Neuroinflammation in Major Depressive Disorder: Insights

The Role of Neuroinflammation and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Major Depressive Disorder

Sigrid Breit, MD1,2

- University Hospital of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

- Translational Research Center, University Hospital of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 June 2025

CITATION: Breit, S., 2025. The Role of Neuroinflammation and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Major Depressive Disorder. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(7). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6743

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6743

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Neuroinflammation plays a significant role in the pathophysiology and progression of major depressive disorder. Elevated levels of inflammatory markers are associated with treatment resistance to conventional antidepressants and poor prognosis. Targeting inflammation with alternative anti-inflammatory treatments might be a promising treatment strategy for patients suffering from depression with underlying immune dysfunction. The use of inflammatory biomarkers is very useful to identify patients with inflammatory abnormalities at risk to develop treatment resistance and to select the appropriate treatment option from the beginning. The aim of the present review is to elucidate the impact of neuroinflammation on the pathogenesis and progression of major depressive disorder. It provides insight into alternative therapies targeting inflammatory pathways, such as electroconvulsive therapy and ketamine, and illustrates the role of potential inflammatory biomarkers to improve prevention of treatment resistance and treatment strategies.

Keywords:

Major depressive disorder, neuroinflammation, treatment resistance, immune dysfunction, inflammatory biomarkers.

1. The role of inflammation in major depressive disorder

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a serious and multifactorial mental illness with a complex pathophysiology, involving immune dysfunction and inflammatory abnormalities. There is evidence that more than a third of patients suffering from MDD do not respond sufficiently to conventional antidepressants and become treatment resistant. Treatment resistant depression (TRD) goes along with increased depression severity, a significant impairment in functioning, higher rates of metabolic and psychiatric comorbidities, and suicidal behavior.

It is well established that MDD is often associated with elevated levels of peripheral inflammatory markers that might correlate with depression severity and treatment resistance.

There is evidence for central effects of peripheral inflammation through microglial activation. Microglia are resident immune cells of the brain and can be activated by stress, infection, and chronic systemic inflammation. Microglial activation leads to an overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, triggering the activation of the enzyme indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which stimulates the kynurenine pathway that represents the major route for tryptophan metabolism. Elevated levels of inflammation also lead to the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis (HPA-axis) that plays a crucial role in the stress response, stimulating an increased glucocorticoid release. These pathophysiological mechanisms might cause a dysregulation of serotonergic and noradrenergic systems and contribute to the pathogenesis of MDD.

Chronic activation of the HPA-axis and consistently high cortisol concentrations might also have metabolic side effects, including increased appetite and insulin resistance, contributing to the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D).

A diverse profile of peripheral inflammatory markers and metabolic comorbidities might reflect a biological difference among patients suffering from MDD and lead to a different course of illness and treatment response. This subgroup of patients might be affected by an inflammatory cytokine-associated subtype of MDD with a higher risk of metabolic comorbidities and treatment resistance.

The effect of activated microglia and HPA-axis dysfunction on neurogenesis might be disruptive by triggering neuronal apoptosis and oxidative stress that results in neuroinflammation and cellular damage. Numerous neuroimaging studies demonstrated that chronic peripheral inflammation and alterations of the HPA-axis might be related to a reduction of cortical gray matter and subcortical volumes as well as impairments of white matter integrity within brain regions that are implicated in the pathophysiology of MDD. Mounting evidence revealed an association of MDD with reduced hippocampal volumes due to inflammatory abnormalities and immune dysfunction.

Therefore, neuroinflammation and immune dysfunction are strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of MDD, and particularly in the development of TRD.

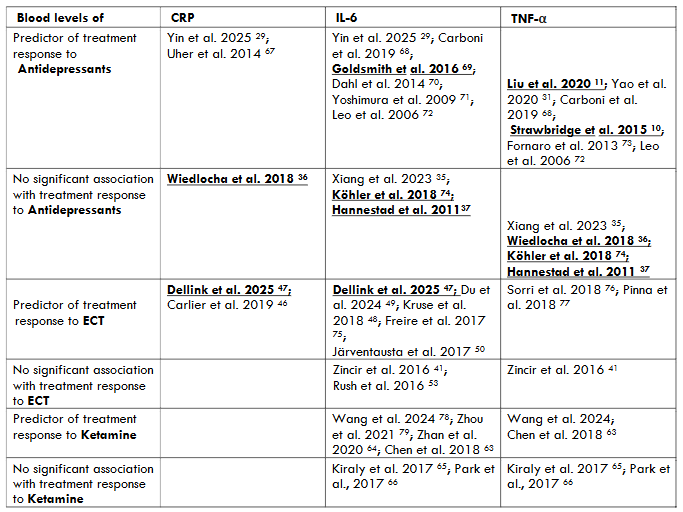

2. The use of inflammatory biomarkers in major depressive disorder

Given the strong relationship between inflammation and depression, the use of inflammatory biomarkers might be very promising to optimize depression treatment. They can help to distinguish between different subtypes of depression and identify patients who are at risk to develop treatment resistance. Inflammatory biomarkers are very useful to identify patients who might not respond to conventional antidepressants and make it possible to select the appropriate treatment option right from the start. A biomarker-guided treatment enables more personalized treatment strategies to tailor the therapy right to the individual profile of the patient for achieving the best possible treatment results.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are small signaling proteins, released by immune cells, such as macrophages and lymphocytes, that promote inflammation. Key pro-inflammatory cytokines include interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interferon (IFN)-γ. They are involved in cell signaling and play a crucial role in the regulation of the inflammatory response. They contribute to various immune processes and are very important for the balance of the immune system. The C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acute-phase protein synthesized primarily in the liver in response to inflammation. It is a valuable indicator of inflammation that is used in healthcare for identifying and monitoring inflammatory processes and can be utilized as a biomarker of inflammation to predict antidepressant response. It is a pragmatic and inexpensive option for biomarkers and is measured through commercial laboratories. The pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α are more specific and have a high potential to predict antidepressant response, especially in TRD. Moreover, IL-6 and TNF-α levels might be associated with depression severity and clinical improvement after treatment.

3. Inflammatory markers as predictors of antidepressant response

3.1 ANTIDEPRESSANTS

The most common prescribed antidepressants are selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that work by blocking the serotonin (5HT) transporter to increase the availability of serotonin in the synaptic cleft. They might have some anti-inflammatory properties, as the 5-HT system is also involved in inflammation regulation. Mounting evidence suggests that TNF-α is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine in the development and course of MDD. A major part of patients suffering from MDD have elevated TNF-α levels, and antidepressant treatments might lead to a decrease of TNF-α levels. A study that examined the relationship between plasma cytokine levels and response to SSRI treatment showed that a decrease of TNF-α levels was associated with an improvement of depressive symptoms after treatment with fluoxetine. A recent meta-analysis revealed that antidepressant treatment might lead to a significant reduction of TNF-α levels correlating with a clinical improvement of depressive symptoms and that responders had a significantly higher reduction of TNF-α levels than non-responders. Another recent study showed that 12 weeks of antidepressant treatment led to a significant improvement of depressive symptoms that was associated with a decrease in TNF-α levels. Thus, TNF-α might be a potential predictor of treatment response to commonly used antidepressants, such as SSRIs, in individuals with MDD.

There is evidence that tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) that interact with multiple neurotransmitter systems represent the class of antidepressants with the strongest anti-inflammatory properties by affecting various inflammatory pathways. Treatment with TCAs, such as amitriptyline and imipramine, leads to a modulation of toll-like receptor signaling as well as a reduction of oxidative stress and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-18. Therefore, TCAs have been proposed as a potential therapy for atherosclerosis in patients with MDD. However, there are studies indicating that antidepressants might not always have an impact on inflammatory blood marker levels and that changes in pro-inflammatory cytokine levels might be independent of antidepressant treatment outcome.

A recent study that investigated the effect of sertraline on cytokine levels in adolescents with first episode MDD indicated significantly higher levels of IL-1β and IL-6 as well as significantly lower TNF-α levels in adolescents with MDD than in healthy controls. After 8 weeks of treatment with sertraline, IL-1β and IL-6 levels decreased and TNF-α levels increased in adolescents with MDD compared to pre-treatment levels. There was only a weak correlation between IL-6 levels and depression severity and not enough support to consider it a potential predictor of treatment response. There was no significant association of baseline IL-1β and TNF-α levels with clinical response. A meta-analysis, comprising 32 studies, showed a significant decrease of IL-1β levels only after SSRI treatment and no significant effect of antidepressants on IL-2, TNF-α, IFN-γ and CRP levels. A meta-analysis, including 22 studies, revealed that SSRIs induced a decrease of IL-6 and TNF-α levels. However, the use of other antidepressants, though effective on depressive symptoms, had no impact on cytokine levels. A plenty of studies indicated a significant reduction of IL-6 levels due to antidepressant treatment and no significant correlation with depression severity.

3.2 ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a highly effective and fast-acting treatment for a multitude of mental illnesses, including severe depression and TRD. It is well known that ECT leads to a modulation of neurotransmitter levels, neurogenesis, and inflammatory cytokine levels. There is evidence from meta-analyses that ECT leads to a significant brain volume increase in limbic structures, such as the hippocampus and the amygdala, compared to pre-treatment values in patients with MDD. However, the relationship between these volumetric changes and clinical improvement of depressive symptoms following ECT needs further investigation.

Mounting evidence indicates that patients with MDD and elevated levels of peripheral inflammation are more likely not to respond to conventional antidepressants and benefit more from anti-inflammatory treatments, including ECT. Several studies have examined whether levels of inflammatory markers before treatment might predict response to ECT.

A very recent meta-analysis revealed that higher IL-6 and CRP baseline levels were significantly related to a greater improvement of depressive symptoms over the course of ECT. Kruse et al. (2018) indicated that higher IL-6 levels before ECT were associated with a greater reduction of depressive symptoms, identifying those depressed patients most likely to benefit from ECT. A recent study by Du et al. (2024) showed that ECT was effective in treating severe MDD in adolescents and that clinical improvement was associated with a decrease in IL-6 levels. There is evidence that ECT exerts an acute effect on inflammatory cytokine levels, particularly on IL-6 levels, leading to a rapid increase after the first sessions and a long-term effect inducing a decrease of IL-6 levels over the course of treatment in ECT responders. The long-term effect of ECT on IL-6 levels might be associated with treatment outcome, highlighting its potential role as a biomarker of ECT response in patients with MDD. However, there are studies indicating no relationship between changes in levels of inflammatory markers and of ECT outcome. A prospective study revealed no significant difference between IL-6 levels before and after ECT, and the alterations in other pro-inflammatory cytokine levels were not related to treatment response in patients with TRD. Furthermore, Rush et al. (2016) showed elevated baseline IL-6 levels that did not normalize after ECT completion and were not associated with clinical response in patients with MDD.

3.3 KETAMINE

The N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist ketamine is an anesthetic drug with analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antidepressant effects. Ketamine functions by blocking the transmission of glutamate at the NMDA receptor. Ketamine has diverse properties and might exert its therapeutic effects through anti-inflammatory actions on the HPA-axis and the kynurenine pathway. The administration of ketamine might also exert rapid antidepressant effects in patients with TRD by inducing a fast increase in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels that plays a crucial role in neuronal growth and represents an important marker of neuroplasticity.

Repeated ketamine administration has a modulating effect on hippocampal neurogenesis. A recent study showed that the treatment with ketamine led to a significant reduction of depressive symptoms, an increase of right hippocampal volume, and changes in inflammatory marker levels. Hippocampal volume increase was not associated with alterations in inflammatory markers, indicating a complex neurobiological mechanism of the antidepressant effect of ketamine.

A growing body of evidence indicates that ketamine induces a rapid reduction of depressive symptoms correlating with changes in inflammatory cytokine levels in patients with TRD. A double-blind randomized controlled trial showed that the reduction in TNF-α levels 40 minutes post-infusion correlated positively with a decrease in depressive symptoms. Moreover, a higher baseline inflammatory state might be associated with a better response to ketamine. A recent study by Zhan et al. (2020) revealed a downregulation of plenty of inflammatory markers during ketamine treatment and that changes in levels of IL-6 and IL-17A were associated with an improvement of depressive symptoms. However, there are also studies indicating no correlation between changes in inflammatory cytokine levels and clinical improvement after ketamine treatment, suggesting that inflammatory cytokines might be unreliable biomarkers of the antidepressant response to ketamine.

4. Conclusion

Immune dysregulation is a crucial contributing factor to the development of MDD. Inflammatory alterations might affect monoamine systems and brain structures, leading to neuroinflammation and long-term neuronal damage and dysfunction. Therefore, it is of great importance to identify patients with an inflammatory subtype of MDD early in the course of illness to prevent treatment resistance and chronification of depression. The use of inflammatory biomarkers is a highly beneficial method for selecting the appropriate treatment option and achieving a rapid treatment response.

As previously described, patients with MDD and elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines have a poorer response to conventional antidepressants. A potential biomarker of antidepressant response to conventional antidepressants, such as SSRIs, might be TNF-α. However, there are numerous studies denying the reliability of inflammatory biomarkers in predicting treatment response to antidepressants.

A growing body of evidence suggests that depressed patients with higher levels of inflammatory markers might benefit more from alternative treatments with an anti-inflammatory mechanism, such as ECT and ketamine. Both ECT and ketamine lead to a fast reduction of depressive symptoms that is associated with changes in cytokine levels in patients with TRD. Mounting evidence indicates that the most promising biomarker of antidepressant response to ECT and ketamine might be IL-6. Although there are a few studies questioning the reliability of pro-inflammatory cytokines as biomarkers of antidepressant response to ketamine and ECT, studies that support their potential as biomarkers of treatment response are clearly prevailing. There is a need for conducting further studies with higher sample sizes to examine the use of potential inflammatory biomarkers in the clinical assessment of patients with MDD to better guide treatment selection and obtain the best possible treatment outcome.

5. Conflicts of interest statement

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

6. Funding Statement

The author received no financial support.

7. Acknowledgements

None.

8. References

- Nemeroff CB. Prevalence and management of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68 Suppl 8:17-25.

- Baig-Ward KM, Jha MK, Trivedi MH. The Individual and Societal Burden of Treatment-Resistant Depression: An Overview. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2023;46(2):211-226.

- Reutfors J, Andersson TM, Tanskanen A, et al. Risk Factors for Suicide and Suicide Attempts Among Patients With Treatment-Resistant Depression: Nested Case-Control Study. Arch Suicide Res. 2021;25(3):424-438.

- Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):446-457.

- Liu Y, Ho RC, Mak A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Affect Disord. 2012;139(3):230-239.

- Haapakoski R, Mathieu J, Ebmeier KP, Alenius H, Kivimaki M. Cumulative meta-analysis of interleukins 6 and 1beta, tumour necrosis factor alpha and C-reactive protein in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;49:206-215.

- Kohler CA, Freitas TH, Maes M, et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(5):373-387.

- Yang C, Tiemessen KM, Bosker FJ, Wardenaar KJ, Lie J, Schoevers RA. Interleukin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and C-reactive protein profiles in melancholic and non-melancholic depression: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2018;111:58-68.

- Reus GZ, Manosso LM, Quevedo J, Carvalho AF. Major depressive disorder as a neuro-immune disorder: Origin, mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2023;155:105425.

- Strawbridge R, Arnone D, Danese A, Papadopoulos A, Herane Vives A, Cleare AJ. Inflammation and clinical response to treatment in depression: A meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(10):1532-1543.

- Liu JJ, Wei YB, Strawbridge R, et al. Peripheral cytokine levels and response to antidepressant treatment in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(2):339-350.

- Hassamal S. Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1130989.

- Streit WJ, Walter SA, Pennell NA. Reactive microgliosis. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;57(6):563-581.

- Sugama S, Takenouchi T, Fujita M, Conti B, Hashimoto M. Differential microglial activation between acute stress and lipopolysaccharide treatment. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;207(1-2):24-31.

- Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):46-56.

- Maes M, Leonard BE, Myint AM, Kubera M, Verkerk R. The new ‘5-HT’ hypothesis of depression: cell-mediated immune activation induces indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which leads to lower plasma tryptophan and an increased synthesis of detrimental tryptophan catabolites (TRYCATs), both of which contribute to the onset of depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(3):702-721.

- Haroon E, Raison CL, Miller AH. Psychoneuroimmunology meets neuropsychopharmacology: translational implications of the impact of inflammation on behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):137-162.

- Mulla A, Buckingham JC. Regulation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis by cytokines. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;13(4):503-521.

- Silverman MN, Pearce BD, Biron CA, Miller AH. Immune modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis during viral infection. Viral Immunol. 2005;18(1):41-78.

- Leonard BE. The HPA and immune axes in stress: the involvement of the serotonergic system. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20 Suppl 3:S302-306.

- Rutters F, Nieuwenhuizen AG, Lemmens SG, Born JM, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis functioning in relation to body fat distribution. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;72(6):738-743.

- Benedetti F, Poletti S, Vai B, et al. Higher baseline interleukin-1beta and TNF-alpha hamper antidepressant response in major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;42:35-44.

- Lei AA, Phang VWX, Lee YZ, et al. Chronic Stress-Associated Depressive Disorders: The Impact of HPA Axis Dysregulation and Neuroinflammation on the Hippocampus-A Mini Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(7).

- Bertollo AG, Mingoti MED, Ignacio ZM. Neurobiological mechanisms in the kynurenine pathway and major depressive disorder. Rev Neurosci. 2025;36(2):169-187.

- Han KM, Ham BJ. How Inflammation Affects the Brain in Depression: A Review of Functional and Structural MRI Studies. J Clin Neurol. 2021;17(4):503-515.

- MacQueen G, Frodl T. The hippocampus in major depression: evidence for the convergence of the bench and bedside in psychiatric research? Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(3):252-264.

- Troubat R, Barone P, Leman S, et al. Neuroinflammation and depression: A review. Eur J Neurosci. 2021;53(1):151-171.

- Yang C, Wardenaar KJ, Bosker FJ, Li J, Schoevers RA. Inflammatory markers and treatment outcome in treatment resistant depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2019;257:640-649.

- Yin M, Zhou H, Li J, et al. The change of inflammatory cytokines after antidepressant treatment and correlation with depressive symptoms. J Psychiatr Res. 2025;184:418-423.

- Ma K, Zhang H, Baloch Z. Pathogenetic and Therapeutic Applications of Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) in Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(5).

- Yao L, Pan L, Qian M, et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Variations in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder Before and After Antidepressant Treatment. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:518837.

- Amitai M, Taler M, Carmel M, et al. The Relationship Between Plasma Cytokine Levels and Response to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Treatment in Children and Adolescents with Depression and/or Anxiety Disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(8):727-732.

- Nobile B, Durand M, Olie E, et al. The Anti-inflammatory Effect of the Tricyclic Antidepressant Clomipramine and Its High Penetration in the Brain Might Be Useful to Prevent the Psychiatric Consequences of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:615695.

- Eslami M, Monemi M, Nazari MA, et al. The Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs): A Novel Therapeutic Approach to Atherosclerosis Pathophysiology. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2025;18(2).

- Xiang JJ, Hong S, Ran LY, et al. [Effect of Sertraline on Serum Cytokine Levels in Adolescents With First-Episode Major Depressive Disorder]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2023;54(2):310-315.

- Wiedlocha M, Marcinowicz P, Krupa R, et al. Effect of antidepressant treatment on peripheral inflammation markers – A meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;80(Pt C):217-226.

- Hannestad J, DellaGioia N, Bloch M. The effect of antidepressant medication treatment on serum levels of inflammatory cytokines: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(12):2452-2459.

- Jha MK, Trivedi MH. Personalized Antidepressant Selection and Pathway to Novel Treatments: Clinical Utility of Targeting Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(1).

- Greenberg RM, Kellner CH. Electroconvulsive therapy: a selected review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(4):268-281.

- Bahji A, Hawken ER, Sepehry AA, Cabrera CA, Vazquez G. ECT beyond unipolar major depression: systematic review and meta-analysis of electroconvulsive therapy in bipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;139(3):214-226.

- Zincir S, Ozturk P, Bilgen AE, Izci F, Yukselir C. Levels of serum immunomodulators and alterations with electroconvulsive therapy in treatment-resistant major depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1389-1396.

- Gay F, Romeo B, Martelli C, Benyamina A, Hamdani N. Cytokines changes associated with electroconvulsive therapy in patients with treatment-resistant depression: a Meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;297:113735.

- Wilkinson ST, Sanacora G, Bloch MH. Hippocampal volume changes following electroconvulsive therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2017;2(4):327-335.

- Takamiya A, Chung JK, Liang KC, Graff-Guerrero A, Mimura M, Kishimoto T. Effect of electroconvulsive therapy on hippocampal and amygdala volumes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(1):19-26.

- Miller AH, Raison CL. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(1):22-34.

- Carlier A, Berkhof JG, Rozing M, et al. Inflammation and remission in older patients with depression treated with electroconvulsive therapy; findings from the MODECT study(✰). J Affect Disord. 2019;256:509-516.

- Dellink A, Vanderhaegen G, Coppens V, et al. Inflammatory markers associated with electroconvulsive therapy response in patients with depression: A meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2025;170:106060.

- Kruse JL, Congdon E, Olmstead R, et al. Inflammation and Improvement of Depression Following Electroconvulsive Therapy in Treatment-Resistant Depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(2).

- Du N, Wang Y, Geng D, et al. Effects of electroconvulsive therapy on inflammatory markers and depressive symptoms in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1447839.

- Jarventausta K, Sorri A, Kampman O, et al. Changes in interleukin-6 levels during electroconvulsive therapy may reflect the therapeutic response in major depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(1):87-92.

- Yrondi A, Sporer M, Peran P, Schmitt L, Arbus C, Sauvaget A. Electroconvulsive therapy, depression, the immune system and inflammation: A systematic review. Brain Stimul. 2018;11(1):29-51.

- Lombardi AL, Manfredi L, Conversi D. How does IL-6 change after combined treatment in MDD patients? A systematic review. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2023;27:100579.

- Rush G, O’Donovan A, Nagle L, et al. Alteration of immune markers in a group of melancholic depressed patients and their response to electroconvulsive therapy. J Affect Disord. 2016;205:60-68.

- Kopra E, Mondelli V, Pariante C, Nikkheslat N. Ketamine’s effect on inflammation and kynurenine pathway in depression: A systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2021;35(8):934-945.

- Sukhram SD, Yilmaz G, Gu J. Antidepressant Effect of Ketamine on Inflammation-Mediated Cytokine Dysregulation in Adults with Treatment-Resistant Depression: Rapid Systematic Review. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:1061274.

- Halaris A, Cook J. The Glutamatergic System in Treatment-Resistant Depression and Comparative Effectiveness of Ketamine and Esketamine: Role of Inflammation? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2023;1411:487-512.

- Jozwiak-Bebenista M, Sokolowska P, Wiktorowska-Owczarek A, Kowalczyk E, Sienkiewicz M. Ketamine – A New Antidepressant Drug with Anti-Inflammatory Properties. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2024;388(1):134-144.

- Johnston JN, Greenwald MS, Henter ID, et al. Inflammation, stress and depression: An exploration of ketamine’s therapeutic profile. Drug Discov Today. 2023;28(4):103518.

- Haile CN, Murrough JW, Iosifescu DV, et al. Plasma brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and response to ketamine in treatment-resistant depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(2):331-336.

- Li Y, Li F, Qin D, et al. The role of brain derived neurotrophic factor in central nervous system. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:986443.

- Clarke M, Razmjou S, Prowse N, et al. Ketamine modulates hippocampal neurogenesis and pro-inflammatory cytokines but not stressor induced neurochemical changes. Neuropharmacology. 2017;112(Pt A):210-220.

- Zhou YL, Wu FC, Wang CY, et al. Relationship between hippocampal volume and inflammatory markers following six infusions of ketamine in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:608-615.

- Chen MH, Li CT, Lin WC, et al. Rapid inflammation modulation and antidepressant efficacy of a low-dose ketamine infusion in treatment-resistant depression: A randomized, double-blind control study. Psychiatry Res. 2018;269:207-211.

- Zhan Y, Zhou Y, Zheng W, et al. Alterations of multiple peripheral inflammatory cytokine levels after repeated ketamine infusions in major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):246.

- Kiraly DD, Horn SR, Van Dam NT, et al. Altered peripheral immune profiles in treatment-resistant depression: response to ketamine and prediction of treatment outcome. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(3):e1065.

- Park M, Newman LE, Gold PW, et al. Change in cytokine levels is not associated with rapid antidepressant response to ketamine in treatment-resistant depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:113-118.

- Uher R, Tansey KE, Dew T, et al. An inflammatory biomarker as a differential predictor of outcome of depression treatment with escitalopram and nortriptyline. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(12):1278-1286.

- Carboni L, McCarthy DJ, Delafont B, et al. Biomarkers for response in major depression: comparing paroxetine and venlafaxine from two randomised placebo-controlled clinical studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):182.

- Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(12):1696-1709.

- Dahl J, Ormstad H, Aass HC, et al. The plasma levels of various cytokines are increased during ongoing depression and are reduced to normal levels after recovery. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;45:77-86.

- Yoshimura R, Hori H, Ikenouchi-Sugita A, Umene-Nakano W, Ueda N, Nakamura J. Higher plasma interleukin-6 (IL-6) level is associated with SSRI- or SNRI-refractory depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(4):722-726.

- Leo R, Di Lorenzo G, Tesauro M, et al. Association between enhanced soluble CD40 ligand and proinflammatory and prothrombotic states in major depressive disorder: pilot observations on the effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(11):1760-1766.

- Fornaro M, Rocchi G, Escelsior A, Contini P, Martino M. Might different cytokine trends in depressed patients receiving duloxetine indicate differential biological backgrounds. J Affect Disord. 2013;145(3):300-307.

- Kohler CA, Freitas TH, Stubbs B, et al. Peripheral Alterations in Cytokine and Chemokine Levels After Antidepressant Drug Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(5):4195-4206.

- Freire TFV, Rocha NSD, Fleck MPA. The association of electroconvulsive therapy to pharmacological treatment and its influence on cytokines. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;92:205-211.

- Sorri A, Jarventausta K, Kampman O, et al. Low tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels predict symptom reduction during electroconvulsive therapy in major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. 2018;8(4):e00933.

- Pinna M, Manchia M, Oppo R, et al. Clinical and biological predictors of response to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a review. Neurosci Lett. 2018;669:32-42.

- Wang Y, Yang Q, Chen C, Yao Y, Yuan X, Zhang K. Inflammatory cytokines, cortisol, and anhedonia in patients with treatment-resistant depression after consecutive infusions of low-dose esketamine. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci. 2024.

- Zhou Y, Wang C, Lan X, Li H, Chao Z, Ning Y. Plasma inflammatory cytokines and treatment-resistant depression with comorbid pain: improvement by ketamine. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18(1):200.

- Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):220-229.

- Rao WW, Zong QQ, Zhang JW, et al. Obesity increases the risk of depression in children and adolescents: Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;267:78-85.

- Grigolon RB, Brietzke E, Mansur RB, et al. Association between diabetes and mood disorders and the potential use of anti-hyperglycemic agents as antidepressants. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;95:109720.

- Meshkat S, Liu Y, Jung H, et al. Temporal associations of BMI and glucose parameters with depressive symptoms among US adults. Psychiatry Res. 2024;332:115709.

- Calabro P, Yeh ET. Obesity, inflammation, and vascular disease: the role of the adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Subcell Biochem. 2007;42:63-91.

- Shelton RC, Miller AH. Eating ourselves to death (and despair): the contribution of adiposity and inflammation to depression. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;91(4):275-299.

- Savchenko LG, Digtiar NI, Selikhova LG, et al. Liraglutide exerts an anti-inflammatory action in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Rom J Intern Med. 2019;57(3):233-240.

- Bendotti G, Montefusco L, Lunati ME, et al. The anti-inflammatory and immunological properties of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. Pharmacol Res. 2022;182:106320.

- Diz-Chaves Y, Mastoor Z, Spuch C, Gonzalez-Matias LC, Mallo F. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Activation in the Brain in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(17).

- Kim YK, Kim OY, Song J. Alleviation of Depression by Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Through the Regulation of Neuroinflammation, Neurotransmitters, Neurogenesis, and Synaptic Function. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1270.

- Mansur RB, Ahmed J, Cha DS, et al. Liraglutide promotes improvements in objective measures of cognitive dysfunction in individuals with mood disorders: A pilot, open-label study. J Affect Disord. 2017;207:114-120.

- Tham M, Chong TWH, Jenkins ZM, Castle DJ. The use of anti-obesity medications in people with mental illness as an adjunct to lifestyle interventions – Effectiveness, tolerability and impact on eating behaviours: A 52-week observational study. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2021;15(1):49-57.

- Chen X, Zhao P, Wang W, Guo L, Pan Q. The Antidepressant Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2024;32(1):117-127.

- Moulton CD, Pickup JC, Amiel SA, Winkley K, Ismail K. Investigating incretin-based therapies as a novel treatment for depression in type 2 diabetes: Findings from the South London Diabetes (SOUL-D) Study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2016;10(2):156-159.

- McLaughlin AP, Nikkheslat N, Hastings C, et al. The influence of comorbid depression and overweight status on peripheral inflammation and cortisol levels. Psychol Med. 2022;52(14):3289-3296.

- McElroy SL, Guerdjikova AI, Blom TJ, Mori N, Romo-Nava F. Liraglutide in Obese or Overweight Individuals With Stable Bipolar Disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2024;44(2):89-95.

- Breit S, Hubl D. The effect of GLP-1RAs on mental health and psychotropics-induced metabolic disorders: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2025;176:107415.