Community Strategies for Obstetric Fistula Elimination

Obstetric Fistula in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Comprehensive Review of Community-Based Strategies for Elimination

Oluwasomidoyin O. Bello ¹, Olatunji O. Lawal ¹

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 June 2025

CITATION: Bello, OO., and Lawal, OO., 2025 Obstetric Fistula in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Comprehensive Review of Community-Based Strategies for Elimination. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(6). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6668

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6668

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Obstetric fistula is a devastating childbearing injury that results from poorly managed prolonged obstructed labour without timely surgical intervention. The effects of this injury are long-lasting, and profound as the women become incontinent and marginalized from their communities. While clinical interventions such as conservative care and surgical repair, remain central to its treatment and prevention, community-based initiatives play a critical yet underutilised role in addressing the broader social and structural determinants of obstetric fistula. This review explores the community-based support initiatives focusing on strategies in promoting early identification, recovery, reintegration, and long-term prevention of obstetric fistula. These community-driven approaches not only impact the health of fistula survivors but also contribute to community empowerment and transformation of sociocultural norms in eliminating obstetric fistula. Key community-based interventions include educational programs, stigma reduction efforts, empowering fistula survivors as advocates, and engaging community and religious leaders to enhance awareness and care-seeking behaviour. To effectively eliminate obstetric fistula and restore dignity to affected women, a multi-sectoral, context-specific strategy that integrates medical care with community-driven psychosocial and advocacy interventions is essential to improve quality of life to fistula survivors.

Keywords

obstetric fistula, community-based initiatives, prevention, elimination

Introduction

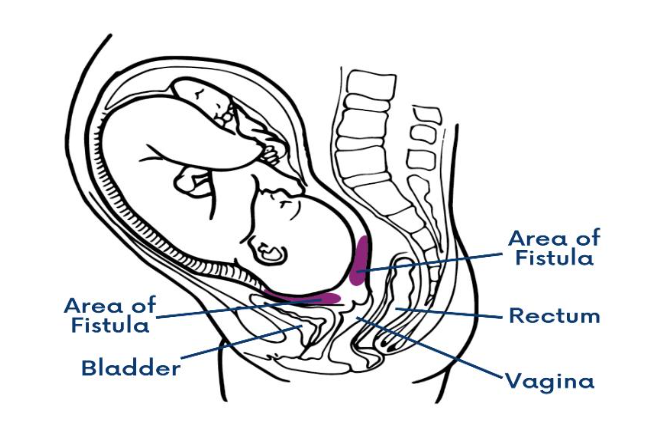

Obstetric fistula (OF) remains one of the most devastating childbirth-related injuries that usually arises from prolonged labour or obstructed delivery, particularly when a caesarean section is unavailable or delayed, thereby causing ischemia and necrosis in pelvic soft tissue, often leading to incontinence, where urine and in some cases, faeces leak uncontrollably through the vagina (Fig 1). Obstetric fistula continues to pose a public health challenge in Sub-Saharan Africa, and despite its devastating impact, it is estimated that only 1 in 50 women with fistula will ever receive treatment. Addressing OF requires a multifaceted approach that integrates both clinical interventions and community-based support initiatives. Clinical interventions, particularly surgical repair of the fistula, play a crucial role in restoring continence and improving the physical health of affected women. However, surgical intervention alone is insufficient to fully address the multifaceted (emotional, social, and economic) needs of women living with fistula. Community-based support initiatives are essential for creating a supportive environment, reducing stigma, and empowering women to reintegrate into their communities. Increasing evidence highlights the effectiveness and cost-efficient strategy of community-led interventions in improving both psychosocial outcomes and access to timely medical care for fistula survivors. These initiatives have demonstrated success in prevention, awareness-raising, and reintegration support within high-burden, low-resource settings. Effective implementation of these initiatives generally involves conducting thorough community health needs assessment, engaging key stakeholders, establishing clear goals, and developing a strategic action plan because health is influenced by social and economic development. These initiatives encompass educational programs, economic empowerment opportunities, psychosocial counselling, and advocacy efforts aimed at restoring and reintegrating OF survivors, while preventing future cases. The integration of clinical and community-based approaches is crucial for holistic care and ensuring long-term positive outcomes for women affected by OF. While key global partners, including World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), United Nations (UN), International Society of Obstetric Fistula Surgeons (ISOFS), and International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), have prioritized the eradication of obstetric fistula as part of the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, a clear understanding of the existing evidence is daunting. Most of the affected countries are yet to implement valuable systematic and sustainable actions to address the multiple systems currently failing so many women. To advance from the treatment efforts toward eradication and improve recovery of women with OF, each fistula-affected country must develop cost-effective and time-bound initiatives that integrate both clinical and community-based interventions. These initiatives will not only improve access to quality care but also address the social, economic, and gender-based factors that contribute to the persistence of OF. Community-based support programs will enhance prevention and treatment efforts by empowering women and girls, and fostering environments that combat stigma and promote reintegration. This review focuses on the community support-based initiatives and strategies aimed at improving the recovery of women with OF and achieving its elimination.

Methods

A comprehensive search strategy was conducted using relevant keywords across four electronic databases – PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and Google Scholar, to identify publications related to community-based initiatives addressing obstetric fistula in Sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2025. Additional sources were identified through manual searching, including official documents and grey literature from websites of relevant organisations such as FIGO, EngenderHealth, FistulaCare, Fistula Foundation, and the World Health Organisation to capture a broad range of perspectives on the subject matter. A selective and purposive approach was also used to identify studies, program evaluations, and national strategies that reflect community-based support OF care initiatives. Search terms used included: “obstetric fistula”, “vesicovaginal fistula”, “community initiatives,” “Sub-Saharan Africa,” “psychosocial support”, “economic support”, “rehabilitation”, “reintegration”, “elimination strategies”, and “barriers to implementing and/or effective community-based initiatives”. Variations of these keywords were applied across different databases to maximise relevant results. Articles were included if they contributed to at least one of the following thematic areas: community awareness and education, community engagement and reintegration, psychosocial support, economic support, capacity building, or national policy and strategic frameworks for OF prevention and elimination. Abstracts of potentially relevant articles were screened for eligibility based on specific criteria such as relevance to the topic, publication in English, and availability of substantial information. Full-text articles that met these criteria were then thoroughly reviewed. The data were extracted and then analysed using narrative synthesis.

Epidemiology, prevalence, and burden of Obstetric Fistula

Obstetric fistula is a neglected public health and social justice issue and remains one of the most distressing consequences of prolonged obstructed labor. Although it has largely been eradicated in developed countries, it is still prevalent in low resource settings and limited information exists about its epidemiology and burden. The true prevalence of obstetric fistula is underestimated because many of the survivors suffer in silence and the challenges associated with tracking obstetric outcomes in low resource settings. It is estimated that over 2 million women live with untreated OF in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. In Sub-Saharan Africa, an estimated 30,000 to 130,000 new cases are added each year, further contributing to the global burden of this preventable condition. Obstetric fistula imposes a substantial physical burden on affected women, compromising health, restricting daily functioning, and contributing to long-term disability. This range of physical complications extends beyond the fistula itself and has a profound impact on women’s overall well-being. Moreover, the burden of OF extends far beyond physical health, profoundly affecting the social, economic, and mental well-being of women and contributing to poor maternal health outcomes. The condition is often associated with shame and blame, causing the victims to experience discrimination and segregation from their families and communities. Such social stigmatization makes it difficult for the women to care for their children or seek treatment, thus the condition may also have greater implications for women’s families and communities. Despite this, there is low prevalence of its awareness among women of reproductive age with rate ranging from 12.8% in Gambia to 61.1% in Tanzania and an average of 40.85% in Sub-Saharan African countries. Prevention and treatment of OF require concerted efforts to raise awareness and improve access to high-quality maternal healthcare services. From a community perspective, understanding and having the knowledge of the risk factors for OF (which are mostly preventable or avoidable) should inform targeted prevention strategies both at the community and health facility.

Strategic framework for elimination of obstetric fistula

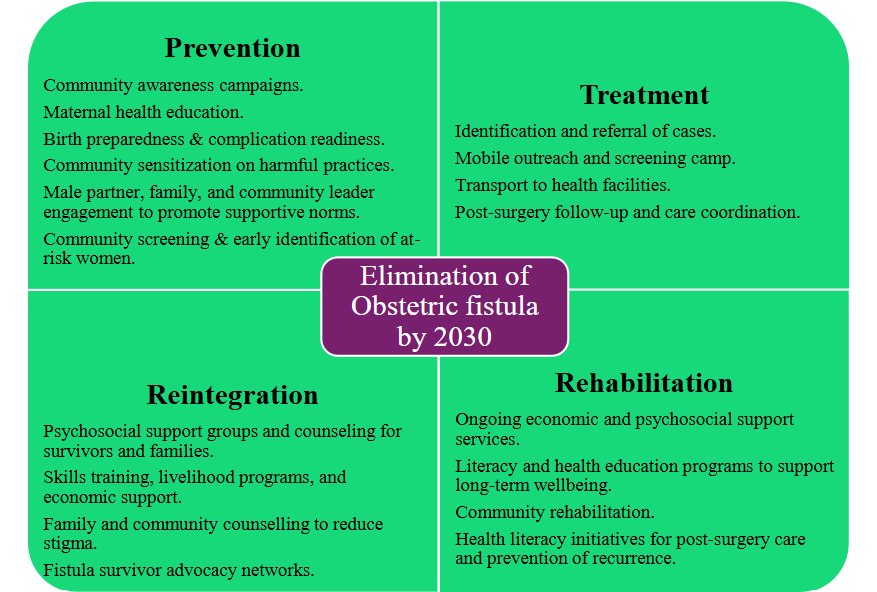

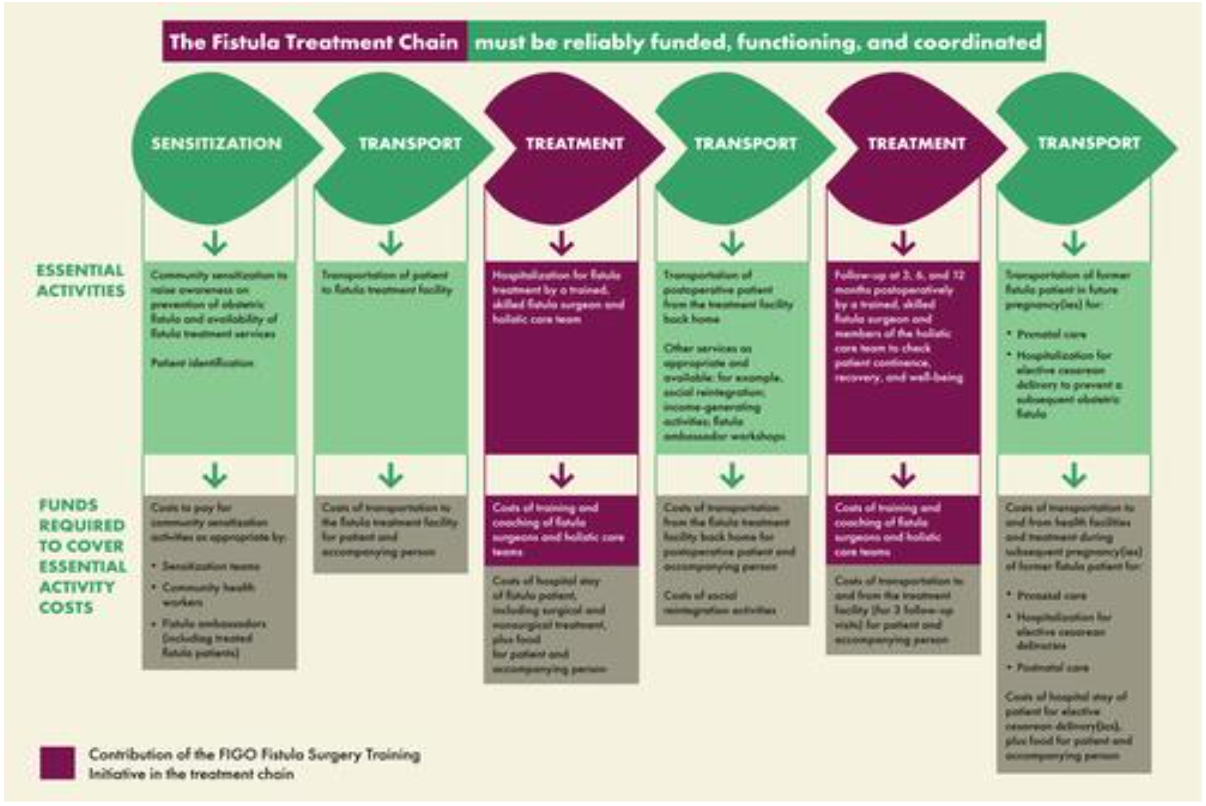

The strategic framework promotes a holistic approach to obstetric fistula care, addressing prevention, treatment, reintegration, and rehabilitation across the continuum of care. Within this framework, prevention is categorized as primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention strategies, each targeting specific stage of maternal health intervention. The primary prevention focuses on health promotion and education principles designed to ensure that all women, their families, and communities understand the need for delaying the age of first pregnancy, accessing, and utilizing family planning, and the advantages of birth spacing. Secondary prevention emphasizes the need to ensure that women have skilled birth attendants present during childbirth and timely access to comprehensive obstetric care services should the need arise. Tertiary prevention seeks to detect and avert the development of fistula in women at risk during labour or in the immediate postpartum period. These prevention strategies are built into the national, regional, and local implementation framework and should be tailored to the specific needs of each country to ensure effective execution and long-term success. In addition, the WHO developed a comprehensive strategic approach that address prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and reintegration. In collaboration with United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and UNFPA, critical interventions of Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (EmONC) were identified. These were classified into Basic and Comprehensive EmONC levels. Basic EmONC includes parenteral administration of antibiotics, uterotonic drugs, anticonvulsants, manual removal of placenta, removal of retained products, assisted vaginal delivery, and neonatal resuscitation. Comprehensive EmONC incorporates the basic services in addition to caesarean sections and blood transfusions. In line with these efforts, FIGO also launched a global initiative focused on the prevention and treatment of fistula, emphasizing capacity-building among healthcare providers, and supporting coordinated efforts to improve fistula prevention and treatment services at all levels. At the regional level, the Economic Community of West African States launched a coordinated initiative “Repair, Reinstate, and Restore,” which was implemented in eight countries: Ghana, Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Nigeria, and Togo. This program aimed to improve access to health and socioeconomic services for all women affected by OF, enabling them to live a productive and dignified lives. In East Africa, efforts to expand support for fistula survivors have included targeted initiatives in Uganda and Tanzania. These programs sought to reduce the medical, social, and economic hardships faced by women living with fistula by integrating best practices and tailoring interventions to local communities across three key areas: restorative surgery, psychosocial support, and livelihood opportunities, all with the goal of improving recovery outcomes and reintegration of OF survivors into the society.

[Reproduced from Slinger, G., & Trautvetter, L. (2020). Addressing the Fistula Treatment Gap and Rising to the 2030 Challenge. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 148(Suppl. 1):9 – 15, Fig. 2, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13033, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)].

| Author & Year | Country | Objectives | Study Design | Type of CBI | Findings | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohammad, 2007 | Nigeria | To improve the social, economic, and health status of women with fistula | Cross-sectional study | Surgical repair, rehabilitation, and skill development for survivors | Increased awareness on health and rights; women integrated into community development programs. | Appropriate interventions and supportive environments help restore mental and physical health. |

| Fiander et al., 2013 | Tanzania | To transport patients to Comprehensive Community-Based Rehabilitation. | Retrospective & Prospective | Mobile fund transfer for transport | TransportMYPatient accounted for 49% of total fistula repairs, reaching 166 patients from most regions in Tanzania | Improved transportation addressed a major healthcare access barrier. |

| Mohamed & Pollaczek, 2018 | Kenya | To expand access to care and build national fistula treatment and outreach capacity | Program report | Action on Fistula (AOF) – extensive community outreach | Over 85% of treated patients accessed care via outreach efforts; long-term outcomes assessed through follow-up | Follow-up was effective in monitoring continence, psychosocial well-being, and economic recovery |

| Delamou et al., 2021 | Guinea | To document medical and reintegration process of fistula survivors. | Qualitative | Social immersion | Women and stakeholders reported positive experiences; higher satisfaction among continent women post-repair | Successful repair followed by social immersion improved quality of life. |

| Pollaczek et al., 2022 | Kenya | To increase access to timely, quality treatment and comprehensive post-operative care. | Longitudinal study | Fistula Treatment Network | 6,223 surgeries done; training, and centre established; outreach programs and strategic framework developed to End OF. | Integrated approach is effective and scalable for expanding comprehensive fistula care. |

| Vowles et al., 2023 | Sierra Leone | To explore fistula advocates’ perceptions and their role in recovery and reintegration | Qualitative study | Community education | Advocates motivated by psychosocial support and the use of personal stories to reshape identity, shift perceptions, and reduce stigma. | Advocates experienced psychological and socioeconomic gains; contributed meaningfully to reintegration. |

| Tuncalp et al., 2014 | Nigeria | To quantify fistula backlog through community screenings | Cross-sectional study | Community-based screening | Backlog of 38 women identified for surgery in five days | Standardized screening effective in identifying and referring women in need of surgery. |

| Drew et al., 2016 | Malawi | To assess long-term outcomes of women post-fistula repair | Qualitative study | Fistula Advocates | Women showed strong knowledge on fistula causes, prevention, and improved quality of life. | Repaired women educate communities, support others, and promote care-seeking behaviour |

Obstetric Fistula Community-Based Support Initiatives

COMMUNITY AWARENESS AND EDUCATION

Community-based programs have been central to efforts to raise awareness about OF, reducing stigma, and promoting reintegration. To enhance community understanding and practices related to fistula prevention, treatment, and reintegration, Fistula Care Plus and Fistula Eradication Network partnered with established community-based organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), traditional and religious leaders, and local government structures to cultivate champions for social change. The partnership addressed local barriers and identified facilitators to health information and access to healthcare services. It enhanced their capacity to provide comprehensive maternal health, and improved treatment, recovery, and reintegration outcomes for women with OF. However, recent evidence highlights persistently low awareness of OF among women of reproductive age in Sub-Saharan Africa. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed a low level of awareness and emphasized the need for country specific public health initiatives to raise awareness, reduce delays in treatment and improve recovery outcomes. Some countries have implemented a range of community-based programs aimed at educating populations and improving awareness on the prevention, treatment, and recovery of patients with OF. The Tostan program in West Africa uses a holistic, community-based approach to improve maternal health literacy, address harmful practices, and raise awareness about OF by engaging entire communities and promoting gender equity. The program has increased OF awareness, improved health-seeking behaviours, and reduced stigma and social exclusion of affected women using social and holistic education activities. Additionally, a population-based cross-sectional study conducted in Nigeria, which assessed the prevalence and management of OF, also reported the importance of effective community-level interventions in identifying preventive measures, timely management of labour complications, and increased awareness of fistula prevention and treatment services as key strategies. In Kenya, an initiative aimed at increasing awareness and reducing stigma trained community health volunteers to address the challenges faced by women living with OF, emphasizing the importance of building trust and providing appropriate counselling. This approach led to an increase in the number of fistula repairs, underscoring the role of education and community engagement in improving access to fistula treatment. Meanwhile, involving women impacted by OF as advocates has been suggested as an effective approach to increasing awareness about the condition. In Sierra Leone, women affected by OF were trained to become volunteer fistula advocates. It was shown that women affected by OF can influence existing relationships by initiating supportive, and empowering social interactions between NGO staff and community members. Using women with fistula as advocates will minimize stigmatization and enable access to treatment. These programs succeed through strategic partnerships with local stakeholders, targeted education, and innovative interventions that overcome logistical and sociocultural barriers, ultimately leading to improved health outcomes, and increased surgical uptake. The religious assemblies can also be used to drive community awareness, counselling, and education on OF prevention. Religious leaders in Africa settings are well respected by the community and can serve as advocates, thus assisting healthcare providers to connect with fistula victims. In addition to awareness and knowledge, attitudes also play a vital role. This is buttressed by the report of a community-based study in Ethiopia that revealed unfavourable community attitudes towards OF. Appropriate or positive attitudes involve a comprehensive tailored program engaging all relevant stakeholders. The development of educational initiatives specifically designed to raise awareness about OF among different age groups, genders, and educational backgrounds in the community was recommended.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND REINTEGRATION STRATEGIES

Community engagement is essential in preventing OF and supporting affected women throughout treatment and reintegration. Community providers, religious leaders, and other respected figures within the community play an important role in shaping the experiences of women, especially through their influence in either supporting or challenging cultural practices such as child marriage, one of the main risk factors for OF and through them have access to their societies. The involvement of community leaders acts as a gateway for information dissemination, while the community members are active participants in raising awareness, promoting early care-seeking, and supporting the recovery and reintegration of women affected by fistula. Wegner et al. through data across 15 African and Asian countries, showed that community engagement is potentially the key to eliminating OF. Their findings indicated that community knowledge of OF including causes, prevention, and treatment has improved in some of the most underserved regions. This demonstrates that when communities are educated and involved, they play pivotal role in the prevention and eradication of OF. In fistula care and prevention, surgery relieves the physical pain. However, psychological scars remain because women find it difficult to reintegrate into the communities that have ostracized them before having surgery. Fistula survivors need continuous care until they are restored and reintegrated into the community, even after treatment. All fistula survivors require clinical follow-up, economic and psychosocial support, rehabilitation, and reintegration. Reintegration programs often incorporate vocational training, literacy education, and psychosocial counselling to support women’s return to social and economic life. For example, culturally sensitive reintegration models in Ethiopia, Guinea, and Nigeria have demonstrated positive effects on post-surgical recovery and social acceptance. Reintegration and improved quality of life following fistula repair are influenced by the achievement of continence, alongside factors such as social support, reduced stigma, lower depressive symptoms, and the presence of living children. These community-based strategies help bridge the gap between medical treatment and sustained well-being, making them essential for long-term success in fistula elimination. A study on the overall quality of life before and after fistula repair in Malawi showed that challenges at individual and interpersonal levels differed across the pre- and post-repair periods. In a similar study, Delamou et al. documented the medical pathway and reintegration process of women treated for OF in Guinea through the social immersion program, highlighting its positive effects on post-repair quality of life, particularly among women who experienced successful surgical outcomes. However, the effect may be worse among women with persistent incontinence following repair. This shows the need for client-centred, needs-based rehabilitation and reintegration strategies tailored to individual circumstances. Rehabilitation and reintegration efforts should encompass clinical and community-based components, integrating medical reintegration pathways into broader fistula care strategies either directly or through referral systems. Women with residual urinary incontinence or inoperable OF will require both clinical and community-based rehabilitation and reintegration strategies. Therefore, it is important to establish linkages between women returning to their communities and community-based organizations or social support structures that can provide ongoing health and social support as needed.

COMMUNITY SCREENING

Community screening services are important in addressing the backlog of women living with OF by identifying undiagnosed cases and reducing the number of untreated patients within the community. The goal is to provide easy access to treatment, rehabilitation, and reintegration after identification. Community screening should be integrated into maternal and reproductive health outreach programs, particularly in remote areas with limited access to hospitals and clinics, to facilitate early detection, referral of OF cases and build community trust in health systems, which is essential for long-term community engagement. The screening processes involve raising awareness of OF within the community, screening with standardized tools, and helping those affected seek help while eliminating barriers to accessible healthcare services. A cross-sectional study conducted in Nigeria demonstrated the effectiveness of community screening in identifying and treating fistula cases that constitute backlogs. The study further emphasized the cost-effectiveness on both financial and human resources when such approaches are deplored, with its positive approach to identifying the large population of women requiring surgery and connecting them with surgical facilities. The community screening approach for OF has also opened a new frontier in helping identify other reproductive health diseases such as uterine prolapse, and other forms of incontinence amendable to treatment. Partners such as Engender Health, Fistula Foundation, and Fistula Care network have different questionnaires to aid community screening and improve efficiency. Expanding access to screening and referral services through innovative, evidence-based approaches that actively engage the community will address fistula clients’ needs and clear the existing backlog of cases that require treatment. Furthermore, training local healthcare providers and volunteers ensures sustainability and empowers the community to be a part of the success stories. This holistic approach improves community health outcomes and creates a ripple effect that extends beyond OF.

ECONOMIC SUPPORT FOR FISTULA SURVIVORS

Economic consequences of OF are complicated, pervasive, and are entwined with the physical and psychosocial consequences of the condition. Understanding these consequences can help tailor existing fistula programs to better address the impacts of the condition. For instance, the Freedom from Fistula Foundation is dedicated to eradicating OF but recognizes that true recovery goes beyond surgical repair. This foundation emphasizes that economic empowerment is essential for restoring dignity and securing a brighter future for affected women. Therefore, through its Patient Rehabilitation, Education and Empowerment Program, it provides comprehensive post-surgical support to facilitate reintegration into society. This program equips women with life skills tailored to their individual educational backgrounds, including literacy and numeracy, vocational training in sewing, weaving, and beading, as well as practical lessons in cooking meals on a budget. Additionally, patients receive training in micro-finance and enterprise development, covering areas such as opening bank accounts, budgeting, and simple business management. Income-generating activities enable patients with OF post-repair to become financially independent. Ultimately, these initiatives not only transform the lives of the women but also contribute to the prosperity of the communities that once marginalized them. Furthermore, in Nigeria, Mohammad reported the success of the FORWARD approach initiative, which combined surgical repair, skills development, and reintegration support. Women reported improved awareness of their rights, better mental health, and active participation in community development programs. Comprehensive economic empowerment is a critical component of OF recovery, as it not only restores the dignity and self-sufficiency of affected women but also fosters long-term community development and social reintegration.

PSYCHOSOCIAL SUPPORT

Psychosocial support in the context of OF involves addressing the emotional, social, psychological, and sometimes spiritual needs of women suffering from or at risk of OF. Women affected by OF often undergo severe psychosocial challenges. Many are subjected to social exclusion, rejection by family, friends and community members, and face persistent stigma and discrimination. These experiences frequently contribute to emotional distress, including depression, isolation, diminished self-esteem, and a loss of personal identity. Integrating psychosocial support into fistula prevention and care improves treatment uptake, promotes successful reintegration, and helps shift community attitudes toward survivors. For example, a mixed-methods study in Ethiopia highlighted the ongoing psychological, health, and social issues experienced by women with both treated and untreated OF. Although surgical repair improved aspects of family and social life, many women continued to face unresolved psychosocial problems. The study emphasized the need for comprehensive post-surgical care, including community reintegration support and consistent follow-up services. Community-based initiatives have increasingly included psychosocial components to address these broader challenges and support both prevention and rehabilitation efforts. However, despite their successes, significant barriers remain. These include persistent stigma, marital breakdown, discrimination, low self-esteem, social isolation, and even suicidal ideation further compounded by cultural taboos and limited funding for psychosocial programs. Access to effective psychosocial support services remains inadequate. There is a critical need to expand comprehensive rehabilitation and reintegration programs in regions within the fistula belt. Addressing the psychological and social dimensions of OF is essential to developing holistic and sustainable interventions. Strengthening these initiatives will require stable funding, culturally sensitive training of local personnel, and more research into the long-term psychosocial outcomes for fistula survivors.

CAPACITY BUILDING

Building capacity at community levels is essential for increasing awareness, improving access to care, and supporting the recovery of women living with OF. Training programmes for community volunteers, community health workers, and local leaders bridge care gaps, reduce stigma, and helps overcome barriers to treatment and reintegration. In Uganda, FIGO and partners enhanced the training of Village Health Teams with tools and practical content for promoting maternal health and tracking service utilization. These initiatives highlight how community-level training complements broader health system reforms. Similarly, the Action on Fistula (AOF) initiative in Kenya demonstrated how extensive community outreach and training of surgeons and community health workers can effectively expand fistula care access and services. The program reached women across all counties, with over 85% of patients receiving treatment, a significant increase compared to previous coverage levels. Long-term follow-up also indicated positive outcomes in continence, psychological wellbeing, and socioeconomic status. Following the success of the AOF model in Kenya, its expansion to Zambia also led to a marked increase in the number of fistula surgeries performed, significantly improving awareness and treatment access. Training community health workers and volunteers are vital to eliminating OF because they provide culturally sensitive education, dispel myths, reduce stigma, and support survivors through reintegration. However, challenges remain, these include lack of standardized training and weak integration of these workers into the national health strategies. To sustainably eliminate OF, long-term investments are required in structured training for community workers, continuous capacity building, and stronger linkages with formal health systems. Similarly, the FIGO Fistula Surgery Training Initiative and Fistula Care Plus strengthened the capacity of local surgeons in fistula-affected countries by providing training tailored to individual skill levels and extended it to multidisciplinary teams to ensure holistic care. Nine and seven years after their respective launches, the initiatives had completed over 10,000 and 15,000 surgeries, respectively, achieving an impressive success rate of 84% – 87%. Training of all healthcare providers in the prevention and optimal care of OF is a cornerstone intervention for its elimination, with investments in the provider training leading to measurable progress in improving access to fistula care. While these efforts demonstrate substantial progress in capacity building and backlog reduction, the global goal of eradicating obstetric fistula by 2030 remains a considerable challenge. Sustained progress in OF care will require continuous community capacity building and strengthening of the health system.

Challenges and Barriers to Effective Community-based Support Interventions

Despite progress in OF care, numerous barriers continue to hinder the effectiveness of community-based interventions. These challenges exist across individuals, communities, and systemic levels. Identified barriers include psychosocial and cultural factors, low awareness, social stigma, financial limitations, transportation difficulties, inadequate facilities, and weak political leadership. Mahmoodi et al. identified additional structural challenges to implementing community-based health programs, such as government-related inefficiencies, poorly designed health initiatives, limited competencies among healthcare providers, inadequate interdepartmental coordination, unclear program objectives, lack of transparency in role distribution, and insufficient understanding of program benefits. These logistical, structural, and systemic challenges are particularly severe in rural areas, where they significantly restrict community outreach, leaving many women undiagnosed and untreated. A focused ethnographic study by Sullivan et al. in northern Ghana explored how women living with or previously affected by OF, alongside their families and care providers, perceived the support available to them. The study reported support from spouses, family members, and other women regarding food, transportation, and where to live is considered tangible aid that positively impacted their recovery process. However, the informational support provided by NGOs was often not easily comprehensible to the affected women and their families. Other significant barriers to care were the high cost and difficulty of travel to treatment centres, the unpredictable timing of surgery, and the inability to readily access food and basic needs at the treatment centers. This reflects the need to develop targeted community-based interventions that improve awareness, education, decentralise services, and strengthen the overall support system for women living with fistula. Sociocultural stigma and gender norms also prevent women from seeking support, further isolating them from available resources and care. Bellows et al. illustrated how community-based models can assist in recognizing women who face disempowerment and stigma helps tackle the initial barrier of limited awareness and knowledge, while effective transportation and healthcare financing systems that facilitate referrals to surgical centres are crucial for overcoming the second barrier that hinders women from accessing medical care. Importantly, active community involvement in the implementation of health programs not only improves outcomes but also fosters positive social, organizational, and individual transformations.

Future Directions and Recommendations

Efforts to eliminate obstetric fistula in sub-Saharan Africa must extend beyond clinical repair to address the condition’s social, economic, and psychological determinants. Utilizing established networks and collaborations (with government, NGOs, and stakeholders), and providing comprehensive support will enable community-based programs to become a cornerstone of fistula elimination. For example, integrating vocational training, educational opportunities, or counselling services into community initiatives can address underlying risk factors and empower affected women. Obstetric fistula disproportionately affects women and is strongly linked to early marriage and adolescent pregnancy, and obstructed labour. Therefore, prevention efforts should prioritize reproductive health education for young people. Implementing school and community-based programs that target adolescents and their families can raise awareness of reproductive health, the risks of early childbirth, and the importance of family planning. These education initiatives aim to delay early marriage and pregnancy, directly addressing the primary risk factors for fistula. Continued engagement of men, traditional leaders, and religious figures is also essential for sustaining community sensitization and developing gender-transformative programs. Involving these stakeholders can promote shared decision-making and challenge harmful gender norms that contribute to early marriage and pregnancy. Strengthening data collection and monitoring at the community level is critical to track progress. Improving systems to record fistula cases, prevention activities, and social outcomes will support community-based participatory research and integrate fistula indicators into national health information systems. Robust data systems will enable stakeholders to identify gaps, allocate resources effectively, and evaluate the impact of prevention and treatment programs. In addition, periodic community screening initiatives utilising mobile medical units and trained community health volunteers for door-to-door outreach should be institutionalised to enhance early case identification, reduce the backlog of untreated obstetric fistula cases, and ensure sustainable access to care in underserved areas. Combining community mobilization, education, healthcare delivery, and advocacy ensures that different sectors work together to address the complex needs of women and girls affected by fistula. For instance, legal reforms that protect women’s reproductive rights can complement health and education initiatives, creating an integrated framework for fistula prevention and care. Additionally, enhancing sustainable reintegration programs, policy advocacy, and sustainable funding are components of a comprehensive approach. A coordinated multisectoral approach is imperative for sustained progress. Achieving the global goal of eliminating obstetric fistula by 2030 will require coordinated efforts that integrate quality healthcare delivery with empowered community participation. Well-developed community initiatives, supported by sustained investment and strong partnerships, are necessary to ensure that progress is both widespread and sustainable.

Conclusion

Community-based initiatives are critical to addressing OF holistically and sustainably by positioning local actors as key contributors to the elimination of obstetric fistula by 2030. Integrating this approach through a multi-sectoral framework ensures that prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation efforts are comprehensive and culturally responsive. To effectively eradicate OF, efforts must be coordinated, inclusive, and grounded in both clinical excellence and community empowerment. Also, countries and regions with high burden of this morbidity should endeavour to follow up on their strategic plans within the stipulated timeframe while those without such plans should emulate the countries with plans ensuring all hands are on deck to eradicate OF at all levels; national, regional, and local. Eliminating OF globally demands potent political leadership, strategic and urgent intervention that is time-bound, increased resources, and strengthened collaboration between governments, partners, civil society, health care providers, women, and the communities through clinical and community-based interventions.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

2. Wall, L.L. Overcoming phase 1 delays: the critical component of obstetric fistula prevention programs in resource-poor countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-68

3. FIGO: Destigmatising obstetric fistula through education and community engagement – Dr Wanjala’s initiative to train community health volunteers | Figo. Published April 6, 2023. https://www.figo.org/news/destigmatising-obstetric-fistula-through-education-and-community-engagement-dr-wanjalas.

4. Tayler-Smith K, Zachariah R, Manzi M, et al. Obstetric Fistula in Burundi: a comprehensive approach to managing women with this neglected disease. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2013;13(1):164. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-13-164

5. Baker Z, Bellows B, Bach R, Warren C. Barriers to obstetric fistula treatment in low-income countries: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22(8):938-959. doi:10.1111/tmi.12893

6. Ruder B, Emasu A. The Promise and Neglect of Follow-up care in Obstetric Fistula treatment in Uganda. In: Global Maternal and Child Health. 2022:37-55. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-84514-8_3

7. Anindhita M, Haniifah M, Putri AMN, et al. Community-based psychosocial support interventions to reduce stigma and improve mental health of people with infectious diseases: a scoping review. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2024;13(1). doi:10.1186/s40249-024-01257-6

8. Bellows B, Bach R, Baker Z, Warren C. Barriers to Obstetric Fistula Treatment in Low-income Countries: A Systematic Review. Nairobi: Population Council. 2015. https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1940&context=departments_sbsr-rh

9. Fiander A, Ndahani C, Mmuya K, Vanneste T. Results from 2011 for the transportMYpatient program for overcoming transport costs among women seeking treatment for obstetric fistula in Tanzania. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2012;120(3), 292–295. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.09.026

10. Delamou A, Douno M, Bouédouno P, et al. Social Immersion for Women After Repair for Obstetric Fistula: An Experience in Guinea. Front Glob Womens Health. 2021;2:713350. doi:10.3389/fgwh.2021.713350

11. Atuhaire S, Ojengbede OA, Mugisha JF, Odukogbe AA et al., 2018. Social Reintegration and Rehabilitation of Obstetric Fistula Patients Before and After Repair in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. NJOG. 2018;24(1): 5-14.

12. World Health Organization. Maternal Mortality. 2023. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact

13. Bowen C, Draper L, Moore H. 4.5 Community-Based Healthcare Initiatives – Fundamentals of Nursing | OpenStax. Published September 4, 2024.https://openstax.org/books/fundamentals-nursing/pages/4-5-community-based-healthcare-initiatives.

14. Masebo ST MP. Obstetric Fistula Strategic Plan 2022 – 2026.; 2022. https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2023-05/Obstetric%20Fistula%20Strategic%20Plan%202022%20%202026%20Final%281%29.pdf

15. Lavender T, Wakasiaka S, Khisa W. A Multidisciplinary approach to Obstetric fistula in Africa: public health, sociological, and medical perspectives. In: Global Maternal and Child Health. 2022:77-89. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-06314-5_6

16. United Nations. International Day to End Obstetric Fistula | United Nations. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/observances/end-fistula-day.

17. Slinger G, Trautvetter L. Addressing the fistula treatment gap and rising to the 2030 challenge. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 2020;148(S1), 9–15. doi:10.1002/ijgo.13033

18. Johnson EE, O’Connor N, Hilton P, Pearson F, Goh J, Vale L. Interventions for treating obstetric fistula: An evidence gap map. PLOS Global Public Health. 2023;3(1):e0001481. doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0001481

19. Nduka IR, Ali N, Kabasinguzi I, Abdy D. The psycho-social impact of obstetric fistula and available support for women residing in Nigeria: a systematic review. BMC Women S Health. 2023;23(1):87. doi:10.1186/s12905-023-02220-7

20. Debele TZ, Macdonald D, Aldersey HM, Mengistu Z, Mekonnen DG, Batorowicz B. “I became a person again”: Social inclusion and participation experiences of Ethiopian women post-obstetric fistula surgical repair. PLoS ONE. 2024;19(7):e0307021. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0307021

21. Sanni OF, Dada MO, Ariyo AO, Salami AO, Afelumo OL, Ayosanmi OS, Abiodun OP, Sanni EA. The prevalence and management of obstetric fistula among women of reproductive age in a low-resource setting. Health Low-Resour Settings.2023;11(1). doi: 10.4081/hls.2023.11566

22. Hareru HE, Wtsadik DS, Ashenafi E, et al. Variability and awareness of obstetric fistula among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan African countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2023;9(8):e18126. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18126

23. World Health Organization: WHO. Obstetric fistula. Published February 19, 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/10-facts-on-obstetric-fistula

24. Whitcomb K. Obstetric Fistulas in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ballard Brief. Published January 2, 2024. https://ballardbrief.byu.edu/issue-briefs/obstetric-fistulas-in-sub-saharan-africa

25. Obstetric Fistula Strategic Plan. Obstetric Fistula Strategic Plan 2019-2023.; 2019. https://nigeria.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/FMOH-NSF-2019-2023%20Fistula.pdf.

26. Pollaczek L, El Ayadi AM, Mohamed HC. Building a country-wide Fistula Treatment Network in Kenya: results from the first six years (2014-2020). BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):280. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-07351-x

27. Fistula Manual Steering Committee, Mola G, Vangeenderhuysen C, et al. Guiding principles for clinical management and programme development: Obstetric Fistula. (Lewis G, De Bernis L, eds.).; 2005. https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-06/mps%20Fistula2.pdf

28. Adi A. ABUJA: ECOWAS supports 8 countries in Fistula care. Published December 2023. https://www.gbcghanaonline.com/general/abuja-ecowas-supports-8-countries-in-fistula-care/2023/

29. Amref Health Africa, UK. Expanding support for fistula survivors. Published November 2022.

https://amrefuk.org/news/2022/11/expanding-support-for-fistula-survivors-1

30. Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection. MoGCSP Supports Launch of GOFPMSP. https://www.mogcsp.gov.gh/mogcsp-supports-launch-of-gofpmsp/

31. Ghana web. Ghana launches 2024 Obstetric Fistula Programme. Published September 8, 2024. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Ghana-launches-2024-Obstetric-Fistula-Programme-1949642

32. Government, UNFPA launch 2023-2030 National Fistula Strategy. Published June 25, 2023. https://www.nyasatimes.com/government-unfpa-launch-2023-2030-national-fistula-strategy/.

33. Mohammad RH. A community program for women’s health and development: Implications for the long-term care of women with fistulas. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2007; 99(Suppl 1):S137–S142. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.035

34. Mohamed HC, Pollaczek L. It takes a village: The vital role of community organizations in enhancing fistula patient identification, referral, and reintegration in Kenya. Nepal J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;13(2). https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/NJOG/article/view/21924

35. Vowles Z, Bash-Taqi R, Kamara A, et al. The effect of becoming a fistula advocate on the recovery of women with obstetric fistula in Sierra Leone: A qualitative study. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3(4): e0000765. doi.org/10.1371/journal. pgph.00007 65

36. Tunçalp Ö, Isah A, Landry E, Stanton CK. Community-based screening for obstetric fistula in Nigeria: a novel approach. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):44. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-14-44

37. Drew LB, Wilkinson JP, Nundwe W, et al. Long-term outcomes for women after obstetric fistula repair in Lilongwe, Malawi: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2016;16(1):2. doi:10.1186/s12884-015-0755-1

38. United States Agency for International Development, EngenderHealth. Fistula Care Plus: Key Achievements and the Way Forward to End Fistula. 2021. https://www.engenderhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/imported-files/Fistula-Care-Plus-Key-Achievements-and-the-Way-Forward-to-End-Fistula.pdf.

39. Miller S, Lester F, Webster M, Cowan B. Obstetric fistula: a preventable tragedy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50(4):286-294. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.03.009

40. Oluwasola TAO, Bello OO. Clinical and Psychosocial Outcomes of Obstetrics Fistulae in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of Literature. J Basic Clin Reprod Sci. 2020;9(1):8-16. doi: 10.4103/2278- 960X.1945139

41. Chanie WF, Berhe A, Tilahun AD, et al. Community perceptions and determinants of obstetric fistula across gender lines. Scientific Reports. 2025;15(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-025-87192-4

42. Lufumpa, E, Doos L, Lindenmeyer, A. Barriers and facilitators to preventive interventions for the development of obstetric fistulas among women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):155. doi:10.1186/s12884-018-1787-0

43. Wegner MN, Ruminjo J, Sinclair E, Pesso L, Mehta M. Improving community knowledge of obstetric fistula prevention and treatment. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2007;99(1): S108-S111. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.030

44. Freedom From Fistula USA. Economic empowerment – Freedom from fistula USA. Published August 18, 2024. https://www.freedomfromfistula.org/economic-empowerment/

45. Muleta M, Hamlin EC, Fantahun M, Kennedy RC, Tafesse B. Health and social problems encountered by treated and untreated obstetric fistula patients in rural Ethiopia. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(1):44-50. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32712-8

46. Swain D, Parida SP, Jena SK, Das M, Das H. Prevalence and risk factors of obstetric fistula: implementation of a need-based preventive action plan in a South-eastern rural community of India. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):40. doi:10.1186/s12905-020-00906-w

47. Mahmoodi H, Bolbanabad AM, Shaghaghi A, Zokaie M, Gheshlagh RG, Afkhamzadeh A. Barriers to implementing health programs based on community participation: the Q method derived perspectives of healthcare professional. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-023-16961-5

48. Sullivan G, O’Brien B, Mwini-Nyaledzigbor P. Sources of support for women experiencing obstetric fistula in northern Ghana: A focused ethnography. Midwifery. 2016;40:162-168. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2016.07.005