Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery: Techniques & Insights

Angle-based Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery-procedures in glaucoma treatment

Karsten Klabe1 and Andreas Fricke2

- Internationale InnovativeOphthalmologie GbR; Martin-Luther-Platz 22/26; 40212 Düsseldorf, Germany

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 July 2025

CITATION: Klabe, K. and Fricke, A., 2025. Angle-based Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery-procedures in glaucoma treatment. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(7). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6761

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6761

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Surgical procedures for glaucoma are an increasingly important role in the treatment of glaucoma. The treatment is often necessitated due to structural alterations of the drainage mechanism, in the chamber angle, Schlemm canal and the distal collector channels. Surgical procedures are designed to lower intraocular pressure (IOP), thereby reducing the risk of visual impairment. Approximately 50-70% of the surgical procedures are minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS), which generally achieves a slightly lower IOP reduction than conventional filtering surgery, but with fewer complications. The selection of the MIGS procedure should be based on the severity of the glaucoma, the surgical skills of the surgeon, the desired target pressure and the patient’s individual needs.

Keywords

glaucoma, minimally invasive surgery, intraocular pressure, MIGS, surgical procedures

Introduction

Glaucoma is still the second leading cause of blindness. The most important risk factors for glaucoma-related blindness are the severity of the disease at diagnosis, bilateral disease, and age. Currently, the only effective approach to preserving visual function in glaucoma is the reduction of the intraocular pressure (IOP).¹ The first-line therapy for lowering intraocular pressure is usually the administration of medication in the form of eye drops. Poor compliance and tolerability can sometimes lead to treatment failure. The glaucoma treatment paradigm is evolving from a topical medications-first approach to a more proactive procedural approach, a shift that has been termed “interventional glaucoma”, for instance Selektive-Laser-Trabekuloplasty as first line treatment.² For progressive glaucoma with surgical intervention, ab externo filtration surgery is still considered the gold standard, but the procedure can lead to significant complications.³

In the last ten years, newer surgical procedures have become established, which are summarized under the term minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS). MIGS were developed as safer and less traumatic surgical procedures for patients with mild to moderate glaucoma or intolerance to standard medical therapy. They are characterized by an ab interno approach that causes minimal trauma and impact to the ocular anatomy, sparing the conjunctiva and allowing for rapid recovery.⁴ This does not apply for filtering surgical methods, which is why MIGS procedures are playing an increasing role in the treatment of patients with mild to moderate glaucoma. In addition, MIGS procedures can be combined very well with cataract surgery. Only ab interno procedures without a drainage cushion (isolated chamber angle interventions) can be described as MIGS. MIGS procedures tend to have a moderate IOP-lowering effect, but can reduce the medical burden.¹

The implementation of the therapeutic target IOP for glaucoma varies from patient to patient and requires individual procedures in order to achieve a maximum reduction in intraocular pressure (IOP). Compared to trabeculectomy with the use of cytostatics, MIGS generally achieves a slightly lower reduction in IOP. However, the major advantage of MIGS is the significantly improved intra- and postoperative complication rate. In addition, the broad spectrum of MIGS procedures available today enables more individualized glaucoma therapy.

This article focuses on the increasingly important role of MIGS, which offers a variety of surgical treatment options for glaucoma and enables early treatment of glaucoma. An up-to-date overview of the individual MIGS procedures is given here. Minimally invasive procedures with implantation of trabecular stent or suprachoroidal drainage implants and implant-free procedures such as ab interno variants of canaloplasty, trabeculotomy or trabeculectomy as well as “high-frequency deep sclerotomy” or excimer laser trabeculostomy are described.

Indications for Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgeries

Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery-procedures are considered for patients with mild to moderate visual field defects when drug therapy does not result in sufficient IOP reduction or IOP is above target pressure, patients are not adherent to treatment or it is suspected that patients are not adherent to treatment. In particular, by reducing the number of different topical medications, MIGS are a useful tool to improve patient adherence and therefore treatment outcomes. In addition, earlier intervention can help delay or avoid the need for more invasive surgery.

Approaches for Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgeries

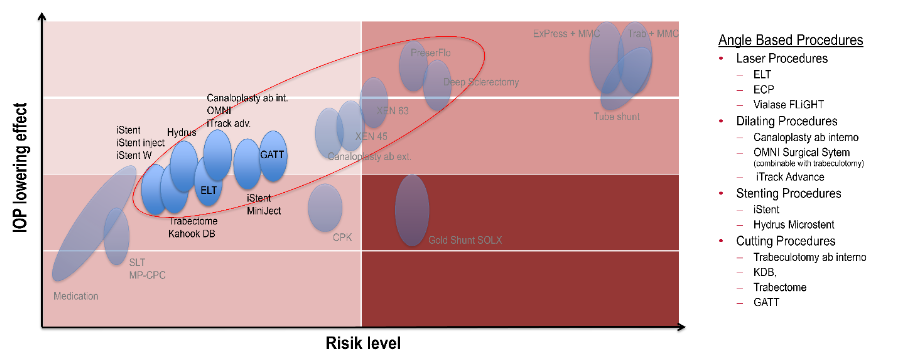

There is a wide variety of different surgical procedures, the majority of which address the structures of physiological ventricular outflow (trabecular meshwork, Schlemm’s canal, collector channels) to lower IOP.⁵ The different procedures can be divided into 4 groups:

-

procedures that reduce the outflow resistance with the aid of stents.

-

procedures that induce viscodilation of Schlemm’s canal and stretching of the trabecular meshwork.

-

procedures that completely or partially open or resect the trabecular meshwork.

-

procedures that promote uveoscleral outflow as an alternative drainage pathway via an ab- interno implant.

All minimally invasive glaucoma surgery-proceduresare glaucoma surgical procedures with the following characteristics:

-

ab interno access

-

efficient IOP-lowering

-

high safety profile

-

fast healing

-

minimal surgical trauma

The selection of the MIGS procedure should be based on the severity of the glaucoma, the surgical skills of the surgeon, the desired target pressure and the potential risks involved.

Cataract surgery and Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgeries

The proportion of cataract patients with simultaneously diagnosed glaucoma is around 10%.⁷ For these patients, MIGS opens up the possibility of treating both diseases in one procedure. MIGS procedures can be combined very well with cataract surgery, which is not the case in this extent with MIBS.

Almost all combined MIGS procedures are not inferior to simple phacoemulsification. Therefore, every ophthalmologist should consider simultaneous target pressure-oriented glaucoma surgery when performing cataract surgery on a glaucoma patient with clinically relevant glaucoma, as the advantages generally outweigh the disadvantages.

Contra-Indications for Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgeries

However, not all glaucoma patients can be treated effectively with MIGS. The most important exclusion criteria are as follows:

-

altered chamber angle anatomy (e.g. peripheral anterior synechiae)

-

poor chamber angle assessability (e.g. corneal scars)

-

low target pressure

-

advanced glaucoma with progression

-

high episcleral venous pressure (excl. suprachoroidal outflow)

-

massive bleeding tendency

-

several secondary glaucoma (e.g. neovascularization glaucoma)

Angle based Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery-procedures

TRABECULAR STENTS

iStents

The first generation of iStents® (Glaukos Corp., Aliso Viejo, CA, USA; 2004) consisted of an angled, half-open titanium tube that was implanted into Schlemm’s canal after perforation of the trabecular meshwork. The part located in Schlemm’s canal had denticle-like divisions that prevented dislocation. Ziaei et al.⁸ found a reduction in IOP from a preoperative mean of 21.3 to 16.4 mmHg 7 years after combined cataract surgery with implantation of a first-generation iStent. Preoperatively, a mean of 2.17 antiglaucoma drops were administered. After 7 years, after a gradual increase, it was 1.58 medications. Even without combined cataract surgery, it was shown in phakic and pseudophakic eyes that there is also a significant reduction in IOP and the amount of antiglaucoma medication required over the long term.⁹

With the second generation (iStent inject®, 2012), the implantation process was significantly simplified. With the help of a spring mechanism, a standardized application of 2 preloaded stents radially in the direction of the applicator’s guide needle was made possible at the push of a button. In addition, the design was changed to a short, heparin-coated titanium tube with an arrowhead-like head with barbed function. In a case series using anterior segment OCT (AS-OCT), Gillmann et al.¹⁰ showed that 72% of implanted iStent inject stents were not optimally positioned with the distal end of the stent in Schlemm’s canal and that a stent slightly raised above the level of the trabecular meshwork was associated with a better IOP-lowering function compared to a stent implanted too deep. However, if the iStent is placed correctly, a long-lasting effect of up to 7 years can be achieved.¹¹

Nevertheless, retrospective comparative studies have shown that the iStent inject achieves a higher IOP reduction after 6 and 12 months compared to implantation of the first-generation iStent.¹²,¹³ Further studies were unable to determine this significant difference in IOP reduction after 12 months. However, they were able to show that the topical antiglaucoma medication required is reduced more after iStent inject implantation.¹⁴

In the 3rd generation (iStent inject® W; 2018), the base plate of the stents has been enlarged compared to the 2nd generation with the same design in order to prevent implantation too deep into the trabecular meshwork. This enables more precise placement of the iStents, which are crucial for trabecular outflow improvement and thus for the achievable IOP reduction. With the iStent infinite®, 3 third-generation stents are currently implanted instead of the previous 2 stents. Sarkisian et al.¹⁵ have published the initial results of a multicenter study. In 72 eyes with a mean baseline IOP of 23.4 mmHg with an average of 3.1 topical antiglaucomatous medications, there was a reduction to an average of 17.5 mmHg and 2.7. Due to the high number of previous glaucoma operations (61 of 72 eyes), these results are only comparable to previous publications of the iStent generations to a limited extent.

Recent publications show that the use of the iStent infinite® achieves a small but clinically relevant and statistically significantly better reduction in non-medicated mean diurnal IOP with less surgical complications compared to Hydrus.¹⁶ And even in combined procedures with cataract surgery, it has been shown that there is a clinically and statistically significant reduction in intraocular pressure and medication intake up to 12 months after surgery with a low rate of side effects.¹⁷

The success of the implantation depends above all on optimal placement in the ciliary body band with a well-dosed contact pressure to prevent implantation too deep into the tissue. Immediately after optimal implantation, there is often minor reflux bleeding from the collector tubules in the ostia of the stents, which is usually self-limiting within a few days. Less frequently, recurrent anterior chamber hemorrhages occur weeks to months after stent implantation, which can be caused by uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome.¹⁸ Presumably triggered by mechanical

irritation, irritation occurs which can be calmed by removing the stents. In addition, stent occlusion and IOP spikes have been described as postoperative complications.¹⁹

Hydrus® Microstent

The Hydrus® Microstent (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) was also developed for trabecular implantation. At 8 mm in length, it is significantly larger than the iStents. Like the first generation iStent, the Hydrus is implanted laterally into Schlemm’s canal using the applicator after incision of the trabecular meshwork. Compared to the iStent, only the ostium, which is located at the transition from the anterior chamber to Schlemm’s canal, is tubular. The parts located further into Schlemm’s canal correspond to a semi-open scaffold with large fenestrations, which has a mechanically dilating effect on Schlemm’s canal and avoids the entrances to the collector tubules. Only one stent is implanted as standard. The HORIZON study showed that cataract surgery in combination with Hydrus implantation is superior to cataract surgery alone in terms of IOP reduction and drug reduction. This difference is still statistically significant 5 years after surgery,²⁰ as is the significant slowing of glaucoma progression based on visual field compared to cataract surgery alone.²¹ During the 5-year follow-up, the study also showed that the additional implantation of the microstent with cataract surgery did not lead to a higher endothelial cell loss.

In a non-randomized retrospective study, no statistically significant differences were found between Hydrus® and iStent inject® (2nd generation) in terms of IOP reduction and number of glaucomatous medications.²² A comparison of the two devices in combination with cataract surgery also revealed no significant differences.²³ However, other publications showed a superior IOP reduction and a more significant reduction in the need for antiglaucoma medication compared to the iStent inject® W.²⁴

The complications described to date are comparable to those of the iStent (IOP tips, hyphema, stent occlusion) and are serious in very few cases.¹⁹ Laroche et al.²⁵ showed in a small case series of 4 patients that postoperative malpositioning of the distal end of the stent in the anterior chamber can occur. As the Nitinol stents have the property of shape memory, this could lead to the stent bulging inwards and penetrating the trabecular meshwork with the ends in eyes with a larger diameter of the Schlemm’s canal than 12 mm.

CANALOPLASTY AB INTERNO

iTrack™ Advance, OMNI® Surgical System

Canaloplasty ab interno was developed as a modification of canaloplasty ab externo, in which Schlemm’s canal is partially opened and widened via an ab interno approach. Two systems are currently commercially available: the iTrack™ advanced microcatheter (Nova Eye Medical Limited, Kent Town, SA, Australia) and the OMNI® Surgical System (Sight Sciences Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA). Both systems are similar in application, but differ slightly in application details.

The OMNI Surgical System consists of a handle that ends in a curved hollow needle. The microcatheter is firmly integrated into the system, as is a reservoir that holds the viscoelastic. The trabecular meshwork is first opened selectively with a hollow needle tip. The microcatheter is then advanced into Schlemm’s canal using the advancement wheel and the canal is mechanically dilated. In a first step, approx. 180° of the circumference of Schlemm’s canal is probed. When the catheter is withdrawn – also via the advancement wheel – the viscoelastic is continuously released. The amount is approx. 11 µl. After rotating the instrument, the remaining 180° are treated according to the same principle.

With the iTrack™ Advance, the familiar iTrack microcatheter is integrated into a special handpiece that contains a mechanism that advances the catheter by means of a slider to such an extent that the entire 360° of Schlemm’s canal can be probed in a single surgery. When using the iTrack™ Advance, the preparation effort is slightly higher compared to the OMNI® system, but offers the advantage that the

canal can be probed under visualization (light guide up to the catheter tip) and the amount of viscoelastic to be applied can be varied as required.

Up-to-date publications show a significant and sustained reduction in pressure and medication when using the iTrack system and the OMNI system. In a first retrospective study, Gallardo et al.²⁶ compared canaloplasty ab interno as a stand-alone procedure (n = 41) with the combination with cataract surgery (n = 34). The pressure-lowering effect of 32.8% was slightly higher with the stand-alone procedure than with the combined procedure (31.7%). In the reduction of pressure-lowering medication, 36% of the canaloplasty eyes were medication-free, compared with 40% in the combined procedure. Both differences were not statistically significant. Comparable results are also reported by other authors.²⁷,²⁸ Compared to the ab externo variant, the pressure-lowering effect and the reduction in the amount of medication required are comparable to the classic ab externo canaloplasty without modification.²⁶

The ab interno variant is not only less invasive and conjunctiva-sparing, but is also characterized by a good safety profile. Due to physiological blood regurgitation from Schlemm’s canal, microhyphema was frequently observed as a sign of reflux bleeding. These usually do not need to be treated with further surgery.²⁸–³⁰

The advantages of canaloplasty ab interno therefore lie primarily in the shorter operating time and less invasiveness compared to the procedure ab externo. A combination with cataract surgery is also very well possible and can be introduced into the surgical routine without great effort.

TRABECULOTOMY AB INTERNO:

OMNI® Surgical System, iTrack™ Advance

With both the iTrack™ Advance and the OMNI® Surgical System can be used to perform a trabeculotomy after probing Schlemm’s canal. With iTrack™ Advance, this is performed by capturing the catheter tip with a second instrument (e.g. retinal forceps) and pulling out the catheter. This procedure is also known as gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy (GATT). With the OMNI system, the trabeculotomy is performed in three 180° steps, in which the catheter is not retracted but the tip of the cannula follows the course of Schlemm’s canal and thus opens the trabecular meshwork.

A retrospective observation with a 12-month outcome was the ROMEO study.³¹ This was a multicenter, retrospective, observational, single-arm study to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of canaloplasty and trabeculotomy with the OMNI® Surgical System in pseudophakic eyes with OAG. Eyes were stratified by baseline IOP, with group 1 >18 mmHg and group 2 ≤18 mmHg. Each group included 24 eyes of 24 patients. Primary success was defined as the proportion of patients with at least 20% reduction in IOP from baseline or an IOP between 6 and 18 mmHg and on the same or fewer medications without secondary surgical intervention up to 12 months after MIGS. Mean IOP was reduced in group 1 from 21.8±3.3 mmHg to 15.6±2.4 mmHg (28%) and in group 2 from 15.4±2.0 mmHg to 13.9±3.5 mmHg (10%). Medications went from 1.7±1.3 to 1.2±1.3 and from 2.0±1.3 to 1.3±1.3, respectively. 91% and 90% of eyes, respectively, required less medication than before MIGS treatment. Further results of retrospective observations after trabeculotomy/viscodilation are comparable and in the same range as results reported here.³²–³⁴

However, long-term data is key to the decision making in the selection of a surgical treatment. In the GEMINI extension study³⁵ and in the IRIS® registry study³⁶ showed that the effect of lowering IOP and reducing the need of glaucoma medications lasts up to 36 months. This applies to the combined operation of trabeculotomy/viscodilation with cataract surgery (GEMINI) or as a stand-alone procedure (IRIS).

Compared to pure canaloplasty ab interno, trabeculotomy/viscodilation approximately doubled the frequency of hemorrhages into the anterior chamber (0.97–50.6% of cases). There were also pressure peaks (0–22.2%) and corneal edema (0–

6.2%). Very rare complications were fibrinous uveitis, iridodialysis or iris trauma, hypotony, descemetolysis, cystoid macular edema, visual deterioration and choroidal detachment.¹⁹

TRABECULECTOMY AB INTERNO

Trabectome®

Compared to a classic goniotomy, the Trabectome® (Neomedix, Tustin, USA) not only incises the trabecular meshwork, but were removed over the and inner wall of the SC a 90°–120° range. At the same time as the ablation of the tissue, irrigation is carried out via an infusion to cool and suction of the ablated tissue. In addition to anti-inflammatory substances, pilocarpine should be administered for several weeks after the trabecular application to prevent the wound gap from sticking together and the collector channels from being tamponaded by iris tissue.

In a retrospective, non-randomized, matched comparison study with 39 eyes with open-angle glaucoma in each group, a slightly lower IOP reduction and a greater reduction in medication was found within the first 2 years with Trabectome® than with iStent inject® implantation. All operations were combined with cataract surgery.³⁷ In another retrospective comparative study by Kurji et al.³⁸ with 70 eyes, there were no significant differences in IOP reduction 12 months after combined cataract surgery with Trabectome® or first-generation iStents. However, complications (anterior chamber hemorrhages, pressure peaks) occurred significantly more frequently in the Trabectome® group. Pahlitzsch et al.³⁹ were able to show that there were no significant differences in IOP reduction between the individual procedures 3 years after Trabectome®, iStent inject® or SLT. Kono et al.⁴⁰ found an average IOP reduction of 20% in 305 eyes in a retrospective study 6 years after trabectome surgery.

In eyes with pseudoexfoliation glaucoma, 12 months and 36 months as well as in angle closure glaucoma with combined cataract surgery, goniosynechialysis and trabeculectomy ab-interno up to 36 months after surgery, good success rates in lowering IOP and reducing antiglaucomatous mucosa can be observed.⁴¹–⁴³

Early IOP decompensation of trabeculectomy ab interno with the Trabectome® occurred in about 20% of eyes. Half of them showed a spontaneous regression, the other half were persistent. Previous SLT and a high preoperative IOP were identified as prognostically unfavorable initial situations.⁴⁰,⁴⁴ In addition to frequent initial reflux bleeding from the collector channels and transient pressure peaks, unintentional cyclodialysis can also occur in rare cases.⁴⁵

Kahook Dual Blade®

Similar to the trabectome, the Kahook Dual Blade® (KDB; New World Medical, Rancho Cucamonga, CA) is used to ablate the trabecular meshwork in order to reduce trabecular outflow resistance. In contrast to classic trabeculectomy, the trabecular meshwork is not simply incised, but the tissue is removed with two parallel blades after plow-like penetration into Schlemm’s canal. These are disposable instruments which, unlike the trabectome, do not require an additional irrigation system. A second generation, the KDB Glide, has rounded edges at the base, which are modeled more on the concave shape of the back wall of Schlemm’s canal in order to cause less damage to the collector canals.⁴⁶

In a retrospective study with combined cataract surgery and KDB trabeculectomy showed a reduction in mean baseline pressure from 20.4 mmHg to 13.9 mmHg over 24 months (n = 46) and to 13.9 mmHg after 36 months (n = 16). The average number of medications required decreased from 3.2 to 1.4 and 2.0 agents respectively over the same period.⁴⁷ Long-term observations showed an effective reduction in IOP of approx. 28.0% compared to the initial value after up to 6 years with a simultaneous reduction in the drug load by an average of 31% and an excellent safety profile, regardless of the phacoemulsification status.⁴⁸ Another retrospective, multicenter study compared cataract surgery either combined with KDB trabeculectomy or with iStent implantation (single

stent, 1st generation). Within the first 12 months, KDB showed a slightly lower IOP reduction and lower drop savings than iStent (first generation).⁴⁹ However, this cannot be directly compared with the implantation of several iStents of the newer generations. Pratte et al.⁵⁰ published that the extent of intraocular pressure reduction after trabeculectomy with KDB depends on the baseline pressure and the number of antiglaucomatous agents. The higher the baseline pressure and the more medical burden, the greater the effect of the KDB.

In addition to, KDB goniotomy as a combined procedure with cataract also appears to be a safe and effective reduction of IOP and medical burden. In 12 months after surgery, the success rate for pseudoexfoliation glaucoma in terms of IOP reduction appears to be slightly higher than for open-angle glaucoma.⁵¹

Compared to the Trabectome®, slightly poorer tracking accuracy has been described when cutting in the trabecular meshwork, which is associated with an increased risk of incorrect cuts.⁵² Therefore, in addition to the very frequently occurring unproblematic reflux hemorrhages from the collector canals, more serious hemorrhages from the base of the iris can also occur.

The procedure should not be combined with the implantation of toric IOLs, as significant changes in corneal astigmatism may occur,⁵³ and also not in combination with a deep sclerectomy, as it can lead to postoperative hypotension and massive anterior chamber bleeding.⁵⁴

High Frequency Deep Sclerotomy

High-frequency deep sclerotomy (HFDS) is a procedure for high-frequency ablation of the trabecular meshwork and the adjacent sclera. The HFDS is served via an operating platform from Oertli (abee® Glaucoma Tip, Oertli Instrumente AG, Berneck, Switzerland). The procedure is well described in Pajic et al.⁵⁵ Normally, the sclera is penetrated 4 to 8 times through the trabecular meshwork and successively through Schlemm’s canal. Each time a pocket about 0.3 mm high and 0.6 mm wide is created.

Compared to other MIGS techniques, HFDS generally showed a more significant initial reduction in IOP. Published clinical data show a IOP reduction of up to 30–40% after combined surgery of phacoemulsification with subsequent HFDS with a significant reduction in medication up to 48 months after surgery and a low complication rate. The most common complications were hyphema in up to 26% of cases and postoperative pressure peaks in 19% of cases. No serious side effects have been reported to date.⁵⁶–⁵⁹

Excimer Laser Trabeculostomy

Excimer laser trabeculostomy (ELT) (EliosVision, MLase AG, Germering, Germany) is an invasive laser procedure with the aim of punctual opening of the trabecular meshwork. The wavelength varies in comparison to the excimer laser in corneal treatment (ELT 308 nm vs. 193 nm). The laser energy can be guided directly to the target location via a fiber. Ten 210 µm microperforations are shot into the trabecular meshwork in short pulses according to the existing treatment protocol. The first paper on ELT was published in 1987.⁶⁰

Recent clinical results show significant reduction in IOP of between (15–40%) with significant reduction of IOP-lowering medication of at least 1 or medication free of 50 to 75% up to 12 months after phacoemulsification-ELT.⁶¹–⁶³ The IOP reduction for standalone as well as for combined surgery with phacoemulsification in patients with open-angle glaucoma was stable for up to 8 years.⁶⁴,⁶⁵

The complication rates were low in all publications. Pressure spikes in 10–15% and hyphema in less than 10% were the most common side effects. No serious complications were reported.

SUPRACHOROIDAL DRAINAGE

CyPass®, iStent supra®, MINIject®

In 1905, Heine recommended partial cyclodialysis as a promising intervention for significantly and permanently lowering intraocular pressure.⁶⁶ In the

following decades, there were numerous other ideas for using the suprachoroidal outflow tract to lower IOP.⁶⁷,⁶⁸ Around a century later, the technology experienced a renaissance as part of the newly emerging MIGS.

A first MIGS-device is the Cypass Microstents (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA). The suprachoroidal stent was approved in Europe in 2008 (CE certificate) and in the USA in 2016 (FDA approval 2016). Initial study results showed a promising pressure reduction of 20% to 30% with a simultaneous reduction in medication over 2–3 years.⁶⁹–⁷¹ However, the COMPASS XT follow-up study showed a significant loss of corneal endothelial cells after 5 years with anterior stent implantation.⁷² Some of ocular events were serious such as visual impairment and/or corneal decompensation. Shortening of the stents was therefore recommended. At the same time, the stent was voluntarily withdrawn from the market in 2018.

Another suprachoroidal stent, the iStent supra (Glaukos, San Clemente, California), also showed a pressure-lowering effect of around 30% with a significant reduction in medication in initial clinical studies, but has never been launched on the market despite CE approval since 2010.⁷³

In December 2021, another stent to improve uveoscleral outflow was launched on the market – the MINIject® (iStarMedical, Wavre, Belgium). The MINIject® is implanted into the suprachoroidal space via a special injection system after a small local cyclodialysis has been created. Only an approx. 0.5 mm long part protrudes into the anterior chamber to prevent damage to the endothelium. The results to date are predominantly from approval studies and show an average reduction in intraocular pressure of up to 39% over 2 years with a simultaneous reduction in medication from at least 1 medication after 24 months. The decrease of corneal endothelial cell count after two years is reported to be around 6%.⁷⁴–⁷⁶ There were no clinically significant differences in IOP reduction and glaucoma medication or glaucoma progression based on MD in the visual field when comparing MINIject® surgery standalone and combined MINIject® surgery with phacoemulsification in patients with open-angle glaucoma.⁷⁷ The overall complication rate was low and usually not severe. The most common complications in the STAR-I–II clinical studies were anterior chamber irritation with reduced visual acuity, mild visual field defects, IOP pressure peaks, lens opacities in phakic eyes and hyphema. It is becoming apparent that the pressure-lowering potential in the treatment of uveoscleral outflow is stronger than with trabecular stents.⁷⁶–⁷⁸

Conclusion

Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgeries were developed as safer and less traumatic surgical procedures for patients with mild to moderate glaucoma or intolerance to standard medical therapy. By definition, they are characterized by an ab interno approach that causes minimal surgical trauma and disruption to the ocular anatomy, sparing the conjunctiva and allowing for a quick recovery. The variety of different procedures with comparable pressure reduction and comparable risk profile makes the question “Which operation for which patient?” difficult in individual cases. The only consensus is that MIGS procedures are more suitable for mild to moderate glaucoma. Some important issues are still the subject of lively debate. It has not yet been fully clarified whether it is justified to perform the procedures predominantly in combination with cataract surgery or whether a standalone procedure is preferable. The question of whether the reduction of glaucoma medication alone is sufficient to indicate surgical intervention is also still being discussed.⁷⁹–⁸¹

The focus is often on details (implants vs. no implant, alternative vs. physiological drainage, excision of tissue vs. perforation only, limited vs. extensive treatment area) that pay less attention to the actual and recognized therapeutic goal – a significant reduction in intraocular pressure – and are rather an expression of a lack of clear differentiation. To simplify the decision-making process, we should consider the individual aspects of the various procedures and derive the individual therapy from this. The intraocular pressure to be achieved after the procedure (target

IOP concept) is and remains the most important decision criterion. Other aspects such as coexisting cataract, previous operations, condition of the conjunctiva, but also age, stage of glaucoma and rate of progression as well as other concomitant diseases and patient preferences should and must be taken into account in the indication process.¹

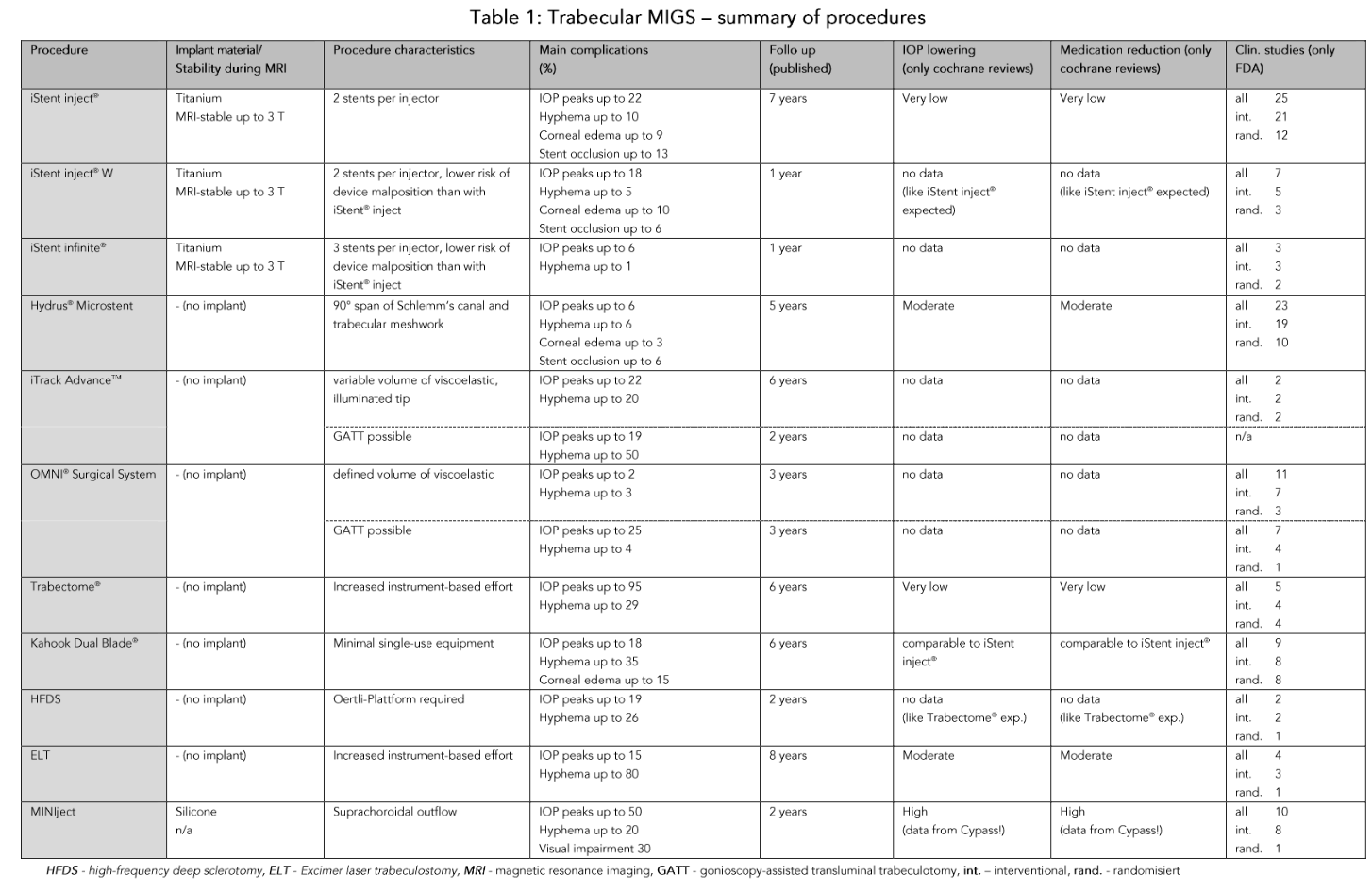

The average target IOP that can be achieved with MIGS is generally higher than with classic filtration surgery or subconjunctival stents. Postoperative IOP values of 14 mmHg and less without additional medication are rare. Table 1 compares various aspects of the procedures discussed here. In particular, the available Cochrane Reviews can be valuable aid in deciding whether and, if so, which MIGS procedure should be chosen. The IOP-lowering potential and the chance of freedom from glaucomatous medication appear to be higher for the suprachoroidal than for the trabecular outflow pathway. In the latter case, implants with a larger treatment area (Hydrus® Microstent) appear to be slightly more effective than a smaller treatment area (iStent). However, this effect can be partially offset by increasing the number of stents.¹⁶ In contrast, resection of the trabecular meshwork does not appear to have any advantages over a stent in terms of pressure reduction and freedom from medication.

In summary, it must be noted that even after more than a decade of MIGS, the evidence regarding the reduction of intraocular pressure and/or the reduction of patients’ medication burden is still low for many procedures and therefore further high-quality studies are needed to derive clear guidelines for the use of the individual procedures. It will also need to be clarified whether the use of antifibrotic agents in the trabecular meshwork or in the suprachoroidal space can improve the long-term outcome after various MIGS procedures.⁸²–⁸⁵ It has been shown that MIGS procedures can be combined with different mechanisms of action and have an additive effect.⁷³ This could lead to the development of new glaucoma therapies, also in combination with implantable drug-induced slow-release systems, which will be available in the near future and enable comparable IOP lowering to fistulating surgical procedures with significantly reduced surgical risk.

Conflict of interest statement:

Karsten Klabe is a consultant for AbbVie, Alcon, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Elios Vision, iStar Medical, Oertli and Vialase, has receiving speaking fees from AbbVie, Alcon, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Elios Vision, iStar Medical, Santen and Vialase, and receives research support from AbbVie, Alcon, Carl Zeiss Meditec, EyeD Pharma and iStar Medical.

None of the authors has any financial interest or any conflict of interest related to the subject matter.

Funding statement:

This article did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. European Glaucoma Society. Terminology and Guidelines for Glaucoma. 5th edition. Savona, Italy: PubliComm; 2021.

2. Funke CM, Ristvedt D, Yadgarov A, Michiletti JM. Interventional glaucoma consensus treatment protocol. Expert Review of Ophthalmology. 2025; 20(2):79-87

3. Lavia C, Dallorto L, Maule M, Ceccarelli M, Fea AM. Minimally-invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) for open angle glaucoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183142.

4. Brusini P, Filacorda S. Enhanced Glaucoma Staging System (GSS 2) for classifying functional damage in glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2006;15(1): 40–46

5. Klabe K, Rüfer F. [Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery-Comparison of angle based procedures]. Ophthalmologie. 2023;120(4):358-371.

6. Hoffmann EM, Hengerer F, Klabe K, et al. [Glaucoma surgery today]. Ophthalmologe. 2021 Mar;118(3):239-247.

7. Deutsche Ophthalmologische Gesellschaft. Weißbuch zur ophthalmologischen Versorgungssituation in Deutschland. Munich, Germany: DOG; 2023.

8. Ziaei H, Au L. Manchester iStent study: long-term 7-year outcomes. Eye. 2021;35(8):2277–2282.

9. Lavia C, Dallorto L, Maule M, Ceccarelli M, Fea AM (2017) Minimally-invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) for open angle glaucoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e183142.

10. Gillmann K, BravettiGE, Mermoud A, et al. A prospective analysis of iStent inject microstent positioning: Schlemmcanal dilatation and Intraocular pressure correlations. J Glaucoma. 2019;28(7):613–621.

11. Hengerer FH, Auffarth GU, Conrad-Hengerer I. 7-Year Efficacy and Safety of iStent inject Trabecular Micro-Bypass in Combined and Standalone Usage. Adv Ther. 2024;41(4):1481-1495.

12. Guedes RAP, Gravina DM, Lake JC, et al. Intermediate resultsof iStent or iStent inject implantation combined with cataract surgery in a real-world setting: a longitudinal retrospectivestudy. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8(1):87–100.

13. Manning D (2019) Real-world case series of iStent or iStent inject trabecular micro-bypass stents combined with cataract surgery. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8(4):549–561.

14. Shalaby WS,Lam SS, Arbabi A, et al. iStent versus iStent inject implantation combined with phacoemulsification in open angle glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(9):2488–2495.

15. Sarkisian SR Jr, Grover DS, Gallardo M, et el. Effectiveness and Safety of iStent Infinite Trabecular Micro-Bypass for Uncontrolled Glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2023;32(1):9–18.

16. Ahmed IIK, Berdahl JP, Yadgarov A. Six-Month Outcomes from a Prospective, Randomized Study of iStent infinite Versus Hydrus in Open-Angle Glaucoma: The INTEGRITY Study. Ophthalmol Ther. 2025;14 (5):1005-1024.

17. Vest Z, Alinaghizadeh N, Prendergast C. Third-Generation Trabecular Micro-Bypass Implantation with Phacoemulsification for Glaucoma. Ophthalmol Ther. 2025;14(3):529-539.

18. Siedlecki A, Kinariwala B, Sieminski S. Uveitis glaucoma-hyphema syndrome following iStent implantation. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2022;13(1):82–88.

19. Rowson AC, Hogarty DT, Maher D. et al. Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery: safety of individual devices. J Clin Med. 2022;11(22):6833.

20. Ahmed IIK, De Francesco T, Rhee D, et al. Long-term outcomes from the HORIZON randomized trial for a Schlemm’s canal microstent in combination cataract and glaucoma surgery. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(7):742–751.

21. Montesano G, Ometto G, Ahmed IIK, et al. Five-Year Visual Field Outcomes of the HORIZON Trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2023;251:143-155.

22. Holmes DP, Clement CI, Nguyen V, et al. Comparative study of 2-year outcomes for hydrus or iStent inject microinvasive glaucoma surgery implants with cataract surgery. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022;50(3):303–311.

23. Komzak K, Allen PL, Toh T. Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery: comparison of Hydrus microstent with iStent inject in primary open-angle glaucoma. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2025;10(1):e001946.

24. Weich C, Zimmermann JA, Storp JJ, et al. Comparison of the Intraocular Pressure-Lowering Effect of Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) iStent Inject W and Hydrus-The 12-Month Real-Life Data. Diagnostics (Basel). 2025;15(4):493.

25. Laroche D, Martin A, Brown A, et al. Mispositioned hydrus microstents: a case series imaged with NIDEK GS-1 gonioscope. J Ophthalmol. 2022; 2022:1605195.

26. Gallardo MJ, Supnet RA, Ahmed IIK. Circumferential viscodilation of Schlemm’s canal for open-angle glaucoma: ab-interno vs ab-externo canaloplasty with tensioning suture. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:2493–2498.

27. Koerber N, Ondrejka S. 6-Year Efficacy and Safety of iTrack Ab-Interno Canaloplasty as a Stand-Alone Procedure and Combined With Cataract Surgery in Primary Open Angle and Pseudoexfoliative Glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2024;33(3):176-182.

28. Hughes T, Traynor M. Clinical results of ab interno canaloplasty in patients with open angle glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:3641–3650.

29. Toneatto G, Zeppieri M, Papa V, et al. 360° Ab-Interno Schlemm’s Canal Viscodilation with OMNI Viscosurgical Systems for Open-Angle Glaucoma-Midterm Results. J Clin Med. 2022;11(1):259.

30. Gallardo MJ. 24-month efficacy of viscodilation of Schlemm’s canal and the distal outflow system with itrack ab-interno canaloplasty for the treatment of primary open-angle glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:1591–1599.

31. Vold SD, Williamson BK, Hirsch L, et al. Canaloplasty and Trabeculotomy with the OMNI System in Pseudophakic Patients with Open-Angle Glaucoma: The ROMEO Study. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2021;4(2):173–81.

32. Klabe K, Kaymak H. Standalone Trabeculotomy and Viscodilation of Schlemm’s Canal and Collector Channels in Open-Angle Glaucoma Using the OMNI Surgical System: 24-Month Outcomes. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:3121–9

33. Ondrejka S, Körber N, Dhamdhere K. Long-term effect of canaloplasty on intraocular pressure and use of intraocular pressure-lowering medications in patients with open-angle glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2022;48(12):1388–93.

34. Grabska-Liberek I, Duda P, Rogowska M, et al. 12-month interim results of a prospective study of patients with mild to moderate open-angle glaucoma undergoing combined viscodilation of Schlemm’s canal and collector channels and 360° trabeculotomy as a standalone procedure or combined with cataract surgery. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022;32(1):309–15.

35. Greenwood MD, Yadgarov A, Flowers BE, et al. 36-Month Outcomes from the Prospective GEMINI Study: Canaloplasty and Trabeculotomy Combined with Cataract Surgery for Patients with Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:3817-3824.

36. Radcliffe NM, Harris J, Garcia K, et al. Standalone Canaloplasty and Trabeculotomy Using the OMNI Surgical System in Eyes with Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: A 36-Month Analysis from the American Academy of Ophthalmology IRIS® Registry (Intelligent Research in Sight). Am J Ophthalmol. 2025;271:436-444.

37. Al Yousef Y, Strzalkowska A, Hillenkamp J, et al. Comparison of a second-generation trabecular bypass (iStent inject) to ab interno trabeculectomy (trabectome) by exact matching. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(12):2775–2780.

38. Kurji K, Rudnisky CJ, Rayat JS, et al. Phaco-trabectome versus phaco-iStent in patients with open angle glaucoma. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017;52 (1):99–106.

39. Pahlitzsch M, Davids AM, Winterhalter et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versusMIGS: forgotten art or firststep procedure in selected patients with openangle glaucoma. Ophthalmol Ther. 2021;10 (3):509–524.

40. Kono Y, Kasahara M, Hirasawa K, et al. Long-termclinical results of trabectome surgery in patients with open-angle glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(11):2467–2476.

41. Pahlitzsch M, Davids AM, Zorn M, et al. Three-year results of ab interno trabeculectomy (trabectome): Berlin study group. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256(3):611–619.

42. Okeke CO, Miller-Ellis E, Rojas M, Trabectome Study Group. Trabectome success factors. Medicine. 2017;96(24):e7061.

43. Yang F, Ma Y, Liang Z, et al. Combined Phacoemulsification, Goniosynechialysis and Ab Interno Trabeculectomy in Primary Angle-closure Glaucoma: Long-term Results. Int J Med Sci. 2025;22(2):451-459.

44. Campisi V, Santos M, Gutkind NE, et al. Safety and efficacy profile of irrigating trabeculectomy (Trabectome®) in a Latin American population with moderate and advanced glaucoma. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed). 2025;100(3):143-149.

45. Berk TA, An JA, Ahmed IIK. Inadvertent Cyclodialysis Cleft and Hypotony Following Ab-Interno Trabeculotomy Using the Trabectome Device Requiring Surgical Repair. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(8):742-746.

46. Dorairaj S, Radcliffe NM, Grover DS, et al. A review of excisional goniotomy performed with the Kahook dual blade for glaucoma management. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2022;16(1):59–64.

47. Albuainain A, Al Habash A. Three-yearclinical outcomes of phacoemulsification combined with excisional goniotomyusing the kahookdual blade for cataract and open-angle glaucoma in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2022;36(2):213–217.

48. Vasu P, Abubaker Y, Boopathiraj N, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Excisional Goniotomy with the Kahook Dual Blade: 6-Year Results. Ophthalmol Ther. 2024; 13(10):2731-2744.

49. El Mallah MK, Seibold LK, Kahook MY, et al. 12-month retrospective comparison of Kahook dual blade excisional goniotomy with Istent trabecular bypass device implantation in glaucomatous eyes at the time of cataract surgery. Adv Ther. 2019;36 (9):2515–2527.

50. Pratte EL, Cho J, Landreneau JR, Hirabayashi MT, et al. Predictive factors of outcomes in Kahook dual blade excisional goniotomy combined with phacoemulsification. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2022; 16(1):47–52.

51. Koylu MT, Yilmaz AC, Gurdal F, et al. Kahook dual blade goniotomy combined with phacoemulsification in eyes with primary open angle glaucoma and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma: comparative study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025;25(1):184.

52. van Oterendorp C, Bahlmann D. Kahook Dual Blade : Ein Instrument zur mikroinzisionalen Trabekelwerkschirurgie. Ophthalmologe. 2019;116 (6):580–584.

53. Hirabayashi MT, McDaniel LM, An JA. Reversal of toric intraocular lens-corrected corneal astigmatism after Kahook dual blade goniotomy. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2019;13(1):42–44.

54. Chihara E, Chihara T. Outcome of Combined Kahook Dual Blade Surgery and Deep Sclerectomy: Adverse Effects of Postsurgical Low Intraocular Pressure. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2024;18(4):174-177.

55. Pajic B, Cvejic Z, Mansouri K, et al. High-Frequency Deep Sclerotomy, A Minimal Invasive Ab Interno Glaucoma Procedure Combined with Cataract Surgery: Physical Properties and Clinical Outcome. Appl. Sci. 2020;10(1):218

56. Pajic B, Pajic-Eggspuehler B, Haefliger I. New minimally invasive, deep sclerotomy ab interno surgical procedure for glaucoma, six years of follow-up. J Glaucoma. 2011;20(2):109–114.

57. Abushanab MMI, El-Shiaty A, El-Beltagi T, et al. The efficacy and safety of high frequency deep sclerotomy in treatment of chronic open-angle glaucoma patients. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019: 1850141.

58. Kontic M, Todorovic D, Zecevic R, et al. High-Frequency Deep Sclerotomy as Adjunctive Therapy in Open-Angle Glaucoma Patients. Ophthalmic Res. 2023;66(1):339-344.

59. Wang WX, Ko ML. Taiwan’s first clinical reports on the surgical effect of high-frequency deep sclerotomy for treating primary open-angle glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025 Feb 20;25(1):84.

60. Berlin MS, Rajacich G, Duffy M, et al.Excimer laser photoablation in glaucoma filtering surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103(5):713–714.

61. Durr GM, Töteberg-Harms M, Lewis R, et al. Current review of excimer laser trabeculostomy. Eye Vis (Lond) 2020;7:24.

62. Moreno-Valladares A, Vinokurtseva A, González-Rodríguez JM, et al. 12-month Intraocular Pressure and Hypotensive Medications Outcomes after Phaco-ELIOS Procedure – A Real World Study. J Glaucoma. 2025;Online ahead of print.

63. Gniesmer S, Sonntag SR, Grisanti S. [Efficacy and safety of the new generation of excimer laser trabeculotomy in a heterogeneous patient population-1-year follow-up]. Ophthalmologie. 2025 Jan;122(1):46-51.

64. Berlin MS, Shakibkhou J, Tilakaratna N, et al. Eight-year follow-up of excimer laser trabeculostomy alone and combined with phacoemulsification in patients with open-angle glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2022;48(7):838–843.

65. Riesen M, Funk J, Töteberg-Harms M. Long-term treatment success and safety of combined phacoemulsification plus excimer laser trabeculostomy: an 8-year follow-up study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022;260(5):1611-1621.

66. Heine L. [Cyclodialysis, a new glaucoma operation]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1905;31(21): 824-826. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1188143.

67. Erb C. [Suprachoroidal minimally invasive glaucoma surgery : Procedures and clinical outcome]. Ophthalmologe. 2018;115(5):370–380.

68. Jordan JF, Engels BF, Dinslage S, et al. A novel approach to suprachoroidal drainage for the surgical treatment of intractable glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2006;15(3):200–205.

69. Vold SA II, Craven ER, Mattox C, et al. Two-year COMPASS trial results: supraciliary microstenting with phacoemulsification in patients with open-angle glaucoma and cataracts. Ophthalmology. 2016; 123(10):2103–2112.

70. Grisanti S, Grisanti S, Garcia-Feijoo J, et al. Supraciliary microstent implantation for openangle glaucoma: multicentre 3-year outcomes. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2018;3(1):e183

71. Sandhu A, Jayaram H, Hu K, et al. Ab interno supraciliary microstent surgery for open-angle glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5 (5):CD12802.

72. Reiss G, Clifford B, Vold S, et al. Safety and effectiveness of CyPass supraciliary micro-stent in primary open angle glaucoma: 5-year results from the COMPASS XT study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019; 208:219–225.

73. Myers JS, Masood I, Hornbeak DM, et al. Prospective evaluation of two iStent® trabecular stents, one iStent supra® suprachoroidal stent, and postoperative prostaglandin in refractory glaucoma: 4-year outcomes. Adv Ther. 2018;35(3):395–407.

74. Denis P, Hirneiß C, Durr GM, et al. Two-year outcomes of the MINIject drainage system for uncontrolled glaucoma from the STAR-I first-in human trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022;106(1):65–70.

75. García Feijoó J, Denis P, et al. A European study of the performance and safety of MINIject in patients with medically uncontrolled open-angle glaucoma (STAR-II). J Glaucoma. 2020;29(10):864–871.

76. Dick HB, Mackert MJ, Ahmed IIK, et al. Two-Year Performance and Safety Results of the MINIject Supraciliary Implant in Patients With Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Meta-Analysis of the STAR-I, II, III Trials. Am J Ophthalmol. 2024; 260:172-181.

77. Dervenis P, Dervenis N, Lascaratos G, et al. Two-Year Data on the Efficacy and Safety of the MINIject Supraciliary Implant in Patients with Medically Uncontrolled Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. J Clin Med. 2025;14(5):1639.

78. Tan JCK, Agar A, Rao HL, et al. Meta-Analysis of MINIject vs. Two iStents as Standalone Treatment for Glaucoma with 24 Months of Follow-Up. J Clin Med. 2024;13(24):7703.

79. Radcliffe N. The case for standalone microinvasive glaucoma surgery: rethinking the role of surgery in the glaucoma treatment paradigm. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2023;34(2):138-145.

80. Fellman RL, Mattox C, Singh K, et al. American glaucoma society position paper: microinvasive glaucoma surgery. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2020;3 (1):1–6.

81. Paik B, Chua CH, Yip LW, et al. Outcomes and Complications of Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgeries (MIGS) in Primary Angle Closure and Primary Angle Closure Glaucoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2025; 19:483-506.

82. Luo J, Tan G, Thong KX, et al. Non-viral gene therapy in trabecular meshwork cells to prevent fibrosis in minimally invasive glaucoma surgery. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(11):2472.

83. Hübner L, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Weller JM. Ultrastructural analysis of explanted CyPass microstents and correlation with clinical findings. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022;260(8) :2663–2673.

84. Qin M, Yu-Wai-Man C. Glaucoma: Novel antifibrotic therapeutics for the trabecular meshwork. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;954:175882.

85. Dave B, Patel M, Suresh S, Ginjupalli M, et al. Wound Modulations in Glaucoma Surgery: A Systematic Review. Bioengineering (Basel). 2024; 11(5):446.