Effectiveness of Telebehavioral vs In-Person Counseling

A Quasi-Experiment to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Telebehavioral versus In-Person Counseling in Rural Texas

Whitney R. Garney¹,², Trey W. Armstrong¹, Carly E. McCord¹, Krystal T. Simmons³, Mandy Spadine Wolever³, Kristen M. Garcia¹, Emma McWhorter¹*

- Telehealth Institute, Texas A&M Health, College Station, Texas

- School of Public Health, Texas A&M Health, College Station, Texas

- College of Education and Human Development, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED 31 December 2025

CITATION Garney, WR., Armstrong, TW., et al., 2025. A Quasi-Experiment to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Telebehavioral versus In-Person Counseling in Rural Texas. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(12). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i12.7170

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i12.7170

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Rural residents experience mental health disparities when compared to urban communities due to complex factors. Telehealth is one way to bridge the gap, but existing research on telebehavioral health effectiveness is sparse for rural communities, especially when comparing telehealth to in-person services.

Methods: To investigate if telebehavioral health outcomes were similar to traditional in-person counseling, evaluators designed a quasi-experiment to detect differences in behavioral health outcomes between a group of rural residents who received services via video conference or telephone and a second group who received in-person services.

Results: Regarding depression outcomes, PHQ9 scores were higher than the clinical level at baseline (in-person: 11.39, telehealth: 13.22) and decreased over time. Scores for the in-person group, on average, fell below clinical level at 8 weeks and telehealth groups scores, on average fell below clinical level at 12 weeks. Similarly, regarding anxiety outcomes, both groups started above the clinical level for GAD7 scores at baseline (in-person: 10.00, telehealth: 12.34). On average, scores for the in-person group dropped below the clinical level at 4 weeks while scores for the telehealth group, on average, dropped below the clinical level at 8 weeks or later.

Discussion: This study provides evidence in support of telebehavioral health services, specifically in reference to depression and anxiety concerns. Both telehealth and in-person groups showed improvement in terms of having positive rates of overall improvement, low occurrence of reliable deterioration, and a growth model showing scores starting above the clinical level and falling across treatment. This study supports the conclusion that telebehavioral health services can be reliably used to treat depression and anxiety, similar to in-person care.

Keywords: behavioral health, telehealth, quantitative analysis, service modality.

Introduction

Rural residents experience mental health disparities in outcomes and access when compared to urban communities. While both geographies have similar rates of mental health disorders, rural residents often seek treatment later, which can lead to more severe illness and increased costs. The root causes of mental health disparities are complex and interconnected; however, it is well established that limited access and availability of local specialty services contribute to lack of treatment. Across the United States, more than 90% of psychologists and psychiatrists solely practice in urbanized areas, which has led to rural communities making up approximately 62% of all Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas. In Texas, only one third (approximately 32%) of the need for mental health providers is met. Due to this shortage, rural residents often encounter waitlists with extensive delays to receive treatment, as well as increased costs and burden due to travel and taking time off work. Seeking services outside of one’s community also decreases the social support available to the patient as individuals are further from friends and family.

Telebehavioral counseling creates a bridge of accessibility to many in underserved, rural areas. For the purpose of this article, telebehavioral counseling is defined as counseling delivered via videoconferencing or telephone modalities. Providers can use telebehavioral counseling to treat clients in their own homes or in local sites in their communities. Financial concerns related to transportation availability, gas, childcare, and time off of work are mitigated, and existing literature suggests that by increasing access to providers, individuals may seek treatment sooner. Telebehavioral counseling can also bridge gaps in affirmative treatment for marginalized community members.

Stigma in rural communities also acts as a barrier when providing mental health services. Due to social norms, it is common for individuals to feel embarrassed and/or associate negative emotions with seeking mental health treatment. These concerns can be heightened when individuals know the individuals they must interact with while in pursuit of mental health services. Telebehavioral counseling combats stigma-related barriers by allowing individuals to seek care from the comfort and privacy of their home or even in their car while on a lunch break.

Existing meta-analyses have shown that telebehavioral counseling has similar symptom reduction compared to those who received counseling in-person, and improvements are maintained at both three- and six-month follow-up. Research indicates that telehealth is effective at treating depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic symptoms across the lifespan. Some research has shown that telebehavioral counseling has higher rates of treatment completion, compared to other modalities. Treatment as usual (TAU) studies often utilize methodologies to assess effectiveness focusing on rates of change, dose-response relationships, and cost effectiveness analysis. Psychotherapy TAU studies include clients who have not been randomized into a controlled trial; rather, they are accessing healthcare services (initiating or continuing) as someone usually would. Standard care data can capture more diverse and underrepresented populations, who historically may not have been represented well in research, including rural-residing clients. TAU studies have produced similar results to RCTs when treating depression.

Despite positive outcomes, further research is needed to explore the impact of telebehavioral health interventions on special populations and unique geographies. Quality telehealth research has traditionally been conducted in urban and suburban settings, which is not necessarily generalizable to rural areas. Significant barriers to conducting rigorous research, such as randomized experimental trials, in rural areas exist due to small sample sizes and contextual differences between communities, which can negatively impact control data. The purpose of this study is to address gaps in existing research and report the findings of a quasi-experiment conducted in rural Texas communities to demonstrate the effectiveness of telebehavioral health treatment, when compared to in-person treatment.

Methods

This study was led by the Texas A&M Telebehavioral Care Program (TBC; now the Texas A&M Health Telehealth Institute) as part of a project funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to provide telebehavioral counseling services to rural and underserved populations residing in the Brazos Valley region of Texas using a “hub-and-spoke” model. The Telebehavioral Care Program functioned as the primary location (the “hub”) for counselors to host video conference counseling sessions with their patients, and five rural spoke sites served as a local access point for patients to access telebehavioral health services via a secure, reliable broadband internet connection. All counselors were doctoral-level psychology (Clinical Psychology, Counseling Psychology, School Psychology) students providing care under the supervision of licensed psychologists.

STUDY DESIGN

To investigate if telebehavioral health outcomes were similar to traditional in-person counseling, evaluators used a quasi-experimental approach to investigate differences in behavioral health outcomes between a group of rural residents who received services via video conference (and telephone if video conference was not possible) and a second group who received in-person services. The study was designed to identify differences in anxiety and depression levels between counseling services offered in-person and via telehealth at intake and four (+/-2) weeks, eight (+/-2) weeks, and 12 (+/-2) weeks.

Counseling effectiveness for the two groups was evaluated using a similar framework found in McCord et al. Pulling from the Clinically Significant Change framework by Jacobson & Truax as used in Armstrong et al., this study looked at overall improvement (OI) and reliable deterioration (RD) in the in-person group and the telehealth group. Overall improvement was defined as improving by at least the reliable change index (RCI) on the outcome measure on any subsequent measurement when compared to the intake score. Reliable deterioration refers to an increase in the RCI on the outcome measure. This provides comparisons of the initial intake session to subsequent session scores. Latent growth curves were also fitted to estimate session-to-session improvement trajectories. The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 often have a clinical level of 10 points (e.g., Gilbody et al.). A score > 9 indicates the probable diagnosis of depression/anxiety, and a score < 10 points indicates mild symptomology or no likely diagnosis. This is also called creating a clinical range and non-clinical range.

PARTICIPANTS

The study was approved by the Texas A&M University Institutional Review Board. The samples used for this study were selected based on demographic similarities and convenience. Participants came from two clinics that serve rural residents in the Brazos Valley, Texas. Clients are often low-income and under-insured. Both clinics are training clinics, whose counseling services are provided by doctoral-level psychology students (Clinical Psychology, Counseling Psychology, School Psychology) under the supervision of Licensed Psychologists.

Treatment Group: Telebehavioral Counseling

Telebehavioral services were offered to individuals, 18 years and older, located in the five rural spoke locations. Clients were able to go to a spoke site in their community to connect with counselors at the hub site, take the videoconference session from their home, or other private location of their convenience. Client information was collected from intake and throughout counseling. For this evaluation, retrospective data was used for clients that completed an intake resulting in a sample of 82 clients.

Comparison Group: In-Person Counseling

The in-person comparison group came from a training clinic that provided traditional in-person counseling to clients. As a part of the project data collection, adult clients who enrolled at this clinic for services were also tracked from intake throughout counseling. Similar to the telebehavioral counseling group, retrospective data was used for clients that fully completed the intake resulting in a sample of 42 clients.

MEASURES

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

The Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item (PHQ-9) was used to diagnose, then monitor the severity of depression and client response to treatment. The PHQ-9 was self-administered by the client and asks questions such as “Over the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? Little interest or pleasure in doing things?”. The PHQ-9 scores range from 0 to 27 with each of the nine items being scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Additionally, depression severity can be classified into five categories: None (0-4), Mild (5-9), Moderate (10-14), Moderately Severe(15-19), and Severe (20-27). An RCI of 5 points will be used.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) was used for screening and assessing severity of generalized anxiety disorder. The GAD-7 was also self-administered. The questionnaire asks questions such as “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge?”. Scores for each response range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) with possible scores from 0 to 21. There are also cut-off points for anxiety severity classification including: Minimal (0-4), Mild (5-9), Moderate (10-14), and Severe (greater than 15). An RCI of 5 points will be used.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Demographic information including age, race, ethnicity, and sex was obtained for each participant. Relevant clinical data were obtained from intake forms, clinical assessments, and review of client files. Descriptive statistics of the sample are provided. To determine whether an “event” (i.e., Overall Improvement, Reliable Deterioration) occurred, subsequent PHQ-9/GAD-7 scores were subtracted from the client’s intake PHQ-9/GAD-7 score. Latent growth curve analyses (LGCA) were used to compare growth across time between the two groups (i.e., session-to-session score improvement). Analyses were conducted using Stata 14.1. Survival analyses were fitted with the Kaplan-Meier estimator. The LGCA models used the Maximum Likelihood Mean and Variance Adjusted (MLMV) estimator. LGCA model fit will be evaluated by Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI).

Results

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS AND GROUP COMPARISONS

The sample consisted of 124 clients, 82 clients in the treatment telehealth group and 42 in the in-person comparison group. A majority of the clients identified as female (80.65%), and White Non-Hispanic (56.10%). See Table 1 for additional demographic information. The telehealth group was on average older (M = 41.84, SD = 15.36) than the in-person group (M = 29.69, SD = 8.0; t(122) = -4.80, p < .001). The groups did not differ in terms of race, ethnicity, or sex. At intake, both groups’ PHQ-9 and GAD-7 mean scores fell in the clinical range (i.e., were categorized as moderate depression/anxiety or higher).

| Variable | Telebehavioral Health Group (n=82) | In-Person Control Group (n=42) | All (N=124) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 41.84 (15.36) | 29.69 (8) | 37.73 (14.49) |

| Sex, (% of group) | Male: 15 (18.29) Female: 67 (81.71) Other: 0 (0) |

Male: 8 (19.05) Female: 33 (78.57) Other: 1 (2.38) |

Male: 23 (18.54) Female: 100 (80.65) Other: 1 (0.80) |

| Race/Ethnicity, (% of group) | White, Non-Hispanic: 49 (59.76) White, Hispanic: 13 (15.85) White, Unknown: 4 (4.88) Black, Non-Hispanic: 9 (10.98) Black, Hispanic: 2 (2.44) Black, Unknown: 2 (2.44) Asian: 0 (0) American Indian/Alaska Native: 1 (1.22) Multiracial: 1 (1.22) Unknown: 1 (1.22) |

White, Non-Hispanic: 20 (47.62) White, Hispanic: 8 (19.05) White, Unknown: 7 (16.67) Black, Non-Hispanic: 2 (4.76) Black, Hispanic: 0 (0) Black, Unknown: 1 (2.38) Asian: 2 (4.76) American Indian/Alaska Native: 0 (0) Multiracial: 2 (4.76) Unknown: 0 (0) |

White, Non-Hispanic: 69 (56.10) White, Hispanic: 21 (17.07) White, Unknown: 11 (8.94) Black, Non-Hispanic: 11 (8.94) Black, Hispanic: 2 (1.63) Black, Unknown: 3 (2.44) Asian: 2 (1.63) American Indian/Alaska Native: 1 (0.81) Multiracial: 3 (2.44) Unknown: 1 (0.81) |

a. The telebehavioral health group had an average older age.

b. Sex and race/ethnicity were not significantly different.

DEPRESSION OUTCOMES

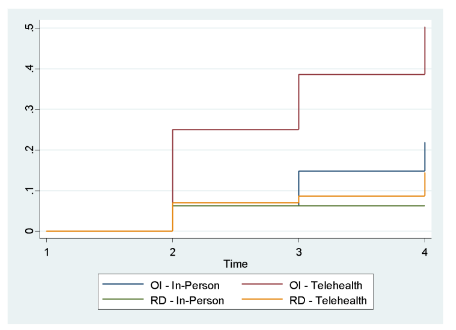

In the in-person group, 10 clients only completed an intake. Of the remaining 32 clients, 5 (15.63%) clients achieved overall improvement by 12 weeks. The telehealth group had 10 clients only complete an intake. Of the 72 clients, 30 (41.67%) clients achieved overall improvement. A log-rank test showed this difference in outcomes was statistically significant, Χ2(1, N = 35) = 6.21, p = .013) with the telehealth group having more events occur than expected. In the in-person comparison group, 2 (6.25%) clients reached reliable deterioration by 12 weeks, and the telehealth group had 8 (11.11%) clients. A log-rank test was not statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier event probability curves for OI and RD for the in-person and telehealth groups are depicted in Figure 1.

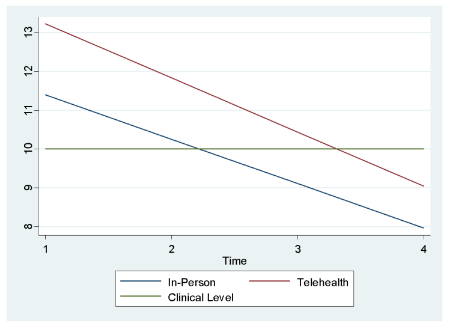

To compare PHQ-9 scores between groups across their treatment, a multiple-groups latent growth curve model was fitted. Model fit was adequate, RMSEA = .086, CFI = .97, TLI = .98, and the model’s coefficient of determination was .97. Both groups started higher than the clinical level (in-person: 11.39; telehealth: 13.22) and had a steady decline of scores across time (in-person: -1.14; telehealth: -1.39). Scores, on average, fall below the clinical level by 8 weeks for the in-person group and 12 weeks for the telehealth group. The variance for the intercepts was larger (in-person: 41.14; telehealth: 33.07) than the variances for the linear slopes (in-person: 1.16; telehealth: 2.20). The covariance (-3.95) in the in-person group showed some tendency for high starting scores to have a steeper decline over time. The covariance (.89) in the telehealth group was smaller. The model results are displayed in Figure 2.

ANXIETY OUTCOMES

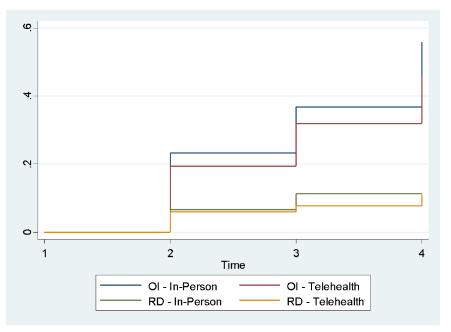

In the in-person group, 12 clients only completed an intake. Of the remaining 30, 13 (43.33%) clients achieved overall improvement by 12 weeks. The telehealth group had 15 clients that only completed an intake. Of the remaining 67, 24 (35.82%) clients achieved overall improvement by 12 weeks. A log-rank test was not statistically significant. In the in-person group, 3 (10%) clients reached reliable deterioration by 12 weeks, and the telehealth group had 6 (8.96%) clients. A log-rank test was not statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier event probability curves for OI and RD between the two groups are depicted in Figure 3.

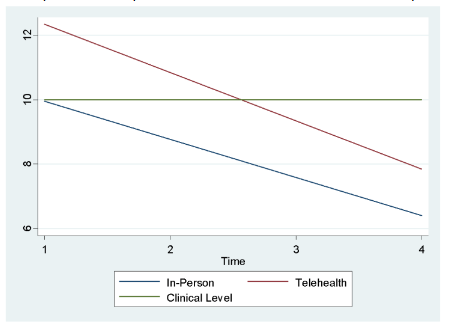

To compare GAD-7 scores between groups across their treatment, another multiple-groups latent growth curve model was fitted. Model fit was good, RMSEA = .075, CFI = .96, TLI = 97, and the model’s coefficient of determination was .91. Both groups started higher than the clinical level (in-person: 10.00; telehealth: 12.34) and had a steady decline of scores across time (in-person: -1.19; telehealth: -1.50). The in-person group started on the clinical level and dropped below at 4 weeks. The telehealth group had a 3-point decrease on average at 8 weeks and after. The variance for the intercepts was larger (in-person: 27.49; telehealth: 24.11) than the variances for the linear slopes (in-person: .16; telehealth: .61). A similar pattern was observed with the covariance (-2.75) in the in-person group suggesting some tendency for high starting scores to have a steeper decline over time. The covariance (1.25) in the telehealth group was smaller. GAD-7 model results are presented in Figure 4.

Discussion

This study provided an examination of telebehavioral counseling compared to in-person counseling services in the Brazos Valley, Texas. Both groups showed improvement in terms of having positive rates of overall improvement (OI), low occurrence of reliable deterioration (RD), and a growth model showing scores starting above the clinical level and falling across treatment. By 12 weeks, average scores for depression in anxiety in both groups were below the clinical threshold. A larger study the HRSA Evidence-Based Telehealth Network Program (EB-TNP) reported similar outcomes were seen across the multi-state program. This study contributes to the existing literature as it uses an alternative statistical approach to provide additional evidence that telebehavioral counseling and in-person counseling outcomes were comparable in the rural Brazos Valley region. Additionally, this study provides support for reliable improvement achieved by doctoral student clinicians regardless of service-delivery modality.

Given the dramatic shifts in telehealth and telebehavioral health utilization driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, this study has important policy-level implications. Pre-pandemic, roughly 29% of mental health agencies offered telehealth as an option to patients. During the pandemic, provider and patient adoption increased. Post pandemic, a long-term increase in utilization of telebehavioral has been expected due to increased acceptance and increased need for mental health services.

This study provides additional support for using telebehavioral health services to treat depression and anxiety and may offer useful guidance for the evolving telehealth policy landscape. Several pandemic-era flexibilities granted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expired on September 30, 2025, resulting in the return of in-person visit requirements for behavioral health and the reinstatement of originating site and geographic restrictions for primary care. Although these flexibilities were reinstated in November 2025, the extension lasts only through January 2026. Without permanent legislative action, this ongoing “regulatory whiplash” undermines organizations’ confidence in adopting or sustaining telehealth services. At the same time, payment parity remains inconsistent across states, and the combination of modality mandates (e.g., in-person requirements, limitations on audio-only services) and unequal reimbursement poses substantial risks to access—particularly for rural and underserved populations. By enabling clinicians in urban areas to provide remote care, telebehavioral health offers rural residents accessible treatment options and helps mitigate the challenges associated with Mental Health Professional Shortage Area.

LIMITATIONS

As with all research studies, this project has limitations. One major limitation is that during the study duration, the clinics had to lockdown due to requirements of the COVID-19 pandemic. This history effect led to smaller group sizes than anticipated, particularly the in-person group. The limited measurements dictated by the study protocol did not allow the analyses to show as much detail across many sessions compared to other studies. The multiple-groups LGCA models should be considered tentative as these models are often run with a larger sample size. Future studies could explore the use of cluster randomized control trials to further evaluate the effectiveness of telebehavioral health services. Lastly, the clinicians used in this study were doctoral-level psychology students under the supervision of a licensed psychologist. While the authors believe this is an innovative method to expand access and the findings from this study point to the promise of clinicians in training using telehealth, the results may not be generalizable to all clinic settings.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence in support of telebehavioral health services, specifically in reference to depression and anxiety concerns. Both telehealth and in-person groups showed improvement in terms of having positive rates of overall improvement, low occurrence of reliable deterioration, and a growth model showing scores starting above the clinical level and falling across treatment. By 12 weeks, both groups on average were below the clinical level. This was observed for both depression and anxiety outcome scores. Given that our study shows comparable outcomes for telebehavioral and in-person care in this rural context, preserving modality choice, payment equity, and remote access is essential to ensure location does not determine care quality or access.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) [Grant number: G01RH32158] as part of an award totaling $974,767. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References:

- Schroeder S, Roberts H, Heitkamp T, Clarke B, Gotham HJ, Franta E. Rural mental health care during a global health pandemic: Addressing and supporting the rapid transition to tele-mental health. Journal of Rural Mental Health. 2021;45(1):1-13. doi:10.1037/rmh0000169

- Wilson W, Bangs A, Hatting T. Future of Rural Behavioral Health. NRHA Policy Papers [online]. Published online 2015. Accessed July 31, 2025. https://www.ruralhealth.us/getmedia/01d32ac2-da4c-45a7-b4d8-368accbd6682/The-Future-of-Rural-Behavioral-Health_Feb-2015.pdf

- Myers CR. Using Telehealth to Remediate Rural Mental Health and Healthcare Disparities. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2019;40(3):233-239. doi:10.1080/01612840.2018.1499157

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Designated health professional shortage areas statistics: First quarter of fiscal year 2022 designated HPSA quarterly summary. Published online 2022.

- Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, Johnston B, Callahan EJ, Yellowlees PM. The Effectiveness of Telemental Health: A 2013 Review. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2013;19(6):444-454. doi:10.1089/tmj.2013.0075

- Madigan S, Racine N, Cooke JE, Korczak DJ. COVID-19 and telemental health: Benefits, challenges, and future directions. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne. 2021;62(1):5-11. doi:10.1037/cap0000259

- Ralston AL, Holt NR, Hope DA. Tele-mental health with marginalized communities in rural locales: Trainee and supervisor perspectives. Journal of Rural Mental Health. 2020;44(4):268-273. doi:10.1037/rmh0000142

- Costa M, Reis G, Pavlo A, Bellamy C, Ponte K, Davidson L. Tele-Mental Health Utilization Among People with Mental Illness to Access Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(4):720-726. doi:10.1007/s10597-021-00789-7

- Norwood C, Moghaddam NG, Malins S, Sabin‐Farrell R. Working alliance and outcome effectiveness in videoconferencing psychotherapy: A systematic review and noninferiority meta‐analysis. Clin Psychology and Psychoth. 2018;25(6):797-808. doi:10.1002/cpp.2315

- Lin T, Heckman TG, Anderson T. The efficacy of synchronous teletherapy versus in-person therapy: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2022;29(2):167-178. doi:10.1037/cps0000056

- Lamb T, Pachana NA, Dissanayaka N. Update of Recent Literature on Remotely Delivered Psychotherapy Interventions for Anxiety and Depression. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2019;25(8):671-677. doi:10.1089/tmj.2018.0079

- Tuerk PW, Keller SM, Acierno R. Treatment for Anxiety and Depression via Clinical Videoconferencing: Evidence Base and Barriers to Expanded Access in Practice. FOC. 2018;16(4):363-369. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20180027

- Acierno R, Gros DF, Ruggiero KJ, et al. BEHAVIORAL ACTIVATION AND THERAPEUTIC EXPOSURE FOR POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER: A NONINFERIORITY TRIAL OF TREATMENT DELIVERED IN PERSON VERSUS HOME-BASED TELEHEALTH: Research Article: BATE Telehealth. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(5):415-423. doi:10.1002/da.22476

- Knowlton CN, Nelson KG. PTSD telehealth treatments for veterans: Comparing outcomes from in-person, clinic-to-clinic, and home-based telehealth therapies. Journal of Rural Mental Health. 2021;45(4):243-255. doi:10.1037/rmh0000190

- Luxton DD, Pruitt LD, Wagner A, Smolenski DJ, Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, Gahm G. Home-based telebehavioral health for U.S. military personnel and veterans with depression: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016;84(11):923-934. doi:10.1037/ccp0000135

- Morland LA, Mackintosh MA, Rosen CS, et al. TELEMEDICINE VERSUS IN-PERSON DELIVERY OF COGNITIVE PROCESSING THERAPY FOR WOMEN WITH POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER: A RANDOMIZED NONINFERIORITY TRIAL: Research Article: Telemental Health for Women with PTSD. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(11):811-820. doi:10.1002/da.22397

- Yuen EK, Gros DF, Price M, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Home‐Based Telehealth Versus In‐Person Prolonged Exposure for Combat‐Related PTSD in Veterans: Preliminary Results. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71(6):500-512. doi:10.1002/jclp.22168

- Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Munder T, Heer S, Wampold BE. Enduring effects of evidence-based psychotherapies in acute depression and anxiety disorders versus treatment as usual at follow-up — A longitudinal meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34(5):367-375. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2014.05.001

- Laidlaw K, Davidson K, Toner H, et al. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy vs treatment as usual in the treatment of mild to moderate late life depression. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2008;23(8):843-850. doi:10.1002/gps.1993

- Wampold BE, Budge SL, Laska KM, et al. Evidence-based treatments for depression and anxiety versus treatment-as-usual: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(8):1304-1312. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.012

- Alegría M, Ludman E, Kafali EN, et al. Effectiveness of the Engagement and Counseling for Latinos (ECLA) Intervention in Low-income Latinos. Medical Care. 2014;52(11):989-997. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000232

- Khatri N, Marziali E, Tchernikov I, Sheppard N. Comparing telehealth-based and clinic-based group cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with depression and anxiety: a pilot study. CIA. Published online May 2014:765. doi:10.2147/CIA.S57832

- Stubbings DR, Rees CS, Roberts LD, Kane RT. Comparing In-Person to Videoconference-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Mood and Anxiety Disorders: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(11):e258. doi:10.2196/jmir.2564

- Griffiths L, Blignault I, Yellowlees P. Telemedicine as a means of delivering cognitive-behavioural therapy to rural and remote mental health clients. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(3):136-140. doi:10.1258/135763306776738567

- McCord CE, Saenz JJ, Armstrong TW, Elliott TR. Training the next generation of counseling psychologists in the practice of telepsychology. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2015;28(3):324-344. doi:10.1080/09515070.2015.1053433

- Garney WR, McCord CE, Walsh MV, Alaniz AB. Using an Interactive Systems Framework to Expand Telepsychology Innovations in Underserved Communities. Scientifica. 2016;2016:1-8. doi:10.1155/2016/4818053

- McCord CE, Console K, Jackson K, et al. Telepsychology training in a public health crisis: a case example. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2021;34(3-4):608-623. doi:10.1080/09515070.2020.1782842

- McCord C, Ullrich F, Merchant KAS, et al. Comparison of in-person vs. telebehavioral health outcomes from rural populations across America. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):778. doi:10.1186/s12888-022-04421-0

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(1):12-19. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12

- Armstrong TW, McCord CE, Stickley MM, George N, Elliott TR. Assessing depression outcomes in teletherapy for underserved residents in Central Texas: Telehealth’s move to treatment-as-usual. Journal of Rural Mental Health. 2022;46(4):225-236. doi:10.1037/rmh0000215

- Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for Depression in Medical Settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): A Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. J GEN INTERN MED. 2007;22(11):1596-1602. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Molfenter T, Heitkamp T, Murphy AA, Tapscott S, Behlman S, Cody OJ. Use of Telehealth in Mental Health (MH) Services During and After COVID-19. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(7):1244-1251. doi:10.1007/s10597-021-00861-2

- Mulvaney-Day N, Dean D, Miller K, Camacho-Cook J. Trends in Use of Telehealth for Behavioral Health Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Considerations for Payers and Employers. Am J Health Promot. 2022;36(7):1237-1241. doi:10.1177/08901171221112488e

- The Telehealth Policy Cliff: Preparing for October 1, 2025. National Consortium of Telehealth Resource Centers. September 26, 2025. https://telehealthresourcecenter.org/resources/the-telehealth-policy-cliff-preparing-for-october-1-2025/

- Parity: Policy Look up. Center for Connected Health Policy. National Telehealth Policy Resource Center. https://www.cchpca.org/topic/parity/