira LV, Vasconcelos PP, Souza LAF, Pereira GA, Nakatani AYK, Bachion MM. Prevalence and intensity of chronic pain and self-perceived health among elderly people: a population-based study. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2014;22(4):662-669.

- Dellaroza MS, Pimenta CA, Matsuo T. Prevalence and characterization of chronic pain among the elderly living in the community. Cad Saude Publica. 2017;23(5):1151-1160.

- Rapo PS, Haanpaa M, Liira H. Chronic pain among community-dwelling elderly: a population-based clinical study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34(2):159-164.

- Oliveira CP, Santos IMG, Rocca AR, Dobri GP, Nascimento GD. Epidemiological profile of elderly patients treated in the emergency room of a university hospital in Brazil. Rev Med (Sao Paulo). 2018;97(1):44-50.

- Tompkins DA, Hobelmann JG, Compton P. Providing chronic pain management in the “fifth vital sign” era: historical and treatment perspectives on a modern-day medical dilemma. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173(Suppl 1):S11-S21.

- Santos FC, Souza PM, Nogueira SA, Lorenzet IC, Barros BF, Dardin LP. Self-management of chronic pain in the elderly: pilot study. Rev Dor. 2011;12(3):209-214.

- Brucki SMD, Nitrini R, Caramelli P, Bertolucci PHF, Okamoto IH. Suggestions for utilization of the mini-mental state examination in Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2003;61(3B):777-781.

- Ferreira-Valente MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain. 2011;152(10):2399-2404.

- Bertolazi AN, Fagondes SC, Hoff LS, et al. Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. Sleep Med. 2011;12(1):70-75.

- Fleck MPA, Chachamovich E, Trentini CM. WHOQOL-OLD project: method and focus group results in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2003;37(6):793-799.

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The Timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142-148.

- Brandão GS, Camelier FWR, Sampaio AAC, et al. Association of sleep quality with excessive daytime somnolence and quality of life of elderlies of community. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2018;13:27.

- Austad SN, Bartke A. Sex differences in longevity and in responses to anti-aging interventions: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2016;62(1):40-46.

- Luy M, Gast K. Do women live longer or do men die earlier? reflections on the causes of sex differences in life expectancy. Gerontology. 2014;60(2):143-153.

- Gustorff B, Dorner T, Likar R, et al. Prevalence of self-reported neuropathic pain and impact on quality of life: a prospective representative survey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(1):132-136.

- Borges PLC, Bretas RP, Azevedo SF, Barbosa JMM. A profile of elderly members of community groups in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24(12):2798-2808.

- Hunt K, Adamson J, Hewitt C, Nazareth I. Do women consult more than men? a review of gender and consultation for back pain and headache. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16(2):108-117.

- Craft RM, Mogil JS, Aloisi AM. Sex differences in pain and analgesia: the role of gonadal hormones. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(5):397-411.

- Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL 3rd. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10(5):447-485.

- Louvison MCP, Lebrão ML, Duarte YAO, Laurenti R. Inequalities in health conditions and use of services among elderly people in the city of São Paulo: an analysis of gender and income. Saude Colet. 2008;5(22):189-194.

- Borges JES, Camelier AA, Oliveira LVF, Brandão GS. Quality of life of elderly hypertensive and diabetics of the community: an observational study. J Physiother Res. 2019;9(2):74-84.

- Pimenta FB, Pinho L, Silveira MF, Botelho AC. Factors associated with chronic diseases in elderly people assisted by the Family Health Strategy. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;20(8):2489-2498.

- Ferretti F, Santos DT, Giuriatti L, Gauer APM, Teo CRP. Sleep quality in the elderly with and without chronic pain. Br J Pain. 2018;1(2):141-146.

- O’Brien EM, Waxenberg LB, Atchison JW, et al. Intraindividual variability in daily sleep and pain ratings among chronic pain patients: bidirectional association and the role of negative mood. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(5):425-433.

- Smith MT, Haythornthwaite JA. How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain inter-relate? insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8(2):119-132.

- Andersen ML, Araujo P, Frange C, Tufik S. Sleep disturbance and pain: a tale of two common problems. Chest. 2018;154(5):1249-1259.

- Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013;14(12):1539-1552.

- Afolalu EF, Ramlee F, Tang NKY. Effects of sleep changes on pain-related health outcomes in the general population: a systematic review of longitudinal studies with exploratory meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;39:82-97.

- Choy EH. The role of sleep in pain and fibromyalgia. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(9):513-520.

- Frange C, Hachul H, Hirotsu C, Tufik S, Andersen ML. Temporal analysis of chronic musculoskeletal pain and sleep in postmenopausal women. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(2):223-234.

- Maglione JE, Ancoli-Israel S, Peters KW, et al. Subjective and objective sleep disturbance and longitudinal risk of depression in a cohort of older women. Sleep. 2014;37(7):1179-1187.

- Quinhones MS, Gomes MM. Sleep in normal and pathological ageing: clinical and physiopathological aspects. Rev Bras Neurol. 2011;47(2):31-42.

- Brandão GS, Oliveira SG, Nogueira LD, et al. Impact of functional home training on postural balance and functional mobility in the elderlies. J Exerc Physiol Online. 2019;22(3):46-57.

- Cardoso AF. Particularities of the elderly: a review of the physiology of aging. Rev Digital. 2009;13(132):1-7.

- Haack M, Sanchez E, Mullington JM. Elevated inflammatory markers in response to prolonged sleep restriction are associated with increased pain experience in healthy volunteers. Sleep. 2007;30(9):1145-1152.

- Gerhart JI, Burns JW, Post KM, et al. Relationships between sleep quality and pain-related factors for people with chronic low back pain: tests of reciprocal and time of day effects. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(3):365-375.

- Breivik H, Eisenberg E, O’Brien T; on behalf of OPENminds. The individual and societal burden of chronic pain in Europe: the case for strategic prioritisation and action to improve knowledge and availability of appropriate care. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1229.

- Choi YS, Kim DJ, Lee KY, et al. How does chronic back pain influence quality of life in Koreans: a cross-sectional study. Asian Spine J. 2014;8(3):346-352.

- Froud R, Patterson S, Eldridge S, et al. A systematic review and meta-synthesis of the impact of low back pain on people’s lives. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:50.

- Bjornsdottir S, Jonsson S, Valdimarsdottir U. Mental health indicators and quality of life among individuals with musculoskeletal chronic pain: a nationwide study in Iceland. Scand J Rheumatol. 2014;43(5):417-423.

- Leadley RM, Armstrong N, Reid KJ, Allen A, Misso KV, Kleijnen J. Healthy aging in relation to chronic pain and quality of life in Europe. Pain Pract. 2014;14(6):547-558.

- Nygaard Andersen L, Kohberg M, Juul-Kristensen B, Gram Herborg L, Søgaard K, Røessler K. Psychosocial aspects of everyday life with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Scand J Pain. 2014;5(3):131-148.

- Cheatle MD, Foster S, Pinkett A, Lesneski M, Qu D, Dhingra L. Assessing and managing sleep disturbance in patients with chronic pain. Anesthesiol Clin. 2016;34(2):379-393.

- Oliveira TR, Moser ADL, Paz LP, et al. Sarcopenia, chronic pain, and perceived health of older: a cross-sectional study. Fisioter Mov. 2023;36:e36106.

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105-121.

- Ravyts SG, Dzierzewski JM, Raldiris T, Perez E. Sleep and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain in mid- to late-life: the influence of negative and positive affect. J Sleep Res. 2019;28(5):e12807.

- Malek-Ahmadi M, Kora K, O’Connor K, Schofield S, Coon D, Nieri W. Longer self-reported sleep duration is associated with decreased performance on the montreal cognitive assessment in older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28(2):333-337.

- Paladini A, Fusco M, Coaccioli S, Skaper SD, Varrassi G. Chronic pain in the elderly: the case for new therapeutic strategies. Pain Physician. 2015;18(5):E863-E876.