Breakthrough Cancer Pain Management with Fentanyl Opioids

Increasing Expertise in Patient-Centred Breakthrough Cancer Pain Management Using Rapid-Onset Opioids: Focus on Sublingual Fentanyl

Patrizia Romualdi1, Alice Baggi2, Giuseppe Casale3, Mirko Rollo5, Riccardo Torta4, Paolo Bossi6

- MD, University of Brescia, Department of Medical-Surgical Specialties, Radiological Sciences and Public Health, Medical Oncology, ASST-Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy

- MD, Antea Foundation Palliative Care Center, Rome, Italy

- MD, UOC Cure Palliative, Verona, Italy

- MD, Full Professor of Clinical Psychology, Department of Neuroscience-University of Turin, Italy

- MD, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Humanitas University, Milan, Italy – IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital, Milan, Italy

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 April 2025

CITATION: ROMUALDI, Patrizia et al. INCREASING EXPERTISE IN PATIENT-CENTRED BREAKTHROUGH CANCER PAIN MANAGEMENT USING RAPID-ONSET OPIOIDS: FOCUS ON SUBLINGUAL FENTANYL CITRATE. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 4, apr. 2025. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6417>. Date accessed: 18 oct. 2025.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i4.6417

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Cancer pain represents a very frequent symptom in cancer patients; it is one of the factors which most impacts their quality of life, and clinicians often experience issues regarding its management. This study focuses on Breakthrough cancer pain which is defined as a transient episode of severe pain in a context of adequately controlled background pain. It has a higher prevalence in advanced disease and in palliative care settings; however, it is present throughout all phases of cancer treatment and follow-up. It should not be considered as a single entity, as it is classified as spontaneous, incident volitional or incident non-volitional. To allow a proper diagnosis, clinicians may leverage specific useful tools, such as the Breakthrough Pain Assessment Tool, and patient-reported outcome measures, using a patient-centred care approach. Breakthrough cancer pain treatment requires Rapid-Onset Opioids, namely rapid-active fentanyl formulations having an onset of effect of less than 15 minutes and a short duration of effect. There are different Rapid-Onset Opioids with different routes of administrations which clinicians can choose according to patient characteristics and preferences. For instance, sublingual fentanyl citrate has an innovative formulation which provides a very rapid onset of action, approximately 6 minutes, giving rapid pain relief; intranasal Rapid-Onset Opioids could be preferable in patients with mucositis or with xerostomia. Opioid use in background cancer pain and Breakthrough cancer pain are a cornerstone of treatment.

Perspective: In the treatment of cancer patients, pain management is of paramount importance, given its impact on the quality of life. A correct diagnosis of Breakthrough cancer pain and proper framing of the patient suffering from it allows for the best management of this issue by using Rapid-Onset Opioids.

Keywords: breakthrough cancer pain, rapid-onset opioids, patient-centered care, sublingual fentanyl

1. Introduction

Pain is one of the most common and feared symptoms reported by cancer patients, and is probably the problem which most impacts their quality of life.

According to a 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis, overall cancer pain prevalence, regardless of cancer stage, is 44.5%, having a higher prevalence when considering the group of patients with advanced, metastatic, or terminal disease (54.6%) but a not negligible percentage also in earliest setting with curative intent (35.8%). These data showed a decline in the prevalence of pain, and also pain severity, as compared with previous systematic literature reviews; however, the number of cancer patients having this problem remains high.

Breakthrough cancer pain (BTcP) is a transient exacerbation of pain in a context of adequately controlled background pain. It is very common, occurring in 40–80% of cancer patients, and significantly limits patient daily activities.

Breakthrough cancer pain treatment requires fast-acting drugs and can be successfully controlled by Rapid-onset opioids (ROOs). Several ROOs have been developed, having different formulations and routes of administration. Sublingual fentanyl citrate has been developed with an innovative formulation which provides rapid pain relief.

It is essential that clinicians be able to recognise this particular symptom and be aware of its proper management. In fact, a recent systematic literature review showed a mean weighted prevalence score for cancer pain undertreatment of 40.2%, highlighting the inadequacy of cancer pain management in more than a third of patients, having a consequent low impact on improving the quality of life of cancer patients.

The aim of this study was to point out some underlying clinical and pharmacological issues regarding the management of oncologic pain, particularly BTcP, by providing clinicians with some additional tools for the proper management of this problem in daily clinical practice, and to enhance patient well-being.

2. Understanding Breakthrough Cancer Pain

Breakthrough cancer pain is usually defined as “an episode of severe pain that occurs in patients receiving a stable opioid regimen for persistent pain sufficient to provide at least mild sustained analgesia,” even if there is no consensus regarding its definition.

It is a specific entity and should not be confused with physiological background pain variations or end-of-dose effects from which it differs on the basis of the following characteristics:

-

its high intensity, generally ≥7 on a Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) of 0–10,

-

short time between onset and peak of intensity (a few minutes),

-

a short duration (approximately 60 minutes),

-

its potential recurrence during 24 h (3–4 daily episodes in the majority of patients), and

-

non-responsiveness to treatment for background pain, even when the daily dose of medication is increased.

Typically, BTcP episodes can occur 1–4 times in a day, even if one third of patients report more than 4 episodes in a day.

Breakthrough cancer pain is not a single entity; it can be classified into:

-

Spontaneous or Idiopathic: the episode is stimulus independent and not predictable.

-

Incident or Precipitated: the episode is related to an identifiable trigger and is thus predictable.

-

Volitional (brought on by a voluntary act, e.g., walking)

-

Non-volitional (brought on by an involuntary act, e.g., coughing)

-

Procedural (related to a therapeutic intervention, e.g., wound dressing).

-

The pathogenesis of BTcP is probably heterogeneous and has not yet been fully understood. It can be caused by a transient excess of stimuli on an area with an impaired nociceptor threshold, such as the transient involvement of nearby sensitive structures by a neoplastic lesion or a new stimulus not necessarily painful under normal conditions (mechanism of allodynia or hyperalgesia). Another possible mechanism could be an increase in the peripheral sensitisation of tissue terminals due to cancer-induced anatomical-functional alterations.

Moreover, a third possible mechanism involved in BTcP genesis could be the involvement of the so-called “silent” nociceptors, due to the mechanical and chemical stimuli related to cancer lesions, with the consequent hyperstimulation of the central spinal neuron.

When considering the mechanisms of pathological pain in general, there is first a sensitisation of the peripheral nerve fibres with the involvement of many neurotransmitters and related receptors, which not only derive from the neuron, but also from the immune system cells and glial cells.

The second step is central sensitisation. Until approximately 10 years ago, it all seemed to take place at the level of the dorsal root ganglion, thus at the spinal cord level.

Recent findings, however, have also identified areas at the central/cortical level which are fundamental for sensitisation and chronic pain; interestingly, there is an overlap between these, and the areas of gratification and emotion, such as the amygdala, hippocampus, nucleus accumbens (NAc) and striatum, prefrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex.

Unfortunately, the emotional aspect related to pain is still often overlooked when, in fact, it is a particularly important element to be taken into account in the proper management of patients with cancer pain. Moreover, in 2020, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) proposed this revised definition of pain: “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.”

A bio-psycho-social model of pain has recently been proposed; pain is not only a nociceptive and/or inflammatory condition, but a condition in which emotional, affective, and social aspects are fundamental as they greatly influence pain perception and the impact it has on the patient’s quality of life.

Pain, chronic stress, anxiety, and depression affect each other. Depression promotes the appearance of a central sensitisation and reduces the threshold for pain. Pain first facilitates the appearance of demoralisation, and then depression, due to the functional impairment and suffering it causes in the patient. Moreover, the frequency of association between depression and pain involves a shift between the concept of co-morbidity and that of co-pathogenesis, in the sense that depression and pain share common pathogenetic elements (inflammatory, autonomic, neuro-hormonal transmitters, etc.).

Focusing on BTcP, its particular characteristics cause particular psycho-emotional distress. Spontaneous and incident non-volitional BTcPs are not predictable; therefore, patients are frightened by the possibility of having these pain exacerbations at any time, and this limits any activity and their relational life, increasing the patient’s sense of isolation. Awareness that certain actions can cause volitional BTcP leads patients to voluntarily avoid such movements or stimuli which contributes to worsening their quality of life.

Moreover, inadequately controlled BTcP could cause reduction of confidence in medical treatment efficacy and of trust in the doctor with consequent difficulties in the ongoing course of oncologic treatment.

3. The Crucial Role of Accurate Breakthrough Cancer Pain Diagnosis

The first step in the adequate management of patients with BTcP consists of a correct diagnosis. In this regard, one of the main obstacles in clinical practice is the inadequate training of specialists in

oncology, more precisely in the recognition of BTcP, as pointed out by physicians themselves in some surveys.

The rapid evolution of cancer treatment is increasing the complexity of the study of the oncologists, who are more prone to focus on the aspects related to cancer treatment, possibly paying less attention to a granular assessment of some of the symptoms reported by the patient. In addition, the intense rhythms of the majority of outpatient oncology clinics lead to the absence of adequate timeframes for thoroughly investigating patient symptoms, including pain.

Therefore, two of the main interventions required to improve BTcP management in clinical practice should be:

-

The implementation of Healthcare Professional training, and

-

Optimisation of the limited time available for investigating and managing BTcP in the outpatient clinic, by also leveraging other health care professionals specifically trained to assess the nuances of pain in cancer patients.

WHAT TO KNOW IN ORDER TO MAKE A CORRECT DIAGNOSIS OF BREAKTHROUGH CANCER PAIN?

First of all, it is important to keep in mind that although BTcP is more common in patients with advanced cancer, one must also remember that it can occur at any stage of the disease, including early stages.

Moreover, any patient with any type of cancer can have cancer pain and BTcP; however, some specific diagnoses have an increased risk of experiencing BTcP and experiencing it early in the course of their disease: pancreatic, head and neck, lung, and breast cancer. Therefore, oncologists must pay special attention when faced with this type of patient, but they must not underestimate the problem in the case of different diagnoses.

Although the main features of BTcP are those already mentioned (rapid onset, high intensity, limited duration), clinical presentation may be very different from patient to patient, and it is essential to thoroughly investigate all specific features in each specific case.

Firstly, it is important to evaluate the background pain management in order to make a differential diagnosis between BTcP and End-of-Dose pain. The latter typically has a slow and progressive onset in the period antecedent to a planned around-the-clock therapy administration. In this case, background pain is not well controlled; therefore, the prerequisite for BTcP diagnosis is lacking, and the clinician has to improve the baseline pain treatment.

Subsequently, it is crucial to investigate the presence of possible actions that can trigger an Incident BTcP, which could be voluntary actions of the patient (e.g., some movements, swallowing) or some procedures (e.g., wound dressing or daily hygiene). In these cases, BTcP is predictable and should consequently be preventable.

WHAT TO USE IN ORDER TO CORRECTLY DIAGNOSE BREAKTHROUGH CANCER PAIN?

Various BTcP diagnostic tools have been proposed in recent years and have been recommended for use in clinical practice, even though there are no formally validated tools available.

The first, proposed in 1990, is the Breakthrough Pain Questionnaire (BPQ) used in some clinical trials but never validated.

A recent systematic review analysed all the tools available following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Metanalysis) and Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) guidelines in order to make recommendations for the most appropriate assessment tool.

According to this review, the Breakthrough Pain Assessment Tool (BAT) is the only one to have met the criteria necessary for being recommended in both clinical and research settings, even if it was not designated for BTcP diagnosis, but for its

characterisation once the presence of BTcP had already been established.

All the other tools analysed have been defined in these systematic reviews as potentially recommendable but requiring additional assessment.

The Alberta Breakthrough Pain Assessment Tool (ABPAT) was mainly designed for intervention research trials and is too complex for routine clinical practice.

The Italian Questionnaire for Intense Episodic Pain (QUDEI) is the Italian version of the BPQ for which a validation study was published in 2021; however, at the moment, its use in clinical practice is still limited.

Finally, some mobile apps have been developed, but again they have still not been validated.

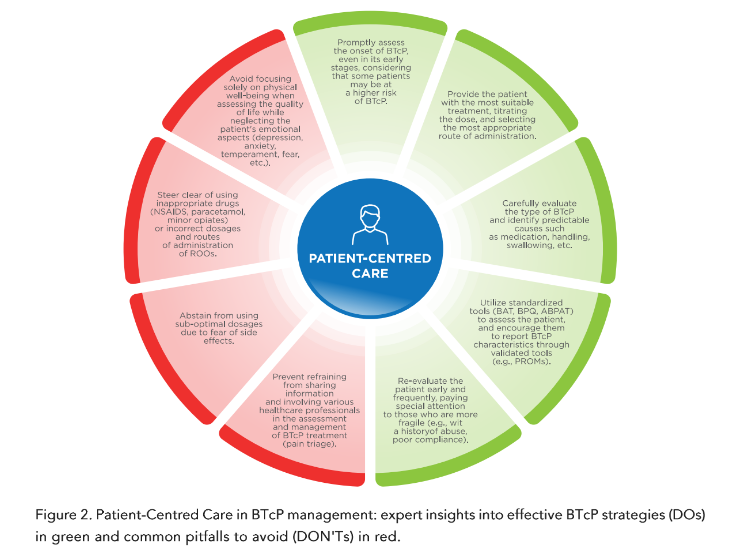

These tools are certainly very useful; however, for the most part, they involve recording BTcP characteristics by the health professional. Today, it is known that a patient-centred care (PCC) approach is the best model in the health care system for providing personalised care and improving patient quality of life. This aspect is even more important if one considers that pain is extremely personal and different for each human being. In fact, patients are the most reliable reporters of their symptoms and health-related quality of life. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are health status reports made by patients without the interpretation of clinicians. Patient-reported outcome data can be collected using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), which are questionnaires or daily diaries administered directly to patients. Thanks to PROMs, communication between patients and health professionals is promoted, and patients are more involved in care and treatment decisions.

Patient-reported outcome measures have also been evaluated in cancer pain assessment in order to complement the other tools briefly described above; a recent review evaluated the validated PROMs used to measure cancer pain. As for the other tools, also in this case, no PROM has a strong recommendation derived from the available evidence; however, one of the most suitable for use could be the Brief Pain Inventory-short form (BPI-SF).

Collecting PROMs and carrying out the other assessment tools certainly takes time which is often insufficient in the oncologic outpatient clinic. One way to make this short time available more efficient could be to create a “pain triage,” where the patient consults with other health professionals, such as trained nurses, before entering the outpatient clinic. The clinician can then, in the short time available, specifically investigate the issues raised during this triage, focusing on the aspects which the patient has been able to report previously.

4. Breakthrough Cancer Pain Treatment:

The Role of Rapid-Onset Opioids and The Characteristics of Each Drug

Background cancer pain requires regular, around-the-clock medication, while for BTcP, the use of supplemental analgesia is necessary. For years, and also nowadays in some centres, oral immediate-release formulations of morphine have been used to treat BTcP. However, their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles (onset of analgesia: 20–30 minutes; peak analgesia: 60–90 minutes; duration of effect: 3–6 hours) are not ideal for controlling BTcP episodes.

Some patients use non-opioid drugs, such as paracetamol or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID); however, these medications also have a time to onset of analgesia of at least 20–30 minutes. Therefore, they are inadequate for the treatment of BTcP and should not be prescribed with this indication (even if they play a role in treating baseline pain). A European observational study reported that patients often use non-pharmacological treatments (acupuncture, aromatherapy, homeopathy, Reiki, and others) while waiting for the effect of the drugs.

Oral immediate-release opioids (typically morphine but also oxycodone or hydromorphone) could be used in the case of procedural BTcP, the onset of which is predictable, and the medication can then be administered to prevent it. Nevertheless, this strategy cannot be applied in the case of idiopathic BTcP for which “on demand” therapy is required.

Fortunately, there is a specific treatment for BTcP, Rapid-Onset Opioids (ROOs), recommended by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines and by the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) guidelines.

Rapid-Onset Opioids are indicated for patients with BTcP whose chronic cancer pain is well controlled by a stable dose of opioids (at least 60 mg of oral morphine per day or its equivalent) for at least 1 week.

Rapid-Onset Opioids have an onset of effect of less than 15 minutes and a short duration of effect — ideal characteristics for BTcP management. The opioid chosen for these rapid-active formulations is fentanyl, owing to its small molecular size and high lipophilicity, which allow it to pass mucosal membranes and enter the bloodstream easily and rapidly. Available ROO formulations include oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate, a fentanyl buccal tablet, an orally disintegrating tablet, fentanyl buccal soluble film, intranasal fentanyl spray and fentanyl pectin nasal spray.

Several placebo-controlled randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated the efficacy of all the transmucosal fentanyl formulations available for BTcP. Importantly, rapid-onset fentanyl has also been associated with a significant improvement in health-related quality of life.

All transmucosal fentanyl formulations play a clinical role in BTcP; however, there is no evidence of the superiority of any particular formulation.

Oral Transmucosal Fentanyl Citrate (OTFC)

Approved in the U.S.A. in 1998 and in Europe in 2002. It is administered in the form of a lollipop and requires the active participation of the patient. Moreover, approximately 75% of the product is swallowed and then absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract; the bioavailability is then approximately 50% of the total dose. The median time of pain relief onset reported is 15 minutes. In addition, some concerns have been raised as to dental problems with prolonged use, due to the sugar content which increases its palatability.

Fentanyl Buccal Tablet (FBT)

Approved in the U.S.A. and in Europe in 2008. Thanks to its technology, it creates an initial decrease in buccal pH, required for its dissolution which occurs in 14–25 minutes, and then an increase in pH which facilitates the permeation of the mucosa. A notable proportion of the fentanyl is absorbed transmucosally; swallowing is minimal, and its bioavailability is better than OTFC. The sublingual area is superior due to its greater salivary flow; however, the FBT also demonstrated adequate absorption in dry areas. The median time to pain relief is 10 minutes.

Fentanyl Buccal Soluble Film (FBSF)

Approved in the U.S.A. in 2009 and in Europe in 2010. Fentanyl is contained in a layer which adheres to the cheek mucosa. The quantity of drug swallowed is minimal. Fentanyl Buccal Soluble Film has demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in pain intensity over a placebo; however, the median time to pain relief has not been reported.

Sublingual Fentanyl (SLF)

Approved in Europe in 2008 and in the U.S.A. in 2011. It is a tablet consisting of water-soluble carrier particles and a mucoadhesive agent to hold the tablet under the tongue. Sublingual fentanyl provides significant improvement in difference in pain intensity and pain relief as compared to a placebo, 10 minutes after its administration.

Intranasal Fentanyl Spray (INFS)

Approved in Europe in 2009, and it is not available in the U.S.A. In a randomised multicentre study, it had a shorter onset of meaningful pain relief as compared to OTFC (median 11 minutes versus 16 minutes). In a systematic review, it was indirectly compared with OTFC, FBT, and oral morphine, showing better improvement in pain relief.

pain intensity difference but without statistical significance. In addition to typical opioid side effects (constipation, nausea/vomiting, and somnolence), in a small percentage of patients, its use was also associated with dysgeusia, dizziness, vertigo, and ulcers of the nasal mucosa.

Fentanyl Pectin Nasal Spray (FPNS)

Approved in Europe in 2010 and in the U.S.A. in 2011. The addition of pectin promotes the formation of a gel which prolongs the residence time of fentanyl at the mucosa, having a better pharmacokinetic profile as compared with non-gelling sprays and having a slower decline in plasma fentanyl levels. Fentanyl Pectin Nasal Spray provides clinically meaningful pain relief within 10 minutes postdose as compared to immediate-release morphine sulfate. In approximately 10% of patients, nasal adverse events, such as mild obstruction and mild nasal discharge, are reported.

Fentanyl Citrate Sublingual Formulation (FCSL)

One of the most recent ROOs sold. It is a tablet which should be placed under the tongue, and it dissolves by itself without chewing or sucking. It has a unique three-layer structure: an external buffering thin layer, fentanyl citrate in the middle, and a neutral core. The initial dissolution of the external buffer layer raises the pH value of the sublingual area; this basic environment causes fentanyl to be at maximum concentration and lipophilicity. It results in an increase in fentanyl absorption and achievement of effective analgesic drug plasma levels. Thanks to this structure, FCSL time to dissolution is 60% shorter than OTFC; it is completely dissolved in 15–20 minutes, and fentanyl is completely absorbed.

The efficacy and safety of FCSL have been evaluated in a prospective, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, crossover study in which it was compared to a placebo. The FCSL significantly improved the sum of pain intensity differences (SPID) at 30 minutes (primary endpoint) but also at each time point from 6 to 60 minutes. Treatment-related adverse events were those typical of opioid therapy with no unexpected toxicity.

Although there are no head-to-head studies between the different ROOs, their efficacy and safety profiles are comparable to each other. Thanks to its fast onset of action (6 minutes) and its lasting pain relief (approximately 60 minutes), FCSL is an effective and reliable option among the other available oral transmucosal fentanyl formulations.

5. Choosing The Optimal Breakthrough Cancer Pain Treatment

A tailored approach is fundamental in BTcP management in order to personalise the treatment regarding both the specific characteristics of the BTcP (onset, predictability, severity, and duration) and the specific characteristics of the patient (underlying disease, prognosis, other oncologic and non-oncologic medications, formulation preferences).

The decisions as to which formulation to choose will most likely be made on the basis of the advantages and disadvantages of the different routes of administration, as head-to-head evaluations of the efficacy of the different ROOs are lacking.

The choice of a ROO should be based on four factors:

-

The characteristics of the BTcP (including duration and time to peak intensity)

-

The characteristics of the drug (attempting to match the pharmacokinetic profile to the patient’s BTcP)

-

Previous responses to opioid therapy (e.g., efficacy and tolerability)

-

The patient’s preference for route of administration.

The first two factors were described in the paragraphs above. When focusing on patient characteristics, many aspects have to be taken into consideration.

Overall, patient condition and prognosis are the starting points. In patients with end-stage cancer, the choice for BTcP treatment is often intravenous morphine, in particular if they are already taking intravenous morphine or have a vascular access device. Rapid-onset opioids are considered for outpatients or for those having a minimum of autonomy in taking medication the absence of a caregiver should be considered, mainly in elderly patients. Older cancer patients are often complex patients due to comorbidities, cognitive decline, altered hepatic and renal functions, and polypharmacy. In general, in this group, the recommendation is “to start slow and go slow,” paying particular attention to ROO titration and monitoring. In cancer patients, polypharmacy is common, making the assessment of potential drug interaction essential.

Inhibitors or inducers of the human cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzyme system (CYP3A4), which metabolises fentanyl, should be avoided and, if this is not possible, patients who use these drugs should be carefully monitored.

Furthermore, the concomitant use of fentanyl and central nervous system (CNS) depressants should be limited, and the concomitant use of fentanyl and partial opioid agonists/antagonists (e.g., buprenorphine, nalbuphine, and pentazocine) should be avoided.

In recent years, a topic under debate regards the possible immune-depressing activity of opioids, thus the potential interference with immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatment; however, this aspect has to be additionally elucidated and, at present, no study confirming this is available.

Another important aspect to evaluate in choosing the best ROO for each patient is the oral and nasal mucosal condition. Cancer patients may not have normal conditions due to cancer disease or oncologic treatments, namely anatomical alterations caused by a neoplastic mass or surgery, and nasal or oral painful mucositis caused by radiotherapy or systemic therapies. Two studies have shown that fentanyl buccal tablet absorption is comparable in patients with or without mucositis or xerostomia; thus, if the patient is able to take oral formulations, theoretically, all ROOs could be used. The case of true difficulties or pain in swallowing is different, as even if sublingual formulations do not require the patient to swallow, the simple act of putting the drug in the mouth often causes a swallowing reflex; these patients typically prefer intranasal fentanyl formulations. A Danish survey identified the primary factors influencing the choice of INFS and OTFC; INFS is preferred in cases of oral dryness or nausea, or for patients dependent on a caregiver who can administer the therapy without the patient’s cooperation. On the other hand, OTFC is preferred in cases of nasal irritation, colds, or other nasal problems.

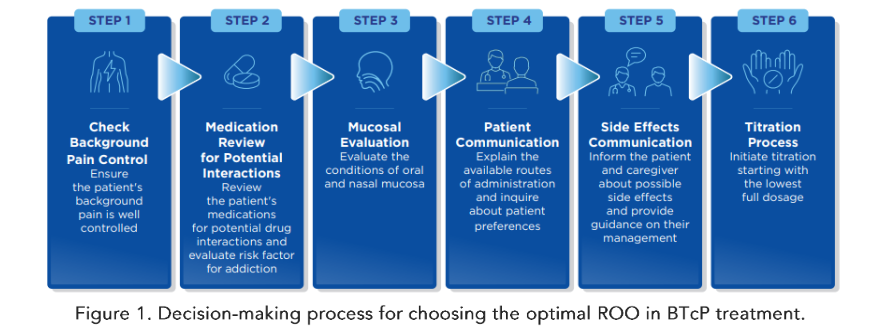

Last but not least, it is essential to be aware of patient preferences regarding the route of administration of the drugs, even if this aspect has been investigated in only a few clinical trials. Patients may be more confident with one or another specific ROO due to their temperament, self-ability, and dexterity in taking medication, life experiences, socio-cultural level, and emotional component related to pain and pain treatment. Making the patient feel comfortable is fundamental in achieving adequate treatment compliance. Figure 1

6. Managing Breakthrough Cancer Pain Treatment With Rapid-Onset Opioids

Once the clinicians have chosen the optimal ROO for that specific patient, it is fundamental to proceed with proper titration of the drug. Some studies have proposed the use of proportional dosing, i.e., the definition of the starting dose of the BTcP treatment considering the dose of the background pain medication. This strategy has shown effectiveness and safeness, even if, according to clinical guidelines, additional evidence is required to routinely recommend this approach. In fact, the majority of titration schedules recommend starting with the lowest full dosage; if the first administration is not effective, a second administration is permitted for each BTcP episode. After the starting dose has been tested, the following doses have to be defined based on the efficacy and tolerability of the first dose; if the pain is well controlled without adverse effects, the same dose should be used for additional episodes. The dose should be increased in the absence of adverse events and in the case of not well-controlled pain, while it should be decreased in the presence of adverse events and well-controlled pain. If the pain is uncontrolled and adverse effects occur, a change in the drug is indicated.

An important consideration when changing a medication for BTcP is the lack of bioequivalence between the different fentanyl formulations; thus, the dose must be titrated specifically for the new formulation in order to avoid side effects. Side effects are the main reason for discontinuing opioids. With an adequate proportional dose or titration, all ROOs may be tolerated with a toxicity profile in line with opioids in general. Patients and their caregivers or relatives must be informed of the potential side effects and educated to recognise them early in order to manage them, thus allowing the treatment to continue without interruption.

One of the most reported side effects is constipation, which is a non-dose dependent effect; it can be prevented and managed with hygiene and diet recommendations as well as the use of peripheral μ-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs). Other possible side effects of opioid drugs are rare when using ROOs as patients are already being treated with a fixed dose of opioids for background pain treatment. In fact, nausea and vomiting are common at the beginning of opioid therapy; anti-emetics are indicated in the first week to prevent them. After the first week, the side effects are typically tolerated, with only initial drowsiness being present.

Respiratory depression is a rare fatal side effect which frightens many clinicians and limits the prescription of opioid drugs. In reality, it is a dangerous side effect in the case of the non-medical use of an elevated dose of opioids used as a recreational drug, while it is a minor problem during the therapeutic use of opioid drugs, and can be well controlled in clinical settings. Specific individualised treatment for BTcP requires not only a correct initial choice of the best ROO formulation for each patient, it is also necessary to regularly reassess the patient in order to evaluate treatment efficacy, increase or decrease treatment intensity if necessary, and also evaluate and manage potential side effects. In addition, it is essential to periodically reassess patient satisfaction and compliance to the treatment. These frequent reassessments are particularly important in very fragile patients (e.g., a previous history of abuse, etc.). The management of BTcP and its treatment requires a multimodal approach. In fact, clinical practice guidelines recommend both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic approaches. In some patients, the relevant emotional and cognitive components which amplify the perception of pain should also be addressed as part of comprehensive care must be addressed. Psycho-neuropharmacological (e.g., dual antidepressants, gabapentinoids) or psychological (e.g., cognitive behavioural therapy, relaxation techniques) interventions may be useful in this regard.

Considering non-pharmacological interventions, patient training and education are very important in order to modulate the way patients interpret pain (e.g., reduce negative expectations regarding the ability to tolerate pain or to have it managed adequately), to provide practice in specific approaches to manage pain (e.g., deep muscle relaxation), and to provide instruction regarding how to use analgesic medications and communicate effectively with clinicians concerning unrelieved pain.

Finally, the treatment of BTcP and of cancer pain in general are not the domain of only oncologists or palliative care physicians; a multidisciplinary approach is needed, with the involvement of all healthcare professionals who manage the diagnosis and treatment of cancer patients. An integration of disciplines and close cooperation between oncologists, surgeons, pathologists, radiologists, palliative care physicians, psychologists, and pain specialists should involve a multidisciplinary psycho-socio-pharmacological approach to cancer pain.

7. Should We Be Afraid of Substance Use Disorder (Addiction) in Breakthrough Cancer Pain Management?

It is well known that the prolonged use of opiates may lead to the development of the phenomenon of psychic dependence, which can be differentiated from tolerance. Psychic dependence is a chronic recurrent disorder characterised by compulsive behaviour, which is the loss of control over both the seeking and the intake of drugs of abuse, regardless of negative consequences to oneself or others. The reinforcing effects of all substances of abuse are due to the actions on the mesocorticolimbic system, a circuit which includes dopaminergic neurons projecting from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the shell of the NAc, to the amygdala, and to the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Endogenous opioids and opiates facilitate the release of dopamine, directly activating the μ and δ receptors in the NAc and indirectly activating the μ receptors on GABAergic neurons in the VTA, where the inhibition of GABAergic neurotransmission increases the firing of dopaminergic neurons.

The release of dopamine into the NAc is associated with both the effects of the substance of abuse, and the environment in which its administration occurs. This hypothesis could explain why opiates and other drugs of abuse produce reinforcement for both positive affective (pleasure, gratification) and negative affective (aversion) experiences and why they may function as discriminative stimuli in operational decisions. A crucial role has been attributed to environmental conditioning factors.

It has been proposed that the development of psychic dependence and the vulnerability to relapse after deprivation are the result of CNS neuroadaptive processes which oppose the reinforcement of drugs of abuse. The long-term effectiveness of the stimuli associated with drugs of abuse in animal models of relapse, leading to compulsive seeking behaviour; in humans, it reflects the continuing responsiveness to conditioned stimuli. This confirms the significant role of learning and conditioning factors of addictive drugs liable for abuse.

The therapeutically appropriate use of opiates for the treatment of chronic pain has been hindered to date by the incorrect belief that their use will inevitably lead to psychic dependence. The actual prevailing hypothesis suggests that the therapeutic use of opiates is not associated with the conditioning environmental stimuli which are so important in determining the positive reinforcement leading to compulsive use. The condition for which the drug is taken, and especially the underlying painful pathology, do not provide the substrate and the context which the patient seeks in taking the drug clinical findings related to pain therapy have confirmed that the phenomenon of abuse is very rarely observed.

Moreover, from the scientific point of view, it is known today that several publications have confirmed that the mechanism of reward leading to compulsive behaviour is inhibited in the mesolimbic system of people having chronic neuropathic pain. In addition, intense chronic pain causes a large quantity of beta-endorphin to be released into the ventral tegmental area, binding the opioid receptors which are on the surface of the dopaminergic neurons which project to the NAc and the prefrontal cortex. Within a few hours, they send the opioid receptors themselves into desensitisation; this does not function and, therefore, the dopamine no longer reaches the NAc, and the gratification circuit is interrupted.

In the past three decades, a terrible opioid epidemic has been an ongoing public health concern in the United States (U.S.); the number of overdose deaths involving opioids has increased yearly since the mid-1990s, causing extensive harm and devastation. This opioid epidemic became a public health crisis which, in part, was fuelled by excessive prescriptions from physicians themselves. At least 4 waves of epidemic occurred, and in the fourth wave, an increase in fentanyl and other synthetic opioids caused related overdose deaths. The opioid epidemic continues to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S.

Some of the factors that contributed to create the opioid epidemic were overprescribing opioid drugs for people affected by acute pain, a lack of pharmacological knowledge, and the lack of adequate control over the unscrupulous and guilty/wild marketing strategies of some pharmaceutical companies, which often pushed to higher performance levels and not for chronic pain therapeutic treatment.

The negative consequences of the epidemic are substantial, leading to increased access to opioids for vulnerable populations, having left millions of people suffering from opioid use disorder due to the over-prescription of highly addictive substances which consequently caused accidental deaths among the addicted population which then had access to heroin or fentanyl.

At the same time, this opioid epidemic resulted in policymakers recommending limitations on prescribing opioids. This led to community pharmacy restrictions which have caused barriers for patients with cancer-related pain attempting to obtain opioid prescriptions to treat their severe pain.

However, as already explained, clinical studies have shown that, when opioids are appropriately used to control chronic pain (oncologic or not), abuse or addiction does not usually occur as the mesocorticolimbic system is not activated. Thus, voluntary use induces compulsive behaviour leading to addiction, while therapeutic use does not create compulsion or addiction.

Therefore, it should be clear that many of the people who died in the U.S. were voluntary users addicted to opioids without needing them, in the same way as thousands of people used them as recreational drugs, becoming drug addicted and dying as abusers.

In Europe, these terrible epidemics have not been seen, perhaps due to more restrictive legislation and more efficient methods of control and containment.

Nevertheless, addiction problems have been reported in 0% to 7.7% of cancer patients, and this percentage may be underestimated. This could happen when cancer patients develop aberrant drug-related behaviour, using opioids in a different way than that recommended by clinicians. Currently, possible predictive factors of opioid addiction in cancer patients are not as yet well known; previous substance abuse, younger age, and lack of an adequate social and familial context have preliminarily indicated a possible correlation with a predisposition to opioid addiction in oncologic patients.

patients. Thus, physicians should not deny a highly effective treatment, such as ROOs, for fear of the risk of addiction, which is very low; however, adequate screening is recommended in order to identify the patients most at risk of aberrant behaviour who should be monitored more closely during treatment. Some risk assessment tools have been developed; however, additional research is needed in this context.

8. Conclusion

More than half of all cancer patients experience BTcP during their cancer history; doctors treating such patients, not only oncologists, should know how to best manage this extremely disabling symptom.

The correct management of BTcP starts with the knowledge of its particular characteristics, an adequate diagnosis, and appropriate framing of the patient. In fact, each cancer patient is unique and requires tailored treatment.

Specific courses focused on the treatment of oncologic pain and BTcP should be periodically reassessed by the medical staff managing the cancer patients, with the aim of providing the essential skills for promptly recognising and best managing these symptoms, without encroaching on the limited time available in outpatient clinics.

Fortunately, once the correct diagnosis of BTcP has been made, there is a specific treatment for this type of disorder: ROOs are rapid-release opioids which allow the pain peak to be controlled within minutes, giving immediate relief to the patient.

Above all, clinicians should not be afraid to use opioid drugs and ROOs in the case of a correct diagnosis of cancer pain and BTcP. Evidence from the literature has shown that the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying chronic pain, and environmental conditioning factors in the case of cancer pain exclude the risk of addiction; therefore, undertreatment of patients suffering from oncologic pain cannot be justified today.

Clinicians then need to know how to choose the best formulation and route of administration for the patient, based on his or her characteristics and the type of BTcP; they need to know how to carry out adequate titration of the drug, and frequent reassessments of the symptoms and treatments.

One should be aware of the differences in ROOs in terms of route of administration, bioavailability, absorbability, quickness of action and duration of activity. This would allow physicians to tailor the treatment of BTcP after an adequate assessment of the patient’s symptoms, and the impact of the pain on quality of life and functionality.

Disclosures

PR, AB, GC, MR, RT and PB participated in an Advisory Board supported by an unrestricted grant from Angelini Pharma. It is important to note that the sponsor played no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of this review. Special thanks to Éthos S.r.l. for their editorial support in coordinating the meeting and providing technical assistance during the finalisation and submission of the manuscript.

This publication was supported by an unrestricted grant from Angelini Pharma.

References

1. Minollo C, Girelli G, Pinato L, et al. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2022;30(7):3095-104.

2. Snijders RAH, Bron L, Theunissen M, van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ. Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients with Cancer 2022: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2022;13(1):39.

3. Van Den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, et al. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: A systematic review of the past 40 years. Annals of Oncology. 2017; 28(1):1437-49.

4. Portenoy RK, Payne D, J. Breakthrough pain: characteristics and impact in patients with cancer. Pain. 1999;81(1-2):124-34.

5. Hsuic S, Imamoto S, Matsic S, Sakulo A. Characteristics and Treatment of Breakthrough Pain (BtCP) in Palliative Care. Med Arch. 2017; 71(4):246-50.

6. Schug SA, Ting S. Formulations in the Management of Breakthrough Pain. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(3):859-70.

7. Kharasch ED, Wittington D, Hofer C. Efficacy and Safety of Fentanyl Buccal Soluble Film in Patients with Cancer in the Presence of Oral Mucositis. J Pain Res. 2014;7:299-307.

8. Finn AJ, Hill WDC, Tagarro I, Gevar LN. Absorption and Tolerability of Fentanyl Buccal Soluble Film (FBSF) in Patients with Cancer in the Presence of Oral Mucositis. J Pain Res. 2011;24:245-51.