Advancements in Evaluating Coronary Microvasculature

Advancements in the Invasive Evaluation of Coronary Microvasculature in Acute Myocardial Infarction

Juan Arango ¹, Victor Cazac ², Nadejda Cazac ², Stuart Zarich ¹

¹ Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale New Haven Health, Bridgeport Hospital, CT, USA.

² Department of Internal Medicine, Norwalk Hospital, Nuvance Health, CT, USA

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 August 2025

CITATION: Zarich, S., 2025. Advancements in the Invasive Evaluation of Coronary Microvasculature in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6756

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6756

ISSN: 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Coronary microvascular dysfunction represents a critical yet historically under-recognized contributor to adverse outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. As contemporary revascularization strategies continue to reduce epicardial artery-related mortality, the limitations imposed by impaired microvascular perfusion have become increasingly evident. Microvascular obstruction, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and endothelial dysfunction all contribute to suboptimal myocardial recovery, despite successful epicardial intervention.

Invasive methods of assessing intravascular hemodynamics have been previously described, with identification of multiple caveats in their interpretation. Although there are multiple physiological parameters describing epicardial blood flow, coronary microvasculature evaluation has been historically limited to only a few indicators, such as coronary flow reserve and the index of microvascular resistance. Moreover, their role in the evaluation of patients remains uncertain in the case of acute coronary syndromes.

This review highlights the growing armamentarium of invasive and non-invasive techniques now available to characterize the coronary microvascular function with greater precision, with a focus on their role in acute myocardial infarction.

Keywords

coronary microvascular dysfunction, acute myocardial infarction, invasive evaluation, coronary flow reserve, index of microvascular resistance

1. Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI), continues to be a significant global health concern, contributing substantially to morbidity and mortality rates worldwide. The advent of reperfusion strategies, particularly primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI), has markedly improved patient outcomes by restoring blood flow in the obstructed epicardial coronary arteries. However, despite successful revascularization at the epicardial level, a subset of patients continues to experience adverse outcomes. This paradox has directed clinical and research attention toward the coronary microvasculature the network of tiny blood vessels responsible for delivering oxygen and nutrients directly to the heart muscle.

Microvascular dysfunction, particularly microvascular obstruction (MVO), has emerged as a pivotal factor influencing post-AMI recovery. MVO refers to the impairment of blood flow at the microvascular level despite the reopening of larger coronary arteries. This condition is closely associated with larger infarct sizes, adverse left ventricular remodeling, and diminished functional recovery, ultimately leading to poorer clinical outcomes. Recognizing the critical role of the microvasculature in AMI has spurred the development and refinement of invasive assessment techniques aimed at evaluating microvascular function more accurately.

This review endeavors to synthesize recent advancements in the invasive assessment of coronary microvascular function in patients who have suffered an AMI, with a particular focus on studies published since January 2020. By exploring the latest diagnostic tools and methodologies, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of how these innovations can enhance patient risk stratification, inform therapeutic decisions, and ultimately improve clinical outcomes in the context of AMI.

2. Methods

A systematic literature search was done of PubMed and the Cochrane databases for English-language studies published between January 2020 and February 2025. Studies of interest included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, systematic reviews and observational studies. Search categories included combinations of fractional flow reserve, coronary flow reserve, the index of microcirculatory resistance and STEMI (see Table 1 for full list of search terms). Additionally, the references of selected review articles, meta-analyses and guideline statements were reviewed. Selected articles were agreed upon by all authors.

| Attempts | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| 1 | fractional flow reserve |

| 2 | coronary flow reserve |

| 3 | index of microcirculatory resistance |

| 4 | fractional flow reserve, myocardial infarction [MeSH Terms] |

| 5 | fractional flow reserve, STEMI [MeSH Terms] |

| 6 | fractional flow reserve, acute coronary syndrome [MeSH Terms] |

| 7 | coronary flow reserve, STEMI [MeSH Terms] |

| 8 | cardioprotection |

| 9 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 8 |

3. Pathophysiology of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Acute Myocardial Infarction

The coronary microcirculation consists of arterioles and capillaries that play a crucial role in regulating myocardial blood flow and ensuring adequate oxygen delivery to heart tissues. In the event of an AMI, several mechanisms can lead to microvascular dysfunction:

- Microvascular Obstruction (MVO): Following primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI), the embolization of atherothrombotic debris and endothelial injury can result in MVO. In this scenario, even though the epicardial arteries are successfully reopened, perfusion at the microvascular level remains compromised. This phenomenon is linked to larger infarct sizes and poorer functional recovery.

- Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: The restoration of blood flow, while essential, can paradoxically inflict additional myocardial damage. This injury occurs through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and calcium overload, all of which further undermine microvascular integrity.

- Endothelial Dysfunction: Endothelial cells are integral to maintaining vascular tone and homeostasis. Post-AMI, endothelial dysfunction can worsen microvascular impairment, leading to inadequate vasodilation and an increased propensity for thrombosis.

A thorough understanding of these pathophysiological processes is vital for developing targeted therapies aimed at preserving or restoring microvascular function in AMI patients.

4. Established and Emerging Invasive Assessment Methods

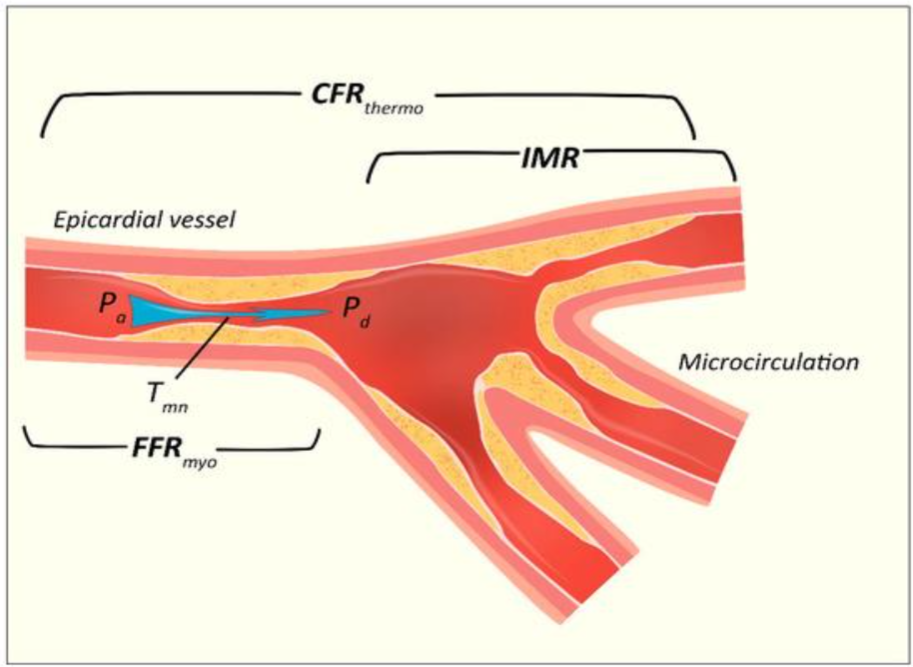

Accurate evaluation of the coronary microvasculature is essential for effective risk stratification and guiding therapeutic interventions in AMI patients. Several invasive techniques have been developed and refined to assess microvascular function (figure 1).

4.1. CORONARY FLOW RESERVE

Coronary Flow Reserve (CFR) is a critical parameter that quantifies the capacity of coronary circulation to augment blood flow in response to increased myocardial demand. It was initially validated in 2001 by de Bruyne and colleagues, who used a thermodilution model to measure CFR via a pressure monitoring wire. Using the law of thermodilution, flow (F) can be calculated using the ratio between V (vascular volume travelling from injection site to sensor) and Tmn (mean transit time of an indicator, such as saline, from injection site to sensor), as follows:

F = V / Tmn

It is calculated as the ratio of maximal hyperemic blood flow to resting flow, integrating the function of both epicardial arteries and the microvasculature.

CFR = (F at hyperemia) / (F at rest) = (V / Tmn) at hyperemia / (V / Tmn) at rest

Furthermore, assuming that epicardial volume remains unchanged, CFR can be calculated as follows:

CFR = (Tmn at hyperemia) / (Tmn at rest)

Unfortunately, the latter is one of the disadvantages of CFR, as epicardial blood flow may be subject to flow-induced endothelium mediated vasodilation during the hyperemic phase. In turn, this would lead to an overestimation of the actual CFR. Ideally, one would determine in a simultaneous fashion both the cross-sectional area of the vessel and the mean velocity to calculate the coronary flow. The average peak velocity (APV) can be measured directly with the use of Doppler-based wire systems. Furthermore, a coefficient of 0.5 is used to derive the mean coronary flow, and subsequently a coronary flow velocity reserve (CFVR), as follows:

CFVR = (F at hyperemia) / (F at rest) = (0.5 × APV at hyperemia) / (0.5 × APV at rest) = (APV at hyperemia) / (APV at rest)

However, the use of 0.5 coefficient is not able to accurately derive true flow parameters based on APV. Although CFR calculation using Doppler derived average peak velocity have shown strong correlation with Positron Emission Tomography (PET)-CFR, the quality of Doppler flow velocity was found to be significantly poorer than in thermodilution, with higher interobserver variability. For example, in a study performed by Everaars et al, 14% of the studies had to be excluded due to poor quality of Doppler tracings. Thus, it appears that thermodilution derived CFR is a more technically feasible method.

A CFR value less than 2.0 is generally indicative of impaired coronary microvascular function, suggesting the presence of coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD).

In the context of Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI), the assessment of CFR is complex. The acute ischemic event can lead to myocardial stunning and alterations in hemodynamics, which may transiently affect microvascular function and, consequently, CFR measurements. Therefore, CFR values obtained during the acute phase of AMI might not accurately reflect the patient’s baseline coronary microvascular function. It is advisable to perform CFR assessments after the acute phase has resolved to obtain more reliable and representative measurements.

Other limitations of CFR are the fact that it is affected by overall hemodynamics and assumes negligible contribution from collateral flow. Moreover, while CFR provides valuable insights into the coronary circulation’s ability to increase blood flow, it does not distinguish between epicardial and microvascular contributions to flow limitation. To address this limitation, additional indices such as the Index of Microcirculatory Resistance (IMR) can be employed.

4.2 FRACTIONAL FLOW RESERVE

FFR, calculated as the ratio between mean distal coronary pressure (Pd) and mean arterial pressure (Pa), considers both epicardial and collateral blood flow an advantage over CFR. However, for a relationship between pressure and flow to be valid, the resistance in the circuit (coronary vessel) would have to be constant and minimal. The latter can be achieved with maximal hyperemia, when a direct linear relationship exists between flow and inverse of flow velocity (1/Tmn). CFR can be used in conjunction with fractional flow reserve (FFR) to assess both plaque burden and microvascular dysfunction. Nonetheless, although FFR is not affected by overall hemodynamics, it assumes normal microvasculature and does not reflect microvascular dysfunction. As such, a low CFR with preserved FFR may point to a higher microvascular resistance and unremarkable plaque burden, while a combination of low FFR with preserved CFR would indicate epicardial stenosis and preserved microvascular function.

4.3 INSTANTANEOUS WAVE-FREE RATIO

An alternative to FFR in the assessment of epicardial flow and plaque burden is the instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR), first developed and validated by Sayan et al in 2012, which is calculated as iFR = Pd / Pa during the wave-free period. The latter is defined as a phase in the diastole where the vascular resistance is relatively constant and minimized. During this phase, the trans-stenotic pressure ratio would serve as a measure of coronary stenosis severity. The major advantage of iFR over FFR is that it is a non-hyperemic pressure ratio, thus offering a cheaper and faster baseline assessment without the potential adverse effects associated with hyperemia. Nevertheless, like FFR, iFR is not able to detect microvascular dysfunction. Other limitations of iFR are sensitivity to noise, wire drift and variations in hemodynamic conditions that could modify resting coronary flow, such as contrast injection.

4.4. INDEX OF MICROCIRCULATORY RESISTANCE

First described by Fearon et al., the Index of Microcirculatory Resistance (IMR) offers a quantitative, reproducible assessment of coronary microvascular resistance by measuring distal coronary pressure and hyperemic mean transit time using thermodilution techniques. Its measurement became possible with the advent of devices able to simultaneously measure pressure and flow velocities, as well as software allowing the shaft and pressor sensor of a wire to act as proximal and distal thermistors. It was derived from Ohm’s law of resistance in a given circuit, where the resistance (R) is calculated from the ratio between the pressure gradient and flow (Q), as follows:

R = ΔP / Q

In the coronary circulation the pressure gradient is defined as distal coronary pressure (Pd) minus venous pressure, which is assumed to be zero at maximal hyperemia. During maximal hyperemia, absolute flow follows a linear relationship with the inverse of flow velocity (1/Tmn). Thus, the index of microvascular resistance can be calculated as follows:

IMR = Pd × (1 / Tmn) = Pd × Tmn

Commonly reported normal values are below 25.

Unlike coronary flow reserve (CFR), IMR is largely independent of hemodynamic variations and epicardial stenosis, making it particularly valuable in acute settings such as myocardial infarction (MI). An IMR value exceeding 40 units has been consistently linked to an increased risk of adverse outcomes, including all-cause mortality, heart failure hospitalization, and persistent myocardial injury, especially in ST-elevation MI (STEMI) patients.

Like CFR, IMR can be measured simultaneously with FFR and is helpful in discriminating epicardial from microcirculatory dysfunction. However, unlike CFR, IMR has shown better reproducibility, where mean IMR did not change with repeat measurements at baseline, during right ventricular pacing, during nitroprusside and dobutamine infusions. Recent studies emphasize IMR’s prognostic power and utility as a standalone metric for identifying microvascular obstruction and stratifying long-term risk. For example, increased IMR has been shown to be a strong predictor of post-infarct left ventricular remodeling and has proven superior to angiographic or visual assessments of microvascular damage.

Furthermore, the angiography-derived IMR (angio-IMR) presents a non-wire-based alternative that may facilitate broader adoption in routine practice without compromising diagnostic accuracy. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses support the integration of IMR into invasive coronary function testing protocols, particularly in patients with ischemia and nonobstructive coronary arteries (INOCA), and as part of a comprehensive physiologic assessment post-AMI. As the field advances, the role of IMR continues to expand, not only for risk stratification but also for guiding therapeutic decision-making in CMD.

4.5. ANGIOGRAPHY-DERIVED MICROVASCULAR RESISTANCE INDICES

Recent advancements in computational modeling and image processing have enabled the derivation of microvascular resistance indices directly from standard coronary angiography, offering a wire-free and vasodilator-free alternative to traditional invasive techniques. Among these, the angiography-derived index of microcirculatory resistance (angio-IMR) has gained attention as a practical and reproducible method for assessing coronary microvascular function during routine diagnostic procedures.

Angio-IMR leverages contrast flow dynamics and anatomical data to estimate hyperemic flow and microvascular resistance without the need for pressure wires or adenosine administration. Validation studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between angio-IMR and invasive IMR, suggesting good diagnostic accuracy in both stable ischemic heart disease and acute coronary syndromes.

Furthermore, because angio-IMR can be retrospectively calculated from angiograms, it facilitates broader implementation in both research and clinical practice, including in settings where traditional wire-based measurements are not feasible. While these technologies show promise, challenges remain regarding standardization, vendor-specific algorithms, and integration into clinical workflows. Nevertheless, angiography-derived indices represent a pivotal step toward simplifying physiologic assessment through expanding access to coronary microvascular diagnostics, particularly in patients with angina and no obstructive coronary arteries (ANOCA) or myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA).

4.6. NOVEL THERMODILUTION TECHNIQUES

Recent innovations in thermodilution methodology have led to the development of continuous thermodilution techniques, which enable real-time, quantitative assessment of absolute coronary blood flow (Q) and microvascular resistance using a dedicated infusion catheter and temperature-sensing pressure wire. Unlike traditional bolus thermodilution, which relies on manual saline injections and can be prone to variability, continuous thermodilution provides automated, operator-independent measurements that improve reproducibility and clinical utility. Comparative studies have demonstrated a high correlation between continuous and bolus thermodilution methods, with continuous thermodilution offering superior reproducibility and lower intra-individual variability.

These novel techniques have shown a strong correlation with established physiological indices such as CFR and IMR, and have demonstrated prognostic relevance, particularly in identifying patients at risk for adverse cardiac remodeling and heart failure following myocardial infarction. Importantly, continuous thermodilution allows for absolute quantification of coronary flow in mL/min, providing a more granular evaluation of microvascular function than relative indices alone. Optimization strategies, such as adjusting infusion rates and catheter positioning, have further minimized variability in flow measurements, enhancing their clinical utility.

Clinical studies also suggest that this approach may help individualize treatment strategies by distinguishing between structural and functional forms of coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD), enabling more targeted use of vasodilators, anti-anginal medications, or anti-inflammatory agents. As integration into routine catheterization lab workflows becomes increasingly feasible, continuous thermodilution is likely to play an expanding role in the comprehensive evaluation of ischemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA) and myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA).

5. Imaging and Microvascular Functional Assessment

Beyond invasive catheter-based techniques, imaging modalities have emerged as valuable tools for evaluating microvascular function:

5.1. TRANSTHORACIC SUPER-RESOLUTION ULTRASOUND LOCALIZATION MICROSCOPY

Transthoracic Super-Resolution Ultrasound Localization Microscopy (SRUS/ULM) represents a groundbreaking advancement in non-invasive cardiac imaging. This technique leverages microbubble contrast agents and ultrafast ultrasound sequences, combined with advanced spatiotemporal filtering and motion correction, to achieve spatial resolutions well below the diffraction limit of conventional ultrasound systems. In contrast to traditional echocardiography, SRUS/ULM allows for direct visualization of the myocardial microvasculature, making it uniquely suited for detecting subtle abnormalities in microvascular structure and function.

Clinical implementation of SRUS/ULM has recently become feasible, owing to innovations in both transducer design and image reconstruction algorithms. A recent pilot study by Christensen-Jeffries et al. demonstrated successful transthoracic application of this method in human subjects, capturing high-resolution maps of intramyocardial perfusion and vascular density. These capabilities are particularly significant in the context of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and ischemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA), where microvascular dysfunction often underlies persistent ischemic symptoms despite angiographically normal epicardial coronaries.

SRUS/ULM is non-invasive and radiation-free, allowing for serial imaging and longitudinal monitoring. This makes it a promising tool not only for early diagnosis but also for assessing therapeutic response, particularly in patients undergoing interventions aimed at improving coronary microvascular function. Its high spatial resolution also allows discrimination between structurally intact and remodeled microvasculature, a distinction that may hold prognostic and therapeutic significance.

Although the technology is still in its early stages of clinical validation, it holds substantial potential for integration into routine cardiovascular diagnostics. Ongoing research is focused on refining signal processing algorithms, improving acquisition speed, and validating reproducibility across patient populations with CMD, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), and post-AMI remodeling.

5.2. MYOCARDIAL PERFUSION IMAGING AND MICROVASCULAR RESISTANCE

Combining invasive measurements with advanced imaging modalities such as cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) and positron emission tomography (PET) significantly enhances the assessment of coronary microvascular function by providing both anatomical and functional insights. These multimodal approaches allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of myocardial perfusion, microvascular resistance, and the presence of microvascular obstruction (MVO), which is particularly relevant in patients with angina and non-obstructive coronary arteries.

CMR imaging, especially when using techniques such as late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and first-pass perfusion imaging, can detect areas of MVO and quantify myocardial blood flow and perfusion reserve with high spatial resolution. Quantitative perfusion CMR has shown promise in identifying abnormal microvascular responses in patients with suspected coronary microvascular dysfunction, even in the absence of epicardial disease. Recent advances in myocardial perfusion MR imaging, including high-resolution mapping and stress perfusion techniques, have improved the ability to detect subtle impairments in microvascular perfusion and correlate these findings with invasive indices such as the Index of Microcirculatory Resistance (IMR) or Coronary Flow Reserve (CFR).

Similarly, PET imaging remains a gold standard for the quantitative assessment of myocardial blood flow and coronary flow reserve. PET imaging allows for precise measurements that are reproducible across different patient populations, including those with diabetes, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and ischemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA). PET can identify diffuse microvascular dysfunction and subtle regional perfusion abnormalities, serving as a non-invasive correlation to invasive assessments such as CFR and IMR.

Importantly, the integration of PET findings with invasive coronary physiology enhances risk stratification and may guide therapeutic decision-making. In addition to these well-established modalities, emerging techniques such as angiography-derived assessments of microvascular resistance offer novel opportunities for non-wire-based functional evaluation, bridging the gap between imaging and physiology. Furthermore, developments in computed tomography (CT) perfusion imaging have enabled dynamic assessments of myocardial blood flow that may provide surrogate markers for microcirculatory impairment, expanding the diagnostic armamentarium beyond traditional methods.

Altogether, the synergy of imaging and invasive physiological assessment represents a paradigm shift in the evaluation of coronary microvascular dysfunction, allowing for more nuanced and patient-tailored management strategies.

6. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Understanding and assessing coronary microvascular function has far-reaching clinical implications that influence patient care across diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic domains.

RISK STRATIFICATION:

Microvascular dysfunction, often undetected on routine coronary angiography, has emerged as a key determinant of prognosis in both acute and chronic coronary syndromes. Identifying patients with an elevated Index of Microcirculatory Resistance (IMR) or reduced coronary flow reserve (CFR) enables clinicians to stratify risk more accurately. Patients with microvascular dysfunction are at higher risk of adverse cardiovascular events such as recurrent myocardial infarction, heart failure hospitalization, and mortality, particularly following AMI. These individuals may benefit from more intensive surveillance, lifestyle modification, and timely initiation of cardioprotective therapies.

THERAPEUTIC DECISION-MAKING:

Detailed assessment of microvascular health can guide tailored therapies. For example, patients exhibiting significant microvascular dysfunction may derive benefit from pharmacologic strategies targeting endothelial function such as ACE inhibitors, statins, or anti-inflammatory agents or interventions that modify coronary microvascular tone, including calcium channel blockers and nitrates. Novel approaches such as remote ischemic conditioning or intracoronary therapy targeting reperfusion injury are also being explored in this context. Additionally, the expanding role of imaging modalities and wire-free indices (e.g., angiography-derived IMR) offers actionable data even in patients where invasive testing is impractical.

PROGNOSTICATION:

Invasive indices such as IMR are strong predictors of long-term outcomes. A high IMR measured in the acute phase of AMI has been independently associated with larger infarct size, adverse left ventricular remodeling, and worse ejection fraction at follow-up. These findings underscore the importance of including microvascular assessment as a routine part of post-AMI evaluation not just for diagnosis, but for refining prognosis and guiding follow-up intensity. Non-invasive imaging, particularly PET and quantitative perfusion CMR, also provide prognostic insights when correlated with functional indices like CFR and microvascular resistance reserve.

PERSONALIZED MEDICINE AND MONITORING:

Repeated or longitudinal evaluation of coronary microvascular function particularly through non-invasive methods such as PET, CMR, and super-resolution ultrasound can inform ongoing treatment response or disease progression. This may prove especially valuable in patients with INOCA or MINOCA, where symptoms persist despite the absence of obstructive disease. Integrating serial imaging with invasive assessment can enable dynamic care plans that evolve with the patient’s condition.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS:

Future research should prioritize the standardization of microvascular assessment protocols and further validate novel technologies like continuous thermodilution, angiography-derived resistance indices, and super-resolution ultrasound in large, multicenter cohorts. Equally important is the exploration of new therapeutic agents specifically targeting microcirculatory function, as well as combination therapies tailored to microvascular phenotype.

Moreover, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms into microvascular diagnostics is an emerging frontier. These tools can assist in the real-time interpretation of large and complex datasets from pressure-wire tracings to perfusion imaging enhancing diagnostic accuracy and enabling fully personalized treatment strategies. Such innovations may transform coronary microvascular dysfunction from a frequently overlooked entity to a modifiable therapeutic target in the routine care of patients with ischemic heart disease.

7. Conclusion

Coronary microvascular dysfunction represents a critical yet historically under-recognized contributor to adverse outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). As contemporary revascularization strategies continue to reduce epicardial artery-related mortality, the limitations imposed by impaired microvascular perfusion have become increasingly evident. Microvascular obstruction (MVO), ischemia-reperfusion injury, and endothelial dysfunction all contribute to suboptimal myocardial recovery, despite successful epicardial intervention.

Incorporating microvascular assessment into routine clinical practice for AMI patients, particularly those with persistent symptoms or high-risk features has the potential to improve outcomes by guiding individualized care strategies. As research continues to refine these techniques and validate their prognostic utility across broader populations, the focus must now shift toward therapeutic translation. Future studies should explore pharmacologic and procedural interventions that target microvascular health directly. Moreover, the application of artificial intelligence to interpret microvascular data may streamline clinical workflows and pave the way for real-time, precision-guided management.

Ultimately, recognizing and addressing microvascular dysfunction as a central determinant of post-AMI recovery marks a pivotal step forward in achieving more complete myocardial salvage and optimizing long-term outcomes for patients with ischemic heart disease.

References

- Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics 2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56-e528. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659

- Ong P, Camici PG, Beltrame JF, et al. International standardization of diagnostic criteria for microvascular angina. Int J Cardiol. 2018;250:16-20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.08.068

- Niccoli G, Scalone G, Lerman A, Crea F. Coronary microvascular obstruction in acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(13):1024-1033. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv484

- Clarke JRD, Kennedy R, Lau FD, Lancaster GI, Zarich SW. Invasive evaluation of the microvasculature in acute myocardial infarction: Coronary flow reserve versus the index of microcirculatory resistance. J Clin Med. 2020;9(1). doi:10.3390/jcm9010086

- De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, Smith L, Wievegg M, Heyndrickx GR. Coronary Thermodilution to Assess Flow Reserve. Circulation. 2001;104(17):2003-2006. doi:10.1161/hc4201.099223

- Kaufmann PA, Namdar M, Matthew F, et al. Novel Doppler Assessment of Intracoronary Volumetric Flow Reserve: Validation Against PET in Patients With or Without Flow-Dependent Vasodilation. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2005;46 (8):1272. http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/46/8/1272.abstract

- Everaars H, de Waard GA, Driessen RS, et al. Doppler Flow Velocity and Thermodilution to Assess Coronary Flow Reserve: A Head-to-Head Comparison With [15O]H2O PET. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(20):2044-2054. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2018.07.011

- Perera D, Berry C, Hoole SP, et al. Invasive coronary physiology in patients with angina and non-obstructive coronary artery disease: A consensus document from the coronary microvascular dysfunction workstream of the British Heart Foundation/National Institute for Health Research Partnership. Heart. 2022;109(2):88-95. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2021-320718

- Pijls NH, van Son JA, Kirkeeide RL, De Bruyne B, Gould KL. Experimental basis of determining maximum coronary, myocardial, and collateral blood flow by pressure measurements for assessing functional stenosis severity before and after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Circulation. 1993;87(4):1354-1367. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.87.4.1354

- Pijls NHJ, Van Gelder B, Van der Voort P, et al. Fractional Flow Reserve. Circulation. 1995;92(11):3183-3193. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.92.11.3183

- Ahn SG, Suh J, Hung OY, et al. Discordance Between Fractional Flow Reserve and Coronary Flow Reserve: Insights From Intracoronary Imaging and Physiological Assessment. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(10):999-1007. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2017.03.006

- Sen S, Escaned J, Malik IS, et al. Development and Validation of a New Adenosine-Independent Index of Stenosis Severity From Coronary Wave Intensity Analysis: Results of the ADVISE (ADenosine Vasodilator Independent Stenosis Evaluation) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(15):1392-1402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.003

- Fezzi S, Huang J, Lunardi M, et al. Coronary physiology in the catheterisation laboratory: an A to Z practical guide. AsiaIntervention. 2022;8(2):86-109. doi:10.4244/AIJ-D-22-00022

- Kogame N, Ono M, Kawashima H, et al. The Impact of Coronary Physiology on Contemporary Clinical Decision Making. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(14):1617-1638. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2020.04.040

- De Maria GL, Garcia-Garcia HM, Scarsini R, et al. Novel Indices of Coronary Physiology. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(4):e008487. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.119.008487

- Fearon WF, Balsam LB, Farouque HMO, et al. Novel Index for Invasively Assessing the Coronary Microcirculation. Circulation. 2003;107(25):3129-3132. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000080700.98607.D1

- Mangiacapra F, Viscusi MM, Paolucci L, et al. The Pivotal Role of Invasive Functional Assessment in Patients With Myocardial Infarction With Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA). Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;Volume 8-2021. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.781485

- Verma SK, Kumar B, Bahl VK. Aorto-ostial atherosclerotic coronary artery disease Risk factor profiles, demographic & angiographic features. IJC Heart & Vasculature. 2016;12:26-31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcha.2016.05.016

- Martínez GJ, Yong ASC, Fearon WF, Ng MKC. The index of microcirculatory resistance in the physiologic assessment of the coronary microcirculation. Coron Artery Dis. 2015;26. https://journals.lww.com/coronary-artery/fulltext/2015/08001/the_index_of_microcirculatory_resistance_in_the.5.aspx

- Luo C, Long M, Hu X, et al. Thermodilution-Derived Coronary Microvascular Resistance and Flow Reserve in Patients With Cardiac Syndrome X. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(1):43-48. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.113.000953

- Melikian N, Vercauteren S, Fearon WF, et al. Quantitative assessment of coronary microvascular function in patients with and without epicardial atherosclerosis. EuroIntervention. 2010;5(8). https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJV5I8A166

- Giampaolo N, Francesco B, Leonarda G, Filippo C. Myocardial No-Reflow in Humans. JACC. 2009;54(4):281-292. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.054

- Ng MKC, Yeung AC, Fearon WF. Invasive Assessment of the Coronary Microcirculation. Circulation. 2006;113(17):2054-2061. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.603522

- de Waha S, Patel MR, Granger CB, et al. Relationship between microvascular obstruction and adverse events following primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: an individual patient data pooled analysis from seven randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(47):3502-3510. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx414

- De Maria GL, Scarsini R, Shanmuganathan M, et al. Angiography-derived index of microcirculatory resistance as a novel, pressure-wire-free tool to assess coronary microcirculation in ST elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;36(8):1395-1406. doi:10.1007/s10554-020-01831-7

- Fearon WF, Kobayashi Y. Invasive Assessment of the Coronary Microvasculature. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(12):e005361. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.117.005361

- Carrick D, Haig C, Ahmed N, et al. Comparative Prognostic Utility of Indexes of Microvascular Function Alone or in Combination in Patients With an Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2016;134(23):1833-1847. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022603

- R TV, F DCM. Coronary Microvascular Disease Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Options. JACC. 2018;72(21):2625-2641. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.042

- Rehan R, Yong A, Ng M, Weaver J, Puranik R. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: A review of recent progress and clinical implications. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;Volume 10-2023. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2023.1111721

- Abramik J, Mariathas M, Felekos I. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Vasospastic Angina Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management Strategies. J Clin Med. 2025;14(4). doi:10.3390/jcm14041128

- Takahashi T, Gupta A, Samuels BA, Wei J. Invasive Coronary Assessment in Myocardial Ischemia with No Obstructive Coronary Arteries. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2023;25(10):729-740. doi:10.1007/s11883-023-01144-9

- Christensen-Jeffries K, Couture O, Dayton PA, et al. Super-resolution Ultrasound Imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020;46(4):865-891. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.11.013

- Gallinoro E, Bertolone DT, Mizukami T, et al. Continuous vs Bolus Thermodilution to Assess Microvascular Resistance Reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16(22):2767-2777. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2023.09.027

- Gallinoro E, Bertolone DT, Fernandez-Peregrina E, et al. Reproducibility of bolus versus continuous thermodilution for assessment of coronary microvascular function in patients with ANOCA. EuroIntervention. 2023;19(2):e155-e166. doi:10.4244/EIJ-D-22-00772

- Jansen TPJ, de Vos A, Paradies V, et al. Continuous Versus Bolus Thermodilution‐Derived Coronary Flow Reserve and Microvascular Resistance Reserve and Their Association With Angina and Quality of Life in Patients With Angina and Nonobstructive Coronaries: A Head‐to‐Head Comparison. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(16):e030480. doi:10.1161/JAHA.123.030480

- De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, Gallinoro E, et al. Microvascular Resistance Reserve for Assessment of Coronary Microvascular Function: JACC Technology Corner. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(15):1541-1549. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.08.017

- Minten L, Bennett J, McCutcheon K, et al. Optimization of Absolute Coronary Blood Flow Measurements to Assess Microvascular Function: In Vivo Validation of Hyperemia and Higher Infusion Speeds. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17(7):e013860. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.123.013860

- Fernandes J, Ferreira MJ, Leite L. Update on myocardial blood flow quantification by positron emission tomography. Revista Portuguesa de Cardiologia (English Edition). 2020;39(1):37-46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repce.2020.03.007

- Crooijmans C, Jansen TPJ, Meeder JG, et al. Safety, Feasibility, and Diagnostic Yield of Invasive Coronary Function Testing: Netherlands Registry of Invasive Coronary Vasomotor Function Testing. JAMA Cardiol. 2025;10(4):384-390. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2024.5670