Managing Chronic Fatigue: Insights for Medical Professionals

Managing chronic fatigue conditions with overlapping symptoms, and the health policies and social services supporting those affected

Warren Tate1*, Katie Peppercorn2, Nicholas Bowden3,4, Fiona Charlton5,6

- Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine-Dunedin, University of Otago, Dunedin, NZ

- Department of Biochemistry, School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Otago, Dunedin, NZ

- Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Medicine – Dunedin, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

- Faculty of Health, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand

- Aotearoa New Zealand Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Society Inc.

- Complex Chronic Illness Support Inc.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 November 2025

CITATION: Tate, W., Peppercorn, K., et al., 2025. Managing chronic fatigue conditions with overlapping symptoms, and the health policies and social services supporting those affected. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(11). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i11.7104

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i11.7104

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Complex chronic conditions present a formidable challenge to clinicians to diagnose and manage for their patients, and the diseases are still relatively poorly understood. The chronic fatigue conditions, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic fatigue syndrome, Long COVID, Fibromyalgia, Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and Multiple sclerosis, share many overlapping symptoms that reflect similar physiological responses, sometimes leading to misdiagnosis, yet the conditions are distinct and are being managed as separate diseases. The characteristics of what is known about each condition are described here, and as well for two comorbidities, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome and Mast cell Activation Syndrome intimately linked to the physiological dysfunctions of the chronic conditions. The pathophysiological changes in immunological function, neurological regulation, metabolism and energy production, and the microbiome affecting the gut-immune brain axis are discussed and compared for each condition. The difficulties encountered for diagnosis, and the current lack of effective treatment options are highlighted. Evidence is presented that affected patients have pressing needs, and that there are currently barriers that prevent access to more effective health support, result in patients being isolated lifelong from employment, and that block access to the essential social services. Effective public health policy is needed to ensure these inadequacies in public health support are overcome, and financial support is provided to ensure all patients have an enhanced quality of life. There may be significant benefit for affected patients if research and collective knowledge of these conditions and comorbidities are shared and more integrated, to promote better understanding for their management, provide a wider range of common treatment options, and stimulate more coordinated health policies for the management of patient support. Multiple sclerosis is far better served than the other conditions and could provide the model for how chronic conditions could be managed better.

Keywords

- Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

- Long COVID

- Fibromyalgia

- Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome

- Mast Cell Activation Syndrome

1. Introduction

This review discusses common features in each of the complex chronic conditions, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), Long COVID (LC), Fibromyalgia (FM), Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), and Multiple Sclerosis (MS), together with two comorbidity syndromes that are closely linked with them, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS).

1.1 DEFINITIONS AND DESCRIPTIONS OF THE CHRONIC CONDITIONS

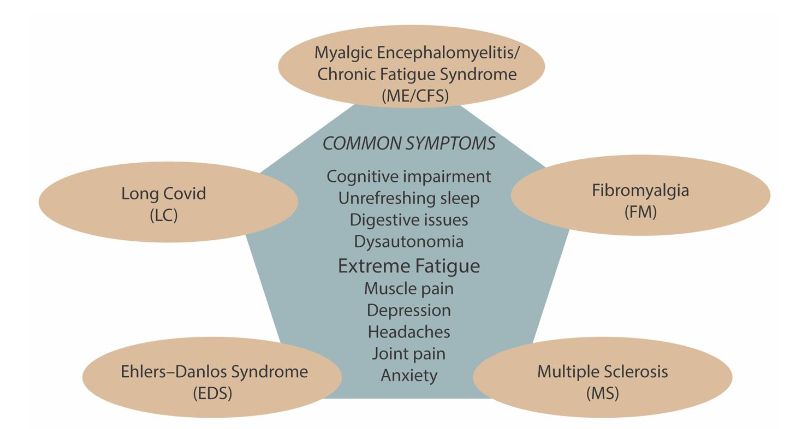

The characteristics of each the chronic conditions are discussed below, and the overlapping symptoms are shown in Figure 1.

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue syndrome Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is the name given to a post-viral/stressor syndrome that develops in the susceptible 5-10% of the population after a triggering event, typically a virus infection (80%) but also other major stressor events (20%). These alternative triggers include exposure to other infectious agents or toxic agricultural chemicals, stressors like major surgery, or simply a challenging life event or an underlying health condition. The name ME/CFS is derived from conditions that arose following two separate geographically isolated infectious disease outbreaks, ME (London 1955) and CFS (Nevada 1984). The combined name became universally accepted around 2016 as they have the same clinical phenotype. With no currently effective treatments that can reverse ME/CFS, the condition is lifelong for most affected. Twenty five percent remain severely affected in an acute phase, while the majority progress to a more chronic phase of variable severity that still significantly affects their lives every day. This means new cases add continually to the accumulating patient numbers, and increase the disease burden on families, communities, and economies. ME/CFS is now understood to be a complex, multi-system condition involving dysfunction in the immune, endocrine, autonomic, and neurological systems, with over 200 documented symptoms.

Long COVID

Long Covid encompasses an ME/CFS-like condition that arose from the global COVID pandemic as a large subgroup (~50%) of those affected with ongoing disease from the SARS-CoV-2 infection. This sudden appearance of large numbers of a post-viral condition with the adopted name LC was unprecedented. The infectious disease outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 was global with vast numbers infected from all ethnic groups and cultures. Long COVID is unique in that all cases are triggered by the single virus as compared with the many triggers for ME/CFS and, while the pathophysiology may have unique features because of the character of the infecting virus, 95% of the > 200 symptoms reported overlap with those experienced by ME/CFS patients. Core symptoms for both conditions include fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, post-exertional malaise (PEM), pain, and unrefreshing sleep. Other important symptoms result from dysfunction of regulatory functions of the autonomic nervous system (dysautonomia) – such as of heart rate, blood pressure, blood sugar, temperature, and the gastrointestinal system. A very recent self-reporting survey of 4000 patients with ME/CFS and LC found the frequencies of many overlapping symptoms were similar. With overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms documented, researchers are starting to explore how closely related LC is to ME/CFS at the detailed molecular level. LC patients by contrast to ME/CFS patients obtained a diagnosis during the pandemic period much earlier than ME/CFS as it was clearly linked and ongoing from their COVID infections. There are reports of recovery from LC within the first two years, but estimates are widely diverse. These recoveries indicate that early diagnosis may be critical for chances of recovery and preventing the illness becoming lifelong. Even individuals who recover from LC however, have been found to be at increased risk for cardiovascular, neurological, and metabolic disorders. The long-term future consequences are profound for health systems with LC numbers that may be as high as 400 million, adding to the burden of ME/CFS (~20-30 million estimated worldwide). With the SARS-CoV-2 virus now having become an endemic virus, generating new cases every day like ME/CFS, the collective societal burden is growing steadily by the day.

Fibromyalgia (FM)

Fibromyalgia is classified as a chronic disorder of pain regulation characterised by widespread body pain. The increase sensitivity to pain is likely the result of the central nervous system not processing pain signals normally, and muscle stiffness. Nevertheless, FM has many other symptoms that overlap with ME/CFS such as fatigue, sleep problems, and cognitive difficulties with memory loss and brain fog, as well as digestive problems. The cause of the condition is not clear, but it is often triggered like ME/CFS by the same infectious agents, for example Epstein Barr virus, or major stress events, as well as by injuries, but like ME/CFS can also develop without a clearly identified cause. It has been suggested that susceptibility might have a genetic origin with first-degree relatives having a >10 times higher incidence of developing FM than healthy controls without such a connection. A genome-wide study involving FM patients with chronic widespread pain has identified an association with the RNF123 gene and a possible association with the ATP2C1 gene, both of which are involved in calcium regulation. Other possible associated genes have also been suggested. It should be noted, very recent reports for ME/CFS and LC reveal there are also genetic components that convey susceptibility to developing these conditions when the immune system is challenged by a major triggering stress like a viral infection.

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) is primarily known as a condition affecting collagen formation and function affecting organ systems, with clinical symptoms of skin hyper elasticity, hypermobility of joints and fragility of blood vessels. It has been classified into multiple subtypes, some of which are very rare, and they have overlapping clinical presentation. This condition also manifests many of the symptoms, severe fatigue, chronic pain, and those arising from dysautonomia that are found in ME/CFS, LC, and FM, so despite being a quite distinct disease of hypermobility it can easily be misdiagnosed. Joint hypermobility has been observed in patients with the diagnosis of ME/CFS. From an analysis of an EDS group of patients those with hypermobility (15.5% of the 126 patients in the study) had a more distinctive clinical phenotype. This current ambiguity of many of the patients, however, makes management of the condition more complex. Unlike ME/CFS, LC, and FM that can develop as a result from a triggering event like a viral infection, the EDS subtypes are linked directly to a number of different genetic causes, with the most common having autosomal dominant inheritance, and other types of autosomal recessive inheritance. Classical EDS (cEDS) has mutations in COL5A1 or COL5A2, and Vascular EDS (vEDS) in COL3A1. Other EDS types are caused by different gene mutations, such as PLOD1 or FKB14 or ADAMTS2. So, EDS susceptibility is manifested directly by having a dysfunctional gene. This contrasts with the recent information has shown also for ME/CFS, LC and FM that there is also a susceptible group of the population, who have predisposing complex genetic variations but they are silent until a second trigger/stressor event is experienced. That may be a viral infection like the COVID SARS-CoV-2 virus for LC, or endemic viruses and other major stressors for ME/CFS.

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is divided into what are named different types (as distinct from stages). Radiologically isolated syndrome refers to findings on MRIs of the brain and spinal cord that look like MS in someone without classic symptoms of MS. Clinically isolated syndrome refers to the first episode of a condition that affects the myelin. After further testing, clinically isolated syndrome may be diagnosed as MS or a different condition. Most people with multiple sclerosis have the relapsing-remitting type with episodes of symptoms or relapses that develop over days or weeks and then usually improve partially or completely. These relapses can be followed by disease remission that can last months or even years. Up to half of those with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis eventually develop a steady progression of symptoms without periods of remission that can occur many years after disease onset. This is known as secondary-progressive MS. The worsening of symptoms usually includes trouble with mobility and walking, but the rate of disease progression is highly variable. Some people experience a gradual onset of MS and steady progression of signs and symptoms without any relapses. This type of MS is known as primary-progressive MS. While superficially MS looks to be outside the overlapping nature of the other chronic conditions being a progressive disease unlike ME/CFS and LC, the symptoms include debilitating fatigue that is more intense after exercise (post exertional malaise), cognitive difficulties (brain fog), symptoms of dysautonomia, poor balance, sensory disturbances like pins and needles, and pain. MS like ME/CFS is also invoked to be triggered by infections, or stress although one study does not support a major role for stress in the initial development of MS. A number of studies suggest however major ongoing stressor events can precipitate relapses just as in ME/CFS. MS is regarded an autoimmune disease affecting the central nervous system, but evidence has been presented that both supports and challenges this autoimmune hypothesis. ME/CFS also shows some enhanced autoimmunity, but it is not regarded as an autoimmune disease. Overlapping symptoms between EDS and MS also include fatigue, headaches with migraines, autonomic dysfunction, chronic pain, and neuropathy. While EDS is a connective tissue disorder and MS is a demyelinating autoimmune disease their shared symptoms can also lead to diagnostic confusion, and there is evidence suggesting EDS patients have a 10-fold increased susceptibility of developing MS.

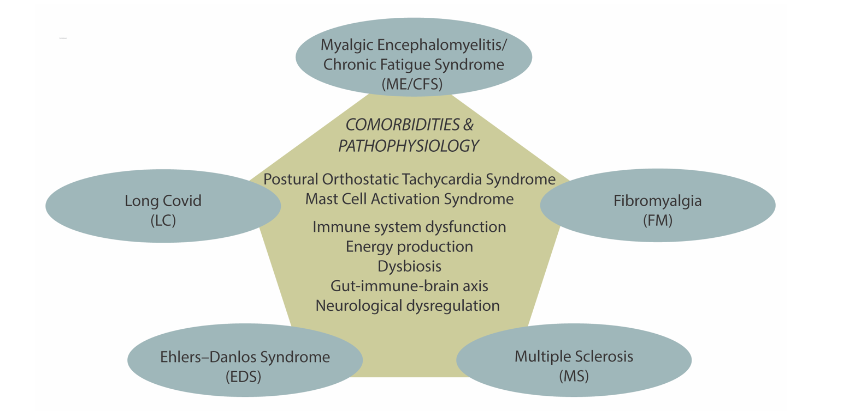

2. Shared co-morbidities among the chronic conditions.

Two of the co-morbid conditions that commonly appear with these chronic conditions warrant special attention here: Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS).

POSTURAL ORTHOSTATIC TACHYCARDIA SYNDROME

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) is a common orthostatic intolerance condition, frequently co-occurring with ME/CFS and LC. It affects the autonomic nervous system’s ability to regulate heart rate and blood pressure when the affected person is standing up. While POTS can cause dizziness, weakness, and fatigue, it can significantly worsen these symptoms in ME/CFS patients, often leading to greater disability and more intense fatigue and exercise intolerance than POTS alone. Estimates of the prevalence of POTS in ME/CFS patients in different studies has varied widely (11-75%), the most recent study of a large cohort showing 25%. Such variation makes definitive interpretation of how significant POTS is to ME/CFS pathophysiology. It is estimated ~20% of FM patients also have POTS as a comorbidity, and in EDS patients an incidence of POTS has been estimated to be ~30%. There is also an increased incidence of POTS in MS patients that at ~20%, is at least twice that of the general population. POTS is still a poorly understood clinical entity, and its complexity and wide range of clinical presentations has led to it being commonly mistaken for malingering, depression and anxiety disorders, as well as having the diagnosis of the chronic illnesses discussed here. Since many of those diagnosed with POTS also have many other symptoms overlapping with the chronic diseases, such as cognitive difficulties, temperature sensitivity and gut problems there are significant challenges both for diagnosis and treatment. Management of POTS often involves a combination of medications, and self-care strategies, aimed to stabilize the autonomic nervous system and improve quality of life. All three of POTS, EDS and FM also frequently co-occur, sharing through autonomic dysfunction chronic pain from central sensitisation, fatigue, and common hypermobility traits. Although POTS is characterised by symptoms triggered by standing upright, FM primarily involves widespread musculoskeletal pain and fatigue, and EDS a connective tissue disorder that can result in joint hypermobility, the high overlap implies shared underlying neurological mechanisms.

MAST CELL ACTIVATION SYNDROME

Mast cells are a class of white blood cells that protect the body by promoting inflammation. Mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) occurs when mast cells release excessive amounts of multiple mediators like histamine. Patients are affected with multiple symptoms affecting the brain and other organs from the diversity of mediators released and often do not get a diagnosis until many years after onset. A consensus for diagnosis was published in 2021. One component of a diagnostic test is serum Tryptase, an enzyme secreted by mast cells at the peak of an activation episode. MCAS is associated with many conditions as a comorbidity including those discussed here and with POTS. The symptoms can be very similar to those of ME/CFS with symptoms occurring across all parts of the body. Understanding the relationship between MCAS and ME/CFS is still at an early stage.

3. Comparisons of pathophysiology of the chronic conditions

The shared pathophysiology are illustrated in Figure 2 and discussed below.

IMMUNOLOGICAL DYSFUNCTION

A core feature of ME/CFS and LC is chronic activation of the immune system after the initial triggering event, such as a viral infection or major stress event that results in altered immune cell function, chronic inflammation and potentially immune exhaustion. Immune damage has been documented in LC and T cell dysregulation and uncoordinated adaptive immune response identified. In FM by contrast autoantibodies have been detected against autonomic nervous system receptors in the serum of patients in titres that correlate with clinical symptoms. This implies an important autoimmune component to the condition. The immune system is so complex that understanding the commonalities among the conditions would benefit from comparative and longitudinal studies where the same features were being compared. Different studies with ME/CFS have often led to contrary findings that may result from the stage (time from onset) of the illness, the clinical case definition used for diagnosis, or some other aspect of the study protocol.

NEUROLOGICAL REGULATION

ME/CFS is classified by the World Health Organisation as a central nervous system disorder of the brain and spinal cord as a result of its core neurological symptoms of fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, pain, unrefreshing sleep, and post exertional malaise. As indicated above, it involves significant disturbance of the autonomic nervous system’s regulation of body functions like heart rate, blood pressure, digestion and temperature regulation that give rise to widespread disturbed physiology. A 2014 study supporting neuroinflammation as a significant component has awaited confirmation and that has very recently come with a study that shows that neuroinflammation is widespread in the brain. An involvement of autoantibodies has been proposed targeting adrenergic receptors that may be an abnormal enhancement of a normal physiological control. Long Covid has similar core neurological symptoms as ME/CFS, and there are many similarities between ME/CFS and LC in changes to the epigenetic DNA methylome, including at specific gene promoters and gene bodies most of which would dampen down expression of the same genes. More extensive and detailed imaging studies have been carried out now on LC showing with Fluorodeoxyglucose-Positron Emission Tomography (FDG -PET) imaging that hypometabolism in ~50% of patients in extensive parts of the brain, and neuroinflammation. The unique findings in studies of ME/CFS and LC patients to date are most likely complementary implying both have common distinct neurological features. Fibromyalgia also involves neurological dysregulation, with a primary feature of the central nervous system becoming hypersensitive to pain signals, leading to widespread pain, fatigue, and other symptoms. This dysfunction is associated with enhanced or depressed neurotransmitter levels, impaired pain regulation, and abnormalities in brain structures and connectivity. Pain has dominated the literature with FM, although it has the core neurological symptoms of ME/CFS as well. The term nociplastic pain syndrome has been used for this combination. These overlapping symptoms have been invoked to contribute to this overactivity of the central nervous system and elevation of pain-signalling transmitters like Substance P and glutamate. Anti-GPCR (anti- G protein-coupled receptor antibodies), autoantibodies directed against the autonomic nervous system receptors, have been detected in the serum of patients with FM, at levels that correlated with clinical symptoms so this could be the primary feature connected with pain and distinguishes FM from the other chronic conditions. Neurological regulation studies in EDS have not been extensive despite the overlapping neurological symptoms with ME/CFS. A recent study raised the possibility of “co-existence with a functional neurological disorder.” Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune and neurological disease that affects the central nervous system including the brain and spinal cord. Shared neurological symptoms with ME/CFS include fatigue, and cognitive dysfunctions, as well as autonomic nervous system dysfunctions involving temperature regulation, cardiovascular regulation and gastrointestinal functions and including POTS and neuroinflammation. Dominant and distinctive from the other chronic conditions, however, is the demyelination of the nerves that affect the central nervous system but is now known to spread to the peripheral nervous system as well.

METABOLISM AND ENERGY PRODUCTION

Both ME/CFS and LC share mechanistic deficits in mitochondrial energy production consistent with the pervasive fatigue and post-exertional malaise experienced by patients. This involves widespread dysregulation of the production of mitochondrial proteins in immune cells, and in mechanisms of mitochondrial energy production. As well, in vivo phosphorus 31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy in muscles of patients following exercise revealed lower mitochondrial metabolism and ATP synthesis rate, with increased intracellular acidosis consistent with glycolytic anaerobic metabolism. Metabolism is disrupted generally, and that extends to the brain where metabolic profiling has shown changes in both ME/CFS and LC. The conclusion from a plethora of studies is that energy production and overall metabolism is disrupted over a wide range of tissues in both ME/CFS and LC. Mitochondrial function is also impaired in FM with lower spare respiratory capacity and a lower bioenergetic health index (overall bioenergetic capacity) having been found that correlated with disease severity. Dysfunctional energy metabolism in brain was investigated with creatine metabolites by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and conclusions were that FM patients had lower energy levels. Although the number of studies is limited and not directly comparable with those on ME/CFS and LC studies they are suggestive of common mechanisms of dysfunction. There is growing evidence that similar metabolic disturbances occur in FM as in ME/CFS although evidence is not yet at the level to conclude the mechanisms are the same. Studies of EDS and mitochondrial function and metabolism are in their infancy as discussed in a recent review that proposes a mitochondrial dysfunction mechanism in hypermobile EDS might be a unifying mechanism of the pathophysiology. Metabolism has been invoked to be affected through gastrointestinal (GI) issues that lead to nutrient malabsorption and thereby nutrient deficiencies, but GI issues are also very common in ME/CFS patients and so the consequences may provide an overlapping feature of the pathophysiology of these conditions.

GUT-IMMUNE-BRAIN AXIS

Currently the gut-immune-brain axis is a highly active area of current research that has implications for all chronic diseases. Gut dysbiosis, a significant change in the microbiota is common in ME/CFS patients. It leads to significant problems in the gastrointestinal system that has consequences for both the immune system and the nervous system. The resulting increased permeability of the gut allows leakage of bacterial products into the blood stream thereby activating an immune inflammatory response that ultimately affects the brain. Early studies suggest this extends to LC. The role of the microbiota in FM is now also being recognised. A high proportion of EDS patients are reported to have GI complaints and so likely have a similar immune inflammatory and brain effect that negatively impacts their overall pathophysiology. As with the other chronic conditions it has been inferred the gut-immune-brain axis has a critical role in the pathophysiology of MS.

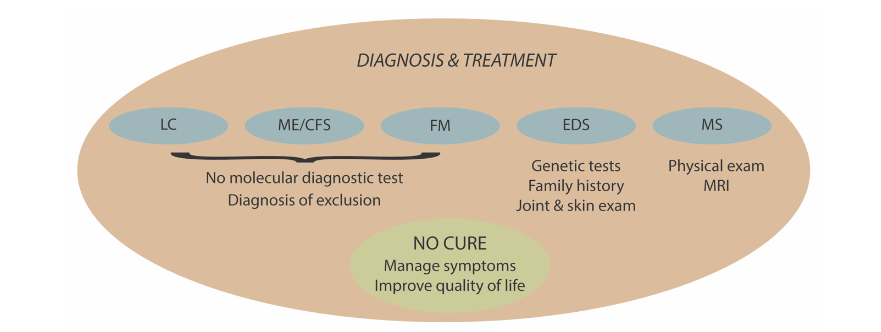

4. Diagnoses and treatments

The means of diagnosis and lack of effective treatment options for the chronic conditions are illustrated in Figure 3 and discussed below.

MYALGIC ENCEPHALOMYELITIS/CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME

ME/CFS can be given a preliminary diagnosis currently according to one or more of three preferred clinical case definitions if symptoms persist for six months in adults and three months in children and then it needs confirming following careful elimination of similar fatigue illnesses, a process that can take up to two years or more for many patients. There are no molecular diagnostic tests easily accessible and readily available to clinicians and patients outside of research laboratories. Over 150 treatments have been tried by patients to alleviate their debilitating symptoms, with the most effective giving at best a modest improvement to a modest proportion of the patients. No treatment modality has been found that will benefit most patients – generally the most promising treatments benefit some, have no effect on others, and cause a worsening of the condition in a third group.

LONG COVID

The ME/CFS-like subgroup of LC received their diagnosis if their condition persisted for 3 months after their SARS-CoV-2 infection. Knowing that the condition had arisen from the COVID infection has given patients an early suggestive diagnosis and guidelines to not try to launch back into a normal routine too quickly for a chance of an early recovery. This advantage has now been lost as the virus has become endemic, and testing and recording of cases are no longer taking place. They now will be in the same position as those suspected of having ME/CFS, and indeed some clinical experts are saying after two years the condition should be called ME/CFS. Despite the infusion of significant research money to identity effective treatments for LC, no effective universal treatment has yet emerged despite the intense efforts.

FIBROMYALGIA

Fibromyalgia is diagnosed based on symptoms with widespread pain the dominant symptom if it lasts three months. Other conditions with widespread pain as a core symptom must be eliminated for an accurate diagnosis. Currently, preferred treatments combine different health modalities including physical activity, antidepressant drugs, anti-seizure drugs and tricyclics, psychological therapies and other complementary medicine therapies like acupuncture and massage, all focussed on managing the severe chronic pain and trying to improve the quality of life for the patient.

EHLERS-DANLOS SYNDROME

A family history of the syndrome, and joint hypermobility and skin hyperextensibility may be sufficient for diagnosis of the hypermobile EDS type, but other subtypes that have a known specific genetic origin can be confirmed by a blood based genetic test. Treatments focus on physical therapies to strengthen muscles and stabilise joints with pain management through medications, and when required surgery for damaged joints and dislocations. As with the other chronic conditions there is no cure, and the aim is to give the patients a better quality of life.

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

As with the other chronic conditions there is no specific molecular diagnostic test for MS. The diagnosis is made from a combination of medical history, physical exam and MRI of the brain and spinal cord to show demyelination lesions. Examining antibodies in a cerebrospinal fluid sample can reveal MS linked changes. Evoked potential tests can measure how quickly information travels down nerve pathways, and optical coherence tomography can be used to detect optic neuritis associated with MS. Such tests are coupled with elimination of other conditions that might produce similar symptoms. In patients experiencing relapsing-remitting MS the diagnosis is easier than in people with unusual symptoms or progressive disease. There is no cure for MS, so treatments aim at accelerating recovery from relapses, reducing their frequency, and slowing the disease progression while managing symptoms if necessary. Steroids are used to reduce nerve inflammation during a relapse. Several medications not without side effects are available to reduce relapse rates.

5. Current barriers to health services, employment, and social services

HEALTH SERVICES

All the chronic conditions discussed here (ME/CFS, LC, FM, EDS, and MS) are associated with substantial health burdens, high healthcare utilisation, and have profound impacts on quality of life. ME/CFS and LC are among the most disabling conditions, with international studies reporting some of the lowest health-related quality-of-life scores across chronic illnesses, often lower than those seen in MS and cancer. Delayed diagnosis, sometimes by several years, and a lack of access to pacing education (limiting one’s activity) contribute to worsening symptom severity, greater functional decline, and higher long-term healthcare utilisation. EDS and FM patients also experience high healthcare use, driven by chronic pain, fatigue, and multisystem involvement, but face additional challenges from under-recognition and misdiagnosis, often delaying treatment and increasing complexity. Historical controversies, such as regarding ME/CFS as a psychological illness, have impeded biomedical research and policy action, a pattern once seen in MS before scientific investment transformed its care. Prevalence estimates indicate that ME/CFS affects more people than MS and the autoimmune condition, lupus erythematosus, combined, yet research and service provision remain disproportionately low. In contrast, MS patients benefit from earlier intervention and access to disease-modifying therapies, improving long-term outcomes.

The complex multisystem nature of these conditions, frequent comorbidities, and the absence of definitive cures drive persistently high health-service utilisation and costs. In ME/CFS, adults incur fourfold higher annual medication costs than those without such an illness, they have more medical tests and GP visits and have roughly double the total annual direct costs. Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) data likewise show heavy health care use, with nearly one in five working-age benefit recipients having an emergency-department visit in the past year and with one-third dispensed ten or more unique medicines. MS is characterised by elevated acute-care use, including potentially avoidable hospitalisations at approximately twice the rate of those without MS, with substantial direct medical costs dominated by disease-modifying therapies. For EDS, the United States (US) ‘claims’ data indicate mean excess annual health costs of US$21,100 for adults and US$17,000 for children versus matched controls. In a US study of FM, compared to matched controls, patients were found to have approximately four times the number of doctor visits, twice the outpatient visits, four times the emergency department visits, and overall, at about three times the total annual cost (US$9,573 vs US$3,291). The condition LC is similarly associated with higher costs and hospital needs. For example, in Israel, for LC patients compared with post-COVID patients without LC, the likelihood of hospitalisation was increased ~2.5-fold, and direct medical costs were up to 1.8-fold more than the post infection controls.

EMPLOYMENT OUTCOMES

Persistent symptoms, fluctuating disease courses, and barriers to workplace physical adaptions drive significant employment disruption across these chronic conditions. Fatigue, pain, and cognitive impairments limit work capacity, while a lack of understanding from employers, stigma surrounding the legitimacy of symptoms, and inadequate workplace flexibility, such as rest breaks or low-stimulation environments, further constrain opportunities for sustained employment. These challenges often result in reduced working hours, necessitate career changes, or require permanent withdrawal from the workforce, particularly when illness onset occurs in early or mid-adulthood, thereby amplifying lifetime income losses and impeding career progression. Meta-analyses and large-scale studies have illustrated the scale of these impacts. In ME/CFS, in two studies 35 and 69% of individuals were unable to maintain employment due to illness-related disability. For LC, pooled data indicate 39% were unable to work 12-months post-infection. In FM, employment rates among women ranged from 34-77% across studies, with similar patterns seen in EDS. In MS, meta-analysis showed a pooled unemployment rate of 36%, with employment declining over time, and early retirement in 18% of cases. Even with improved treatments and workplace adjustments, many with MS still face discrimination, fatigue-related limitations, and eventual workforce exit.

SOCIAL SERVICES

Individuals with complex chronic conditions often require social protection systems because of difficulties in entering and sustaining employment. Despite high levels of need, systemic barriers constrain access. Uncertainty, around the patients’ diagnosis, limited availability of specialist assessments, and inconsistent recognition of the conditions within eligibility frameworks often result in low coverage. Formal disability supports, such as home help, equipment provision, and funded care, are rarely tailored to fatigue- and pain-dominant conditions, leaving many without adequate assistance. By contrast, MS has benefited from clearer clinical pathways and sustained advocacy, enabling more consistent access to disability services. The absence of systematic tracking and coding of ME/CFS, LC, FM, and EDS further compound their invisibility in policy planning and funding. Quantitative evidence illustrates the extent of social service reliance. In Spain, two-thirds of unemployed individuals with ME/CFS were receiving sick leave or disability pensions, while in NZ, 85% of people with ME/CFS remained on income-tested benefits continuously for one year, and nearly half for five years, reflecting sustained economic hardship. A US study reported that 35% of FM patients were in receipt of Social Security Disability payments. For MS, large-scale registry studies in Sweden found that 65% of working-age patients received at least one social protection benefit, with prevalence rising from 33% among those with minimal disability to 99% among those with severe disability. In the US, nearly 30% of working-age individuals with MS rely on social security disability insurance, with transfer payments estimated to cost $6.7 billion annually. These figures highlight both the substantial reliance on welfare and disability supports across these chronic conditions and the stark inequities in recognition and provision that persist between the more established conditions such as MS and those that remain under-recognised.

6. An Aotearoa New Zealand case study: inadequacies and inequities in public health policy

PUBLIC HEALTH POLICY

Health services across NZ are inconsistent in their provision for complex chronic conditions. ME/CFS, EDS, FM, and LC patients face fragmented care pathways, and persistent stigma with limited supportive research funding. In contrast, MS, has benefited from decades of biomedical research and sustained government investment so patients are comparatively well-supported. The clinical trajectory of MS, which is uniquely characterised by its degenerative, progressive nature and association often with premature mortality, can in part explain why there is more dedicated funding. MS care is characterized by specialist neurologist management and good access to publicly funded disease-modifying therapies.

Certain forms of EDS and some cases of the organ damaged subgroup of LC can in rare cases result in multi-system organ failure and early death. In contrast, the major ME/CFS-like subgroup of LC, ME/CFS and EDS are lifelong but non-progressive conditions. Despite this, the daily burden of the conditions is substantial. A pivotal study found that ME/CFS reported the lowest health-related quality of life (HRQoL) scores among 20 chronic conditions that included MS. ME/CFS in NZ lacks a nationally integrated care pathway yet affects up to an estimated 65,000 people (pre-pandemic estimates of 1 in 254 adults and 1 in 134 youth, compared to MS of 1 in 1,000 people). This absence of an integrated care pathway results in a “postcode” lottery, where access to services varies significantly across regions of the country. General Practitioner education remains inconsistent, and outdated guidelines still advocate Graded Exercise Therapy (GET) as being the preferred treatment, despite being removed from international best practice recommendations. Unlike MS, which benefits from specialist neurologist oversight, ME/CFS is largely a self-managed condition in NZ, due to lack of consistent medical education and standards. Patients mostly rely on their own research and on support from national and regional non-profit organisations, due to the absence of formal care pathways and limited specialist input. EDS and FM are similarly underserved. EDS often goes misdiagnosed or dismissed due to limited clinician training and awareness. Although organisations like EDSNZ provide support and resources, there is no formal national clinical pathway, and few specialists are trained in hypermobility spectrum disorders. While the Aotearoa New Zealand EDS Guideline V provides a valuable framework, it has not been formally adopted by Health NZ (Te Whatu ora), or integrated into standard clinical pathways, despite an overall assurance rare disorders will be included. The guidelines are primarily used by physiotherapists who have a special interest in hypermobility spectrum disorders. The most abundant chronic condition, FM affects approximately 1 in 50 New Zealanders. Diagnosis is challenging due to the absence of definitive biomarkers. Support is provided by Arthritis NZ, but care remains inconsistent, and patients have difficulty accessing appropriate treatment and are often not taken seriously by healthcare providers.

Systemic challenges in chronic pain management across NZ have been highlighted, particularly for the indigenous Māori, and for disabled populations. Patients with chronic pain, including those with FM, are often underrepresented in tertiary pain services, yet present with more severe symptoms and have high unmet needs. Health workers also report a lack of holistic and informed care. Long COVID presents a large new challenge for NZ with 200,000 likely affected, as deduced from international documented incidence. The Ministry of Health has developed clinical rehabilitation guidelines and funded some research initiatives, including the LOGIC study and a national registry but there are no dedicated clinics or inpatient services for severe cases, and care is fragmented across primary care with limited specialist input.

Although the Aotearoa New Zealand Government Policy Statement, Health 2024–2027, has a vision of equitable access to healthcare regardless of geographic location, evidence indicates for those living with ME/CFS, EDS, FM, and LC, this vision is yet to be realised. These conditions are underfunded, inadequately researched, and not well recognised, resulting in systemic inequities contradicting the policy’s stated goals. Without reforms of national guidelines, clinician education, and dedicated funding the health system will continue to fail a significant and growing subgroup of the population. Several European and other countries offer more progressive care models. For example, for ME/CFS the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines 2021 recommend pacing and symptom-led care and no longer recommend Graded Exercise Therapy (GET). Norway has national guidelines for ME/CFS that include biomedical research funding and standardised care pathways and Australia now has a national LC plan that includes coordinated care pathways, multidisciplinary clinics, and a disease register. The Netherlands and Italy have integrated care models for ME/CFS and FM that focus on patient-centred rehabilitation and social support.

INADEQUACIES IN PUBLIC HEALTH SUPPORT

In NZ, access to social services is marked for individuals with ME/CFS, LC, EDS, FM, and MS by systemic inequities and inconsistent recognition of disability. For example, ME/CFS and LC are classified as chronic illnesses rather than disabilities, which excludes access to disability supports through the social agency Whaikaha – Ministry of Disabled People under the Ministry of Social Development (MSD), despite the conditions meeting the government’s own definition of disability. Although Health NZ (Te Whatu Ora) asserts that individuals with ME/CFS and LC can access support through a Long-Term Conditions (LTC) framework, this is not reflected in practice. The LTC pathway sets high eligibility thresholds, often requiring individuals to demonstrate extreme levels of need such as requiring 24/7 care before any support can be granted. Even then, the assistance provided is minimal, typically capped at three hours of care per day. This limited provision excludes those with moderate disability, who could benefit significantly from early intervention services such as home help, respite care and mobility aids.

The current social support system acts as an “ambulance at the bottom of the cliff” rather than functioning as a preventative “fence at the top”, intervening only when patients reach crisis levels. This crisis reactive model exacerbates disease progression and increases long-term healthcare costs. The inadequacy of formal social support places a disproportionate burden on family members, who assume primary caregiving roles. This affects household income, limits career opportunities, and contributes to caregiver burnout. Studies show that over 30% of family caregivers for those affected in NZ have had to give up paid employment, and many have high levels of stress, depression, and financial hardship. Moreover, the lack of training, respite, and systemic support for such informal caregivers increases the risk of inadequate care for the affected patient. This is most concerning for the more severely affected patients with complex needs, such as ME/CFS patients who may be bedbound, unable to speak or have extreme hypersensitivity to environmental stimuli. Addressing these gaps requires a shift toward proactive, equitable, and integrated social support care models that recognize ME/CFS and LC as disabling conditions. Patients with EDS and FM face similar barriers due to diagnostic ambiguity and lack of formal recognition within disability frameworks. Although FM can significantly impair daily functioning and quality of life, it is also not automatically classified as a disability in NZ. Eligibility for support requires extensive documentation and proof of long-term impact, which many patients struggle to obtain. Consequently, individuals with these conditions often are excluded from social support.

How does this compare with European countries?

MS care in Sweden is highly structured, well-resourced, and supported by national registries and multidisciplinary teams. The Swedish MS Association (Svenska MS-sällskapet) coordinates care across the country, involving neurologists, rehabilitation clinicians, nurses, occupational therapists, and psychologists. MS patients benefit from dedicated MS centres and multidisciplinary rehabilitation. They have access to disease-modifying therapies and are integrated into the Swedish MS registry. In contrast, ME/CFS care in Sweden remains fragmented and underdeveloped. Although the National Board of Health and Welfare acknowledges ME/CFS as a serious and disabling condition, it lacks the infrastructure and recognition afforded to MS. The key challenges include limited clinics and the use of controversial treatment models, the absence of a national registry, and inconsistent access to disability benefits. There are continual debates about classification of ME/CFS, with some health authorities still viewing it through a psychosomatic lens. In Germany, LC rehabilitation clinics have set up highly supportive integrated interdisciplinary teams that include social workers, psychologists, and occupational therapists so the medical and social needs of patients can be fully addressed. Elsewhere, the Canadian Guidelines for Post-COVID-19 Condition (CAN-PCC), emphasise patient-led input and coordination across health and social services. These guidelines aim to inform policy and practice using evidence-based recommendations that include social support as a core component of care. Such international frameworks highlight the importance of recognising the complex chronic conditions as disabling and integrating social services into care pathways. Although social services for FM and EDS are also inconsistent globally, some countries unlike NZ offer better recognition and more structured frameworks, for example in Canada, UK, and Germany there is financial support, legal advocacy and protections, caregiver assistance, and inclusion in education/employment policies.

ACCESS TO FINANCIAL SUPPORT

In NZ, individuals with ME/CFS, EDS, FM, and LC face significant financial hardship, compounded by limited access to formal financial support. A report by the Aotearoa NZ ME Society (ANZMES) estimates ME/CFS imposes extra annual household costs for a family of between $35,000 and $45,000 (2017 data), primarily due to lost income, medical expenses, and caregiving burdens. Financial relief through the social agency Work and Income New Zealand remains minimal. Eligibility for benefits such as a Supported Living Payment or Disability Allowance is complex and inconsistently applied, often requiring extensive documentation and medical certification. Patients with EDS and FM encounter similar barriers. Patients with MS are more likely to receive financial support through the Ministry of Social Development, including access to the Supported Living Payment and other targeted benefits.

In Europe, several countries offer more inclusive and structured financial support systems. In Finland, people are assessed by functional impairment rather than by diagnosis alone. In the United Kingdom, the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) scheme includes ME/CFS and FM under its functional impairment criteria. It is not means-tested and is awarded on the impact of symptoms on daily living and mobility. In 2024, over 136,000 individuals with FM were receiving PIP, with a 62% success rate for claims—higher than the average for all other conditions. For MS, in the UK, functional impairment also gives access to PIP, but additionally patients benefit from government-funded support for equipment and transport assistance to remain in employment, and housing benefit and council tax reductions for required housing adaptations. Likewise in Finland, financial support for MS is substantial, with rehabilitation subsidies, disability benefits or pensions, carers allowance and information care support paid to family members providing in-home care. Those with ME/CFS could apply based on functional impairment, but this condition is not explicitly mentioned like MS.

7. Conclusion

A significant feature of the five chronic conditions discussed here is the number of overlapping symptoms shared amongst them, despite the distinct core nature of each condition. These are often interpreted differently depending on the condition under study. There would seem to be benefit for all conditions from discovery of an effective treatment for an overlapping symptom. This suggests a need for a more integrated approach to consider all chronic conditions as different variations in the response of susceptible individuals to a major stressor on body physiology, whether it be directly from a genetic cause, or genetically linked but silent until an external stressor triggers the response of the condition. At its extreme, this concept would consider the conditions as different clinical subtypes representing human physiology’s response to the initiating event, whether it be internal or external, influenced by the affected person’s genetic background that might influence which clinical phenotype results. Therefore, by not regarding each condition in its own silo but rather more holistically together as an overlapping set of conditions might better progress our understanding and management of them.

For each of the chronic conditions, ME/CFS, LC, FM, EDS and MS, there is a lack of early diagnosis tests that would enable strategies to be put in place rapidly to manage the conditions from their early stages. Ideally these would be tests that would be accessible to all patients and their clinicians. If there were tests for condition-specific molecular changes that could be rapidly analysed even the patients with the most challenging of the conditions might be helped significantly. We have shown there are epigenetic DNA methylome changes specific for ME/CFS and for LC that are present in each patient of small cohorts tested. Whether there are specific epigenetic changes for each of the other chronic conditions remains to be determined. Such changes have the potential to be captured for a readily accessible early diagnostic test in community pathology laboratories. Comparative tests among cohorts with each condition as we have carried out with ME/CFS and LC would be beneficial. It could result in a test that would at least avoid misdiagnoses that commonly occur at present.

8. Future Directions

Most studies of pathophysiology of the chronic conditions have used people at different stages of their disease and at single time points. Stage specific research studies that are also longitudinal so that the changes in various classes of molecules can be mapped as the condition progresses would significantly advance our understanding of the nature of these chronic conditions. Artificial intelligence can now access huge amounts of decoded clinical data and use of this facility might prove a huge boost for clinicians not well versed in the conditions when faced with the challenge of a complex new patient, both for diagnosis, and management. It would be less likely a patient would be dismissed without a diagnosis as so often happens today.

What is clear from a comparison of these chronic conditions is that MS is far ahead of the others in being universally accepted and excellent public health policy has been developed for support and management. MS patients have relatively good access to social services and financial support. An integrated consideration of the chronic diseases might facilitate more comprehensive care pathways and facilities for patients with the other illnesses and approach that ‘gold standard’ available for MS as a successful model.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

None.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References

1. Shepherd C. ME/CF/PVFS. The MEA Clinical & Research Guide. An Exploration of the Key Clinical Issues. 13th ed. The ME association, UK; 2022:316.

2. Staff M. AN OUTBREAK of encephalomyelitis in the Royal Free Hospital Group, London, in 1955. Br Med J. Oct 19 1957;2(5050):895-904.

3. Levine PH, Jacobson S, Pocinki AG, et al. Clinical, epidemiologic, and virologic studies in four clusters of the chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Intern Med. Aug 1992;152(8):1611-6.

4. Vallings R. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome M.E.Symptoms, Diagnosis, Management. Calico Publishing; 2020.

5. Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. Mar 2023;21(3):133-146. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2

6. Gentilotti E, Górska A, Tami A, et al. Clinical phenotypes and quality of life to define post-COVID-19 syndrome: a cluster analysis of the multinational, prospective ORCHESTRA cohort. eClinicalMedicine. 2023/08/01/ 2023;62:102107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102107

7. Tate WP, Walker MOM, Peppercorn K, Blair ALH, Edgar CD. Towards a Better Understanding of the Complexities of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis /Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Long COVID. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5124.

8. Komaroff AL, Lipkin WI. ME/CFS and Long COVID share similar symptoms and biological abnormalities: road map to the literature. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1187163. doi:10.3389/ fmed.2023.1187163

9. Eckey M, Li P, Morrison B, et al. Patient-reported treatment outcomes in ME/CFS and long COVID. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Jul 15 2025;122(28): e2426874122. doi:10.1073/pnas.2426874122

10. Marshall-Gradisnik S, Eaton-Fitch N. Understanding myalgic encephalomyelitis. Science. Sep 9 2022;37 7(6611):1150-1151. doi:10.1126/science.abo1261

11. Peppercorn K, Edgar CD, Kleffmann T, Tate WP. A pilot study on the immune cell proteome of long COVID patients shows changes to physiological pathways similar to those in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Sci Rep. Dec 12 2023;13(1):22068. doi:10.1038/s4159 8-023-49402-9

12. Peppercorn K, ; Edgar, C.; Al Momani, S,; Rodger, E. J.; Tate, W.P.; Chatterjee, A. Application of DNA methylome analysis to patients with ME/CFS. Methods in Molecular Biology. Spinger; 2025.

13. Shah KM, Shah RM, Sawano M, et al. Factors Associated with Long COVID Recovery among US Adults. Am J Med. Sep 2024;137(9):896-899. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.04.017

14. Ballouz T, Menges D, Anagnostopoulos A, et al. Recovery and symptom trajectories up to two years after SARS-CoV-2 infection: population based, longitudinal cohort study. Bmj. May 31 2023;381:e074425. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-074425

15. Hartung TJ, Bahmer T, Chaplinskaya-Sobol I, et al. Predictors of non-recovery from fatigue and cognitive deficits after COVID-19: a prospective, longitudinal, population-based study. EClinicalMedicine. Mar 2024;69:102456. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102456

16. Al-Aly Z, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat Med. Aug 2024;30(8):2148-2164. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

17. Walitt B, Nahin RL, Katz RS, Bergman MJ, Wolfe F. The Prevalence and Characteristics of Fibromyalgia in the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138024. doi:10.13 71/journal.pone.0138024

18. Arnold LM, Fan J, Russell IJ, et al. The fibromyalgia family study: a genome-wide linkage scan study. Arthritis Rheum. Apr 2013;65(4):1122-8. doi:10.1002/art.37842

19. Rahman MS, Winsvold BS, Chavez Chavez SO, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies RNF123 locus as associated with chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain. Ann Rheum Dis. Sep 2021;80 (9):1227-1235. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219624

20. Pan Q, Cai T, Tao Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel genetic variants associated with widespread pain in the UK Biobank (N = 172,230). Mol Pain. Jan-Dec 2025;21:1744806 9251346603. doi:10.1177/17448069251346603

21. Das S, Taylor K, Kozubek J, Sardell J, Gardner S. Genetic risk factors for ME/CFS identified using combinatorial analysis. J Transl Med. Dec 14 2022; 20(1):598. doi:10.1186/s12967-022-03815-8

22. Taylor K, Pearson M, Das S, et al. Genetic risk factors for severe and fatigue dominant long COVID and commonalities with ME/CFS identified by combinatorial analysis. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2023/11/01 2023;21(1):775. doi:10.1186 /s12967-023-04588-4

23. Boutin T, Bretherick A, Dibble J, et al. Initial findings from the DecodeME genome-wide association study of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. 2025.

24. Cortini F, Villa C. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and epilepsy: An updated review. Seizure. Apr 2018;57:1-4. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2018.02.013

25. Malfait F, Francomano C, Byers P, et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. Mar 2017;175(1):8-26. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31552

26. Lawrence EJ. The clinical presentation of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Adv Neonatal Care. Dec 2005;5(6):301-14. doi:10.1016/j.adnc.2005.09.006

27. Mudie K, Ramiller A, Whittaker S, Phillips LE. Do people with ME/CFS and joint hypermobility represent a disease subgroup? An analysis using registry data. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1324879. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1324879

28. Malfait F, Wenstrup RJ, De Paepe A. Clinical and genetic aspects of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, classic type. Genet Med. Oct 2010;12(10):597-605. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181eed412

29. Bakalidou D, Giannopapas V, Giannopoulos S. Thoughts on Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Cureus. Jul 2023;15(7):e42146. doi:10.7759/cureus.42146

30. Travers BS, Tsang BK, Barton JL. Multiple sclerosis: Diagnosis, disease-modifying therapy and prognosis. Aust J Gen Pract. Apr 2022;51 (4):199-206. doi:10.31128/ajgp-07-21-6103

31. Venkatesan A, Johnson RT. Infections and multiple sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;122: 151-71. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-52001-2.00007-8

32. Riise T, Mohr DC, Munger KL, et al. Stress and the risk of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. May 31 2011;76(22):1866-71. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821d74c5

33. Mohr DC, Hart SL, Julian L, Cox D, Pelletier D. Association between stressful life events and exacerbation in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Bmj. Mar 27 2004;328(7442):731. doi:10.1136/bmj .38041.724421.55

34. Tate W, Walker M, Sweetman E, et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Neuroinflammation in ME/CFS and Long COVID to Sustain Disease and Promote Relapses. Front Neurol. 2022;13:877772. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.877772

35. Sharma S, Hodges LD, Peppercorn K, et al. Precision Medicine Study of Post-Exertional Malaise Epigenetic Changes in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Patients During Exercise. Int J Mol Sci. Sep 3 2025;26(17)doi:10.33 90/ijms26178563

36. Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. Oct 25 2008;372(9648):1502-17. doi:10.10 16/s0140-6736(08)61620-7

37. Wootla B, Eriguchi M, Rodriguez M. Is multiple sclerosis an autoimmune disease? Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:969657. doi:10.1155/2012/969657

38. Vilisaar J, Harikrishnan S, Suri M, Constantinescu CS. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and multiple sclerosis: a possible association. Mult Scler. May 2008;14(4): 567-70. doi:10.1177/1352458507083187

39. Mar PL, Raj SR. Neuronal and hormonal perturbations in postural tachycardia syndrome. Front Physiol. 2014;5:220. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00220

40. van Campen C, Rowe PC, Visser FC. Low Sensitivity of Abbreviated Tilt Table Testing for Diagnosing Postural Tachycardia Syndrome in Adults With ME/CFS. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:349. doi:10.3389/fped.2018.00349

41. Roma M, Marden CL, De Wandele I, Francomano CA, Rowe PC. Postural tachycardia syndrome and other forms of orthostatic intolerance in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Auton Neurosci. Dec 2018;215:89-96. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2018.02.006

42. Adamec I, Lovrić M, Žaper D, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome associated with multiple sclerosis. Auton Neurosci. Jan 2013;173 (1-2):65-8. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2012.11.009

43. Staud R. Autonomic dysfunction in fibromyalgia syndrome: postural orthostatic tachycardia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. Dec 2008;10(6):463-6. doi:10.100 7/s11926-008-0076-8

44. Theoharides TC, Tsilioni I, Ren H. Recent advances in our understanding of mast cell activation – or should it be mast cell mediator disorders? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. Jun 2019;15(6):639-656. doi:10.1080/1744666x.2019.1596800

45. Afrin LB, Ackerley MB, Bluestein LS, et al. Diagnosis of mast cell activation syndrome: a global “consensus-2”. Diagnosis (Berl). May 26 2021;8(2):137-152. doi:10.1515/dx-2020-0005

46. Hatziagelaki E, Adamaki M, Tsilioni I, Dimitriadis G, Theoharides TC. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis /Chronic Fatigue Syndrome-Metabolic Disease or Disturbed Homeostasis due to Focal Inflammation in the Hypothalamus? J Pharmacol Exp Ther. Oct 2018;367(1):155-167. doi:10.1124/jpet.118.250845

47. Theoharides TC, Tsilioni I, Arbetman L, et al. Fibromyalgia syndrome in need of effective treatments. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. Nov 2015;355 (2):255-63. doi:10.1124/jpet.115.227298

48. Akin C. Mast cell activation syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Aug 2017;140(2):349-355. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.06.007

49. Nguyen T, Johnston S, Chacko A, et al. Novel characterisation of mast cell phenotypes from peripheral blood mononuclear cells in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis patients. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. Jun 2017;35(2):75-81. doi:10.12932/ap0771

50. Mandarano AH, Maya J, Giloteaux L, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients exhibit altered T cell metabolism and cytokine associations. J Clin Invest. Mar 2 2020; 130(3):1491-1505. doi:10.1172/jci132185

51. Walker MOM, Peppercorn K, Kleffmann T, Edgar CD, Tate WP. An understanding of the immune dysfunction in susceptible people who develop the post-viral fatigue syndromes Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Long COVID. Medical Research Archives. 2023-07-06 2023;11(7.1)doi:10.18103/mra.v11i7.1.4083

52. Walitt B, Singh K, LaMunion SR, et al. Deep phenotyping of post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Nat Commun. Feb 21 2024;15(1):907. doi:10.1038/ s41467-024-45107-3

53. Eaton-Fitch N, Rudd P, Er T, et al. Immune exhaustion in ME/CFS and long COVID. JCI Insight. Oct 22 2024;9(20)doi:10.1172/jci.insight.183810

54. Cervia-Hasler C, Brüningk SC, Hoch T, et al. Persistent complement dysregulation with signs of thromboinflammation in active Long Covid. Science. Jan 19 2024;383(6680):eadg7942. doi:10. 1126/science.adg7942

55. Altmann DM, Whettlock EM, Liu S, Arachchillage DJ, Boyton RJ. The immunology of long COVID. Nat Rev Immunol. Oct 2023;23(10): 618-634. doi:10.1038/s41577-023-00904-7

56. Yin K, Peluso MJ, Luo X, et al. Long COVID manifests with T cell dysregulation, inflammation and an uncoordinated adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol. Feb 2024;25(2):218-225. doi:10.1038/s41590-023-01724-6

57. Clauw D, Sarzi-Puttini P, Pellegrino G, Shoenfeld Y. Is fibromyalgia an autoimmune disorder? Autoimmun Rev. Jan 2024;23(1):103424. doi:10.1016/j.autrev. 2023.103424

58. Paroli M, Gioia C, Accapezzato D, Caccavale R. Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Infection in Fibromyalgia: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. May 29 2024;25(11)doi:10.3390/ijms25115922

59. International statistical classification of diseases, injuries, and causes of death. (World Health Organisation) (1969).

60. Nakatomi Y, Mizuno K, Ishii A, et al. Neuroinflammation in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: An (1)(1)C-(R)-PK11195 PET Study. J Nucl Med. Jun 2014; 55(6):945-50. doi:10.2967/jnumed.113.131045

61. Bynke A, Julin P, Gottfries CG, et al. Autoantibodies to beta-adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) patients – A validation study in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid from two Swedish cohorts. Brain Behav Immun Health. Aug 2020;7:100107. doi:10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100107

62. Talkington GM, Kolluru P, Gressett TE, et al. Neurological sequelae of long COVID: a comprehensive review of diagnostic imaging, underlying mechanisms, and potential therapeutics. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1465787. doi:10.3389/fneur .2024.1465787

63. Peppercorn K, Sharma S, Edgar CD, et al. Comparing DNA Methylation Landscapes in Peripheral Blood from Myalgic Encephalomyelitis /Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Long COVID Patients. Int J Mol Sci. Jul 10 2025;26(14)doi:10. 3390/ijms26146631

64. Clauw DJ, Arnold LM, McCarberg BH. The science of fibromyalgia. Mayo Clin Proc. Sep 2011;86(9):907-11. doi:10.4065/mcp.2011.0206

65. Fitzcharles MA, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ, et al. Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. Lancet. May 29 2021;397(10289):2098-2110. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00392-5

66. Becker S, Schweinhardt P. Dysfunctional neurotransmitter systems in fibromyalgia, their role in central stress circuitry and pharmacological actions on these systems. Pain Res Treat. 2012; 2012:741746. doi:10.1155/2012/741746

67. Fernandez A, Jaquet M, Aubry-Rozier B, et al. Functional neurological signs in hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and hypermobile spectrum disorders with suspected neuropathic pain. Brain Behav. Feb 2024;14(2):e3441. doi:10.1002/brb3.3441

68. Oudejans E, Luchicchi A, Strijbis EMM, Geurts JJG, van Dam AM. Is MS affecting the CNS only? Lessons from clinic to myelin pathophysiology. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. Jan 2021;8 (1)doi:10.1212/nxi.0000000000000914

69. Holden S, Maksoud R, Eaton-Fitch N, et al. A systematic review of mitochondrial abnormalities in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome/systemic exertion intolerance disease. J Transl Med. Jul 29 2020;18(1):290. doi:10.1186/s1 2967-020-02452-3

70. Annesley SJ, Missailidis D, Heng B, Josev EK, Armstrong CW. Unravelling shared mechanisms: insights from recent ME/CFS research to illuminate long COVID pathologies. Trends Mol Med. May 2024;30(5):443-458. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2024.02.003

71. Syed AM, Karius AK, Ma J, Wang PY, Hwang PM. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Physiology (Bethesda). Jul 1 2025;40(4):0. doi:10. 1152/physiol.00056.2024

72. Sweetman E, Kleffmann T, Edgar C, et al. A SWATH-MS analysis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis /Chronic Fatigue Syndrome peripheral blood mononuclear cell proteomes reveals mitochondrial dysfunction. J Transl Med. Sep 24 2020;18(1):365. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02533-3

73. Missailidis D, Annesley SJ, Allan CY, et al. An Isolated Complex V Inefficiency and Dysregulated Mitochondrial Function in Immortalized Lymphocytes from ME/CFS Patients. Int J Mol Sci. Feb 6 2020;21(3)doi:10.3390/ijms21031074

74. Arnold DL, Bore PJ, Radda GK, Styles P, Taylor DJ. Excessive intracellular acidosis of skeletal muscle on exercise in a patient with a post-viral exhaustion/fatigue syndrome. A 31P nuclear magnetic resonance study. Lancet. Jun 23 1984;1(8 391):1367-9. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91871-3

75. Naviaux RK, Naviaux JC, Li K, et al. Metabolic features of chronic fatigue syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Sep 13 2016;113(37):E5472-80. doi:10.1073/pnas.1607571113

76. Fluge Ø, Mella O, Bruland O, et al. Metabolic profiling indicates impaired pyruvate dehydrogenase function in myalgic encephalopathy/chronic fatigue syndrome. JCI Insight. Dec 22 2016;1(21):e89376. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.89376

77. Germain A, Ruppert D, Levine SM, Hanson MR. Metabolic profiling of a myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome discovery cohort reveals disturbances in fatty acid and lipid metabolism. Mol Biosyst. Jan 31 2017; 13(2):371-379. doi:10.1039/c6mb00600k

78. Mueller C, Lin JC, Sheriff S, Maudsley AA, Younger JW. Evidence of widespread metabolite abnormalities in Myalgic encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome: assessment with whole-brain magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Brain Imaging Behav. Apr 2020;14(2):562-572. doi:10.1007/s116 82-018-0029-410.1007/s11682-018-0029-4.

79. Thapaliya K, Marshall-Gradisnik S, Eaton-Fitch N, et al. Imbalanced Brain Neurochemicals in Long COVID and ME/CFS: A Preliminary Study Using MRI. Am J Med. Mar 2025;138(3):567-574.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.04.007

80. Macchi C, Giachi A, Fichtner I, et al. Mitochondrial function in patients affected with fibromyalgia syndrome is impaired and correlates with disease severity. Sci Rep. Dec 4 2024;14(1): 30247. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-81298-x

81. Jung YH, Kim H, Seo S, et al. Central metabolites and peripheral parameters associated neuroinflammation in fibromyalgia patients: A preliminary study. Medicine (Baltimore). Mar 31 2023;102(13):e33305. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000033305

82. Davis L, Higgs M, Snaith A, et al. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism, energy production, and oxidative stress in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, Gulf War Syndrome and fibromyalgia. Front Neurosci. 2025;19:1498981. doi:10.3389/ fnins.2025.1498981

83. Shirvani P, Shirvani A, Holick MF. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Its Potential Molecular Interplay in Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: A Scoping Review Bridging Cellular Energetics and Genetic Pathways. Curr Issues Mol Biol. Feb 19 2025;47 (2)doi:10.3390/cimb47020134

84. Ravera S, Panfoli I, Calzia D, et al. Evidence for aerobic ATP synthesis in isolated myelin vesicles. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. Jul 2009;41(7):1581-91. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2009.01.009

85. Ravera S, Panfoli I, Aluigi MG, Calzia D, Morelli A. Characterization of Myelin Sheath F(o)F(1)-ATP synthase and its regulation by IF(1). Cell Biochem Biophys. Mar 2011;59(2):63-70. doi:10.1007/s1201 3-010-9112-1

86. Morelli AM, Ravera S, Panfoli I. The aerobic mitochondrial ATP synthesis from a comprehensive point of view. Open Biol. Oct 2020;10(10):200224. doi:10.1098/rsob.200224

87. Mishra G, Townsend KL. The metabolic and functional roles of sensory nerves in adipose tissues. Nat Metab. Sep 2023;5(9):1461-1474. doi: 10.1038/s42255-023-00868-x

88. Greeck VB, Williams SK, Haas J, Wildemann B, Fairless R. Alterations in Lymphocytic Metabolism-An Emerging Hallmark of MS Pathophysiology? Int J Mol Sci. Jan 20 2023;24(3)doi:10.3390/ijms24032094

89. König RS, Albrich WC, Kahlert CR, et al. The Gut Microbiome in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) /Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). Front Immunol. 2021;12:628741. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.628741

90. El-Sehrawy A, Ayoub, II, Uthirapathy S, et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a narrative review of an emerging field. Eur J Transl Myol. Mar 31 2025;35(1)doi:10.4081/ejtm.2025.13690

91. Jurek JM, Castro-Marrero J. A Narrative Review on Gut Microbiome Disturbances and Microbial Preparations in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Implications for Long COVID. Nutrients. May 21 2024;16(11)doi:10.3390/nu16111545

92. Fallah A, Sedighian H, Kachuei R, Fooladi AAI. Human microbiome in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS). Curr Res Microb Sci. 2025;8:10 0324. doi:10.1016/j.crmicr.2024.100324

93. Minerbi A, Khoutorsky A, Shir Y. Decoding the connection: unraveling the role of gut microbiome in fibromyalgia. Pain Rep. Feb 2025;10(1):e1224. doi:10.1097/pr9.0000000000001224

94. Choudhary A, Fikree A, Ruffle JK, et al. A machine learning approach to stratify patients with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome/ hypermobility spectrum disorders according to disorders of gut brain interaction, comorbidities and quality of life. Neurogastroenterol Motil. Jan 2025;37(1):e14957. doi:10.1111/nmo.14957

95. Parodi B, Kerlero de Rosbo N. The Gut-Brain Axis in Multiple Sclerosis. Is Its Dysfunction a Pathological Trigger or a Consequence of the Disease? Front Immunol. 2021;12:718220. doi:10. 3389/fimmu.2021.718220

96. Sharifa M, Ghosh T, Daher OA, et al. Unraveling the Gut-Brain Axis in Multiple Sclerosis: Exploring Dysbiosis, Oxidative Stress, and Therapeutic Insights. Cureus. Oct 2023;15(10):e47 058. doi:10.7759/cureus.47058

97. Mohsen E, Haffez H, Ahmed S, Hamed S, El-Mahdy TS. Multiple Sclerosis: A Story of the Interaction Between Gut Microbiome and Components of the Immune System. Mol Neurobiol. Jun 2025;6 2(6):7762-7775. doi:10.1007/s12035-025-04728-5

98. Carruthers BM, Jain AK, De Meirleir KL, et al. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 2003/01/01 2003;11(1):7-115. doi:10.1300/J092v11n01_02

99. Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J Intern Med. Oct 2011;270(4): 327-38. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x

100. Vallings R. How a Clinician Makes a Diagnosis for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Methods Mol Biol. 2025;292 0:3-11. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-4498-0_1

101. WHO. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus, 6 October 2021. 2021.

102. RECOVER. RECOVER: Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery. NIH. Accessed 14 October 2025, 2025. https://recovercovid.org

103. Häuser W, Perrot S, Sommer C, Shir Y, Fitzcharles MA. Diagnostic confounders of chronic widespread pain: not always fibromyalgia. Pain Rep. May 2017;2(3):e598. doi:10.1097/pr9.000000 0000000598

104. Jones EA, Asaad F, Patel N, Jain E, Abd-Elsayed A. Management of Fibromyalgia: An Update. Biomedicines. Jun 6 2024;12(6)doi:10.339 0/biomedicines12061266

105. Hardmeier M, Leocani L, Fuhr P. A new role for evoked potentials in MS? Repurposing evoked potentials as biomarkers for clinical trials in MS. Mult Scler. Sep 2017;23(10):1309-1319. doi:10.117 7/1352458517707265

106. Society TNMS. Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis (RRMS). Accessed 14 Oct 2025, 2025. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/understanding-ms/what-is-ms/types-of-ms/relapse-remitting-ms

107. Kingdon CC, Bowman EW, Curran H, Nacul L, Lacerda EM. Functional Status and Well-Being in People with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Compared with People with Multiple Sclerosis and Healthy Controls. Pharmacoecon Open. Dec 2018;2(4):381-392. doi:10.1007/s41669-018-0071-6

108. Nacul LC, Lacerda EM, Campion P, et al. The functional status and well being of people with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and their carers. BMC Public Health. May 27 2011;11:402. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-402

109. Bae J, Lin JS. Healthcare Utilization in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Analysis of US Ambulatory Healthcare Data, 2000-2009. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:185. doi:10 .3389/fped.2019.00185

110. Pheby DFH, Araja D, Berkis U, et al. A Literature Review of GP Knowledge and Understanding of ME/CFS: A Report from the Socioeconomic Working Group of the European Network on ME/CFS (EUROMENE). Medicina (Kaunas). Dec 24 2020;57(1)doi:10.3390/medicina57010007

111. Gendelman O, Shapira R, Tiosano S, et al. Utilisation of healthcare services and drug consumption in fibromyalgia: A cross-sectional analysis of the Clalit Health Service database. Int J Clin Pract. Nov 2021;75(11):e14729. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14729

112. Jones JT, Black WR, Cogan W, Callen E. Resource utilization and multidisciplinary care needs for patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Mol Genet Genomic Med. Nov 2022;10(11):e2057. doi:10.1002/mgg3.2057

113. O’Sullivan S. It’s all in your head: Stories from the frontline of psychosomatic illness. Random House; 2016.

114. Valdez AR, Hancock EE, Adebayo S, et al. Estimating Prevalence, Demographics, and Costs of ME/CFS Using Large Scale Medical Claims Data and Machine Learning. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:412. doi:10.3389/fped.2018.00412

115. Goodin DS, Frohman EM, Garmany GP, Jr., et al. Disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the MS Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines [RETIRED]. Neurology. Jan 22 2002;58(2):169-78. doi:10.1212/wnl.58.2.169

116. Hauser SL, Cree BAC. Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. Am J Med. Dec 2020;133(12): 1380-1390.e2. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.05.049

117. Jason LA, Benton MC, Valentine L, Johnson A, Torres-Harding S. The economic impact of ME/ CFS: individual and societal costs. Dyn Med. Apr 8 2008;7:6. doi:10.1186/1476-5918-7-6

118. Bowden N, McLeod, K., Anns, F., Catchpole, L., Charlton, F., Taylor, B. S., Vallings, R., Vu, H., Tate, W. Health, Labour Market, And Social Service Outcomes For People With Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome On A Health Or Disability Related Benefit: An Aotearoa | New Zealand Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study Using The Integrated Data Infrastructure. OSF Preprints. 2025;

119. Khan G, Hashim MJ. Epidemiology of Multiple Sclerosis: Global, Regional, National and Sub-National-Level Estimates and Future Projections. J Epidemiol Glob Health. Feb 10 2025;15(1):21. doi:10.1007/s44197-025-00353-6

120. Schubart JR, Mills SE, Francomano CA, Stuckey-Peyrot H. A qualitative study of pain and related symptoms experienced by people with Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1291189. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1291189

121. Berger A, Dukes E, Martin S, Edelsberg J, Oster G. Characteristics and healthcare costs of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Int J Clin Pract. Sep 2007;61(9):1498-508. doi:10.1111/j.174 2-1241.2007.01480.x

122. Tene L, Bergroth T, Eisenberg A, David SSB, Chodick G. Risk factors, health outcomes, healthcare services utilization, and direct medical costs of patients with long COVID. Int J Infect Dis. Mar 2023;128:3-10. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2022.12.002

123. Palstam A, Mannerkorpi K. Work Ability in Fibromyalgia: An Update in the 21st Century. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2017;13(3):180-187. doi:10.2174/ 1573397113666170502152955

124. Taylor RR, Kielhofner GW. Work-related impairment and employment-focused rehabilitation options for individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome: A review. Journal of Mental Health. 2005/06/01 2005;14(3):253-267. doi:10.1080/09638230500136571

125. Bøe Lunde HM, Telstad W, Grytten N, et al. Employment among patients with multiple sclerosis-a population study. PLoS One. 2014;9(7): e103317. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103317

126. Collin SM, Crawley E, May MT, Sterne JA, Hollingworth W. The impact of CFS/ME on employment and productivity in the UK: a cross-sectional study based on the CFS/ME national outcomes database. BMC Health Serv Res. Sep 15 2011;11:217. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-217