Impact of Project ECHO on Burnout in Mental Health Care

The Influence of Project ECHO Participation on Professional Isolation and Burnout Among Geriatric Mental Health Providers

Meaghan S. Adams1,2, Claire Checkland3, Haddas Grosbein4, Alexander Kiss4, James Chau5, Sid Feldman2,6, Faith Boutcher1,2, David K. Conn2,6

- Centre for Education and Knowledge Exchange in Aging, Baycrest Academy for Research & Education, Toronto, ON ; Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON

- Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health, Markham, ON

- Kunin-Lunenfeld Centre for Applied Research and Evaluation (KL-CARE), Baycrest Academy for Research & Education, Toronto, ON

- North East Specialized Geriatric Centre, Sudbury, ON

- Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON; Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care, Toronto, ON

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 September 2025

CITATION: ADAMS, Meaghan S. et al. The Influence of Project ECHO Participation on Professional Isolation and Burnout Among Geriatric Mental Health Providers. Medical Research Archives,. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6917>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6917

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Professional isolation is a contributor to healthcare professionals’ burnout, a critical threat to the well-being and sustainability of the health workforce. One intervention that may be effective in mitigating professional isolation and decreasing burnout risk is a clinically-focused community of practice that prioritizes mentorship and collaboration, which are important aspects of the Project ECHO™ educational model. The present study therefore evaluated whether participating in a pan-Canadian ECHO program focused on building skills and capacity for geriatric mental health care impacted providers’ self-reported experiences with burnout and professional isolation. Using mixed-methods analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, pre- and post-program analysis did not identify any significant changes in self-reported burnout frequency. However, at the end of the program, 18.9% of participants reported that the program had changed their feelings of burnout and 44.2% reported that it had affected their sense of professional isolation. Participant comments spoke to themes of connection and access to valuable knowledge or expertise. While the program successfully enabled participants to access a professional network and valuable clinical resources, the program could not address all of the factors that influence the complex constructs of professional isolation and burnout. Since the program was designed to build clinical skills and capacity in geriatric mental health care, evaluating professional isolation and burnout among participants was a secondary question. The positive secondary effects of Project ECHO™ programs such as this one are important for engagement of healthcare professionals in ongoing professional development and to strengthen the health workforce into the future.

Keywords

Project ECHO, professional isolation, burnout, geriatric mental health, healthcare professionals

Introduction

The mental health of healthcare professionals has come under greater scrutiny since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which not only introduced unprecedented stressors but also magnified long-standing systemic issues. Healthcare providers faced greater exposure to trauma, uncertainty, and moral distress, while enduring conditions that deepened existing vulnerabilities to professional isolation and burnout. These interrelated challenges have emerged as critical threats to the well-being and sustainability of the healthcare workforce.

Professional isolation can be defined as a sense of disconnection from professional peers, including a lack of mentorship, collaboration, and interaction. Geographic isolation may be a major factor leading to feeling professionally isolated, along with ideology, resources available, and social connections. Professional isolation, sometimes called professional loneliness, may also be linked to physical separation, which can lead to limited coordination and collaboration.

Burnout was originally defined in 1974 to refer to the sense of exhaustion experienced in the face of excessive workplace demands on “energy, strength or resources.” It presents as high levels of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and low personal efficacy, which can lead to problems in workers’ physical health, mental health, and relationships. In healthcare, providers experiencing burnout can become emotionally withdrawn from their work, spending less time with patients and becoming less collaborative and patient-centered, all of which can negatively impact the quality of care provided to patients. Burnout becomes a risk as job demands increase and is especially exacerbated when resources are low, conditions which worsened during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. While it has always been a concern, understanding and mitigating burnout must now be an urgent priority for healthcare leaders.

Professional isolation has the potential to contribute to healthcare professionals developing burnout. Feeling isolated and without appropriate emotional and practical supports leaves healthcare professionals vulnerable to higher stress levels and greater emotional strain, key components of burnout. Isolation also undermines team functioning, which is critically important in collaborative, interprofessional care such as geriatrics, leading to negative outcomes for patients and providers, including contributing to burnout. Professional isolation is a risk factor for developing burnout, and they form a feedback loop that negatively impacts healthcare professionals, patients, families, and organizations.

Targeted programs to provide support and resources to healthcare professionals are essential for helping clinicians mitigate professional isolation and burnout. There are many examples of programs designed to address clinician mental health. Through varying means, including participating in support groups or implementing toolkits among their teams, these programs build resilience and provide mental health support for participating clinicians. However, there may be a role for programs not directly targeting mental health outcomes to have additional secondary impacts on the well-being of the healthcare workforce. Programs focused on clinical capacity-building can provide access to resources and practices, and can expand professional networks, which may contribute to mitigating burnout and professional isolation.

Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) was developed in 2003 in response to barriers patients faced in accessing specialized care for treatable conditions. ECHO is a case-based telementoring program for healthcare providers managing complex or chronic conditions. Project ECHO enables healthcare providers to collaborate with one another, share best practices, and discuss challenges they face in their clinical settings. The model was developed to democratize medical knowledge by connecting specialists with community providers through virtual mentorship and collaborative learning networks and has demonstrated effectiveness in improving provider characteristics and improving patient outcomes in a cost-effective manner. These communities of practice have the potential to mitigate isolation and professional stagnation among providers working in remote, rural, or underserved areas. Our team has organized educational programming using the Project ECHO™ model to build capacity in geriatric mental health care and care of the elderly since 2018. Over several iterations, we have demonstrated that our ECHO: Care of the Elderly program effectively builds capacity to care for older adults and positively impacts healthcare practice with long-term care staff and with interprofessional clinicians in various settings from across Canada. Building on these previous successes, a National ECHO: Geriatric Mental Health (GeMH) program was established in 2023 to empower primary care providers across Canada to implement new best-practice guidelines into clinical practice.

This National ECHO: GeMH program was based on the success of an earlier pilot program. It launched in 2023 with the primary educational goal of disseminating a set of novel clinical practice guidelines among interprofessional teams in geriatrics, and to support healthcare providers as they integrated the best practices and evidence into their practices. The program was delivered by an interprofessional specialist hub team from across Canada, including geriatric psychiatrists, family physicians with focused practice in care of the elderly, allied health professionals, knowledge brokers, and administrators. The program was divided into 4 cycles: Essential Topics in Geriatric Mental Health, Dementia, Advanced Topics in Geriatric Mental Health, and Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. Each cycle had a specific focus and was based on one or more sets of guidelines, all of which are available at www.ccsmh.ca.

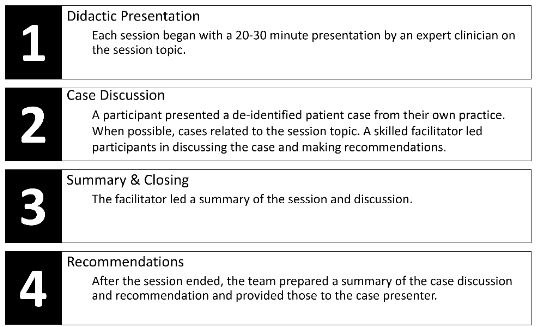

Cycles ran consecutively, with each one consisting of 8-10 sessions. Participants could register for one or more cycles and in all cycles, sessions were 90 minutes in duration and delivered weekly via videoconference. All sessions were led by a skilled facilitator and included both didactic and case-based components.

Although the primary purpose of National ECHO: GeMH was to build clinical capacity for geriatric mental healthcare among interprofessional teams, we hypothesized that participating in a group education program might have secondary benefits to professional isolation and burnout, owing to the delivery structure and program methodology. While participants have reported increased professional satisfaction and engagement as a result of ECHO programming, it is not clear whether participating in a clinically-focused ECHO program would have secondary benefits for providers’ feelings of burnout and professional isolation. Therefore, the objective of this study is to evaluate the effect of participating in National ECHO: Geriatric Mental Health (GeMH) programming on providers’ self-reported experiences with burnout and professional isolation. Specifically, this study tests the hypotheses that: 1) self-reported experiences of professional isolation and burnout would decrease after participating in National ECHO: GeMH; 2) participants in rural and remote practice environments would report greater impacts on professional isolation and burnout than those in urban or suburban areas; and 3) impacts would differ based on participants’ province or territory of residence.

Methods

Participant Recruitment

The National ECHO: GeMH program ran from February 2023 through September 2024. The program was advertised widely across Canada, including through CCSMH and Baycrest ECHO mailing lists, health professional colleges and associations, not-for-profit organizations working with geriatric mental healthcare providers, and professional networks. The program was open to interprofessional providers and healthcare administrators from all provinces and territories across Canada. Interested participants completed a registration form which described the program and requested their consent to participate in program evaluation surveys. Participants were able to join the virtual educational sessions even if they did not consent to participate in evaluation activities. Participants were included in data analysis if they provided consent and attended at least one session. If participants attended multiple cycles, their data were treated as separate records for each cycle they attended.

Data Collection

Because it was hypothesized that participating in ECHO may help to alleviate providers’ sense of professional isolation and burnout, participants were asked before and after participation in the program to report on how often they experienced burnout in the past month. At the end of the program, they were asked whether participating in the ECHO program impacted their sense of professional isolation, and their feelings of burnout (two separate questions), and those who answered “yes”, they were presented with open-ended text fields to provide details. Data were also collected on participant demographics to understand the characteristics of the group participating in ECHO.

Evaluation of the ECHO program consisted of three surveys: a) a pre-program application form completed before the first session began; b) pre- and post-program impact surveys completed before the first session and repeated after the last session; and c) a post-program feedback survey completed after the last session concluded. The surveys included a combination of multiple choice questions, Likert-style ratings, and binary yes/no questions with corresponding open-ended questions for participants to add text to contextualize their responses. Study data were captured using REDCap electronic data collection tools hosted at REDcap.baycrest.org.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative and qualitative techniques. Prior to analysis, data were cleaned to standardize inclusion and data quality, as documentation practices varied slightly between ECHO cycles, and de-identified to remove participants’ identifying information. Quantitative data were reported using descriptive statistics, with Likert scale responses reported as means and standard deviations and binary responses reported as counts and percentages. Linear mixed models were run to account for the correlation among observations among the same individual over time when assessing the outcome of burnout frequency. One model included practice environment and tested the interaction between practice environment and time in relation to burnout. The other model included geographic region and tested the interaction between geographic region and time in relation to burnout. Chi-square analyses were run to compare sense of professional isolation (yes/no) between types of practice environment, as well as between geographic regions. All analyses were run using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). When testing the hypotheses that participants’ experience with burnout and professional isolation would differ based on their practice environment, small sample sizes in some groups required combining groups for analysis. Specifically, participants from remote or rural practice environments were combined, as were participants who endorsed practicing in urban/suburban environments. A third group comprised participants who practiced in urban/suburban environments as well as either rural or remote areas, as we assumed that professional isolation would correlate with geographic isolation and participants with even partial exposure to urban/suburban environments would be less isolated than those with no time in those environments. Additionally, when testing the hypotheses that geographic location impacted professional isolation or burnout, small sample sizes from some provinces meant data were combined into four geographic regions: British Columbia, Prairies (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba), Ontario/Quebec, and Atlantic provinces (Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick). Participants from Yukon and Nunavut were excluded from comparative analyses because there were not enough participants to include in a separate category, and investigators decided that these regions’ geographic uniqueness meant that participant responses to the outcomes of interest may be meaningfully different from other groups to such an extent that they should not be added to one of the other groups.

Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis of responses to open-ended questions to identify common themes. Common themes and subthemes were identified using a deductive coding approach, with subsequent themes derived from topics explored in each of the open-ended survey questions. Primary themes, subthemes, and supportive quotes were presented alongside the quantitative data.

Results

Participant Demographics

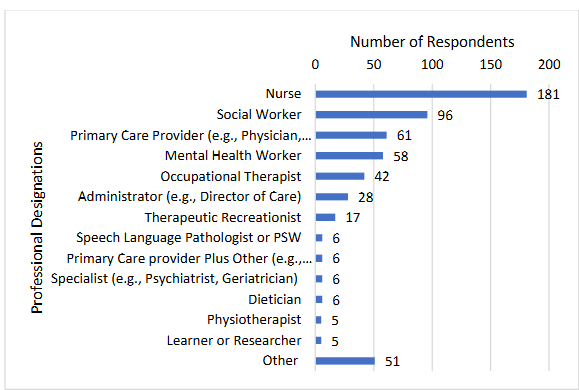

A total of 684 Learning Partners consented to participate in program evaluation for the National ECHO: GeMH education program. Of these, 571 (83.5%) attended at least one session, and demographic data were available for nearly all of them; 513 (90.0%) identified as female, 37 (6.5%) as male, and 20 (3.5%) responded as “other” or preferred to not provide their gender identity. Over half of the participants were nurses, social workers, or primary care providers.

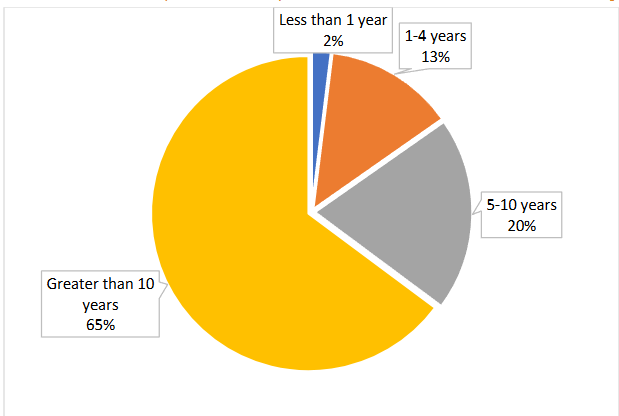

Most participants had been in practice for longer than 10 years after completing training.

Participant Practice Characteristics

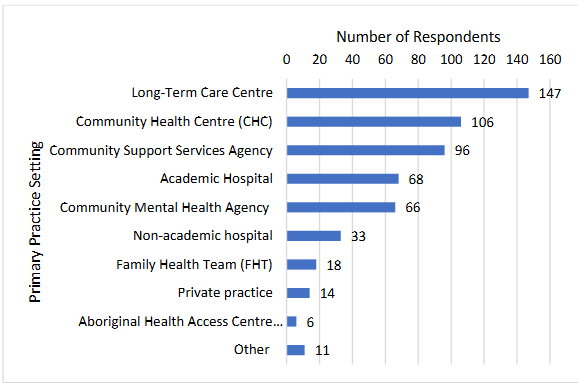

A total of 565 participants provided information about their practice environment and characteristics. National ECHO: COE participants estimated that, on average, 82.7% of their caseload was older adults aged 65 and over. Participants’ most common practice settings were Long Term Care Centres, followed by Community Health Centres, and Community Support Services Agency.

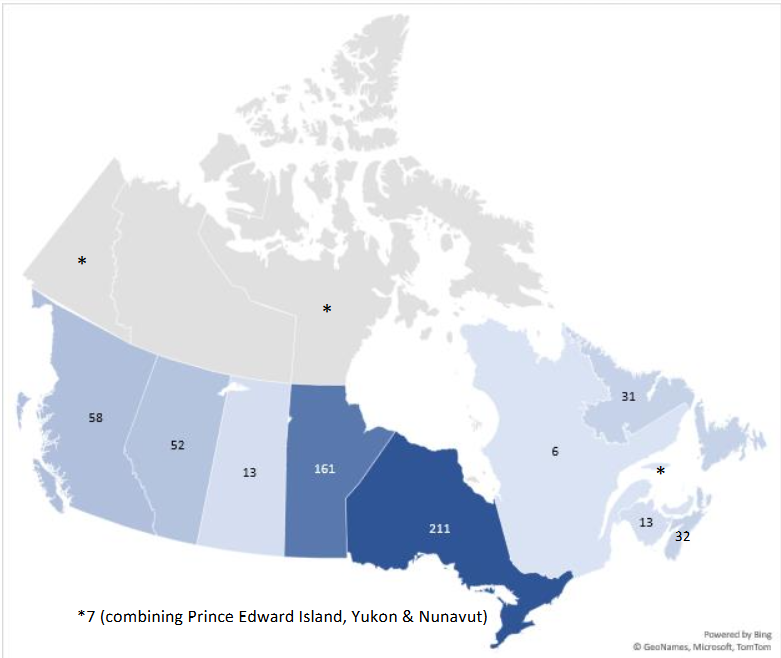

Participants also identified geographic characteristics about their practice, including province and whether their practice environment is considered rural, remote, or urban/suburban. Participants could choose more than one option if they practiced in multiple provinces or practice environments. Participants were spread across regions, with more than one third reporting working in Ontario, and the next most prevalent being Manitoba, then British Columbia, and Alberta.

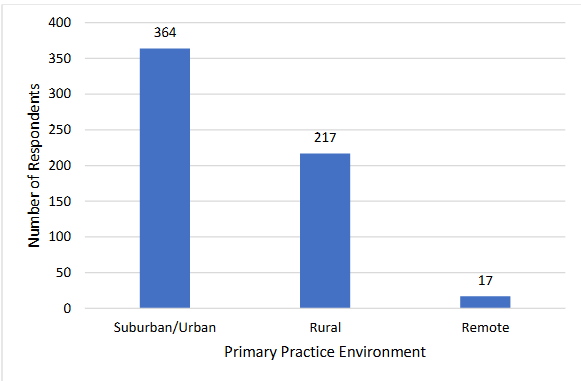

Most participants reported working in suburban/urban settings, followed by rural settings, while only 3.0% reported working in remote settings.

Professional Isolation Perception

Participants were asked, after the last National ECHO: GeMH session, whether participating in the program had an effect on their sense of professional isolation. Of the 269 participants who answered this question across all cycles, 119 (44.2%) selected “Yes” and 150 (55.8%) selected “No.” Of the 119 participants who felt that ECHO did impact their sense of professional isolation, 113 provided usable follow-up comments. Analysis of these comments identified three themes: connection, access to knowledge and expertise, and other comments related to professional isolation. Commenters conveyed that they “feel less isolated … know[ing] that other clinicians are experiencing the same challenges that [they are] experiencing” or that “others are feeling some of the same frustrations with the system.” Some elaborated that this realization was “validating”, fostered a “sense of belonging” or made them feel “less alone.” Notable quotes from commenters include:

“Also, the challenges they encounter on a daily basis which I believe is what I encounter as well and it [gives] me a sense of ‘belonging’ meaning, I am not alone in what I do and I’m not the only person who encounter[s] such challenging situation/s.”

“It has been very validating to recognize that many of the challenges are the same, regardless of where people are practicing.”

Several participants mentioned being “more willing to reach out to others with questions” or connect with others, after participating in ECHO. One commenter summarized their experience as follows:

“The case presentations at the end of each session showed me that professionals across the country are facing similar challenges and showed the importance of reaching out to teammates/other professionals for advice/ideas to assist in challenging situations.”

A small number of participants mentioned that they discussed their ECHO learnings with colleagues after the sessions, and a few mentioned “networking” or feeling “more connected”, without elaborating further. Some commented on a sense of feeling “connected to a larger network of colleagues through a common purpose” or that it is “inspirational to hear how many are continuing to pursue new interventions to better aid their client” or “reassuring that we are doing the right things.” There were comments about “support and professionalism” and appreciation for “weekly interaction” or being “able to connect with others and have the opportunity to discuss points of view,” and that “there are so many others across the country who are in positions similar to [theirs] that are doing great work.” A “lack of mental health support, geriatric support in [a participant’s] community” was also noted. One commenter summarized their experience with the program by saying:

“I must say that participating in this ECHO learning provided a sense of collaboration and a shared goal in enhancing the lives of those we support. Many of us are experiencing the same emotions and seeing the same trends and patterns. It was inspiring to be a part of something like this.”

Many of those who provided comments about ECHO’s impact on professional isolation spoke about access to knowledge or expertise. Comments noted the diversity in both expertise and geographic range of professionals that they had access to in ECHO. They appreciated the opportunity to “hear from those around the province” and also “learn about interprovincial programs.” Others highlighted the “wonderful range of disciplines” and of other professionals they encountered, including geographic diversity “from around the country”, or “other experienced disciplines” or that “it was lovely discussing cases with a multidisciplinary group.”

“From a country wide lens, I love hearing about other programs, interventions, and unique situations that my colleagues are living every day. It helps keep things in perspective and give me joy to hear of the ‘smart thoughts’ which continue to emerge given these very individual situations.”

“It is refreshing to connect with over 100 professionals and seeing that our approach are very similar in how we care and support the elderly across Canada. It was also good to hear about programs in other provinces that are similar or same as what we have in my province. So, I feel that we are on the right track of caring for our elderly.”

“The opportunity to talk with others, hear cases similar to my clients and the HCP challenges to provide the best care for these clients is widespread…Speaking out with multiple disciplines and hearing different perspectives helps to kickstart the problem solving in our own professional strategies.”

Burnout Frequency

Participants were asked before the start of an ECHO cycle, and again shortly after the last session for that cycle, how often over the past month they had experienced burnout. Burnout frequency was rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). A total of 258 participants responded both pre- and post-ECHO. Comparison of overall means over time indicated no significant difference between pre- and post-ECHO estimates of how frequently participants experienced burnout.

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Test Statistic (Degrees of Freedom) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ECHO | 2.85 | 0.99 | ||

| Post-ECHO | 2.88 | 1.02 | ||

| Difference | 0.03 | 0.05 | F (1,257)=0.31 | 0.58 |

There were also no statistically significant interactions between pre- and post-ECHO frequency of burnout and practice environment or geographic region.

Burnout Perception

When asked at the conclusion of the National ECHO: GeMH program if participating in the program impacted their feelings of burnout, 270 participants responded across all cycles. The majority (219, 81.1%) answered “no.” Of the 51 respondents (18.9%) who answered “yes”, 43 provided usable follow-up comments. Once again, thematic analysis reinforced the themes of connection, access to knowledge and expertise, and other comments related to burnout. Almost half of these spoke of a sense of connection with other care providers. Many commenters shared thoughts about feeling “validated in the challenges [they are] experiencing working with clients”, “a bit better that [they are] not the only one[s] feeling this way as a professional working with client[s]” or “not the only one facing challenges with resources.” One participant commented:

“It gave me more energy as I know that other professionals struggle as well in bigger cities than mine with resources at their finger tips. What I am feeling is not just isolated to myself.”

Other feedback related to connection focused on shared experience, support, or other comments each provided by one or two individuals, and these included: a recognition that there are others to connect with; feeling “less isolated”, having a sense of “hope” or feeling “energized” and “validation” for one’s “own approaches.” A few participants mentioned being “more willing to reach out to others with questions” or connect with others, after participating in ECHO. One commenter shared that:

“The series helped me feel energized again about ensuring that health care providers are providing quality dementia care not just to the client but also their support network, and the health care team.”

Many participants also spoke about the value of National ECHO: GeMH in providing them with access to knowledge or expertise. They shared their appreciation for access to “good knowledge”, “tools and different perspectives”, “solutions”, “new ideas and insights”, and “the excitement of new information and wanting to try to do things differently.” One also mentioned the value of ECHO in managing burnout by “knowing that a collective debrief is a week or less away.”

Discussion

Burnout and professional isolation are complex concepts influencing the mental wellness of healthcare workers, with many potential contributing causes. As such, a variety of interventions may be effective in addressing or mitigating burnout and professional isolation, such as support groups, online training programs, or online assessment tools. Of interest for the present work was whether participating in a clinically focused community of practice, distinct from a support group or other targeted mental health intervention, positively impacted perceptions of burnout and professional isolation among a pan-Canadian group of interprofessional HCPs working with older adults.

In the present work, participating in National ECHO: GeMH did not impact participants’ self-reports of how often they experienced burnout; there was no significant change in frequency from pre- to post-ECHO scores. There was also no significant relationship between burnout frequency and participants’ geographic region or the urban/suburban/rural/remote nature of their practice environment. This is likely because burnout is such a complex experience, influenced by many factors which were not addressed in the National ECHO program. It is also possible that a Likert-scale measurement asking participants to rate frequency of burnout is not a sensitive-enough measure to capture the experience or evaluate change over time, or that an 8-10 week program was too brief to produce measurable changes in burnout. There are more common tools in the literature to measure burnout, such as the validated Maslach Burnout Inventory. If burnout becomes a primary focus of our future work, we plan to choose a more robust and validated measure to evaluate it.

There was also no significant relationship between the proportion of participants who reported that ECHO impacted their sense of professional isolation and the geographic region in which participants lived or the urban/suburban/rural/remote nature of their practice environments. This contrasts with other published work about the project ECHO model showing the model makes meaningful contributions to participants’ feelings of professional connection and community. Again, we suggest that a single question may not have been sufficiently valid to capture the complexity of participants’ experience with professional isolation and not sensitive enough to detect subtle changes over the course of the 8 to 10 week program.

Similar to burnout, mitigating feelings of professional isolation may require long-term participation and sustained engagement. Future work could consider a more thorough assessment of both professional isolation and burnout using validated outcome measures, structured interviews, or focus groups.

Despite the lack of significant findings in the quantitative data, however, participants’ comments and feedback suggest that they benefitted from participating in the National ECHO: GeMH program. Analysis of this qualitative data spoke to themes of connection and access to valuable knowledge or expertise. Participants provided thoughtful feedback and examples of how feeling more connected and having increased access to professional resources helped with their feelings of both burnout and professional isolation. It is possible that there is a lagging effect, where perceptions of connection precede measurable changes in burnout or professional isolation; the qualitative findings in the present work hint at changes in connection, knowledge and access, which may be the mechanisms underlying potential future measurable changes in burnout or professional isolation. Overall, the data reinforce that the program was useful and valuable, but that value was not adequately captured in the present program evaluation.

Burnout and professional isolation, although sometimes related, are distinct constructs. While both may be impacted by workplace relationships and access to knowledge and resources, each is also influenced by many other factors which may be beyond individuals’ control. While the qualitative data confirms that the National ECHO: GeMH program successfully enabled participants to access a professional network and resources such as knowledge and expertise, the program could not address all of the factors that influence the complex constructs of professional isolation and burnout. An ECHO program to increase clinical capacity may have greater influence on burnout and professional isolation when coupled with other interventions or supports, for example measures to address workload concerns.

In the present study, we were able to pool data from four different National ECHO: GeMH modules to achieve large overall sample sizes, but under-representation from certain provinces and territories and from remote practice environments meant that data needed to be pooled to conduct the sub-analyses. Efforts were made to ensure that the resultant groups shared the characteristics of interest; for example, participants who worked in remote areas were grouped with those in rural communities, but analyses and conclusions could be strengthened with targeted recruitment to increase sample sizes from under-represented provinces and practice environments. It is also possible that self-selection bias influenced the results of the present study, as people who have access to channels to find out about and participate in these types of programs may already have been less professionally isolated than others.

Conclusion

Overall, National ECHO: GeMH program was designed to build clinical skills and capacity to care for older adults with mental health concerns. Addressing burnout and isolation among providers was a secondary question, and our findings of positive secondary impacts on participants are important to keep healthcare professionals engaged in educational programming and to entice them to continue participating.

References

- Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211.

- Kutoane M, Brysiewicz P, Scott T. Interventions for managing professional isolation among health professionals in low resource environments: A scoping review. Health Sci Rep. 2021;4(3):e361.

- Frey JJ 3rd. Professional loneliness and the loss of the doctors’ dining room. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(5):461-463.

- Reith TP. Burnout in United States healthcare professionals: A narrative review. Cureus. 2018;10(12):e3681.

- Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):475-482.

- Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Hoogduin K, Schaap C, Kladler A. On the clinical validity of the maslach burnout inventory and the burnout measure. Psychol Health. 2001;16(5):565-582.

- Congiusta S, Ascher EM, Ahn S, Nash IS. The use of online physician training can improve patient experience and physician burnout. Am J Med Qual. 2020;35(3):258-264.

- Meese KA, Boitet LM, Sweeney KL, Rogers DA. Perceived stress from social isolation or loneliness among clinical and non-clinical healthcare workers during COVID-19. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):1010.

- Cotobal Rodeles S, Martín Sánchez FJ, Martínez-Sellés M. Physician and medical student burnout, a narrative literature review: Challenges, strategies, and a call to action. J Clin Med. 2025;14(7):2263.

- Sockalingam S, Clarkin C, Serhal E, Pereira C, Crawford A. Responding to health care professionals’ mental health needs during COVID-19 through the rapid implementation of project ECHO. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2020;40(3):211-214.

- Atanackovic J, Corrente M, Myles S, et al. Cultivating a psychological health and safety culture for interprofessional primary care teams through a co-created evidence-informed toolkit. Healthc Manage Forum. 2024;37(5):334-339.

- Projectecho B. Project ECHO: Origin Story. Project ECHO. July 14, 2025. Accessed July 31, 2025. https://projectecho.unm.edu/story/project-echo-origin-story/

- Arora S, Kalishman SG, Thornton KA, et al. Project ECHO: A Telementoring Network Model for Continuing Professional Development. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2017;37(4):239-244.

- Furlan AD, Pajer KA, Gardner W, MacLeod B. Project ECHO: Building capacity to manage complex conditions in rural, remote and underserved areas. Can J Rural Med. 2019;24(4):115-120.

- Chicoine G, Côté J, Pepin J, et al. Effectiveness and experiences of the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) Model in developing competencies among healthcare professionals: a mixed methods systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):313.

- Zhou C, Crawford A, Serhal E, Kurdyak P, Sockalingam S. The Impact of Project ECHO on Participant and Patient Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1439-1461.

- Lingum NR, Sokoloff LG, Meyer RM, et al. Building Long-Term Care Staff Capacity During COVID-19 Through Just-in-Time Learning: Evaluation of a Modified ECHO Model. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(2):238-244.e1.

- Lingum NR, Sokoloff LG, Chau J, et al. ECHO care of the elderly: Innovative learning to build capacity in long-term Care. Can Geriatr J. 2021;24(1):36-43.

- Adams MS, Sokoloff LG, Checkland C, et al. Evaluating the impact of a national geriatric mental health ECHO educational program on healthcare providers’ practice. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. Published online April 22, 2024:1-15.

- Agley J, Delong J, Janota A, Carson A, Roberts J, Maupome G. Reflections on project ECHO: qualitative findings from five different ECHO programs. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1936435.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381.

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. SAGE; 2011.

- Bursch B, Emerson ND, Arevian AC, et al. Feasibility of online mental wellness self-assessment and feedback for pediatric and neonatal critical care nurses. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;43:62-68.

- Zhao QJ, Rozenberg D, Nourouzpour S, et al. Positive impact of a telemedicine education program on practicing health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada: A mixed methods study of an Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) program. J Telemed Telecare. 2024;30(2):365-380.

- Bikinesi L, O’Bryan G, Roscoe C, et al. Implementation and evaluation of a Project ECHO telementoring program for the Namibian HIV workforce. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1):61.