Microbiological Techniques for Optimal Probiotic Blends

Microbiological Techniques to Study Undue Strain Dominance Among Probiotic Bacteria in Order to Develop Compatible Multiple Mixed Probiotic Cultures to Prevent or Treat Diseases

Dr. Malireddy S. Reddy, BVSc (DVM)., MS., Ph.D.1

- International Media and Cultures, Inc. [IMAC], American Dairy and Food Consulting Labs, Inc. [ADFAC Labs, Inc], Denver, Colorado, USA.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 January 2025

CITATION: Reddy, MS., 2025. Microbiological Techniques to Study Undue Strain Dominance Among Probiotic Bacteria In Order to Develop Compatible Multiple Mixed Probiotic Cultures to Prevent or Treat Diseases. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(1). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6201

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6201

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

In this investigation, suitable microbiological techniques and procedures were developed to study associative growth relationships among various probiotic cultures in order to maintain their intended component balance, without any one particular probiotic culture dominating others in a mixed culture by screening them ahead of time using several differential and selective bacteriological media to arrive at a highly-functional therapeutic pharmaceutical mixed probiotic culture. A simulated procedure has been developed mimicking the gradual pH transition of the human Gastro Intestinal tract starting from duodenum to the distal end of the colon. This procedure was developed to study the strain dominance phenomena of when mixed probiotic cultures are grown in a growth medium and sub-cultured through several transfers. The selection criteria applied is if a mixed probiotic culture that can maintain all its individual components through several transfers in the growth medium should be the choice of using it as a functional therapeutic probiotic blend. The results of the investigation proved that undue dominance does exist among strains of probiotics, which belongs not only to different genera, but also among members of the same species when they are grown together. The techniques outlined in this investigation can and has been applied clinically to study the composition of fecal Microbiota, to assess the GI tract health of the human being, and also to develop custom blends of proprietary pharmaceutically-superior therapeutic multiple mixed probiotic cultures to treat Dysbiosis, with choice than chance. The results also proved dominance among the members of mesophilic probiotic species of Lactococcus is more prevalent than thermophilic probiotics belonging to the genus Streptococcus and Lactobacillus. It illustrates that multiple mixed strain probiotic cultures have to be manufactured – for therapeutic purpose – only after determining their associative growth relationships in order to eliminate undue dominance of one particular probiotic culture over another in a mixed culture, and also subsequently in the GI tract of humans after ingestion. Using the microbiological techniques and procedures developed in this investigation, the compositions of novel mixed-strain probiotic cultures outlined in US Patent 11,077,052 B1 have been evaluated and proven that probiotic components used were compatible with no undue domination, thus successfully curing viral and bacterial infections through optimized Microbiota.

Keywords:

Reddy’s Differential Agars; Lee’s Agar: Selective Agars; Component Balance; Dr. M.S. Reddy’s multiple mixed strain probiotic therapy; US patent # 11,077,052 B1; Lactococcus lactis var. lactis; Lactococcus lactis var. cremoris; Lactococcus lactis var. lactis ssp. diacetylactis; Streptococcus thermophilus; Lactobacillus bulgaricus; Propionibacterium; Enterococci; Saccharomyces boulardi; Probiotics; miRNAs; memiRNAs.

Introduction:

Probiotics confer health to human beings by orchestrating the immune system and also through the prevention of pathogenic bacterial invasion in the GI tract and respiratory system. Therapeutic strains of probiotic microorganisms belong to several genera and species. Each probiotic strain exerts its own therapeutic property through the production of specific molecules, called immunomodulins. Thus, multiple mixed-strain probiotics are preferable to maximize their therapeutic potential to improve human health. Unfortunately, in a mixed culture some strains of probiotics tend to dominate over others, resulting in obviating the vital function of the mixed culture. In this investigation, suitable microbiological techniques were developed to study the associative growth relationships among strains of probiotics in order to maintain their intended component balance, without any strain domination, by screening them ahead of time using several differential and selective agars to arrive at the highly functional therapeutic pharmaceutical mixed probiotic cultures.

Probiotics are gaining significant importance in the health, nutrition and the medical fields due to their proven all-natural, exceptional and therapeutic functions. They are well accepted worldwide by FAO and WHO, and several medical institutions as one of the best alternatives for antibiotics, to eliminate antibiotic resistant superbugs, which are killing millions of people worldwide. The latest definition of probiotics was defined and established in the year 2001, by the United Nations Food And Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) in collaboration with the Canadian Research And Development Center For Probiotics, which is: Probiotics are any live micro-organisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on host. In this connection, using probiotics as nutritional supplements or probiotic therapy comes under the heading of “Biologically Based Medical Practices “according to the NCCAM (National Center For Complementary And Alternative Medicine), which is a division of NIH (National Institute Of Health), which ultimately governs various categories of the Complementary And Alternative Medicine.

To give a brief background of probiotics, it is worthwhile to look into their genesis. Their genesis goes back to over 5000 years or perhaps even longer. According to the Vedic scripts of India, Lord Krishna, a Hindu deity, was the original instigator of consuming fermented milk products perhaps prepared by natural undefined microorganisms present in milk as natural inhabitants. Even to date, this practice of consuming fermented dairy products made at home using their own family maintained undefined probiotic culture, on a daily basis, continued without interruption in every Indian household.

In the year 1908, the Nobel Laureate Dr. Elie Metchnikoff, professor at the Pasteur Institute of Paris, openly announced that the longevity of human beings, with good health, can be improved thru daily ingestion of Lactic acid bacteria (specifically the bacteria belong to genus Lactobacillus), through prevention of putrification in the human Gastrointestinal tract. Until the late years of the 1960s the concept of probiotics, improving human health, was not well accepted and thus was not taken seriously in the western world. During WW II approximately around the year 1945, the Nobel Laureate Dr. Alexander Flemming’s discovery of antibiotic penicillin was introduced worldwide as an aid to suppress or inhibit pathogenic bacteria causing sepsis. Since then, several versions of antibiotics were developed by the pharmaceutical industry to kill variety of the mutated pathogenic bacteria. Due to unscrupulous use of a variety of antibiotics, as of today, we have a serious life threatening problem due to mutated multiple antibiotic resistant bacteria, super bugs, such as C.diff and MRSA etc. causing deaths of millions of people. Consequently, the entire world including WHO is looking into all natural probiotic therapy, as a replacement to antibiotic therapy.

To enlighten this little bit further, it is interesting to note that human Gastrointestinal tract harbors over or close to 100 trillion micro-organisms, represented by close to 1000 genera and species. The total number of Prokaryotic bacteria in GI tract is termed Microbiota. Whereas the total number of genes in the Microbiota is called Microbiome. The total number of human Eukaryotic cells in human beings is roughly ten trillion. Thus, the number of Prokaryotic micro-organisms in humans is ten times more than the Eukaryotic human cells. Thus, in terms of gene pool, the total Microbiome of GI tract far exceeds the human microbiome. It signifies that for over billions of years this symbiotic association between beneficial micro-organisms and humans has been established. Of course, these micro-organisms are also associated with the tissues of the respiratory system, but their numbers are far less than the ones encountered in GI tract. Out of the 100 trillion micro-organisms, roughly 20% of them are probiotics. Any major disturbance in the composition of the Microbiota results in Dysbiosis, which will ultimately prone human beings to several diseases involving various organs causing cardiac diseases and cancers etc. Unscrupulous use of antibiotics, medications, preservatives in foods, excess consumption of alcohol, Stress, and irregular lifestyle are some of the causes for the dysbiosis or altered composition of Microbiota in a negative way.

Due to extensive research by various bacteriologists, scientists, and medical professionals, it is proven that probiotics can cure various melodies. They can reduce GI tract inflammations, Allergies, Cholesterol, Pathogenic bacterial infections, certain Cancers, Lactose intolerance, Obesity, Retrovirus Diarrhea, Gastric ulcers caused by Helicobacter pylori etc., through competitive inhibition of pathogenic bacteria and viruses. In addition to the above listed therapeutic functions, the probiotic’s vital function is to orchestrate the immune system through immunomodulation. An extensive study by Reddy proved that Multiple Mixed Strain Probiotics along with their immunomodulins can prevent or cure Hospital associated infections (Nosocomial Infections) due to C. diff (Clostridium difficile) and MRSA (Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus) and several other antibiotic resistant pathogenic bacteria. He has also discovered and proved that Dr. M. S. Reddy’s Multiple Mixed Strain Probiotic therapy can be used as an adjuvant therapy along with the standard cancer therapies to cure cancer with least or no relapse. His latest novel invention of preventing or treating COVID -19 pandemic, (caused due to Corona viral (SARS-CoV-2) infection), through use of Multiple Mixed Strain Probiotics along with their immunomodulins is the first and foremost pioneering invention in the world, attested by the grant of US patent # 11,077,052 B1 for its novelty.

Although several inventions proved the validity of probiotics as therapeutic agents, the selection of probiotic strains to be used in the formulations needs significant improvement. The lack of such investigations until now is partly due to insufficient advancement in the arena of microbiology, specifically relating to serious attempts to study the associative growth relationships among strains of probiotic bacteria. Contrary to thinking of people, there are hundreds and hundreds of probiotic microorganisms with different therapeutic properties. Since several genera and species of bacteria are categorized under probiotics, one has to study the compatibility among these strains before blending them into therapeutic mixed culture formulation. In order to achieve this, the intended probiotic bacterial strains have to be grown together in various combinations, to eliminate the unforeseen strain domination. Since each individual probiotic strain (even though they belong to same genera and species) has its own unique therapeutic properties, blending of several of these strains at random, without checking their comparability, violates the function and merit of the mixed culture concept. The concept of mixing various strains of probiotics belonging to several genera and species is to derive maximum therapeutic benefit of each and every component in such mixed culture. Unfortunately, if strain dominance occurs among members of the probiotics, the purpose is defeated. In this connection, I would like to enlighten the meaning of probiotic strain dominance, and also the difference between differential agar vs. selective agar, since these terminologies are extensively used in this investigation.

PROBIOTIC STRAIN DOMINANCE

When two or more bacterial species or strains belonging to different genera or same genera are grown together, one strain tends to dominate the other strain by suppressing their growth due to several factors, such as nutritional competency, rate of acid production, production of antimicrobial components etc. The latest pioneering breakthrough discovery published in the Medical Research Archives of the European Society of Medicine is also pointing out the significant role of prokaryotic produced micro RNAs (memiRNAs), which are dictating the superiority of one probiotic culture over others. This current investigation is undertaken to study associative growth relationship among strains of probiotics elected to be used in a mixed probiotic therapeutic pharmaceutical blend using the direct plating techniques with the aid of differential and selective media. Such a study will be extremely useful to mix the compatible probiotic strains only, with no strain dominance, in a mixed therapeutic formulation to improve its pharmacological effect on curing several infections and diseases with accuracy.

DIFFERENTIAL MEDIA VS. SELECTIVE MEDIA

In bacteriology, it is a common practice to identify the genus and species of the bacteria using various biochemical and serological tests and sometimes using specific bacteriophages etc., which is tedious, labor intense and time consuming. A differential media is a bacteriological media which can differentiate directly several unrelated members on the same agar plate, without having to conduct several biochemical tests to identify each colony. Using the differential agar, one can study the phenomena of strain dominance among probiotic bacteria when two or more of them are grown together. Whereas selective media is specifically designed to enumerate only particular genera of probiotic bacteria through the use of selective inhibitory agent(s) in the bacteriological growth media. However, the selective agar cannot distinguish species belonging to the same genera. Contrary to differential media, a selective media only allows growth of particular probiotic bacteria by inhibiting other microorganisms. As an example, Sodium Lactate agar only allows the growth of species belonging to genus Propionibacterium. The central idea of this research project is to use several differential agar media and selective media and suitable methodologies and techniques to study the component balance stability to formulate a stable multiple mixed-strain probiotic therapeutic blend, in which no one probiotic culture can dominate another, since each culture has its own therapeutic benefit on its host to ameliorate the infections or diseases.

In order to study the phenomena of dominance among probiotic cultures, we have elected to use 12% solids reconstituted nonfat dry milk as a growth medium in order to simulate the growth or survival patterns in the human gastrointestinal tract. Most of the probiotic strains are acid producers and they can tolerate acidic conditions in the stomach and further alkalinity in the Duodenum, followed by slightly lower pH conditions in the Jejunum, Ileum, and Colon. Our simulated design is such that the probiotic bacteria do not grow much for the first few hours (lag phase) just like in the human stomach. As long as probiotic bacteria are not multiplying or growing, they will not get hurt even under such acidic conditions in the stomach. The next step of their growth simulates the condition in the rest of the GI tract in terms of pH and acidity. This may not be totally accurate, but it is an approximate aid to simulate the conditions of GI tract, to study the strain dominance among probiotics under different conditions encountered in GI tract. The gradual drop in pH due to growth of probiotic bacteria in high solids milk media is comparable to pH shifts in the human GI tract, starting from the duodenum to the distal end of the colon.

Thus, the purpose of this investigation is to develop applicable microbiological techniques and procedures, such as variety of specialized differential media and selective media to study the associative growth relationships among various probiotic cultures, in an attempt to eliminate dominance of one probiotic microorganism over others in order to arrive at the most suitable compatible pharmaceutical therapeutic formulations. These formulations have been used successfully to treat several diseases, including viral infections (both RNA/ DNA viruses), including but not limited to COVID-19, influenza, Ebola, Bird Flu (H5N1), Hospital Associated Multiple Antibiotic Resistant superbugs – C.diff and MRSA, etc., long COVID and certain autoimmune diseases.

Materials and Methods:

EXPERIMENT-1:

In this experiment, the component balance among two probiotic species belonging to genus Lactococcus, upon growth as a mixed culture, was determined by using a differential agar. The composition and preparation of differential agar media, which can differentiate the probiotic Lactococcus lactis var. lactis and probiotic Lactococcus lactis var. cremoris is per the published information by Reddy et.al. Hereafter, for the sake of simplicity, this medium is referred to as Reddy’s double differential agar. Single strains of Lactococcus lactis var. lactis and Lactococcus lactis var. cremoris were grown separately in sterile reconstituted 12% solids non-fat dry milk, by incubating at 32 C for 16 hours, which were used as seed or mother cultures. Thus, the liquid cultures ended up with their own immunomodulins or growth end products. The total bacterial counts were determined using enriched tryptic soy agar. Also, single probiotic cultures were surface-plated on Reddy’s double differential agar and incubated in a CO2 incubator at 32 C for 48 hours. Alternatively, a candle oats jar can also be used in place of CO2 incubator. Lactococcus lactis var. lactis strains (hereafter abbreviated as L. lactis var. lactis) should yield white colonies on this agar. Whereas the Lactococcus lactis var. cremoris culture (hereafter abbreviated as L. lactis var. cremoris) will appear yellow due to acid production on the differential agar. After affirming these results, we have studied the associative growth relationships when such probiotic cultures were grown together. One ml. of each of L. lactis var. lactis (SL-1) and L. lactis var. cremoris (SC-1) were inoculated into 12 % solids sterile reconstituted non-fat dry milk. The bottles, along with controls, were incubated at 32 C for 16 hours. This is reported as first transfer. At the end of the incubation, the culture was surface plated on the differential agar and incubated in CO2 incubator for 48 hours. The yellow and white colonies were counted to check for any domination of one probiotic culture over the other. The liquid mixed culture (first transfer) was transferred again into fresh 12% solids non-fat dry milk and incubated at 32 C for 16 hours (this is named as second transfer) and the differential counts were determined using the same procedure as outlined earlier. The second transfer culture was again transferred (third transfer) and the probiotic differential counts were determined using the same Reddy’s double differential agar. Similarly, various combinations of probiotic strains of L. lactis var. lactis (SL-2) and L. lactis var. cremoris (SC-2) were studied to check for the compatibility.

EXPERIMENT-2:

This experiment was designed to study the associative growth relationships among three different probiotic bacteria belong to same genera but different species, when grown together using Reddy’s triple differential agar, which can distinguish 3 different species on a single agar. The three probiotic bacterial species checked were L. lactis var. lactis, L. lactis var. cremoris, and L. lactis var. lactis ssp. diacetylactis. Reddy’s differential agar was made using the procedure outlined in the publication, with slight modifications. These modifications include mixing all the ingredients at one time rather than making them in two different steps. Yet the indicator bromocresol purple and the sterile reconstituted non-fat dry milk were added to the melted sterile agar just before pouring into chilled petri plate. The plates were dried overnight and the appropriate dilution (10-7) of the culture was surface plated. The plates were incubated in a CO2 incubator for 2-6 days. Alternatively candle oats jar can also be used in place of CO2 incubator. These aforementioned three cultures were cultured separately using sterile 12% solids reconstituted non-fat dry milk. The single strains were also plated on the agar to check for their identity. L. lactis var. cremoris colonies should appear yellow, L. lactis var. lactis should appear as large white colonies, and L. lactis var. lactis ssp. diacetylactis appear as white colonies with distinct clear zones around. Equal amounts of three seed probiotic cultures (1% each) were inoculated into a similar medium as outlined in experiment 1 and incubated at 32 C for 16 hours (this is named first transfer). At the end of 16 hours, the mixed probiotic culture was streaked on the differential agar to determine the count of each strain using the procedure outlined by Reddy et.al. The first transfer culture was inoculated into sterile reconstituted non-fat dry milk and incubated using similar incubation temperature and length of incubation. This is considered as a second transfer. Similarly, a third transfer was also conducted. All the first, second and third transfer cultures were plated on Reddy’s triple differential agar to determine the counts of each individual probiotic culture. The identity of the colonies was further confirmed by using Reddy’s triple differential broth. In this differential broth, L. lactis var. cremoris colony inoculated into broth turns the entire broth color yellow upon growth. Whereas, L. lactis var. lactis turns the broth color purple, and L. lactis var. lactis ssp. diacetylactis turns the broth color purple with production of gas, which is collected in the Durham tube. Two different culture combinations were studied for the compatibility in this example. They are: First Combination – L. lactis (SL-1) – L. cremoris (SC-1) – L. diacetylactis (SD-1) Second Combination: L. lactis (SL-2) – L. cremoris (SC-2) – L. diacetylactis (SD-2)

EXPERIMENT-3:

This experiment was designed to check for the compatibility among probiotic cultures belonging to different genera and species such as Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus. The differential agar used here is Lee’s agar which can differentiate between S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus bacteria on the basis of the color and size of the colonies, wherein S. thermophilus appear as large yellow colonies, and L. bulgaricus appear as small pink colonies upon plating and incubation. Since these probiotic strains are widely used in mixed cultures, we thought we would grow them in the milk together (three transfers as outlined in experiment 1 and 2) to see if they are compatible. Equal amounts of (1% each) milk grown probiotic cultures of S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus were inoculated into sterile 12% solids reconstituted non-fat dry milk and incubated at 37 C for 8 hours (first transfer). At the end of incubation, the culture was further inoculated into fresh sterile 12% solids of reconstituted non-fat dry milk and incubated at 37 C for 8 hours (second transfer). Both the transfer culture 1, 2 and culture 3 (similar procedure was adopted to arrive at third transfer culture) were surface plated on to Lee’s differential agar and the plates were incubated for 48-72 hours and the counts of each strain were determined. In addition, the microscopy was conducted to check for different morphologies and ratios of these probiotic cultures, after they were grown together. The procedure of making Lee’s agar and plating techniques were followed as per the published information. In this example, two different culture combinations were studied to check for their compatibility. They are: First Combination – S. thermophilus (ST-A) – L. bulgaricus (LB-A) Second Combination: S. thermophilus (ST-B) – L. bulgaricus (LB-B)

EXPERIMENT-4:

The GRAS (Generally Regarded As Safe) probiotic cultures also include different additional microorganism belonging to various genus and species, other than the ones used in experiments 1, 2, and 3. We have elected to use the members of genus Enterococcus (Enterococcus faecium), Propionibacterium (Propionibacterium shermanii), and Yeast (Saccharomyces boulardi), etc. These probiotic cultures were blended at equal proportions and one ml. of the mixed culture was inoculated into sterile 12 % solids of non-fat dry milk and incubated at 32 C for 24, 48 and 72 hours. At the end of the specific incubation period, the samples were plated (pour plating) on KF streptococcus agar, sodium lactate agar, and potato dextrose agar. The composition and preparation of media was according to the procedures outlined in the Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Foods (of the American Public Health Association). KF streptococcus agar was used to enumerate Enterococcus faecium by incubating pour plates at 37C for 48 hours. Whereas sodium Lactate agar was used to enumerate Propionibacterium species, by incubating at 32 C for 6 days using candle oats jar or carbon dioxide incubator. Finally, to enumerate Saccharomyces boulardi, acidified potato dextrose agar was used, and the incubation temperature was 21 C for a period of 4 days. These aforementioned bacteriological media are selected agars designed to isolate a particular group of members belonging to one genus only, but cannot be applicable to differentiate species present in the same genus.

EXPERIMENT-5:

This experimental design is the same as Experiment 4, except in addition to the above specified probiotic organisms listed in Experiment-4, L. lactis var. lactis, L. lactis var. cremoris, L. lactis var. lactis ssp. diacetylactis, S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus were inoculated and the mixed culture was incubated at 32 C for 72 hours. The mixed culture, after growth at specified intervals, was plated on various selective agars as listed in Experiment-4. In addition, the culture was also plated on Lac +ve and Lac-ve differential agar and incubated for 48 hours at 32 C in CO2 incubator to differentiate between Lac+ve acid producers and Lac-ve (nonacid producers) cultures in the mixed culture. The composition of Lac+ve and Lac-ve differential agar is as follows: Tryptone (0.5%), Yeast Extract (0.5%), Di Potassium Hydrogen Phosphate (0.1%), Casamino acids (0.25%), Calcium Carbonate (0.3%), Carboxy Methyl Cellulose (0.6%), Lactose (0.25%)a, Bromo Cresol Purple (BCP) (0.002%)b, Agar (0.15%), Distilled water (100 ml.). a: 2 ml. of 10% filter sterilized lactose added at the time of pouring plates. b: 2 ml. of 0.2% sterile BCP solution added to every 100 ml sterile agar at the time of pouring plates. The mixed probiotic culture at specified intervals of growth was surface-plated on dried agar plates of Lac+ve and Lac-ve medium, and incubated at 32 C for 48 hours in CO2 incubator.

Results:

EXPERIMENT-1:

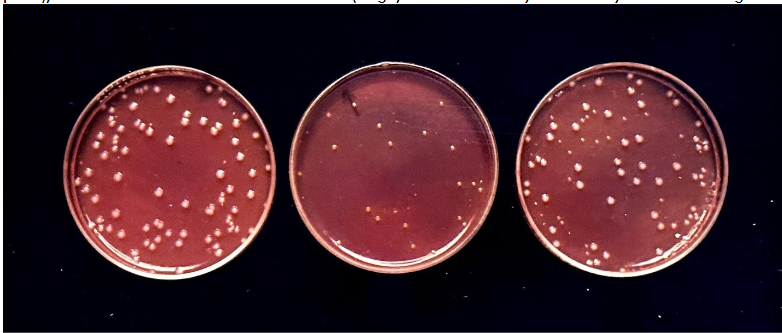

The results of this experiment are presented in Table 1 and the pictorial presentation is reflected in Figure 1. Figure 1 shows the appearance of the colonies of probiotic strains of L. lactis var. cremoris and L. lactis var. lactis separately and together on the Reddy’s double differential agar. For the sake of simplicity hereafter L. lactis var. lactis and L. lactis var. cremoris will be referred to as L. lactis and L. cremoris correspondingly. The L. cremoris colonies appeared yellow due to lack of enzymatic systems to hydrolyze L-arginine hydrochloride, whereas L. lactis colonies appeared white because of liberation of ammonia due to hydrolyses of L- arginine hydrochloride thus shifting of pH towards alkalinity of the colony. Figure 1 also shows the appearance of both yellow and white colonies together in one plate. It confirms that the probiotic strains used in this study can be successfully identified and validated, to successfully study the associative growth relationships among these bacteria when they are grown together. The results of the associative growth relationships of the mixed probiotic L. cremoris and L. lactis, determined using Reddy’s double differential agar, are presented in Table 1. The results distinctly proved that the combination of L. lactis-1 (SL-1) and L. cremoris-1 (SC-1) was highly compatible without any strain domination, even after three successive transfers of growth in the reconstituted non-fat dry milk. The net effect, such probiotic culture combination can be used to successfully manufacture mixed probiotic therapeutic pharmaceutical composition. Conversely, the results presented in Table 1, distinctly proved that in Combination-2 with the inclusion of L. lactis (strain SL-2) and L. cremoris (strain SC-2) severe strain domination of one probiotic culture over the other was observed. L. cremoris strain SC-2 dominated totally by suppressing the growth of L. Lactis SL-2, even after the first transfer. Such non-compatible probiotic cultures should be eliminated in the pharmaceutical preparation of the mixed probiotic culture, to be used as a therapeutic ingredient.

| No. of Transfers | Combination-1 of L. lactis var. lactis (SL-1) | Combination-2 of L. lactis var. lactis (SL-2) and L. lactis var. cremoris (SC-2) | L. lactis var. lactis (SL-1) | L. lactis var. cremoris (SC-1) | L. lactis var. lactis (SL-2) | L. lactis var. cremoris (SC-2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 150 x 107 | ND | at 107 | 150 x 107 | ||

| Second | 200 x 107 | ND | at 107 | 170 x 107 | ||

| Third | 180 x 107 | ND | at 107 | 130 x 107 |

EXPERIMENT-2

In this experiment the compatibility among probiotics of three different species belonging to genus Lactococcus were studied using Reddy’s triple differential agar. The probiotic cultures used in this experiment were L. lactis var. lactis (herein referred to as L. lactis); L. lactis var. cremoris (herein referred to as L. cremoris), and L. lactis var. lactis ssp. diacetylactis (herein referred to as L. diacetylactis). The single strains of these probiotics were plated on the differential agar, to check for their identification in terms of the color (yellow or white) and clear zoning around the colonies. This is presented in Figure-2. Figure-2 shows that the L. cremoris culture (SC-1) showed distinct yellow colonies due to its biochemical character of being L- arginine negative. The L. lactis culture (SL-1) appeared as a white colony because of the ammonia liberation due to its inherent capacity to hydrolyze L- arginine. The L. diacetylactis appeared as a white colony with distinct clear zoning around each colony due to its dual ability to hydrolyze L-arginine and also to utilize calcium citrate as a source of carbon. When calcium citrate was utilized, the opaque nature of the compound turned into a clear zone, around the L. diacetylactis colonies.

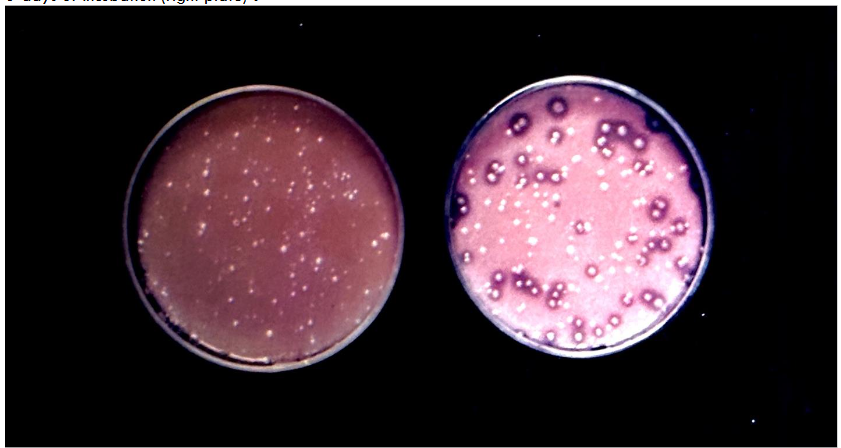

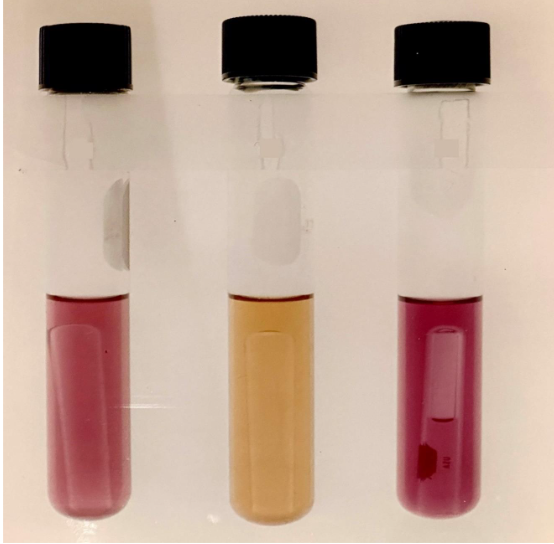

Figure 3 shows (left side) the colony color identification after 48 hours incubation, wherein L. cremoris appeared as yellow colony, and both L. lactis and L. diacetylactis appeared white. The second plate (right side) in Figure 3 shows the differentiation of L. diacetylactis with distinct clear zone around the white colony in comparison to L. lactis after 6 days of incubation. The cultures plated using grown mixed culture on the triple differential agar was further verified by picking and growing the individual colonies using differential broth. The identification of the species is shown in figure-4. The test tube on the left side, which is purple is L. lactis, the middle test tube, which is yellow is L. cremoris, the tube on the right side, which is purple and has gas in Durham tube is L. diacetylactis. Only after establishing the differentiation patterns of probiotic cultures belonging to different Lactococcus species, we have proceeded to conduct the experiments to determine the compatibility among these strains when they are grown together, to arrive at a suitable combination to manufacture therapeutic pharmaceutical probiotic blend. The results are presented in Table-2. The mixed Combination-1, of having probiotic components L. lactis SL-1, L. cremoris SC-1, and L. diacetylactis SD-1 exhibited significant domination by probiotics L. diacetylactis and L. lactis over L. cremoris, indicating that such culture combination is incompatible to be used as a mixed probiotic to manufacture nutraceutical or pharmaceutical probiotic blend to be used as therapeutic formula. The mixed probiotic Combination-2 with the components L. lactis SL-2, L. cremoris SC-2, L. diacetylactis SD-2 did not exhibit any strain domination even upon growing them together through three transfers in the reconstituted non-fat dry milk. Thus, such compatible probiotic strains can be successfully used to formulate mixed probiotic pharmaceutical preparations.

| No. of Transfers | Combination-1 of L. lactis var. lactis (SL-1), L. lactis var. cremoris (SC-1) and L. lactis var. lactis ssp. diacetylactis (SD-1) | Combination-2 of L. lactis var. lactis (SL-2), L. lactis var. cremoris (SC-2) and L. lactis var. lactis ssp. diacetylactis (SD-2) | L. lactis var. lactis (SL-1) | L. lactis var. cremoris (SC-1) | L. lactis var. lactis ssp. diacetylactis (SD-1) | L. lactis var. lactis (SL-2) | L. lactis var. cremoris (SC-2) | L. lactis var. lactis ssp. diacetylactis (SD-2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 150 x 107 | 80 x 107 | 120 x 107 | 55 x 107 | 140 x 107 | |||

| Second | 120 x 107 | ND | 180 x 107 | 40 x 107 | 180 x 107 | |||

| Third | 85 x 107 | ND | 170 x 107 | 30 x 107 | 190 x 107 |

EXPERIMENT-3

Although we have not included the photograph showing the differentiation of bacteria, S. thermophilus strains appeared as large yellow colonies because they are sucrose positive, whereas L. bulgaricus strains appeared small and pink due to lack of their ability to utilize sucrose. Both the combinations of different S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus strains exhibited good compatibility after repeatedly growing them through three successive transfers in the reconstituted non-fat dry milk. The results are presented in Table 3. Combination-1 with strains ST-A and LB-A exhibited better associative growth relationship in terms of maintaining the component balance. Whereas Combination-2, with strains ST-B and LB-B, did not perform as good as combination one, in terms of maintaining the component balance. Consequently, the preference would be to pick Combination-1 over Combination-2, to fabricate a mixed probiotic pharmaceutical therapeutic preparation. The strain domination noticed in the probiotic-mixed culture of S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus is not as noticeable as the probiotic members of Lactococcus group, as presented in Tables 1 and 2. Perhaps it is due to the good symbiotic relationship between the probiotic members of the genus streptococcus and lactobacillus, as opposed to probiotic strains among the species of the genus Lactococcus.

| No. of Transfers | Combination-1 of S. thermophilus (ST-A) and L. bulgaricus (LB-A) | Combination-2 of S. thermophilus (ST-B) and L. bulgaricus (LB-B) | Lactobacillus bulgaricus | Streptococcus thermophilus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 50 x 107 | 30 at 107 | 35 x 107 | 100 x 107 |

| Second | 35 x 107 | 80 at 107 | 80 x 107 | 60 x 107 |

| Third | 80 x 107 | 130 at 107 | 90 x 107 | 10 x 107 |

EXPERIMENT-4

In this experiment we have included several probiotic bacteria belonging to genus Enterococcus, Propionibacterium, and probiotic yeast culture Saccharomyces, since they are also essential ingredients of the human microbiota. The Propionibacterium species are predominantly responsible for short-chain fatty acids, which are essential for the growth and maintenance of other beneficial members of the human Microbiota. Similarly, probiotic species belonging to the genus Enterococcus and Saccharomyces have significant therapeutic effects on guarding and improving intestinal health. The results of this experiment are presented in Table-4. Although Propionibacterium counts were not detected at 24 hours incubation, they did grow after 48-72 hours of incubation. This delay in the growth of the species of the genus Propionibacterium perhaps was due to their longer lag phase. Overall, none of these probiotic bacterial and yeast cultures exhibited any strain domination over other, when grown together, determined using selective agars for enumeration. Such cultures can be used safely to formulate pharmacologically sound probiotic therapeutic blends to be used as nutraceuticals and/or dietary supplements and/or pharmaceutical preparations.

| Genera and Species | Selective medium used | Bacterial Counts at Different Lengths of Incubation (in HRS) |

|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecium | KF Streptococcus Agar | 100 x 107 |

| Propionibacterium shermanii | Sodium Lactate | ND |

| Saccharomyces boulardi | Acidified Potato Dextrose Agar | 20 x 107 |

EXPERIMENT-5:

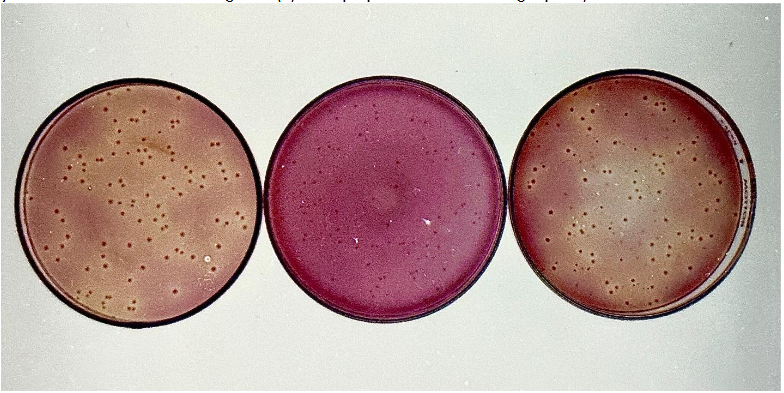

This experimental design is the same as Experiment 4, except in addition to the above specified probiotic organisms listed in Experiment-4, L. lactis var. lactis (SL-2), L. lactis var. cremoris (SC-2), L. lactis var. lactis ssp. diacetylactis (SD-2), Streptococcus thermophilus (ST-A), and Lactobacillus bulgaricus (LB-A), to study the compatibility upon growth as a mixed probiotic culture, to successfully formulate the multiple-mixed strain probiotic culture along with their immunomodulins, which can have superior therapeutic effects on preventing or treating dysbiosis in the GI tract. In addition, to the selective agars, we have used to enumerate the members of the genus Enterococcus, Propionibacterium, and Saccharomyces, we have also used Lee’s differential agar, and the Lactose+ve and Lactose-ve differential agar, to determine the survival of acid producers in the blend when all of them were grown together. Since it is not possible to differentiate the Lactococcus strains, Reddy’s double and triple differential agars were not used. The Lee’s agar fortified with 0.1% urea was specifically used to check for the sucrose positive S. thermophilus strains. Whereas Lac+ve and Lac-ve differential agar was used to enumerate the lactic acid producers in the blend. The lactose positive acid producers appeared as larger yellow colonies, whereas lactose negative mutant strains appeared small and pink. This is present in Figure-6. The results of the experiment with bacterial counts are presented in table-5. The results proved that most of the probiotic strains included in the probiotic mixed culture did not exhibit any strain dominance, since we have screened and eliminated earlier the probiotics with dominant behavior to suppress other probiotics in the blend.

| Genera and Species | Selective differential media used | Bacterial Counts at Different Lengths of Incubation (in HRS) |

|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecium | KF Streptococcus Agar | 55 x 107 |

| Propionibacterium shermanii | Sodium Lactate | ND |

| Saccharomyces boulardi | Acidified Potato Dextrose Agar | 10 x 107 |

| Streptococcus thermophilus | Lee’s Differential Agar fortified with Urea | 20 x 107 |

| Lactose positive and negative acid producers | Lactose Positive and Lactose Negative Differential Agar | 50 x 107 |

Discussion:

The results of the investigation proved that some of the probiotic cultures do exhibit undue strain domination when grown together with other probiotic strains. The techniques and methodologies of studying strain dominance among probiotic strains, using Reddy’s double and triple differential agars and broths to differentiate the probiotic species belonging to genus Lactococcus is of immense importance to arrive at the compatible strains to be used in the therapeutic probiotic formulations by the pharmaceutical companies. The Lee’s differential agar was an excellent tool to study the strain dominance between the probiotic strains belonging to genus Streptococcus and Lactobacillus, since these beneficial bacteria are extensively used in commerce to formulate probiotic blends. This investigation has also proven that strain dominance is more observed among Lactococcus species, perhaps due to their acid production and proteolysis is linked to the extrachromosomal genes (plasmids) rather than the chromosomal genes. Whereas such strain dominance was not significant when S. thermophilus was grown in combination with the Lactobacillus bulgaricus. Perhaps this is once again linked to the lack of lactose and casein plasmids in S. thermophilus strains. Although some of the lactobacillus species such as L. lactis have plasmids coding for beta galactosidase enzyme and caseolytic enzymes, yet they did not exhibit dominance over the probiotic strains of S.thermophilus tested. Yet, the pairing of the probiotic strains is essentially important even with S. thermophilus and strains of Lactobacillus to eliminate domination. In addition, Lactose positive (Lac +ve) and Lactose negative (Lac -ve) differential agar (whose composition is outlined under the Materials and Methods section of the experiment 5), can be used to determine the lactic acid producers in the multiple mixed-strain probiotics vs. nonacid producing mutants, since acid producers are essential to control pH in the GI tract.

The main theme of this research project was to develop multiple mixed-strain therapeutic pharmaceutical blends, which when repeatedly administered should be able to prevent or treat Dysbiosis, which is an improper or pathologically disproportionate balance among members of the multiple genus and species constituting the GI tract Microbiota. Until now, the probiotic cultures were blended without thoroughly determining such comparability among components in the mixed culture which can grow harmoniously without dominating each other. Specifically, when someone is trying to blend probiotics belonging to different genera. For that matter, even blending species belonging to the same genus. In order to conduct these studies, proper methodologies and procedures have to be developed. The main purpose of making a mixed probiotic culture is to take advantage of the therapeutic benefits offered by each individual probiotic strain in the blend. In this study we have not only outlined how to blend the compatible probiotics, but also their sustenance as they go through the GI tract. In this connection it is worthwhile to mention that some probiotic strains of Lactococcus lactis var. lactis produce the antibiotic Nisin, which will inhibit some Lactococcus lactis var. cremoris. Conversely, some strains (but not all) of Lactococcus lactis var. cremoris produce an antibiotic called Diplococcin to inhibit the growth of its closely related probiotic culture Lactococcus lactis var. lactis. The probiotic culture Lactobacillus acidophilus (only some strain) produce a bacteriocin called Acidophilin, whereas Streptococcus thermophilus produce a bacteriocin called Thermophilin, and Propionibacterium produce Propionicin, etc. etc. These antibiotics and bacteriocins are produced and directed not only against members of their own species (belonging to the same genus), but also against a variety of microorganisms including both beneficial and pathogenic bacteria. In one aspect it is good some of these probiotic bacteria have either chromosomal or extrachromosomal plasmid genes to code for these inhibitors in order to protect themselves from suppression by other bacteria. In other aspects, we do not want them inhibiting good probiotic cultures either. As microbiologists, it is our duty to check and make sure that the probiotics blended in the multiple mixed-strains do not dominate each other by elaborating these specific antibiotics and/or bacteriocins and/or therapeutic peptides. This is the reason why we have to undertake thorough studies to understand and observe the compatibility among these probiotic cultures.

In Experiment 1, we have seen that the probiotic combination of Lactococcus lactis var. lactis (SL-2) and Lactococcus lactis var. cremoris (SC-2) was highly incompatible exhibited by the domination of probiotic L. cremoris over L. lactis. This domination can be due to the production of inhibitory bacteriocins and/or differential growth rates and/or due to some unknown inhibitory factor. It appears that L. cremoris was sensing the specific molecular patterns on the cell wall of L. lactis more like “Pathogen Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs)” (although L. lactis is not a pathogen), by its “Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs),” thus triggering the intra and extracellular response to suppress its growth. In this instance, rather than calling them as PAMPs (as in the case of pathogens), we can name them as “Competition Associated Molecular Patterns (CAMPs). “ The other possible explanation is my recent finding, i.e. the production of microRNAs of one probiotic strain (although by nature they are produced primarily to stop their own excess growth or multiplication by preventing translation of mRNA coding for growth proteins during stationary phase), liberated or excreted outside the probiotic bacterial cell and gaining entrance into other member of the probiotic species to stop or slow its growth, thereby exhibiting domination. For the first time in bacteriology, I named the prokaryotic (probiotic) produced microRNAs as “mega-microRNAs (memiRNAs).” Earlier we have discovered that when two probiotic cultures are grown together, if one senses a threat from the other, it can produce and discharge memiRNAs to block or slow the growth of other bacteria. Of course in this case, the assumption is that domination is not due to production of antibiotics or bacteriocins, etc.. In Experiments 1 and 2, probiotic strains were not producers of antibiotics Nisin or Diplococcin. Both the probiotic organisms were equally competent in terms of nutrient utilization, rate of acid production, and rate of growth etc. when they were grown separately. Thus the only possible explanation for the observed strain dominance, when they were grown together, was either due to improper or misreading of the molecular patterns on the cell wall of L. lactis by L. cremoris as CAMPs, and thus releasing memiRNAs to block or slow down the growth of L. lactis. Apparently, it is a natural phenomenon and therefore it is the responsibility of the formulator to blend probiotic organisms which do not compete with each other when they are grown together. As an illustration, probiotic culture Combination-1, in Experiment 1 involving the probiotic strains L. lactis (SL-1) and L. cremoris (SC-1), showed that both probiotic strains were highly compatible and did not exhibit any strain dominance. A similar pattern was observed in Experiment 2, where in Combination-1 having three different species of probiotics were not compatible, whereas in Combination-2 no such strain dominance was observed. From the results of Experiment 3, it is surprising to note that the probiotics belonging to different genera and species, such as Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus when grown together did not exhibit any undue domination over other and they were highly compatible.

The results of Experiment 4 proved that domination of one probiotic culture over other among the probiotic cultures belong to genus Enterococcus, Propionibacterium and yeast Saccharomyces, when grown together was not evident, indicating they did not tend to dominate each other. In addition, when all the compatible probiotic cultures used in Experiments 1-4 were mixed and allowed to grow together, the component balance was maintained well without any of the undue strain domination observed in Experiment 5, proven by the number of colony-forming units representing each probiotic determined using differential and selective bacteriological media. Overall, the results of this investigation proved that although strain dominance among probiotic cultures is a natural phenomenon, we can still get around it by undertaking compatibility studies to make successful blends of multiple mixed strain probiotics, which can then be used to prevent or treat several diseases associated with Dysbiosis. Perhaps such domination among the undefined microbial strains present in the GI tract may be one of the causes for Dysbiosis, leading to disturbances in the immune system and leading to several viral (including COVID-19 and Long Covid) and bacterial infections (all pathogenic bacteria including Hospital Acquired Infections such as C.diff and MRSA,etc.) and other intestinal diseases including Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Colitis, chronic diarrhea and recurrent constipation, and certain cancers etc.. The maintenance of component balance among the micro-organisms of Microbiota is an essential requisite for optimum immunity and good health.

In this investigation we have proved that selective agars must be used to study the associative growth relationships among the probiotic bacterial strains belonging to genus Enterococcus, Propionibacterium, and the beneficial yeast probiotic culture Saccharomyces boulardii etc. By using the proven methodologies outlined in this publication, pharmaceutical and/ or nutraceutical and/ or culture companies involved in manufacture of the therapeutic probiotics, can formulate the best and superior functional Mixed Strain Probiotic blends by choice rather than chance. In addition, the methodologies outlined in this investigation can also be used – and in fact have already been used – clinically to study the human Microbiota by plating fecal samples on both the selective and differential agars. The number of Enterococcus, Propionibacterium, yeasts, and lactic acid producing bacteria present in a fecal sample (of course in addition to others), will dictate the status of the GI tract Microbiota and the overall health of human being. Although we did not mention it in this article, fecal coliforms have been enumerated in feces using selective Bacteriological agar: Violet Red Bile Agar. Whereas the members of the genus Lactobacillus has been selectively isolated or enumerated using MRS agar. As a hypothetical example, if the fecal sample came out negative or significantly low in numbers of Propionibacterium species, it is an indication that there is an imbalance in the Microbiota. Thus, a physician can recommend a particular probiotic blend with a high number of Propionibacterium strains. On the contrary, if the number of acid-producing bacteria are low in feces, the gut needs more acid producers to keep the pH slightly towards acidic side to reduce the pathogenic bacterial invasion. This can be corrected by developing and administering Multiple mixed-strain probiotics with significantly a greater number of their components represented by the acid-producing probiotic bacteria. If there is a preponderance of species of Enterococcus and Coliforms observed in fecal samples, perhaps the therapeutic probiotic blend should be made of significantly higher number of compatible strains of Streptococcus thermophilus and strains belonging to the genus Lactobacillus.

To date, no such advanced pharmaceutical grade therapeutic probiotic blends designed to treat or prevent a particular ailment with accuracy are available, despite the fact that there are a lot of discussions to replace antibiotic therapy with probiotic therapy. Thus, the treatment modality in clinical medicine is turning out like a hit-or-miss proposition. These techniques outlined in this research article are aptly applicable not only to develop highly successful and functional probiotics for human application, but also can be used successfully to develop customized products for improving the health of Poultry, Ruminants, as well as mono gastric pet animals, dogs and cats etc. Considering the recent increase in zoonotic diseases including the latest Bird Flu virus (H5N1) infecting poultry, cows and humans, it is a must that not only animals involved in food chains but also pets must be protected from the transmissible viral and bacterial diseases, to further protect pet owners and humanity at large. The techniques and procedures outlined in this investigation can be further modified by the competent microbiologists to adapt to various other applications, especially in the arena of treating Hospital acquired infections (Nosocomial Infections) and certain cancers etc., which are killing millions of innocent people each year. In my humble opinion, Multiple Mixed Strain Probiotic Therapy, developed with the use of compatible probiotic strains, is the only alternative to Antibiotic Therapy, to reduce or eliminate the antibiotic resistant Superbugs, which are projected to kill over 50 million people annually by the year 2050.

Conclusion:

Since the existence of strain dominance among probiotic bacteria has been established beyond doubt in this study, multiple mixed strain probiotics must be formulated by only including compatible probiotic strains. In addition, proprietary probiotic blends can be formulated by the manufacturers to prevent or treat a particular deficiency or disease by developing functional probiotic blends by following the methodologies outlined in this investigation. Using the procedures outlined in this research article, it has been determined that the multiple mixed strain probiotics, along with their immunomodulins used in formulating therapeutic formulations listed in the US Patent # 11,077,052 B1, were highly compatible and did not exhibit any strain domination. This could be the main reason why the novel patented therapeutic probiotic formulations were extremely effective in preventing and/ or treating SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus infection and the COVID-19 associated secondary pathogenic bacterial, yeast, and mold infections. Such patented formulas like the ones listed in US patent # 11,077,052 B1 can also be used (and have already been used) to successfully to prevent or treat all other RNA/DNA viruses, long COVID and nosocomial infections, etc. and as adjuvants to treat certain cancers.

By all means, the methodologies outlined in this investigation can be further modified by competent microbiologists, scientists, and medical professionals not only to develop superior blends of custom therapeutic probiotics, but also to use them as diagnostic tools to study the healthy or disease-affected individuals Microbiota, as an aid to prevent or treat the diseases by improving immunity through proper orchestration of immunomodulation.

Disclosure:

The author is a scientist with degrees in Veterinary Medicine, MS degree in Microbiology, and Ph.D. in Bacteriology, Virology, and Food Technology from Iowa State University, USA. He has been conducting research on probiotics for over 55 years and has published over 170 research articles and has over 150 national and international patents. He serves as a president of IMAC, Inc. in Denver, Colorado, USA. IMAC, Inc. is involved in the manufacture of food-grade beneficial bacterial cultures and other high-tech enzyme fortified functional products to go into manufacturing of various dairy products in United States, Canada, Europe, Asia, Korea, and South America.

Acknowledgements:

I am extremely thankful and grateful to Mr. Venkat (V.R.) Mantha, an eminent microbiologist who has over 40 years of experience in studying the bacterial interactions using several bacteriological differential media and starter media etc., for evaluating and critiquing the results of this research project. Mr. Mantha is the director of Quality Control, and Research and Development of International Media and Cultures (IMAC), a division of American Dairy and Food Consulting Laboratories, Inc., of Denver, Colorado, USA. He has critically evaluated the results of this project, specifically the validity of microbiological techniques developed and adapted to conduct the compatibility studies about therapeutic probiotic strains. In addition, he has coded, compiled the data, and helped me to prepare this highly technical journal publication. My sincere appreciation to Mr. Sridhar Reddy, a molecular biologist for editing and preparing the tables and presented in this publication. Also, my thanks are extended to Mr. Rasheed Hussain for rendering his professional help in photographing and preparing the photographs used in this manuscript. Sincere thanks are extended to all the individuals and fellow scientists, especially to Honorable Malireddy Jala Reddy, Dr. Ebenezer R. Vedamuthu, Dr. George W. Reinbold and Dr. Paul A. Hartman for encouraging me to undertake this long-lasting project, which of immense importance to improve the health and welfare of humanity at large.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References:

- Reddy MS. Mechanism of Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: How Can Probiotics Combat It? JAAPI. 2021; 1 (3): 27-35.

- Reddy MS, Reddy DRK. Therapeutic probiotics for cancer reduction. AAPI journal/ May/ June. 2015: 55-56.

- Reddy MS, Reddy DRK. Probiotics, biotechnology, and Ayurvedic herbs – complementary and alternative medicine. AAPI Journal / May/ June. 2004: 32-33.

- Shreiner AB, Kao JY, Young VB. The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015;31(1):69. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000139.

- FAO/WHO. Report on joint FAO/WHO. Expert consultation on evaluation of health and nutritional properties of probiotics in food including powdered milk with live lactic acid bacteria. 2001. http://www.fao.org/3/a0512e/a0512e.pdf

- Code of Federal Regulations of Food and Drug. Published by office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, U.S. Government printing office, Washington, D.C., USA. 2001. http://bookstore.gpo.gov

- Joint FAO/WHO Working group report on drafting guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food. Ontario: 2002. https://www.who.int/foodsafety/fs_management/en/probiotic_guidelines.pdf

- Anukam KC, Reid G. Probiotics: 100 Years (1907-2007) after Elie Metchnikoff’s Observation. Communicating Current Research and Educational Topics. Trends in Applied Microbiology 1907; 466-474.

- Reddy MS. Probiotics: Genesis, current definition, and proven therapeutic properties. JAAPI. 2021; 1 (2): 18 – 26.

- Metchnikoff E. The prolongation of life. Optimistic studies. London: Butterworth-Heinemann. 1907. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/51521

- Reddy MS, Reddy DRK.Development of multiple mixed strain probiotics for “Probiotic therapy “ under clinical conditions, to prevent or cure the deadly hospital acquired infections due to Clostridium difficile (C. diff) and Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Int J Pharma Sci Nanotech. 2016; 9 (3): 3256- 3281.

- Reddy MS. Immunomodulatory effect of “ Dr. M.S. Reddy’s Multiple Mixed Strain Probiotic Therapy “ to cure or prevent hospital acquired (Nosocomial) infections due to Clostridium difficile (C. diff), other pathogenic bacteria and autoimmune diseases. Int J Pharma Sci Nanotech. 2018; 11(1): 3937- 3949.

- Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336(6086):1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490.

- Mallina R, Craik J, Briffa N, Ahluwalia V, Clarke J, Cobb A. Probiotic containing Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and Streptococcus thermophiles (ACTIMEL) for the prevention of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhoea in the elderly with proximal femur fractures. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11(1):85–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.04.001.

- Allen SJ, Jordan S, Storey M, Thornton CA, Gravenor MB, Garaiova I et al. Probiotics in the prevention of eczema: a randomised controlled trial. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2014;archdischild-2013-305799.

- Anderson JW, Gilliland SE. Effect of fermented milk (yogurt) containing Lactobacillus acidophilus L1 on serum cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic humans. J Am Coll Nutrition 1999; 18:43-50.

- Reddy MS, Reddy DRK. An insight into the 2016 Best Medical Award-Winning Breakthrough Microbial and Nanotechnology based discovery of Dr. M.S. Reddy’s Multiple Mixed Strain Probiotic Therapy, to successfully treat the Nosocomial infections. Nano Technol Nano Sci.2017;1(1): 2-5.

- Reddy MS. Immunomodulatory effect of “Dr. M.S. Reddy’s Multiple Mixed Strain Probiotic Therapy” to cure or prevent hospital acquired nosocomial infections due to Clostridium difficile (C. diff), other pathogenic bacteria, and autoimmune diseases. Int J Pharma Sci Nano Tech. 2018;11:3937-3949.

- SoSS, Wan ML, El-Nezami H. Probiotics-mediated suppression of cancer. Curr Opi Oncol. 2017;29(1):62–72. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000342.

- Kich DM, Vincenzi A, Majolo F. Volken de Souza CF, Goettert MI: Probiotic: effectiveness nutrition in cancer treatment and prevention. Nutr Hosp. 2016;33(6):1430–1437.

- Hirayama K, Rafter J. The role of probiotic bacteria in cancer prevention. Microb Infect. 2000;2(6):681–686.

- Reddy, MS. Dr. M.S. Reddy’s Multiple Mixed Strain Probiotic Adjuvant Cancer Therapy, to complement immune check point therapy and other traditional cancer therapies, with least autoimmune side effects through eco- balance of human Microbiome. Int J Pharma Sci Nanotech. 2018; 11 (6): 4295- 4317.

- Nagata S, Chiba Y, Wang C, Yamashiro Y. The effects of the Lactobacillus casei strain on obesity in children: a pilot study. Beneficial Microb. 2017;8(4):535–543.

- Park M, Kwon B, Ku S, Ji G. The efficacy of bifidobacterium longum BORI and lactobacillus acidophilus AD031 probiotic treatment in infants with rotavirus infection. Nutrients. 2017;9(8):887.

- Acurcio L, Sandes S, Bastos R, Sant’Anna F, Pedroso S, Reis D, Nunes Á, Cassali G, Souza M, Nicoli J. Milk fermented by Lactobacillus species from Brazilian artisanal cheese protect germ-free-mice against Salmonella Typhimurium infection. Beneficial Microb. 2017;8(4):579–588.

- Reddy MS. Scientific and medical research on Dr. M.S. Reddy’s Multiple Mixed Strain Probiotic Therapy and its influence on assisting to cure or prevent the nosocomial infections, synergistically enhancing the conventional cancer therapies, as an adjuvant, and its possible potential to prevent or cure COVID -19 novel Coronavirus infection by balancing the intestinal Microbiota and Microbiome through modulation of the human immune system. Int J Pharma Sci Nanotech. 2020; 13(3): 4876- 4906.

- Reddy MS, Reddy DRK. Isolation and the determination of the major principle or causative agent behind the 2016 published breakthrough discovery of Dr. M. S. Reddy’s “ Multiple Mixed Strain Probiotic Therapy “, in successfully treating the lethal hospital acquired infections due to Clostridium difficile (C. diff) and Methicillin