Metabolomics: Insights for Disease Mechanisms & Biomarkers

Metabolomics: Analytical Insights into Disease Mechanisms and Biomarker Discovery

Manendra Singh Tomar 1, Mohit 1,2, Anshuman Srivastava 1, Ankit Pateriya 1, Fabrizio Araniti 3, Ashutosh Shrivastava 1*

- Center for Advance Research, Faculty of Medicine, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow-226003, Uttar Pradesh, India

- Department of Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dental Sciences, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow-226003, Uttar Pradesh, India

- Dip. di Scienze agrarie e ambientali, Produzione, Territorio, Agroenergia (Di.S.A.A.) Università degli Studi di Milano Via Celoria, 2- 20133 MILANO – ITALY

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 June 2025

CITATION: Tomar, MS., Mohit., et al., 2025. Metabolomics: Analytical Insights into Disease Mechanisms and Biomarker Discovery. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(6). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6549

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6549

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Metabolomics is an interdisciplinary field that combines advanced analytical chemistry techniques with biology to comprehensively identify and quantify metabolites present in cells, tissues, and biofluids. It serves as a powerful tool for understanding the biochemical underpinnings of various physiological and pathological processes. By capturing the dynamic changes in the metabolome, this approach offers a snapshot of the functional state of biological systems. Over the past decade, metabolomics has been extensively employed in the search for novel biomarkers that are clinically relevant, aiding in early diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring. Recent advancements in technologies such as mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy have significantly enhanced the sensitivity, accuracy, and throughput of metabolomic studies. These developments have contributed to a deeper understanding of the roles metabolites play in human pathophysiology. This review presents an updated overview of the latest techniques and analytical strategies used in metabolomics research. It also highlights the application of metabolomics in exploring metabolic alterations associated with neurological conditions, cancer, and lifestyle diseases including diabetes and coronary heart disease. The broad impact and growing utility of metabolomics hold great promise for driving innovation in disease prevention, personalized treatment strategies, and improved healthcare outcomes.

Keywords:

Metabolomics, Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry, Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, Biomarkers

1. Abbreviations:

- AD: Alzheimer disease

- CI: Chemical ionization

- CHD: Coronary heart disease

- EI: Electron ionization

- GMS: Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- LC-MS: Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance

- PCA: Principal component analysis

- PLS-DA: Partial least square discriminant analysis

- sPLS-DA: Sparse partial least square discriminant analysis

- OPLS-DA: Orthogonal partial least square discriminant analysis

- PD: Parkinson disease

- T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Introduction

The rapidly developing field of metabolomics applies cutting-edge analytical chemistry and intricate statistical methods to define the metabolome. This field, which emerged after genomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics, employs high-throughput techniques and bioinformatics to investigate cellular metabolism. Focusing on metabolites—key metabolic intermediates and products—this field covers both quantitative and qualitative analyses. Metabolites, essential for energy production, cell signaling, and programmed cell death, act as precursors and by-products. They may be endogenous or exogenous, derived from the organism or from external sources like food or environmental chemicals. Metabolites include molecules such as sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids and can extend to xenobiotics like pharmaceuticals and pollutants. Metabolomics precise molecular phenotyping has led to its successful application in various scientific domains such as chemistry and medicine. It is considered as a leading technique in biomarker discovery.

People often overlook the extensive regulatory functions of metabolites, viewing them merely as gene and protein products. Metabolomics aims to track metabolism changes over time to pinpoint physiological or disease outcomes and profiles a vast array of small molecules across different samples like serum and urine. This article first outlines the state-of-the-art in high-throughput metabolomics, analysis types, and data processing. Later sections explain its application in understanding and addressing complex diseases such as diabetes and cancer, thus revolutionizing healthcare via the “P4” approach—prediction, prevention, personalization, and participation.

To date, metabolomics has enhanced research in biomarker identification, nutrition, drug development, and pharmacology. This article talks about breaking down the metabolome to learn more about the individual metabolites and how they work together for therapeutic purposes, which can help with diagnosing diseases, predicting their prognoses, and creating personalized treatments. Metabolomic studies also help identify biomarkers for various diseases.

1. Metabolomics and Types of Analysis

The term “metabolome” describes all low-molecular-weight compounds vital for cellular functions and metabolic processes in organisms. Metabolomics is valuable for biomarker discovery in disease research. It detects changes due to diseases, drug reactions, or environmental factors like diet and lifestyle, offering insights into the mechanisms of complex diseases and aiding in the development of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Early detection of metabolomic changes could allow diagnosis in asymptomatic stages, which could lead to better treatment outcomes and a lower mortality rate.

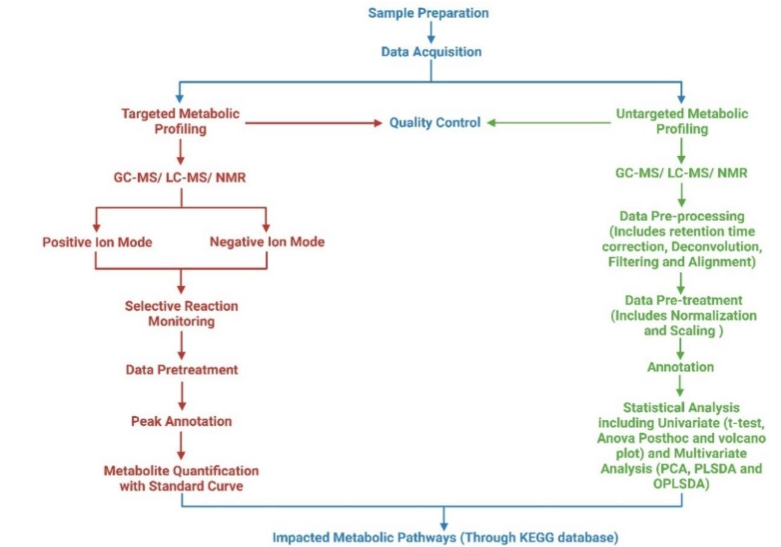

In metabolomics research, teams employ either an untargeted or targeted approach. Untargeted metabolomics aims to identify as many metabolites as possible to discern phenotypic patterns, aiding in biomarker discovery. Targeted metabolomics focuses on specific metabolites or classes, such as lipids or tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolites. Advancements in metabolomic biomarker analysis could revolutionize diagnosis and treatment strategies, enhancing patient-specific therapies. Metabolomics typically uses complex biological matrices like blood or urine, requiring careful sample preparation and analytical techniques to ensure comprehensive metabolite detection despite their physicochemical diversity. Combining different methods is essential to overcome analytical biases and achieve extensive metabolite coverage.

i. GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY-MASS SPECTROMETRY

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) is a widely utilized tool in metabolomics. Due to the need for volatile and thermally stable analytes in the high-temperature oven environment of GC-MS, derivatization is often necessary to prepare samples for analysis. This additional step can result in metabolite loss, a significant disadvantage of the method. When samples enter the source of GC-MS, they are ionized either by electron impact (EI) or chemical ionization (CI). This allows for both untargeted and targeted metabolomics through full scan and selected ion monitoring modes. The unique spectrum patterns of substances and the extensive online spectral libraries make GC-MS highly effective. Also, the fact that GC retention times are the same on all machines makes it easier to search databases for unknown metabolites, even though there are some problems, such as a limited mass range and frequent non-detection of molecular ions due to fragmentation.

Scientists are now using two-dimensional GC (GC-GC) and combining GC with time-of-flight (TOF) mass analyzers to find and separate complex metabolite mixtures more easily. This makes chemical identification more accurate. Various detectors, including triple quadrupoles and quadrupole-time of flight, are employed in GC-MS, facilitating a range of applications from sample preparation to data processing in metabolomics. Moreover, in the study of primary metabolites with high boiling points, such as glucose, lactate, etc., it is important to use methods such as trimethylsilylation and changing carbonyl groups into oximes.

Gas chromatography/electron ionization-mass spectrometry mostly uses TOF mass analyzers and quadrupole instruments for quick identification rather than high-mass resolution. High-resolution TOF-MS is crucial for finding unknowns. The TOF-MS instruments, for example, offer rapid data acquisition at moderate mass resolution. However, mainstream metabolomic research has not widely adopted ion trap devices.

ii. LIQUID CHROMATOGRAPHY-MASS SPECTROMETRY

Metabolomics is the study of finding and measuring small molecules that are important for metabolic processes. Researchers are increasingly using LC-MS due to its high throughput, soft ionization techniques, and ability to analyze a wide range of metabolites. The success of LC-MS-based metabolomic studies often hinges on a combination of experimental, analytical, and computational procedures. Its popularity has grown because of its high sensitivity, adaptability, the avoidance of chemical derivatization, and the introduction of new ionization methods. This study focuses on untargeted metabolomics, which is considered hypothesis-generating due to its potential for discovering novel metabolites in research settings.

Mass spectrometry provides highly sensitive and selective quantitative analysis and the potential for compound identification. Various atmospheric pressure ionization (API) methods, such as electrospray ionization (ESI), atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI), and atmospheric pressure photoionization (APPI), facilitate the ionization of different metabolite classes in both positive and negative modes. ESI is often preferred for profiling unknown metabolites because it generally results in intact molecule ions and helps in their initial identification. Similarly, APCI and APPI, which usually cause little to no fragmentation, are robust and handle high buffer concentrations well. These ionization techniques are also useful for studying non-polar and thermally stable substances, like lipids. Configurations combining ESI with APCI or APPI have recently become a trend. The LC-MS has been applied in various studies, such as analyzing urine samples in toxicity studies, genetic research, plasma analyses, and detecting new substrates of fatty acid amide hydrolase in metabolic fingerprinting of brain and spinal cord extracts.

iii. NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, which is based on the energy absorbed and re-emitted by certain atomic nuclei in a magnetic field, has detection limits ranging from µM to nM. It can non-destructively quantify and identify a diverse array of substances and is capable of automated, rapid analyses of small molecules in the metabolome. The NMR data provide reproducible metabolite profiles and can offer additional structural insights, including information on chemical functional groups and their spatial arrangement. This technique helps elucidate biological processes and biochemical pathways, although its relatively low sensitivity limits its ability to detect scarce metabolites compared to mass spectrometry (MS). Recent technological improvements have enhanced NMR’s sensitivity and system hardware. Unlike MS, NMR’s sensitivity is unaffected by metabolites’ acid-base properties or hydrophobicity, allowing broader metabolome coverage in a single analysis. Moreover, NMR is advantageous for high-throughput, untargeted metabolomics due to simple sample preparation and rapid processing, but it is less commonly used than MS. It is particularly effective in identifying organ-specific toxicity, monitoring toxicological progression, and identifying toxicity biomarkers. Various biospecimens including tissues, biofluids, and different cell types can be analyzed using NMR, making it a versatile tool for investigating cellular processes. Metabolomics frequently analyzes blood serum/plasma, urine, and saliva, which are easily obtained and rich in biological information.

2. Data Analysis Approach for Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics:

The data export process in metabolomics aims to standardize metabolite profiling formats. Some important preprocessing steps are noise reduction, peak detection, and data alignment to identify and label metabolites. Various software, both free and paid, supports data export and analysis. Databases provide access to retention time, mass, and MS/MS data, aiding compound detection. For instance, GC-MS data can be found in the NIST MS database, and LC-MS data in the METLIN database, which houses over 10,000 MS/MS spectra.

Post-extraction, metabolomics data undergo univariate and multivariate statistical analyses. Before multivariate analysis, data must be preprocessed through normalization, transformation, and scaling. Depending on the number of metabolite features, we apply techniques like quantile normalization. Data transformations include logarithmic, square, and cube root adjustments. Common scaling methods include mean centering, auto, Pareto, and range scaling. These extensive data sets from mass spectrometry necessitate multimodal statistical methods for thorough analysis.

Univariate analysis involves statistical tests using a single independent variable, often applied in omics studies. We include techniques like correlation analysis, fold change, t-test, ANOVA, and regression analysis. Procedures exist to assess association degrees between data sets, with results often shown as a heatmap. When normal distribution assumptions fail, we use non-parametric tests like the Kruskal-Wallis to determine significance. In metabolomics, fold change studies analyze the ratio of mean metabolite abundances between two groups. Two-sample t-tests are deployed to compare these means, rejecting the null hypothesis where p-value is below 0.05. The Tukey HSD post-hoc test is used for both multivariate and one-way ANOVA. The FDR approach by Benjamini and Hochberg is used to fix p-values for multiple testing. Univariate regression can identify phenotype-related signals in full resolution or binned spectra.

Multivariate analyses like principal component analysis (PCA), partial least square discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), sparse partial least square discriminant analysis (sPLS-DA), and orthogonal partial least square discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) clarify metabolomics data by identifying key spectral features. Data dimensionality can be reduced using PCA, an unsupervised method that preserves information crucial for understanding underlying patterns. Longitudinal studies often use PCA to analyze intra- and inter-subject variance and identify systematic changes across different research phases. Despite its wide use, PCA’s limitations include lacking predictive capability and difficulty handling missing data. Due to its robustness in handling large, noisy datasets, metabolomics increasingly uses PLS-DA to optimize sample segregation by correlating two data matrices. It also allows for feature selection and classification, essential for food authentication and clinical diagnosis. However, its misuse in discriminant analysis calls for careful cross-validation to avoid overfitting. Sparse partial least squares-discriminant analysis extends PLS for classification purposes, ensuring model generalization and appropriate variable selection. It integrates into a generalized linear model for handling uneven class sample sizes, enhancing sparse variable selection and dimension reduction in survival data analysis. Orthogonal partial least square discriminant analysis models differentiate experimental groups in metabolomics by analyzing spectrum-based metabolite variations and identifying biologically significant changes.

1. METABOLOMICS AS THE DRIVER OF BIOMARKER ANALYSIS:

Metabolomics analyzes small molecules, or metabolites, in biological samples like blood, urine, or tissue to understand metabolic states. It is a potent tool for biomarker analysis, identifying molecules that indicate disease presence or severity. Metabolomics provides insights into metabolic changes due to disease, treatment, or environmental factors. We can identify metabolites related to disease or treatment by comparing metabolite profiles between groups, such as healthy versus diseased or treated versus untreated. These metabolites are then validated as biomarkers for disease diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring. Used in diseases like cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases, metabolomics offers advantages like higher specificity and sensitivity compared to traditional biomarkers. Metabolomics is instrumental in personalized medicine, facilitating early detection and tailored treatment of diseases.

2. METABOLOMICS APPLICATION IN DISEASE BIOMARKER DISCOVERY:

i. Cancer:

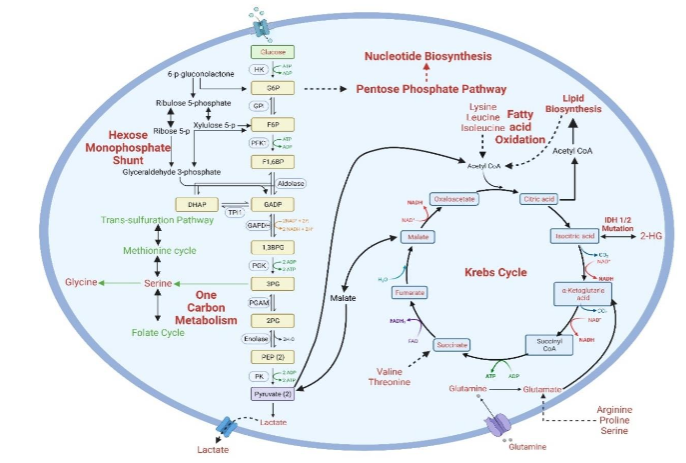

Metabolic alterations in cancer cells are crucial for their growth and development. Cancer cells alter their metabolic pathways to meet the increased demands for bioenergetics and biosynthesis and mitigate reactive stress. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (PET) and other metabolites in biological samples are recognized for their potential in tumor detection and treatment monitoring. Metabolomic profiling effectively assesses tumor metabolism dynamics and therapeutic outcomes. Advanced spectrometric methods enable the detection of metabolic characteristics in metastatic cancer cells, revealing changes over time and space. Combined genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses with metabolomics have identified potential diagnostic metabolic markers in various cancers. Otto Warburg first highlighted the importance of cellular metabolism in cancer in the early 20th century, noting higher lactate in tumors. Recent studies challenge the universal applicability of the Warburg effect; for example, glioblastoma cells exhibit both glutamine metabolism and the Warburg effect and rely on pyruvate carboxylase for development.

Drug-resistant and metastatic cancers upregulate oxidative phosphorylation, indicating its therapeutic potential. Fatty acid oxidation is vital for the survival of some lymphomas. Enhanced pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) activity is needed to make nucleotides and NADPH, which helps tumors grow quickly and gets rid of superoxide radicals. The amounts of N-acetyl-histidine, phospholipids, and dehydroascorbic acid were altered in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Prostate cancer studies reveal abnormalities in citrate, choline, and amino acids. Gastric cancer patients’ fasting lipid profiles show lower levels of cholesterol and apolipoproteins compared to healthy controls. Elevated levels of amino acids are associated with bladder cancer progression. These studies demonstrate how metabolism interacts with cancer immunity, influencing immunological responses through nutrient metabolism.

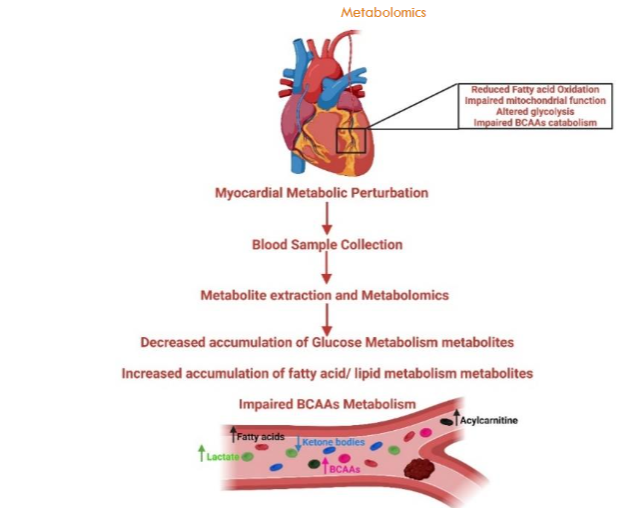

ii. Coronary Heart Diseases:

Research has highlighted metabolites differentially expressed in individuals with and without CHD, underscoring metabolomics potential in pinpointing obstructive CHD biomarkers through differential analysis. Metabolomics techniques have successfully identified altered amino acids, fatty acids, and lipid levels in CHD patients, which can serve as early detection biomarkers. Additionally, this approach helps predict CHD risk and monitor disease progression by analyzing blood or urine for metabolites linked to higher CHD risks, facilitating personalized treatment strategies. Metabolomics’ identified increased homocysteine levels have been correlated with higher CHD risk.

Moreover, recent metabolomics research has extended to understanding biochemical pathways underlying CHD, aiming at biomarker identification for early detection and severity assessment, notably in special populations like those with type 2 diabetes or obesity. These studies have uncovered metabolites like branched-chain amino acids and acylcarnitines, significantly associated with increased CHD risk in obese individuals. In summary, as metabolomics evolves, its significant contributions to CHD management, including biomarker identification, disease monitoring, and therapy customization, become increasingly vital in addressing cardiovascular health challenges. This advancement promises enhanced management of CHD and potentially other cardiovascular conditions.

iii. Neurological Diseases:

This research delves into the metabolomics of neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), tethered cord syndrome, spina bifida, stroke, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, glioblastoma, and disorders with metabolic defects. In this review we have mainly focused on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

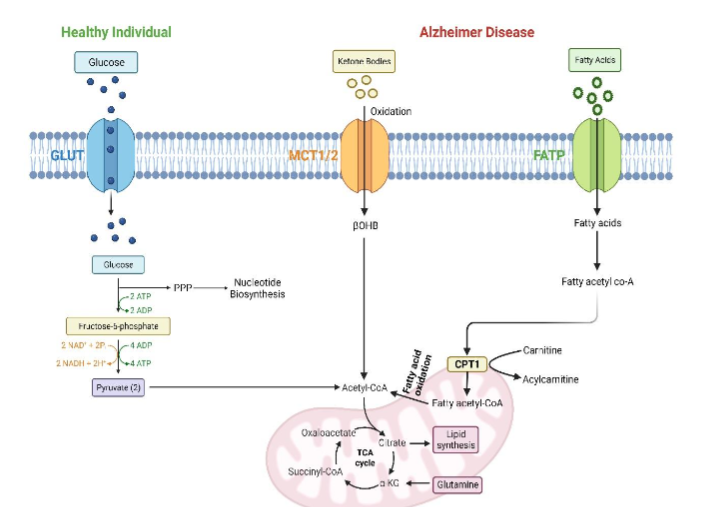

a. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD):

Metabolic anomalies, both centrally and peripherally, mark AD by metabolic anomalies, both centrally and peripherally. Numerous studies have employed various materials and methods to identify AD biomarkers. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is commonly used in AD metabolomics, serving as a central nervous system barrier and nutrient delivery system. The CNS’s influence on CSF makes metabolic changes due to the disease more detectable. Researchers have found that people with Alzheimer’s have higher amounts of glycerolipids, amino acids, and acylcarnitines in their brains and blood. Brain hypometabolism has been observed to start about 20 years before the clinical symptoms of AD, pointing the metabolic dysfunction could contribute to its development. The brain, while constituting only about 2% of body weight, consumes approximately 20% of total glucose. In conditions of reduced glucose availability, there may be a shift to alternative energy sources such as lipids.

Metabolomics show AD’s metabolic instability and decreased glucose utilization. Glycolytic impairment may lead to the utilization of ketones and fatty acids. Changes in the levels of amino acids and acylcarnitine have been seen in metabolic and other large-scale data from people with AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and healthy controls. There are different amounts of sphinganine-1-phosphate, ornithine, and other compounds in the saliva of AD patients compared to healthy controls. Metabolomics also supports changes in bioenergetic pathways, cholesterol metabolism, neuroinflammation, and osmoregulation in AD. Metabolites linked to tau phosphorylation, amyloid-beta metabolism, and other processes reveal genotype-phenotype relationships through metabolomic studies. Both targeted and untargeted studies provide quantitative data on metabolites implicated in AD, aiding the identification of reliable diagnostic biomarkers.

b. Parkinson’s Disease:

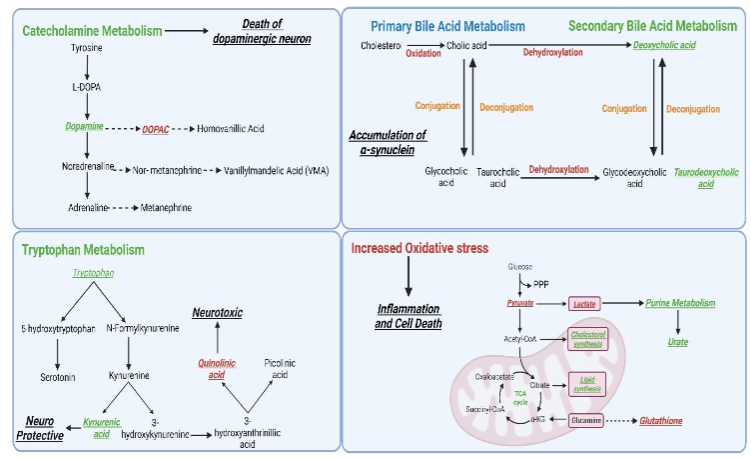

Parkinson’s disease (PD), a prevalent neurodegenerative disorder of the central nervous system (CNS), mainly affects the elderly, with its incidence increasing due to the expanding aging population. The lack of reliable biomarkers currently challenges diagnosis and treatment. Notably, metabolites are considered promising candidates for revealing disease phenotypes, closely reflecting physiological and pathological states. Studies in PD patients have found significant metabolic variations in purine, fatty acid metabolism, and dopamine metabolite homovanillic acid in plasma and CSF. Urinary metabolomics revealed differences in the metabolism of branched-chain amino acids, glycine, tryptophan, phenylalanine, and steroid hormones. The CSF studies linked PD-specific metabolic changes to antioxidative responses, glycations, and inflammation, with increased 3-hydroxykynurenine and decreased oxidized glutathione levels observed.

Clinical and experimental data underscore the impact on lipid, energy metabolism (TCA cycle, glycolysis, PPP, BCAA, acylcarnitines), fatty acids, bile acids, polyamines, and amino acids in PD, highlighting the importance of conducting validation studies and large-scale population studies to confirm these findings and identify effective biomarkers. Sebum analysis showed alterations in lipid-related pathways, including carnitine shuttle and sphingolipid metabolism. In PD patients, metabolomic profiles showed lower amounts of free fatty acids and caffeine metabolites but higher amounts of bile acids and harmful microbiota-derived metabolites. These results show that oxidative stress, which changes bilirubin/biliverdin ratios and ergothioneine levels. Metabolomic research has repeatedly highlighted connections between metabolic alterations and four key biological processes in PD: neurological diseases, inflammation, ATP concentration, and metabolic disorders. Additionally, studies have highlighted the role of polyamine pathways in neurodegeneration. N8-acetyl spermidine levels were higher in fast-progressing PD patients than in controls or slow-progressing cases. Disruptions in amino acid metabolism and a shift from the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to glycolysis were noted, alongside changes in other pathways like the urea cycle. The onset of PD involves decreased PPP enzyme activity and a lack of antioxidant reserves. Neurons in Parkinson’s disease can’t speed up glycolysis because their mitochondria aren’t working right. Instead, it gets lactate from astrocytes, and astrocytic PDH phosphorylation slows down glucose flow in TCA cycle.

iv. Diabetes:

The increasing prevalence of diabetes globally poses significant health challenges. Tailored prevention and treatment of diabetes can be enhanced through biomarker discovery, which aids in early detection, diagnosis, and disease management. Metabolomics has identified potential biomarkers for type 2 diabetes (T2DM), such as branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), aromatic amino acid metabolites, and molecules related to energy and lipid metabolism. These biomarkers, including BCAAs, aromatic amino acids, and acylcarnitines, correlate strongly with insulin resistance in T2DM. The large neutral amino acid transporter (LNAA) facilitates the cellular transport of these amino acids. In contrast, BCAAs can inhibit the uptake of aromatic amino acids, elevating their plasma levels and affecting neurotransmitter synthesis. This process is linked to obesity and depression due to neurotransmitter alterations. Additionally, BCAA metabolite accumulation may negatively impact pancreatic islet β-cells or adipocytes, activating the mTOR kinase, and is associated with increased risks of renal and hepatic dysfunction.

Research on β-oxidation dysregulation has advanced the understanding of the dysglycemic phenotype. Elevated fatty acid levels are associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and reduced glucose tolerance, mirroring patterns observed in genetic rat models. Lipid classes such as glycerolipids, (lyso) phosphatidylethanolamines, and ceramides have been linked to a higher diabetes risk. Dyslipidemia in diabetes is characterized by high plasma triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol, and elevated small dense LDL cholesterol, not associated with higher total cholesterol levels, likely due to increased free fatty acid release from insulin resistance. Acetoacetate production from free fatty acids is also linked to insulin resistance and diabetes. Untargeted metabolic studies have further identified changes in glucose, fat, and bile acid metabolism in T2DM, possibly contributing to coronary artery disease. Similar metabolic shifts were observed in insulin-resistant T2DM mice on a high-fat diet. Identifying metabolomic profiles in obese individuals at risk for metabolic diseases like T2DM could facilitate early intervention and treatment. More research is necessary to ascertain the predictive value of these metabolic biomarkers for diabetes development and their causal relationships with insulin resistance.

Future Perspectives in Metabolomics: Integration, Standardization, and Clinical Application

Metabolomics is experiencing rapid growth, with significant implications for clinical prognosis and diagnosis. One of the key challenges in the field is the lack of standardized protocols in sample collection, preparation, and analysis. Developing comprehensive, standardized methods is crucial to ensure consistent, reliable results and to facilitate cross-study comparisons, which are essential for advancing clinical applications.

Integrating metabolomics with broader omics technologies such as genomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics promises a more holistic understanding of biological systems and disease mechanisms. This multi-omics approach is expected to enhance the precision of biomarker discovery, improve diagnostics, and facilitate personalized therapeutic strategies. Additionally, integrating metabolomics data with clinical data, imaging, and other omics data could enable the development of more accurate diagnostic and prognostic models.

Technological advancements will likely improve metabolomic analyses’ sensitivity, specificity, and throughput. The development of more sophisticated high-throughput screening methods and advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence will enable more effective handling and interpretation of large-scale metabolomic data sets. These innovations will refine the accuracy of metabolomic profiling and expand its applicability across various biological samples and conditions.

The clinical applications of metabolomics are set to broaden, particularly in the realms of early disease detection, real-time monitoring of disease progression, and evaluation of treatment responses. Developing non-invasive techniques for metabolomic profiling, such as advanced breath analysis and enhanced biofluid sampling, will likely increase the clinical utility of metabolomics, making it a routine part of disease diagnosis and monitoring.

Furthermore, establishing comprehensive, standardized global metabolomics databases will be crucial for enhancing the comparability and reproducibility of metabolomics studies worldwide. Such databases would facilitate collaborative research, allowing for faster and more widespread scientific discoveries and clinical innovations.

Addressing metabolomics research’s ethical, legal, and social implications will also be vital, especially concerning data privacy, informed consent, and the implications of personalized medicine. As metabolomics moves closer to the forefront of clinical practice, these considerations will play a crucial role in shaping policies and protocols to safeguard patient interests while promoting scientific advancement.

Metabolomics in clinical diagnosis and prognosis appears promising. Research and development in the field are predicted to transform medical research and clinical practice by improving diagnosis, treatment, and patient outcomes.

Conclusion:

Metabolomics has emerged as a transformative force in clinical diagnosis and prognosis, providing a comprehensive view of an individual’s health status through detailed metabolic profile analysis. This approach is revolutionizing the field of precision medicine by enabling the identification of novel biomarkers and facilitating the monitoring of disease progression across a spectrum of conditions, including cancer, diabetes, and neurological diseases. One of the major strengths of metabolomics is its ability to provide a real-time, dynamic snapshot of metabolic changes in response to disease, treatment, or lifestyle alterations. Unlike genomics or proteomics, which offer a more static view of genetic or protein statuses, metabolomics captures the fluxes in metabolic pathways, thereby providing actionable insights into disease pathogenesis and response to therapy. Metabolomics enables the precise identification of metabolic disturbances, paving the way for the discovery of novel therapeutic targets and the design of personalized interventions that enhance clinical outcomes and improve patients’ quality of life. Looking forward, the role of metabolomics in clinical settings is set to grow, underpinned by ongoing advancements in metabolite detection technologies and data integration techniques.

Funding:

Manendra Singh Tomar is the recipient of Senior research fellowship from the University Grants Commission, Government of India, New Delhi.

Author’s Contributions:

AS and MST conceptualized, wrote and evaluated the review manuscript. M, ANS, AP and FA wrote the manuscript. All authors concur to the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interest:

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References:

- German JB, Hammock BD, Watkins SM. Metabolomics: building on a century of biochemistry to guide human health. Metabolomics : Official journal of the Metabolomic Society. 2005;1(1):3-9.

- Dar MA, Arafah A, Bhat KA, et al. Multiomics technologies: role in disease biomarker discoveries and therapeutics. Briefings in functional genomics. 2023;22(2):76-96.

- Aderemi AV, Ayeleso AO, Oyedapo OO, Mukwevho E. Metabolomics: A Scoping Review of Its Role as a Tool for Disease Biomarker Discovery in Selected Non-Communicable Diseases. Metabolites. 2021;11(7).

- Johnson CH, Ivanisevic J, Siuzdak G. Metabolomics: beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2016;17(7):451-459.

- Johnson CH, Patterson AD, Idle JR, Gonzalez FJ. Xenobiotic metabolomics: major impact on the metabolome. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2012;52:37-56.

- Kim HM, Kang JS. Metabolomic Studies for the Evaluation of Toxicity Induced by Environmental Toxicants on Model Organisms. Metabolites. 2021;11(8).

- Whitfield PD, German AJ, Noble PJ. Metabolomics: an emerging post-genomic tool for nutrition. The British journal of nutrition. 2004;92(4):549-555.

- Bino RJ, Hall RD, Fiehn O, et al. Potential of metabolomics as a functional genomics tool. Trends in plant science. 2004;9(9):418-425.

- Wishart DS. Emerging applications of metabolomics in drug discovery and precision medicine. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2016;15(7):473-484.

- Rinschen MM, Ivanisevic J, Giera M, Siuzdak G. Identification of bioactive metabolites using activity metabolomics. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2019;20(6):353-367.

- Liu X, Locasale JW. Metabolomics: A Primer. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2017;42(4):274-284.

- Zamboni N, Saghatelian A, Patti GJ. Defining the metabolome: size, flux, and regulation. Molecular cell. 2015;58(4):699-706.

- Gika HG, Zisi C, Theodoridis G, Wilson ID. Protocol for quality control in metabolic profiling of biological fluids by U(H)PLC-MS. Journal of chromatography B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences. 2016;1008:15-25.

- Ashrafian H, Sounderajah V, Glen R, et al. Metabolomics: The Stethoscope for the Twenty-First Century. Medical principles and practice : international journal of the Kuwait University, Health Science Centre. 2021;30(4):301-310.

- Pang H, Jia W, Hu Z. Emerging Applications of Metabolomics in Clinical Pharmacology. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2019;106(3):544-556.

- Gonzalez-Covarrubias V, Martínez-Martínez E, Del Bosque-Plata L. The Potential of Metabolomics in Biomedical Applications. Metabolites. 2022;12(2).

- Beger RD. A review of applications of metabolomics in cancer. Metabolites. 2013;3(3):552-574.

- Bourgognon JM, Steinert JR. The metabolome identity: basis for discovery of biomarkers in neurodegeneration. Neural regeneration research. 2019;14(3):387-390.

- Wang JH, Byun J, Pennathur S. Analytical approaches to metabolomics and applications to systems biology. Seminars in nephrology. 2010;30(5):500-511.

- Zhang XW, Li QH, Xu ZD, Dou JJ. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics in health and medical science: a systematic review. RSC advances. 2020;10(6):3092-3104.

- Dettmer K, Aronov PA, Hammock BD. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Mass spectrometry reviews. 2007;26(1):51-78.

- Fiehn O. Metabolomics by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry: Combined Targeted and Untargeted Profiling. Current protocols in molecular biology. 2016;114:30.34.31-30.34.32.

- Kiseleva O, Kurbatov I, Ilgisonis E, Poverennaya E. Defining Blood Plasma and Serum Metabolome by GC-MS. Metabolites. 2021;12(1).

- Mostafa A, Edwards M, Górecki T. Optimization aspects of comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography. Journal of chromatography A. 2012;1255:38-55.

- Allen DR, McWhinney BC. Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry: A Paradigm Shift in Toxicology Screening Applications. The Clinical biochemist Reviews. 2019;40(3):135-146.

- Zhou B, Xiao JF, Tuli L, Ressom HW. LC-MS-based metabolomics. Molecular bioSystems. 2012;8(2):470-481.

- Singh RR, Chao A, Phillips KA, et al. Expanded coverage of non-targeted LC-HRMS using atmospheric pressure chemical ionization: a case study with ENTACT mixtures. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry. 2020;412(20):4931-4939.

- Xiao JF, Zhou B, Ressom HW. Metabolite identification and quantitation in LC-MS/MS-based metabolomics. Trends in analytical chemistry : TRAC. 2012;32:1-14.

- Liu X, Tian X, Qinghong S, et al. Characterization of LC-MS based urine metabolomics in healthy children and adults. PeerJ. 2022;10:e13545.

- Adamski J. Genome-wide association studies with metabolomics. Genome medicine. 2012;4(4):34.

- Nagana Gowda GA, Raftery D. NMR-Based Metabolomics. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2021;1280:19-37.

- Nerli S, McShan AC, Sgourakis NG. Chemical shift-based methods in NMR structure determination. Progress in nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. 2018;106-107:1-25.

- Belhaj MR, Lawler NG, Hoffman NJ. Metabolomics and Lipidomics: Expanding the Molecular Landscape of Exercise Biology. Metabolites. 2021;11(3).

- Crook AA, Powers R. Quantitative NMR-Based Biomedical Metabolomics: Current Status and Applications. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2020;25(21).

- Gowda GA, Zhang S, Gu H, Asiago V, Shanaiah N, Raftery D. Metabolomics-based methods for early disease diagnostics. Expert review of molecular diagnostics. 2008;8(5):617-633.

- Kumar D, Gupta A, Nath K. NMR-based metabolomics of prostate cancer: a protagonist in clinical diagnostics. Expert review of molecular diagnostics. 2016;16(6):651-661.

- Xi B, Gu H, Baniasadi H, Raftery D. Statistical analysis and modeling of mass spectrometry-based metabolomics data. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ). 2014;1198:333-353.

- Saccenti E, Hoefsloot HCJ, Smilde AK, Westerhuis JA, Hendriks MMWB. Reflections on univariate and multivariate analysis of metabolomics data. Metabolomics : Official journal of the Metabolomic Society. 2014;10(3):361-374.

- Pang Z, Chong J, Zhou G, et al. MetaboAnalyst 5.0: narrowing the gap between raw spectra and functional insights. Nucleic acids research. 2021;49(W1):W388-w396.

- Xia J, Psychogios N, Young N, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst: a web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W652-660.

- Gowda GA, Djukovic D. Overview of mass spectrometry-based metabolomics: opportunities and challenges. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ). 2014;1198:3-12.

- Costa C, Maraschin M, Rocha M. An R package for the integrated analysis of metabolomics and spectral data. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine. 2016;129:117-124.

- Sumner LW, Amberg A, Barrett D, et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis Chemical Analysis Working Group (CAWG) Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI). Metabolomics : Official journal of the Metabolomic Society. 2007;3(3):211-221.

- Couch RD, Dailey A, Zaidi F, et al. Alcohol Induced Alterations to the Human Fecal VOC Metabolome. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0119362.

- Mahmud I, Thapaliya M, Boroujerdi A, Chowdhury K. NMR-based metabolomics study of the biochemical relationship between sugarcane callus tissues and their respective nutrient culture media. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry. 2014;406(24):5997-6005.

- Kwak S. Are Only p-Values Less Than 0.05 Significant? A p-Value Greater Than 0.05 Is Also Significant! Journal of lipid and atherosclerosis. 2023;12(2):89-95.

- Tzoulaki I, Ebbels TM, Valdes A, Elliott P, Ioannidis JP. Design and analysis of metabolomics studies in epidemiologic research: a primer on -omic technologies. American journal of epidemiology. 2014;180(2):129-139.

- Worley B, Powers R. Multivariate Analysis in Metabolomics. Current Metabolomics. 2013;1(1):92-107.

- Jolliffe IT, Cadima J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philosophical transactions Series A, Mathematical, physical, and engineering sciences. 2016;374(2065):20150202.

- Worley B, Halouska S, Powers R. Utilities for quantifying separation in PCA/PLS-DA scores plots. Analytical biochemistry. 2013;433(2):102-104.

- Lee LC, Liong CY, Jemain AA. Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) for classification of high-dimensional (HD) data: a review of contemporary practice strategies and knowledge gaps. The Analyst. 2018;143(15):3526-3539.

- Ruiz-Perez D, Guan H, Madhivanan P, Mathee K, Narasimhan G. So you think you can PLS-DA? BMC bioinformatics. 2020;21(Suppl 1):2.

- Tan Y, Shi L, Tong W, Hwang GT, Wang C. Multi-class tumor classification by discriminant partial least squares using microarray gene expression data and assessment of classification models. Computational biology and chemistry. 2004;28(3):235-244.

- Botella C, Ferré J, Boqué R. Classification from microarray data using probabilistic discriminant partial least squares with reject option. Talanta. 2009;80(1):321-328.

- Ruiz-Perez D, Guan H, Madhivanan P, Mathee K, Narasimhan G. So you think you can PLS-DA? BMC bioinformatics. 2020;21(1):2.

- KA LC, Boitard S, Besse P. Sparse PLS discriminant analysis: biologically relevant feature selection and graphical displays for multiclass problems. BMC bioinformatics. 2011;12:253.

- Bastien P, Bertrand F, Meyer N, Maumy-Bertrand M. Deviance residuals-based sparse PLS and sparse kernel PLS regression for censored data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2015;31(3):397-404.

- Chung D, Keles S. Sparse partial least squares classification for high dimensional data. Statistical applications in genetics and molecular biology. 2010;9(1):Article17.

- Lee D, Lee Y, Pawitan Y, Lee W. Sparse partial least-squares regression for high-throughput survival data analysis. Statistics in medicine. 2013;32(30):5340-5352.

- Vajargah KF, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Mehdizadeh-Esfanjani R, Savadi-Oskouei D, Farhoudi M. OPLS statistical model versus linear regression to assess sonographic predictors of stroke prognosis. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2012;8:387-392.

- Shah SH, Kraus WE, Newgard CB. Metabolomic profiling for the identification of novel biomarkers and mechanisms related to common cardiovascular diseases: form and function. Circulation. 2012;126(9):1110-1120.

- Collino S, Martin FP, Rezzi S. Clinical metabolomics paves the way towards future healthcare strategies. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2013;75(3):619-629.

- Buergel T, Steinfeldt J, Ruyoga G, et al. Metabolomic profiles predict individual multidisease outcomes. Nature medicine. 2022;28(11):2309-2320.

- Martínez-Reyes I, Chandel NS. Cancer metabolism: looking forward. Nature reviews Cancer. 2021;21(10):669-680.

- Schmidt DR, Patel R, Kirsch DG, Lewis CA, Vander Heiden MG, Locasale JW. Metabolomics in cancer research and emerging applications in clinical oncology. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021;71(4):333-358.

- Han J, Li Q, Chen Y, Yang Y. Recent Metabolomics Analysis in Tumor Metabolism Reprogramming. Frontiers in molecular biosciences. 2021;8:763902.

- Nascentes Melo LM, Lesner NP, Sabatier M, Ubellacker JM, Tasdogan A. Emerging metabolomic tools to study cancer metastasis. Trends in cancer. 2022;8(12):988-1001.

- An R, Yu H, Wang Y, et al. Integrative analysis of plasma metabolomics and proteomics reveals the metabolic landscape of breast cancer. Cancer & metabolism. 2022;10(1):13.

- Hassan MA, Al-Sakkaf K, Shait Mohammed MR, et al. Integration of Transcriptome and Metabolome Provides Unique Insights to Pathways Associated With Obese Breast Cancer Patients. Frontiers in oncology. 2020;10:804.

- Resurreccion EP, Fong KW. The Integration of Metabolomics with Other Omics: Insights into Understanding Prostate Cancer. Metabolites. 2022;12(6).

- Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends in biochemical sciences. 2016;41(3):211-218.

- DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Daikhin E, et al. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(49):19345-19350.

- Lafita-Navarro MC, Perez-Castro L, Zacharias LG, Barnes S, DeBerardinis RJ, Conacci-Sorrell M. The transcription factors aryl hydrocarbon receptor and MYC cooperate in the regulation of cellular metabolism. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2020;295(35):12398-12407.

- Sica V, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Stoll G, Kroemer G. Oxidative phosphorylation as a potential therapeutic target for cancer therapy. International journal of cancer. 2020;146(1):10-17.

- Ashton TM, McKenna WG, Kunz-Schughart LA, Higgins GS. Oxidative Phosphorylation as an Emerging Target in Cancer Therapy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2018;24(11):2482-2490.

- Giddings EL, Champagne DP, Wu MH, et al. Mitochondrial ATP fuels ABC transporter-mediated drug efflux in cancer chemoresistance. Nature communications. 2021;12(1):2804.

- Caro P, Kishan AU, Norberg E, et al. Metabolic signatures uncover distinct targets in molecular subsets of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer cell. 2012;22(4):547-560.

- Patra KC, Hay N. The pentose phosphate pathway and cancer. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2014;39(8):347-354.

- Li L, Zheng X, Zhou Q, et al. Metabolomics-Based Discovery of Molecular Signatures for Triple Negative Breast Cancer in Asian Female Population. Scientific reports. 2020;10(1):370.

- Lima AR, Pinto J, Bastos ML, Carvalho M, Guedes de Pinho P. NMR-based metabolomics studies of human prostate cancer tissue. Metabolomics : Official journal of the Metabolomic Society. 2018;14(7):88.

- Yu L, Lai Q, Feng Q, Li Y, Feng J, Xu B. Serum Metabolic Profiling Analysis of Chronic Gastritis and Gastric Cancer by Untargeted Metabolomics. Frontiers in oncology. 2021;11:636917.

- Tripathi P, Somashekar BS, Ponnusamy M, et al. HR-MAS NMR tissue metabolomic signatures cross-validated by mass spectrometry distinguish bladder cancer from benign disease. Journal of proteome research. 2013;12(7):3519-3528.

- Zhou H, Li L, Zhao H, et al. A Large-Scale, Multi-Center Urine Biomarkers Identification of Coronary Heart Disease in TCM Syndrome Differentiation. Journal of proteome research. 2019;18(5):1994-2003.

- Ullah E, El-Menyar A, Kunji K, et al. METABOLOMICS REVEALS PERTURBATIONS IN ARGININE-NO METABOLISM, PURINE BIOSYNTHESIS AND CELLULAR ENERGY CHARGE IN PATIENTS WITH CORONARY HEART DISEASE. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021;77:22.

- Kordalewska M, Markuszewski MJ. Metabolomics in cardiovascular diseases. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis. 2015;113:121-136.

- Senn T, Hazen SL, Tang WH. Translating metabolomics to cardiovascular biomarkers. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2012;55(1):70-76.

- Li B, Gao G, Zhang W, et al. Metabolomics analysis reveals an effect of homocysteine on arachidonic acid and linoleic acid metabolism pathway. Molecular medicine reports. 2018;17(5):6261-6268.

- Stratmann B, Richter K, Wang R, et al. Metabolomic Signature of Coronary Artery Disease in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. International journal of endocrinology. 2017;2017:7938216.

- Rangel-Huerta OD, Pastor-Villaescusa B, Gil A. Are we close to defining a metabolomic signature of human obesity? A systematic review of metabolomics studies. Metabolomics : Official journal of the Metabolomic Society. 2019;15(6):93.

- Taghizadeh H, Emamgholipour S, Hosseinkhani S, et al. The association between acylcarnitine and amino acids profile and metabolic syndrome and its components in Iranian adults: Data from STEPs 2016. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2023;14:1058952.

- Gupta S, Sharma U. Metabolomics of neurological disorders in India. Analytical Science Advances. 2021;2(11-12):594-610.

- Quintero ME, Pontes JGM, Tasic L. Metabolomics in degenerative brain diseases. Brain research. 2021;1773:147704.

- Roche S, Gabelle A, Lehmann S. Clinical proteomics of the cerebrospinal fluid: Towards the discovery of new biomarkers. Proteomics Clinical applications. 2008;2(3):428-436.

- Huo Z, Yu L, Yang J, Zhu Y, Bennett DA, Zhao J. Brain and blood metabolome for Alzheimer’s dementia: findings from a targeted metabolomics analysis. Neurobiology of aging. 2020;86:123-133.

- Haass C, Kaether C, Thinakaran G, Sisodia S. Trafficking and proteolytic processing of APP. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012;2(5):a006270.

- Liu CC, Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nature reviews Neurology. 2013;9(2):106-118.

- Burke SL, Maramaldi P, Cadet T, Kukull W. Associations between depression, sleep disturbance, and apolipoprotein E in the development of Alzheimer’s disease: dementia. International psychogeriatrics. 2016;28(9):1409-1424.

- Klosinski LP, Yao J, Yin F, et al. White Matter Lipids As a Ketogenic Fuel Supply in Aging Female Brain: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(12):1888-1904.

- Wilkins JM, Trushina E. Application of Metabolomics in Alzheimer’s Disease. Frontiers in neurology. 2017;8:719.

- Horgusluoglu E, Neff R, Song WM, et al. Integrative metabolomics-genomics approach reveals key metabolic pathways and regulators of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2022;18(6):1260-1278.

- Liang Q, Liu H, Zhang T, Jiang Y, Xing H, Zhang A-h. Metabolomics-based screening of salivary biomarkers for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. RSC advances. 2015;5(116):96074-96079.

- Batra R, Arnold M, Wörheide MA, et al. The landscape of metabolic brain alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2022.

- Varma VR, Oommen AM, Varma S, et al. Brain and blood metabolite signatures of pathology and progression in Alzheimer disease: A targeted metabolomics study. PLoS medicine. 2018;15(1):e1002482.

- Fiehn O. Metabolomics–the link between genotypes and phenotypes. Plant molecular biology. 2002;48(1-2):155-171.

- Aarsland D, Batzu L, Halliday GM, et al. Parkinson disease-associated cognitive impairment. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2021;7(1):47.

- Shao Y, Le W. Recent advances and perspectives of metabolomics-based investigations in Parkinson’s disease. Molecular neurodegeneration. 2019;14(1):3.

- LeWitt PA, Li J, Lu M, Guo L, Auinger P. Metabolomic biomarkers as strong correlates of Parkinson disease progression. Neurology. 2017;88(9):862-869.

- Luan H, Liu LF, Tang Z, et al. Comprehensive urinary metabolomic profiling and identification of potential noninvasive marker for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Scientific reports. 2015;5:13888.

- Trezzi JP, Galozzi S, Jaeger C, et al. Distinct metabolomic signature in cerebrospinal fluid in early parkinson’s disease. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2017;32(10):1401-1408.

- Lewitt PA, Li J, Wu KH, Lu M. Diagnostic metabolomic profiling of Parkinson’s disease biospecimens. Neurobiology of disease. 2023;177:105962.

- Roede JR, Uppal K, Park Y, et al. Serum metabolomics of slow vs. rapid motor progression Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77629.

- Solana-Manrique C, Sanz FJ, Torregrosa I, et al. Metabolic Alterations in a Drosophila Model of Parkinson’s Disease Based on DJ-1 Deficiency. Cells. 2022;11(3).

- Scholefield M, Church SJ, Taylor G, Knight D, Unwin RD, Cooper GJS. Multi-regional alterations in glucose and purine metabolic pathways in the Parkinson’s disease dementia brain. NPJ Parkinson’s disease. 2023;9(1):66.

- Dunn L, Allen GF, Mamais A, et al. Dysregulation of glucose metabolism is an early event in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of aging. 2014;35(5):1111-1115.

- Anandhan A, Jacome MS, Lei S, et al. Metabolic Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease: Bioenergetics, Redox Homeostasis and Central Carbon Metabolism. Brain research bulletin. 2017;133:12-30.

- Dorcely B, Katz K, Jagannathan R, et al. Novel biomarkers for prediabetes, diabetes, and associated complications. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity : targets and therapy. 2017;10:345-361.

- Jin Q, Ma RCW. Metabolomics in Diabetes and Diabetic Complications: Insights from Epidemiological Studies. Cells. 2021;10(11).

- Pallares-Méndez R, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Cruz-Bautista I, Del Bosque-Plata L. Metabolomics in diabetes, a review. Annals of medicine. 2016;48(1-2):89-102.