Pentosan Polysulfate: A Novel Approach for SARS-CoV-2

Pentosan Polysulfate, An Anti-Viral Heparinoid, Prevents Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona Virus-2 Infection and Treats Symptoms of Long Coronavirus Disease

Margaret M. Smith1, James Melrose1,2,3*

- Raymond Purves Bone and Joint Research Laboratory, Kolling Institute, St. Leonards, NSW 2065, Australia.

- School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney at Royal North Shore Hospital, St. Leonards, NSW 2065, Australia.

- Graduate School of Biomedical Engineering, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 August 2025

CITATION: Smith, MM., Melrose, J., 2025. Pentosan Polysulfate, An Anti-Viral Heparinoid, Prevents Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona Virus-2 Infection and Treats Symptoms of Long Coronavirus Disease. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6735

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6735

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

This study highlights the roles of pentosan polysulfate as a decoy anti-viral prophylactic that prevents severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection. PPS also has multifunctional cell and tissue protective properties relevant to the treatment of the symptoms produced by long COVID disease. PPS has heparan sulfate (HS)-like properties, a key functional component of the lung glycocalyx. The glycocalyx is also rich in hyaluronan which has important cell shielding and cell regulatory properties. A healthy glycocalyx prevents access of viral particles to cell surface heparan sulfate-proteoglycans (syndecan, glypican) which act as viral receptors. Pentosan polysulfate promotes hyaluronan synthesis by many cell types, ensuring cells are surrounded by a healthy protective glycocalyx. Hyaluronan, however, has a relatively short biological half-life and is susceptible to degradation by hyaluronidases that are upregulated by inflammatory cytokines in acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID-19 disease. This results in the glycocalyx becoming degraded and endothelial cells dysfunctional in COVID-19 disease. Prevention of viral interaction with the host cell surface intercepted by pentosan polysulfate, a decoy viral binding prophylactic agent, blocks viral interaction with cell-surface heparan sulfate, preventing viral interactions with other cell surface receptors such as neuropilin-1 and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Co-operation between heparan sulfate, neuropilin-1 and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 facilitates the infection of host cells with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, thus if the initial interaction with heparan sulfate is blocked this prevents the subsequent viral interactive stages. Pentosan polysulfate also has multifunctional cell and tissue protective properties, broad anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and inhibits cytokine production in acute respiratory disease syndrome. Pentosan polysulfate inhibits p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κB activation, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β and interleukin-6. Furthermore, pentosan polysulfate is processed by enzymes of the gut microbiome into prebiotic xylo-oligosaccharides that preserve gut health and combat gut dysbiosis seen in COVID-19 disease. Studies are thus warranted to fully assess pentosan polysulfate as an anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 prophylactic agent and its multifunctional cell and tissue protective properties. Furthermore, from a practical and economic point of view, treatment with pentosan polysulfate would offer substantial cost-benefit advantages over conventional vaccine and antibiotic treatments and could also be used in an adjunctive capacity with existing therapies, offering flexibility in its use.

Keywords:

Pentosan polysulfate; SP54; Neuropilin-1; angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; Heparan sulfate; SARS-CoV-2; HIV; Herpes simplex; Dengue virus; Papillomavirus.

1. Introduction

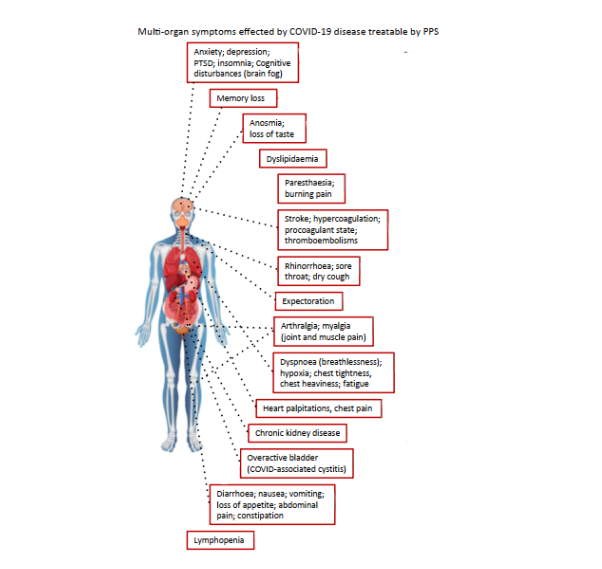

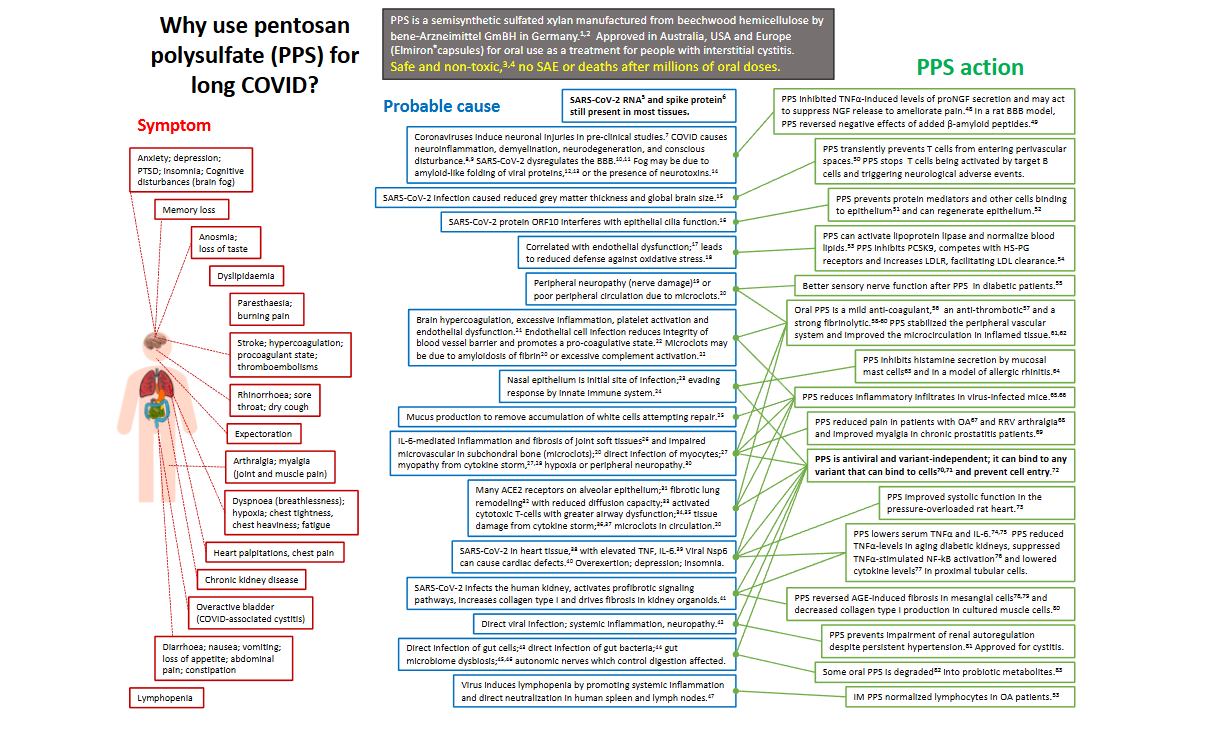

The aim of this study was to highlight the roles of pentosan polysulfate (PPS), a semisynthetic heparinoid, as a decoy anti-viral prophylactic in the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection of host cells. The multifunctional cell and tissue protective properties of PPS are also described illustrating how PPS may be employed to treat the multi-parameter symptomatology that characterises long COVID disease (

).

1.1 COVID-19 IS A PANDEMIC VIRAL DISORDER OF GLOBAL IMPACT

COVID-19 is a pandemic disease that emerged in Wuhan, China in late 2019 with the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), a single strand RNA virus that is 96.2% identical in genomic sequence to the bat CoV RaTG13 virus. SARS-CoV-2 is highly transmissible through aerosols, droplets, fomite affected surfaces or direct skin contact. Historically, SARS-CoV-2 has demonstrated an unprecedented infectious global profile and has undergone rapid evolutionary mutational changes as part of its natural life cycle into several variants which avoid immune detection. Some of these SARS-CoV-2 variants bind more efficiently and with greater rapidity to respiratory epithelial cells, rendering these viral forms significantly more infectious. The Omicron variant is currently a dominant global variant, 99% of all variants circulating in the U.S. are mutations of Omicron, most commonly EG.5 (24% of all SARS-CoV-2 strains) and FL 1.5.1 (14%). A distinctive feature of these Omicron variants is a change in their infective profiles displaying more effective infection of the nose and throat rather than the original Wuhan and Delta variants which primarily infected the lungs. Respiratory distress is a prominent feature of SARS-CoV-2 infections, but other organ systems can also be affected including the brain, liver, heart, and kidney. Symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection include fever, anosmia, ageusia, dry cough, fatigue, breathlessness, hair loss and so-called brain-fogging with a decline in problem solving capability, cognition, ability to concentrate, negative neurological impact and an increase in long-term anxiety. These symptoms can be mild, moderate or severe and a fatality rate of 1 in 100 is reported depending on the co-morbidities that patients display; these can significantly impact the severity of COVID-19. A global systematic review of 76 studies that examined a total of 17,860,001 patients across 14 countries showed that age >75 years, male sex, severe obesity, lymphopenia, and cancer increased the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on health and well-being.

Viral recombination is a normal part of the viral life cycle but results in an extremely wide spread in epitope presentations and these continually undergo changes in structure. This makes it problematic to raise vaccines or antibodies to current infectious viral strains and these require continual updating putting enormous strain on viral treatment resources. In the present study we have shown how PPS can inhibit all viral classes by blocking the interaction of virion particles with cell surface HS and we propose that this has considerable merit as a preventative approach to treatment of potential infections by SARS-CoV-2 but is also applicable to other viral classes. Furthermore, PPS is a pleotropic cell and tissue protective agent as we have outlined in this review and is suitable for the treatment of many facets of the varied symptomatology encountered in COVID-19 infected tissues throughout the human body. This is a further strength of PPS as a therapeutic agent for viral conditions.

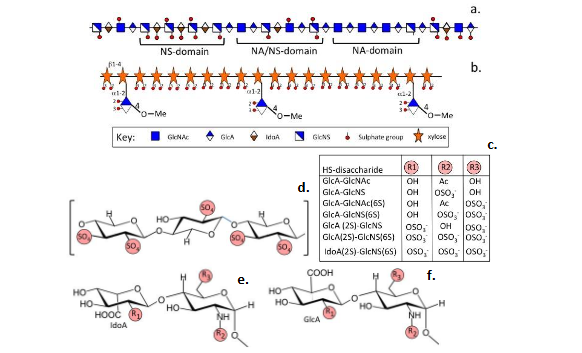

1.2 PENTOSAN POLYSULFATE, A PROPHYLACTIC ANTI-VIRAL PLEOTROPIC CELL AND TISSUE PROTECTIVE AGENT

Pentosan polysulfate is a semi-synthetic sulfated xylan biomimetic heparinoid that has been categorized as a disease modifying anti-arthritic drug (DMOAD). It has a smaller molecular weight than heparan sulfate (HS) or heparin but has a higher charge density and has many properties that mimic HS found on cell surfaces and in extracellular matrix heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) (

).

2. The impact of Coronaviruses on human health and well-being

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are enveloped viruses of the Nidovirales order, Coronaviridae family. Bats, dogs, cats and humans can all be infected with these viruses. Seven species of CoVs have so far been identified, four of these produce relatively mild symptoms of the common cold but severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) and SARS-CoV-2 have a higher impact and can be life-threatening diseases. The SARS-CoV pandemic of 2002-2003 resulted in 774 deaths and 8098 cases of infection distributed over 26 countries. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) emerged ten years later as the sixth coronavirus and resulted in infections across 27 countries in the Middle East, Asia, North Africa and Europe which resulted in 2040 infections and 712 deaths. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the seventh coronavirus (CoV) which has recently emerged resulting in a global health pandemic. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is closely related to Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) but has a far more infectious profile and thus has a significantly greater impact on global human health. As of 19th Sept 2024, 704 million confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in 223 countries and territories, 7 million deaths and 675 million cases of recovery from infection have been reported by Worldometer.

2.1 PREVENTION OF VIRAL INFECTION OF HOST CELLS BY PENTOSAN POLYSULFATE

To infect human cells, viruses must pass a dense layer of carbohydrate (glycocalyx) attached to the cell surface. Several viruses, including Herpes, HIV and other coronaviruses, bind to HS during this infection phase. HS and ACE2 are necessary for SARS-CoV-2 infection and Nrp-1 has additional roles to play as a co-receptor in this infective process. Molecular modeling, atomic force measurements and X-ray crystallography have shown that SARS-CoV-2 HS binds the Spike S1 receptor binding domain (RBD). Infection can be prevented by enzymatic removal of HS from the cell surface, demonstrating the importance of HS in the initial viral attachment phase. Exogenous heparin, LMW heparin and PPS block coronavirus infections in lab-grown cells by binding to the isolated SARS-CoV-2 viral particles dispersed in biological fluids and this prevents them from entering and infecting host cells. A GAG-binding site in the N-terminal domain (NTD) of Spike protein in residues 241-246 binds HS. Prophylactic administration of HS oligosaccharides also bind to this site and prevent productive associations between Spike protein and ACE2 showing how PPS blocks SARS-CoV-2 infection. Molecular dynamic simulations of the Spike trimer interaction with HS dodecasaccharides (and PPS) indicate that when attached to this HS binding site these GAG components span the RRAR (CendR) furin cleavage site interfering with Spike protein interactions with cell surface receptors essential for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Use of heparin in-vitro can block this infective process in epithelial cells. Polysulfates block SARS-CoV-2 uptake into cells showing electrostatic interactions are important in this process explaining why PPS inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection of host cells. Biochemical, biophysical, and genetic studies show HS induces an open conformation in S protein required for binding to ACE2, a high degree of coordination between host cell HS and S protein asparagine-linked glycans enables ACE2 binding and host cell infection. Prophylactic use of PPS disrupts this interaction with cell surface HS and prevents host cell infection. SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein is proteolytically processed by transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2) and furin produced by host cells to prime the S1 domain for binding to ACE2. Transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2), a respiratory and gastrointestinal membrane anchored protease, plays a crucial role in the activation of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Endogenous serine protease inhibitory proteins in tissues may have a protective role to play in the prevention of this protease mediated remodeling of SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein required to facilitate its interaction with ACE2. Small drug inhibitors (Camostat, Nafamostat, and Bromhexine) have been repurposed from anti-tumor applications to inhibit TMPRSS2 mediated SARS-CoV-2 S protein priming. Entry of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells via the receptor binding domain (RBD) of S protein after the S1 and S2 subunits dissociate from each other by the action of TMPRSS2 allow conformational rearrangement and prime it for interaction with the host cell. Furin, a type 1 membrane protease, also cleaves between S1 and S2 in SARS-CoV-2 S protein to facilitate binding to ACE2 and viral membrane fusion with the host cell plasma membrane, effecting internalisation of SARS-CoV-2. Transmembrane protease, serine 2 is part of a mucous secretory network highly upregulated in inflammation by interleukin-13. Interleukin-13 (IL-13) and viral infection also mediate effects on ACE2 expression in the airway epithelium with interferon mediated responses to respiratory viruses highly upregulating ACE2 expression. Moreover, some viruses synthesize their own TMPRSS2 and this also has roles in viral activation. While ACE2 is considered to be the primary host receptor in SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV infections these related viruses have vastly different infection rates, suggesting the involvement of factors in addition to ACE2 that promote SARS-CoV-2 infection. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-1 (SARS-CoV-1) and SARS-CoV-2 both bind to the ACE-2 receptor on host cells, however the latter is considerably more infectious, utilising multiple factors to achieve this higher infection rate. Neuropilin-1 (NRP-1) is another host cell co-receptor that SARS-CoV-2 also uses for cellular attachment. Furin generates a C-end rule motif (CendR) in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and this interacts with a CendR receptor in Nrp-1 promoting the internalisation of CoV-2 viral particles by endocytosis. The greater infective efficiency of the Omicron CoV-2 variant suggests it utilises these additional cell surface motifs to infect host cells. Cell surface HS is used by many viruses as a docking module in host cell infection. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) are endocytic receptors that viruses use for cell entry. NRP-1 is also an endocytic receptor. Herpes simplex, hepatitis, papilloma, flaviviruses and respiratory syncytial virus all utilize multiple cell surface receptors as part of their internalization strategy to infect host cells. Viruses do not bind to the non-sulfated HA component of the glycocalyx, and this acts as a barrier to viral penetration. It has been proposed that COVID-19 is an endothelial disease brought on by the cytokine storm of ARDS that produces destructive changes in the endothelial cell glycocalyx. Significantly, binding of viral particles to PPS in biological fluids prevents them from interacting with the HS chains of syndecan (SDC) or glypican (GPC) to gain access to the Nrp-1 or ACE2 receptors on host cells.

Table I

ACE2, cell surface HSPGs and Nrp-1 interact with SARS CoV-2 Spike protein facilitating viral entry to host cells.

| Receptor | Physiological properties | Evidence for roles as a SARS CoV-2 receptor |

|---|---|---|

| HS | Cell-ECM signaling, Cell adhesion, Cell growth factor and cytokine interactions | Direct interaction of HS with S glycoprotein in ECM, GAG microarray, co-precipitation experiments. Enzymatic removal of HS or HS knockdown results in reduced SARS CoV-2 infection levels. |

| ACE2 | Regulation of blood pressure | Cryo EM images/ X ray crystallography demonstrate ACE2 bound to S RBD. ACE2 over-expression in cells results in enhanced CoV-2 infection. Human ACE2 over-expression in mice results in enhanced CoV-2 infection. Inhibition of SARS CoV-2 infection is evident in ACE2 knockout cells. |

| Nrp-1 | Regulation of neural network development and angiogenesis in tissue development | Demonstration of binding of Nrp-1 to Furin generated C-end rule (CendR) motif in Spike protein. Overexpression of Nrp-1 in cells results in enhanced SARS CoV-2 infection. Nrp-1 KO results in a reduced SARS CoV-2 infection. |

Table II

Cell surface HS Proteoglycans that act as viral receptors.

| HSPG receptor | Viruses |

|---|---|

| Syndecan-1 | Hepatitis C virus |

| Syndecan-2 | Hepatitis B virus, Dengue virus strain DEN2 16681 |

| Syndecan-3 | HIV-1 |

| Syndecan-4 | Adeno-Associated Virus 9, Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus |

| Glypican-5 | Hepatitis B and D viruses |

| Syndecans | Porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus, Papilloma viruses. |

| Syndecan | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Syndecans | HIV-1 |

2.2 CELL SURFACE GLYCOSAMINOGLYCANS AND VIRAL INFECTION OF HOST CELLS.

2.2.1 Anionic anti-viral compounds

Anionic polysulfate GAGs have inhibitory effects on host cell infection with multiple viruses including SARS-CoV-2 and AIDS; PPS has been proposed as a drug for the prevention of infection with AIDS and SARS-CoV-2. It has been proposed that these compounds should be administered as aerosols inhaled into lung tissues to increase their potency. Administration of sulfated hyaluronan derivatives delivered by aerosol prolong the survival of K18 ACE2 mice infected with a lethal dose of SARS-CoV-2. PPS (SP 54), a low molecular weight sulfated polysaccharide is one of the most active in vitro inhibitors of retrovirus-specific reverse transcriptase and is a selective anti-HIV and anti-SARS-CoV-2 agent in vitro. Polysulfated polyxylan (HOE/BAY 946) completely inhibited syncytium formation induced by HIV infection of T-lymphocytes as well as viral replication and inhibited HIV reverse transcriptase. Furthermore, a drastic decrease in the release of viral particles in HIV infected U937 pro-monocytic cells was also elicited by HOE/BAY 946, this increases membrane hydrophobicity of human lymphocytes and specifically suppresses HIV-protein synthesis, and also inhibits HIV replication in human monocytes/macrophages. The pharmacokinetics of intravenous HOE/BAY 946 has been examined in HIV patients. Sulfated polysaccharides have also been shown to inhibit lymphocyte-to-epithelial transmission by HIV-1.

2.3 SEVERE ACUTE RESPIRATORY SYNDROME VIRUS-2 VARIANTS

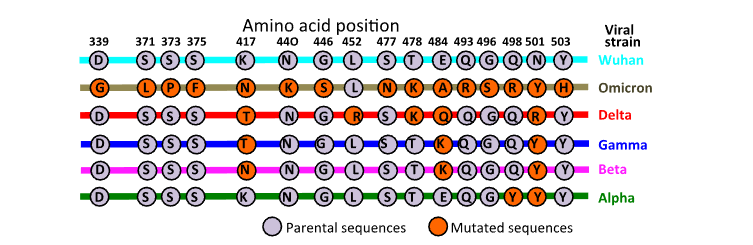

A highly virulent Delta SARS-CoV-2 variant (B 1.617.2) emerged in India in 2020 becoming the dominant global strain. On 24 November 2021, a further highly infectious SARS-CoV-2 variant (B.1.1.529/BA.1) was reported, this has also had a significant global impact displacing the delta variant as the dominant SARS-CoV-2 strain. The World Health Organization Technical Advisory Group on SARS-CoV-2 Viral Evolution designated this emergent CoV variant as B.1.1.529, the fifth Coronavirus variant and named it Omicron. Several Omicron variants have emerged since then with the BA-4 and BA-5 variants becoming firmly established. Vaccines raised to the original Wuhan strain of SARS-CoV-2 offer incomplete coverage of these variants and multiple COVID-19 re-infections two or three times have been reported. This emphasizes the need to develop alternative preventative strategies to prevent COVID-19 infections rather than vaccines or antibodies that treat the symptoms. It is not known to what extent all of the symptoms of long COVID disease are treatable or whether full recovery is possible, however besides acting as a viral anti-infective agent, PPS also treats COVID-19 disease symptomatology.

The BA-4 and BA-5 Omicron variants are the most infectious forms of SARS-CoV-2 and are of major concern; their greater infectivity is related to 32 mutations in their S protein compared to the original Wuhan CoV-2 strain, 15 of these mutations specifically affect the CoV-2 RBD of S protein. The high infective rate of the Omicron variants suggest these utilise a more effective range of cell surface binding motifs in addition to the ACE2 receptor and Nrp-1. A further Omicron sub-variant, a so-called second generation sub-variant, BA.2.75 has emerged in India, unofficially named Centaurus and has been detected in Germany, The Netherlands, Japan, UK, US, Australia and New Zealand. Two mutations in the BA.2.75 variant (G446S and R493Q) allow it to escape immune detection and to bind more strongly to the ACE2 receptor, it is predicted that this increases its infectivity. Prior COVID-19 immunizations may limit the infectiousness of this new sub-variant however it is not known how effective pre-existing antibody preparations will be against this new Omicron variant.

2.4 MUTATIONS IN S1 SPIKE GLYCOPROTEIN IN SEVERE ACUTE RESPIRATORY SYNDROME VIRUS-2 VARIANTS.

Examination of amino acid sequences in the S1 glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 variants demonstrates significant substitutions of native SARS-CoV-2 sequence which partly explains the waning effectiveness of vaccines and therapeutic antibodies in the treatment of COVID-19 disease and the evasion of immune detection of these variant forms of SARS-CoV-2. Of the viral strains of SARS-CoV-2 so far identified, the Omicron strain has the highest number of S1 RBD substitutions (

).

Table III.

A. Viruses that gain access to cells through interaction with cell surface HS and B. antiviral sulfated polysaccharides that block such viral interactions.

| Virus | Docking module |

|---|---|

| Viruses that utilize HS or related GAGs for infection of host cells | |

| Adeno-associated virus 2 | HS |

| Adeno associated virus serotype 3B | HS |

| Akabane and Schmallenberg Viruses. | HS |

| Chikungunya Virus Strains | Sulfated GAGs |

| Coxsackievirus B3 variant, Coxsackievirus A16, B4 | N- and 6-O-sulfated HS |

| Dengue Viruses | HS |

| Duck Tembus virus | HS |

| Ebola virus | HS |

| Echovirus 5 | HS |

| Enterovirus A71 | HS |

| Filovirus | HS |

| Henipavirus | HS |

| Hepatitis B virus | HSPG |

| Hepatitis delta virus | HSPG |

| Hepatitis C virus | HS, HS-proteoglycans |

| Human herpes virus 8 | HS |

| Herpes simplex virus type 1 | HS |

| Human meta pneumonia virus | HS |

| Human Parechovirus | HS |

| Japanese encephalitis virus | HS |

2.2.2 Inhibition of viral attachment to host cells using sulfated polysaccharides

| Virus | Blocking polysaccharide |

|---|---|

| African swine fever virus | PPS and Sulfated polysaccharides |

| Herpes simplex, Cytomegalovirus, Vesicular stomatitis virus, Sindbis virus HIV | PPS and Sulfated polysaccharides |

| T cell leukemia virus type-1 | PPS |

| Chikungunya virus | PPS |

| Ross river virus | PPS |

| SARS-CoV-2 | PPS, Polysulfates, heparin, enoxaparin |

3. Anti-inflammatory and tissue protective properties of pentosan polysulfate

Pentosan polysulfate has anti-inflammatory properties in knee OA, reducing joint swelling and pain and has reno-protective effects in kidney injury, nephrectomy and diabetic nephropathy. Pentosan polysulfate is also effective against arthritogenic alphaviruses such as Ross River virus (RRV) and chikungunya virus (CHIKV) which cause cartilage destruction, crippling pain and joint inflammation. Pentosan polysulfate increases production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and reduces production of proinflammatory cytokines, modulates growth factor signaling and lymphocyte activation and reduces inflammatory infiltrates in joint fluids in chikungunya infected mice. Pentosan polysulfate has systemic and local anti-inflammatory activity in post-acute pulmonary inflammation in an influenza virus A induced pulmonary inflammation model. The beneficial effects of PPS are due to a combination of its anti-viral and anti-inflammatory properties. Pentosan polysulfate also supports tissue repair processes in the degenerate IVD, representing part of its pleotropic tissue and cell protective properties.

3.1 THE HYPERCOAGULATIVE STATE OF COVID-19 IMPAIRS PLATELET FUNCTION AND TISSUE REPAIR RESPONSES, WEAKENING NORMAL LUNG FUNCTION

Corona virus-2 infected patients that develop a severe pro-inflammatory state are also frequently associated with a procoagulant endothelial phenotype that produces an elevation in fibrinogen and D-dimer/fibrin(ogen) degradation products associated with systemic hypercoagulability. Fibrinogen D-dimer levels positively correlate with mortality rates in COVID-19 patients and lead to arterial thrombotic events including stroke, ischemia and microvascular thrombotic events in the pulmonary vascular beds. Heparan sulfate is a critical regulator of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif (ITIM) receptor G6b-B-R that regulates platelet production and activation. Binding of G6b-B-R to the HS side chains of perlecan and multivalent heparin inhibits platelet and megakaryocyte function by inducing downstream signaling via the protein tyrosine phosphatases Shp1 and Shp2. SARS-CoV-2 initiates programmed cell death in platelets thus G6b-B-R has important roles to play maintaining platelet levels in wound healing responses. Perlecans interaction with G6b and G6b-R regulates fibrotic changes in tissues produced by excessive levels of platelet activation. Perlecan HS also regulates cell adhesion, proliferation and growth factor signaling in tissue repair responses in tissue homeostasis and optimal tissue function, features mimicked by PPS.

3.2 A DYNAMIC BALANCE BETWEEN THE FIBRINOLYTIC AND COAGULATION SYSTEMS IS CRITICAL TO NORMAL LUNG FUNCTION AND HOMEOSTASIS.

The fibrinolytic and coagulation system are interconnected however in COVID-19 can be overwhelmed by a hypercoagulative state that prevails. Plasmin is a major clot dissolving fibrinolytic enzyme produced with elevated levels of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) which in turn is regulated by plasminogen activator inhibitors-1 and -2 (PAI-1, PAI-2). Autopsies of COVID-19 fatalities shows thrombosis, micro-angiopathy, haemorrhage and alveolar damage. The dyslipidemia displayed by COVID-19 patients results in abnormally high levels of low density lipoproteins (LDLs) and low levels of high density lipoproteins (HDLs) in serum.

3.3 LUNG HEPARAN SULFATE PROTEOGLYCANS AND THEIR CELL REGULATORY PROPERTIES

Cell surface HSPGs in the lung are growth factor coreceptors binding these through HS and core protein interactions. Instructive interactions with growth factors, morphogens, chemokines and ECM components, regulate cell adhesion, proliferation, migration, and differentiation, regulating pathophysiological processes in tissue development and repair, inflammation, infection, and tumor development. HS-proteoglycans in the lung have instructive roles critical to regulation of tissue development, organ structure, and the control of resident cell populations. Pikachurin, agrin, perlecan are HSPG components of the lung interactome with essential roles in lung development, homeostasis and function and roles in tissue fibrosis in lung disease. Fragmentation of lung ECM components due to endogenous protease activity or by proteases produced by an influx of inflammatory cells in lung disease leads to the release of bioactive protein fragments (matricryptins, matrikines) which can regulate cell metabolism. Matrikines have been identified with tissue repair properties. While ACE2 is the primary receptor for SARS-CoV-2 entry other cell surface and ECM proteins may also bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD such as perlecan LG3 and may potentially enhance RBD-ACE2 interactions representing a potential therapeutic target. Proteoglycans embedded in the vascular endothelial glycocalyx, regulate the activity of cytokines and inflammatory responses but are proteolytically cleaved in inflammatory diseases and modulate pathological inflammatory responses. Soluble forms of SDC-1, SDC-3 and BGN are anti-inflammatory, suppress proinflammatory cytokine expression and leukocyte migration, and induce autophagy of proinflammatory M1 macrophages. However, soluble versikine, SDC-2, mimecan and DCN are proinflammatory increasing inflammatory cytokine synthesis and leukocyte migration. This contrasts with SDC-4 and perlecan which have anti-inflammatory properties promoting tissue repair. Glypicans also regulate Hh and Wnt signaling in systemic inflammation. Collectively, vascular endothelial glycocalyx-derived SDC-1-4 ectodomains, BGN, versikine, mimecan, perlecan, GPC and DCN are thus of therapeutic potential in the regulation of cytokine and leukocyte responses in lung inflammatory diseases. Pentosan polysulfate down regulates the secretion of a range of inflammatory cytokines and has potent anti-oxidant activity. Both of these properties exert protective properties on cells and preserves tissue function.

4. Depolymerisation of HA in COVID-19 disease.

4.1 CELL MIGRATION-INDUCING AND HYALURONAN-BINDING PROTEIN (CEMIP, KIAA1199) IS A DEAFNESS GENE LINKED WITH DEPOLYMERISATION OF HYALURONAN

KIAA1199 knockdown abolishes HA degradation by human skin fibroblasts, cellular transfection of KIAA1199 cDNA confers an ability to catabolize HA in an endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase-dependent manner. The enhanced degradation of HA that occurs in synovial fibroblasts in OA and RA correlates with elevated KIAA1199 expression and can be abrogated by knockdown of KIAA1199.

4.2 ROLES FOR ENDOTHELIAL CELLS AND HYALURONAN IN TISSUE MORPHOGENESIS AND EXTRACELLULAR MATRIX REPAIR

Hyaluronan promotes proliferation and migration of many cell types, and has important roles in tissue morphogenesis, wound healing, inflammation, angiogenesis, and tissue repair processes. Endothelial cells are responsive to HA oligosaccharides which stimulate proliferation, migration, new vessel formation and tissue repair responses. Pulmonary stromal fibroblasts and myofibroblasts synthesise HA contributing to the deposition of HA in the endothelial glycocalyx, COVID-19 has been proposed to be an endothelial cell dysfunction disease. Angiotensin converting enzyme is highly expressed by endothelial cells, ACE2 has critical roles that impact on the progression of COVID-19 disease.

5. A summation of the pleotropic cell and tissue protective properties of Pentosan polysulfate

Supplementary Figure 1 summarises the major changes that have been documented in COVID-19 and studies which have utilized PPS to treat the multiple symptoms which arise from viral infection. Besides having the ability to prevent attachment of a large range of viruses to host cells which occur through cell surface HS interactions (Table II, Table III) PPS also has many cell and tissue protective properties. These include application in the treatment of cystitis and painful bowel disease, as a tissue protective enzyme inhibitor, promotion of cartilage and IVD repair, healing of OA cartilage and the degenerate IVD. PPS has been used in bioscaffolds in tissue engineering applications. PPS regulates Complement activation, coagulation/fibrinolysis, thrombocytopenia, and induces HA production by many cell types. Pentosan polysulfate inhibits NGF production by osteocytes which reduces bone pain in OA/RA and promotes lipid removal from subchondral blood vessels engorged with lipid in OA/RA reducing pain in these conditions. Regulation of cytokine and inflammatory mediator production by PPS in ARDS reduces inflammation in tissues. PPS also has anti-viral activity and is an anti-tumor agent in a number of cancers.

5.1 PENTOSAN POLYSULFATE AND THE GUT MICROBIOME

The gut microbiome is disturbed in COVID-19 disease, with alterations in cell populations and imbalance in beneficial symbionts and opportunistic pathogens. Xylan is the second most abundant plant carbohydrate biomass found in nature. Accumulated evidence shows that xylans interact with gut microbiota in a beneficial way. Humans cannot digest xylans but they act as bulking material aiding in the throughput of digested food items through the gut. The gut microbiome produce a number of xylanolytic enzymes that allow the gut microbiome to utilize xylans as a nutrient source, the generated xylo-oligosaccharides have pre-biotic properties that aid in gut homeostasis countering the gut dysbiosis that occurs in COVID-19 disease. Endoxylanases produced by the gut microbiota generate xylo-oligosaccharides promoting beneficial symbiont microbes such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus populations in the human gut improving mucosal health and immune function and inhibit colonization of the gut by pro-inflammatory bacteria such as Salmonella sp. This improves gut barrier properties, and plasma lipid levels attenuating pro-inflammatory effects of a high fat diet and decreases blood LPS levels and the damaging effects of IL-1β and IL-13.

6. Multi-organ involvement in Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection

SARS-CoV-2 is implicated in the clinical pathology of multiple organs and organ systems. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 canonical mediators, ACE2, and TMPRSS2 are assisted by other coronavirus-associated receptors and factors, including basigin (BSG/CD147), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4/CD26), cathepsin B/L, furin, interferon-induced transmembrane protein (IFTM1-3) and Nrp-1. The localization of these SARS-CoV-2 receptors, proteases, and genes involved in coding proteins that drive viral pathogenesis predisposes to SARS-CoV-2 infection in a number of tissues, COVID-19 infection thus involves the hACE2 receptor and its co-receptors Nrp-1 and DPP4/CD26 which engage with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

6.1 HEMOLYSIS IN COVID 19 INFECTED LUNG TISSUES

Hemolysis is a common feature of COVID-19 infected tissues, fibrotic changes in tissues also occurs resulting in a reduction in tissue elastic properties and lung function. Pro-coagulant activity also results in thrombus formations in tissues impairing their functional properties. This leads to further detrimental effects on these tissues with free heme release resulting in oxidative stress, local generation of oxygen free radicals and mitochondrial and ER distress, leukocyte recruitment, vascular permeabilization, platelet and Complement activation, thrombosis, and fibrosis leading to impaired lung function. Platelets initiate blood clotting, severely affected COVID-19 patients display a high incidence of hypercoagulation in the lungs and brain. Plasma fibrinogen levels are also elevated with advancing age, high cholesterol, being female, menopause, obesity, smoking, inactivity and stress. Most of these features are putative risk factors for COVID-19. Heparin treatment of COVID-19 patients displaying enhanced coagulation levels results in an improved prognosis however heparin will only prevent thrombus formation and will not dissolve existing fibrin clots, thus is palliative and not curative. Prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection of host cells by PPS represents a more effective treatment strategy and has the added advantage of minimizing inflammatory cytokine production and exacerbation of inflammatory conditions in tissues. Heme is a prosthetic group with functional roles in a wide variety of heme proteins such as hemoglobin and the cytochromes. Release of free heme in injured lung tissues promotes adhesion molecule expression, leukocyte recruitment, vascular permeabilization, platelet activation, complement activation and thrombosis. Heme, however, can be degraded by the anti-inflammatory enzyme heme oxygenase (HO-1) generating biliverdin/bilirubin, iron/ferritin and carbon monoxide. Free heme promotes lung inflammation in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Heme oxygenase -1 has anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory properties and may represent a specific means of targeting hemolysis therapeutically in COVID-19 disease.

6.2 COVID AND COGNITIVE DECLINE

COVID-19 infected patients frequently exhibit neurological symptoms of anosmia and fatigue and long-term neurological deficits post-infection such as cognitive decline and brain-fogging. Positron emission tomography (PET) and SPECT (Single-photon emission computed tomography) molecular imaging techniques have been used to shed light on how COVID-19 affects human brain structure. Human brain structure is affected by long COVID-19 disease even after recovery of respiratory function and has been referred to as Post COVID Syndrome. It is not known how long such neurological deficits will persist in cases of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection following recovery of respiratory function however reports of a reduction in IQ and altered immune regulation in young children affected by even very mild COVID-19 respiratory disease are particularly concerning. Long-term CNS neuro-inflammation following COVID-19 infection in children may deleteriously affect brain development. Disturbing reports are emerging of learning difficulties and a decline in the educational status of 9 year olds affected by COVID-19, an effect which may be exacerbated in individuals who also display underlying neurological deficits.

7. Conclusions

Use of PPS as a prophylactic that intercepts SARS-CoV-2 virion particles in the glycocalyx prevents their binding to cell surface HS in all viral strains and is not impeded by point mutations arising from recombination as part of the natural viral life-cycle. SARS-CoV-2 possesses 24 spike glycoproteins per virion particle which have central roles in binding to cell surface ACE2 facilitating viral entry into host cells. This occurs through the RBD of spike protein however this is buried within the S1 domain which is exposed by a conformational change upon interaction with cell surface HS. PPS prevents such HS interactions occurring and viral infection and warrant further investigation. PPS is effective against all classes of viruses and its anti-viral properties are not diminished by viral mutations. The emergence of a further bat coronavirus, HKU5-CoV-2 related to SARS-CoV and of a mink respiratory coronavirus (MRCoV) related to MERS and SARS-CoV2 indicates that due diligence is essential. PPS would be expected to be an effective blocking agent for these new CoV strains, however vaccines or antibodies have yet to be developed. It may thus be a prime time to adopt PPS in preventative anti-viral strategies.

Disclosures

JM has received consultancy fees from Arthropharm-Sylvan Pharmaceutical Ltd. MMS is clinical research director at Arthropharm-Sylvan Pharmaceutical Ltd. The authors have no conflicts to report.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

This study was funded by the Melrose Personal Research Fund, Sydney, Australia. The contributions of the many scientists who have characterized the properties of PPS in laboratory studies and pre-clinical trials and whose work is reviewed in this manuscript is acknowledged.

Author contributions

JM and MMS shared in conception of the study and shared in the writing and editing of this manuscript. JM and MMS both shared in the preparation of the figures. Both authors accepted the final version of the manuscript.

References

1 Johnston, C., Hughes, H, Lingard, S, Hailey, S, Healy, B. Immunity and infectivity in covid-19. 378, e061402 (2022).

2 Yisimayi, A., et al., Repeated Omicron exposures override ancestral SARSCoV-2 immune imprinting. Nature 625, 148-156 (2024).

3 Cele, S., et al., Omicron extensively but incompletely escapes Pfizer BNT162b2 neutralization. Nature 602, 654-656 (2022).

4 Kaku, Y., et al., Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP.2 variant. Lancet Infect Dis (2024).

5 Plante, J. A., et al., Spike mutation D614G alters SARS-CoV-2 fitness. Nature 592, 116-121 (2021).

6 Lopes-Pacheco, M., Silva, PL, Cruz, FF, Battaglini, D, Robba, C, Pelosi, P, Morales, MM, Caruso Neves, C, Rocco, PRM. Pathogenesis of Multiple Organ Injury in COVID-19 and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Front Physiol 12, 593223 (2021).

7 Mokhtari, T., Hassani, F, Ghaffari, N, Ebrahimi, B, Yarahmadi, A, Hassanzadeh, G. COVID-19 and multiorgan failure: A narrative review on potential mechanisms. J Mol Histol 51, 613-628 (2020).

8 Zaim, S., Chong, JH, Sankaranarayanan, V, Harky, A. COVID-19 and Multiorgan Response. Curr Probl Cardiol 45, 100618 (2020).

9 Narayanan, S., Jamison, DA, Guarnieri, JW et al. A comprehensive SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 review, Part 2: host extracellular to systemic effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Hum Genet 32, 10-20 (2024).

10 Tang, D., Comish ,P, Kang, R The hallmarks of COVID-19 disease. PLoS Pathog 16, e1008536 (2020).

11 Menon, N., Mohapatra, S. The COVID-19 pandemic: Virus transmission and risk assessment. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health 28, 100373 (2022).

12 Smith, M., Melrose, J. Pentosan Polysulfate Affords Pleotropic Protection to Multiple Cells and Tissues. . Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 16, 437 (2023).

13 Smith, M., Hayes, AJ, Melrose, J. Pentosan Polysulfate, a Semisynthetic Heparinoid Disease-Modifying Osteoarthritic Drug with Roles in Intervertebral Disc Repair Biology Emulating the Stem Cell Instructive and Tissue Reparative Properties of Heparan Sulfate. Stem Cells Dev 31, 406-430. doi: 410.1089/scd.2022.0007 (2022).

14 Fehr, A., Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methoda Mol Biol 1282, 1-23 (2015).

15 Rabaan, A., Al-Ahmed,SH, Haque, S, Sah, R, Tiwari, R, Malik, YS, Dhama, K, Yatoo, MI, Bonilla-Aldana, DK, Rodriguez-Morales, AJ. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-COV: a comparative overview. Infez Med 28, 174-184 (2020).

16 Rabaan, A., Al-Ahmed,SH, Haque, S, Sah, R, Tiwari, R, Malik, YS, Dhama, K, Yatoo, MI, Bonilla-Aldana, DK, Rodriguez-Morales, AJ. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-COV: a comparative overview. Infez Med 28, 174-184 (2020).

17 Chafekar, A., Fielding, BC. MERS-CoV: understanding the latest human coronavirus threat. Viruses 10, 93 (2018).

18 Worldometer. Coronavirus death toll. https://http://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/coronavirus-death-toll/ (2022).

19 Bhat, E., Khan, J, Sajjad, N, Ali, A, Aldakeel, FM, Mateen, A, Alqahtani, MS, Syed, R. SARS-CoV-2: Insight in genome structure, pathogenesis and viral receptor binding analysis – An updated review. Int Immunopharmacol 95, 107493 (2021).

20 Guney, C., Akar, F. Epithelial and Endothelial Expressions of ACE2: SARS-CoV-2 Entry Routes. J Pharm Pharm Sci 24, 84-93 (2021).

21 Kim, S., Jin, W, Sood, A, Montgomery, DW, Grant, OC, Fuster, MM, Fu, L, Dordick, JS, Woods, RJ, Zhang, F, Linhardt, RJ. . Characterization of heparin and severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike glycoprotein binding interactions. Antiviral Res 181, 104873 (2020).

22 Rusnati, M., Urbinati, C, Caputo, A, Possati,L, Lortat-Jacob, H, Giacca, M, Ribatti, D, Presta, M. . Pentosan polysulfate as an inhibitor of extracellular HIV-1 Tat. J Biol Chem 276, 22420-22425 (2001).

23 Tandon, R., Sharp, JS, Zhang, F, Pomin, VH, Ashpole, NM, Mitra, D, McCandless, MG, Jin, W, Liu, H, Sharma, P, Linhardt, RJ. Effective Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Entry by Heparin and Enoxaparin Derivatives. J Virol 95, e01987-01920 (2021).

24 Yu, M., Zhang, T, Zhang, W, Sun, Q, Li,H, Li, JP. Elucidating the Interactions Between Heparin/Heparan Sulfate and SARS-CoV-2-Related Proteins-An Important Strategy for Developing Novel Therapeutics for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Mol Biosci 7, 628551 (2021).

25 Schuurs, Z., Hammond, E, Elli, S, Rudd, TR, Mycroft-West, CJ, Lima, MA, Skidmore, MA, Karlsson, R, Chen, YH, Bagdonaite, I, Yang, Z, Ahmed, YA, Richard, DJ, Turnbull, J, Ferro, V, Coombe, DR, Gandhi, NS. . Evidence of a putative glycosaminoglycan binding site on the glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 spike protein N-terminal domain. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 19, 2806-2818 (2021).

26 Clausen, T., Sandoval, DR, Spliid, CB, Pihl, J, Painter, CD, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection depends on cellular heparan sulfate and ACE2. Cell 183, 1043-1057 (2020).

27 Partridge, L., Urwin, L, Nicklin, MJH, James, DC, Green, LR, Monk, PN. ACE2-Independent Interaction of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein with Human Epithelial Cells Is Inhibited by Unfractionated Heparin. Cells 10, 1419 (2021).

28 Nie, C., Pouyan, P, Lauster, D, Trimpert, J, Kerkhoff, Y, Szekeres, GP, Wallert, M, Block, S, Sahoo, AK, Dernedde, J, Pagel,K, Kaufer, BB, Netz, RR, Ballauff, M, Haag, R. Polysulfates Block SARS-CoV-2 Uptake through Electrostatic Interactions*. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 60, 15870-15878 (2021).

29 Kearns, F., Sandoval, DR, Casalino, L, Clausen, TM, Rosenfeld, MA, Spliid, CB, Amaro, RE, Esko, JD. Spike-heparan sulfate interactions in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Curr Opin Struct Biol 76, 102439 (2022).

30 Bhat, E., Khan, J, Sajjad, N, Ali, A, Aldakeel, FM, Mateen, A, Alqahtani, MS, Syed, R. SARS-CoV-2: Insight in genome structure, pathogenesis and viral receptor binding analysis – An updated review. Int Immunopharmacol 95, 107493 (2021).

31 Guney, C., Akar, F. Epithelial and Endothelial Expressions of ACE2: SARS-CoV-2 Entry Routes. J Pharm Pharm Sci 24, 84-93 (2021).

32 Rusnati, M., Urbinati, C, Caputo, A, Possati,L, Lortat-Jacob, H, Giacca, M, Ribatti, D, Presta, M. Pentosan polysulfate as an inhibitor of extracellular HIV-1 Tat. J Biol Chem 276, 22420-22425 (2001).

33 Tandon, R., Sharp, JS, Zhang, F, Pomin, VH, Ashpole, NM, Mitra, D, McCandless, MG, Jin, W, Liu, H, Sharma, P, Linhardt, RJ. Effective Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Entry by Heparin and Enoxaparin Derivatives. J Virol 95, e01987-01920 (2021).

34 Yadav, R., Chaudhary, JK, Jain, N, Chaudhary, PK, Khanra, S, Dhamija, P, Sharma, A, Kumar, A, Handu, S. Role of Structural and Non-Structural Proteins and Therapeutic Targets of SARS-CoV-2 for COVID-19. Cells 10, 821 (2021).

35 Yuan, H., Wen,HL. Research progress on coronavirus S proteins and their receptors. . Arch Virol 28 (2021).

36 Mahmoud, I., Jarrar, YB. Targeting the intestinal TMPRSS2 protease to prevent SARS-CoV-2 entry into enterocytes-prospects and challenges. Mol Biol Rep doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06390-1 (2021).

37 Cantuti-Castelvetri, L., Ojha, R, Pedro, LD, Djannatian, M, Franz, J, Kuivanen, S, van der Meer, F, Kallio, K, Kaya, T, Anastasina, M, Smura, T, Levanov, L, Szirovicza, L, Tobi, A, Kallio-Kokko, H, Österlund, P, Joensuu, M, Meunier, FA, Butcher, SJ, Winkler, MS, Mollenhauer, B, Helenius, A, Gokce, O, Teesalu, T, Hepojoki, J, Vapalahti, O, Stadelmann, C, Balistreri, G, Simons, M. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science 370, 856-860 (2020).

38 Chekol Abebe, E., Mengie Ayele, T, Tilahun Muche, Z, Asmamaw Dejenie, T. . Neuropilin 1: A Novel Entry Factor for SARS-CoV-2 Infection and a Potential Therapeutic Target. Biologics 15, 143-152 (2021).

39 Daly, J., Simonetti, B, Klein, K, Chen, KE, Williamson, MK, Antón-Plágaro, C, Shoemark, DK, Simón-Gracia, L, Bauer, M, Hollandi, R, Greber, UF, Horvath, P, Sessions, RB, Helenius, A, Hiscox, JA, Teesalu, T, Matthews, DA, Davidson, AD, Collins, BM, Cullen, PJ, Yamauchi, Y. Neuropilin-1 is a host factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science 370, 861-865 (2020).

40 Sajuthi, S., DeFord, P, Li, Y, Jackson, ND, Montgomery, MT, Everman, JL, Rios, CL, Pruesse, E, Nolin, JD, Plender, EG, Wechsler, ME, Mak, ACY, Eng, C, Salazar, S, Medina, V, Wohlford, EM, Huntsman, S, Nickerson, DA, Germer, S, Zody, MC, Abecasis, G, Kang, HM, Rice, KM, Kumar, R, Oh, S, Rodriguez-Santana, J, Burchard, EG, Seibold, MA. Type 2 and interferon inflammation regulate SARS-CoV-2 entry factor expression in the airway epithelium. . Nat Commun 11, 5139 (2020).

41 Zmora, P., Moldenhauer, AS, Hofmann-Winkler, H, Pöhlmann, S. TMPRSS2 Isoform 1 Activates Respiratory Viruses and Is Expressed in Viral Target Cells. . PLoS One 10, e0138380 (2015).

42 Bertram, S., Glowacka, I, Steffen, I, Kühl, A, Pöhlmann, S Novel insights into proteolytic cleavage of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Rev Med Virol 20, 298-310 (2010).

43 Bertram, S., Glowacka, I, Blazejewska, P, Soilleux, E, Allen, P, Danisch, S, et al. . . TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 facilitate trypsin-independent spread of influenza virus in Caco-2 cells. . J Virol 84, 10016-10025 (2010).

44 Muralidar, S., Gopal, G, Visaga, Ambi, S. Targeting the viral-entry facilitators of SARS-CoV-2 as a therapeutic strategy in COVID-19. J Med Virol doi: 10.1002/jmv.27019 (2021).

45 Davies, J., Randeva, HS, Chatha, K, Hall, M, Spandidos, DA, Karteris, E, Kyrou, I. . Neuropilin 1 as a new potential SARS CoV 2 infection mediator implicated in the neurologic features and central nervous system involvement of COVID 19. Mol Med Rep 22, 4221-4226 (2020).

46 Berrou, E., Quarck, R, Fontenay-Roupie, M, Lévy-Toledano, S, Tobelem, G, Bryckaert, M. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 increases internalization of basic fibroblast growth factor by smooth muscle cells: implication of cell-surface heparan sulphate proteoglycan endocytosis. Biochem J 311, 393-399 (1995).

47 Christianson, H., Belting, M. . Heparan sulfate proteoglycan as a cell-surface endocytosis receptor. Matrix Biol 35, 51-55 (2014).

48 Neill, T., Schaefer, L, Iozzo, RV. Decoding the Matrix: Instructive Roles of Proteoglycan Receptors. Biochemistry 54, 4583-4598 (2015).

49 Balistreri, G., Yamauchi, Y, Teesalu, T. A widespread viral entry mechanism: The C-end Rule motif-neuropilin receptor interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118, e2112457118 (2021).

50 Danthi, P., Holm, GH, Stehle, T, Dermody, TS. Reovirus receptors, cell entry, and proapoptotic signaling. Adv Exp Med Biol 790, 42-71 (2013).

51 Inoue, J., Ninomiya, M, Shimosegawa, T, McNiven, MA. Cellular Membrane Trafficking Machineries Used by the Hepatitis Viruses. Hepatology 68, 751-762 (2018).

52 Mikuličić, S., Florin, L. The endocytic trafficking pathway of oncogenic papillomaviruses. Papillomavirus Res 7, 135-137 (2019).

53 Perera-Lecoin, M., Meertens, L, Carnec, X, Amara, A. Flavivirus entry receptors: an update. Viruses 6, 69-88 (2013).

54 Altgärde, N., Eriksson, C, Peerboom, N, Block, S, Altgärde, N, Wahlsten, O, Möller, S, Schnabelrauch, M, Trybala, E, Bergström, T, Bally, M. Binding Kinetics and Lateral Mobility of HSV-1 on End-Grafted Sulfated Glycosaminoglycans. Biophys J 113, 1223-1234 (2017).

55 Egedal, J., Xie, G, Packard, TA, Laustsen, A, Neidleman, J, Georgiou, K, Pillai, SK, Greene, WC, Jakobsen, MR, Roan, NR. . Hyaluronic acid is a negative regulator of mucosal fibroblast-mediated enhancement of HIV infection. Mucosal Immunol 14, 1203-1213 (2021).

56 Li, P., Fujimoto, K, Bourguingnon, L, Yukl, S, Deeks, S, Wong, JK. Exogenous and endogenous hyaluronic acid reduces HIV infection of CD4(+) T cells. Immunol Cell Biol 92, 770-780 (2014).

57 Peerboom, N., Phan-Xuan, T, Moeller, S, Schnabelrauch, M, Svedhem, S, Trybala, E, Bergström, T, Bally, M. Mucin-like Region of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Attachment Protein Glycoprotein C (gC) Modulates the Virus-Glycosaminoglycan Interaction. J Biol Chem 290, 21473-21485 (2015).

58 Turville, S. Blocking of HIV entry through CD44-hyaluronic acid interactions. Immunol Cell Biol 92, 735-736 (2014).

59 Smith, M., Melrose, J. Impaired instructive and protective barrier functions of the endothelial cell glycocalyx pericellular matrix is impacted in COVID-19 disease. J Cell Mol Med 28, e70033. doi: 70010.71111/jcmm.70033. (2024).

60 Libby, P., and Luscher, T. COVID-19 is, in the end, an endothelial disease. Eur Heart J 41, 3038-3044 (2020).

61 Yang, J., LeBlanc, ME, Cano, I, Saez-Torres, KL, Saint-Geniez, M, Ng, YS, et al. . ADAM10 and ADAM17 proteases mediate proinflammatory cytokine-induced and constitutive cleavage of endomucin from the endothelial surface. J Biol Chem 295, 6641-6651 (2020).

62 Baggen, J. e. a. Genome-wide CRISPR screening identifies TMEM106B as a proviral host factor for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Genet https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00805-2 (2021).

63 Liu, L., Chopra, P, Li, X, Bouwman, KM, Tompkins, SM, Wolfert, MA, de Vries, RP, Boons, GJ. Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans as Attachment Factor for SARS-CoV-2. ACS Cent Sci 7, 1009-1018 (2021).

64 Zhang, Q. e. a. Heparan sulfate assists SARS-CoV-2 in cell entry and can be targeted by approved drugs in vitro. Cell Discov 6, 80 (2020).

65 Bao, L. e. a. The pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 in hACE2 transgenic mice. Nature 583, 830-833 (2020).

66 Hoffmann, M. e. a. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 (2020).

67 Lan, J. e. a. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 581, 215-220 (2020).

68 Schneider, W. e. a. Genome-scale identification of SARS-CoV-2 and pan-coronavirus host factor networks. Cell 184, 120-132 (2021).

69 Sun, S. e. a. A mouse model of SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 28, 124-133 (2020).

70 Zhou, P. e. a. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270-273 (2020).

71 Balistreri, G., Yamauchi, Y, Teesalu, T. A widespread viral entry mechanism: The C-end Rule motif-neuropilin receptor interaction. . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118, e2112457118 (2021).

72 Cantuti-Castelvetri, L., Ojha, R, Pedro, LD, Djannatian, M, Franz, J, Kuivanen, S, van der Meer, F, Kallio, K, Kaya, T, Anastasina, M, Smura, T, Levanov, L, Szirovicza, L, Tobi, A, Kallio-Kokko, H, Österlund, P, Joensuu, M, Meunier, FA, Butcher, SJ, Winkler, MS, Mollenhauer, B, Helenius, A, Gokce, O, Teesalu, T, Hepojoki, J, Vapalahti, O, Stadelmann, C, Balistreri, G, Simons, M. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science 370, 856-860 (2020).

73 Shi, Q., Jiang, J, Luo, G. Syndecan-1 serves as the major receptor for attachment of hepatitis C virus to the surfaces of hepatocytes. J Virol 87, 6866-6875. doi: 6810.1128/JVI.03475-03412. (2013).

74 Okamoto, K., Kinoshita, H, Parquet, MDC, Raekiansyah, M, Kimura, D, Yui, K, et al Dengue virus strain DEN2 16681 utilizes a specific glycochain of syndecan-2 proteoglycan as a receptor. J Gen Virol 93, 761-770. doi: 710.1099/ vir.1090.037853-037850. (2012).

75 Tripathi, S., Li, Y, Luo, G. Syndecan 2 proteoglycan serves as a hepatitis B virus cell attachment receptor. J Virol e0079625. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00796-25 (2025).

76 de Witte, L., Bobardt, M, Chatterji, U, Degeest, G, David, G, Geijtenbeek, TB, Gallay, P. . Syndecan-3 is a dendritic cell-specific attachment receptor for HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 19464-19469. doi: 19410.11073/pnas.0703747104. (2007).

77 Hudák, A., Roach, M, Pusztai, D, Pettkó-Szandtner, A, Letoha, A, Szilák, L, et al Syndecan-4 Mediates the Cellular Entry of Adeno-Associated Virus 9. Int J Mol Sci 24, 3141. doi: 3110.3390 /ijms24043141. (2023).

78 Wang, R., Wang, X, Ni, B, Huan, CC, Wu, JQ, Wen, LB, et al Syndecan-4, a PRRSV attachment factor, mediates PRRSV entry through its interaction with EGFR. . Biochem Biophys Res Commun 475, 230-237. doi: 210.1016/j.bbrc.2016 .1005.1084. (2016).

79 Verrier, E., Colpitts, CC, Bach, C, Heydmann, L, Weiss, A, Renaud, M, et al. . A targeted functional RNA interference screen uncovers glypican 5 as an entry factor for hepatitis B and D viruses. Hepatology 63, 35-48. doi: 10.1002 /hep.28013. (2016).

80 Hu, S., Zhao, K, Lan, Y, Shi, J, Guan, J, Lu, H, et al Cell-surface glycans act as attachment factors for porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus. Vet Microbiol 265, 109315. doi: 109310.1010 16/j.vetmic.102021.109315. (2022).

81 Shafti-Keramat, S., Handisurya, A, Kriehuber, E, Meneguzzi, G, Slupetzky, K, Kirnbauer, R. Different heparan sulfate proteoglycans serve as cellular receptors for human papillomaviruses. J Virol 77, 13125-13135. doi: 13110.11128/jvi.13177 .13124.13125-13135.12003 (2003).

82 Shafti-Keramat, S., Handisurya, A, Kriehuber, E, Meneguzzi, G, Slupetzky, K, Kirnbauer, R. Different heparan sulfate proteoglycans serve as cellular receptors for human papillomaviruses. J Virol 77, 13125-13135. doi: 13110.11128/jvi.13177 .13124.13125-13135.12003. (2003).

83 Bermejo-Jambrina, M., Eder, J, Kaptein, TM, van Hamme, JL, Helgers, LC, Vlaming, KE, et al Infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 depend on heparan sulfate proteoglycans. . EMBO J 40, e106765. doi: 106710.115252/embj.2020106765 (2021).

84 Gallay, P. Syndecans and HIV-1 pathogenesis. Microbes Infect 6, 617-622. doi: 610.1016/j.micinf .2004.1002.1004. (2004).

85 Bobardt , M., Saphire, AC, Hung, HC, Yu, X, Van der Schueren, B, Zhang, Z, et al Syndecan captures, protects, and transmits HIV to T lymphocytes. Immunity 18, 27-39. doi: 10.1016/s1 074-7613(1002)00504-00506. (2003).

86 Saphire, A., Bobardt, MD, Zhang, Z, David, G, Gallay, PA. Syndecans serve as attachment receptors for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on macrophages. J Virol 75, :9187-9200. doi: 9110.1128/JVI.9175.9119.9187-9200.2001. (2001).

87 Chhabra, M., Shanthamurthy, CD, Kumar ,NV, Mardhekar, S, Vishweshwara, SS, Wimmer, N, Modhiran, N, Watterson, D, Amarilla, AA, Cha, JS, Beckett, JR, De Voss, JJ, Kayal, Y, Vlodavsky, I, Dorsett ,LR, Smith, RAA, Gandhi, NS, Kikkeri, R, Ferro, V. Amphiphilic Heparinoids as Potent Antiviral Agents against SARS-CoV-2. J Med Chem 67, 11885-11916. doi: 11810.11021/acs.jmedche m.11884c00487. (2024).

88 De Clercq, E. Potential drugs for the treatment of AIDS. J Antimicrob Chemother 23 Suppl A, 35-46. doi: 10.1093/jac/1023.suppl_a.1035 (1989).

89 Vert, M. The non-specific antiviral activity of polysulfates to fight SARS-CoV-2, its mutants and viruses with cationic spikes. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 32, 1466-1471. doi: 1410.1080/09205063.0920 2021.01925391. (2021).

90 Pavan, M., Fanti ,CD, Lucia, AD, Canato, E, Acquasaliente, L, Sonvico, F, Delgado, J, Hicks. A, Torrelles, JB, Kulkarni ,V, Dwivedi ,V, Zanellato, AM, Galesso, D, Pasut, G, Buttini, F, Martinez-Sobrido, L, Guarise, C. Aerosolized sulfated hyaluronan derivatives prolong the survival of K18 ACE2 mice infected with a lethal dose of SARS-CoV-2. Eur J Pharm Sci 187, 106489. doi: 106410. 101016/j.ejps.102023.106489. (2023).

91 Baba, M., Nakajima, M, Schols, D, Pauwels, R, Balzarini, J, De Clercq, E. . Pentosan polysulfate, a sulfated oligosaccharide, is a potent and selective anti-HIV agent in vitro. Antiviral Res 9, 335-343. doi: 310.1016/0166-3542(1088)90035-90036. (1988).

92 Rusnati, M., Urbinati, C, Caputo, A, Possati, L, Lortat-Jacob, H, Giacca, M, Ribatti, D, Presta, M. Pentosan polysulfate as an inhibitor of extracellular HIV-1 Tat. J Biol Chem 276, 22420-22425 (2001).

93 Biesert, L., Suhartono, H, Winkler, I, Meichsner, C, Helsberg, M, Hewlett, G, Klimetzek, V, Mölling, K, Schlumberger, HD, Schrinner, E, et al. Inhibition of HIV and virus replication by polysulphated polyxylan: HOE/BAY 946, a new antiviral compound. AIDS 2, 449-457. doi: 410.109 7/00002030-198812000-198800007. (1988).

94 Biesert , L., Adamski, M, Zimmer, G, Suhartono, H, Fuchs, J, Unkelbach, U, Mehlhorn, RJ, Hideg, K, Milbradt, R, Rübsamen-Waigmann, H. . Anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) drug HOE/BAY946 increases membrane hydrophobicity of human lymphocytes and specifically suppresses HIV-protein synthesis. Med Microbiol Immunol 179, 307-321. doi: 310.1007/BF00189609. (1990).

95 von Briesen, H., Meichsner ,C, Andreesen, R, Esser, R, Schrinner, E, Rübsamen-Waigmann, H. . The polysulphated polyxylan Hoe/Bay-946 inhibits HIV replication on human monocytes/macrophage s. Res Virol 141, 251-257. doi: 210.1016/0923-2516(1090)90029-i. (1990).

96 Peters, M., Witvrouw, M, De Clercq, E, Ruf, B. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous pentosan polysulphate (HOE/BAY 946) in HIV-positive patients. AIDS 5, 1534-1535. doi: 1510.1097/000 02030-199112000-199100021. (1991).

97 Pearce-Pratt, R., Phillips, DM. . Sulfated polysaccharides inhibit lymphocyte-to-epithelial transmission of human immunodeficiency virus-1. Biol Reprod 54, 173-182. doi: 110.1095/biolreprod 1054.1091.1173. (1996).

98 Witvrouw, M., Desmyter, J, De Clercq, E. . Antiviral portrait series: 4. Polysulfates as inhibitors of HIV and other enveloped viruses. . Antiviral Chemistry & ChemotherapY 5, 345-359 (1994).

99 Jurkiewicz E, P. P., Jentsch KD, Hartmann H, Hunsmann G. In vitro anti-HIV-1 activity of chondroitin polysulphate. AIDS. 3, 423-427. doi: 410.1097/00002030-198907000-198900003. (1989).

100 Vanderlinden, E., Boonen, A, Noppen, S, Schoofs, G, Imbrechts, M, Geukens, N, Snoeck, R, Stevaert ,A, Naesens, L, Andrei ,G, Schols, D. PRO-2000 exhibits SARS-CoV-2 antiviral activity by interfering with spike-heparin binding. Antiviral Res 217, 105700. doi: 105710.101016/j.antiviral.10 2023.105700. (2023).

101 Huskens, D., Profy, AT, Vermeire, K, Schols, D. PRO 2000, a broadly active anti-HIV sulfonated compound, inhibits viral entry by multiple mechanisms. Retrovirology 7 Suppl 1, P17. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-1187-S1181-P1117 (2010).

102 Nakamura, T., Satoh, K, Fukuda, T, Kinoshita, I, Nishiura, Y, Nagasato, K, Yamauchi, A, Kataoka, Y, Nakamura, T, Sasaki, H, Kumagai, K, Niwa, M, Noguchi, M, Nakamura, H, Nishida, N, Kawakami, A. Pentosan polysulfate treatment ameliorates motor function with increased serum soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in HTLV-1-associated neurologic disease. J Neurovirol 20, 269-277. doi: 210.1007/s13365-13014-10244-13368. (2014).

103 Callaway, E. Heavily mutated Omicron variant puts scientists on alert. Nature 600, 21 (2021).

104 WHO. Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern. (2021).

105 Smith, M., Melrose, J. . Pentosan Polysulfate Affords Pleotropic Protection to Multiple Cells and Tissues. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 16, 437 (2023).

106 GISAID. https://www.gisaid.org/hcov19-variants/. (2021).

107 Basheer, A., Zahoor, I, Yaqub, T. . Genomic architecture and evolutionary relationship of BA.2.75: A Centaurus subvariant of Omicron SARS-CoV-2. PLoS One 18, e0281159. doi: 0281110.0 281371/journal.pone.0281159. (2023).

108 Caputo, E., Mandrich, L. SARS-CoV-2: Searching for the Missing Variants. Viruses 14, 2364. doi: 2310.3390/v14112364. (2022).

109 Zappa, M., Verdecchia, P, Angeli, F. Knowing the new Omicron BA.2.75 variant (‘Centaurus’): A simulation study. Eur J Intern Med 105, 107-108. doi: 110.1016/j.ejim.2022.1008.1009. (2022).

110 Sabbatucci, M., Vitiello, A, Clemente, S, Zovi, A, Boccellino, M, Ferrara, F, Cimmino, C, Langella, R, Ponzo, A, Stefanelli, P, Rezza, G. . Omicron variant evolution on vaccines and monoclonal antibodies. Inflammopharmacology 31, 1779-1788 . doi: 1710.1007/s10787-10023-01253-10786 (2023).

111 Fernandes, Q., Inchakalody, VP, Merhi, M, Mestiri, S, Taib, N, Moustafa, Abo El-Ella, D, Bedhiafi, T, Raza, A, Al-Zaidan, L, Mohsen, MO, Yousuf Al-Nesf, MA, Hssain, AA, Yassine, HM, Bachmann, MF, Uddin, S, Dermime, S. Emerging COVID-19 variants and their impact on SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis, therapeutics and vaccines. Ann Med 54, 524-540 (2022).

112 Dechecchi, M., Tamanini, A, Bonizzato, A, Cabrini, G. Heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans are involved in adenovirus type 5 and 2-host cell interactions. Virology 268, 382-390 (2000).

113 Lerch, T., Chapman, MS. . Identification of the heparin binding site on adeno-associated virus serotype 3B (AAV-3B). . Virology 423, 6-13 (2012).

114 Qiu, J., Handa, A, Kirby, M, Brown, KE. . The interaction of heparin sulfate and adeno-associated virus 2. Virology 269, 137-147 (2000).

115 Murakami, S., Takenaka-Uema, A, Kobayashi,T, Kato, K, Shimojima, M, Palmarini, M, Horimoto, T. Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan Is an Important Attachment Factor for Cell Entry of Akabane and Schmallenberg Viruses. J Virol 91, pii: e00503-00517 (2017).

116 McAllister , N., Liu, Y, Silva, LM, Lentscher, AJ, Chai, W, Wu, N, Griswold, KA, Raghunathan, K, Vang, L, Alexander ,J, Warfield, KL, Diamond, MS, Feizi,T, Silva, LA, Dermody, TS. Chikungunya Virus Strains from Each Genetic Clade Bind Sulfated Glycosaminoglycans as Attachment Factors. J Virol 94, e01500-01520. (2020).

117 Merilahti, P., Karelehto, E, Susi, P. Role of Heparan Sulfate in Cellular Infection of Integrin-Binding Coxsackievirus A9 and Human Parechovirus 1 Isolates. . PLoS One 11, e0147168 (2016).

118 Pourianfar , H., Kirk, K, Grollo, L. Initial evidence on differences among Enterovirus 71, Coxsackievirus A16 and Coxsackievirus B4 in binding to cell surface heparan sulphate. Virusdisease 25, 277-284 (2014).

119 Zautner, A., Jahn, B, Hammerschmidt, E, Wutzler, P, Schmidtke, M. N- and 6-O-sulfated heparan sulfates mediate internalization of coxsackievirus B3 variant PD into CHO-K1 cells. J Virol 80, 6629-6636 (2006).

120 Artpradit, C., Robinson, LN, Gavrilov, BK, Rurak, TT, Ruchirawat, M, Sasisekharan, R. Recognition of heparan sulfate by clinical strains of dengue virus serotype 1 using recombinant subviral particles. Virus Res 176, 69-77 (2013).

121 Hilgard, P., Stockert, R. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans initiate dengue virus infection of hepatocytes. Hepatology 32, 1069-1077 (2000).

122 Saksono, B., Dewi, BE, Nainggolan, L, Suda, Y. A Highly Sensitive Diagnostic System for Detecting Dengue Viruses Using the Interaction between a Sulfated Sugar Chain and a Virion. PLoS One 10, e0123981 (2015).

123 Wu, S., Wu, Z, Wu, Y, Wang, T, Wang, M, Jia, R, Zhu, D, Liu, M, Zhao, X, Yang, Q, Wu, Y, Zhang, S, Liu, Y, Zhang, L, Yu, Y, Pan, L, Chen, S, Cheng, A. . Heparin sulfate is the attachment factor of duck Tembus virus on both BHK21 and DEF cells. Virol J 16, 134 (2019).

124 Tamhankar, M., Gerhardt, DM, Bennett, RS, Murphy, N, Jahrling, PB, Patterson, JL. Heparan sulfate is an important mediator of Ebola virus infection in polarized epithelial cells. Virol J 15, 135 (2018).

125 Israelsson, S., Gullberg, M, Jonsson, N, Roivainen, M, Edman, K, Lindberg, AM. Studies of Echovirus 5 interactions with the cell surface: heparan sulfate mediates attachment to the host cell. Virus Res 151, 170-176 (2010).

126 Tan, C., Poh, CL, Sam, IC, Chan, YF. Enterovirus 71 uses cell surface heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan as an attachment receptor. . J Virol 87, 611-620 (2013).

127 Tan, C., Sam, IC, Lee, VS, Wong, HV, Chan, YF. VP1 residues around the five-fold axis of enterovirus A71 mediate heparan sulfate interaction. Virology 501, 79-87 (2017).

128 Salvador, B., Sexton, NR, Carrion, R Jr, Nunneley, J, Patterson, JL, Steffen, I, Lu, K, Muench, MO, Lembo, D, Simmons, G. . Filoviruses utilize glycosaminoglycans for their attachment to target cells. J Virol 87, 3295-3304 (2013).

129 Mathieu, C., Dhondt, KP, Châlons, M, Mély, S, Raoul, H, Negre, D, Cosset, FL, Gerlier, D, Vivès, RR, Horvat, B. Heparan sulfate-dependent enhancement of henipavirus infection. mBio 6, e02427 (2015).

130 Schulze, A., Gripon, P, Urban, S. . Hepatitis B virus infection initiates with a large surface protein-dependent binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Hepatology 16, 1759-1766 (2007).

131 Lamas Longarela, O., Schmidt, TT, Schöneweis, K, Romeo, R, Wedemeyer, H, Urban, S, Schulze, A. P. Proteoglycans act as cellular hepatitis delta virus attachment receptors. . PLoS One 8, e58340 (2013).

132 Olenina, L., Kuzmina, TI, Sobolev, BN, Kuraeva, TE, Kolesanova, EF, Archakov, AI. . Identification of glycosaminoglycan-binding sites within hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E2. . J Viral Hepat 12, 584-593 (2005).

133 Xu, Y., Martinez, P, Séron, K, Luo, G, Allain, F, Dubuisson, J, Belouzard, S. Characterization of hepatitis C virus interaction with heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Virol 89, 3846-3858 (2015).

134 Akula, S., Pramod, NP, Wang, FZ, Chandran, B. Human herpesvirus 8 envelope-associated glycoprotein B interacts with heparan sulfate-like moieties. Virology 284, 235-249 (2001).

135 Feyzi, E., Trybala, E, Bergström, T, Lindahl, U, Spillmann, D. . Structural requirement of heparan sulfate for interaction with herpes simplex virus type 1 virions and isolated glycoprotein C. J Biol Chem 372, 24850-24857 (1997).

136 Thammawat, S., Sadlon, TA, Hallsworth, PG, Gordon, DL. . Role of cellular glycosaminoglycans and charged regions of viral G protein in human metapneumovirus infection. J Virol 82, 11767-11774 (2008).

137 Karasneh, G., Ali,M, Shukla, D. . An important role for syndecan-1 in herpes simplex virus type-1 induced cell-to-cell fusion and virus spread. PLoS One 6, e25252 (2011).

138 Terry-Allison, T., Montgomery, RI, Warner, MS, Geraghty, RJ, Spear, PG. Contributions of gD receptors and glycosaminoglycan sulfation to cell fusion mediated by herpes simplex virus 1. Virus Res 74, 39-45 (2001).

139 Connell, B. a. L.-J., H. Human immunodeficiency virus and heparan sulfate: from attachment to entry inhibition. Frontiers in Immunology 4, 385 (2013).

140 Guibinga, G., Miyanohara, A, Esko, JD, Friedmann, T. Cell surface heparan sulfate is a receptor for attachment of envelope protein-free retrovirus-like particles and VSV-G pseudotyped MLV-derived retrovirus vectors to target cells. Mol Ther 5, 538-546 (2002).

141 Trkola, A., Gordon, C, Matthews, J, Maxwell, E, Ketas, T, Czaplewski ,L, Proudfoot, AE, Moore, JP. The CC-chemokine RANTES increases the attachment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to target cells via glycosaminoglycans and also activates a signal transduction pathway that enhances viral infectivity. J Virol 73, 6370-6379 (1999).

142 Nasimuzzaman, M., Persons, DA. Cell Membrane-associated heparan sulfate is a receptor for prototype foamy virus in human, monkey, and rodent cells. Mol Ther. 2012 Jun;20(6):1158-66. Cell Membrane-associated heparan sulfate is a receptor for prototype foamy virus in human, monkey, and rodent cells. Mol Ther 20, 1158-1166 (2012).

143 Plochmann, K., Horn, A, Gschmack, E, Armbruster, N, Krieg, J, Wiktorowicz, T, Weber, C, Stirnnagel, K, Lindemann, D, Rethwilm, A, Scheller, C. Heparan sulfate is an attachment factor for foamy virus entry. J Virol 86, 10028-10035 (2012).

144 Bousarghin, L., Hubert, P, Franzen, E, Jacobs, N, Boniver, J, Delvenne, P. Human papillomavirus 16 virus-like particles use heparan sulfates to bind dendritic cells and colocalize with langerin in Langerhans cells. J Gen Virol 86, 1297-1305 (2005).

145 Feldman, S., Audet, S, Beeler, JA. . The fusion glycoprotein of human respiratory syncytial virus facilitates virus attachment and infectivity via an interaction with cellular heparan sulfate. J Virol 74, 6442-6447 (2000).

146 Chang, A., Masante, C, Buchholz, UJ, Dutch, RE. Human metapneumovirus (HMPV) binding and infection are mediated by interactions between the HMPV fusion protein and heparan sulfate. J Virol 86, 3230-3243 (2012).

147 Su, C., Liao, CL, Lee, YL, Lin, YL. Highly sulfated forms of heparin sulfate are involved in japanese encephalitis virus infection. Virology 286, 206-215 (2001).

148 Chowalter, R., Pastrana, DV, Buck, CB. Glycosaminoglycans and sialylated glycans sequentially facilitate Merkel cell polyomavirus infectious entry. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002161 (2011).

149 Kureishy, N., Faruque, D, Porter, CD. Primary attachment of murine leukaemia virus vector mediated by particle-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan. Biochem J 400, 421-430 (2006).

150 Gillet , L., Adler, H, Stevenson ,PG. Glycosaminoglycan interactions in murine gammaherpesvirus-68 infection. PLoS One 2, e347 (2007).

151 Huan, C., Wang, Y, Ni, B, Wang, R, Huang, L, Ren, XF, Tong, GZ, Ding, C, Fan, HJ, Mao, X. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus uses cell-surface heparan sulfate as an attachment factor. . Arch Virol 160, 1621-1628 (2015).

152 Trybala, E., Bergström, T, Spillmann, D, Svennerholm, B, Olofsson, S, Flynn, SJ, Ryan, P. Mode of interaction between pseudorabies virus and heparan sulfate/ heparin. Virology 218, 35-42 (1996).

153 Sasaki, M., Anindita, PD, Ito, N, Sugiyama, M, Carr, M, Fukuhara, H, Ose, T, Maenaka, K, Takada, A, Hall, WW, Orba, Y, Sawa, H. The Role of Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans as an Attachment Factor for Rabies Virus Entry and Infection. J Infect Dis 217, 1740-1749 (2018).

154 Hallak, L., Spillmann, D, Collins, PL, Peeples, ME. Glycosaminoglycan sulfation requirements for respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Virol 74, 10508-10513 (2000).

155 Shields, B., Mills, J, Ghildyal, R, Gooley, P, Meanger, J. Multiple heparin binding domains of respiratory syncytial virus G mediate binding to mammalian cells. Arch Virol 148, 1987-2003 (2003).

156 Ennemoser, M., Rieger, J, Muttenthaler, E, Gerlza, T, Zatloukal, K, Kungl, AJ. Enoxaparin and pentosan polysulfate bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and human ACE2 receptor, inhibiting Vero cell infection. Biomedicines 10, 49 (2022).

157 Escribano-Romero, E., Jimenez-Clavero, MA, Gomes, P, García-Ranea, JA, Ley, V. Heparan sulphate mediates swine vesicular disease virus attachment to the host cell. J Gen Virol 85, 653-663 (2004).

158 Byrnes, A., Griffin, DE. Binding of Sindbis virus to cell surface heparan sulfate. J Virol 72, 7349-7356 (1998).

159 Hulst, M., van Gennip, HG, Moormann, RJ. . Passage of classical swine fever virus in cultured swine kidney cells selects virus variants that bind to heparan sulfate due to a single amino acid change in envelope protein E(rns). J Virol 74, 9553-9561 (2000).

160 Luteijn, R., van Diemen, F, Blomen, VA, Boer, IGJ, Manikam Sadasivam, S, van Kuppevelt, TH, Drexler, I, Brummelkamp, TR, Lebbink, RJ, Wiertz, EJ. . A Genome-Wide Haploid Genetic Screen Identifies Heparan Sulfate-Associated Genes and the Macropinocytosis Modulator TMED10 as Factors Supporting Vaccinia Virus Infection. J Virol 93, e02160-02118 (2019).

161 Tan, C., Sam, IC, Chong, WL, Lee, VS, Chan, YF. Polysulfonate suramin inhibits Zika virus infection. Antiviral Res 143, 186-194 (2017).

162 García-Villalón, D., Gil-Fernández, C. . Antiviral activity of sulfated polysaccharides against African swine fever virus. Antiviral Res 15, 139-148 (1991).

163 Baba, M., Snoeck, R, Pauwels, R, de Clercq, E. Sulfated polysaccharides are potent and selective inhibitors of various enveloped viruses, including herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, vesicular stomatitis virus, and human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 32, 1742-1745 (1988).

164 Baba, M., Nakajima, M, Schols, D, Pauwels, R, Balzarini, J, De Clercq, E. . Pentosan polysulfate, a sulfated oligosaccharide, is a potent and selective anti-HIV agent in vitro. Antiviral Res 9, 335-343 (1988).

165 Ma, G., Yasunaga, JI, Ohshima, K, Matsumoto, T, Matsuoka, M. Pentosan Polysulfate Demonstrates Anti-human T-Cell Leukemia Virus Type 1 Activities In Vitro and In Vivo. J Virol 93, e00413-00419 (2019).

166 Herrero, L., Foo, SS, Sheng, KC, Chen, W, Forwood, MR, Bucala, R, Mahalingam, S. Pentosan Polysulfate: a Novel Glycosaminoglycan-Like Molecule for Effective Treatment of Alphavirus -Induced Cartilage Destruction and Inflammatory Disease. J Virol 89, 8063-8076 (2015).

167 Krishnan, R., Duiker, M, Rudd, PA, Skerrett, D, Pollard, JGD, Siddel, C, Rifat, R, Ng, JHK, Georgius, P, Hererro, LJ, Griffin, P. Pentosan polysulfate sodium for Ross River virus-induced arthralgia: a phase 2a, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22, 271 (2021).

168 Tavares-Júnior, J., de Souza, ACC, Borges, JWP, Oliveira, DN, Siqueira-Neto, JI, Sobreira-Neto, MA, Braga-Neto, P. COVID-19 associated cognitive impairment: A systematic review. . Cortex 152, 77-97 (2022).

169 Kumagai, K., Shirabe, S, Miyata, N, Murata, M, Yamauchi, A, Kataoka, Y, Niwa, M. Sodium pentosan polysulfate resulted in cartilage improvement in knee osteoarthritis–an open clinical trial. BMC Clin Pharmacol 10, 7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-1110-1187. (2010).

170 Eita, M., Ashour, RH, El-Khawaga, OY. . Pentosan polysulfate exerts anti-inflammatory effect and halts albuminuria progression in diabetic nephropathy: Role of combined losartan. . Fundam Clin Pharmacol 36, 801-810. doi: 810.1111/ fcp.12781 (2022).

171 Rudd, P., Lim, EXY, Stapledon, CJM, Krishnan, R, Herrero, LJ. Pentosan polysulfate sodium prevents functional decline in chikungunya infected mice by modulating growth factor signalling and lymphocyte activation. PLoS ONE 16, e0255125 (2021).

172 Krishnan, R., Stapledon, CJM, Mostafavi, H, Freitas, JR, Liu, X, Mahalingam, S, Zaid, A. Anti-inflammatory actions of Pentosan polysulfate sodium in a mouse model of influenza virus A/PR8/34-induced pulmonary inflammation. Front Immunol 14, 1030879. doi: 1030810.103338 9/fimmu.1032023.1030879 (2023).

173 Bertini, S., Alekseeva, A, Elli, S, Pagani, I, Zanzoni, S, Eisele, G, Krishnan, R, Maag, KP, Reiter, C, Lenhart, D, Gruber, R, Yates, EA, Vicenzi, E, Naggi, A, Bisio, A, Guerrin,i M. Pentosan Polysulfate Inhibits Attachment and Infection by SARS-CoV-2 In Vitro: Insights into Structural Requirements for Binding. . Thromb Haemost 122, 984-997. doi: 910.1055/a-1807-0168 (2022).

174 Wool, G., Miller, JL. . The Impact of COVID-19 Disease on Platelets and Coagulation. Pathobiology 88, 15-27, doi:doi: 10.1159/000512007. (2021).

175 Iba, T., Levy, JH, Levi ,M, Thachil, J. Coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost 18, 2103-2109, doi:doi: 10.1111/jth.14975 (2020).

176 Grobler, C., Maphumulo, SC, Grobbelaar, LM, Bredenkamp, JC, Laubscher, GJ, Lourens, PJ, Steenkamp, J, Kell, DB, Pretorius, E. Covid-19: The Rollercoaster of Fibrin(Ogen), D-Dimer, Von Willebrand Factor, P-Selectin and Their Interactions with Endothelial Cells, Platelets and Erythrocytes. Int J Mol Sci 21, 5168, doi: doi: 10.3390/ijms21145168. (2020).

177 Vögtle, T., Sharma, S, Mori, J, Nagy, Z, Semeniak, D, Scandola, C, Geer, MJ, Smith, CW, Lane, J, Pollack, S, Lassila, R, Jouppila, A, Barr, AJ, Ogg, DJ, Howard, TD, McMiken, HJ, Warwicker, J, Geh C, Rowlinson, R, Abbott ,WM, Eckly, A, Schulze, H, Wright ,GJ, Mazharian, A, Fütterer, K, Rajesh, S, Douglas, MR, Senis, YA. Heparan sulfates are critical regulators of the inhibitory megakaryocyte-platelet receptor G6b-B. . Elife 8, e46840 (2019).

178 Koupenova, M., Corkrey, HA, Vitseva, O, Tanriverdi, K, Somasundaran, M, Liu, P, Soofi, S, Bhandari, R, Godwin, M, Parsi, KM, Cousineau, A, Maehr, R, Wang, JP, Cameron, SJ, Rade, J, Finberg, RW, Freedman, JE. SARS-CoV-2 Initiates Programmed Cell Death in Platelets. Circ Res 129, 631-646 (2021).