Long-COVID Clinical Development and Outcome Assessment

Analysis of the clinical development landscape targeting long-COVID and evolution of clinical outcome assessment methods – An industry perspective

Pandey, Ramesh Chandra1; Kumar, Saurabh2*

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 March 2025

CITATION: PANDEY, Ramesh Chandra; KUMAR, Saurabh. Analysis of the clinical development landscape targeting long-COVID and evolution of clinical outcome assessment methods – An industry perspective. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 3, mar. 2025. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6320>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i3.6320

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Long COVID is the term used for health complications seen in patients recovered from acute coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Since the pandemic, there have been more than 700 million cases and over 7 million deaths reported worldwide (https://data.who.int/table/WHO/). Experts believe that these numbers are an underestimate due to lower and inaccurate reporting from LMIC (low- and middle-income countries). Particularly, the incidence surged in three distinct waves during the years between 2020 and 2022, primarily driven by different SARS-CoV-2 variants prevalent at that time. The opportunities for long-COVID research are vast, with a growing number of clinical trials initiated by the pharmaceutical industry. This paper aims to reassess the landscape as it pertains to long-COVID and to evaluate the clinical outcome assessment methods utilized in the studies cited.

Keywords

- Long COVID

- Clinical trials

- Outcome assessment

- Pharmaceutical industry

Introduction

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) is an upper and lower respiratory tract infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 which caused a pandemic with more than 700 million cases and over 7 million deaths reported worldwide (https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19). Experts believe that these numbers are an underestimate due to lower and inaccurate reporting from LMIC (low- and middle-income countries). Particularly, the incidence surged in three distinct waves during the period of three years between 2020 and 2022, primarily driven by different SARS-CoV-2 variants prevalent at that time. The opportunities of longer follow-up post-pandemic, in patients recovered from acute COVID-19 disease resulted in identification of distinct health concern — post-COVID-19 syndrome or long-COVID. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE; UK) defines the post-COVID-19 syndrome (or post-COVID syndrome) as a set of persistent physical, cognitive, and/or psychological symptoms that continue for more than 12 weeks after illness and which are not explained by an alternative diagnosis (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188). Alternate definitions further sub-classify Post-COVID Syndrome into Long post-COVID symptoms and Persistent post-COVID symptoms, depending on the duration of persistence and has been reviewed elsewhere earlier. However, in the literature Long-COVID has been often used interchangeably with post-COVID syndrome.

Previously, Umesh et al. (2022) reviewed multifunctional pathophysiology such as pulmonary, neuropsychological, and cardiovascular complications, as well as dysfunctional gastrointestinal, endocrine, and metabolic health, which were responsible for health concerns in long-COVID patients. However, most of the industry-sponsored studies were focused on pulmonary symptoms. Although the epidemiological trends suggested a rise in cardiovascular complications, they were not addressed by most ongoing clinical studies at that time. Being a chronic condition, a longer follow-up period post-pandemic provides an opportunity to revisit the initial cardiovascular understanding. It is essential to re-assess the landscape after 3-4 years of the pandemic waves with respect to an emerging understanding of long-COVID as a health concern, the pharma industry’s innovation and investments to address them, and new ways to evaluate health outcomes from a real-world perspective. In this study, we highlight the trends in the landscape of industry-sponsored clinical activities (observational and interventional studies) addressing long-COVID over the period, based on the data from a clinical trial registry. We also explore deeper into the study designs and review the methods to assess the clinical outcomes that have evolved with greater emphasis on patient-reported outcomes. In addition, we also discuss the recent trends in understanding of long-COVID with respect to additional understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms and how the lack of specific diagnosis biomarkers for long-COVID is a barrier to further advancement in this field.

Methods

This analysis was conducted in three steps:

-

Access a clinical trial registry to extract information about industry-sponsored studies as a dataset,

-

Sequential shortlisting and curation of the data set, and

-

Detailed analysis of the clinical studies that qualified the inclusion criteria, including type of assets, phase of development etc.

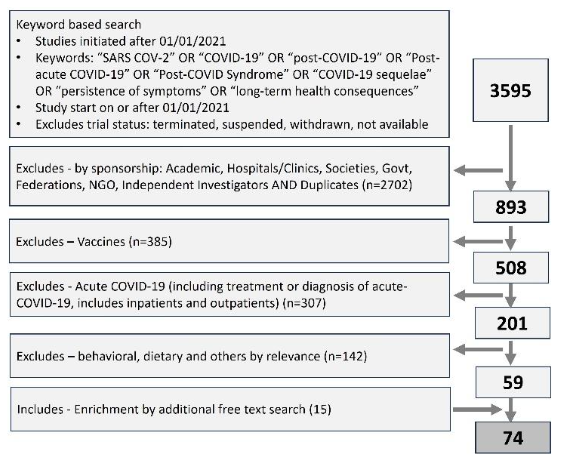

Clinical trial universe was assessed from the clinical trial registry maintained by National Library of Medicine (www.clinicaltrials.gov). The search string consisted of words and synonyms such as SARS COV-2, COVID-19, post-COVID-19, Post-acute COVID-19, Post-COVID Syndrome, COVID-19 sequelae, long COVID, persistence of symptoms and long-term health consequences (Figure 1). Timeline filter applied for the data extraction was the trial start date of 01/01/2021 or later. The data was downloaded from the registry on 30th Nov 2024 and 2nd Jan 2025 and merged. Only active clinical trials were considered for the analysis, excluding studies that were terminated, suspended, withdrawn or where the exact status was not available.

As the next step, the data universe was subjected to step-by-step shortlisting to include industry-sponsored clinical studies focusing on post-COVID syndrome or long COVID (Figure 1). The shortlisting criteria included exclusions like academic sponsorship, vaccines, studies focusing on acute-COVID-19, behavioral, physiotherapy or dietary interventions, and studies where the relevance or intent of the study in relation to long-COVID could not be established by the study description. The dataset was manually curated to address the inconsistency of the classification, such as industry sponsorship, trial focus, terminologies used in the studies etc.

Finally, the data available in the included trials were analyzed in detail to review the development stage and classify innovative approaches like medical devices, algorithms, biologics, etc., based on the information retrieved from the clinical trial registry.

Figure 1: Prisma diagram showing the extracting and step-by-step shorting of industry sponsored clinical studies focusing on long-COVID. Clinical trial data was extracted from clinicaltrials.gov, a trial registry maintained by national library of medicine, USA.

Results

A. INDUSTRY-SPONSORED CLINICAL STUDY LANDSCAPE ADDRESSING LONG-COVID

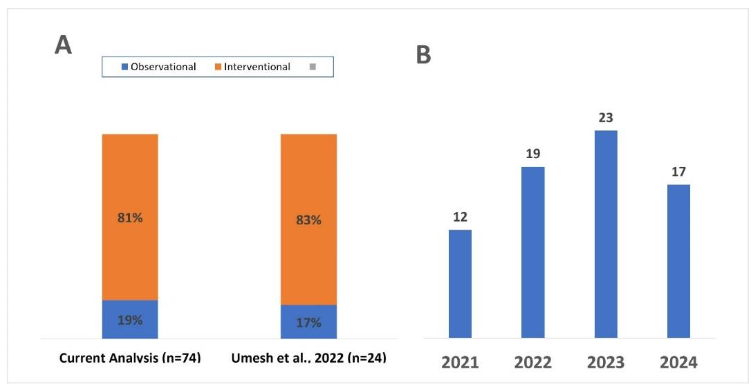

We analyzed 74 new initiated clinical studies, from the registry with start date on or after 01 Jan 2021. Among the 74 new clinical studies sponsored or initiated by Industry that were initiated after 2021, 81% were interventional and 19% were observational (Figure 2-A). Year-on-year (YOY) landscape demonstrates that long-COVID remains a focus for pharma industry (Figure 2-B). The landscape shows that an average of ~20 new industry-sponsored clinical studies were initiated annually over the last three years (17-25) and three studies are pre-planned for 2025 (Figure 2).

The type of interventions under assessment include small molecule drugs, biologic assets such as monoclonal antibodies or cell/gene therapies, MedTech interventions such as neurostimulation devices or digital therapeutics etc. (Table 1). Interestingly, there are a few innovative approaches involving leveraging of data/algorithm or machine learning to aid in the diagnosis or prognosis of the long-COVID.

You said:

ChatGPT said:

References

1. Park MB, Ranabhat CL. COVID-19 trends, public restrictions policies and vaccination status by economic ranking of countries: a longitudinal study from 110 countries. Arch Public Health 2022; 80(1):197. DOI: 10.1186/s13690-022-00936-w.

2. Thakur I, Chatterjee A, Ghosh AK, et al. A comparative study between first three waves of COVID-19 pandemic with respect to risk factors, initial clinic-demographic profile, severity and outcome. J Family Med Prim Care 2024;13(6):2455-2461. DOI: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1884_23.

3. Bali Swain R, Lin X, Wallentin FY. COVID-19 pandemic waves: Identification and interpretation of global data. Heliyon 2024;10(3):e25090. DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25090.

4. Umesh A, Pranay K, Pandey RC, Gupta MK. Evidence mapping and review of long-COVID and its underlying pathophysiological mechanism. Infection 2022;50(5):1053-1066. DOI: 10.1007/s15010-022-01835-6.

5. Sivan M, Preston N, Parkin A, et al. The modified COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRSm) patient-reported outcome measure for Long Covid or Post-COVID-19 syndrome. J Med Virol 2022;94(9):4253-4264. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.27878.

6. Chharia A, Jeevan G, Jha RA, Liu M, Berman JM, Glorioso C. Accuracy of US CDC COVID-19 forecasting models. Front Public Health 2024;12: 1359368. DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1359368.

7. USFDA. FDA Approves First Drug to Treat Group of Rare Blood Disorders in Nearly 14 Years. FDA News Release 2020

(https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-drug-treat-group-rare-blood-disorders-nearly-14-years).

8. Lamb YN, Syed YY, Dhillon S. Immune Globulin Subcutaneous (Human) 20% (Hizentra((R))): A Review in Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy. CNS Drugs 2019;33(8):831-838. DOI: 10.1007/s40263-019-00655-x.

9. Bian H, Chen L, Zheng ZH, et al. Meplazumab in hospitalized adults with severe COVID-19 (DEFLECT): a multicenter, seamless phase 2/3, randomized, third-party double-blind clinical trial. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023;8(1):46. DOI: 10.1038/s41392-023-01323-9.

10. Kanegane H, Imai K, Yamada M, et al. Efficacy and safety of IgPro20, a subcutaneous immunoglobulin, in Japanese patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases. J Clin Immunol 2014; 34(2):204-11. DOI: 10.1007/s10875-013-9985-z.

11. Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature 2021;594(7862):259-264. DOI: 10.103 8/s41586-021-03553-9.

12. Chen C, Haupert SR, Zimmermann L, Shi X, Fritsche LG, Mukherjee B. Global Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J Infect Dis 2022;226(9):1593-1607. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/jiac136.

13. Franco JVA, Garegnani LI, Metzendorf MI, Heldt K, Mumm R, Scheidt-Nave C. Post-covid-19 conditions in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of health outcomes in controlled studies. BMJ Med 2024;3(1):e000723. DOI: 10.1136/bmjmed-2023-000723.

14. Huang L, Li X, Gu X, et al. Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2022;10(9):863-876. DOI: 10.1016/S22 13-2600(22)00126-6.

15. Kaur H, Chauhan A, Mascarenhas M. Does SARS Cov-2 infection affect the IVF outcome – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2024;292:147-157. DOI: 10.1 016/j.ejogrb.2023.11.027.

16. Tanriverdi O, Alkan A, Karaoglu T, Kitapli S, Yildiz A. COVID-19 and Carcinogenesis: Exploring the Hidden Links. Cureus 2024;16(8):e68303. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.68303.

17. Lai YJ, Liu SH, Manachevakul S, Lee TA, Kuo CT, Bello D. Biomarkers in long COVID-19: A systematic review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023;10: 1085988. DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1085988.

18. Espin E, Yang C, Shannon CP, Assadian S, He D, Tebbutt SJ. Cellular and molecular biomarkers of long COVID: a scoping review. EBioMedicine 2023;91:104552. DOI: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104552.

19. Thomas C, Faghy MA, Chidley C, Phillips BE, Bewick T, Ashton RE. Blood Biomarkers of Long COVID: A Systematic Review. Mol Diagn Ther 2024; 28(5):537-574. DOI: 10.1007/s40291-024-00731-z.

20. Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 1989;46(10):1121-3. DOI: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022.

21. Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999;54(7):581-6. DOI: 10.1136/thx.54.7.581.

22. Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res 1993;37(2):147-53. DOI: 10.1016/0022-3999(93) 90081-p.

23. Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord 2009;114(1-3):163-73. DOI: 10.1016 /j.jad.2008.06.026.

24. Yar T, Salem AM, Rafique N, et al. Composite Autonomic Symptom Score-31 for the diagnosis of cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in long-term coronavirus disease 2019. J Family Community Med 2024;31(3):214-221. DOI: 10.4103/jfcm.jfcm_20_24.

25. Sletten DM, Suarez GA, Low PA, Mandrekar J, Singer W. COMPASS 31: a refined and abbreviated Composite Autonomic Symptom Score. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87(12):1196-201. DOI: 10.1016/j.mayoc p.2012.10.013.

26. Michielsen HJ, De Vries J, Van Heck GL. Psychometric qualities of a brief self-rated fatigue measure: The Fatigue Assessment Scale. J Psychosom Res 2003;54(4):345-52. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3999 (02)00392-6.

27. de Jong CMM, Le YNJ, Boon G, Barco S, Klok FA, Siegerink B. Eight lessons from 2 years of use of the Post-COVID-19 Functional Status scale. Eur Respir J 2023;61(5). DOI: 10.1183/13993003.0 0416-2023.

28. Mamyrbaev A, Turmukhambetova A, Bermagambetova S, et al. Assessing psychometric challenges and fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Life 2023;16(10):1527-1533. DOI: 10.25122/jml-2023-0244.