Impacts of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination and Infection

Compound Impacts of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Convergence of Diverse “Spikeopathies” and Other Hybrid Harms

M. Nathaniel Mead, Jessica Rose, Stephanie Seneff, Claire Rogers, Nicolas Hulscher, Kirstin Cosgrove, Breanne Craven, Paul Marik, Peter A. McCullough

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED 30 November 2025

CITATION Mead, MN., Rose, J, et al., 2025. Compound Impacts of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Convergence of Diverse “Spikeopathies” and Other Hybrid Harms. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(11). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i11.7087

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i11.7087

ISSN 2375-1924

KEYWORDS: vaccines, vaccination, modified mRNA products, SARS-CoV-2 infections, post-COVID vaccination syndrome, adverse events, immune dysfunction.

ABSTRACT

COVID-19 can have short- and long-term health consequences, including various cardiovascular, respiratory, hematologic, autoimmune, and neurological conditions. Although it is often claimed that COVID-19 mRNA vaccinations reduce COVID-19 severity and post-acute sequelae, these assertions are refuted by evidence of extensive mRNA immunization-related harms that appear to be amplified by SARS-CoV-2 infection, resulting in considerable overlap in reported adverse outcomes. Spike proteins from both sources persist in the human body over the long-term, leading to immune dysfunction, inflammation, autoimmunity, organ dysfunction, and overlapping toxicities. We hypothesize that the mRNA vaccinations create a persistent toxic milieu of spike protein, inflammatory lipid nanoparticles, and DNA impurities, amplifying morbidity and mortality risks commonly ascribed to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Many 2021-2024 morbidity/mortality events in highly vaccinated populations, though often attributed solely to COVID-19 illness (due to close temporal associations with laboratory-confirmed infection), were more likely to result from these interactions or “hybrid harms”. Evidence supporting our hypothesis includes studies of negative efficacy, overlapping pathologies (e.g., myocarditis and thrombosis), redundant mechanisms, and epidemiological surges in excess mortality during the Omicron era (since December 2021) in extensively vaccinated countries. Case report data indicate that spike protein production along with associated “spikeopathies” may persist for at least three years, during which a coronavirus infection could trigger a new disease syndrome that would logically be attributed to the infection based on the timing. In contrast there is a relatively mild course for Omicron infections in the unvaccinated. Ongoing spike production from prior mRNA vaccinations is likely to predispose Omicron-infected individuals to cumulative adverse effects over time. The amplified toxicities and immunopathologic effects may help account for near-synchronous waves of COVID-19 and all-cause mortality in the Omicron era. This novel framework calls for re-examining the unique immunopathological consequences of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection in COVID-19 mRNA-vaccinated individuals and consideration of the implications for future public health strategies.

Introduction

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in early 2020 led to hundreds of millions of confirmed infections and a substantial global mortality burden. Early deaths were largely attributed to uncontrolled viral replication and maladaptive immune responses in vulnerable groups, particularly the elderly and individuals with comorbidities such as vascular diseases, chronic respiratory conditions, malignancies, obesity, and diabetes. By December 2020, the modified mRNA vaccines, BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna), had received emergency use authorization after only 2-3 months of randomized trial data collection. Previous timeframes for testing the safety and efficacy of vaccines were on the order of 10-15 years.

These injectable products use synthetic mRNA to direct host cells to produce the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, essentially functioning as prodrugs that induce endogenous antigen production to stimulate antibody and T-cell responses. While typically referred to as vaccines, their mechanism aligns more closely with gene transfer technology, making the terminology “gene transfer products” more precise. (As a compromise, we will use the more common terms vaccine and vaccination in this review.)

Despite the worldwide vaccination campaign and declaration by the World Health Organization (WHO) announcing the end of the COVID-19 “global health emergency” in May 2023, COVID-19 remains a significant concern: the disease persists as an ongoing global health challenge, with recurring outbreaks and disproportionate impacts on vulnerable populations. WHO data show documented >10% case increases in 37 countries overall, with 15 countries showing rising hospitalizations, mainly in Europe and the Americas. A recent review noted “millions of cases and thousands of [COVID-19] fatalities being recorded every month”, and also cites reports of adverse events (AEs) associated with the mRNA vaccinations, including autoimmune conditions, thrombotic events, myocarditis, pericarditis, stroke, and renal disease. A Swiss report projected excess all-cause mortality of up to 2.5% in the United Kingdom and 3% in the United States by 2033 (excess mortality is normally at 0%). Over 7.1 million “COVID-19-associated deaths” were reported worldwide as of September 2025.

COVID-19 mortality estimates are controversial, however, mainly due to heavy reliance on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, rather than direct viral culture. RT-PCR testing can overstate COVID-19 incidence by detecting non-infectious viral RNA, contributing to a substantial percentage of false positive or clinically meaningless results, while simultaneously understating prevalence due to limitations in testing access, timing, and sensitivity to low viral loads. The test’s high sensitivity may also amplify residual RNA from past infections or low viral loads that do not indicate active disease. Moreover, RT-PCR testing can contribute to overestimating COVID-19 mortality by detecting viral RNA in asymptomatic or non-causal cases, leading to incidental positive results and inflating mortality estimates. The extent of overestimation depends on testing practices, clinical context, and how deaths are attributed. A study analyzing 530 “COVID-19 deaths” in seven Greek hospitals in Athens from January to August 2022 found that only 25.1% were directly caused by COVID-19, with 29.6% involving the coronavirus as a contributing factor, while 45.3% of deaths among patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were unrelated to the virus. COVID-19 death counts in elderly populations are especially prone to overestimation, due to higher baseline mortality rates.

The emergence of the Omicron variant in November 2021 marked a turning point. Omicron demonstrated higher transmissibility and immune evasion but substantially lower intrinsic pathogenicity than Delta, with reduced lung replication, less severe clinical presentations, and lower case-fatality rates. Initial data suggested that Omicron infections were typically mild and self-limiting, resembling mild influenza or the common cold for the majority of infected individuals. Animal models and human data consistently show Omicron subvariants result in milder disease when compared to the Delta variant, with reduced lung pathology and hospitalization risks. The overall scientific consensus is that Omicron evolved toward higher transmissibility but also much lower intrinsic pathogenic potential.

Nonetheless, studies of excess mortality in 2021–2023 revealed paradoxical increases in COVID-19 mortality, non-COVID mortality, and all-cause mortality during Omicron waves, even in countries with high vaccination rates. In 2022, the heavily vaccinated populations of South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Australia, exhibited pronounced peaks in percent excess mortality (PEM), closely synchronized with the Omicron waves. Japan and Thailand also experienced all-cause mortality spikes that coincided with Omicron peaks. Thus, despite Omicron’s milder nature, many extensively mRNA-vaccinated countries showed more substantial excess mortality in concert with surges in Omicron incidence.

These observations raise important questions. To what extent are ongoing COVID-19 fatalities attributable to Omicron infection itself, to artifacts of testing, or to complex interactions between vaccination and infection? Official justifications for mass vaccination emphasized its putative role in reducing severe outcomes and achieving herd immunity. However, risk-benefit analyses often rest on the assumption that mRNA injection-induced spike protein expression is transient. Evidence now suggests that spike production, and associated pathophysiological effects (“spikeopathies”), may persist for extended periods, perhaps indefinitely. This persistence could modify the clinical course of subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infections, amplifying disease severity and increasing the risk of premature death.

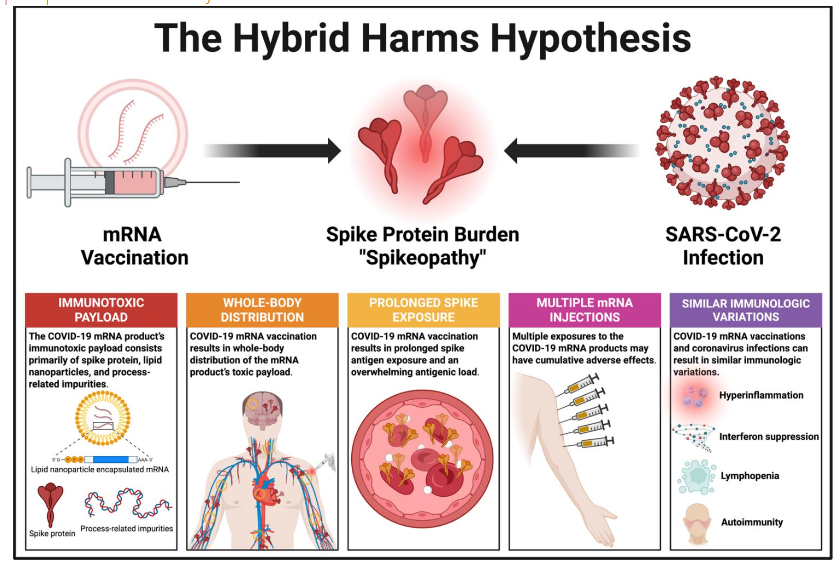

The Hybrid Harms Hypothesis

Before introducing our hypothesis, we must refute the claim that the mRNA vaccinations prevent severe disease, hospitalization, and death. This claim is contradicted by evidence of negative efficacy and absence of support from sufficiently powered, randomized controlled trials. While some studies suggest very short-lived protection against infection but stable protection against severe outcomes, methodological flaws—such as inconsistent follow-up, selective exclusion, and case-counting window bias—undermine claims of protection.

For example, a large Italian study misclassified AEs post-vaccination, skewing results. In the Pfizer trial, severe disease among infected individuals occurred in 12.5% of the mRNA vaccine cohort, as opposed to only 5.6% in the placebo cohort. A meticulous 2023 review found no robust evidence that mRNA boosters effectively prevent severe illness or mortality and identified multiple biases inflating efficacy estimates.

Other analyses further bolster the case for negative efficacy. A Cleveland Clinic study (n=51,017) found infection risk rising in a linear fashion with each successive mRNA dose, while unvaccinated employees with prior exposure showed no reinfections over five months. Similarly, Japanese case-control data reported a mRNA dose-dependent rise in infection risk, with odds ratios climbing from 1.85 (1–2 doses) to 2.21 (5–7 doses). Findings from Qatar, the UK, Iceland, Israel, and multiple U.S. datasets confirm elevations in infection rates post-mRNA vaccination versus no vaccination. A large Israeli cohort study reported a 27-fold higher risk of symptomatic COVID-19, along with an eight-fold higher hospitalization rate in BNT162b2-injected versus unvaccinated controls. Data from the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) as of November 2024 show a dose-dependent rise in BTIs, with a 30% elevation after the fourth dose compared to 16% after the third. Collectively, these findings suggest that mRNA vaccinations may, contrary to the prevailing narrative, increase severe disease risk among infected individuals.

Against this backdrop, the Hybrid Harms Hypothesis states that prolonged and repeated spike antigenic exposures via mRNA vaccination may interact with either a previous or subsequent coronavirus infection, producing adverse effects. This interaction results in an amplification of “spikeopathy”, manifesting as chronic spike protein toxicity, immune dysfunction, persistent inflammation, and diverse pathological sequelae, including many disease and disability events that have been associated with both the COVID-19 vaccinations and coronavirus infections. In the case of post-vaccination infections, the apparent temporal association between the diverse sequelae and the SARS-CoV-2 infection has often resulted in systematic misclassification, attributing causality solely to the viral infection rather than considering the potential background context of spike protein generated by previous mRNA vaccinations.

Medical editorials have often claimed that “breakthrough” SARS-CoV-2 infections are “rare and mild” in vaccinated people. However, the mRNA vaccinations exhibit rapid waning of humoral immunity, with neutralizing antibody levels declining sharply within 2-6 months, exacerbated by immune imprinting and viral mutations. This contributes to widespread breakthrough infections (BTIs), defined as infections ≥2 weeks post-vaccination, which may have affected 40-45% of vaccinated cohorts since 2021. Contrary to the aforementioned editorial claims, BTIs are often associated with worse outcomes, including severe or critical illness in ~11% of cases, linked to comorbidities like cardiovascular disease, and mortality rates around 0.9%—substantially higher than the 0.03-0.05% infection fatality rate for natural SARS-CoV-2 infections in similar populations. Population-level data from the UK reveal significant BTI deaths, such as 43% of Delta variant fatalities in fully vaccinated individuals by mid-2021, with 60% of fatalities having received at least one mRNA injection. The true extent of BTI mortality in many countries has likely been underestimated due to biases in reporting, restrictive definitions, and financial/political pressures to promote vaccine efficacy.

The official rationale underlying the claim that BTIs are beneficial rather than harmful is that the vaccination is priming the body’s immune memory, theoretically enabling more effective control of viral replication. Nevertheless, there is substantial evidence that BTIs can result in severe disease and death in COVID-19 mRNA-injected individuals who are considered “fully vaccinated”. Consider the following anecdotal examples of this phenomenon from media reports:

Case 1: A robust, physically fit 21-year-old male college student, fully vaccinated against COVID-19, is subsequently diagnosed with the disease. Over a six-week period, he is hospitalized multiple times and dies after extensive medical interventions.

Case 2: A 36-year-old male flight attendant, known for meticulous adherence to infection prevention measures, contracts COVID-19 following full mRNA vaccination. His illness requires hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, and ultimately proves fatal.

Case 3: A 33-year-old female from Louisiana, fully vaccinated against COVID-19, develops a rapidly progressing illness, leading to her death just four days after symptom onset. Doctors speculate that her extremely rapid demise may be related to her obesity.

In each of these cases, COVID-19 was cited as the official cause of death. We hypothesize, however, that COVID-19 was only the final phase in the etiologic chain of events, and that the preceding full course of COVID-19 mRNA vaccinations represented the initial immunotoxic insult that predisposed each individual to more severe morbidity and, ultimately, to premature death.

The Hybrid Harms Hypothesis is distinguished by five fundamental features: (1) the COVID-19 mRNA product’s three-pronged toxic payload; (2) whole-body biodistribution; (3) multiple mRNA injections; (4) prolonged exposure to the mRNA product’s payload; and (5) infection with SARS-CoV-2 or Omicron variants, either sometime before or months to years after the vaccination, in which case the disease symptoms may often be misattributed to the viral infection and its “Long Covid” sequelae. Let us now consider each of these and their relevance to our hypothesis.

Hybrid Harms Feature #1: Immunotoxic Payload

The mRNA products contain three primary sources of toxicity: spike protein, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), and process-related impurities. Spike protein has inherent pathogenic potential regardless of whether it comes from the infection or injection. The pathophysiological effects relate to oxidative stress, endothelial damage, thrombogenesis, inflammation, and prion-like dysregulation. Spike protein can damage endothelial cells by downregulating ACE2 and consequently inhibiting mitochondrial function. Certain genetic polymorphisms may heighten susceptibility to serious AEs, including sudden death, autoimmune disorders, and cancers.

LNPs, the delivery system for synthetic mRNA, amplify inflammation by stimulating cytokine release, activating toll-like receptors, and triggering the NLRP3 inflammasome. Ionizable lipids are intrinsically immunotoxic, while prior exposure in mice showed lasting suppression of adaptive immunity. These effects may be magnified in individuals with chronic diseases that have an inflammatory component (e.g., obesity, diabetes, heart disease), as well as in those with age-related, low-grade inflammation, also known as “inflammaging”.

Process-related impurities pose as a third hazard. Manufacturing introduces billions of plasmid-derived DNA fragments into each dose, often greatly exceeding regulatory thresholds. Plasmid DNA contaminants in Pfizer’s Comirnaty exceeded acceptable limits by hundreds of times, in some samples by over 500-fold. Encapsulated within LNPs, these contaminants (e.g., fragments of plasmid cDNA coding for SV40) may integrate into the human genome, raising concerns about insertional mutagenesis, autoimmunity, and oncogenesis. Florida Department of Health data show higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality following Pfizer’s BNT162b2 than Moderna’s mRNA-1273, a divergence plausibly linked to Pfizer’s higher DNA contamination levels. BNT162b2 also induced higher IgG2 and IgG4 subclass switching, potentially increasing risks of infection, autoimmune disease, and cancer.

Hybrid Harms Feature #2: Whole-Body Distribution

Animal biodistribution studies reveal that LNP-encapsulated synthetic mRNA disperses widely, crossing the blood-brain and placental barriers and concentrating in liver, spleen, ovaries, adrenal glands, testes, heart, brain, uterus, spinal cord, thymus, pituitary, eyes, and bone marrow. This systemic delivery contrasts with natural infections, where tropism is tissue-specific. Such systemic distribution underlies the wide spectrum of AEs, including myocarditis, hepatitis, ovarian dysfunction, and neuroinflammation. The spike protein disrupts brain endothelial cells, compromising the blood-brain barrier and contributing to direct neuroinflammatory and neurotoxic effects. Frameshift mistranslation of pseudouridinated mRNA may produce aberrant proteins forming prion-like fibrils. Although prion diseases primarily affect the central nervous system, causing neurodegenerative conditions, prions can also spread to other tissues, such as lymphoid organs, sometimes resulting in systemic involvement. Otherwise rare prion diseases have indeed been increasingly reported since 2021, with symptom onset often observed within days of COVID-19 vaccination.

Hybrid Harms Feature #3: Prolonged Spike Exposure and Antigenic Load

Stability of the mRNA product is enhanced by LNP encapsulation and substitution of uridine with N1-methylpseudouridine, which minimizes degradation of the synthetic mRNA, thus ensuring the spike protein’s persistent bioavailability for an unknown period of time. This is contrary to initial assumptions of rapid clearance after only 1-2 weeks. Early studies demonstrated persistence of detectable spike protein for 1-2 months. When observational timeframes were further lengthened, analyses revealed spike in circulation for 6-8 months, and subsequently for 17-24 months. The latest case report showed circulating vaccine mRNA 3.2 years post Pfizer vaccination. These findings suggest that the modified mRNA effectively converts cells into viral protein factories that lack an “off switch” mechanism for halting the generation of the spike antigen. The main concern is that ongoing spike production, and the resulting cumulative antigenic load, may lead to systemic inflammation, immunologic dysfunction, and potentially a host of immune-related disorders over the long term.

Additionally, the N1-methylpseudouridine modification enhances transcriptional infidelity by promoting ribosomal miscoding, leading to elevated rates of amino acid misincorporation and a higher frequency of translation errors. Even minor inaccuracies in transcription can result in incorrect amino acid sequencing during protein translation. The proteins synthesized may be dysfunctional or excessively immunogenic, thereby triggering autoimmunity or other pathological effects (e.g., cellular dysfunction or disease). Such errors also raise concerns about the long-term safety of the COVID-19 mRNA injections, including the potential for catastrophic effects when scaled to large populations over time.

Hybrid Harms Feature #4: Cumulative Impact of Repeated Exposures

Repeated administration of the modified mRNA injectables appears to increase the risk of infections as well as autoinflammatory phenomena associated with COVID-19 mRNA-induced damage to the heart, brain, and other organs. Successive doses of these mRNA products may increase the likelihood of acute de novo immune thrombocytopenic purpura and other serious hematologic events in previously healthy individuals. Repeated vaccination also drives T-cell exhaustion and IgG4 class-switching. Studies show reduced T-cell responses within a month of booster doses, accompanied by rising IgG4, an antibody subclass linked to immune tolerance.

The IgG4 class switch is linked to the reduced T-cell response after three to four doses (first and second boosters) of the COVID-19 mRNA product. Elevated IgG4 correlates with higher rates of BTIs, further suggesting that repeated boosters undermine rather than enhance immunity. Timing of infection relative to vaccination further alters outcomes. In individuals infected after mRNA vaccination, IgG4 responses matched or exceeded IgG1, shifting immunity toward tolerance. The findings suggest that initial immune priming via the mRNA vaccination, if followed by SARS-CoV-2 infection, may significantly alter the humoral response, potentially leading to increased production of IgG4 antibodies and a heightened risk of infection, cancer, and autoimmune disease.

Hybrid Harms Feature #5: Additive and Synergistic Effects with Infections

The mRNA injections and coronavirus infections elicit overlapping immunologic responses, raising the possibility of additive or synergistic harms. What follows are the main examples from a pathophysiological perspective:

Hyperinflammation: The mRNA vaccination elicits production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, activation of cell-mediated immunity, and autoimmune-inflammatory disorders. Similarly, severe COVID-19 is often characterized by hyperinflammation and lung-damaging cytokine storms. Given that the interaction may intensify respiratory failure or other systemic inflammation, the question may be asked: How many ICU cases involving severe COVID-19 pneumonia were exacerbated by prior mRNA vaccinations?

Autoimmunity: Both infection and vaccination have been linked with new-onset autoimmune conditions, plausibly through molecular mimicry, epitope spreading, and bystander activation. Severe SARS-CoV-2 infections are associated with new-onset autoimmune conditions such as cutaneous vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa, and immune-related hepatitis. The mRNA vaccinations can cause rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, and autoimmune hepatitis, among other autoimmune disorders. The convergence of these exposures may accelerate autoimmune disease incidence.

Lymphopenia: Lymphopenia can boost the risk of infections and is nearly universal in severe COVID-19 cases. COVID-19 severity is associated with functional exhaustion of T-lymphocytes, most often following T cell hyperactivation in earlier disease stages. Similar T-cell reductions have been observed after multiple mRNA vaccinations. When combined, severe COVID-19 and multiple mRNA doses would further deplete T cells, leaving patients more vulnerable to infections.

Interferon Suppression: Low levels of interferon, a pleiotropic cytokine that regulates the immune response and inflammation, is common in severe COVID-19. Autoantibodies against type I interferons underlie COVID-19 pneumonia and are found in many patients with life-threatening COVID-19 when compared to healthy controls. Conversely, the mRNA vaccinations can induce anti-interferon autoantibodies even in healthy individuals. BNT162b2-induced suppression of antiviral defenses, along with direct spike-mediated cardiomyocyte damage, could contribute to “viral” myocarditis.

Together, these phenomena blur the boundary between COVID-19 morbidity and mRNA vaccine-related pathology. The spike protein remains the unifying antigenic trigger across both contexts, and its persistence magnifies the likelihood of overlapping harms.

Hybrid immunity versus hybrid harms: an immunologic paradox

Once it became clear that the mRNA products could not provide durable sterilizing immunity, a new rationale emerged, one centered around the concept of hybrid immunity: the enhanced immunological responses resulting from the combined exposure to mRNA vaccination and the infection, producing stronger immunity when compared to either exposure alone. Individuals with recent SARS-CoV-2 exposure who have undergone mRNA vaccination exhibit a more robust and diverse antibody repertoire, characterized by elevated neutralizing antibody titers and a broader spectrum of epitope recognition.

This “enhanced” humoral immunity has been associated with a 5- to 10-fold increase in memory B cell populations when compared to infection or vaccination alone. In short, mRNA vaccination following infection does generate a stronger immune response, with the timing of the prior infection (rather than its severity) largely determining post-vaccination IgG levels. In addition, previously-infected individuals have stronger T-cell responses after each mRNA vaccine dose compared to never-infected mRNA vaccine recipients.

Currently, in populations with high vaccination coverage, a substantial proportion of individuals have developed hybrid immunity rather than “natural” immunity, i.e., non-vaccinated immunity to SARS-CoV-2. A prospective, multi-regional cohort investigation conducted in Switzerland reported that, as of July 2022, a minimum of 51% of participants possessed hybrid immunity, while 85% demonstrated detectable levels of Omicron-targeted neutralizing antibodies. By 2023, widespread Omicron exposure suggested that most inhabitants of developed nations likely had been exposed to both virus and vaccine, thus had hybrid immunity.

Before addressing the hybrid effects, note that the mRNA vaccine-induced spike protein, combined with other components in the formulation, appears to elicit a far stronger and more narrow immune response compared to the native coronavirus spike protein. Indeed, individuals who were up-to-date with their COVID-19 vaccinations showed an average of 50 times greater antibody levels than unvaccinated, coronavirus-infected persons. The hybrid immunity afforded by the vaccination-infection interaction would further bolster the humoral immune response in the vaccinees, as indicated by even higher antibody titers. While having higher antibody titers might seem like a worthwhile clinical goal, the amplified humoral response is associated with increased risks of hyperinflammation, severe immunopathology, and heightened reactogenicity, all of which may contribute to diverse AEs following mRNA vaccination.

Dosing per injection helps further illustrate this concern. Moderna’s mRNA-1273 includes 100 μg of mRNA, whereas Pfizer’s BNT162b2 incorporates 30 μg of mRNA. The higher dose in mRNA-1273 correlates with a stronger humoral response, including higher levels of spike-specific opsonophagocytic antibodies, NK cell-activating antibodies, and NTD-specific Fc-receptor binding antibodies. These results may account for the Moderna product’s purported ability to produce lower rates of symptomatic infection when compared to BNT162b2. However, the “super-charged” immune response afforded by mRNA-1273 is also accompanied by a higher incidence of serious AEs, as evidenced by clinical trials, observational studies, and government-sponsored surveillance data. A Taiwan study involving 1,711 booster recipients showed that simply switching from Moderna’s product to a different brand lowered the risk of AEs by 18%. A two-year analysis of Moderna’s mRNA-1273, covering over 772 million doses, reported that 0.7% of the more than 2.5 million AEs led to fatalities (~17,500 deaths total).

The explanation for this immune paradox—that more antibodies can backfire biologically—has recently become clearer. For many years, the scientific community has believed that higher antibody levels correlate with stronger immunity against the pathogen targeted by a vaccine. This belief significantly influenced the determination of the mRNA doses in these genetic vaccines, and it is an extension of the observation that survivors of severe COVID-19 exhibited a survival advantage by rapidly generating higher levels of neutralizing antibodies compared to binding (non-neutralizing) antibodies, unlike non-survivors, who produced these antibodies more slowly and at lower levels. Nevertheless, even though antibody generation has been the primary indicator of protection elicited by almost all clinically licensed vaccines, the mRNA vaccine-specific titers by themselves do not necessarily translate into efficacy.

Although neutralizing antibody titers are indeed associated with protection against infection (primarily because they opsonize pathogens, making it easier for macrophages to recognize them), excessive antibody production can have untoward effects such as vaccine-associated enhanced disease (VAED), potentially mediated by the phenomenon of antibody-dependent enhancement or pathogenic priming. To date, this phenomenon has been mainly observed in animal models, with few cases reported in the clinical setting. Excessive non-neutralizing antibody production may increase the risk of autoimmune reactions through molecular mimicry, where antibodies cross-react with host tissues, potentially triggering inflammatory pathologies. Such mechanisms could elevate the risk of chronic inflammatory conditions, including cardiovascular diseases, malignancies, and other autoimmune disorders.

Importantly, such high antibody levels could also inhibit the capacity of the macrophages to phagocytize and destroy pathogens or cancer cells. In principle, this hyperimmune antibody-macrophage interaction would help explain why the hybrid immunity afforded by the combination of the mRNA vaccinations and coronavirus infections may confer protection against the infection while concomitantly increasing the risk of more serious AEs. The trade-off between hybrid immunity’s “enhanced” short-term protection against the coronavirus on the one hand, and increased risks of serious AEs on the other, underscores the need for a more balanced assessment of mRNA products’ safety and efficacy.

Post-Vaccine Syndromes often overlap with “Long COVID”

The phenomenon known as “Long COVID” emerged in 2020 when individuals recovering from SARS-CoV-2 infections began self-reporting persistent symptoms that extended beyond the acute phase, prompting subsequent medical recognition. The more official term, Post-acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC), is a multifaceted condition characterized by persistent symptoms, including severe fatigue, cognitive impairment, myalgia, dyspnea, paresthesia, and thoracic discomfort, often lasting for months. PASC is a multisystemic disorder involving dysautonomia, neuroinflammation, immune dysregulation, cardiovascular and coagulopathic abnormalities, and multi-organ involvement. Although PASC is invariably framed as viral sequelae, comparable syndromes have been documented following vaccination. As we noted previously, spike protein is a shared feature of both coronavirus infection and mRNA vaccinations, and the mRNA vaccinations induce systemic spike protein production for several years post-vaccination. The prolonged presence of spike protein has been detected in individuals with PASC, suggesting a role in perpetuating symptoms.

To explore the relationship between PASC and post-vaccination syndromes, a study of 100 “Long COVID” patients found that vaccinated individuals with PASC had significantly higher SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody levels (average 11,356 U/mL) compared to unvaccinated individuals (1,632 U/mL), despite no recent infections, suggesting mRNA vaccines may increase spike protein burden linked to PASC symptoms. A retrospective analysis showed 70% of PASC cases occurred in fully vaccinated individuals, indicating mRNA vaccines may exacerbate PASC. Unvaccinated individuals with prior Omicron infection had the lowest PASC incidence (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.07–0.25), while vaccination did not reduce PASC risk. A global survey of 7,541 people showed vaccinated males had higher severe PASC outcomes (13.64% vs. 8.34%, HR=1.63) and vaccinated women reported more vaccine-related AEs (60.85% vs. 48.79%) and menstrual disturbances, while men noted hormonal and sexual dysfunction. Pre-existing conditions increased PASC risk.

Such post-vaccination observations led Scholkman to recognize novel post-vaccination syndromes with clinical features overlapping those of PASC. The authors propose the inclusion of a specific diagnostic code for “post-COVID-19 vaccination condition, unspecified” in future iterations of the International Classification of Diseases. Post-COVID-19 Vaccine Syndrome (PCVS) may subsume many cases of PASC.

| Organ system | PASC/PCVS Combined | Organ system | PASC/PCVS Combined |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | ● Acute coronary disease ● Angina ● Atrial fibrillation ● Cardiac arrest ● Cardiogenic shock ● Heart failure ● Ischemic cardiomyopathy ● Myocardial infarction ● Myocarditis ● Nonischemic cardiomyopathy ● Pericarditis ● Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome |

Gastrointestinal | ● Acute gastritis ● Acute pancreatitis ● Cholangitis ● Constipation ● Diarrhea ● Gastroesophageal reflux disease ● Inflammatory bowel disease ● Irritable bowel syndrome ● Liver abnormalities/injury ● Nausea ● Transaminitis ● Vomiting |

| Coagulation/Hematological | ● Anemia ● Coagulopathy ● Deep vein thrombosis ● Immune Thrombocytopenia ● Pulmonary embolism |

Gynecological | ● Menstrual irregularities ● Infertility ● Miscarriage |

| Dermatological | ● Bullous pemphigoid ● Chilblains ● Hair loss ● Herpes zoster ● Skin rash ● Urticaria ● Vitiligo |

Mental Health | ● Depressive disorders ● General anxiety disorder ● Panic disorder ● Suicidal ideation |

| Endocrine | ● Diabetes mellitus ● Thyroid dysfunction |

Musculoskeletal | ● Myalgia ● Myopathy |

| Immunological/Autoimmune | ● Ankylosing spondylitis ● Mast cell activation syndrome ● Multisystem inflammatory syndrome ● Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome ● Reactivated EBV ● Reactivated Lyme ● Rheumatoid arthritis |

Neurological | ● Alzheimer’s disease ● Bell’s palsy ● Dysautonomia ● Dystonia ● Epilepsy & seizures ● Headache & migraine ● Insomnia/sleep disorder ● Ischemic stroke ● Memory problems ● Paresthesia ● Parkinsonian disorders ● Peripheral neuropathy ● Syncope ● Visual abnormalities |

| Otolaryngological | ● Ageusia ● Anosmia ● Dysgeusia ● Hearing loss, Tinnitus ● Vertigo |

Pulmonary | ● Cough ● Dyspnea ● Hypoxemia ● Interstitial lung disease ● Shortness of breath |

| Renal | ● Acute kidney injury ● Chronic kidney disease |

Evidential support for Hybrid Harms

Since May 2021, COVID-19 mRNA vaccination-induced myocarditis has been recognized as a safety concern, with studies showing stronger links to severe cardiac outcomes than SARS-CoV-2 infections, particularly as the virus rarely causes direct cardiotoxicity. The mRNA vaccine-derived spike protein has been found in cardiac tissue post-mortem and in myocarditis cases. Experimental models confirm cardiotoxic effects of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 in rat cardiomyocytes within 48 hours. Post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infections, often occurring after vaccine failure, may exacerbate myocarditis and cardiac issues by priming pathogenic pathways. Subclinical myocardial injury affects about 2.5% of young adults post-vaccination. Cardiac MRI studies indicate subclinical myocarditis rates three times higher than clinically detected cases, resulting in significant underreporting.

In line with our hypothesis, the hybrid exposure heightens risk via persistent mRNA vaccine-derived spike protein combined with infection-induced spike protein, triggering hyperimmune responses. Subclinical myocarditis can produce microscopic fibrosis, which infection later amplifies, increasing susceptibility to arrhythmias, contractile dysfunction, and heart failure. Repeated mRNA doses elevate myocarditis risk, with the second dose associated with 3- to 5-fold increases, particularly among young males. The higher mRNA content of Moderna’s mRNA-1273 compared to Pfizer’s BNT162b2 (100 µg vs. 30 µg, respectively) resulted in a doubling in the myocarditis/pericarditis risk when compared to Pfizer’s BNT162b2, indicating a dose-response relationship.

The following case reports exemplify potential hybrid harms in Pfizer-vaccinated individuals who developed myocarditis after SARS-CoV-2 infection. A previously healthy 26-year-old male developed acute lymphocytic myocarditis with severely reduced left ventricular function eight weeks after infection, having received his second COVID-19 mRNA dose four months earlier. Similarly, a 42-year-old male with a prior history of perimyocarditis (from 2008) experienced Omicron-related myocarditis involving 22% of the left ventricular mass, four months after his third Pfizer mRNA vaccine dose. That same paper describes the case of a 60-year-old male who presented with ventricular tachycardia and acute myocarditis (affecting 19% of the left ventricular mass) following Omicron infection, also four months post his third Pfizer dose.

In these cases, the COVID-19 mRNA vaccination may train the immune system to recognize the spike protein, creating memory T and B cells. Upon encountering the coronavirus, these cells may mount a rapid and robust immune response. In some cases, this heightened activity may inadvertently exacerbate inflammation in the myocardium, particularly if residual inflammation from the mRNA-induced myocarditis has not completely resolved. A subsequent coronavirus infection could restimulate immune cells primed by the mRNA injection or even a preceding initial infection, and the resulting hyperimmune response might disproportionately target cardiac tissue, transforming a subclinical situation into fulminant myocarditis. (Note: The temporality of exposures can also be reversed: the medical literature contains case reports of individuals who first contracted the SARS-CoV-2 infection, then later received the mRNA vaccination before being diagnosed with myocarditis.)

Our critics may point to the large observational study by Patone and colleagues as evidence refuting our hypothesis. Patone et al. focused on approximately 43 million residents of England, including just under 6 million individuals who had SARS-CoV-2 infection either before or after vaccination. The authors concluded that the risk of myocarditis was reduced by half if one experienced COVID-19 disease after receiving at least 1 dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. However, the study suffered from several fatal methodological and design flaws, as discussed by Bourdon and Pantazatos. Their recalculation of the Patone et al. data, after adjusting for underascertainment of infections and biased assumptions on post-hospitalization vaccination rates, exposed gross overestimates of the infection-related myocarditis risk for unvaccinated males under 40. This made the baseline risk appear higher, falsely inflating the claimed halving of risk in vaccinated individuals. Actual adjusted risk estimates show no reduction in myocarditis risk for those who with COVID-19 disease who received at least 1 dose mRNA vaccine dose.

Other severe cardiac outcomes further support hybrid harms. Blasco and colleagues performed a retrospective single-center cohort study involving 949 patients from March 1, 2020, to March 1, 2023, to evaluate the humoral immune response triggered by COVID-19 mRNA vaccines or SARS-CoV-2 infection. Among the participants, 656 (69%) experienced ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), a heart attack type marked by pronounced ST-segment elevation on an electrocardiogram. Vaccinated patients had significantly higher SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific IgG levels, with a median exceeding 2080 AU/mL compared to 91 AU/mL in unvaccinated individuals. This hybrid exposure (mRNA vaccination plus infection) was linked to increased rates of severe heart failure and cardiogenic shock in STEMI patients. The authors suggest this type of heart attack could be associated with a hyperimmune response stemming from the interplay between mRNA vaccines and SARS-CoV-2 infections.

In a South Korean study involving approximately 3.4 million individuals who received at least one COVID-19 mRNA injection between February 2021 and March 2022, Yun et al. analyzed heart disease risk, including acute myocarditis, acute pericarditis, acute cardiac injury, cardiac arrest, and cardiac arrhythmia. The researchers identified the date of the first diagnosis of acute heart conditions as the primary outcome and classified cardiac events occurring within 21 days post-vaccination as potential AEs linked to the vaccine. Recipients of the mRNA vaccinations who also contracted SARS-CoV-2 exhibited a nearly fourfold increased risk of heart disease compared to uninfected vaccinated individuals (adjusted HR, 3.56; 95% CI, 1.15–11.04). Younger mRNA vaccinees had a higher risk of heart disease compared to older recipients. A history of COVID-19 infection at any point was identified as a key factor elevating cardiac risk following the mRNA vaccination. This study’s findings serve as powerful substantiation of the hybrid harms phenomenon.

In a retrospective study of 886 elderly hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection at an academic medical center in Rome, Cianci and colleagues assessed clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients with heart failure (HF) compared to a matched control group of COVID-19 patients without HF. Patients were categorized as “unvaccinated” if they had never received a COVID-19 vaccine, and as “vaccinated” if they had received at least one dose. The primary outcomes were in-hospital mortality, death within 30 days of admission, and ICU admission. The presence of HF in COVID-19 patients was strongly linked to a composite outcome of death and/or ICU admission (OR, 6.46; 95% CI, 3.710–11.238; p < 0.0001). Patients with HF had significantly higher vaccination rates than those without HF: 44% of HF patients received at least one mRNA vaccine dose (p = 0.001), 18% received two doses (p = 0.002), and 22% received three doses (p = 0.0001). Vaccinated COVID-19 patients had a twofold higher likelihood of death (OR, 2.143; 95% CI, 1.094–4.199; p = 0.026) compared to unvaccinated patients. Thus, elderly hospitalized COVID-19 patients may be more likely to die following mRNA vaccination, reinforcing the potential for adverse vaccine-infection synergy.

Al-Aly and colleagues examined the risks of stroke, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary embolism in individuals with BTIs following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination with either mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2. Their findings revealed significantly elevated risks for all three conditions in those with BTIs compared to individuals without SARS-CoV-2 infection: stroke (HR = 1.76; 95% CI: 1.53–2.03), myocardial infarction (HR = 1.93; 95% CI: 1.64–2.27), and pulmonary embolism (HR = 3.94; 95% CI: 3.39–4.58). These risks increased with greater COVID-19 severity (non-hospitalized, hospitalized, and ICU cases). This indicates that fully vaccinated individuals may face a heightened risk of these serious conditions after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Somewhat paradoxically, the authors reported that the risks were reduced in comparative analyses involving BTI versus SARS-CoV-2 infection without prior vaccination; however, this finding was misleading due to classification of individuals as “unvaccinated” if they experienced any of the three serious disease events before 14 days post-second mRNA dose. This error undermines the validity of vaccinated versus unvaccinated comparisons. Thus, the study provides only limited support for the Hybrid Harms Hypothesis. Better designed studies are needed to confirm whether prior vaccination may amplify infection-related cardiovascular harm.

Reinfection studies indicate elevated post-acute risks despite potentially milder acute outcomes. Yan et al. evaluated 74,303 hospitalized patients with Omicron, including 2,244 reinfections. Survivors of reinfection faced significantly higher risks of all-cause mortality, hospital readmission, and emergency visits than those with primary infection. Approximately two-thirds of reinfection cases had received at least two mRNA doses, suggesting that prior severe infection and previous vaccination may compound vulnerability to post-acute complications. Once again, this suggests that even mRNA vaccine recipients who develop hybrid immunity against Omicron appear to be at heightened risk of serious adverse outcomes following hospitalized re-infection.

Data from Brazil’s Epidemiological Surveillance System (SIVEP) offer further support for this hypothesis. Rodrigues et al. analyzed the SIVEP dataset (2020–2023) using Cox and frailty models, adjusting for demographics, comorbidities, and vaccination status. While vaccinated individuals experienced an 8% reduction in medium-term post-COVID mortality (3 months to 1 year), long-term mortality (>1 year) nearly doubled compared to unvaccinated individuals. The authors wrote: “In the long-term period, the adjusted analysis showed that the risk of death was 69 to 94% higher for those who were vaccinated; and for those who received one and two doses of the mRNA product, the risk of death practically doubled compared to those who were not immunized (reference category).” This study was later retracted due to methodological concerns. Nevertheless, we include it here as preliminary evidence of potential long-term mRNA vaccination-related mortality risk.

Discussion

To summarize the proposed “hybrid harms” interaction, both SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination expose the human body to spike protein. This protein trimerizes and is not readily cleared from systemic circulation or tissues months to years after systemic exposure. Spike protein retention leads to immune system failure, recurrent infections, and a variety of spike protein syndromes including myocarditis, vasculopathies, venous thromboembolism, stroke, transverse myelitis, and autoimmune syndromes. Our observations call for an immediate shift in research priorities for federal agencies to focus on spike protein syndromes. Such research should fully describe the pharmacokinetics and dynamics of mRNA, adenoviral DNA, and spike protein, with an aim to clear or neutralize this dangerous pathogenic entity.

Broader implications of the Hybrid Harms Hypothesis may be listed as follows:

- Both COVID-19 mRNA vaccinations and coronavirus infections contribute to the total toxic burden of spike protein, either additively or synergistically.

- Direct toxic effects in the context of these “hybrid harms” are focused on disrupting endothelial function and triggering inflammation, potentially contributing to complications like myocarditis or thrombosis.

- Indirect effects occur via the induction of autoimmunity or chronic inflammation, particularly in the context of Long COVID, whereby persistent spike protein and/or immune complexes may drive symptoms and pathogenesis.

- Many cardiac, vascular, hematologic, autoimmune, neurological, and reproductive problems can be triggered by either the modified mRNA inoculations or coronavirus infections, or both. This hypothesis focuses on the third possibility.

- COVID-19 mRNA-inoculated individuals with either prior or subsequent exposure to SARS-CoV-2 appear to face a greater risk of thromboembolism and other vascular pathologies compared to SARS-CoV-2-naïve mRNA vaccine recipients.

- D-dimer elevation may occur, reflecting possible clot formation or immune-driven coagulopathy. Elevated D-dimer levels are commonly observed in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and correlate with thrombotic complications and worse outcomes.

- C-reactive protein (CRP) elevations are also common in pathologies resulting from the interaction between mRNA inoculations and coronavirus infections.

- Antibody testing for anti-spike antibodies provides a scientifically valid, albeit indirect measure of the body’s overall spike protein exposure from previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or the COVID-19 mRNA vaccinations.

These corollaries help to clarify the scope, predictions, and testable outcomes of our hypothesis.

On a global scale, the vast majority of COVID-19 mRNA vaccinations occurred in 2021. By 2022, Omicron had become the dominant variant, with mild pathogenicity. Yet, even in the most extensively vaccinated populations, Omicron waves coincided with paradoxical spikes in all-cause mortality. Governments typically attributed these deaths to COVID-19, often overlooking the contribution of non-COVID deaths and the preexisting immunological milieu shaped by high vaccine coverage (80–90%). We hypothesize that Omicron infections occurred against a background of mRNA-induced persistent spike protein, inflammatory lipid nanoparticles, and residual process-derived DNA, creating a toxic synergistic environment. For example, subclinical myocarditis could be exacerbated by overlapping mRNA vaccine- and coronavirus infection-derived spike protein, triggering hyperimmune responses, myocyte injury, arrhythmias, or heart failure. Evidence demonstrates that spike protein from both vaccination and infection can persist long-term, highlighting concerns for prolonged morbidity and mortality, much of which may have been misattributed to COVID-19 in 2022–2023.

The erroneous assumption of short-term spike protein expression in early 2021 helped engender the notion of a clear separation between the COVID-19 mRNA injections and coronavirus infections. This notion underlies the commonly asked public health question: Which factor causes more morbidity and mortality in the general population, the COVID-19 mRNA vaccination or Omicron infections? The dichotomy is biologically simplistic because spike protein—the shared antigen between vaccination and infection—can persist for months or years, enabling interactions that may amplify adverse outcomes. In this paper, we offer substantial evidence showing that these interactions can increase the risk of serious cardiac, hematologic, immunologic, and neurological AEs, especially in vulnerable individuals. We conjecture that persistent spike generation creates a “window of vulnerability” lasting at least two to three years (the temporal extent of observational data to date), during which coronavirus infections may amplify the mRNA vaccine-induced harms. The cumulative antigenic load promotes chronic inflammation, immune dysregulation, and cardiovascular or autoimmune events. Process-related impurities such as double-stranded RNA may further drive myocarditis and other serious outcomes.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic years, clinical misunderstanding and misreporting often arose from overuse of the RT-PCR test (often resulting in false positives and incidental misattribution) while also ignoring the interplay between mRNA vaccination and coronavirus infection. In many instances, for example, myocarditis was attributed solely to either the infections or the injections, without recognizing that prior mRNA vaccination may “prime” the myocardium, potentiating immune-inflammatory injury during subsequent infection. If infection occurs within three years of a booster dose, the heart may already be sensitized to spike protein-related toxicity. In this scenario, a previous vaccination may potentiate the SARS-CoV-2 infection’s ability to elevate myocarditis risk—particularly in younger males—rather than the infection constituting the sole cause. Given the ubiquity of mRNA vaccination and continued circulation of Omicron variants, such interactions are likely underrecognized and warrant further investigation. Statistically speaking, such interactions may be detected via regression analyses that include an interaction term such as [infection × vaccination] in logistic/Poisson regression models. In PASC studies, mRNA vaccination may be treated as the effect modifier via stratified analyses that calculate stratum-specific odds/risk ratios to quantify the amplified effects.

This hybrid harms phenomenon may explain persistent AEs among young, healthy individuals, even after Omicron’s emergence, whose intrinsic IFR in 2022 was exceedingly low (~0.0003% for children). In contrast, post-vaccination serious AEs—including sudden cardiac death in those under 40—were elevated. This may reflect a “multi-spike phenomenon,” whereby repeated exposures via vaccination and infection lead to direct toxicity, immune dysfunction, and pathological sequelae. The synthetic mRNA inoculations may predispose low-risk individuals to both infection and serious AEs, though hospitalizations in vaccinated children during Omicron waves were typically attributed solely to COVID-19, obscuring mRNA vaccine-related predisposition. Simplistic narratives that disregard prior mRNA injections continue to drive calls for additional doses and perpetuate the “safe and effective” mythos.

Adverse outcomes may result from immune perturbations induced by repeated COVID-19 mRNA doses over time. Repeated mRNA vaccination may induce IgG4 class switching, T-cell exhaustion, and pathogenic priming via non-neutralizing antibodies. The reduction in spike-specific T-cells could diminish cellular immunity and increase the risk of BTIs. Collectively, these effects could increase the likelihood of serious clinical events if exposure occurs within a 2–3 year window post-vaccination. A plausible mechanism for prolonged spike protein production involves latent integration of mRNA vaccine-derived genetic material, including plasmid-sourced DNA and promoters such as SV40, into host genomes. Such integration could result in persistent spike expression upon cellular activation, as opposed to being solely explained by mRNA stability or transient protein retention.

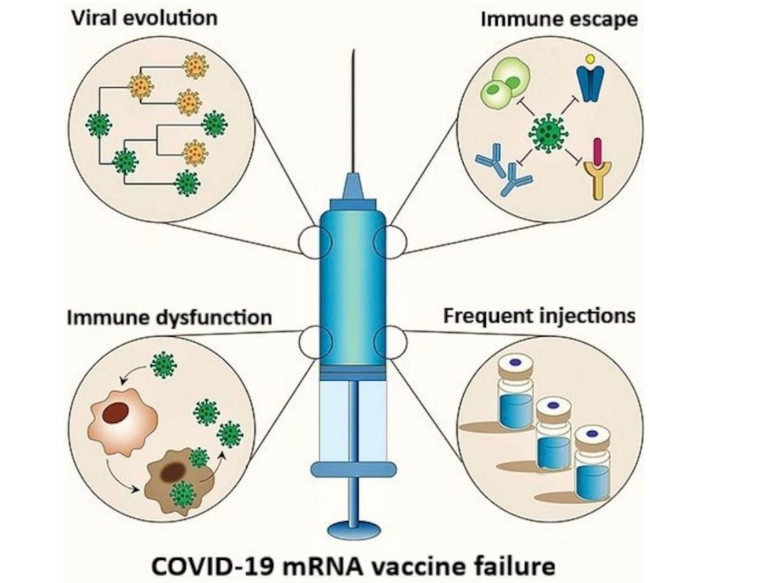

The basis for the failure of COVID-19 mRNA vaccinations has been elucidated and is illustrated in Figure 2. The SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein interacts with ACE2 receptor on host cells, creating conditions that exert significant selective pressure on the S gene, driving mutations that facilitate viral immune escape. Most of these mRNA products were developed using the S protein sequence from the original Wuhan strain, rendering them less effective against these escape variants, as the mutants can circumvent the immune responses elicited by these vaccines. This results in diminished vaccine efficacy for formulations based on the original S protein sequence. Furthermore, repeated mRNA vaccinations may alter viral dynamics, potentially promoting the emergence of immune-evasive variants, which could further reduce the effectiveness of these biologics. Additionally, frequent booster doses may contribute to excessive spike-related toxicities as well as immune dysregulation, potentially compromising antiviral and antimicrobial immunity while increasing the risk of autoimmune conditions and accelerated oncogenesis.

Direct mRNA vaccine effects—endothelial damage, pathogenic priming, and autoimmune-inflammatory processes—also merit attention. Pathogenic priming, or antibody-dependent enhancement, occurs when non-neutralizing antibodies facilitate viral entry into host cells via Fc receptors, potentially intensifying infection severity, as seen in dengue. Individuals vaccinated while infected or recently exposed may generate non-neutralizing antibodies, amplifying disease severity. Plume et al. demonstrated that IgG, IgA, and IgE antibody levels rise with disease intensity, suggesting mast cell involvement. Mast cell activation has been implicated in severe COVID-19 and PASC-related disorders, and preliminary data indicate a potential connection to mRNA vaccine–related AEs.

Numerous studies have called into question the safety profile of the mRNA injections. A comprehensive reanalysis of Pfizer trial data identified a 36% higher risk (RR, 1.36; 95% CI: 1.02–1.83) of serious AEs among mRNA vaccinees versus placebo, amounting to one serious AE per 800 doses—far exceeding historical thresholds for withdrawing a product from the market. A forensic reanalysis of Pfizer’s interim trial data, utilizing previously undisclosed narrative reports, found a nearly four-fold higher odds (OR, 3.7; 95% CI: 1.02–13.2, p=0.03) of sudden deaths and serious cardiac events among BNT162b2 recipients versus controls. Autopsy studies, clinical trial data, and post-marketing surveillance analyses revealed neurological, reproductive, musculoskeletal, thrombotic, and cardiovascular harms. Safety data from confidential Pfizer documents reported 1.6 million AEs over a six-month period. Collectively, such evidence raises fundamental concerns about safety and long-term public health impacts.

Mass vaccination during active epidemic waves carries additional epidemiological risks. High mRNA vaccine coverage in a context of ongoing viral transmission fosters selection for mRNA vaccine-resistant variants. CDC data indicate that mRNA-inoculated individuals may carry viral loads comparable to the non-vaccinated, with some studies showing higher nasopharyngeal viral loads among the mRNA-injected breakthrough cases. This could imply greater transmissibility in the context of BTIs, potentially prolonging community spread and complicating herd immunity.

The persistence of Omicron, with ongoing mutation, transmissibility, and immune evasion, further underscores the risks of repeated mRNA vaccination and the importance of learning to coexist with the coronavirus as if it were the “common cold”, without further exacerbating its pathogenicity. In principle, the removal of the mRNA products from global distribution would contribute substantially toward meeting this objective.

The epidemiological implications of this integrated perspective are substantial. Temporal causal reasoning, the tendency to link an outcome to the most recent or obvious preceding event, is a standard approach in both clinical practice and epidemiological studies. Against a backdrop of extensive COVID-19 vaccinations (70-80% coverage for most populations in developed countries), the coronavirus infection appears temporally proximal to the serious AE, making it the default suspect. The Hybrid Harms Hypothesis emphasizes that post-vaccination AEs may be erroneously classified as COVID-19 outcomes due to these temporal biases. As an example, severe myocarditis occurring after the mRNA vaccination is often attributed to SARS-CoV-2 infection when the infection occurs closer to the detection of myocarditis. Several coauthors of the current paper have recently laid out an in-depth explanation as to why this assertion is incorrect. In that narrative review, however, the authors did not consider a question that forms the core premise of our present inquiry: How many of those infection-associated cardiac events were either preceded or followed by exposure to COVID-19 mRNA vaccinations (within a biologically relevant window in terms of interactive potential), which could have predisposed the infected individuals to more disease outcomes? Moreover, how often does temporal bias inflate estimates of infection-related myocarditis and obscure mRNA vaccination-related cardiac harms?

The Hybrid Harms Hypothesis offers a new lens on many studies that overlooked potential interactions between the COVID-19 mRNA injections and SARS-CoV-2 infections. For instance, in a large-scale U.S. analysis involving almost 5 million adults, those who contracted SARS-CoV-2 within 21 days after vaccination faced significantly elevated stroke risks compared to vaccinated individuals without recent infection. Specifically, the odds ratio for ischemic stroke reached 8.00 (95% CI: 4.18–15.31), while hemorrhagic stroke showed an odds ratio of 5.23 (95% CI: 1.11–24.64). This elevated risk was particularly pronounced among recipients of mRNA-1273; however, compared to the mRNA product, BNT162b2, the adenoviral vector product (Ad26.COV2.S) carried a greater likelihood of early ischemic stroke in this cohort. Overall, a SARS-CoV-2 infection occurring shortly before or after mRNA vaccination was linked to a marked rise in early-onset ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. The study authors emphasized that concurrent COVID-19 infection exhibited the most robust correlation with these acute stroke events following the initial vaccine dose. That said, the analysis did not fully account for all stroke risk factors, such as underlying health conditions. This study illustrates how, despite the widely claimed rewards of the hybrid immunity approach, the potential risks may greatly outweigh any theoretical benefits.

We postulate that a significant proportion of PASC cases reported since 2021 may be attributable to mRNA vaccine-related immunological effects in conjunction with those effects associated with the coronavirus infection, rather than to the natural infection alone. From a critical research perspective, many studies may not adequately take into account the influence of COVID-19 mRNA vaccination on PASC outcomes, as well as the pathological redundancy between the injections and infections. Some PASC conditions (e.g., cardiovascular, hematological, and neurological) clearly overlap with known AEs linked with the COVID-19 mRNA products, such as myocarditis, stroke, or thromboembolism. The scientific community does not restrict PASC to unvaccinated individuals, mainly because COVID-19 vaccinated individuals with BTIs or reinfections can and do develop PASC. Due to the identical signs and symptoms, however, some cases counted as PASC may actually be mRNA vaccine injuries, either short term or long term. If these vaccine-related AEs (e.g., myocarditis, stroke, or thromboembolism) are misclassified as PASC, this would artificially inflate the reported PASC incidence in the vaccinated group. This, in turn, would mean that many mRNA vaccine injuries could be solely and thus erroneously attributed to the adverse effects of the coronavirus infection rather than to the mRNA vaccination.

This misclassification is further complicated by the case-counting window bias, a pervasive problem in studies comparing COVID-19 vaccinated to unvaccinated groups, invariably biasing upward the safety and effectiveness of the mRNA vaccinations. The unvaccinated are being grouped together with previously mRNA-injected individuals people who either (a) have not yet reached “immunologic maturity” on the first two injections (i.e., not up to 14-28 days after the second injection), (b) only partially vaccinated, or (c) or were vaccinated too long ago to be considered “up-to-date” and thus counted as having mRNA vaccine-induced immunity. Any PASC-like AEs that arise in these mRNA-injected individuals are thus counted as occurring among the “unvaccinated”. Due to this additional layer of misclassification, the mRNA vaccine-related AEs are misclassified as PASC occurring among the unvaccinated. This fraudulent practice has profoundly distorted many risk-benefit analyses of COVID-19 mRNA vaccinations, resulting in gross overestimates (largely inverted) of the mRNA products’ ability to reduce cardiovascular, hematological, neuropsychiatric, and autoimmune PASC outcomes. Most egregiously, such misclassification supports the false claim that the COVID-19 vaccinations actually reduce PASC.

The common practice of miscategorizing the unvaccinated, due to the case-counting window bias, means that those who never received the modified mRNA injections—that is, the true “unvaccinated”—are unfairly characterized in the public eye. This is because the practice results in misattributing adverse health outcomes to a group that may have lower risks of many PASC outcomes that overlap with mRNA vaccine-induced AEs. Whether or not this is being done deliberately, the miscategorizations serve to (a) reinforce the “safe and effective” narrative, thereby ensuring more pharmaceutical industry funding of mRNA vaccination and PASC research, and (b) motivate the policymakers, commentators, and the general public to continue to embrace the vaccinations.

Regulatory perspectives emphasize the need for more robust controls in the research setting. The FDA now recommends placebo-controlled trials to fully document AEs. FDA guidance also states that placebo controls can distinguish AEs and outcomes specifically caused by a drug or vaccine from those due to underlying disease or “background noise”. In a recent commentary, Taccetta discusses how this concept assumes that no persistent, potentially confounding vaccine or drug components would be present in participants at the start of the study. Indeed, the persistent noise of mRNA vaccine-associated spike protein and modified mRNA in some individuals may exceed typical background noise, potentially confounding the assessment of safety and efficacy. Comprehensive pharmacokinetic studies, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, are necessary to establish true baseline conditions. A minimum three-year “washout” period is recommended to account for persistent synthetic mRNA and spike protein before baseline measurements. Without such precautions, trial outcomes may misattribute risk between pre-existing mRNA vaccine exposure and investigational interventions.

Disclosure statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding Statement: None.

Acknowledgements: We thank vaccinologist Geert vanden Bossche for sharing his immunological perspectives. Thanks also to Dutch elderly care physician and medical ethicist Elizabeth Bennink, MD, MA, for insightful feedback on the manuscript. Additional thanks to Scott Sutton of the COVID Index team for suggestions on graphics.

ORCID ID:

- M. Nathaniel Mead- 0009-0003-3574-4675

- Jessica Rose- 0000-0002-9091-4425

- Stephanie Seneff- 0000-0001-8191-1049

- Claire Rogers- 0000-0002-1056-637X

- Nicolas Hulscher- 0009-0008-0677-7386

- Kirstin Cosgrove- 0009-0007-4964-6215

- Breanne Craven- 0009-0006-6955-6770

- Paul Marik- 0000-0001-5024-3949

- Peter McCullough- 0000-0002-0997-6355

References

1. Hu B, Huang S, Yin L. The cytokine storm and COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):250-256. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26232

2. Ejaz H, Alsrhani A, Zafar A, Javed H, Junaid K, Abdalla AE, Abosalif KOA, et al. COVID-19 and comorbidities: Deleterious impact on infected patients. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(12):1833-1839. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.07.014

3. Ge E, Li Y, Wu S, Candido E, Wei X. Association of pre-existing comorbidities with mortality and disease severity among 167,500 individuals with COVID-19 in Canada: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258154

4. Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Zuliani G, Rigatelli A, Mazza A, Roncon L. Arterial hypertension and risk of death in patients with COVID-19 infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81(1):e84-e86. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.059

5. Cariou B, Hadjadj S, Wargny M, Pichelin M, Al-Salameh A, Allix I, Amadou C, et al.; CORONADO investigators. Phenotypic characteristics and prognosis of inpatients with COVID-19 and diabetes: the CORONADO study. Diabetologia. 2020;63(8): 1500-1515. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05180-x

6. Lazcano U, Cuadrado-Godia E, Grau M, Subirana I, Martínez-Carbonell E, Boher-Massaguer M, Rodríguez-Campello A, et al. Increased COVID-19 Mortality in People With Previous Cerebrovascular Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Stroke. 2022;53(4):1276-1284. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA. 121.036257

7. Phelps M, Christensen DM, Gerds T, Fosbøl E, Torp-Pedersen C, Schou M, Køber L, et al. Cardiovascular comorbidities as predictors for severe COVID-19 infection or death. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2021;7(2):172-180. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa081

8. Suleyman G, Fadel RA, Malette KM, Hammond C, Abdulla H, Entz A, Demertzis Z, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Morbidity Associated With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in a Series of Patients in Metropolitan Detroit. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6) :e2012270. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12270

9. Ioannou GN, Locke E, Green P, Berry K, O’Hare AM, Shah JA, Crothers K, et al. Risk Factors for Hospitalization, Mechanical Ventilation, or Death Among 10 131 US Veterans With SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2022310. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22310

10. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Perez JL , et al.; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJ Moa2034577

11. El Sahly HM, Baden LR, Essink B, Doblecki-Lewis S, Martin JM, Anderson EJ, Campbell TB, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine at Completion of Blinded Phase. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1774-1785. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2113017

12. Vaccine Research & Development. How can COVID-19 vaccine development be done quickly and safely? Retrieved on October 16, 2025, from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/vaccines/timeline

13. New York State Department of Health. The science behind vaccine research and testing. Retrieved on October 16, 2025, from https://www.health.ny.gov/prevention/immunization/vaccine_safety/science.htm

14. Cosentino M, Marino F. Understanding the Pharmacology of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines: Playing Dice with the Spike? Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(18):10881. doi: 10.3390/ijms231810881

15. Chaudhary JK, Yadav R, Chaudhary PK, Maurya A, Kant N, Rugaie OA, Haokip HR, et al. Insights into COVID-19 Vaccine Development Based on Immunogenic Structural Proteins of SARS-CoV-2, Host Immune Responses, and Herd Immunity. Cells. 2021;10(11):2949. doi: 10.3390/ cells10112949

16. Painter MM, Mathew D, Goel RR, Apostolidis SA, Pattekar A, Kuthuru O, Baxter AE , et al. Rapid induction of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells is associated with coordinated humoral and cellular immunity to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Immunity. 2021;54(9):2133-2142.e3. doi: 10.1016/ j.immuni.2021.08.001

17. Oldfield PR, Gutschi M, McCullough PA, Speicher DJ. BioNTech’s COVID-19 modRNA Vaccines: Dangerous genetic mechanism of action released before sufficient preclinical testing. Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons. 2024;29(4):118-126

18. Elsayed BMS, Altarawneh L, Farooqui HH, Khan MN, Babu GR, Doi SAR, Chivese T. Association Between Pre-Existing Conditions and COVID-19 Hospitalization, Intensive Care Services, and Mortality: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of an International Global Health Data Repository. Pathogens. 2025 Sep 11;14(9):917. doi: 10.3390/ pathogens14090917

19. World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 dashboard. COVID-19 cases, World. Accessed on 2 October 2025. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=o

20. Rustagi V, Gupta SRR, Talwar C, Singh A, Xiao ZZ, Jamwal R, Bala K, et al. SARS-CoV-2 pathophysiology and post-vaccination severity: a systematic review. Immunol Res. 2024;73(1):17. doi: 10.1007/s12026-024-09553-x

21. Swiss Re Group. Covid-19 may lead to longest period of peacetime excess mortality, says new Swiss Re report. Swiss Re Institute, Zurich. 16 Sep 2024. https://www.swissre.com/press-release/Covid-19-may-lead-to-longest-period-of-peacetime-excess-mortality-says-new-Swiss-Re-report/eadc133c-01bd-49e8-9f3a-a3025a3380e6

22. World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 dashboard. COVID-19 deaths, World. Accessed on 2 October 2025. URL: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths?n=o

23. Binnicker MJ. Challenges and Controversies to Testing for COVID-19. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58 (11):e01695-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01695-20.

24. Pujadas E, Chaudhry F, McBride R, Richter F, Zhao S, Wajnberg A, Nadkarni G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load predicts COVID-19 mortality. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(9):e70. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30354-4.

25. Mallett S, Allen AJ, Graziadio S, Taylor SA, Sakai NS, Green K, Suklan J, et al. At what times during infection is SARS-CoV-2 detectable and no longer detectable using RT-PCR-based tests? A systematic review of individual participant data. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):346. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01810-8

26. Jefferson T, Spencer EA, Brassey J, Heneghan C. Viral Cultures for Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infectivity Assessment: A Systematic Review. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):e3884-e3899. doi: 10.1093 /cid/ciaa1764.

27. Basoulis D, Logioti K, Papaodyssea I, Chatzopoulos M, Alexopoulou P, Mavroudis P, Rapti V, et al. Deaths “due to” COVID-19 and deaths “with” COVID-19 during the Omicron variant surge, among hospitalized patients in seven tertiary-care hospitals, Athens, Greece. Sci Rep. 20 25;15(1):13728. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-98834-y

28. Ward T, Fyles M, Glaser A, Paton RS, Ferguson W, Overton CE. The real-time infection hospitalisation and fatality risk across the COVID-19 pandemic in England. Nat Commun. 2024; 15(1):4633. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-47199-3.

29. Mohapatra RK, Sarangi AK, Kandi V, Azam M, Tiwari R, Dhama K. Omicron (B.1.1.529 variant of SARS-CoV-2); an emerging threat: Current global scenario. J Med Virol. 2022 May;94(5):1780-1783. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27561

30. Karyakarte RP, Das R, Dudhate S, Agarasen J, Pillai P, Chandankhede PM, Labhshetwar RS, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases infected with Omicron subvariants and the XBB recombinant variant. Cureus. 2023;15(2):e35261. doi: 10.7759/ cureus.35261

31. Meng B, Abdullahi A, Ferreira IATM, Goonawardane N, Saito A, Kimura I, Yamasoba D, et al. Altered TMPRSS2 usage by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron impacts infectivity and fusogenicity. Nature. 2022;603(7902 ):706-714. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04474-x.

32. Omicron Joung SY, Ebinger JE, Sun N, Liu Y, Wu M, Tang AB, Prostko JC, et al. Awareness of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant infection among adults with recent COVID-19 seropositivity. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8):e2227241. doi: 10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2022.27241

33. Christie B. COVID-19: Early studies give hope omicron is milder than other variants. BMJ 2021;375:n3144. PMID: 34949600

34. Zhao H, Lu L, Peng Z, Chen LL, Meng X, Zhang C, Ip JD, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant shows less efficient replication and fusion activity when compared with Delta variant in TMPRSS2-expressed cells. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11(1) :277-283. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.2023329.

35. Tureček P, Kleisner K. Symptomatic mimicry between SARS-CoV-2 and the common cold complex. Biosemiotics. 2022;15(1):61–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12304-021-09472-6

36. Lorenzo-Redondo R, Ozer EA, Hultquist JF. COVID-19: is omicron less lethal than delta? BMJ. 2022;378:o1806. PMID: 35918084.

37. Pather S, Madhi SA, Cowling BJ, Moss P, Kamil JP, Ciesek S, Muik A, Türeci Ö. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants: burden of disease, impact on vaccine effectiveness and need for variant-adapted vaccines. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1130539. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1130539

38. Excess Mortality Project. Excess mortality calculations for different countries. Phinance Technologies. Accessed 7/18/2025. URL: https://phinancetechnologies.com/HumanityProjects/Projects.htm

39. Kuhbandner C, Reitzner M. Estimation of Excess Mortality in Germany During 2020-2022. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e39371. doi: 10.7759/cureus.39371

40. Aarstad J, Kvitastein OA. Is there a link between the 2021 COVID-19 vaccination uptake in Europe and 2022 excess all-cause mortality? Asian Pac. J. Health Sci. 2023;10(1):25-31. https://www.apjhs.com/index.php/apjhs/article/view/3017/1610

41. Economidou EC, Soteriades ES. Excess mortality in Cyprus during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. Vaccine. 2024;42(15):3375-3376. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.11.028

42. Raknes G, Fagerås SJ, Sveen KA, Júlíusson PB, Strøm MS. Excess non-COVID-19 mortality in Norway 2020-2022. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1) :244. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-17515-5

43. Mostert S, Hoogland M, Huibers M, Kaspers G. Excess mortality across countries in the Western World since the COVID-19 pandemic: ‘Our World in Data’ estimates of January 2020 to December 2022. BMJ Public Health 2024;2:e000282. doi:10. 1136/bmjph-2023-000282. https://bmjpublichealth.bmj.com/content/2/1/e000282

44. Cao X, Li Y, Zi Y, Zhu Y. The shift of percent excess mortality from zero-COVID policy to living-with-COVID policy in Singapore, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and Hong Kong SAR. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1085451. doi: 10.3389/fpu bh.2023.1085451

45. Scherb H. and K. Hayashi. Annual All-Cause Mortality Rate in Germany and Japan (2005 to 2022) With Focus on The COVID-19 Pandemic: Hypotheses And Trend Analyses. Med Clin Sci 5(2): 1-7. https://journals.sciencexcel.com/index.php/mcs/article/view/411/413

46. De Padua Durante AC, Lacaza R, Lapitan P, Kochhar N, Tan ES, Thomas M. Mixed effects modelling of excess mortality and COVID-19 lockdowns in Thailand. Sci Rep. 2024 Apr 8;14(1):8240. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-58358-3.

47. Fenton NE, Neil M, McLachlan S. Paradoxes in the reporting of COVID19 vaccine effectiveness: Why current studies (for or against vaccination) cannot be trusted and what we can do about it. ResearchGate. 2021. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.32655.30886

48. Lataster R. How the adverse effect counting window affected vaccine safety calculations in randomised trials of COVID-19 vaccines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2024 Apr;30(3):453-458. doi: 10.1111/jep.13962.