Air Embolism: Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment Challenges

Air embolism- Incidence of Uncommon Causes, Diagnostic and Treatment Challenges

Ni, Eric¹; Bhaskar, Rahill¹; Borochaner, Seth¹; Garg, Ria²*

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED 31 August 2025

CITATION

Eric, N., Rahill, B., et al., 2025. Air embolism- Incidence of Uncommon Causes, Diagnostic and Treatment Challenges. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6891

ABSTRACT

An air embolism is a condition in which air or gas enters the vasculature in either the venous or arterial systems resulting in an obstruction of circulation potentially leading to serious complications such as acute stroke, respiratory arrest, cardiac arrest, or myocardial infarction. While the etiology of most air embolisms is iatrogenic from interventions such as invasive procedures, hemodialysis or neurosurgery, it is also important to recognize uncommon causes of air embolisms. These uncommon causes include decompression (i.e., from scuba diving), percutaneous transthoracic lung biopsy, cardiopulmonary bypass, intraabdominal laparoscopic surgery and ventilator associated air embolism. The most common pathophysiology is based on pressure difference in the vasculature, others include direct trauma or paradoxical air embolism. The clinical presentation of venous and arterial air embolisms is variable, atypical, and depends on volume of air, rate, route of entry, organs affected; making diagnosis challenging. Diagnostic methods include imaging modalities such as Echocardiogram, Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), Point of care ultrasound (POCUS), Doppler ultrasonography, Computed tomography (including CT pulmonary angiogram), Magnetic resonance imaging. Treatment is based on the type and severity of embolism as status. It requires supportive care and definitive treatment like hyperbaric oxygen therapy, aspiration or Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in severe cases. Air embolism comes with its own diagnostic challenges-atypical clinical presentation, low sensitivity of most imaging techniques, lack of clinical awareness, and treatment challenges-limited availability of hyperbaric oxygen chambers, lack of standardized treatment protocols, limited data on adjunctive treatment methods. Proposed solutions for these challenges include emphasizing on standardization of diagnostic and treatment protocols, artificial intelligence integration, rapid imaging access, continued medical education, referral networks for HBOT and evidence-based research.

Keywords

air embolism, diagnosis, treatment, challenges, uncommon causes

THE EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF MEDICINE

Medical Research Archives, Volume 13 Issue 8

REVIEW ARTICLE

Introduction and aim:

Air embolism is defined as a medical condition where air or gas in the form of bubbles enters the vasculature, either the venous or arterial bloodstream and can cause obstruction of blood flow. This can also lead to serious complications like acute stroke, respiratory arrest, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction. This is mostly an iatrogenic problem, some of the common reasons are invasive procedures, surgical procedures, hemodialysis, neurosurgery. Some of the other uncommon causes of air embolism include decompression for example during scuba diving, penetrating chest trauma, cardiopulmonary bypass, intra-abdominal laparoscopic surgery, patent foramen ovale. Most common pathophysiology behind air embolism is rooted in pressure differences between atmospheric and intravascular pressure which allows air to enter the circulation, especially when the intravascular pressure is lower. Some examples are insertion of central venous catheters or open venous procedures. Rarely, a patent foramen ovale can lead to paradoxical air embolism when air bubbles enter the systemic arterial circulation. Regardless of the pathophysiology, this can lead to potentially fatal consequences and ischemic injuries to vital organs.

Clinically, the presentation can be variable and atypical. Venous air emboli usually present during or after a culprit procedure with respiratory or cardiac symptoms. But arterial air emboli usually manifest within seconds to minutes and are mostly associated with neurological symptoms. Despite its catastrophic consequences, air embolism remains an underrecognized and underreported condition. The exact incidence is not clearly known given variable presentation, subclinical events and limited reporting in literature. Case reports and retrospective studies suggest a wide variation in incidence, which is mainly influenced by the type of procedure, experience of the practitioner and institutional protocols. For example, central venous catheter insertion is one of the most common causes with incidence ranging from 0.1-1%. On the other hand, neurosurgical procedures in the pediatric population, particularly performed in the sitting position have been reported to cause air embolism at a rate of as high as 80%.

The diagnostic methodology can be inherently challenging given the diversity of etiology and variable presentation. There is no specific laboratory biomarker, but some imaging modalities including Computed Tomography (CT), and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and ultrasound are being used and have varying degrees of sensitivity and specificity, which further depends on the timing, volume of air and affected vasculature. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is a valuable tool for intraoperative diagnosis and Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) is being increasingly used in the emergency and critical care settings at the bedside.

Management involves a combined approach with immediate supportive measures like high-flow oxygen therapy, patient positioning and cardiovascular stabilization; plus definitive treatments like hyperbaric oxygen therapy. In some severe cases, extra corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or aspiration of intravascular air is performed. However, there are several challenges including timely diagnosis, access to facilities with hyperbaric oxygen chambers, lack of standardized treatment protocols, limited education and awareness amongst providers and resource limitations in certain settings.

In this review, we aim to cite the incidence of uncommon causes of both venous and arterial air embolism, after comprehensive research of literature. This paper also highlights the diagnostic and treatment challenges for this life-threatening condition and provides potential solutions in clinical practice. By addressing these gaps in current knowledge and emphasizing the need for standardized care protocol, it provides opportunities to improve outcomes in patients affected by air embolism.

Pathophysiology of air embolism:

Most common mechanism for development of air emboli is difference in pressure gradients within the bloodstream forcing the gas bubbles to move directly into systemic circulation. This is typically observed in patients experiencing changes in atmospheric pressure, such as scuba divers during an ascent. When inserting or removing a central venous catheter or opening veins during surgery, air enters a vein because the venous pressure is lower than the atmospheric pressure. Negative intrathoracic pressure during inspiration can worsen the embolism by promoting air entry.

Another more common pathophysiology of air embolism formation is direct mechanical injury or chest trauma, which precipitate the formation of gas bubbles within the pulmonary vasculature and eventually air embolism within the lungs. Air bubbles will travel to the right heart chambers, then to the pulmonary artery and raise the pulmonary artery pressure, cause right heart strain, hypoxia and cardiovascular (CV) collapse.

If a patent foramen ovale or pulmonary shunt is present, emboli will travel to the arterial circulation and cause ischemic events in other anatomic locations such as the brain and heart or other end organs, causing catastrophic consequences for the patients. Emboli in the vessel microcirculation can initially allow some blood flow, but turbulent blood flow around the air will activate platelets, fibrin, complement and proteins causing thrombosis and obstruction. The combined effect can cause microthrombi formation, endothelial disruption, impaired perfusion and mechanical obstruction. This clinically manifests as vasogenic edema, neurological compromise, hypotension, hypoxia and CV collapse.

Clinical Presentation of air embolism:

Clinical presentation depends on volume of air, rate, route of entry, and organs affected. An arterial air embolism tends to develop within seconds to minutes with dramatic neurologic symptoms. Delayed manifestations are seen when small emboli enter at a slow rate or when entering from the venous to arterial system. They typically affect the cerebrovascular system, and so the symptoms are often related to the vascular territory that is perfused by the affected vessel. Multiple cerebrovascular territories are often affected. Common manifestations include loss of consciousness, confusion, presyncope, stroke-like symptoms, or seizures. As these symptoms can also be associated with more common cerebrovascular pathologies such as ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes, arterial air embolisms present a unique diagnostic challenge. Cardiac embolism can present with chest pain, arrhythmias, myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest.

Venous air emboli, however, are variable in clinical presentation, severity, and affected organ system and are usually seen rapidly during or after a procedure. Common symptoms include lightheadedness, dyspnea, tachypnea, chest pain, and even feeling of impeding death. Abnormal signs on exam include tachycardia, tachypnea, hypoxia and hypotension. A only specific sign of air embolism which occurs when a large air bolus is present in the right ventricle, which is classic but rare. Central nervous system (CNS) symptoms may present as altered mental status, focal deficits, coma. Although, these CNS symptoms are a consequence of hypoxia or hypotension rather than cerebrovascular arterial occlusion, as is the case with arterial air emboli. Lung exam can reveal rales or wheezes shortly after an air embolism occurs. Arterial blood gas from patients with venous air embolism would demonstrate ventilation and perfusion mismatch. Hypercarbia can also be seen. In severe cases, all kinds of air embolism can lead to cardiovascular collapse.

Epidemiology and incidence of air embolism:

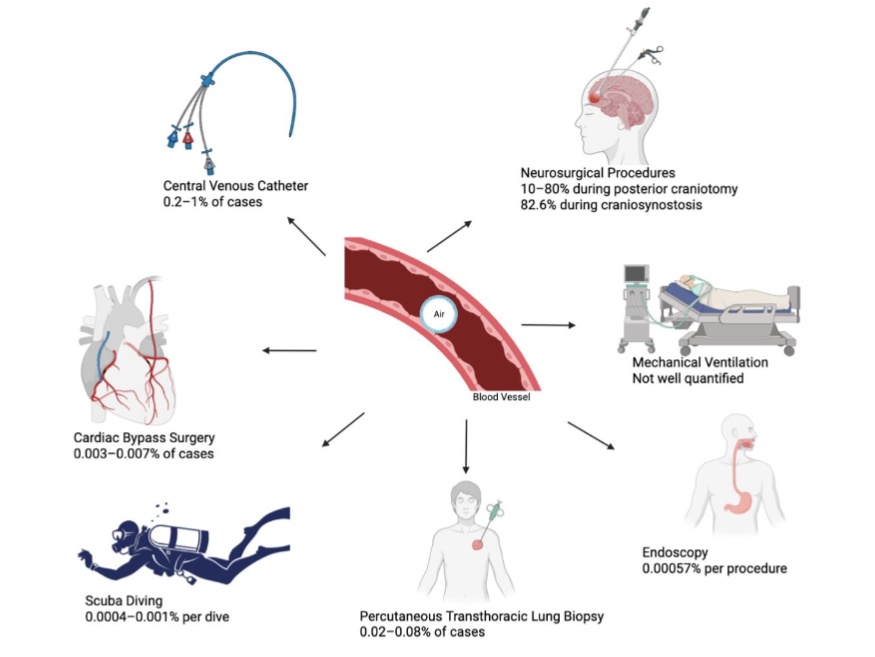

The exact incidence of air embolism is hard to determine because of varied clinical presentation, difficult diagnosis, poor documentation, transient or subclinical embolus. Incidence varies depending on type of procedure, expertise of the physician or hospital setting. One retrospective study of 67 confirmed cases over 25 years found that 94% cases of air embolism occurred in-patient and 77.8% were during an operative procedure. Details of incidence and prevalence categorized based on common and uncommon causes as below:

| Cause | Incidence / Prevalence |

|---|---|

| Central Venous Catheter procedures | 0.2-1% of cases (1 in 473,000) |

| Neurosurgery (e.g., sitting craniotomy) | 80% during posterior craniotomy; 82.6% during craniosynostosis |

| Cardiac bypass surgery | 0.003-0.007% of cases |

| Hospitalized arterial embolism overall | 0.00265% (2.65 per 100,000) |

| Diving (scuba) | 0.0004-0.001% per dive; 0.007% per diver |

| PTLB (symptomatic) | 0.02-0.08% of cases |

| Endoscopy (overall) | 0.00057% per procedure |

| Ventilator/trauma-related | Not well quantified; rare, barotrauma common |

Common Causes of Air Embolism:

CENTRAL VENOUS CATHETER PROCEDURES:

A very high incidence of venous air embolism is seen with Central venous catheter (CVC) procedures and account for the largest percentage of air embolisms. A single center study done at a large university hospital across a five-year period showed relatively low incidence of air embolism, and most of these patients were either asymptomatic or experienced mild symptoms. General CVC placement or removal causes about 0.2-1% cases. Interventional radiology and use of catheter with contrast accounts for about 0.13% incidence.

NEUROSURGICAL PROCEDURES:

Neurosurgical procedures tend to have variable incidence of air embolism, with some procedures having higher incidence than others. Neurosurgical procedures account for about 10-80% of incidents during posterior craniotomies especially during sitting position. In a prospective study over a 2-year period with 23 patients, Craniosynostosis repair (pediatric craniectomy) accounted for 82.6% of cases affected with venous embolism and 31.6% of those had associated hypotension. One single center prospective two-year study found a greater than 80% incidence rate for air embolism occurrence in a pediatric population. Most of these patients experienced mildly symptomatic to asymptomatic hypotension, and none of the patients developed obstructive or cardiogenic shock. There is debate as to whether this can be prevented with positional changes with some researchers arguing that the sitting position can actually prevent formation of venous air embolisms. A single center retrospective analysis found a relatively high rates of venous air embolism formation (23%) in adults undergoing neurosurgical procedures compared to children (28%), in the sitting position. These rates are similar to the studies mentioned above.

Uncommon Causes of Air Embolism:

CARDIAC BYPASS SURGERY:

Patients undergoing cardiac bypass surgery have occasionally noted to develop coronary arterial air embolisms. Complications include coronary arterial vasospasms that can be fatal for patients. Prevalence of arterial embolism can be as low as 0.003% and 0.007% in patient undergoing cardiac bypass surgery, but about half of these patients can have serious outcomes. Intracoronary embolism incidence has been reported to be 0.2% which can vary depending on the type of angiography and expertise of the physician. One single center retrospective study found an incidence rate of 0.19% for clinically significant coronary arterial air embolisms.

DIVING:

Given the pathophysiology of air embolism, it is surprising that scuba diving and other diving sports have a relatively low incidence rate of air embolism. Multiple retrospective cohort studies have examined incidence rate of decompression sickness in divers but did not report specific incidence rate for air embolism. True incidence of arterial embolism remains unknown because of varying clinical presentation and difficult diagnoses. However, literature suggests that for scuba diving the incidence has ranged between 0.4 -1 per 100,000 dives, which is worse with deeper and longer dives.

ENDOSCOPY PROCEDURES:

Air embolism rarely can present with or without vascular injury to the gastric mucosa in endoscopy procedures, most seen in patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Many of these air emboli cases have resulted in severe symptoms and even hemodynamic compromise in patients. In a study that evaluated patients undergoing endoscopy from 1998 to 2013, found a rate of 0.57 cases of air embolism per 100,00 endoscopy procedures. Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) air embolism was most common, with the rate of 3.32 per 100,000 procedures, 0.44/100,000 for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), 0.38/100,000 for colonoscopy. A study taking data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 1995 to 2013 revealed an incidence rate of 3.32 per 100,000 ERCP procedures and recorded a post endoscopic air embolism case fatality rate of 15.4%. The odds ratio for developing air embolisms in patients undergoing EGD and Colonoscopy procedures were significantly lower, and no data was recorded on the incidence rate in patients undergoing sigmoidoscopy. Another systematic review paper reported cases of systemic air embolism in patients undergoing endoscopy procedures. Most of these cases involved patients undergoing ERCP and almost half of the cases involved patients with a patent foramen ovale on echocardiogram.

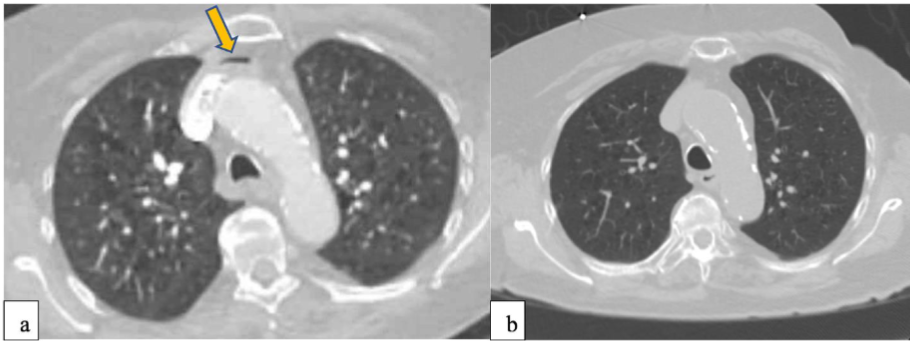

PERCUTANEOUS TRANSTHORACIC LUNG BIOPSY:

Given the highly vascularized nature of the lung, it is no surprise that air embolism can occur after lung trauma. Similarly, air embolisms can occur after Percutaneous Transthoracic Lung Biopsy (PTLB). In a systematic review, the combined incidence of air embolism after PTLB was found to be 0.08% and one third of these patients suffered disease sequelae or died. The same study also noted an increase in air embolism events and more adverse outcomes with aspiration biopsy compared to core biopsy.

VENTILATOR ASSOCIATED AIR EMBOLISMS:

It is hypothesized that recurrent aspiration and trauma from intubation are contributing factors to this pathology and has been reported only in case studies. There is very limited data on positive pressure ventilation or barotrauma causing embolism, but a case report suggests that a systemic air embolism may have occurred following barotrauma and tension pneumothorax in a patient leading to further complications.

Diagnostic Methods:

The diagnosis of air embolism can be challenging due to its diverse, clinical manifestations, the absence of specific and targeted laboratory biomarkers, and limitations on current imaging modalities. However, in recent years significant development and integration of advanced imaging techniques has been made.

Imaging plays an adjunctive role in confirming the presence of intravascular air, assessing downstream complications, and excluding alternative diagnosis. The primary imaging modalities employed includes echocardiogram, including thoracic, transesophageal, intracardiac, precordial; Doppler ultrasound; Point of care ultrasound (POCUS); Computed Tomography (CT), and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is still considered the gold standard for interoperative and preoperative attraction of venous air embolism. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can detect small volumes of air however; sensitivity is limited for micro bubbles and is dependent on operator comfort and capabilities. Intracardiac echocardiogram does demonstrate higher sensitivity, however, is extremely invasive and not routinely used. Transthoracic echocardiography and POCUS are less sensitive than TEE however widely available and noninvasive.

Computed Tomography (CT) and Computed Tomography Pulmonary Angiogram (CTPA) study are not sufficiently sensitive for the detection of small or transient air emboli. They may, however, incidentally reveal large volumes of air in the heart, pulmonary artery, or systemic circulation. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is even less sensitive for acute air and not recommended in the setting of emergent diagnosis. They both are useful for identifying complications or excluding alternative diagnoses. Specifically in pediatric populations CT angiography is the preferred modality for detecting pulmonary emboli but has limited use in diagnosing air emboli.

Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) is increasingly being employed as a rapid diagnostic tool for suspected air embolism. This is especially employed in perioperative, critical care, and emergency settings. Its primary use is to expedite the diagnosis and guide immediate management decisions. Air emboli appear as brighter, echogenic artifacts near the pulmonary valve and the use of POCUS is explicitly stated in American Academy Pediatrics.

No specific laboratory biomarkers are specific or sensitive for the detection of air embolism. Laboratory testing can be used to rule out alternative diagnosis or assess complications such as hypoxemia. Some evidence suggests monitoring of end-tidal carbon-di-oxide (etCO2) may point to evidence of air emboli by detecting sudden changes in carbon-dioxide (CO2) levels secondary to impaired pulmonary artery perfusion.

Recent advances in technology have improved the clinical utility of imaging in the diagnosis of air emboli. Photon counting CT (PCCT) allows for more precise differentiation of intravascular materials, including small gas bubbles, and may improve the detection of subtle or early air envelope. This technology offers improved spatial resolution, enhanced contrast to noise ratio, and the ability to acquire full spectral multi energy data. Additionally, dual energy CT and iodine mapping techniques similarly allow for more precise characterization of vascular filling defects, which may potentially improve the differentiation between air, thrombus, and other intravascular material.

Much emphasis has been placed on advancements in ultrasound techniques due to their utility and critical care environment, rapid deployment, and low cost operation. Micro bubble based ultrasound contrast agents have been employed to enhance the echogenicity of intravascular air, potentially improving the sensitivity of ultrasound for detecting small or occult air emboli.

With the advancement in artificial intelligence, deep learning algorithms can automate the identification and qualification of intervascular error on CT, improve interpretation of point of care, ultrasounds, and transferring on Doppler studies. As with most other imaging studies these AI driven tools may potentially improve reproducibility, enable the detection of small air emboli that are not seen by the human eye, reduce operator dependence, and enable rapid assessments of imaging studies.

Treatment:

Based on the type, severity of embolism and approach differs. Some of the treatment measures are outlines as below:

1) IMMEDIATE MEASURES:

- Prevent air entry: Urgent sealing or removal of the source of air embolism is required if the air source is known and iatrogenic like during intravenous line manipulation or central line insertions, laparoscopic surgeries, positive pressure ventilation, neurosurgery. This will help prevent the extension of air embolus and hemodynamic collapse or end-organ damage. Air entry can be prevented by prompt exposure of the surgical field, clamping or withdrawal of central lines, tightening catheter caps, occlusive dressings, or applying pressure. McCarthy et al. reported that a delay in achieving sealing of air entry can increase the likelihood of systemic air embolization or paradoxical embolism and lead to hemodynamic deterioration.

- Patient Position: can help distribute intravascular air and prevent progression of the air embolus. The Durant maneuver involves keeping the patient in left lateral decubitus position with head lowered, also called the Trendelenburg tilt. It is recommended when venous embolism is suspected. This position helps reduce the amount of air that can enter the pulmonary artery and therefore prevent further cardiovascular collapse by trapping air in the right atrium apex. If a patent foramen ovale is present, this same positioning can help reduce the likelihood of air entering the systemic circulation through a paradoxical embolism. However, clinical evidence for improved outcomes with this maneuver is limited and only anecdotal, despite physiological rationale and animal studies. Therefore, it should only be used as a supportive measure until definitive therapy is started.

- High flow oxygen: High flow oxygen at 100% oxygen should be started as soon as possible once air embolism is suspected. This is based on the principle of Henry’s law, which facilitates nitrogen washout from intravascular bubbles because of a diffusion gradient that’s produced by the high inspired oxygen concentration, thereby reducing the size of the air embolism. Additionally, this oxygenation increases the transport of oxygen to the tissues which thereby leads to reduced hypoxia and ischemia caused by vascular obstruction. Early oxygen delivery has shown improved outcomes in such situations in both animal studies and clinical situations, especially when this is used with other definitive therapies like hyperbaric oxygen.

2) CARDIOVASCULAR AND RESPIRATORY SUPPORT:

- Circulatory support: A large volume air embolism can cause significant cardiovascular collapse which includes reduction in cardiac preload, right ventricular dysfunction and subsequently obstructive shock. In this situation, its critical to immediately restore volume by administering intravenous fluids, mainly isotonic crystalloids to increase central venous pressure which helps reduce the negative pressure gradient that causes air to be trapped into the venous circulation. This increase in central venous pressure can further limit air entry, more importantly in low pressure venous systems like during inspiration or open vascular procedures. If cardiogenic shock is also present, vasopressors and inotropes are indicated. Norepinephrine is used as first line to maintain mean arterial pressure and systemic vascular resistance. Dobutamine which is an inotropic agent is added when right ventricular dysfunction is also present and helps improve cardiac contractility and cardiac output. These measures particularly help when mechanical obstruction is present in the pulmonary outflow tract caused by intravascular air which is a common site of venous air embolism.

- Mechanical ventilation: Patients who develop refractory hypoxia and respiratory failure, or mental status changes because of cerebral air embolism are mechanically ventilated. This ensures oxygen delivery and wash out of carbon dioxide, also decreasing the work of breathing. However, when using positive pressure ventilation, it is important to be cautious as high inspiratory pressures can worsen venous air entry from a damaged vascular endothelium or open surgical sites. It is recommended to use permissive hypercapnia and other lung protective strategies like low tidal volumes and moderate levels of positive end expiratory pressures to avoid barotrauma.

- Invasive monitoring: continuous invasive monitoring using tools like central venous pressure monitoring and arterial lines, or echocardiography can be used in patients who are hemodynamically unstable to help guide volume resuscitation. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can be useful for monitoring right heart function and detecting air in the heart chambers.

3) ADVANCED TREATMENT:

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: This is a definitive treatment for moderate to severe cases of air embolism, typically arterial and cerebral embolism. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) increases the atmospheric pressure around the patient to about 2.5-3.0 atmosphere absolute (ATA) in a chamber. Based on Boyle’s law (gas volume is inversely proportional to pressure), this increase in pressure compresses the emboli, reducing the volume of the air bubbles and leads to their dissolution and clearance from the circulation. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) also increases the partial pressure of oxygen leading to improved oxygen delivery to ischemic tissues despite vascular obstruction. This causes nitrogen washout from the emboli because of a diffusion gradient and further increases absorption of the air bubbles. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) suppresses leukocyte adhesion, increases mitochondrial function, reduces cerebral edema contributing to neuroprotection. However, time is of essence as previous studies have shown that initiating therapy sooner, typically within six hours of symptom onset leads to better neurological recovery and lower mortality. But delayed HBOT should still not be held because studies have shown it still prevents end organ ischemia in patients with persistent deficits.

- Aspiration: Aspiration of intravascular air can be used when life threatening air embolism is present, especially if a CVC is already in place with its tip in or near the right atrium. This helps to remove the air embolus before it travels to the pulmonary or paradoxically to the systemic vasculature. It can also be attempted using a syringe attached to a catheter using imaging guidance with fluoroscope or echocardiography to confirm catheter and air bubble location. This is particularly effective when large volume embolus is present in the right atrium or ventricle. Previous studies have shown successful aspiration of about 50-100 ml of air from the right heart chambers improving signs of obstructive shock. This technique is also time sensitive, needs a well-positioned catheter, catheter should be patent, and physician expertise is necessary. However, if air has migrated to the vasculature, aspiration may not be effective. Aspiration can be used as an adjunct or bridge to definitive treatment or if hyperbaric oxygen therapy is delayed and when a CVC is already in place.

4) ADDITIONAL INTERVENTIONS:

- Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation: This is considered as a salvage therapy in patients who have cardiovascular collapse that is refractory to other resuscitative measures. It is a form of advanced life support that takes over cardiac and respiratory functions temporarily. It can help maintain perfusion by allowing time for air to dissolve in the setting of a massive venous air embolism or paradoxical arterial embolism with significant hemodynamic instability. This is achieved by controlled oxygen delivery and circulatory rest. Veno-arterial Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is used in patients who have right ventricular failure, cardiogenic shock or arrest because of pulmonary vascular obstruction. Some case series and reports have demonstrated successful outcome on ECMO in cases with massive air embolism with refractory shock.

- Seizure management: Cerebral air embolism is one of the most dreaded complications of arterial embolization, caused by paradoxical embolism, direct arterial trauma, or retrograde venous ascent into the cerebral veins and can manifest with altered mental status, focal deficits, coma or seizures because of ischemic injury. It is essential to minimize secondary brain injury by preventing seizures. Seizures can increase cerebral metabolic demand and intracranial pressure exacerbating this ischemic injury. Anti-epileptic drugs like benzodiazepines are effective for initial seizure control, followed by longer acting agents like phenytoin, levetiracetam or valproate. Continuous neurological monitoring including EEG may also be warranted in critically ill patients if nonconvulsive status epilepticus is suspected. Management should be based on patient’s condition, with close monitoring of airway, intracranial pressure, and cerebral perfusion.

Challenges and proposed solutions:

DIAGNOSTIC CHALLENGES:

- Clinical presentation: One of the biggest diagnostic challenges is that air embolism can present with non-specific and variable symptoms. The symptoms can mimic disorders like pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, infectious diseases/sepsis, stroke and other cardiovascular, neurological or respiratory emergencies. When associated with uncommon causes like gastrointestinal procedures for example ERCP or laparoscopic surgery, presentation may mimic complications like perforation, peritonitis, or GI bleeding. For example, embolism during endoscopy can result in hemodynamic compromise, which can initially be attributed to sedation or perforation. This makes the diagnosis of air embolism very challenging and can lead to delays as well as misdiagnosis. Therefore, high degree of suspicion is necessary when faced with a clinical picture of cardiovascular or neurological deterioration during or after procedure.

- Proposed Solutions:

- Clinical decision support tools- Integrating real-time alerts into EHR can flag patients with potential to develop air embolism undergoing high-risk procedures.

- Standardized symptoms checklist- Developing symptom checklist for specific procedures to facilitate early recognition of air embolism.

- Simulation-based training- Incorporating scenario-based training for healthcare providers including Emergency room (ER) physicians, ICU staff and perioperative teams.

- Procedure Consent- Updating informed consent forms with risks of air embolism to increase patient and provider awareness.

- Point-of-care protocols- Creating procedural protocols to evaluate for differential diagnosis of air embolism if certain clinical features are noted, e.g., sudden hemodynamic compromise during a procedure.

2). Diagnostic tests:

When air embolism is in the early or low volume stages, imaging modalities like CT, CT pulmonary angiogram have low sensitivity for diagnosis of smaller emboli, or distal emboli in the coronary, cerebral or spinal vasculature. Furthermore, emboli may have been dissolved in the circulation by the time CT is done and this may lead to a false negative result. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) can be more sensitive in detecting cerebral changes but it’s availability and use is less practical in acute settings given long acquisition times. Diffusion weighted (DWI) MRI can help In diagnosis of ischemic injury even when air bubbles are not seen or dissolved.

Proposed Solutions:

- Rapid access imaging pathways- Establishing rapid imaging algorithms in the ER or acute settings like stroke or acute myocardial infarction protocols, when cerebral or coronary air embolism is suspected can help in early diagnosis. For example, getting an early CT when degree of suspicion is high or TEE can help document the presence of air in cardiac chambers and great veins and show evidence of right ventricular dysfunction.

- POCUS protocol standardization- Training providers in using a POCUS and Doppler can be helpful when embolism is suspected, and it can detect right heart strain as well as micro bubbles in real time.

- Advanced imaging availability- Ensuring availability of advanced MRI techniques like DWI when other modalities are inconclusive.

- Artificial intelligence integration- Investing in AI models that have recently been applied for diagnosis of acute stroke and can provide the framework for detection of air embolism related brain injury as well. Deep learning models have shown high accuracy for diagnosis of ischemic injury, calculating in fact volume, age of infarct, which is based on external validation using large datasets for CT. Similarly, trained algorithms could be used in detecting intravascular or intra cerebral air emboli on CT and can help increase the sensitivity of this emerging modality in diagnosis of air embolism.

- Portable imaging- Exploring the use of portable imaging solutions e.g., transcranial doppler, infrared spectroscopy for rural or resource-limited settings.

3). Lack of clinical awareness:

Under recognition of air embolism is common given rare presentation especially due to uncommon causes, this happens more in outpatient and low resource settings. Many cases also present acutely, are resolved spontaneously or are masked by other acute illnesses. There is lack of standardized training or awareness and education about diagnosis of this condition leading to misdiagnosis.

Proposed Solutions:

- Mandatory curriculum- Incorporating standard education and training protocols in the medical school curriculum and physicians should be encouraged to attend continuing education programs.

- Continued Medical Education- Developing and offering online CME modules and simulations focused on recognition and treatment of air embolism.

- Research and Database- Encouraging publication of case reports and literature on the topic can also raise awareness. Developing national/international registries to record cases of air embolism to highlight prevalence.

- Awareness campaign- Publishing infographics, guides, symptom cards for patients undergoing specific procedures to increase visibility.

- Clinical auditing tools- Implementing quality improvement tools to monitor complications and prompt documentation review after procedures.

TREATMENT CHALLENGES:

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: Timely administration of HBOT is extremely important and access to hyperbaric facilities is limited to mostly higher level of care centers. As discussed above, HBOT is most effective if delivered within a certain time window. Transportation delays may lead to unnecessary loss of precious time to administer HBOT. When available, most HBOT chambers are only for-the-clock, adding to logistical issues. From a clinical perspective, the patient needs to be stabilized prior to transfer. Secondly, HBOT is contraindicated in patients with pneumothorax. Lastly, lack of education or awareness amongst providers can lead to delay in initiation of treatment.

- Proposed Solutions:

- Mobile Hyperbaric oxygen therapy units- Developing and operating mobile HBOT units in under-served and remote areas.

- Referral networks- Developing regional referral networks connecting rural hospitals with HBOT centers.

- Telemedicine- Using telemedicine consultations to help in early diagnosis and initiation of therapy or HBOT referral, thereby reducing diagnostic-to-transfer delay.

- Policy- Advocating for policy change to expand HBOT, incentivize longer working hours for HBOT equipped centers, especially in underserved areas.

- Simulation training- Creating standardized protocols for training ER or rural center staff on stabilizing patients before transfer to higher level of care.

Standardized Protocols:

There is lack of universally accepted protocols for management of air embolism. For HBOT as well, the treatment regimens involving dosing, initiation timings are varied across institutions. US navy has developed a protocol to help physicians with treatment using the U.S Navy Table 6, but its use is inconsistent, and consensus driven guidelines are necessary for universal standardization. There is also inconsistent data on using anticoagulation or antiplatelets given increased risk of bleeding from a procedural aspect; patient positioning; imaging modality to select for each case.

Proposed Solutions:

- Consensus guidelines- Developing multidisciplinary expert panels to create national guidelines based on comparative studies and evidence-based research.

- Protocol kits- Developing air embolism response kits for procedure rooms and critical care settings. These kits could include history and symptoms checklists, positioning instructions, oxygenation protocol, HBOT referral center information.

- Decision algorithms- Creating easy to read flowcharts or diagrams to assist providers in immediate bedside decision-making like HBOT initiation, oxygenation, anticoagulation, imaging etc.

- Procedure-specific protocols- Creating tailored protocols for common and uncommon procedures with risk of air embolism for early warning signs and post-procedure monitoring.

- Benchmarking- Allowing hospitals to share management practices using de-identified national data registries, to develop best practices.

Adjunctive treatments:

in cases of venous air embolism but is based on physiology rather than robust evidence from studies. Moreover, this is not used in patients with arterial air embolism, and the patient should be laid in flat supine posture to avoid worsening of cerebral edema, raising concerns about it being universally applicable. Given these limitations, comparative studies are needed to develop clinical guidelines.

Other therapies like lidocaine, steroids and mannitol have been suggested for treatment of air embolism but lack robust data. Therefore, these therapies should only be treated as adjunctive and be tailored to individual patients data is available.

Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) can be used in refractory cases, but its use is limited to special centers and experienced physicians.

Proposed Solutions:

- Comparative studies- Funding comparative studies showing improved outcomes and robust data for developing standardized protocols that can be accepted universally.

- Positioning guidelines- Establishing evidence-based guidelines for patient positioning for various procedures to prevent air embolism.

- Drug registry and monitoring- Creating a drug registry for experimental use of drugs in these cases to collect safety data.

- Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) escalation protocol- Developing algorithms for initiating ECMO in severe cases and train staff regarding the same.

- Review boards- Forming review boards at hospitals to review air embolism cases and offer adjunctive treatment protocols, similar to antibiotic stewardship teams.

In summary, air embolism is a potentially life-threatening condition and can result from common conditions like CVC insertion or removal, neurosurgical procedures or from uncommon causes like endoscopic procedures, barotrauma or cardiac bypass surgery. The clinical picture can be variable depending on the cause, volume, location, route or rate of air entry leading to diagnostic and treatment challenges as it can mimic other medical emergencies. This is further complicated by limited access to advanced therapies and lack of standardization in diagnosis and treatment. These issues can be addressed by increased awareness & education, and evidence-based guidelines to improve outcomes.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None.

Funding Statement: None.

Acknowledgements: None.

References:

- Muth CM, Shank ES. Gas Embolism. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(7):476-482. doi:10.1056/NEJM200002173420706

- Ho AMH, Ling E. Systemic Air Embolism after Lung Trauma. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(2):564-575. doi:10.1097/00000542-199902000-00033

- Muth CM, Shank ES. Gas Embolism. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(7):476-482. doi:10.1056/NEJM200002173420706

- Mitchell SJ. Decompression illness: a comprehensive overview. Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine Journal. 2024;54(1(Suppl)):1-53. doi:10.28920/dhm54.1.suppl.1-53

- Marsh PL, Moore EE, Moore HB, et al. Iatrogenic air embolism: pathoanatomy, thromboinflammation, endotheliopathy, and therapies. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023;14:1230049. doi:10.3389/FIMMU.2023.1230049/XML

- Červeň air embolism: neurologic manifestations, prognosis, and outcome. Frontiers in Neurology. 2024;15:1417006. doi:10.3389/FNEUR.2024.1417006

- Vann RD, Butler FK, Mitchell SJ, Moon RE. Decompression illness. The Lancet. 2011;377(9760):153-164. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61085-9

- OREBAUGH SL. Venous air embolism. Critical Care Medicine. 1992;20(8):1169-1177. doi:10.1097/00003246-199208000-00017

- McCarthy CJ, Behravesh S, Naidu SG, Oklu R. Air Embolism: Diagnosis, Clinical Management and Outcomes. Diagnostics. 2017;7(1):5. doi:10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS7010005

- Vesely TM. Air embolism during insertion of central venous catheters. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2001;12(11):1291-1295. doi:10.1016/S1051-0443(07)61554-1

- Gordy S, Rowell S. Vascular air embolism. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2013;3(1):73. doi:10.4103/2229-5151.109428

- Vesely TM. Air embolism during insertion of central venous catheters. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2001;12(11):1291-1295. doi:10.1016/S1051-0443(07)61554-1

- Palmon SC, Moore LE, Lundberg J, Toung T. Venous air embolism: A review. J Clin Anesth. 1997;9(3):251-257. doi:10.1016/S0952-8180(97)00024-X

- Faberowski LW, Black S, Mickle JP. Incidence of venous air embolism during craniectomy for craniosynostosis repair. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(1):20-23. doi:10.1097/00000542-200001000-00009

- Faberowski LW, Black S, Mickle JP. Incidence of venous air embolism during craniectomy for craniosynostosis repair. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(1):20-23. doi:10.1097/00000542-200001000-00009

- Bithal PK, Pandia MP, Dash HH, Chouhan RS, Mohanty B, Padhy N. Comparative incidence of venous air embolism and associated hypotension in adults and children operated for neurosurgery in the sitting position. European journal of anaesthesiology. 2004;21(7):517-522. doi:10.1017/S0265021504007033

- Khan M, Schmidt DH, Bajwa T, Shalev Y. Coronary air embolism: Incidence, severity, and suggested approaches to treatment. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Diagnosis. 1995;36(4):313-318. doi:10.1002/CCD.1810360406

- Agarwal R, Sinha DP. Coronary Artery Air Embolism. The Journal of invasive cardiology. 2019;31(8):E264.

- Khan M, Schmidt DH, Bajwa T, Shalev Y. Coronary air embolism: Incidence, severity, and suggested approaches to treatment. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1995;36(4):313-318. doi:10.1002/CCD.1810360406

- Hubbard M, Davis FM, Malcolm K, Mitchell SJ. Decompression illness and other injuries in a recreational dive charter operation. Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. 2018;48(4):218-223. doi:10.28920/DHM48.4.218-223

- Hubbard M, Davis FM, Malcolm K, Mitchell SJ. Decompression illness and other injuries in a recreational dive charter operation. Diving Hyperb Med. 2018;48(4):218-223. doi:10.28920/DHM48.4.218-223

- Olaiya B, Adler DG. Air embolism secondary to endoscopy in hospitalized patients: Results from the National Inpatient Sample (1998-2013). Annals of Gastroenterology. 2019;32(5):476-481. doi:10.20524/AOG.2019.0401

- Voigt P, Schob S, Gottschling S, Kahn T, Surov A. Systemic air embolism after endoscopy without vessel injury – A summary of reported cases. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2017;376:93-96. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2017.03.009

- Olaiya B, Adler DG. Air embolism secondary to endoscopy in hospitalized patients: Results from the National Inpatient Sample (1998-2013). Ann Gastroenterol. 2019;32(5):476-481. doi:10.20524/AOG.2019.0401

- Lee JH, Yoon SH, Hong H, Rho JY, Goo JM. Incidence, risk factors, and prognostic indicators of symptomatic air embolism after percutaneous transthoracic lung biopsy: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Eur Radiol. 2020;31(4):2022. doi:10.1007/S00330-020-07372-W

- Lee JH, Yoon SH, Hong H, Rho JY, Goo JM. Incidence, risk factors, and prognostic indicators of symptomatic air embolism after percutaneous transthoracic lung biopsy: a systematic review and pooled analysis. European radiology. 2021;31(4):2022-2033. doi:10.1007/s00330-020-07372-w

- Gursoy S, Duger C, Kaygusuz K, Ozdemir Kol I, Gurelik B, Mimaroglu C. Cerebral arterial air embolism associated with mechanical ventilation and deep tracheal aspiration. Case reports in pulmonology. 2012;2012:416360. doi:10.1155/2012/416360

- Ibrahim AE, Stanwood PL, Freund PR. Pneumothorax and systemic air embolism during positive-pressure ventilation. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(5):1479-1481. doi:10.1097/00000542-199905000-00035

- McCarthy CJ, Behravesh S, Naidu SG, Oklu R. Air Embolism: Diagnosis, Clinical Management and Outcomes. Diagnostics. 2017;7(1):5. doi:10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS7010005

- Schäfer ST, Lindemann J, Brendt P, Kaiser G, Peters J. Intracardiac transvenous echocardiography is superior to both precordial Doppler and transesophageal echocardiography techniques for detecting venous air embolism and catheter-guided air aspiration. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2008;106(1):45-54. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000289646.81433.28

- Mitchell SJ, Bennett MH, Moon RE. Decompression Sickness and Arterial Gas Embolism. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022;386(13):1254-1264. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2116554

- Kihara K, Orihashi K. Investigation of air bubble properties: Relevance to prevention of coronary air embolism during cardiac surgery. Artificial Organs. 2021;45(9):E349-E358. doi:10.1111/AOR.13975

- Boussuges A, Molenat F, Carturan D, Gerbeaux P, Sainty JM. Venous gas embolism: Detection with pulsed Doppler guided by two-dimensional echocardiography. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1999;43(3):328-332. doi:10.1034/J.1399-6576.1999.430314.X

- Stewart DL, Elsayed Y, Fraga MV, et al. Use of Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in the NICU for Diagnostic and Procedural Purposes. Pediatrics. 2022;150(6). doi:10.1542/PEDS.2022-060053

- Liu AZ, Winant AJ, Lu LK, Rameh V, Byun K, Lee EY. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for pulmonary embolus evaluation in children: up-to-date review on practical imaging protocols. Pediatric Radiology. 2023;53(7):1260-1269. doi:10.1007/S00247-022-05451-2

- Tang CX, Schoepf UJ, Chowdhury SM, Fox MA, Zhang LJ, Lu GM. Multidetector computed tomography pulmonary angiography in childhood acute pulmonary embolism. Pediatric Radiology. 2015;45(10):1431-1439. doi:10.1007/S00247-015-3336-6/FIGURES/6

- Jung YC, Kang M, Cho HJ, Chong Y, Lee JW. Point‐of‐Care Ultrasonography Detects Vanishing Air Embolism Following Central Venous Catheter Removal in a Patient With Chest Tube Drainage: A Case Report. Clinical Case Reports. 2025;13(7):e70578. doi:10.1002/CCR3.70578

- Lee MS, Sweetnam-Holmes D, Soffer GP, Harel-Sterling M. Updates on the clinical integration of point-of-care ultrasound in pediatric emergency medicine. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2024;36(3):256-265. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000001340

- Guo JL, Wang HB, Wang H, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography detection of air embolism during endoscopic surgery and validity of hyperbaric oxygen therapy: Case report. Medicine (United States). 2021;100(23):e26304. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000026304

- Runge VM, Heverhagen JT. Diagnostic and Technological Advances in Magnetic Resonance (Focusing on Imaging Technique and the Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media), Computed Tomography (Focusing on Photon Counting CT), and Ultrasound – State of the Art. Investigative Radiology. Published online 2025. doi:10.1097/RLI.0000000000001210

- Sridharan A, Eisenbrey JR, Forsberg F, Lorenz N, Steffgen L, Ntoulia A. Ultrasound contrast agents: microbubbles made simple for the pediatric radiologist. Pediatric Radiology. 2021;51(12):2117-2127. doi:10.1007/S00247-021-05080-1

- Westwood M, Ramaekers B, Grimm S, et al. Software with artificial intelligence-derived algorithms for analysing CT brain scans in people with a suspected acute stroke: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 2024;28(11):1. doi:10.3310/RDPA1487

- Henkin S, Houghton D, Hunsaker A, et al. Artificial Intelligence for Risk Stratification of Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Perspectives on Clinical Needs, Expanding Toolkit, and Pathways Forward. American Journal of Cardiology. 2025;252:40-48. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2025.05.025

- Bojsen JA, Elhakim MT, Graumann O, et al. Artificial intelligence for MRI stroke detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Insights into Imaging. 2024;15(1):1-13. doi:10.1186/S13244-024-01723-7/FIGURES/1

- Abed S, Hergan K, Pfaff J, Dörrenberg J, Brandstetter L, Gradl J. Artificial intelligence for detecting traumatic intracranial haemorrhage with CT: A workflow-oriented implementation. The Neuroradiology Journal. Published online 2025:19714009251346477. doi:10.1177/19714009251346477

- Schummer W, Schummer C, Rose N, Niesen WD, Sakka SG. Mechanical complications and malpositions of central venous cannulations by experienced operators: A prospective study of 1794 catheterizations in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Medicine. 2007;33(6):1055-1059. doi:10.1007/S00134-007-0560-Z

- Muth CM, Shank ES. Gas Embolism. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(7):476-482. doi:10.1056/NEJM200002173420706

- McCarthy CJ, Behravesh S, Naidu SG, Oklu R. Air Embolism: Practical Tips for Prevention and Treatment. J Clin Med. 2016;5(11). doi:10.3390/JCM5110093

- Gordy S, Rowell S. Vascular air embolism. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2013;3(1):73. doi:10.4103/2229-5151.109428

- Mirski MA, Lele AV, Fitzsimmons L, Toung TJK. Diagnosis and treatment of vascular air embolism. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(1):164-177. doi:10.1097/00000542-200701000-00026

- Shaikh N, Ummunisa F. Acute management of vascular air embolism. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma and Shock. 2009;2(3):180. doi:10.4103/0974-2700.55330

- Moon RE. Bubbles in the brain: what to do for arterial gas embolism? Critical care medicine. 2005;33(4):909-910. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000159726.47336.F8

- Stewart TE, Meade MO, Cook DJ, et al. Evaluation of a Ventilation Strategy to Prevent Barotrauma in Patients at High Risk for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(6):355-361. doi:10.1056/NEJM199802053380603

- Moon RE. Hyperbaric treatment of air or gas embolism: current recommendations. Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine. 2019;46(5):673-683. doi:10.22462/10.12.2019.13

- Thom SR. Oxidative stress is fundamental to hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2009;106(3):988-995. doi:10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.91004.2008

- Ahmadi F, Khalatbary A. A review on the neuroprotective effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Medical Gas Research. 2021;11(2):72. doi:10.4103/2045-9912.311498

- Tsangaris A, Alexy T, Kalra R, et al. Overview of Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (VA-ECMO) Support for the Management of Cardiogenic Shock. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2021;8:686558. doi:10.3389/FCVM.2021.686558

- Zhu GW, Li YM, Yue WH, et al. Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for the treatment of obstructive shock caused by venous air embolism: A case report. World Journal of Clinical Cases. 2024;12(19):4016. doi:10.12998/WJCC.V12.I19.4016

- Papamichalis P, Oikonomou KG, Xanthoudaki M, et al. Extracorporeal organ support for critically ill patients: Overcoming the past, achieving the maximum at present, and redefining the future. World Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 2024;13(2):92458. doi:10.5492/WJCCM.V13.I2.92458

- Donepudi S. Air embolism complicating gastrointestinal endoscopy: A systematic review. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;5(8):359. doi:10.4253/wjge.v5.i8.359

- Chuang J, Kuang R, Ramadugu A, et al. Fatal Venous Gas Embolism During Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography After Simultaneous Deployment of 2 Self-Expandable Metallic Stents. ACG Case Reports Journal. 2022;9(10):e00873. doi:10.14309/CRJ.0000000000000873

- Fang Y, Wu J, Wang F, Cheng L, Lu Y, Cao X. Air Embolism during Upper Endoscopy: A Case Report. Clinical Endoscopy. 2019;52(4):365. doi:10.5946/CE.2018.201

- Zakhari N, Castillo M, Torres C. Unusual Cerebral Emboli. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 2016;26(1):147-163. doi:10.1016/J.NIC.2015.09.013/ASSET/7F756317-DDDA-4B51-A3A6-A9D51E4F32D5/MAIN.ASSETS/GR13.SML

- Brito C, Brito C, Graca J, Vilela P. Cerebral Air Embolism: The Importance of Computed Tomography Evaluation. Journal of Medical Cases. 2020;11(12):394-399. doi:10.14740/jmc.v11i12.3583

- Chuang DY, Sundararajan S, Sundararajan VA, Feldman DI, Xiong W. Accidental Air Embolism: An Uncommon Cause of Iatrogenic Stroke. Stroke. 2019;50(7):e183-e186. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025340/ASSET/28C7ADEA-0830-4F98-8BB6-DD9CEC5E0519/ASSETS/IMAGES/LARGE/E183FIG03.JPG

- McCarthy CJ, Behravesh S, Naidu SG, Oklu R. Air Embolism: Practical Tips for Prevention and Treatment. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2016, Vol 5, Page 93. 2016;5(11):93. doi:10.3390/JCM5110093

- Gordy S, Rowell S. Vascular air embolism. International Journal of Critical Illness and Injury Science. 2013;3(1):73. doi:10.4103/2229-5151.109428

- Bessereau J, Genotelle N, Chabbaut C, et al. Long-term outcome of iatrogenic gas embolism. Intensive Care Medicine. 2010;36(7):1180-1187. doi:10.1007/S00134-010-1821-9

- Why Are Fewer Chambers Available for Emergencies? – Divers Alert Network. Accessed July 10, 2025. https://dan.org/alert-diver/article/why-are-fewer-chambers-available-for-emergencies/

- Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Contraindications – PubMed. Accessed July 10, 2025. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32491593/

- Layon AJ. Hyperbaric Oxygen Treatment for Cerebral Air Embolism Where Are the Data? Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1991;66(6):641-646. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(12)60525-4

- Ou Y, Li JQ, Tang R, Ma DN, Liu Y. Case report: A rare but fatal complication of hysteroscopy air embolism during treatment for missed abortion. Frontiers in Medicine. 2024;11:1504884. doi:10.3389/FMED.2024.1504884

- Mathieu D, Marroni A, Kot J. Tenth european consensus conference on hyperbaric medicine: Recommendations for accepted and non-accepted clinical indications and practice of hyperbaric oxygen treatment. Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. 2017;47(1):24-31. doi:10.28920/DHM47.1.24-32

- Lidocaine in the treatment of decompression illness: a review of the literature – PubMed. Accessed July 10, 2025. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12067153/

- Huber S, Rigler B, MäcHler HE, Metzler H, Smolle-Jüttner FM. Successful treatment of massive arterial air embolism during open heart surgery. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2000;69(3):931-933. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(99)01466-6

- Valk AJ, Kanten RA, Oosterheert M. Treating Massive Air Embolism. The Journal of ExtraCorporeal Technology. 1982;14(1):325-327. doi:10.1051/JECT/1982141325

- Redinger, K., Rozin, E., Schiller, T., Zhen, A., & Vos, D. (2022). The Impact of Pop-Up Clinical Electronic Health Record Decision Tools on Ordering Pulmonary Embolism Studies in the Emergency Department. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 62(1), 103-108.