Dual Role of GPx4 in Ferroptosis and Disease Therapy

Unraveling the Dual Nature of GPx4: From Ferroptosis Regulation to Therapeutic Innovation in Human Pathologies

Chunxia Wu 1, Yi Zhao 1, Jianpeng Wang 2, Leina Ma 1

- Department of Oncology, Cancer Institute of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao University, Qingdao Cancer Institute, Qingdao, 266000, Shandong, China.

- Department of Neurosurgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, Shandong Province

* Correspondence: [email protected], [email protected]

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED 31 August 2025

CITATION Wu, C., Zhao, Y., et al., 2025. Unraveling the Dual Nature of GPx4: From Ferroptosis Regulation to Therapeutic Innovation in Human Pathologies. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6801

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6801

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

GPx4 (Glutathione peroxidase 4) is a Sec (selenocysteine)-dependent monomeric antioxidant enzyme capable of maintaining cellular redox homeostasis by catalyzing the reduction of lipid peroxides by GSH (glutathione). As a core regulatory node of the ferroptosis pathway, GPx4 not only directly affects apoptosis, but also deeply participates in tumorigenesis, cellular senescence, and other key biological processes by inhibiting the lipid peroxidation cascade; at the same time, GPx4 also exhibits a key targeting value in neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disorders, and cardiovascular pathologies. The aim of this paper is to analyze the protein structure and biological function of GPx4, to systematically explore the core regulatory role of this enzyme in the ferroptosis pathway and its molecular mechanism in various diseases, and ultimately to break through the existing therapeutic bottlenecks based on the current progress of research, and to provide a new idea for the precise intervention strategy targeting GPx4.

Keywords: GPx4; Ferroptosis; Disease

Introduction

The GPx family is a family of selenium-containing antioxidant enzymes, and the common feature of the proteins in the family is the presence of cysteine as a key functional residue in redox reactions in the center of their catalytic activity. The GPx proteins were first identified in 1982, when Ursini’s team isolated a novel peroxidation inhibitory protein with a molecular weight of 20 kDa for the first time from porcine liver cytosol, and found that the protein in the presence of GSH (glutathione), it significantly inhibited peroxidative damage to phosphatidylcholine liposomes and biological membranes. The human GPx family contains eight isoforms, which differ significantly in tissue distribution, structural features, functional localization, and substrate selectivity, including gastrointestinal-type GPx2, which is localized in the gastrointestinal tract, plasma-type GPx3, and phospholipid peroxidation-type GPx4, etc. GPx4 is a key antioxidant enzyme in the organism and GPx4 once known as PHGPx, is the star molecule in the GPx family and has a special status due to its unique ability to reduce phospholipid peroxides.

1 GPx4 Overview

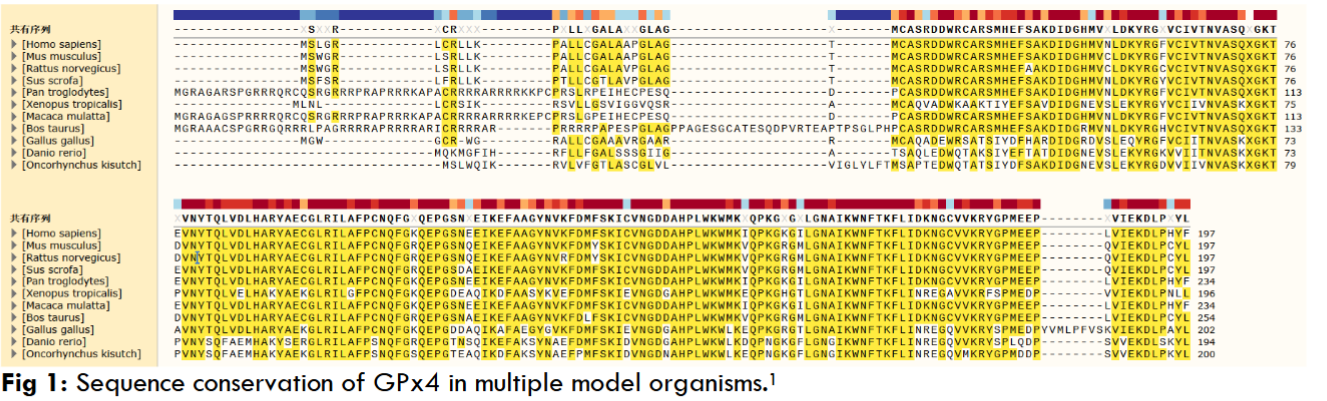

The GPx4 gene is located at the position of sub-band 3 in the main band 13 of the short arm of chromosome 19 in the human genome and the full length of the GPx4 gene is 2865 bases. From this study using X-rays it was resolved that GPx4 is a monomeric protein containing four α-helices and seven β-strands, and the most critical finding was that it lacks a surface loop structural domain, which explains why GPx4 is able to contact complex lipid substrates. Moreover, this study found that the catalytic triad of GPx4 is located on a flat surface surrounded by basic amino acid patches, K48/K135/R152/T139, and this particular conformation supports its broad-spectrum substrate specificity, and several studies have demonstrated that the molecular weight of GPx4 proteins is 19-22 kDa. Moreover, we compared the amino acid sequences of GPx4 protein in various model organisms using sequence analysis software (SNAPGENE, 6.0.2, San Diego, CA, US) and found that it was highly conserved (Figure 1), making it a cross-species universal model for studying ferroptosis mechanisms and accelerating the clinical translation of anticancer and neuroprotective drugs targeting this protein.

GPx4 is a selenocysteine-containing glutathione peroxidase whose core biochemical property is to utilize glutathione to specifically reduce phospholipid hydroperoxides in cell membranes. This unique lipid-repairing ability makes it a key molecular defender in inhibiting lipid peroxidation and preventing ferroptosis, which is essential for cell survival and organismal development.

In general, the GPx4 gene is capable of expressing three isoforms, which are generated by selective promoter or mRNA splicing to generate different isoforms. The three isoforms are cytoplasmic (c-GPx4), mitochondrial (m-GPx4) and nuclear (n-GPx4). The classification of the three subtypes of proteins is closely related to their functions, for example, c-GPx4 plays an important role in the defense against ferroptosis, which can scavenge intracytoplasmic lipid peroxides, maintain intracellular redox homeostasis, and participate in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, and antiferrodeath. m-GPx4 has a mitochondrial signal at its N-terminal end, so that the m-GPx4 protein targeting localizes to the mitochondria, with its main function is to protect the mitochondrial membrane from lipid peroxidation damage and maintain the structural integrity and function of mitochondria, and it also has the unique function of maintaining energy metabolism and preventing mitochondria-derived ferroptosis. n-GPx4 mainly maintains chromatin cohesion and genetic integrity. n-GPx4 protects the lipids and genetic material in the nucleus from oxidative damage, and some studies have found that n-GPx4 also has the special function of sperm nuclear maturation and safeguarding male reproductive function.

According to the structure and catalytic mechanism of GPx4 protein, it can also be classified into selenium-dependent and non-selenium-dependent; and by species and evolution, it can be classified into mammalian and non-mammalian GPx4 homologs.

2 GPx4 and the regulation of ferroptosis

2.1 GPX4’S CENTRAL ROLE IN FERROPTOSIS

As a selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase, the core function of GPx4 is to directly block the lipid peroxidation chain reaction through the selenocysteine-substituted cysteine in its active center by using reduced GSH to specifically reduce phospholipid hydroperoxides, e.g phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxides in the cell membrane system. This function plays a key role in protecting the integrity of the plasma membrane, mitochondrial membrane and nuclear membrane, and is a central antioxidant mechanism for maintaining cellular redox homeostasis. When it comes to the non-classical functions of GPx4, these include the ability to scavenge lipid hydroperoxides to prevent iron-dependent cell death; also reproductive-specific functions, such as the aforementioned nGPx4 catalyzing sperm protein disulfide bond formation in the nucleus of spermatocytes to drive chromatin densification; and involvement in the repair of ischemia/reperfusion injuries through the inhibition of ferroptosis, as well as in the modulation of drug resistance in cancer cells. We summarize the bidirectional role of GPx4 in Table 1.

| Specific role | Mechanism of action | References |

|---|---|---|

| Neurodegenerative diseases: Protect neurons, delay progression | Reduces phospholipid peroxides and inhibits neuronal ferroptosis | [77,78,79] |

| Ischemia-reperfusion injury: Alleviate organ damage | Scavenges lipid ROS in the heart/kidneys and reduces cell death | [36] |

| Atherosclerosis: Delay plaque progression | Inhibits lipid peroxidation in vascular endothelial cells and reduces foam cell formation | [83,84] |

| Male infertility: Ensure sperm motility | Maintains sperm cell membrane integrity and prevents oxidative damage | [28-30] |

| Malignant tumors: Enhance drug resistance, promote metastasis | Scavenges lipid ROS in tumor cells and inhibits ferroptosis | [67,68] |

| Chemotherapy-resistant tumors: Cause chemotherapy failure | Resists ferroptosis inducers (e.g., erastin) through the System Xc⁻-GSH-GPx4 axis | [69,71] |

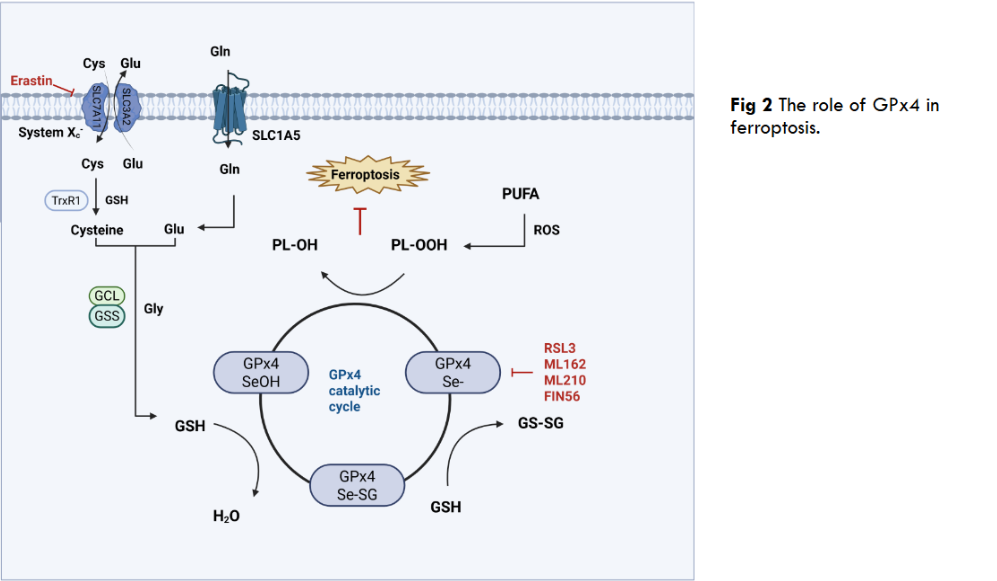

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent, lipid peroxidation-driven form of programmed cell death, the execution of which centers on the uncontrolled accumulation of PL-OOH (phospholipid hydroperoxides), and unlike the accidental necrosis caused by severe external insults, ferroptosis is a form of programmed cell death. GPx4 plays an irreplaceable defense role in ferroptosis, as the only selenoprotein that can directly reduce membrane phospholipid hydroperoxides, GPx4 blocks the lipid peroxidation chain reaction by utilizing GSH to convert toxic PL-OOH into harmless lipid alcohols. This unique repair capacity makes GPx4 the ultimate barrier to inhibit ferroptosis, for example, when GPx4 is targeted by the inhibitor RSL3, genetically deficient, or when upstream GSH synthesis is blocked, PL-OOH accumulates in bursts in cell membranes, especially mitochondrial membranes, triggering membrane integrity disintegration and iron-dependent free radical reactions that directly trigger ferroptosis. Thus, GPx4 activity is a central molecular switch in the ferroptosis pathway, and the System Xc–GSH-GPx4 axis is also a central pathway in the ferroptosis pathway, in which a key member, inhibitory SLC7A11 (solute carrier family 7 member 11), inactivates GPx4 and increases lethal reactive oxygen species by blocking the entry of cysteine into the cell, thereby reducing GSH synthesis and ultimately inducing ferroptosis.

2.2 REGULATORY MECHANISMS OF GPX4

The function of GPx4 is precisely regulated at multiple levels, with post-translational modification being the most rapid response mechanism. CKB (Creatine kinase B) exhibits a non-classical function under oxidative stress rather than a classical metabolic enzyme role, directly phosphorylating the Thr136 site of GPx4 and significantly enhancing its enzymatic activity to resist ferroptosis. It has been shown that AC binds to and promotes ubiquitination of GPx4 protein, leading to degradation of GPx4 via the proteasome pathway, thereby reducing its protein expression level and synergizing with autophagy activation to induce ferroptosis. In addition to the common phosphorylation and ubiquitination, there are also examples of GPx4 being palmitoylated. GPx4 undergoes palmitoylation at the cysteine 66 site, a modification that enhances the protein stability of GPx4 and reduces cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis.

Further, transcriptional regulation remodels GPx4 expression levels through key factors. For example, Nrf2, in this paper, GPx4 is a downstream target of the transcription factor Nrf2, which acts as a transcription factor that influences the ferroptosis process by regulating the expression of GPx4, and the absence of Nrf2 leads to a reduction in the expression of GPx4, which exacerbates ferroptosis and liver injury. In a CCl4-induced acute liver injury model, knockdown of Nrf2 further impaired the protective effect of bicyclol. In p53-mutant colon cancer cells, MDM4 (murine double minute 4) inhibits ubiquitinated degradation of GPx4 by upregulating the expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM21, a regulatory mechanism that allows GPx4 to maintain high protein levels in p53-mutant colon cancer cells, which, in turn, inhibits the occurrence of ferroptosis. At a longer-term epigenetic level, methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs can collectively influence the epigenetic phenomenon of GPx4. PRMT5 (Protein arginine methyltransferase 5)-mediated symmetric dimethylation of GPx4 at arginine position 152 significantly prolongs the half-life of GPx4 by blocking the ubiquitination degradation pathway of the FBW7 E3 ligase, which enhances the resistance of tumor cells to ferroptosis. HDAC9 mediates the deacetylation and ubiquitination of the transcription factor Sp1 through its histone deacetylase activity modification, leading to Sp1 degradation, which inhibits the transcriptional expression of GPx4, a key factor in resistance to ferroptosis, and ultimately drives neuronal ferroptosis in models of cerebral ischemia. Several studies have shown that in many diseases, miRNAs are able to directly target the 3’UTR of GPx4 mRNA to drive its degradation. e.g., in hepatocellular carcinoma, miR-214-3p targets binding to GPx4, which represses GPx4 expression and promotes ferroptosis; miR-211-5p also protects GPx4 indirectly by repressing P2RX7, whose downregulation ultimately lead to the inhibition of GPx4, which in turn induces ferroptosis and aggravates epilepsy. CircRNAs (circular RNAs) such as Circ0060467 can act as ceRNAs (competitive endogenous RNAs) to adsorb these miR-6805 and deregulate their inhibition of GPx4. In addition to non-coding RNAs, RBPs (RNA-binding proteins) are also able to regulate GPx4 expression, e.g., Staphylococcal nuclease SND1 (structural domain-containing protein 1) promotes the degradation of GPx4 by destabilizing HSPA5 (heat shock protein family A member 5) mRNAs and repressing HSPA5 expression to promote ferroptosis of osteoarthritic chondrocytes.

2.3 INTERACTION OF GPX4 WITH OTHER KEY PROTEINS FOR FERROPTOSIS

The precise regulation of ferroptosis relies on a highly synergistic molecular network. As the central antioxidant enzyme of the process, GPx4 does not function in isolation, but together builds a multilayered defense system through close interactions with the System xc–GSH axis, the FSP1-CoQ10 pathway, and ACSL4-mediated lipid metabolism. Ferroptosis inhibitory protein 1 (FSP1), once named AIFM2, was first found to compensate for the enzyme-catalyzed system of GPx4 deficiency, and the discovery of FSP1 revealed a ferroptosis inhibitory pathway that is independent of the GPx4-GSH pathway. FSP1 is localized at the plasma membrane, and utilizes NADPH to reduce ubiquinone (CoQ10) to ubiquinol (CoQ10H₂). CoQ10H₂ acts as a potent lipid-soluble antioxidant that directly neutralizes lipid radicals (L-) and blocks the chain reaction of lipid peroxidation. The functional relationship with GPx4 is reflected as complementary and compensatory, with GPx4 scavenging formed PL-OOH and forming a repair mechanism, whereas FSP1-CoQ10H₂ prevents lipid radical generation and forms a preventive mechanism; transcriptional up-regulation of FSP1 significantly inhibits ferroptosis in GPx4-deficient cells. Long-chain lipoyl coenzyme A synthetase 4 (ACSL4) generates esterified forms of PL-PUFAs (phospholipid-polyunsaturated fatty acids) by catalyzing the binding of PUFAs to coenzyme A. PL-PUFAs are highly susceptible to oxidation by LOXs (lip oxygenase enzymes) to PL-OOH because of their double-bond-rich structure, and become a key substrate for GPx4 action.

3 Disease Associations and Treatment

3.1 GPX4 AND CANCER

GPx4, a key inhibitor of ferroptosis, presents a distinct duality in tumor biology. On the one hand, for normal tissues, GPx4 maintains cell membrane stability and protects normal tissues from oxidative damage by reducing phospholipid peroxides, e.g., the homeostasis of liver and kidney is dependent on its activity, and GPx4 is an important component of the mitochondrial sheath of mammalian spermatozoa; on the other hand, in a variety of malignant tumors, the abnormally high expression of GPx4 scavenges lipid ROS, inhibits ferroptosis and promotes tumor cell survival and proliferation. Clinical studies have shown that GPx4 overexpression is significantly associated with shorter overall survival in pancreatic cancer patients, highlighting its cancer-promoting properties. This paradoxical role stems from the hijacking of oxidative stress defense mechanisms by the tumor microenvironment, which transforms GPx4 from a protector to an accomplice in malignant progression. GPx4-mediated inhibition of ferroptosis is a common mechanism of tumor resistance to conventional therapy, e.g., the accumulation of lipid ROS induced by drugs such as cisplatin can be neutralized by GPx4, weakening its killing effect. Lipid peroxides generated by ionizing radiation depend on GPx4 scavenging to protect tumor stem cell survival, and in head and neck squamous carcinoma GPx4 expression positively correlates with radiotherapy failure. EGFR inhibitor-triggered oxidative stress is mitigated through the GPx4 compensatory pathway and promotes the expansion of drug-resistant clones, as seen in KRAS-mutant colorectal cancer. This broad-spectrum resistance makes GPx4 a key target for overcoming treatment resistance. Therapeutic strategies targeting GPx4 focus on selectively inducing tumor ferroptosis, with small molecules such as RSL3 covalently binding to the selenocysteine active center of GPx4 and directly degrading its function. In an in vivo model, RSL3 significantly inhibited lung metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer. Cutting off GPx4 substrate supply by inhibiting the cystine/glutamate reverse transporter SLC7A11 or depleting glutathione. Erastin combined with a PD-1 antibody remodels the immune microenvironment and enhances anti-tumor response. Despite the promise of cancer treatment by targeting GPx4, its tissue selectivity remains a central challenge. Current innovative strategies are dedicated to balancing efficacy and toxicity, developing tumor microenvironment-responsive prodrugs, and reducing off-target damage to testicular and neural tissues. The dual nature of GPx4 reveals the pivotal role of ferroptosis regulation in cancer therapy. The clinical potential of GPx4 as a “tumor Achilles’ heel” needs to be unlocked through precise intervention strategies in the future to facilitate the translation from pathogenesis to therapeutic innovation.

3.2 GPX4 AND OTHER DISEASES

GPx4 is deeply involved in multifaceted disease pathologies by virtue of its core functions of regulating ferroptosis and maintaining redox homeostasis. From neurodegenerative to metabolic diseases, GPx4 plays a role in all of them. In AD (Alzheimer’s disease) models, Aβ deposition and hyperphosphorylation of Tau proteins cause oxidative stress and activate neuronal ferroptosis, whereas reduced expression or activity of GPx4 exacerbates lipid peroxidation damage and promotes AD progression. Recent studies have found that the natural compound ThA binds to GPx4 and activates the AMPK/Nrf2 pathway, enhancing its antioxidant function and inhibiting ferroptosis in cellular and AD models; one study revealed that MT1 activation inhibits α-syn-induced ferroptosis through the modulation of the Sirt1/Nrf2/Ho1/GPx4 pathway and iron metabolism, exerting a neuroprotective in PD (Parkinson’s disease) role. In ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), GPx4 depletion is present in the spinal cord of both sporadic and familial patients and it is an early and prevalent feature in the spinal cord and brain of ALS mouse models such as SOD1G93A (Superoxide dismutase 1G93A), TDP-43, and C9 or f72, GPx4 depletion and ferroptosis are associated with impaired NRF2 signaling, glutathione synthesis and dysregulation of iron binding proteins. In cardiovascular disease, downregulation of GPx4 expression is present in early and middle stages of myocardial infarction, and its deletion or inhibition leads to accumulation of lipid peroxides in cardiomyocytes and triggers ferroptosis, whereas EGCG (epigallocatechin gallate) inhibits ferroptosis and ameliorates myocardial ischemic injury through upregulation of GPx4, among other pathways; and after intracerebral hemorrhage, clathrin acid improves ferroptosis through cysteine 66 modification of the GPx4 site after intracerebral hemorrhage, alteration enhances its enzymatic activity by alkylation modification, thereby inhibiting neuronal ferroptosis, and the Irg1/cleroconanic acid/GPx4 axis may be a future therapeutic strategy to protect neurons from ferroptosis after intracerebral hemorrhage. In atherosclerosis, GPx4 inhibits lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis through the system xc-/glutathione pathway, and its aberrant expression correlates with ferroptosis in plaque cells e.g., macrophages, vascular endothelial cells, whereas micheliolide inhibits macrophage ferroptosis by upregulating GPx4 and xCT levels through activation of the Nrf2 pathway, thereby reducing atherosclerotic plaque progression. In RA (rheumatoid arthritis), where the expression of GPx4 is elevated and the level of promoter methylation is altered, glycine can promote the methylation of GPx4 promoter by elevating the concentration of SAM (S-adenosylmethionine) promotes GPx4 promoter methylation and reduces its expression, which in turn enhances ferroptosis in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and attenuates synovial hyperproliferation and inflammatory injury, whereas Jinwu Jianbao capsule improves RA symptoms by inhibiting ferroptosis through modulation of the SLC7A11/GSH/GPx4 pathway. In IBD (inflammatory bowel disease), small intestinal epithelial cells of Crohn’s disease patients with impaired GPx4 activity and in IBD, Crohn’s disease patients’ small intestinal epithelial cell GPx4 activity is impaired and LPO (lipid peroxidation) is obvious. ω-6 PUFAs, which are rich in the Western diet, can trigger the cytokine response of epithelial cells, which can be limited by GPx4. Moreover, GZMA can enhance the transcriptional activity of GPx4, inhibit ferroptosis, promote intestinal epithelial cell differentiation, and improve the function of the intestinal barrier by activating the cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling pathway. In SLE (systemic lupus erythematosus), ferroptosis occurs in neutrophils as a result of autoantibody and interferon-alpha induced binding of CREMα (cAMP response element modulator α) to the GPx4 promoter, leading to inhibition of GPx4 expression and elevation of lipid reactive oxygen species, and SLE also induces osteoclast ferroptosis through downregulation of GPx4, leading to vertebral osteoporosis. GPx4 also affects metabolic diseases, such as NAFLD (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease), where cGPx4 protein expression is down-regulated and induces the non-classical transcriptional variant iGPx4, which promotes ferroptosis by interacting with cGPx4 and converting it from an active monomer to an inactive oligomer, and OSA (obstructive sleep apnea), where macrophage-secreted IL6 promotes hepatocyte MARCH3 expression, mediates GPx4 ubiquitination degradation and exacerbates ferroptosis and lipid accumulation. In diabetic complications, PPARα can directly induce the expression of GPx4 by binding to the PPRE element in intron 3 of GPx4 and inhibit the plasma iron carrier TRF, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis and attenuating tissue damage caused by iron overload. These findings reveal a common regulatory mechanism of GPx4 in multi-system diseases and provide a theoretical basis for the development of cross-disease GPx4-targeted therapies.

4 Current status of GPx4 drug development

In recent years, with the continuous deepening of the research on ferroptosis mechanism, targeting GPx4, as the core protein of ferroptosis regulation, has become a highly promising therapeutic strategy. In the field of oncology, many cancer cells rely on the high expression of GPx4 to evade ferroptosis for proliferation, migration and drug resistance, which makes GPx4 an important target for antitumor drug development. However, the development of effective drugs targeting GPx4 faces many challenges. However, as researchers continue to explore and innovate, a variety of novel therapeutic strategies for targeting GPx4 have emerged, bringing new hope for disease treatment.

In terms of covalent inhibitors, GPx4 has a unique structure with a shallow binding pocket, with which conventional small molecule inhibitors bind with limited affinity and selectivity, like the classical RSL3, which inhibits the growth of DRD cells when the compound is present at concentrations as low as 10 ng/mL and initiates the process of killing sensitive cells after 8 hours of treatment. It showed activity in all tested cancer cells harboring oncogenic KRAS with an IC50 of 20 ng/mL. Numerous cells in the NCI-60 cell bank showed specific sensitivity to RSL3 treatment at nmol concentrations, which are sufficient to trigger growth arrest or cell death. In addition to the classical RSL3, there is also ML162, a drug with a similar mechanism of action to RSL3, and C18, as a derivative optimized based on RSL3, not only has a significantly higher inhibitory activity, but also has a better in vivo antitumor effect and lower toxicity, C18 may be a promising covalent inhibitor of GPx4 that induces ferroptosis for the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. Novel covalent inhibitors such as ML210, which uses nitroisoxazole as a prodrug form and covalently binds GPx4 after intracellular conversion to an electrophilic moiety, have selectivity and pharmacokinetic properties superior to that of chloroacetamide inhibitors, and BCP-T.A, a thiazole analog containing an alkyne-based electrophilic moiety, has been found to have inhibitory activity on specific cells up to the low-nanomolar level with high selectivity. PROTAC-degrading agents are a new direction in drug development for targeting GPx4. dGPx4, using ML162 as a warhead and connected to CRBNE3 ligase, has an enhanced anti-tumor effect in vivo after delivery via lipid nanoparticles; DC2, designed based on ML210, degrades GPx4 not only by the proteasomal pathway, but also by autophagy pathway to inhibit tumor growth in vivo. The effect is superior to that of ML210; 8e, as an RSL3-based PROTAC, recruits VHLE3 ligase, which not only effectively induces GPx4 degradation, but also inhibits the growth of drug-resistant tumors. Cell type-specific degradation agents provide a solution to reduce toxicity to normal tissues. N6F11, the first of its kind, activates the tumor cell-specific protein TRIM25, which indirectly induces GPx4 degradation, uniquely inducing ferroptosis only in tumor cells without affecting immune cells and enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Combination therapy strategies have also received much attention. Combining KRASG12C inhibitors, such as sotorasib, as KRAS mutant tumors are highly dependent on GPx4 for survival. Screening of sensitive patients based on lipid peroxidation imaging or GPx4 activity profiles enables individualized dosing. In terms of combining with ferroptosis-related targets, FSP1 inhibitors in combination with GPx4 inhibitors, for example, RSL3 in combination with NPD4928 and icFSP1 can synergistically induce ferroptosis, overcoming the compensatory resistance of the tumor cells; DHODH inhibitors in combination with GPx4 inhibitors can inhibit mitochondrial lipid peroxidation defenses, which is more effective in tumors with high GPx4 expression. In immunotherapeutic combination, GPx4 inhibitor combined with anti-PD-1 antibody enhanced CD8+ T cell infiltration and anti-tumor immunity while inducing tumor ferroptosis, revealing an innovative immunotherapeutic combination strategy for refractory LAR tumors. In radiotherapy combination, Tubastatin A overcomes tumor cell radiotherapy resistance and enhances the efficacy of radiotherapy. In combination with chemotherapy or targeted drugs, RSL3, in combination with TKIs (tyrosine kinase inhibitors), was able to reverse tumor resistance to drugs such as Gefitinib and Osimertinib and synergistically kill tumor cells.

| Drug Name | Description | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSL3 | A covalent inhibitor targeting GPx4 | Covalently binds to the selenocysteine active center of GPx4, directly inhibiting its function and inducing ferroptosis in tumor cells | Effective against cancer cells harboring oncogenic KRAS; induces growth arrest or cell death at nanomolar concentrations | [72,73] |

| ML162 | A covalent inhibitor with a mechanism similar to RSL3 | Inhibits GPx4 function by binding to its active site | Suppresses GPx4 activity and induces ferroptosis | [94] |

| C18 | An optimized derivative based on RSL3 | Acts as a covalent GPx4 inhibitor, binding to its active site to suppress function and induce ferroptosis | Exhibits significantly enhanced inhibitory activity, better in vivo antitumor efficacy, and lower toxicity | [95] |

| ML210 | A novel covalent inhibitor with a nitroisoxazole prodrug moiety | Converts to an electrophilic group intracellularly, then covalently binds to GPx4 to inhibit its function | Superior selectivity and pharmacokinetic properties compared to chloroacetamide inhibitors | [96,97] |

| BCP-T.A | A thiazole analog containing an alkyne-based electrophilic moiety | Interacts with GPx4 via its alkyne electrophilic group to inhibit function | Achieves low-nanomolar inhibitory activity against specific cells with high selectivity | [98,99] |

| dGPx4 | A PROTAC degrader with ML162 as the warhead, linked to CRBN E3 ligase | Degrades GPx4 by recruiting CRBN E3 ligase through PROTAC technology | Enhances in vivo antitumor efficacy when delivered via lipid nanoparticles | [100] |

| DC2 | A PROTAC degrader designed based on ML210 | Degrades GPx4 through both proteasomal and autophagic pathways | Shows better in vivo tumor growth inhibition than ML210 | [96] |

| 8e | An RSL3-based PROTAC that recruits VHL E3 ligase | Induces GPx4 degradation by recruiting VHL E3 ligase via PROTAC technology | Effectively degrades GPx4 and inhibits the growth of drug-resistant tumors | [101] |

| N6F11 | The first cell type-specific degrader | Indirectly induces GPx4 degradation by activating tumor-specific protein TRIM25 | Induces ferroptosis specifically in tumor cells without affecting immune cells; enhances the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors | [68,102] |

5 Conclusions

This review systematically elucidates the structure and function of GPx4, focusing on its central position in the regulation of ferroptosis and its involvement in the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of a variety of diseases. As a specialized glutathione peroxidase containing selenocysteine substituting cysteine, GPx4 plays an irreplaceable role in maintaining cell membrane integrity and protecting cells from oxidative damage by specifically reducing phospholipid hydroperoxides. This unique antioxidant function makes it a key molecular switch linking oxidative stress to cell fate determination. Notably, GPx4 plays a protective role against normal tissues in the physiological state, whereas it exhibits pro-survival properties in the tumor microenvironment, and this seemingly contradictory dual function has brought new ideas for cancer therapy. In recent years, breakthroughs have been made in targeted intervention strategies against GPx4, from early covalent inhibitors such as RSL3, to the emerging PROTAC degradation technology, to the combined application of multiple therapeutic modalities. These innovative studies have not only deepened our understanding of the function of GPx4, but also provided practical solutions to overcome the resistance of tumor therapy. What is even more exciting is that the regulatory network of GPx4 is not only in the field of cancer, but also in neuroprotection in neurodegenerative diseases, myocardial protection in cardiovascular diseases, inflammation regulation in autoimmune diseases, and maintenance of lipid homeostasis in metabolic diseases, etc. These discoveries have demonstrated that GPx4 has a wide range of applications. These findings demonstrate the centrality of GPx4 as a “guardian of oxidative stress” in human health and disease.

Although significant progress has been made in therapeutic strategies targeting GPx4, many challenges remain in clinical translation. Future research should focus on drug design to develop novel inhibitors with higher targeting and lower toxicity; on therapeutic strategies to explore optimal combinations of GPx4 inhibitors with existing therapeutic tools, and ultimately to translate the laboratory results into clinical therapeutic solutions through solid translational medicine research. As these research directions continue to deepen, GPx4-targeted therapies will bring breakthroughs in the treatment of a variety of diseases, which will not only provide new treatment options for cancer patients, but also is expected to open up new avenues in the fields of neuroprotection and cardiovascular disease prevention, and to promote the development of individualized medicine to a higher level. Advances in this field will continue to enrich our understanding of oxidative stress and cell fate determination, and make significant contributions to the cause of human health.

Author contributions

CW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Writing – review & editing. JW: Writing – review & editing. LM: Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos.82372806)

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Flohe L, Toppo S, Orian L. The Glutathione Peroxidase Family: Discoveries and Mechanism. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;187

2. Trenz TS, Delaix CL, Turchetto-Zolet AC et al. Going Forward and Back: the Complex Evolutionary History of the GPx. Biology (Basel). 2021;10

3. Ursini F, Maiorino M, Valente M, Ferri L, Gregolin C. Purification from Pig Liver of a Protein Which Protects Liposomes and Biomembranes from Peroxidative Degradation and Exhibits Glutathione Peroxidase Activity on Phosphatidylcholine Hydroperoxides. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Lipids and Lipid Metabolism. 1982;710:197-211

4. Pei J, Pan X, Wei G, Hua Y. Research Progress of Glutathione Peroxidase Family (GPX) in Redoxidation. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14

5. Brigelius-Flohé R, Kipp AP. Physiological functions of GPx2 and its role in inflammation-triggered carcinogenesis. ENVIRONMENTAL STRESSORS IN BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE. 2012;1259:19-25

6. Nirgude S, Choudhary B. Insights into the role of GPX3, a highly efficient plasma antioxidant, in cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;184

7. Brigelius-Flohe R. Glutathione Peroxidases and Redox-Regulated Transcription Factors. Oxidative Stress and Signal Transduction. 1997:415-440

8. Zhang W, Liu Y, Liao Y, Zhu C, Zou Z. GPX4, ferroptosis, and diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;174:116512

9. Kelner MJ, Montoya MA. Structural Organization of the Human Selenium-Dependent Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase Gene (gpx4): Chromosomal Localization to 19P13.3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:53-55

10. Knopp EA, Arndt TL, Eng KL et al. Murine Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase: Cdna Sequence, Tissue Expression, and Mapping. Mamm Genome. 1999;10:601-605

11. Scheerer P, Borchert A, Krauss N et al. Structural Basis for Catalytic Activity and Enzyme Polymerization of Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase-4 (Gpx4). Biochemistry. 2007;46 31:9041-9

12. Roveri A, Maiorino M, Nisii C, UrsinI F. Purification and Characterization of Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase from Rat Testis Mitochondrial Membranes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Proteins and Proteomics. 1994;1208:211-221

13. Sok SPM, Pipkin K, Van Remmen H, Fan Z, Zhao M. Gpx4 Regulates Invariant NKT Cell Homeostasis and Function by Preventing Lipid Peroxidation and Ferroptosis. J Immunol. 2024;212

14. Li Z, Zhu Z, Liu Y, Liu Y, Zhao H. Function and Regulation of GPX4 in the Development and Progression of Fibrotic Disease. J Cell Physiol. 2022;237:2808-2824

15. Pillai R, Uyehara-Lock JH, Bellinger FP. Selenium and selenoprotein function in brain disorders. IUBMB Life. 2014;66:229-239

16. Miao Y, Chen Y, Xue F et al. Contribution of Ferroptosis and GPX4’s Dual Functions to Osteoarthritis Progression. EBioMedicine. 2022;76:103847-103847

17. Seibt TM, Proneth B, Conrad M. Role of GPX4 in Ferroptosis and Its Pharmacological Implication. Free radical biology & medicine. 2018;133:144-152

18. Forcina GC, Dixon SJ. GPX4 at the Crossroads of Lipid Homeostasis and Ferroptosis. Proteomics. 2019;19.0:e1800311

19. Imai H, Nakagawa Y. Biological Significance of Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase (phgpx, GPx4) in Mammalian Cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34

20. Brigelius-Flohe R. Tissue-Specific Functions of Individual Glutathione Peroxidases. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27

21. Xie Y, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Tang D. GPX4 in Cell Death, Autophagy, and Disease. Autophagy. 2023;19:2621-2638

22. Arai M, Imai H, Sumi D et al. Import into Mitochondria of Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase Requires A Leader Sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227

23. Nomura K, Imai H, Koumura T, Kobayashi T, Nakagawa Y. Mitochondrial Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase Inhibits the Release of Cytochrome C from Mitochondria by Suppressing the Peroxidation of Cardiolipin in Hypoglycaemia-Induced Apoptosis. Biochem J. 2000;351:183-193

24. Arai M, Imai H, Koumura T et al. Mitochondrial phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase plays a major role in preventing oxidative injury to cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(8):4924-33

25. Ursini F, Heim S, Kiess M et al. Dual Function of the Selenoprotein PHGPx During Sperm Maturation. Science. 1999;285:1393-1396

26. Liu Y, Wan Y, Jiang Y, Zhang L, Cheng W. GPX4: The hub of lipid oxidation, ferroptosis, disease and treatment. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Reviews on Cancer. 2023;1878

27. Conrad M, Moreno SG, Sinowatz F et al. The Nuclear Form of Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase is a Protein Thiol Peroxidase Contributing to Sperm Chromatin Stability. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7637-7644

28. Puglisi R, Maccari I, Pipolo S et al. The Nuclear Form of Glutathione Peroxidase 4 is Associated with Sperm Nuclear Matrix and is Required for Proper Paternal Chromatin Decondensation at Fertilization. J Cell Physiol. 2011;227:1420-1427

29. Pfeifer H, Conrad M, Roethlein D et al. Identification of A Specific Sperm Nuclei Selenoenzyme Necessary for Protamine Thiol Cross-Linking During Sperm Maturation. ?The ?FASEB journal. 2001;15:1236-1238

30. 30. Pipolo S, Puglisi R, Mularoni V et al. Involvement of Sperm Acetylated Histones and the Nuclear Isoform of Glutathione Peroxidase 4 in Fertilization. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233

31. Ursini F, Maiorino M. Lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis: The role of GSH and GPx4. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;152:175-185

32. Maiorino M, Thomas JP, Girotti AW, Ursini F. Reactivity of Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase with Membrane and Lipoprotein Lipid Hydroperoxides. Free Radical Research Communications. 1991;12:131-135

33. Thomas JP, Maiorino M, Ursini F, Girotti AW. Protective Action of Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase Against Membrane-Damaging Lipid Peroxidation. in Situ Reduction of Phospholipid and Cholesterol Hydroperoxides. Journal of biological chemistry? The ?Journal of biological chemistry. 1990;265:454-461

34. Imai H, Matsuoka M, Kumagai T, Sakamoto T, Koumura T. Lipid Peroxidation-Dependent Cell Death Regulated by GPx4 and Ferroptosis. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology Apoptotic and Non-apoptotic Cell Death. 2016:143-170

35. Maiorino M, Conrad M, Ursini F. GPx4, Lipid Peroxidation, and Cell Death: Discoveries, Rediscoveries, and Open Issues. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2018;29:61-74

36. Wang X, Chen T, Chen S et al. STING Aggravates Ferroptosis-Dependent Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Targeting GPX4 for Autophagic Degradation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:136

37. Dong J, Ma F, Cai M et al. Heat Shock Protein 90 Interactome-Mediated Proteolysis Targeting Chimera (HIM-PROTAC) Degrading Glutathione Peroxidase 4 to Trigger Ferroptosis. J Med Chem. 2024;67

38. 38. Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, Biology and Role in Disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:266-282

39. Zheng J, Conrad M. The Metabolic Underpinnings of Ferroptosis. Cell Metab. 2020;32(6):920-937

40. 40. Dixon SJ. Ferroptosis: Bug or Feature? Immunol Rev. 2017;277

41. Song J, He Y, Zhou K et al. [Research Progress on the Mechanism of Ferroptosis in Septic Cardiomyopathy]. Zhonghua wei zhong bing ji jiu yi xue. 2022;34:1107-1111

42. Ma T, Du J, Zhang Y et al. GPX4-independent Ferroptosis—a New Strategy in Disease’s Therapy. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8:434

43. Gaschler MM, Andia AA, Liu H et al. FINO2 Initiates Ferroptosis Through GPX4 Inactivation and Iron Oxidation. Nat Chem Biol. 2018;14:507-515

44. Hassannia B, Vandenabeele P, Berghe TV. Targeting Ferroptosis to Iron out Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:830-849

45. 45. Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME et al. Regulation of Ferroptotic Cancer Cell Death by Gpx4. Cell. 2014;156

46. Lewerenz J, Hewett SJ, Huang Y et al. The Cystine/Glutamate Antiporter System X(C)(-) in Health and Disease: from Molecular Mechanisms to Novel Therapeutic Opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18

47. Kim DH, Kim WD, Kim SK, Moon DH, Lee SJ. TGF-β1-mediated Repression of SLC7A11 Drives Vulnerability to GPX4 Inhibition in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Cell death and disease. 2020;11

48. Wu K, Yan M, Liu T et al. Creatine Kinase B Suppresses Ferroptosis by Phosphorylating GPX4 Through a Moonlighting Function. Nat Cell Biol. 2023;25

49. Chen Y, Xu W, Liu Y et al. Anomanolide C Suppresses Tumor Progression and Metastasis by Ubiquitinating GPX4-driven Autophagy-Dependent Ferroptosis in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19

50. Huang B, Wang H, Liu S et al. Palmitoylation-dependent Regulation of GPX4 Suppresses Ferroptosis. Nat Commun. 2025;16:1-19

51. Zhao T, Yu Z, Zhou L et al. Regulating Nrf2-GPx4 Axis by Bicyclol Can Prevent Ferroptosis in Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Acute Liver Injury in Mice. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8

52. Liu J, Wei X, Xie Y et al. MDM4 Inhibits Ferroptosis in P53 Mutant Colon Cancer Via Regulating TRIM21/GPX4 Expression. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15

53. Fan Y, Wang Y, Dan W et al. PRMT5-mediated Arginine Methylation Stabilizes GPX4 to Suppress Ferroptosis in Cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2025;27:641-653

54. Sanguigno L, Guida N, Anzilotti S et al. Stroke by Inducing HDAC9-dependent Deacetylation of HIF-1 and Sp1, Promotes TfR1 Transcription and GPX4 Reduction, Thus Determining Ferroptotic Neuronal Death. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:2695-2710

55. He G, Bao N, Wang S et al. Ketamine Induces Ferroptosis of Liver Cancer Cells by Targeting Lncrna PVT1/miR-214-3p/GPX4. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2021;Volume 15:3965-3978

56. 56. Li X, Quan P, Si Y et al. The microRNA-211-5p/P2RX7/ERK/GPX4 axis regulates epilepsy-associated neuronal ferroptosis and oxidative stress. J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21(1):13

57. Tan Y, Jiang B, Feng W et al. Circ0060467 Sponges Mir-6805 to Promote Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression Through Regulating AIFM2 and GPX4 Expression. Aging-US. 2024;16

58. Min L, Yuanzhen C, Weikun H et al. The RNA-binding Protein SND1 Promotes the Degradation of GPX4 by Destabilizing the HSPA5 Mrna and Suppressing HSPA5 Expression, Promoting Ferroptosis in Osteoarthritis Chondrocytes. Inflamm Res. 2022;71:461-472

59. Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R et al. FSP1 is a Glutathione-Independent Ferroptosis Suppressor. Nature. 2019;575:693-698

60. Lv Y, Liang C, Sun Q et al. Structural Insights into FSP1 Catalysis and Ferroptosis Inhibition. Nat Commun. 2023;14

61. Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z et al. The CoQ Oxidoreductase FSP1 Acts Parallel to GPX4 to Inhibit Ferroptosis. Nature. 2019;575:688-692

62. Yuan H, Li X, Zhang X, Kang R, Tang D. Identification of ACSL4 As a Biomarker and Contributor of Ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478:1338-1343

63. Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F et al. Oxidized Arachidonic and Adrenic Pes Navigate Cells to Ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;13:81-90

64. Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY et al. ACSL4 Dictates Ferroptosis Sensitivity by Shaping Cellular Lipid Composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;13:91-98

65. Stockwell BR, Angeli JPF, Bayir H et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell. 2017;171

66. O’Flaherty C, Scarlata E. OXIDATIVE STRESS AND REPRODUCTIVE FUNCTION: the Protection of Mammalian Spermatozoa Against Oxidative Stress. Reproduction. 2022;164:F67-F78

67. Li H, Sun Y, Yao Y et al. USP8-governed GPX4 Homeostasis Orchestrates Ferroptosis and Cancer Immunotherapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2024;121

68. Li J, Liu J, Zhou Z et al. Tumor-specific GPX4 Degradation Enhances Ferroptosis-Initiated Antitumor Immune Response in Mouse Models of Pancreatic Cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2023;15

69. Chen Z, Shan J, Chen M et al. Targeting GPX4 to Induce Ferroptosis Overcomes Chemoresistance Mediated by the PAX8-AS1/GPX4 Axis in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany). 2025:e01042

70. Jehl A, Conrad O, Burgy M et al. Blocking EREG/GPX4 Sensitizes Head and Neck Cancer to Cetuximab Through Ferroptosis Induction. Cells. 2023;12

71. Ma C, Lv Q, Zhang K et al. NRF2-GPX4/SOD2 Axis Imparts Resistance to EGFR-tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Non-Small-cell Lung Cancer Cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;42:613-623

72. Zheng C, Wang C, Sun D et al. Structure-activity Relationship Study of RSL3-based GPX4 Degraders and Its Potential Noncovalent Optimization. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;255

73. Ma F, Li Y, Cai M et al. ML162 Derivatives Incorporating a Naphthoquinone Unit As Ferroptosis/apoptosis Inducers: Design, Synthesis, Anti-Cancer Activity, and Drug-Resistance Reversal Evaluation. Eur J Med Chem. 2024;270

74. Yuan J, Liu C, Jiang C et al. RSL3 Induces Ferroptosis by Activating the NF-κB Signalling Pathway to Enhance the Chemosensitivity of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells to Paclitaxel. Sci Rep. 2025;15

75. Province BRCA, Aihua H, Hassan KNU. Metformin Induces Ferroptosis Byinhibiting UFMylation of SLC7A11 in Breast Cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40

76. Wang S, Le Zhu, Li T et al. Disruption of MerTK Increases the Efficacy of Checkpoint Inhibitor by Enhancing Ferroptosis and Immune Response in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5

77. Yong Y, Yan L, Wei J et al. A Novel Ferroptosis Inhibitor, Thonningianin A, Improves Alzheimer’s Disease by Activating GPX4. Theranostics. 2024;14

78. 78. Costa I, Barbosa DJ, Benfeito S et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Ferroptosis and Their Involvement in Brain Diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2023;244

79. Lv Q, Tao K, Yao X et al. Melatonin MT1 Receptors Regulate the Sirt1/Nrf2/Ho-1/Gpx4 Pathway to Prevent Α-Synuclein-induced Ferroptosis in Parkinson’s Disease. J Pineal Res. 2024;76:e12948

80. Park T, Park JH, Lee GS et al. Quantitative Proteomic Analyses Reveal That GPX4 Downregulation During Myocardial Infarction Contributes to Ferroptosis in Cardiomyocytes. Cell Death and Disease. 2019;10

81. Yu Q, Zhang N, Gan X et al. EGCG Attenuated Acute Myocardial Infarction by Inhibiting Ferroptosis Via Mir-450B-5p/acsl4 Axis. Phytomedicine. 2023;119

82. Wei C, Xiao Z, Zhang Y et al. Itaconate Protects Ferroptotic Neurons by Alkylating GPx4 Post Stroke. Cell Death Differ. 2024;31

83. Luo X, Wang Y, Zhu X et al. MCL Attenuates Atherosclerosis by Suppressing Macrophage Ferroptosis Via Targeting KEAP1/NRF2 Interaction. Redox Biol. 2023;69:102987-102987

84. Xu X, Xu X, Ma M et al. The Mechanisms of Ferroptosis and Its Role in Atherosclerosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;171:116112-116112

85. Ling H, Li M, Yang C et al. Glycine Increased Ferroptosis Via SAM-mediated GPX4 Promoter Methylation in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61:4521-4534

86. Ling Y, Yang Y, Ren N et al. Jinwu Jiangu Capsule Attenuates Rheumatoid Arthritis Via the SLC7A11/GSH/GPX4 Pathway in M1 Macrophages. Phytomedicine. 2024;135

87. Mayr L, Grabherr F, Rzler JS et al. Dietary Lipids Fuel GPX4-restricted Enteritis Resembling Crohn’s Disease. Nat Commun. 2020;11

88. Li P, Jiang M, Li K et al. Glutathione Peroxidase 4–regulated Neutrophil Ferroptosis Induces Systemic Autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:1107-1117

89. Cai W, Wu S, Ming X et al. IL6 Derived from Macrophages under Intermittent Hypoxia Exacerbates NAFLD by Promoting Ferroptosis Via MARCH3‐Led Ubiquitylation of GPX4. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11

90. Xing G, Meng L, Cao S et al. PPARalpha alleviates iron overload-induced ferroptosis in mouse liver. EMBO Rep. 2022;23(8):e52280

91. Borchert A, Kalms J, Roth SR et al. Crystal Structure and Functional Characterization of Selenocysteine-Containing Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Suggests an Alternative Mechanism of Peroxide Reduction. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2018;1863:1095-1107

92. Moosmayer D, Hilpmann A, Hoffmann J et al. Crystal Structures of the Selenoprotein Glutathione Peroxidase 4 in Its Apo Form and in Complex with the Covalently Bound Inhibitor ML162. Acta Crystallographica Section D Structural Biology. 2021;77:237-248

93. Yang WS, Stockwell BR. Synthetic Lethal Screening Identifies Compounds Activating Iron-Dependent, Nonapoptotic Cell Death in Oncogenic-Ras-Harboring Cancer Cells. CHEMISTRY & BIOLOGY. 2008;15

94. Weiwer M, Bittker JA, Lewis TA et al. Development of Small-Molecule Probes That Selectively Kill Cells Induced to Express Mutant Ras. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22

95. Chen T, Leng J, Tan J et al. Discovery of Novel Potent Covalent Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Inhibitors As Highly Selective Ferroptosis Inducers for the Treatment of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J Med Chem. 2023;66:10036-10059

96. Wang H, Wang C, Li B et al. Discovery of ML210-Based Glutathione Peroxidase 4 (GPX4) Degrader Inducing Ferroptosis of Human Cancer Cells. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;254

97. Kathman SG, Cravatt BF. A Masked Zinger to Block GPX4. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;16:482-483

98. Karaj E, Sindi SH, Kuganesan N et al. Tunable Cysteine-Targeting Electrophilic Heteroaromatic Warheads Induce Ferroptosis. J Med Chem. 2022;65

99. Yamada M, Hirose Y, Lin B et al. Design, Synthesis, and Monoamine Oxidase B Selective Inhibitory Activity of N-Arylated Heliamine Analogues. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2022;13:1582-1590

100. Luo T, Zheng Q, Shao L et al. Intracellular Delivery of Glutathione Peroxidase Degrader Induces Ferroptosis in Vivo. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2022;61

101. Zheng C, Wang C, Sun D et al. Structure-activity Relationship Study of RSL3-based GPX4 Degraders and Its Potential Noncovalent Optimization. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;255

102. Liu J, Li J, Kang R, Tang D. Cell Type-Specific Induction of Ferroptosis to Boost Antitumor Immunity. Oncoimmunology. 2023;12

103. Bian Y, Shan G, Bi G et al. Targeting ALDH1A1 to Enhance the Efficacy of KRAS-targeted Therapy Through Ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2024;77

104. Yoshioka H, Kawamura T, Muroi M et al. Identification of a Small Molecule That Enhances Ferroptosis Via Inhibition of Ferroptosis Suppressor Protein 1 (FSP1). ACS Chem Biol. 2022;17:483-491

105. Nakamura T, Hipp C, O ASDM et al. Phase Separation of FSP1 Promotes Ferroptosis. Nature. 2023;619

106. Yao L, Yang N, Zhou W et al. Exploiting Cancer Vulnerabilities by Blocking of the DHODH and GPX4 Pathways: A Multifunctional Bodipy/PROTAC Nanoplatform for the Efficient Synergistic Ferroptosis Therapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12

107. Yang F, Xiao Y, Ding J et al. Ferroptosis Heterogeneity in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Reveals an Innovative Immunotherapy Combination Strategy. Cell Metab. 2022;35:84-100.e8

108. Liu S, Zhang H, Li J et al. Tubastatin A Potently Inhibits GPX4 Activity to Potentiate Cancer Radiotherapy Through Boosting Ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2023;62:102677-102677