Forensic Significance of Human Bite Marks in Skin

Assessment and classification of the forensic significance of human bite marks in skin

Douglas R Sheasby BDS, DDS, MFFLM1

- Honorary Clinical Senior Lecturer in Forensic Odontology, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 November 2025

CITATION: Sheasby, DR., 2025. Assessment and classification of the forensic significance of human bite marks in skin. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(11). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i11.7035

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i11.7035

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

The forensic significance of a bite mark is a relevant factor in the analysis of human bite marks in skin and comparison with teeth. The interpretation of the causal dentition’s class and individual characteristics forms the basis for assessing a bite mark’s forensic significance. The paucity of scientific research in the assessment of forensic significance is an important limiting factor in bite mark analysis and in justifying the comparison of a bite mark with teeth. An evidence-based rationale for assessing and classifying the forensic significance of human bite marks in skin is examined and a limited empirical classification is proposed.

Keywords: Bite mark analysis and comparison; Forensic significance; Classification.

Introduction

The challenges facing the analysis of human bite marks in skin and comparison with teeth arise from the nature of skin and the action of biting producing distorted, partial representations of the anterior dentition’s characteristics. Specifically, unquantified distortion in bite marks and unqualifiable bias in the analysing odontologist are significant limiting factors in bite mark analysis and comparison. The justification for comparing a human bite mark with teeth depends on the mark’s forensic significance which introduces the concept of qualifying criteria.

Human bite marks in skin are complex injuries that commonly demonstrate ambiguous features. A bite mark’s forensic significance is assessed by interpreting the class and individual characteristics of the maxillary and mandibular anterior dentitions represented in scaled photographs of the mark. The unknown variations in the quality and quantity of the causal dentition’s characteristics in bite marks limit the assessment and classification of forensic significance. Currently, there are no scientific data on the weighting of the factors that determine the forensic significance of a human bite mark in skin. The review of the rationale for assessing and classifying forensic significance resulted in a limited empirical classification of forensic significance based on the relative incidence of ambiguous and unambiguous characteristics. Examples of the classification are illustrated in bite marks that demonstrate variations in the class and individual characteristics and in different levels of forensic significance. This review article aims to examine the factors and limited research evidence in the assessment and classification of the forensic significance of human bite marks in skin. The review of an evidence-based rationale for assessing and classifying forensic significance proposes a limited empirical classification that aims to provide reliability in justifying the comparison of a bite mark with teeth.

Factors in Forensic Significance

The forensic significance of a human bite mark in skin indicates the quality and quantity of the class and individual characteristics represented in the bite mark. The interpretation of the characteristics forms the basis for assessing the level of forensic significance.

The class characteristics of human maxillary and mandibular permanent and deciduous anterior dentitions are related to the sizes and shapes of the teeth and arches. The permanent incisors may produce four linear/rectangular marks in the centre of each arc of marks. The mesiodistal crown dimensions of the maxillary and mandibular permanent central and lateral incisors are referenced. The permanent canines may produce either circular, triangular or diamond-shaped marks towards the end of each arc of marks. The adult male and female maxillary and mandibular inter-canine distances are referenced. In cases involving bitten children, it may be necessary to consider the age of the biter by referring to the mesiodistal crown dimensions of the maxillary and mandibular deciduous central, lateral incisors and inter-canine distances and to the first and second transitional periods’ data for the eruption of the maxillary and mandibular permanent central incisors, lateral incisors and canines. The actions of sucking and suckling may produce marks in skin that also constitute class characteristics of human teeth.

The recognition and interpretation of the class characteristics represented in bite mark photographs may support the statement that the mark is of a size and shape that is consistent with a human bite mark. The orientation of the bite mark is possible because the maxillary arch is usually represented by a larger arc composed of larger individual tooth elements. Similarly, the orientation of a single arch representation is based on the arc size and the size and shape of the individual tooth elements. The arch centre point and arch size may be difficult to assess if the arch representation consists of an incomplete arc. The dental arch representation is usually oval or almost circular.

The individual characteristics of human maxillary and mandibular permanent and deciduous anterior dentitions are related to the distinctive features of the incisal edges and cusps of incisors and canines respectively. The incisal edges and cusps may be distinctive due to function, fracture, restorative treatment, caries and developmental abnormality. The cusps of first premolars are rarely recorded. The recognition and interpretation of the individual characteristics represented in bite mark photographs concern the presence or absence, position, rotation and incisal/cuspal detail of each individual tooth element. The positions of adjacent tooth elements may suggest regularity and irregularity within the dental arch. The locations of the mesial and distal incisal angles of incisors suggest their width. The locations of the canines’ cusps limit the inter-canine distances to only be estimated, as arch width was found to be the principal variable in a bite mark. The petechial haemorrhages associated with the interproximal embrasures are a representation of the spacing between adjacent teeth. The absence of an individual element may be false; a non-injured space may indicate either an absent tooth or a deficiency in the incisal/cuspal level. The recognition and interpretation of the individual characteristics represented in bite mark photographs may justify comparing the mark with a specific dentition.

The recognition and interpretation of the injury type and individual characteristics represented in bite mark photographs may enable analysis of the episode of contact between the teeth and skin. Parallel linear marks that are perpendicular to the dental arch are indicative of the biting edges’ characteristics scraping across the skin surface. Palatal and lingual surface characteristics are indicative of tongue pressure on the embouched tissue during suckling. The injury type may be indicative of the degree of causal force when the time of biting and presence of clothing are known.

Assessment of Forensic Significance

The interpretation of the representation of the causal dentition’s characteristics forms the basis for assessing the level of forensic significance of a bite mark in skin. The representation of the class characteristics alone may enable the identification of the mark as a human bite mark. The representation of the class and individual characteristics enable the identification of the mark as a human bite mark and the potential comparison of the mark with the causal dentition. The representation of individual characteristics may vary qualitatively from ambiguous elements to identifiable incisal/cuspal features and quantitatively from single tooth elements to the entire anterior dentition. The presence of distinctive individual characteristics of the incisal/cuspal anatomy are important factors in the assessment of the forensic significance of a bite mark in skin.

The assessment of forensic significance is based on the analysing odontologist’s interpretation of the anterior dentition’s characteristics which is synonymous with the preparation of an unbiased predictor of the causal dentition’s features. The principles of prediction and assessment are based on the interpretation of the class and individual characteristics represented in the scaled photographs of a human bite mark in skin. The preparation of an unbiased predictor supports the assessment of forensic significance. In essence, the degree of prediction and level of forensic significance are directly related as they each reflect the quality, quantity of the causal dentition’s class and individual features. In empirical terms, relatively detailed predictors of the causal dentition’s features relate to high levels of forensic significance; conversely, limited predictors relate to low levels of forensic significance.

In keeping with the preparation of a predictor of the causal dentition’s features, the assessment of forensic significance relies on the analysing odontologist seeing, observing and interpreting the representation of the anterior dentition’s class and individual characteristics in the mark. The terms seeing, observing and interpreting are distinguishable; seeing is a photochemical excitation that produces a neurological experience; observing involves implicit reasoning of knowledge; interpreting involves explicit reasoning of knowledge. Cognitive bias may arise from a variety of sources in expert decision making. The evidence supporting a biased judgement must be sufficient to form the judgement as it cannot be rationalised with irrefutable, contrary evidence; this is precisely why ambiguous stimuli are particularly susceptible to confirmation bias and why many forensic judgements are subject to bias. The risks of cognitive bias in forensic science are lower when results are clear and unambiguous and greater when results are complex, of poor quality and there is an increased reliance on subjective opinion.

Human bite marks in skin invariably demonstrate ambiguous features that render the assessment of forensic significance and preparation of a predictor susceptible to cognitive bias. This is referenced in the human tendency of seeing what one wants to see, inducing odontologists to over-interpret bite marks, especially low forensic significance bite marks. Research in cognitive neuroscience established general principles to manage and limit the sources of cognitive bias in forensic science, including forensic odontology, by firstly examining the crime scene evidence without the biasing power of knowledge of the reference material and contextual information. The completion of an unbiased predictor and the assessment of forensic significance determine whether comparison with teeth is justified or not. This linear sequence of stages ensures that any subsequent comparison is driven by the unbiased interpretation of the bite mark, thereby preventing biased circular reasoning.

In cases of multiple contacts by a single dentition and skin, the resultant bite marks may exhibit significant variations in the type of tissue injury and incidence of identifiable features due to different episodes of contact. The nature of skin and the action of biting create a potentially unique, three-dimensional episode of contact between the teeth and skin. Consequently, a dentition may be represented by varying levels of forensic significance due to different episodes of contact. Therefore, the forensic significance of a bite mark is not necessarily directly related to the distinctive individual characteristics of the incisal/cuspal anatomy of the causal dentition. It is important to note that there are no scientific data on the relationship between a dentition’s individual characteristics and the level of forensic significance of human bite marks in skin.

A variable and unquantifiable degree of primary distortion is intrinsic in human bite marks in skin and consists of tissue and dynamic distortion. Secondary distortion arises after a bite mark is made in skin and may consist of time-related, posture and photographic distortion. Certain anatomical sites are susceptible to significant posture distortion, for example, female breast and limbs. The effects of posture distortion and photographic distortion are limited by the evidence recording odontologist recreating the body position at the time of biting before positioning and holding the rigid, right-angled scale while supervising the photographer. This technique aims to produce optimal scaled photographs of the bite mark. When the body position at the time of biting is unknown and/or the photography is conducted without odontologist supervision or advice, the resultant suboptimal photographs will record an unknown degree of posture distortion and may also record photographic distortion. It is significant that optimal two-dimensional scaled photographs of three-dimensional bite marks in skin are not scientific recordings of the anterior dentition’s class and individual characteristics. The distinctions between optimal and suboptimal photographs are important factors in the assessment of the forensic significance of a bite mark in skin.

Rationale for Assessment and Classification of Forensic Significance

The nature of bite marks in human skin makes experimental research ethically difficult to conduct, consequently, studies mainly used artificial media or animal skin. The dentition that produced test bites in wax was recognised with a high degree of reliability by examiners; however, bite marks in non-vital pig skin demonstrated a much lower degree of reliability. The ability of experienced odontologists to use computer-generated overlays on artificial bite marks in pig skin produced reasonable results, although the intra- and inter-examiner reliability scores were not strong.

The recognition and interpretation of dental characteristics determine whether the degree of correlation between a bite mark and teeth can be determined reliably. A scoring system designed to reflect the forensic significance of a bite mark numerically, demonstrated a high degree of reliability between odontologists and the ability to differentiate between degrees of comparability. Furthermore, if a bite mark was analysed independently with a high level of agreement, this supported the confidence level in the conclusions, echoing previous researchers. Human bite marks in skin are complex injuries that demonstrate considerable variation in the degree and type of tissue injury. The variations in the quality, quantity of the causal dentition’s class and individual characteristics combined with the effects of distortion and cognitive bias limit the assessment and classification of the forensic significance of a bite mark.

A bite mark severity and significance scale aimed to demonstrate the relationship between the severity and forensic significance of a bite mark. The value of Pretty’s standard reference scale in determining forensic significance and in selecting a mark that was amenable to comparison with teeth was noted. Research to evaluate the forensic significance of bite marks by using such a reference scale was also suggested.

A study of 49 bite mark cases, that were part of an appeal hearing, were allocated a forensic significance score; the mean significance scores were evaluated against crime type, experts’ opinion and judicial outcome. The study sample consisted of bite marks with low forensic significance scores, related to the contentious nature of the appeal cases, which introduced a degree of bias in the sample. This metric assessment demonstrated a clear relationship between the level of forensic significance of a bite mark and the experts’ opinion. Marks assessed of low forensic significance were more likely to result in disagreement between experts; conversely, marks of higher forensic significance were more likely to result in agreement. The study provided statistical evidence to support the hypothesis that below a certain level of forensic significance, a bite mark cannot be compared reliably. Furthermore, the bite mark criteria of high forensic significance and minimal distortion were considered essential for reliable bite mark comparison, confirming the view that a level of forensic significance be determined, below which, bite marks should not be compared. This introduced the concept of qualifying criteria that, on completion of feature based analysis, would justify comparing a bite mark with teeth. However, statistical research noted that classified bite mark characteristics on large sections of the population were unavailable and this remains the case for the foreseeable future. The absence of scientific data on the weighting of factors that determine the level of forensic significance of a human bite mark in skin prevents the scientific determination of the level that would justify the comparison of a bite mark with teeth.

In the absence of a scientific classification of forensic significance of bite marks in skin, classification is limited empirically to bite marks that may be compared with teeth due to high quality, quantity class and individual characteristics and bite marks that may not be compared with teeth due to low quality, quantity class and individual characteristics. Inevitably, the boundary between comparison and non-comparison categories is not defined due to variations in the quality, quantity of the causal dentition’s characteristics. Due to the absence of scientific data on the variations in class and individual characteristics, differentiation between the categories is limited to ambiguous and unambiguous representations of the characteristics. The terms ambiguous and unambiguous are relative and may be considered in a spectrum of variations in the quality, quantity of the class and individual characteristics represented in human bite marks in skin. The concept of a spectrum of variations in the characteristics reflects the absence of scientific data that determine the level of forensic significance of bite marks in skin.

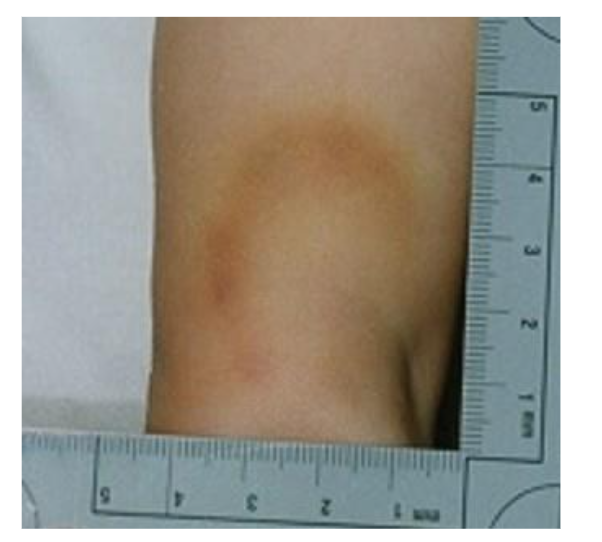

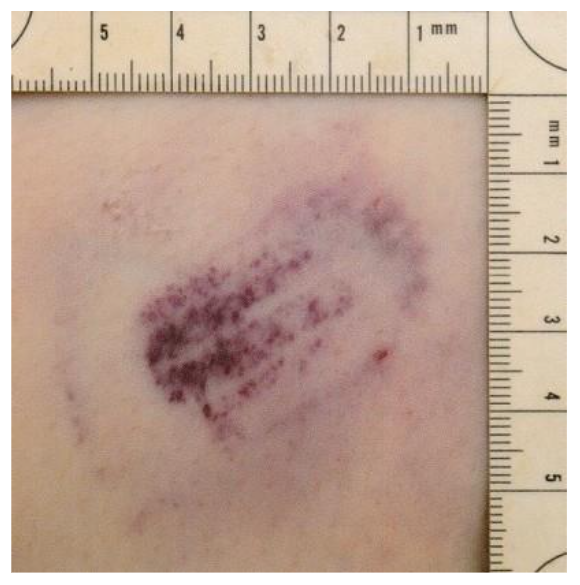

Limited research evidence and empirical observation indicate a conservative, unbiased interpretation of the ambiguous and unambiguous representations of the class and individual characteristics in bite marks in skin. Interpretation is conducted without the biasing power of knowledge of the reference material and contextual information. However, interpretation is limited because ambiguous stimuli are particularly susceptible to confirmation bias and an increased reliance on subjective opinion. Differentiation between the three categories is also limited by the absence of scientific data on the variations in the quality, quantity of the causal dentition’s class and individual characteristics. The rationale for inclusion of the causal dentition’s characteristics in the comparison category may be based on predominantly unambiguous representations of the characteristics as illustrated in Figure 1. By contrast, the rationale for inclusion in the non-comparison category may be based on predominantly ambiguous representations of the characteristics as illustrated in Figure 2. Inclusion in the boundary category may be based on relatively equitable unambiguous and ambiguous representations of the characteristics as illustrated in Figure 3.

Conclusions

The assessment of the forensic significance of human bite marks in skin relies on the interpretation of scaled photographs that are not scientific recordings of the anterior dentition’s class and individual characteristics. Limited research evidence and empirical observation indicate a conservative interpretation of the characteristics represented in a bite mark as the basis for the assessment of forensic significance, which is synonymous with the preparation of an unbiased predictor of the causal dentition’s characteristics. A limited empirical classification of the forensic significance of human bite marks in skin is proposed that is based on the relative incidence of ambiguous and unambiguous representations of the causal dentition’s characteristics. The rationale for the classification may also be applied to conservative conclusions that reflect the limitations of feature based analysis of bite marks and potential comparison with teeth.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

None.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References:

- Sheasby DR. An evidence-based methodology for the analysis and comparison of human bite marks in skin with teeth. Medical Research Archives, 13 (1), 1-15. 2025.

- Sheasby DR. The challenges to the forensic analysis of human bite marks in skin and comparison with teeth. Medical Research Archives, 11 (7.2), 1-13. 2023.

- Pretty IA, Sweet D. A paradigm shift in the analysis of bitemarks. Forensic Science International, 201, 38-44. 2010.

- van der Linden FPGM. Development of the Human Dentition. Quintessence Publishing Company Ltd., London. 2016.

- Bush MA, Bush PJ, Sheets HD. A study of multiple bitemarks inflicted in human skin by a single dentition using geometric morphometric analysis. Forensic Science International, 211, 1-8. 2011.

- Holtkotter H, Sheets HD, Bush PJ, Bush MA. Effect of systematic dental shape modification in bitemarks. Forensic Science International, 228, 61-69. 2013.

- Ström F. Investigation of bite-marks. Journal of Dental Research, 42, 312-316. 1963.

- Keiser-Nielsen S. Forensic odontology – a survey. Presented at the FDI/ERO meeting, Vienna. 1968.

- Nordby JJ. Can we believe what we see, if we see what we believe? – expert disagreement. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 37, 1115-1124. 1992.

- Dror IE. Cognitive and human factors in expert decision making: six fallacies and the eight sources of bias. Analytical Chemistry, 92, 7998-8004. 2020.

- Kassin SM, Dror IE, Kukucka J. The forensic confirmation bias: problems, perspectives and proposed solutions. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 2, 42-52. 2013.

- Forensic Science Regulator. Guidance: Cognitive bias effects relevant to forensic science examinations. FSR-G-217, Issue 2. 2020.

- Clement JG, Blackwell SA. Is current bite mark analysis a misnomer? Forensic Science International, 201, 33-37. 2010.

- Whittaker DK, MacDonald DG. A Colour Atlas of Forensic Dentistry: Bite marks in flesh. Wolfe Medical Publications Ltd., London. 1989.

- Sheasby DR, MacDonald DG. A forensic classification of distortion in human bite marks. Forensic Science International, 122, 75-78. 2001.

- Sheasby DR. Forensic Dentistry – Bite Mark Distortion. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. 1998.

- Bush MA, Miller RG, Bush PJ, Dorion RBJ. Biomechanical factors in human dermal bitemarks in a cadaver model. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 54, 167-176. 2009.

- Whittaker DK. Some laboratory studies on the accuracy of bite mark comparison. International Dental Journal, 25, 166-171. 1975.

- Pretty IA, Sweet D. The scientific basis for human bitemark analyses – a critical review. Science and Justice, 41, 85-92. 2001.

- American Board of Forensic Odontology, Inc. Guidelines for bite mark analysis. Journal of the American Dental Association, 112, 383-386. 1986.

- Rawson RD, Vale GL, Sperber ND, Herschaft EE, Yfantis A. Reliability of the scoring system of the American Board of Forensic Odontology for human bite marks. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 31, 1235-1260. 1986.

- Ligthelm AJ, de Wet FA. Recognition of bite marks: a preliminary report. Journal of Forensic Odontostomatology, 1, 19-26. 1983.

- Pretty IA. Development and validation of a human bitemark severity and significance scale. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 52, 687-691. 2007.

- Avon SL, Victor C, Mayhall JT, Wood RE. Error rates in bite mark analysis in an in vivo animal model. Forensic Science International, 201, 45-55. 2010.

- Bowers CM, Pretty IA. Expert disagreement in bitemark casework. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 54, 915-918. 2009.

- Aitken C, MacDonald DG. An application of discrete kernel methods to forensic odontology. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 28, 55-61. 1979.

- Miller RG, Bush PJ, Dorion RBJ, Bush MA. Uniqueness of the dentition as impressed in human skin: a cadaver model. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 54, 909-914. 2009.