Cannabinoid Effects on Memory After Mild TBI in Mice

Cannabinoid Receptor Agonist Affects Murine Contextual Fear Conditioned Memory after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

Anthony M. Farrugia ¹, Brian N. Johnson ², Akiva S. Cohen ¹⁻²

¹ Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

² Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 June 2025

CITATION Farrugia, AM., Johnson, BN., et al., 2025. Cannabinoid Receptor Agonist Affects Murine Contextual Fear Conditioned Memory after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(6). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6613

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6613

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Mild traumatic brain injuries are common and can lead to memory deficits, partly due to hippocampal dysfunction. Mild traumatic brain injury causes a decrease in network excitability in area CA1 of the hippocampus. We have previously demonstrated that applying the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN55,212-2 to injured brain slices, restores action potential firing to levels not significantly different than action potentials recorded in slices from uninjured (sham) animals. Here, we evaluated whether WIN55,212-2 also improves hippocampal-dependent memory in vivo using a contextual fear conditioning paradigm. Mice subjected to lateral fluid percussion injury were treated with WIN55,212-2 at doses of 0.75, 0.25, or 0.1mg/kg. Memory is thought to consist of three components: encoding (conditioning), consolidation, and retrieval (testing). At 0.75mg/kg and 0.25mg/kg, all mice froze significantly more than control mice indicating that mouse locomotion was affected at those doses. At concentrations of 0.1mg/kg we observed that injured and sham mice showed no significant differences in freezing rate compared to control sham mice but froze significantly more than injured controls. When administered at 0.1mg/kg only on conditioning days, we saw a similar effect as when injected on both conditioning and testing days. These results suggest that WIN55,212-2 at 0.1 mg/kg primarily aids memory encoding rather than retrieval. Overall, the study demonstrates that at the 0.1mg/kg dose, WIN55,212-2 can restore hippocampal-dependent memory function in lateral fluid percussion injury mice, providing insights into the potential therapeutic role of cannabinoid receptor agonists in mitigating memory deficits following mild traumatic brain injury.

Keywords:

- Traumatic Brain Injury

- TBI

- Contextual Fear Conditioning

- Memory

- Mouse

- Endocannabinoid

Introduction:

A traumatic brain injury (TBI) occurs when a physical jolt, bump, blow, or penetrating injury to the head results in a change in normal brain function. An estimated 69 million people suffer TBIs annually worldwide, leading to around 2.5 million hospitalizations in the United States alone. TBI severity is graded using the Glasgow Coma Scale, which classifies a TBI as mild, moderate, or severe. Most TBIs are categorized as mild TBIs (mTBIs), making up 70-90% of reported injuries. It can be misleading to describe mTBIs as “mild,” as they can lead to a myriad of clinical symptoms that may persist for months or years post-injury. These symptoms can include confusion, irritability, concentration difficulties, anxiety, as well as emotional lability. Memory deficits are also a distinguishing feature of mTBI symptomatology, where there are disruptions in both working and episodic memory.

It is likely that the memory deficits observed after mTBI result from damage to the hippocampus, as the circuitry of the hippocampus is essential for processing spatial and contextual information. The hippocampus is particularly sensitive to mTBI. To ensure proper and optimal hippocampal function, the necessary delicate balance between excitatory and inhibitory (E/I) neurotransmission must be maintained. An imbalance in E/I function provides one potential explanation for the disruptions in normal hippocampal function following mTBI. We have previously reported disturbances in E/I balance post-mTBI. We have found an increase in network excitability in the dentate gyrus (DG) region of the hippocampus together with larger miniature inhibitory post-synaptic currents in area CA1; both of these findings correlated with deficiencies in hippocampal-dependent memory tasks. Decreased network excitability in area CA1 is supported by reports of an increase in spontaneous inhibitory post-synaptic current frequency and a decrease in spontaneous excitatory post-synaptic current frequency following mTBI. We have further reported a decrease in action potential firing post-mTBI in area CA1. Within area CA1, there exists a network of inhibitory basket cells that modulate the firing of CA1 pyramidal cells. Out of the two types of inhibitory basket cells in area CA1, only the cholecystokinin (CCK)-containing basket cells contain cannabinoid receptors. We believe that these CCK-containing interneurons may be a target for restoring normal excitability in the injured area CA1. When we applied the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN55, 212-2 to brain slices from injured animals, we found that action potential firing was restored to a level not significantly different than in slices from sham animals. While this in vitro finding is promising, it is possible that a discrepancy exists between restoring action potential firing in brain slices from injured animals and restoring hippocampal-involved behavior in injured animals. Thus, here we examine whether WIN55, 212-2 can mitigate contextual fear conditioning memory impairments in injured mice.

Materials and Methods:

ANIMALS:

All experiments were done according to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; Protocol 0694). We used 8-week-old (at the time of injury) male C57BL/6J mice for our experiments. Upon arrival at the animal facility, mice habituated for one week before experimentation.

DRUGS

We tested WIN55, 212-2’s effects on contextual fear response. WIN55, 212-2 (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in a vehicle of ethanol, Kolliphor® EL (synonym: Cremophor® EL; Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.9% saline in a final ratio of 1:1:18 (ethanol: Kolliphor: saline). WIN55, 212-2 was administered via intraperitoneal (IP) injection at three doses: 0.75mg/kg, 0.25mg/kg, and 0.1mg/kg. All injections were done one hour before conditioning and freezing assessment. Placebo experiments injected the vehicle alone at the same volume that cannabinoids were administered (0.3mL).

The sham and injured mice underwent one of four potential treatments: placebo/vehicle injections on both conditioning and freezing assessment days, WIN55,212-2 administration on both conditioning and freezing assessment days, WIN55,212-2 administration on conditioning day alone with a placebo/vehicle injection on the freezing assessment day, and the placebo/vehicle injection on the conditioning day, with WIN55, 212-2 administration on the freezing assessment day.

SURGERY AND LATERAL FLUID PERCUSSION INJURY

To produce in vivo mTBI, we utilized the lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) protocol. Both sham and injured animals underwent craniectomy surgery. Prior to surgery, mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (2.6mg/kg) and xylazine (0.16mg/kg) via IP injection. Animals were then placed in a stereotaxic frame where the surgery took place. Eye lubricant was applied and hair on the top of the skull was removed. An incision was made along the midline of the skull and fascia was gently scraped away to expose the right parietal bone. An ultra-thin 3mm diameter Teflon disk was glued using Vetbond (3M, St. Paul, MN, USA) between lambda and bregma and between the sagittal suture and the lateral ridge over the right hemisphere. The Teflon disk was used to guide a trephine in creating a 3mm-wide craniectomy, and the bone was gently removed from the skull to ensure that the dura remains intact. A modified Luer-lock needle hub (3mm in diameter) was secured above the craniectomy using superglue (Loctite, Düsseldorf, Germany) and dental acrylic (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA). The hub was then filled with saline, and a Luer-lock cap was attached to the hub. Mice recovered on a heating pad until they resumed normal movement. The mice were then returned to their cages and allowed to recover for 24 hours before LFPI.

Mice were anesthetized in a chamber using isoflurane (2% oxygen delivered 500mL/min). The Luer-lock caps were taken off, and the saline was removed from the hub and replenished with new saline, ensuring no air bubbles were present. Once mice reached a respiratory rate of one breath per 2 sec, their Luer-lock hub was attached to the tube on the LFPI device (Department of Biomedical Engineering, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA, and Custom Design and Fabrication, Sanston, VA, USA). Once normal breathing resumed, but before the mice were sensitive to stimulation, the pendulum was released, delivering a 20 msec pulse to the intact dura. A pressure of 1.4-1.6atm was delivered to induce mTBI in all injured mice. Sham mice were also attached to the LFPI device but did not receive a fluid pulse. The mice were detached from the LFPI device, and righting reflex time was recorded. After self-righting, mice were anesthetized again, the hub was removed from the skull, and the wound was sutured.

BEHAVIORAL METHODS

We used contextual fear conditioning to assess hippocampal-involved memory. To conduct this behavioral paradigm, researchers place an animal in a neutral context where it receives a noxious unconditioned stimulus, such as a foot shock, creating a conditioned fear response to the conditioned stimulus (the context). The animal is then returned to the context the next day, where they display conditioned fear responses, e.g., freezing. Freezing rates are then used as a quantitative measurement of an animal’s contextual memory. The hippocampus is vital in successfully performing this behavior, and mTBI is known to reduce freezing rates in mice.

The mice were allowed to recover for one week following surgery in their respective home cages. Before behavior, mice were transferred to a clean cage, which was changed at the end of all behavioral experimentation. To ensure that handling of the mice did not affect fear behavior, we handled mice for five days for three minutes per mouse. The first two days of handling were conducted in the animal holding room under a fume hood, while the last three days of handling were done in our procedure room with 45 minutes of habituation prior to handling. Each mouse was transported to the procedure room in individual containers with a mixture of new/clean bedding and bedding from their cage. The experimenter wore the same gown for the entirety of each behavioral cohort.

On conditioning days, mice were injected with WIN55, 212-2 or the vehicle alone an hour prior to experimentation, mice habituated to the procedure room in their individual containers during that time. The conditioning chamber was cleaned with 10% bleach and 70% ethanol before conditioning and between each mouse to eliminate scents and pheromones from previous mice. Mice were placed singularly in the chamber for a total of 6 minutes. For the first 3 minutes, the mice explored the chamber. At the three-minute, four-minute, and five-minute marks, the mice received a foot shock of 0.7mA. After minute six, the chamber was opened, and the mice freely walked back into their individual containers, where they remained until the end of the conditioning period. After conditioning, the containers housing the mice were returned to the animal holding room, and the mice were placed back in their home cage.

The following day, freezing assessment occurred. Mice were transported to the procedure room as they were the previous day, and mice were injected an hour before testing as on the conditioning days. The chamber was cleaned as previously described. The chamber is designed to eliminate outside visual and audio stimuli; therefore, the mouse can only be monitored via a camera that projects to a computer outside of the chamber. Each mouse was placed in the chamber under the same conditions as the conditioning day for five minutes. The freezing behavior is defined as the cessation of all voluntary movement. The mouse was continually monitored and every five seconds to freezing was assessed. After five minutes, each mouse was placed into a new, clean home cage with their respective cage mates.

DATA AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The freezing rate was recorded as we evaluated each mouse every five seconds for a total of five minutes, meaning that each mouse was assessed a total of 60 times in that duration. The freezing rate is presented as the total number of times the mouse was determined to be freezing, with a maximum freezing rate of 60. Statistical analysis between all treatments was carried out using a multiple comparisons ordinary one-way ANOVA test. We also carried out a Mann-Whitney U test when comparing the freezing rate between injured and sham mice treated with the placebo alone. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all comparisons.

Results:

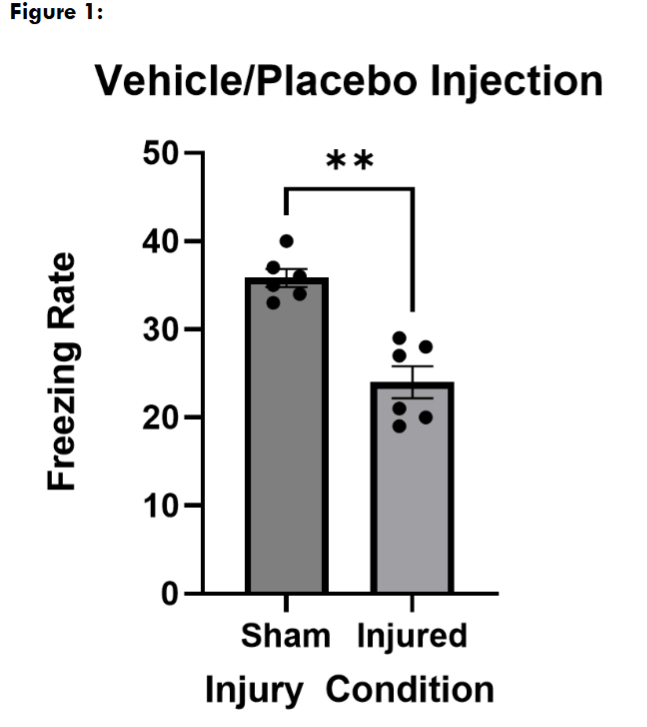

To determine that our mLFPI model had an injury effect on freezing rate, to reproduce the deficiency we have seen previously, and to ensure that the vehicle for our cannabinoid did not significantly affect behavior, we first treated sham and injured mice with the vehicle alone on both conditioning and freezing assessment days. In this placebo/vehicle treated group, we found that mice that received a mLFPI (n = 5) froze significantly less than sham mice (n = 5) where p = 0.0079.

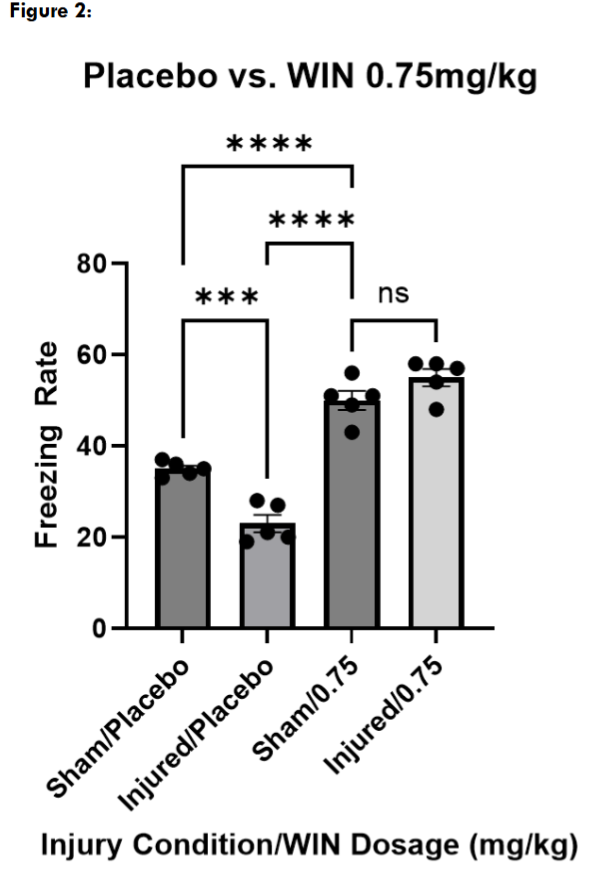

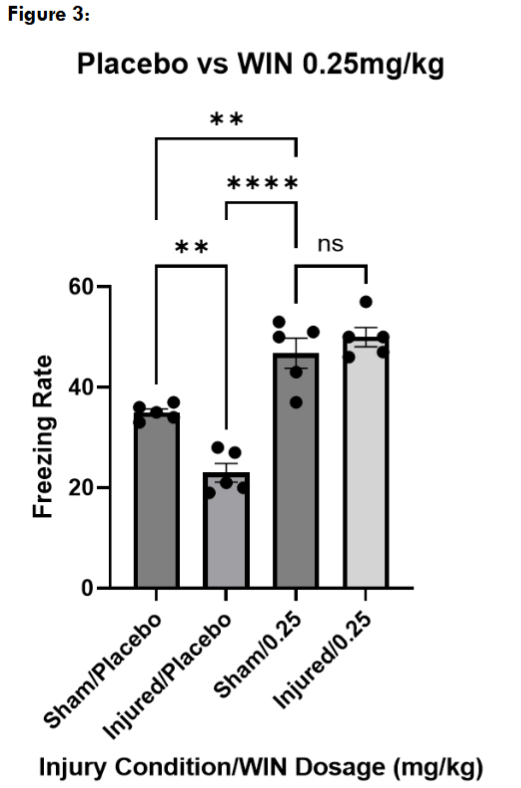

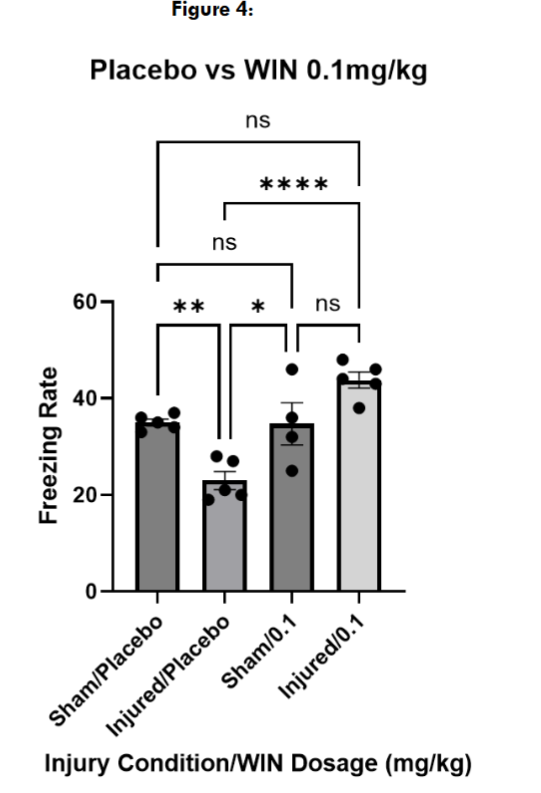

Next, we tested three different doses of WIN55, 212-2, to determine an effective dose for restoring contextual fear memory in injured mice. At 0.75mg/kg and 0.25mg/kg, both injured and sham mice froze significantly more than the placebo-treated sham and injured mice, suggesting a non-specific effect on locomotion. However, injured and sham mice treated with WIN55, 212-2 at 0.1mg/kg froze at levels not significantly different than placebo-treated sham mice.

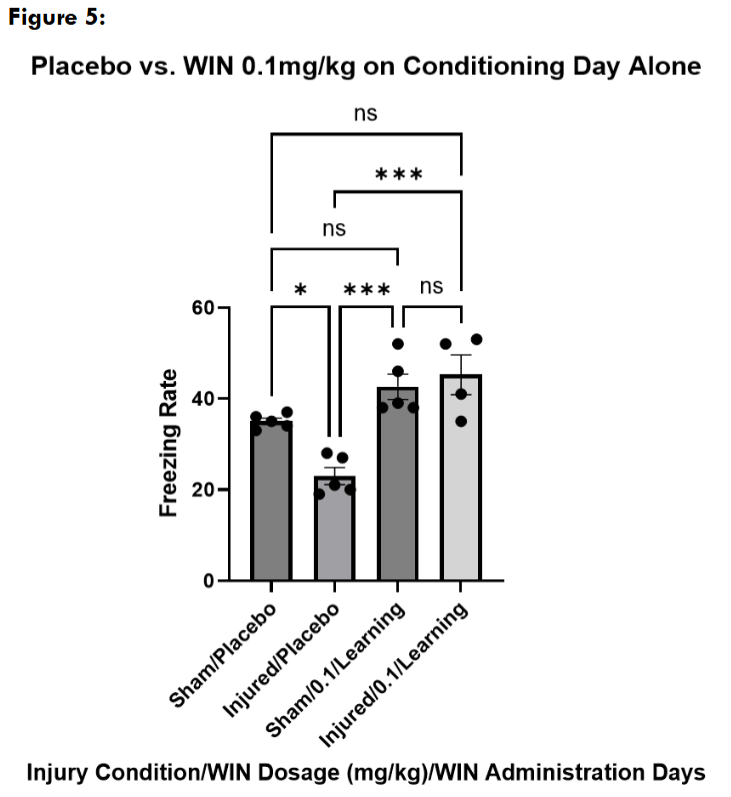

Next, we wanted to explore if the changes we saw with WIN55, 212-2 administration at 0.1mg/kg could be replicated if the mice received a single administration on either the conditioning or the freezing assessment day alone. Mice received a placebo injection of the cannabinoid vehicle on the day they were not being administered with WIN55, 212-2. We found that sham and injured mice treated with WIN55, 212-2 on the conditioning day alone froze at levels not significantly different from sham placebo-treated mice on the testing day, and significantly higher than injured placebo-treated mice.

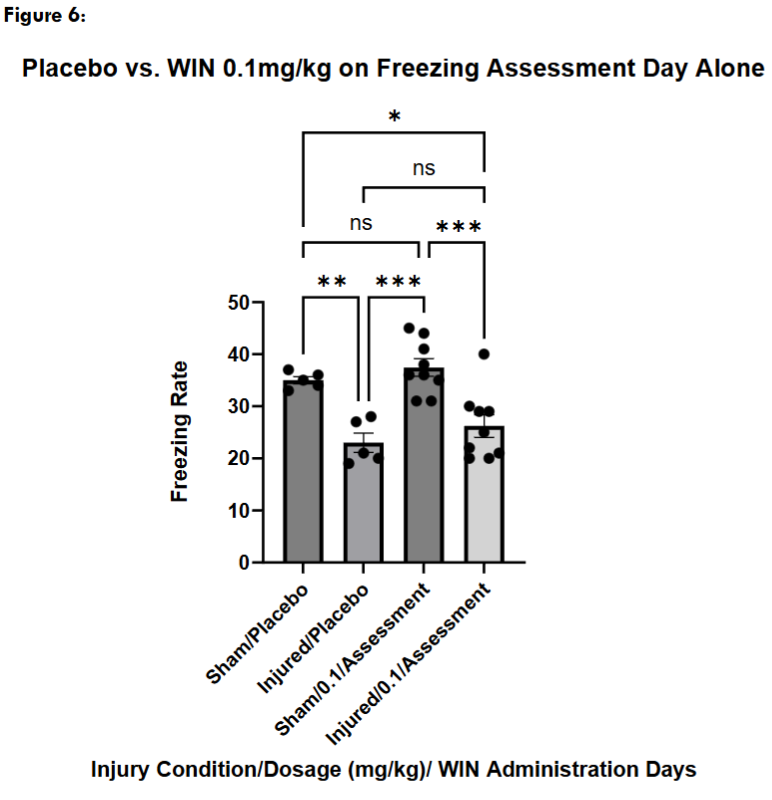

Next, we administered a placebo injection on the conditioning day with a WIN55, 212-2 injection only on the freezing assessment day. Sham mice treated with WIN55, 212-2 on the freezing assessment day alone did not freeze significantly differently than sham placebo mice, while they froze significantly more than injured placebo-treated mice. Injured mice who received a WIN55, 212-2 administration on the freezing assessment day alone did not freeze significantly differently than injured placebo-treated mice but froze significantly less than sham placebo-treated mice.

Discussion:

Prior to this study, we demonstrated that WIN55, 212-2 was able to restore evoked action potential firing in CA1 pyramidal neurons of hippocampal in slices from injured mice to levels not significantly different than what was found in slices from sham animals. However, it is possible for this in vitro restoration in CA1 output function to not translate into restoring normal behavior in injured mice. Thus, our above experiments were necessary in further testing our hypothesis that the endocannabinoid system can be utilized in vivo to restore hippocampal-based memory deficits after mTBI.

Freezing behavior is commonly used to examine hippocampal-involved spatial memory in contextual fear conditioning experiments. Damage or injury to the hippocampus is well-known to produce a reduction in freezing behavior. Because we used freezing, we needed to ensure that our treatment (WIN55, 212-2) did not significantly affect locomotor behavior at our various administrative doses. Various studies have previously investigated that exact question utilizing the open field test, with conflicting reports. One study reported a dose-dependent effect where as little as 0.05mg/kg significantly impacted locomotion in mice. While other studies list doses as high as 1.0mg/kg, 0.75mg/kg, or 0.1mg/kg as not affecting locomotion in open field tests. At our two highest doses, we saw that mice froze significantly more than our placebo-treated controls. We could not say then that locomotion was not affected by WIN55, 212-2 at those doses, however we saw no qualitative behavioral signs of ambulatory difficulties in these mice. Upon the return of these mice to their home cages post-experiment we observed no alterations and they appeared to behave completely normally. Therefore, the mice at the higher doses may have performed better than untreated mice, but further research into WIN55, 212-2’s effect on locomotor activity would be needed to confirm this.

It is widely known that exogenous cannabinoids derived from the Cannabis sativa plant are used to influence the endocannabinoid system; Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) being one that is frequently used both in research and public recreational consumption. Like WIN55, 212-2, THC is also an agonist at CB1 and CB2 receptors, and there are reports that THC can be used to inhibit GABA release via presynaptic CB1Rs within the hippocampus. This mechanism is one potential target for restoring normal E/I balance after mTBI, and is our hypothetical explanation for how WIN55, 212-2 can restore action potential firing and behavioral function to an injured hippocampus. Given the similarity in cannabinoid signaling between WIN55, 212-2 and THC, perhaps THC could also show similar effects in restoring hippocampal function post-mTBI.

It is noteworthy that we only used male mice in this study, especially considering that mTBI leads to differences in patient outcomes between male and female humans. In a review of clinical data, the largest reported fraction of epidemiological data showed that around 47% of human studies reported that women have worse outcomes than men after TBI, although the incidence of TBI is far greater in men. Some estimates as high as 93-95% of animal studies do not include sex as a variable. It has also been reported that male and female mice show differences in vulnerability to memory deficits following mild LFPI, although male mice displayed more drastic memory deficiencies. Our study aimed to investigate how mTBI-induced anterograde amnesia may be affected by a potential therapeutic. Future experiments should include female mice to better understand the biological basis of their relative resilience to mTBI-induced anterograde memory deficits, as well as to ensure that potential therapeutics (like our CB1R agonist) are clinically translatable to both male and female mTBI patients.

Conclusion:

In this study, we demonstrated that at 0.1mg/kg, WIN55, 212-2 can restore hippocampal-involved memory behavior of injured mice to levels not significantly different than control sham mice. Not only did we see an improvement in freezing rates in injured mice when injected at 0.1mg/kg before both conditioning (encoding) and freezing assessment (retrieval) periods, but we also saw that administration only before conditioning was sufficient to restore this behavior to control sham levels. Additionally, when injured mice were treated at 0.1mg/kg on the freezing assessment day alone, we could not show a significant difference compared to injured control mice. These results suggest that if appropriate encoding occurs, then the fear memory can be retrieved successfully. These results agree with our earlier finding of an increase in inhibition from cannabinoid sensitive inhibitory neurons in the hippocampus after LFPI, and raise the possibility that countering this increase in inhibition may be the mechanism by which WIN55, 212-2 exerts its positive effect on memory. Perhaps the deleterious memory effects we see with mLFPI are due to a failure in learning rather than recall. These findings add further evidence to the hypothesis that manipulation of the cannabinoid system may be beneficial for restoring normal hippocampal function post-injury. Understanding the dynamics between hippocampal function, memory, and mTBI may pave the way for therapeutics that target the learning and memory deficits seen after a mTBI.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention., National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. Traumatic Brain Injury In the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.; 2015.

- Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, et al. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2018;130(4):1080-1097. doi:10.3171/2017.10.JNS17352

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance Report of Traumatic Brain Injury-related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths. In: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2014. Accessed July 29, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/get_the_facts.html

- Mckee AC, Daneshvar DH. The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury. Handb Clin Neurol. 2015;127:45-66. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52892-6.00004-0

- Holm L, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Borg J, Neurotrauma Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury of the WHO Collaborating Centre. Summary of the WHO collaborating centre for neurotrauma task force on mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(3):137-141. doi:10.1080/16501970510027321

- McMahon P, Hricik A, Yue JK, et al. Symptomatology and functional outcome in mild traumatic brain injury: results from the prospective TRACK-TBI study. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31(1):26-33. doi:10.1089/neu.2013.2984

- Polinder S, Cnossen MC, Real RGL, et al. A Multidimensional Approach to Post-concussion Symptoms in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Neurol. 2018;9:1113. doi:10.3389/fneur.2018.01113

- Kumar S, Rao SL, Chandramouli BA, Pillai SV. Reduction of functional brain connectivity in mild traumatic brain injury during working memory. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(5):665-675. doi:10.1089/neu.2008.0644

- Nguyen R, Venkatesan S, Binko M, et al. Cholecystokinin-Expressing Interneurons of the Medial Prefrontal Cortex Mediate Working Memory Retrieval. J Neurosci. 2020;40(11):2314-2331. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1919-19.2020

- Pang EW, Dunkley BT, Doesburg SM, da Costa L, Taylor MJ. Reduced brain connectivity and mental flexibility in mild traumatic brain injury. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3(2):124-131. doi:10.1002/acn3.280

- Tayim FM, Flashman LA, Wright MJ, Roth RM, McAllister TW. Recovery of episodic memory subprocesses in mild and complicated mild traumatic brain injury at 1 and 12 months post injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2016;38(9):1005-1014. doi:10.1080/13803395.2016.1182968

- Bartsch T, Döhring J, Rohr A, Jansen O, Deuschl G. CA1 neurons in the human hippocampus are critical for autobiographical memory, mental time travel, and autonoetic consciousness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(42):17562-17567. doi:10.1073/pnas.1110266108

- Smith DM, Mizumori SJY. Hippocampal place cells, context, and episodic memory. Hippocampus. 2006;16(9):716-729. doi:10.1002/hipo.20208

- Squire LR. Memory and the hippocampus: a synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys, and humans. Psychol Rev. 1992;99(2):195-231. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.99.2.195

- Marschner L, Schreurs A, Lechat B, et al. Single mild traumatic brain injury results in transiently impaired spatial long-term memory and altered search strategies. Behav Brain Res. 2019;365:222-230. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2018.02.040

- Agrawal D, Gowda NK, Bal CS, Pant M, Mahapatra AK. Is medial temporal injury responsible for pediatric postconcussion syndrome? A prospective controlled study with single-photon emission computerized tomography. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(2 Suppl):167-171. doi:10.3171/jns.2005.102.2.0167

- McAllister TW. Neurobiological consequences of traumatic brain injury. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(3):287-300. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.2/tmcallister

- Folweiler KA, Samuel S, Metheny HE, Cohen AS. Diminished Dentate Gyrus Filtering of Cortical Input Leads to Enhanced Area Ca3 Excitability after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(11):1304-1317. doi:10.1089/neu.2017.5350

- Witgen BM, Lifshitz J, Smith ML, et al. Regional hippocampal alteration associated with cognitive deficit following experimental brain injury: a systems, network and cellular evaluation. Neuroscience. 2005;133(1):1-15. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.052

- Langlois LD, Selvaraj P, Simmons SC, Gouty S, Zhang Y, Nugent FS. Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury induces persistent alterations in spontaneous synaptic activity of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. IBRO Neuroscience Reports. 2022;12:157-162. doi:10.1016/j.ibneur.2022.02.002

- Johnson BN, Palmer CP, Bourgeois EB, Elkind JA, Putnam BJ, Cohen AS. Augmented Inhibition from Cannabinoid-Sensitive Interneurons Diminishes CA1 Output after Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:435. doi:10.3389/fncel.2014.00435

- Klausberger T, Somogyi P. Neuronal diversity and temporal dynamics: the unity of hippocampal circuit operations. Science. 2008;321(5885):53-57. doi:10.1126/science.1149381

- Grieco SF, Johnston KG, Gao P, et al. Anatomical and molecular characterization of parvalbumin-cholecystokinin co-expressing inhibitory interneurons: implications for neuropsychiatric conditions. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(12):5293-5308. doi:10.1038/s41380-023-02153-5

- Dudok B, Klein PM, Hwaun E, et al. Alternating sources of perisomatic inhibition during behavior. Neuron. 2021;109(6):997-1012.e9. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2021.01.003

- Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106(2):274-285. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.106.2.274

- Yu J, Naoi T, Sakaguchi M. Fear generalization immediately after contextual fear memory consolidation in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;558:102-106. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.04.072

- Omran GA, Abd Allah ESH, Mohammed SA, El Shehaby DM. Behavioral, biochemical and histopathological toxic profiles induced by sub-chronic cannabimimetic WIN55, 212-2 administration in mice. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2023;24(1):8. doi:10.1186/s40360-023-00644-3

- Galanopoulos A, Polissidis A, Georgiadou G, et al. WIN55,212-2 impairs non-associative recognition and spatial memory in rats via CB1 receptor stimulation. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;124:58-66. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2014.05.014

- Mizuno I, Matsuda S, Tohyama S, Mizutani A. The role of the cannabinoid system in fear memory and extinction in male and female mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2022;138:105688. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105688

- Pamplona FA, Prediger RDS, Pandolfo P, Takahashi RN. The cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 facilitates the extinction of contextual fear memory and spatial memory in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;188(4):641-649. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0514-0

- Laaris N, Good CH, Lupica CR. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol is a full agonist at CB1 receptors on GABA neuron axon terminals in the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59(1-2):121-127. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.04.013

- Gupte R, Brooks W, Vukas R, Pierce J, Harris J. Sex differences in traumatic brain injury: what we know and what we should know. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(22):3063-3091. doi:10.1089/neu.2018.6171

- Späni CB, Braun DJ, Van Eldik LJ. Sex-related responses after traumatic brain injury: Considerations for preclinical modeling. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2018;50:52-66. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.03.006

- Fitzgerald J, Houle S, Cotter C, et al. Lateral Fluid Percussion Injury Causes Sex-Specific Deficits in Anterograde but Not Retrograde Memory. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022;16:806598. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2022.806598