Metabolic Impact of Subclinical Hypothyroidism in Liver Disease

Metabolic, Inflammatory and Oxidative Alterations in Patients with Steatotic Liver Disease: Role of Subclinical Hypothyroidism

Olena V. Kolesnikova ¹, Anastasiia O. Radchenko ¹, Olga Ye. Zaprovalna ¹

¹ L.T. Malaya Therapy National Institute of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine, Kharkiv, Ukraine

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 July 2025

CITATION Kolesnikova, OV., Radchenko, AO., et al., 2025. Metabolic, Inflammatory and Oxidative Alterations in Patients with Steatotic Liver Disease: Role of Subclinical Hypothyroidism. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(7). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6671

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6671

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Background: Subclinical hypothyroidism has emerged as a potential contributor to the metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, particularly in individuals with coexisting hypertension.

Aims: To evaluate metabolic profiles, inflammatory markers, and oxidative stress parameters in hypertensive patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, depending on the presence of concomitant subclinical hypothyroidism.

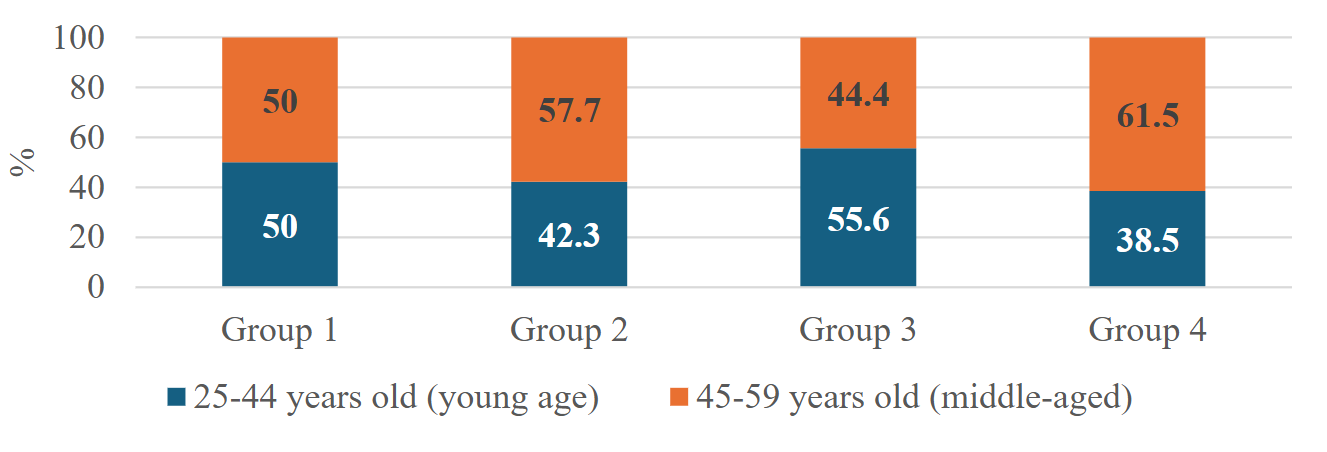

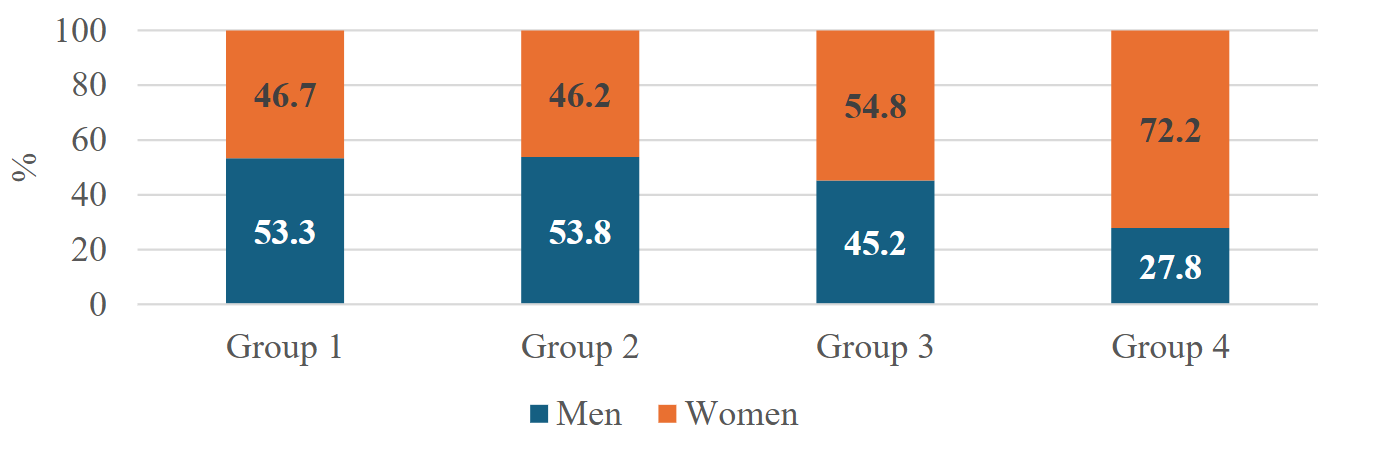

Methods: A total of 126 patients examined from 2019 to 2022 were divided into four groups: Group 1 – controls (n = 30); Group 2 – hypertensive patients with steatotic liver disease (n = 26); Group 3 – patients with hypertension and subclinical hypothyroidism (n = 18); and Group 4 – patients with all three conditions (n = 52). In Groups 3 and 4, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels ranged from 4 to 10 mU/L. Anthropometric parameters, biochemical profile, inflammatory (C-reactive protein, CRP, tumor necrosis factor α, TNF-α), and oxidative stress markers (total hydroperoxide content, THP, total antioxidant activity, TAA) were assessed.

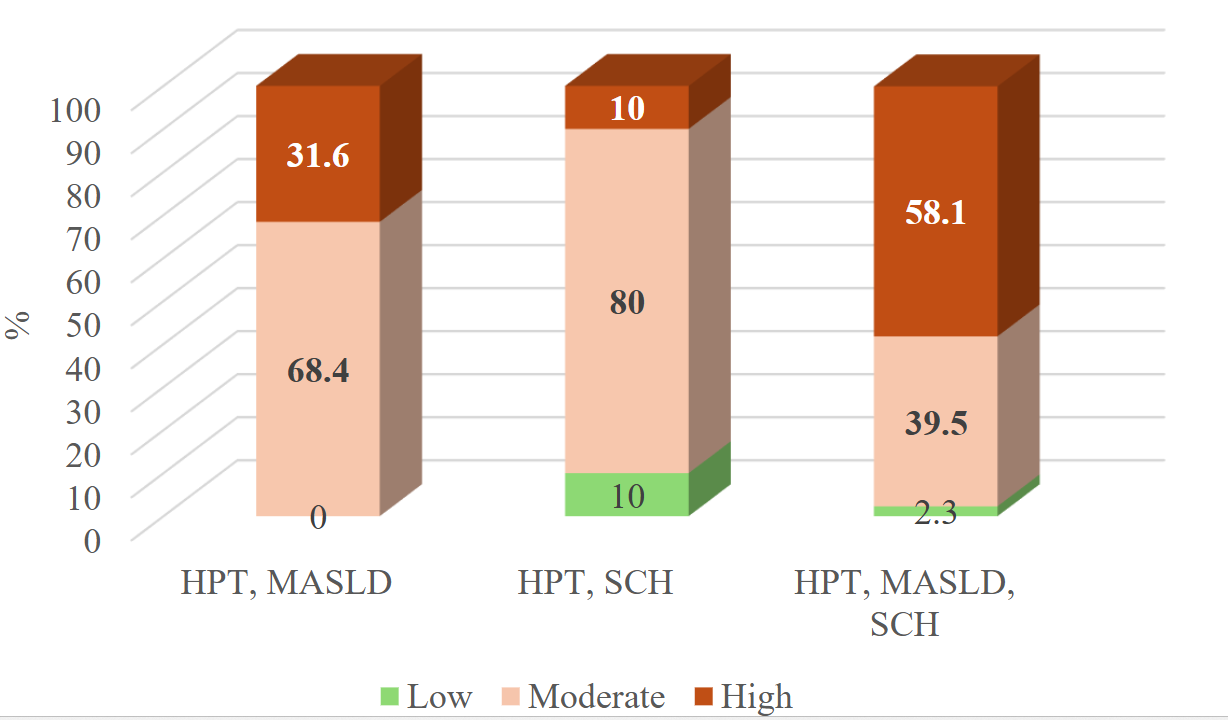

Results: The presence of subclinical hypothyroidism (in either Group 3 or 4) was associated with significantly higher hip circumference (p < 0.05), lower waist-to-hip ratio (p < 0.001), elevated levels of glycated hemoglobin (p < 0.05), CRP (p < 0.05), and TNF-α (p < 0.001). Significantly higher levels of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) (p = 0.005) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (p = 0.028), total cholesterol (p = 0.021), aspartate aminotransferase (p = 0.01), alkaline phosphatase (p = 0.034), THP (p = 0.014), and lower levels of HDL-C (p = 0.027) and glomerular filtration rate (p = 0.048) were observed in Group 4 compared to Group 2. In Group 4, TSH levels were positively associated with glucose (p = 0.008), TNF-α (p < 0.001), and inversely associated with HDL-C (p < 0.001), glomerular filtration rate (p < 0.001), and TAA (p = 0.012). A significantly higher proportion had a high cardiovascular risk according to SCORE2 in Group 4 compared to Group 2 (p = 0.023).

Conclusion: Subclinical hypothyroidism significantly contributes to the cardiometabolic burden in hypertensive patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Even among patients with mild subclinical hypothyroidism, higher systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, impaired glucose control, and lipid dysregulation are observed.

Keywords

Subclinical hypothyroidism, metabolic dysfunction, steatotic liver disease, hypertension, oxidative stress

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is one of the most common liver diseases in the world. Its prevalence is steadily increasing, which is primarily due to the increasing incidence of obesity and metabolic syndrome, caused by a sedentary lifestyle, impaired diet, abuse of processed foods and increased working hours. This problem is especially relevant in developed countries, where these factors have become commonplace for the majority of the population. Chronic sleep disturbance, irregular meals, frequent snacking, and alcohol abuse also contribute to the deterioration of metabolic health.

Hypothyroidism, including its subclinical form (SCH), is considered an unconventional but potentially significant risk factor for the development of MASLD. SCH is associated with a number of metabolic changes, including insulin resistance (IR), dyslipidemia (DL), and weight gain. In patients with MASLD, the presence of SCH may contribute to both the acceleration of the progression of metabolic disorders and the increase in the severity of existing disorders.

Unhealthy lifestyles, particularly in populations living in naturally iodine-deficient areas, contribute to the prevalence of hypothyroidism, especially in the absence of effective salt iodization programs. According to the NHANES study in the United States, hypothyroidism is detected in 4.6% of the adult population, of which 0.3% have a clinically manifest form, and the rest have SCH. In European countries, the prevalence of manifest hypothyroidism is on average 0.2–2%, while SCH occurs in 4–10% of adults. In countries with a developed health care system, SCH is more often detected, which is associated with wider access to laboratory diagnostics.

Ukraine traditionally belongs to the regions with mild to moderate iodine deficiency. The most endemic regions of the country are the western regions of the country, in particular the Carpathian region. Kharkiv region is classified as a region with a slight iodine deficiency, but even here the prevalence of hypothyroidism remains significant. According to official data from the Kharkiv Regional Information and Analytical Center of Medical Statistics of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine for the period 2004–2017, the prevalence of hypothyroidism ranged from 224.9 to 535.5 cases per 100 thousand population. The rate of increase in incidence during this period was 8.5%. The vast majority of cases (98.4%) were registered among the adult population, of which 56.1% were among people of working age. This indicates the relevance of timely detection of SCH and its secondary prevention in young and middle-aged patients.

Hypertension (HPT) is one of the five main diagnostic criteria for MASLD. Several components of blood pressure, namely systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressure, show also a positive association with elevated TSH levels. Moreover, it is high blood pressure that is often the primary reason for patients to seek medical attention, which allows for timely detection of concomitant pathologies, including MASLD and SCH.

Chronic low-grade systemic inflammation and redox imbalance are key pathophysiological links that unite MASLD, SCH and HPT. They can both contribute to the development of these conditions and be their consequence.

Therefore, the aim of our study was to evaluate metabolic profiles, inflammatory markers, and oxidative stress parameters in hypertensive patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, depending on the presence of concomitant subclinical hypothyroidism.

Methodology

The study included 126 patients who underwent clinical and laboratory examination at the L.T. Malaya Therapy National Institute of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine (Kharkiv), during the pre-war period (2019–2022). This timeframe was chosen to minimize potential group differences related to war-related stress. Examinations were conducted in both outpatient and inpatient settings. Based on the presence of comorbid conditions, all participants were divided into four groups, comparable in age:

- Group 1 — controls (n = 30), median age of 45.7 [33.6; 51.2] years,

- Group 2 — patients with HPT and MASLD (n = 26), median age of 46.6 [39.8; 57.0] years,

- Group 3 — patients with HPT and SCH (n = 18), median age of 41.5 [33.6; 51.1] years,

- Group 4 — patients with HPT, MASLD and SCH (n = 52), median age of 48 [41.9; 56] years.

No differences were also found between groups in terms of sex distribution.

Anthropometric examination was performed on an empty stomach using an OMRON BF 511 body composition analyzer with mandatory measurements of height, body weight, waist circumference (WC) and hip circumference (HC). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the Quetelet formula.

Blood biochemical parameters were assessed using standard laboratory methods. Glucose and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels were measured, and the HOMA-IR index was calculated to evaluate insulin resistance. The lipid profile included total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). Renal function was evaluated by measuring serum creatinine and calculating the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) using the CKD-EPI formula. Liver function was assessed by determining alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), along with calculation of the Fatty Liver Index (FLI).

The degree of HPT in patients corresponded to stage I–II and severity grades 1–2, according to established classification criteria. The diagnosis of MASLD was based on liver ultrasound findings in combination with the FLI. A history of alcohol consumption and pharmacotherapy was assessed to exclude alcoholic or drug-induced liver disease. SCH was diagnosed based on elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels (4–10 mIU/L) confirmed by two measurements at a 3-month interval, in the presence of normal free thyroxine (fT4), indicating a low risk of progression to overt hypothyroidism within 10 years. TSH and fT4 levels were measured in serum using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits ‘TSH-ELISA’ and ‘fT4-ELISA’ (Khema, Ukraine).

Levels of insulin, C-reactive protein (CRP), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using certified commercial kits: “Insulin ELISA”, “C-Reactive Protein HS ELISA” (both manufactured by DRG Instruments GmbH, Germany), and “TNF-alpha ELISA BEST” (Vector-Best-Ukraine, Ukraine).

The prooxidant-antioxidant balance was assessed by the ratio of total hydroperoxides (THP) levels to total antioxidant activity (TAA), determined by the colorimetric method.

Statistical data processing was performed using the STATISTICA software package (serial number X12-53766). The Kruskal–Wallis test (p > 0.05) was used to assess the homogeneity of the study groups by age, and the Pearson χ² test (p > 0.05) was applied to evaluate gender distribution. The absence of statistically significant differences by these characteristics confirmed the comparability of the groups. Quantitative variables were presented as medians (Me) with interquartile ranges (Q1 – lower quartile, Q3 – upper quartile), i.e., Me (Q1; Q3). Qualitative variables were presented as absolute values (n) and relative frequencies (%). Group comparisons of qualitative variables were conducted using the Pearson χ² test. Correlations between variables were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Results

Relative to the control group, all other groups exhibited significantly higher BMI values (p < 0.001). Patients with MASLD, regardless of SCH status, demonstrated significantly elevated waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) (p < 0.05), primarily due to increased WC levels (p < 0.001). In comparison to patients with HPT and SCH, those with HPT and MASLD showed significantly higher levels of WC, HC, WHR, and BMI (p < 0.05). Notably, in patients with combined HPT, MASLD, and SCH, a decrease in the WHR was observed (p < 0.001), driven by an increase in HC (p < 0.05).

| Indicators | Groups | Values | p1 | p2 | p3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WC, cm | 1 | 80.0 [77.6; 87.5] | – | – | – |

| 2 | 97.5 [94.0; 105.1] | <0.001 | – | – | |

| 3 | 84.0 [75.8; 90.5] | >0.05 | <0.001 | – | |

| 4 | 96.0 [92.1; 102.0] | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 | |

| HC, cm | 1 | 98.0 [95.4; 103.3] | – | – | – |

| 2 | 104.3 [100.4; 108.1] | <0.001 | – | – | |

| 3 | 101 [94.8; 104.3] | >0.05 | 0.029 | – | |

| 4 | 107.0 [102.1; 114.0] | <0.001 | 0.036 | <0.001 | |

| WHR | 1 | 0.80 [0.77; 0.92] | – | – | – |

| 2 | 0.95 [0.90; 0.96] | <0.001 | – | – | |

| 3 | 0.84 [0.79; 0.87] | >0.05 | <0.001 | – | |

| 4 | 0.90 [0.86; 0.93] | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1 | 23.2 [21.6; 24.4] | – | – | – |

| 2 | 29.3 [27; 31.6] | <0.001 | – | – | |

| 3 | 27.2 [24.1; 28.6] | <0.001 | 0.016 | – | |

| 4 | 29.4 [27.5; 31.3] | <0.001 | >0.05 | 0.001 |

Patients with pathology (HPT, MASLD and/or SCH) demonstrated significantly higher levels of glucose (p < 0.05), HbA1c (p ≤ 0.001), insulin (p < 0.001), and HOMA-IR (p < 0.001) compared to the control group. These patients also exhibited a more atherogenic lipid profile, with elevated levels of non-HDL-C (p < 0.001), TC (p < 0.001), and LDL-C (p < 0.05), as well as reduced HDL-C levels (p < 0.05). Significantly higher levels of TG (p < 0.001) and VLDL-C (p < 0.001) were observed only in patients with MASLD. Among patients with HPT, those with MASLD had lower HbA1c levels (p < 0.001) but higher insulin levels (p < 0.05) and HOMA-IR (p < 0.05) compared to those with SCH. These two groups also differed significantly in TG (p < 0.001) and VLDL-C levels (p < 0.001). Patients with combined HPT, MASLD, and SCH showed significantly higher values of HbA1c, insulin, HOMA-IR, non-HDL-C, LDL-C, TG, and VLDL-C compared to the HPT, SCH group (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). In contrast, when compared to patients with HPT, MASLD, those with triple comorbidity (HPT, MASLD, and SCH) differed only by significantly lower HDL-C levels (p < 0.05).

| Indicators | Groups | Values | p1 | p2 | p3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate profile | Glucose, mmol/L | 1 4.94 [4.79; 5.23] | – | – | – |

| 2 5.42 [5.15; 5.79] | 0.002 | – | – | ||

| 3 5.32 [5.13; 5.63] | 0.035 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 4 5.68 [4.95; 5.87] | 0.001 | >0.05 | >0.05 | ||

| HbA1c, % | 1 5.14 [4.90; 5.23] | – | – | – | |

| 2 5.32 [5.14; 5.77] | 0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 5.76 [5.39; 5.92] | <0.001 | 0.011 | – | ||

| 4 5.96 [5.81; 6.21] | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.008 | ||

| Insulin, µIU/mL | 1 10.46 [9.44; 11.16] | – | – | – | |

| 2 24.85 [15.86; 31.8] | <0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 17.59 [13.74; 22.61] | <0.001 | 0.026 | – | ||

| 4 23.78 [18.63; 31.56] | <0.001 | >0.05 | 0.003 | ||

| HOMA IR | 1 2.34 [2.18; 2.65] | – | – | – | |

| 2 6.00 [3.53; 7.74] | <0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 4.14 [3.17; 4.81] | <0.001 | 0.021 | – | ||

| 4 6.26 [4.58; 8.39] | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 | ||

| Lipid profile | Non-HDL-C, mmol|l | 1 3.19 [2.85; 3.60] | – | – | – |

| 2 4.32 [3.74; 5.16] | <0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 4.16 [3.52; 4.46] | <0.001 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 4 5.03 [4.48; 5.77] | <0.001 | 0.005 | <0.001 | ||

| TC, mmol/L | 1 4.54 [4.30; 5.12] | – | – | – | |

| 2 5.63 [4.97; 6.39] | <0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 5.36 [4.71; 5.62] | <0.001 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 4 6.11 [5.56; 6.89] | <0.001 | 0.021 | <0.001 | ||

| TG, mmol/L | 1 0.87 [0.77; 1.17] | – | – | – | |

| 2 1.65 [1.27; 2.14] | <0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 1.08 [0.75; 1.18] | >0.05 | <0.001 | – | ||

| 4 1.68 [1.4; 2.27] | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 | ||

| VLDL-C, mmol/L | 1 0.42 [0.32; 0.59] | – | – | – | |

| 2 0.78 [0.61; 0.97] | <0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 0.46 [0.35; 0.58] | >0.05 | <0.001 | – | ||

| 4 0.87 [0.7; 1.06] | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 | ||

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1 1.39 [1.19; 1.54] | – | – | – | |

| 2 1.19 [1.05; 1.34] | 0.005 | – | – | ||

| 3 1.16 [1.06; 1.26] | <0.001 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 4 1.09 [0.91; 1.26] | <0.001 | 0.027 | >0.05 | ||

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 1 2.61 [2.46; 3.08] | – | – | – | |

| 2 3.67 [2.60; 4.40] | 0.003 | – | – | ||

| 3 3.08 [2.96; 3.68] | 0.004 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 4 4.15 [3.66; 4.69] | <0.001 | 0.028 | <0.001 |

Across all patient groups, serum creatinine levels were significantly elevated compared to the control group (p < 0.05), although no significant differences in GFR were observed. However, a significant difference in GFR was noted between patients with HPT and MASLD and those with HPT, MASLD, and SCH.

| Indicators | Groups | Values | p1 | p2 | p3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal function markers | Creatinine, μmol/L | 1 74 [67; 83] | – | – | – |

| 2 89 [80; 105] | 0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 84 [77; 95] | 0.029 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 4 94 [81; 102] | <0.001 | >0.05 | >0.05 | ||

| GFR, ml/min/1.73 m² | 1 102 [84; 110] | – | – | – | |

| 2 100 [88; 115] | >0.05 | – | – | ||

| 3 97 [82; 108] | >0.05 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 4 93 [86; 102] | >0.05 | 0.048 | >0.05 | ||

| Liver function markers | AST, U/L | 1 23 [19; 28] | – | – | – |

| 2 26 [24; 36] | 0.005 | – | – | ||

| 3 22 [18; 28] | >0.05 | 0.013 | – | ||

| 4 34 [28; 39] | <0.001 | 0.01 | <0.001 | ||

| ALT, U/L | 1 23 [19; 25] | – | – | – | |

| 2 36 [29; 52] | <0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 28 [22; 31] | 0.007 | 0.001 | – | ||

| 4 44 [35; 49] | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 | ||

| GGT, U/L | 1 40 [36; 47] | – | – | – | |

| 2 56 [49; 78] | <0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 43 [39; 54] | >0.05 | 0.001 | – | ||

| 4 71 [63; 80] | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 | ||

| ALP, nmol/(s•L) | 1 1222 [1149; 1333] | – | – | – | |

| 2 1370 [1210; 1686] | 0.006 | – | – | ||

| 3 1382 [1256; 1555] | 0.001 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 4 1562 [1414; 1741] | <0.001 | 0.034 | 0.016 | ||

| FLI | 1 21 [14; 28] | – | – | – | |

| 2 76 [68; 84] | <0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 36 [18; 49] | 0.002 | <0.001 | – | ||

| 4 79 [70; 87] | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 |

In all groups with existing pathologies, CRP and TNF-α levels were higher compared to controls. In both groups with concomitant SCH, significantly higher levels of CRP and TNF-α were observed compared to patients with HPT, MASLD. Redox imbalance was evidenced by decreased TAA, elevated THP, and the THP/TAA ratio across all pathological groups compared to controls. No significant differences were observed between the HPT, SCH and HPT, MASLD groups. However, the coexistence of all three conditions was associated with a significant increase in both THP and the THP/TAA ratio.

| Indicators | Groups | Values | p1 | p2 | p3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation markers | CRP, mg/L | 1 1.3 [0.9; 1.9] | – | – | – |

| 2 1.9 [1.4; 4.1] | 0.001 | – | – | ||

| 3 2.8 [2.5; 3.8] | <0.001 | 0.038 | – | ||

| 4 3.6 [2.6; 4.6] | <0.001 | 0.002 | >0.05 | ||

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 1 2.2 [1.64; 2.69] | – | – | – | |

| 2 2.08 [1.76; 2.64] | – | – | – | ||

| 3 3.96 [3.61; 4.84] | <0.001 | <0.001 | – | ||

| 4 4.42 [3.57; 5.29] | <0.001 | <0.001 | – | ||

| Redox balance markers | THP, μmol/L | 1 89.96 [72.98; 113.14] | – | – | – |

| 2 109.38 [92.9; 165.62] | 0.011 | – | – | ||

| 3 127.23 [101.13; 146.71] | 0.004 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 4 156.73 [136.03; 172.3] | <0.001 | 0.014 | 0.002 | ||

| TAA, μmol trolox equivalent | 1 590.23 [570.75; 620.26] | – | – | – | |

| 2 539 [396.12; 597.51] | 0.01 | – | – | ||

| 3 510.08 [423.41; 594.2] | 0.01 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 4 489.19 [404.37; 534.85] | <0.001 | >0.05 | >0.05 | ||

| THP/TAA | 1 0.16 [0.12; 0.18] | – | – | – | |

| 2 0.22 [0.16; 0.38] | 0.002 | – | – | ||

| 3 0.26 [0.17; 0.31] | 0.002 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 4 0.31 [0.27; 0.41] | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.021 |

Among patients with concurrent HPT and MASLD, the presence of SCH was associated with a range of metabolic and inflammatory alterations. In the overall cohort of patients with HPT and MASLD (with or without SCH), elevated TSH levels correlated positively with HbA1c, CRP, TNF-α, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and the THP/TAA ratio. In contrast, TSH was inversely associated with HDL-C, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), TAA, and the WHR. Among patients without SCH, TSH values remained within the euthyroid range, potentially masking the impact of TSH elevation. Therefore, further correlation analysis was limited to the subgroup with triple comorbidity (HPT, MASLD, and SCH), in which the median TSH level was significantly associated with glucose, TNF-α, and the THP/TAA ratio, and inversely associated with HDL-C, GFR, and TAA.

SCORE2 was calculated for patients aged 40 years and older with HPT and concomitant MASLD and/or SCH. The proportion of such patients was 73.1% in the HPT, MASLD group, 55.6% in the HPT, SCH group, and 82.7% in the group with combined HPT and both MASLD, SCH. A comparative analysis of SCORE2 risk categories across the groups revealed significant differences.

Discussion

The obtained anthropometric data suggest SCH is primarily associated with general obesity, as reflected by increased BMI, whereas MASLD is more closely linked to visceral adiposity. The presence of SCH in patients with concomitant HPT and MASLD is associated with elevated HC and an increased WHR, which may indicate a specific effect on adipose tissue distribution and potentially exert a protective role in the development of cardiovascular complications. It is hypothesized that these patients may exhibit a redistribution of fat toward a gynoid (lower-body) pattern, particularly in the thigh region, which could partially mitigate metabolic risk. This assumption requires further investigation.

Somewhat different results were reported in the study by Sun, Q., He, Y., and Yang, L. (2024), although their cohort included individuals with TSH values within the normal reference range, not patients with SCH. They observed a significant positive association between total percent fat (TPF) and TSH, while no significant associations were found with android percent fat (APF) or gynoid percent fat (GPF) in the overall cohort. However, in females, TSH levels were positively correlated not only with TPF, but also with APF, and GPF. While our findings similarly showed associations between TSH and increased fat accumulation compared to controls, in patients with coexisting MASLD, the contribution of SCH appeared more pronounced with respect to gynoid fat deposition.

The observed differences in body fat distribution, particularly in the context of obesity development, could potentially be explained by alterations in adipokine profiles; however, this aspect was not assessed in our study. Emerging evidence suggests that SCH may modulate adipose tissue function through changes in adipokine secretion (e.g., leptin, adiponectin, resistin), thereby influencing both inflammatory and metabolic pathways. Specifically, TSH receptor stimulation in adipocytes enhances leptin production, while leptin reciprocally promotes intracellular T3 generation by regulating deiodinase activity—forming a bidirectional TSH–leptin feedback loop. Moreover, at the central level, leptin plays a crucial role in regulating the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid (HPT) axis. This complex interaction may partially account for altered fat distribution patterns observed in patients with SCH.

In carbohydrate metabolism, SCH is associated with higher levels of HbA1c but not with insulin resistance, as confirmed by lower levels of insulin and HOMA-IR compared to patients with MASLD. Similar results were reported by Stoica R. A. et al. (2021), who found no association between thyroid function tests (TSH, fT4) and insulin resistance indices in adult Romanian women in a case-control study with one-year retrospective follow-up. Zaidi A. et al. (2024) also observed that patients with SCH showed significant differences in mean HbA1c, and HbA1c levels were positively correlated with serum TSH. However, a recent study by Yang W. et al. (2023) demonstrated that SCH increases IR in normoglycemic individuals, and that declining central thyroid sensitivity may contribute to a heightened risk of developing diabetes. The contribution of SCH to the development of insulin resistance in the context of TSH < 10 mIU/L requires further investigation. In contrast, MASLD exhibits a more pronounced metabolic syndrome, characterized by increased HOMA-IR, TG, and VLDL-C levels. This is evidenced by the absence of significant differences in these parameters when SCH is added to dual pathology, compared to significant changes observed when MASLD is added to dual pathology. Moreover, the combination of HPT, MASLD, and SCH demonstrates a cumulative negative effect, reflected by the most unfavorable lipid profile, increased HbA1c, and non-HDL-C, suggesting a possible synergistic effect of SCH and MASLD on cardiometabolic risk. These findings align with data supporting the key role of MASLD in the formation of an atherogenic metabolic profile and the ability of SCH to exacerbate dyslipidemia and hepatic insulin resistance.

Despite an increase in creatinine levels across all groups, changes in GFR were insignificant, suggesting the presence of compensatory mechanisms in mild SCH (TSH < 10 mIU/L). However, the addition of SCH in patients with existing HPT and MASLD was associated with a significant decrease in GFR—a phenomenon not observed when MASLD was added to HPT and SCH. Interestingly, Shimizu Y. et al. (2022) identified a significant inverse association between HbA1c and GFR in participants with SCH who were not receiving glucose-lowering medications, whereas no such association was found in euthyroid individuals. Therefore, renal dysfunction in patients with HPT, MASLD, and SCH may be attributable, at least in part, to endothelial impairment driven by carbohydrate metabolism abnormalities typically seen in SCH.

Elevated levels of ALP and AST in patients with combined SCH and MASLD point to a potential role of SCH in MASLD progression or biliary tract injury, warranting further investigation. It is also plausible that SCH primarily contributes to increased ALP levels, as indicated by the absence of differences in ALP between patients with HPT and MASLD versus those with HPT and SCH. It is known that in MASLD, thyroid hormone receptor (THR) activation is reduced, which may explain the presence of normal circulating thyroid hormone levels despite elevated TSH. Thyroid hormone administration has been shown to reduce hepatic triglyceride content by enhancing fatty acid utilization through lipophagy and β-oxidation, as well as lowering LDL cholesterol levels. Of particular interest are selective THR-β agonists (thyromimetics), which demonstrate reduced affinity for THR-α, thereby minimizing unwanted cardiovascular side effects. Resmetirom, a selective THR-β agonist, has shown promising results in a large phase III trial in patients with MASH (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis), including reductions in hepatic fat content, transaminase levels, and atherogenic dyslipidemia, with a favorable safety profile. The findings of our study—specifically, elevated liver enzymes and progressive dyslipidemia—suggest that such therapy may be beneficial not only in patients with established steatohepatitis but also in those with hepatic steatosis and normal transaminase levels.

Inflammatory markers, including CRP and TNF-α, were elevated in SCH groups, supporting the presence of subclinical chronic inflammation in these patients. This observation aligns with existing literature describing a prothrombotic and proinflammatory state in SCH, even in the absence of overt hypothyroidism. The inflammatory cascade may be initiated earlier by SCH than its hepatic manifestations in MASLD, as demonstrated by significantly higher proinflammatory markers in patients with SCH compared to other groups. Notably, patients with MASLD who have not yet developed pronounced steatohepatitis may exhibit lower CRP and TNF-α levels than those with SCH.

Data on redox balance reveal increased oxidative stress and diminished antioxidant capacity in patients with HPT and concomitant SCH, with a similar severity observed in those with HPT and MASLD, as evidenced by the lack of significant differences between these groups. The redox imbalance observed in patients with combined HPT, MASLD, and SCH likely reflects activation of oxidative stress primarily driven by enhanced oxidative processes. The greatest elevation in the THP/TAA ratio in the presence of all three pathologies underscores the importance of a multifactorial approach in managing such patients. It is well established that mitochondrial dysfunction leads to impaired oxidative phosphorylation and excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and mitochondria are known targets of thyroid hormones. Although serum thyroid hormone levels remain within the normal range in patients with MASLD and SCH, intracellular thyroid hormone concentrations may be reduced in MASLD. Therefore, in our study, the observed redox imbalance in patients with combined HPT, MASLD, and SCH is likely attributable to mitochondrial dysfunction induced by SCH.

The obtained data of correlation analysis indicate the potential role of elevated TSH as a mediator of metabolic homeostasis disorders in patients with combined HPT, MASLD, and SCH. In particular, elevated TSH is associated with:

- activation of low-grade systemic inflammation (increased TNF-α and CRP),

- impaired redox balance (increased prooxidant activity and decreased antioxidant defense),

- worse lipid profile (decreased HDL-C),

- hyperglycemia and potential deterioration of renal function (decreased GFR).

When patients with HPT and MASLD without SCH were included in the correlation analysis, previously undetected correlations emerged that were absent in the SCH-only group. This phenomenon may partly be attributed to the expanded range of the TSH variable, which increased variability and thus enhanced the statistical power to identify associations. Additionally, in patients with SCH, adaptive or compensatory mechanisms may modulate the expected effects of TSH. For example, physiological adaptation to mild hypothyroidism could alter tissue insulin sensitivity or modify pro-inflammatory signaling pathways. Consequently, even physiological fluctuations in TSH within the reference range may exert clinically relevant effects on the metabolic and pro-oxidant profiles of patients.

TSH might exert direct metabolic effects in peripheral tissues independent of thyroid hormone mediation, as TSH receptors are expressed in hepatocytes and adipocytes. This could partially explain TSH-associated metabolic alterations observed even in euthyroid or subclinical stages.

A significantly greater proportion of patients in the HPT, MASLD, SCH group exhibited high cardiovascular risk according to SCORE2 compared to those with HPT, MASLD alone, supporting the cumulative impact of SCH on the cardiometabolic burden. This finding underscores the additive role of SCH in exacerbating cardiovascular risk beyond the contributions of HPT and MASLD alone. Several mechanisms may account for the deleterious cardiovascular effects of impaired thyroid function, including dysregulation of adipocytokines, endothelial dysfunction, impaired cardiac contractility, and diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle both at rest and during exertion. However, the extent to which these mechanisms are expressed—or potentially amplified—in the context of MASLD remains poorly understood and warrants further investigation.

In the present study, we did not analyze the impact of the sequence of disease onset (MASLD or SCH) or the duration of this comorbidity on the observed differences between groups. The main reason was the frequent inability to determine which condition developed first in patients with hypertension, as both were often diagnosed simultaneously during screening. However, we believe that the omission of these factors likely did not significantly affect the observed intergroup differences. On the one hand, SCH appears more frequently in patients with liver disease: those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) exhibit a significantly higher incidence of hypothyroidism compared to individuals without NAFLD. On the other hand, according to another study, SCH was associated with an increased risk of developing MASLD. These findings support the notion that the relationship between MASLD and low thyroid function is independent. Therefore, in our study, the lack of analysis regarding the order and duration of MASLD or SCH likely had minimal impact on the differences in metabolic profile, inflammatory, and oxidative stress markers. The bidirectional risk between SCH and MASLD deserves longitudinal follow-up.

Conclusions

This study highlights the complex and multifactorial role of subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) in modulating metabolic, inflammatory, and redox homeostasis in patients with concomitant hypertension (HPT) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). While SCH alone is primarily associated with general obesity and elevated HbA1c—without overt insulin resistance—its coexistence with HPT and MASLD significantly amplifies systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, dysglycemia, and atherogenic dyslipidemia. These effects are evidenced by elevated CRP, TNF-α, ALP, and THP/TAA ratios, and decreased HDL-C levels, even in the context of mild thyroid dysfunction (thyroid-stimulating hormone, TSH < 10 mIU/L).

Notably, the presence of triple comorbidity (HPT, MASLD, SCH) is linked to the most unfavorable metabolic and biochemical profiles, suggesting a cumulative—and potentially synergistic—effect on cardiometabolic risk.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

The author have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Younossi ZM, Kalligeros M, Henry L. Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2024;31(Suppl):S32-S50. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2024.0431

2. Kotseva K, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, et al. Primary prevention efforts are poorly developed in people at high cardiovascular risk: A report from the European Society of Cardiology EURObservational Research Programme EUROASPIRE V survey in 16 European countries. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2021;28(4):370-379. doi: 10.1177/2047487320908698

3. Ansu Baidoo V, Knutson KL. Associations between circadian disruption and cardiometabolic disease risk: a review. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023;31(3):615-624. doi: 10.1002/oby.23666

4. Pu S, Zhao B, Jiang Y, Cui X. Hypothyroidism/ subclinical hypothyroidism and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: advances in mechanism and treatment. Lipids Health Dis. 2025;24(1):1-6. doi: 10.1186/s12944-025-02474-0

5. Yuan S, Ebrahimi F, Bergman D, et al. Thyroid dysfunction in MASLD: Results of a nationwide study. JHEP Rep. 2025;7(5):101369. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2025.101369

6. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T4, and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):489-499. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8182

7. Wyne KL, Nair L, Schneiderman CP, et al. Hypothyroidism prevalence in the United States: a retrospective study combining national health and nutrition examination survey and claims data, 2009–2019. J Endocr Soc. 2023;7(1):bvac172. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvac172

8. Mendes D, Alves C, Silverio N, Marques FB. Prevalence of undiagnosed hypothyroidism in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Thyroid J. 2019;8(3):130-143. doi: 10.1159/000499751

9. Podavalenko AP, Goncharova OA, Pashchenko LS. Epidemiological analysis of hypothyroidism prevalence in Kharkiv region. Int Endocrinol J. 2019;15(1):32-37. doi: 10.22141/2224-0721.15.1.2019.158690

10. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Obes Facts. 2024;17(4):374-443. doi: 10.1159/000539371

11. Wang X, Wang H, Yan L, et al. The positive association between subclinical hypothyroidism and newly-diagnosed hypertension is more explicit in female individuals younger than 65. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2021;36(4):778-789. doi:10.3803/EnM.2021.1101

12. Møller S, Kimer N, Hove JD, Barløse M, Gluud LL. Cardiovascular disease and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: pathophysiology and diagnostic aspects. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2025:zwae306. doi:10.1093/eurjpc/zwae306

13. Tellechea ML. Meta-analytic evidence for increased low-grade systemic inflammation and oxidative stress in hypothyroid patients. Can levothyroxine replacement therapy mitigate the burden? Endocrine. 2021;72:62-71. doi:10.1007/s12020-020-02484-1

14. Wang P, Zhang W, Liu H. Research status of subclinical hypothyroidism promoting the development and progression of cardiovascular diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2025;12:1527271. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2025.1527271

15. Alamdari DH, Paletas K, Pegiou T, Sarigianni M, Befani C, Koliakos G. A novel assay for the evaluation of the prooxidant–antioxidant balance, before and after antioxidant vitamin administration in type II diabetes patients. Clin Biochem. 2007;40(3-4):248-254. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.10.017

16. Sun Q, He Y, Yang L. The association of thyroid stimulating hormone and body fat in adults. PLoS One. 2024;19(12):e0314704. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0314704

17. Pingitore A, Gaggini M, Mastorci F, Sabatino L, Cordiviola L, Vassalle C. Metabolic Syndrome, Thyroid Dysfunction, and Cardiovascular Risk: The Triptych of Evil. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(19):10628. doi:10.3390/ijms251910628

18. Stoica RA, Ancuceanu R, Costache A, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism has no association with insulin resistance indices in adult females: A case-control study. Exp Ther Med. 2021;22(3):1033. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10465

19. Zaidi A, Elmghirbi W, Algdar A, Saleh H. Association Between Subclinical Hypothyroidism and HbA1c Levels in Non-Diabetic Patients: A Case-Control Study. Libyan Med J. 2024;16(2):106-110.

20. Yang W, Jin C, Wang H, Lai Y, Li J, Shan Z. Subclinical hypothyroidism increases insulin resistance in normoglycemic people. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1106968. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1106968

21. Chng CL, Goh GB, Yen PM. Metabolic and Functional Cross Talk Between the Thyroid and Liver. Thyroid. 2025;35(6):607-623. doi: 10.1089/thy.2025.0178

22. Shimizu Y, Kawashiri SY, Noguchi Y, et al. Effect of subclinical hypothyroidism on the association between hemoglobin A1c and reduced renal function: a prospective study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(2): 462. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12020462

23. Ratziu V, Scanlan TS, Bruinstroop E. Thyroid hormone receptor-β analogs for the treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH). J Hepatol. 2024;82(2):375-387. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2024.10.018

24. Xu Q, Wang Y, Shen X, Zhang Y, Fan Q, Zhang W. The effect of subclinical hypothyroidism on coagulation and fibrinolysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:861746. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.861746

25. Torres EM, Tellechea ML. Biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and cytokine levels in hypothyroidism: a series of meta-analyses. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2025;20(2):119-128. doi:10.1080/17446651.2024.2438997

26. Ramanathan R, Patwa SA, Ali AH, Ibdah JA. Thyroid hormone and mitochondrial dysfunction: therapeutic implications for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Cells. 2023;12(24):2806. doi:10.3390/cells12242806

27. Zhu P, Lao G, Chen C, Luo L, Gu J, Ran J. TSH levels within the normal range and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality among individuals with diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):254. doi:10.1186/s12933-022-01698-z

28. Loosen SH, Demir M, Kostev K, Luedde T, Roderburg C. Incidences of hypothyroidism and autoimmune thyroiditis are increased in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;33(1S):e1008-e1012. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002136

29. Wang S, Xia D, Fan H, et al. Low thyroid function is associated with metabolic dysfunction‐associated steatotic liver disease. JGH Open. 2024;8(2):e13038. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.13038