Parallel Processing in Problem-Solving: A New Perspective

On Problem-Solving as Parallel Processing in a Network with the Limited Number of Connections Between Neuron-Like Units

Pavel N. Prudkov1, Olga N. Rodina2

- Independent researcher, Israel

- Department of Psychology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russian Federation

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED 31 October 2024

CITATION Prudkov, PN., and Rodina, ON., 2024. On Problem-Solving as Parallel Processing in a Network with the Limited Number of Connections Between Neuron-Like Units. Medical Research Archives, [online] 12(10). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i10.5806

COPYRIGHT © 2024 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i10.5806

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Problem-solving is considered a sequential process, when one thought is a prerequisite for the next one. However, most mental processes are parallel. Based on assumptions that thinking can be considered processing information in a network of neuron-like units functioning in parallel, we hypothesized parallel processing always occurs in problem-solving. We suggest there are individual differences regarding the easiness of the emergence of task-related but supplementary thoughts that can be applied to elucidate how parallel processing influences problem-solving. A questionnaire on the emergence of supplementary thoughts was designed. It was hypothesized there may be positive correlation coefficients between scores on the questionnaire and scores on problem-solving tasks and the times taken to perform these tasks. A total of 700 freelancers participated in three experiments. Four tasks were used to characterize problem-solving. To study the relationship between parallel processing and processing speed the simple reaction time task was used. A short-term memory task was used to investigate the relationship between parallel processing and working memory. Cronbach’s alpha for the questionnaire was 0.683. All correlation coefficients between scores on the questionnaire and the variables derived from the problem-solving tasks were significant. A correlation coefficient between scores on the short-term memory task and scores on the questionnaire was insignificant. A partial correlation between reaction times and scores on the questionnaire was insignificant. There was a positive correlation between scores on the questionnaire and age. Thus, unlike other characteristics associated with flexibility in thinking, parallel processing is not deteriorated with age. An explanation for this fact is suggested.

Keywords: thinking, parallelism, parallel processing, network, neuron-like unit.

1. Introduction

Though solving a problem is a covert process, this procedure seems to be identical to all humans. There is an initial representation of the problem situation, that is replaced by another representation through a series of some operations. This new representation, in turn, is replaced by the next representation owing to new operations. This process continues until one of these representations matches the goal-state, that means the problem is solved. Thus, the procedure of solving a problem is usually considered sequential, when each intermediate representation is a prerequisite for the next one.

It is important to note that mental processes, as a rule, occur concurrently. Perception is an obvious example of this because human beings can see and hear at the same time. Pain, emotions, desires occur independently of the perception of objects in the surrounding world and of each other. In these cases, mental processes are carried out concurrently, since these processes are based on different systems that can function independently. A question raises about the possibility of parallel processes within one system that consists of similar, but not identical units.

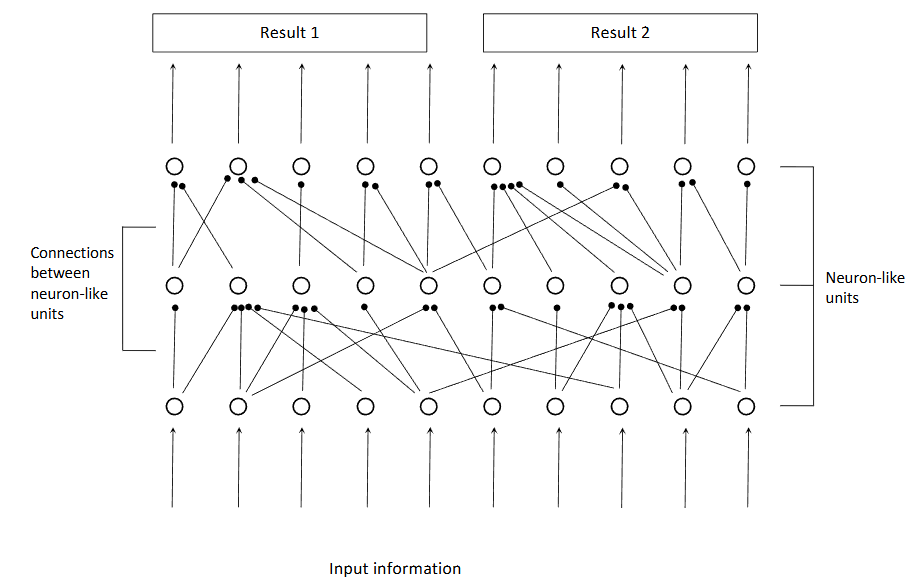

This question is important because some modern models of thinking describe solving a problem as the result of information processing in a network, that consists of similar units that imitate the functioning of neurons in the brain. Information processing by such units is carried out in parallel. In accordance with such models, the result of such a process is the achievement of a certain state by units of the network, that is manifested in the awareness of a representation or action. These models are often used to simulate various characteristics of thinking. It is reasonable to assume that the models based on the use of a network of neuron-like units do not reflect cognitive processes in its entirety, but the models are useful because they can become a heuristic basis for new approaches to thinking.

Similarly to the brain, each unit in a network of neuron-like units can be connected with several others, but not with all units in the network. This means that information is processed by different units concurrently but in different ways. With this method of processing, it is logical to assume there may be situations when the result of the activity of one group of units reaches a threshold of awareness, and after this the result of the activity of another group achieves the threshold independently.

If parallel processing is a real phenomenon, then its investigation, obviously, is a difficult problem, since the mechanism of parallel processing is unconscious and beyond deliberate control. It can be assumed, however, that similarly to other cognitive processes, there are individual differences in the generation of parallel processes. In other words, unexpected, but related to solving a specific problem, ideas may come to the mind of some individuals more often than to the mind of other individuals. If to design a questionnaire including statements that describe situations in which unexpected but task-related ideas come to mind and to ask the person to scale the frequency of occurrence of such situations, then the resulting score may reflect the person’s ability to generate parallel processes.

A suggestion that the mind of some people functions in a more parallel mode implies that their cognitive system may generate more thoughts regarding a problem and these thoughts may be more diverse. At the level of consciousness this means that such individuals acknowledge thoughts regarding a problem easier and more often hence they may solve the problem correctly but slowly. Therefore, it can be suggested that there may be positive correlation coefficients between scores on the questionnaire and scores on tasks being used in studies on problem-solving and the times taken to perform these tasks. One aim of our study was to explore such correlations.

There are several theories that hypothesize that parallel processes occur in thinking, such as dual processes theories or the theory of unconscious thought. To the best of our knowledge, all of such theories associate parallel processes with the existence of, at least, two systems that can function concurrently because they have different architectures. Therefore, the authors of such theories study qualitative differences between responses of participants in experiments. We posit that parallel processes emerge within one system, and hence we investigate individual differences in the quantitative characteristics of responses.

If parallel processing influences problem-solving, then there is an important question regarding its connection with other mechanisms that influence intelligence and problem-solving. Processing speed, estimated by various reaction time tasks, is one of such mechanisms. To investigate the relationship between parallel processing and processing speed we used the Simple Reaction Time task and calculated correlation coefficients between scores on the questionnaire on the ability to generate new thoughts and the variables derived from the Simple Reaction Time task. Working memory is another mechanism that influences problem-solving and intelligence. We used a short-term memory task and calculated a correlation coefficient between the outcome of the task and scores on the questionnaire on the ability to generate new thoughts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 PARTICIPANTS

Our study included three similar experiments. All participants in these experiments were recruited via Advego.ru, a Russian crowdsourcing system. The participants were paid US$0.8 for their work. The experiments were approved by the ethical committee of Lomonosov State University and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

All experimental sessions were run online. The procedure of the experimentation was fully automated. Information on the ongoing experiment was added to Advego’s list of active tasks and the task became available for all users of Advego. The design of Advego assured that each participant took part in the experimental session only once. There was no constraint on the duration of the experimental session.

A total of 215 participants (M age = 29.9 years (13-57); 112 females) took part in the first experiment. The six tasks presented to these participants are described in the Methods section below. A total of 205 participants (M age = 28.8 years (14-64); 119 females) took part in the second experiment. Another task was added to the list of tasks presented to the participants in the second experiment. A total of 280 participants (M age = 27.15 years (13-56); 176 females) took part in the third experiment. One task was added to the list of tasks presented to the participants in this experiment. Since the demographics of the participants in all experiments were similar, we combined all data together. In sum, 700 participants (M age = 28.45 years (13-64); 407 females) took part in the study.

2.2 MATERIALS

To evaluate the possibility of the emergence of supplementary ideas associated with the solution of a problem we worked out the Problem-Related Supplementary Thoughts Questionnaire (PRSTQ, hereinafter) that includes the following nine items:

- I think I am more likely than other people to have solutions to a problem coming to my mind on their own.

- If I have found a way to solve a problem, it is unlikely that any other ways of the solution will occur to me (reversed).

- It is quite possible that after I have already solved the problem, more ways of solving it might occur to me.

- Sometimes, new ideas might occur to me even when I am not solving the problem.

- Sometimes I put off the final solution to a problem as more ways of solving it still might occur to me.

- Sometimes, almost simultaneously, several ways to solve a problem can come into my head.

- It is hardly the thing with me that new ways of solving a problem suddenly come to my mind (reversed).

- If I keep thinking about a problem, a variety of ways to solve it might come to my mind.

- Sometimes a solution to a problem would come to me at the most unexpected time and in unexpected places: while sleeping, waking up, on a walk, etc.

A participant rated to what extent the item characterizes his/her. Responses were given on the following 5-point Likert scale:

- 1. = extremely uncharacteristic of me (not like me at all);

- 2. = partially uncharacteristic of me;

- 3. = neutral;

- 4. = partially characteristic of me;

- 5. = extremely characteristic of me (very similar to me).

The items of the questionnaire may lead to an assumption that the questionnaire is aimed at studying insight, that is a suddenly emerging solution to the problem. Indeed, since a person is not aware of the mechanism invoking insight, insight can be considered to be the consequence of some hidden process which is parallel to the process that occupies the focus of consciousness. However, the researchers of insight consider insight a rare phenomenon, but we believe that parallel information processing is always involved in thinking. Accordingly, the statements of the questionnaire only characterize the frequency of the emergence of new and unexpected thoughts associated with solving a problem. The items do not describe the situations in which those ideas arise, nor they evaluate its usefulness for finding a solution, nor they characterize emotions that accompany its appearance. The investigation of the relationship between parallel processing and conventional insight is beyond the scope of this paper.

We do not consider the questionnaire to be a full-fledged psychometric scale but assume that the questionnaire may be useful to estimate the possibility of the generation of task-related, supplementary thoughts.

If the PRSTQ scale is reliable then it is reasonable to suggest that a causal mechanism underpins responses of participants to the items. We designate this hypothetical mechanism the generator of task-related supplementary thoughts (GTRST, hereinafter). We do not suggest a prior that GTRST necessarily corresponds to a mechanism that processes information automatically and concurrently, GTRST may correspond to a deliberate, serial activity, theoretically.

Four tasks were used to examine correlations between responses to PRSTQ and the variables derived from problem-solving tasks. One task was the Russian version of the expanded version of the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT, hereinafter) by Toplak, West, Stanovich including seven problems. This task may be characterized as numerical and dual-processes are involved in the solution of these problems.

The second task was the Numerical Test (NT, hereinafter). This test included seven sequences that were borrowed from the Russian version of Eysenck’s Numerical Test. For example, the following sequence was used: 7 13 24 45 ?. The right response is 86. The aim of a participant was to continue the numerical series. The order of the presentation of the sequences was identical for all participants. This task can be characterized as numerical and related to fluid intelligence.

A common characteristic of these two tasks is that the tasks are complex. Indeed, to solve a CRT problem or a numerical sequence a participant should analyze the conditions, propose some hypotheses, test it through calculations, suggest new hypotheses, if necessary, etc. In other words, the procedure of solving such problems generates many thoughts. Although, we assume that GTRST corresponds to an automatic process, however the PRSTQ scale may be considered a measure of a metacognitive ability to monitor and evaluate own thoughts. It can be suggested that some people really delay the response to a problem because they experienced to monitor their thoughts continuously and hence, they believe that new ideas may come to mind yet. On the other hand, other people do not postpone the response because they do not expect novel thoughts. As a result, a significant correlation between the PRSTQ scale and, for example, CRT may reflect individual differences in this metacognitive ability rather than those in parallel processing.

To reduce a possible effect of the metacognitive ability we added two tasks that possibly generate fewer thoughts. One task was the Comparison of Two Words task in which 60 pairs of nouns were presented. For each pair it was necessary to mention whether both nouns designated animate objects, inanimate objects, or one noun designated an animate object and the other one did an inanimate object by selecting a position in the menu. There were 20 pairs for each selection. The order of presentation was randomized but identical for all participants. The pairs were prepared by the authors. The pairs were constructed so that the comparison of the nouns in each pair was not difficult. This task can be characterized as verbal and related to crystallized intelligence.

The other “easy” task was the Visual Search task. A string of 19 Russian letters was presented along with a probe letter, which was situated separately, for example: ЦШНДЭЪЬОЛЫЧАИКЩЯМХС ____П. The aim of a participant was to mention whether the probe letter was among the letters of the string by selecting a position in the menu. A total of 60 strings was presented, in 30 strings a probe letter was among the letters of the strings and it was absent in 30 other strings. The order of presentations was randomized but identical for all participants. This task can be characterized as verbal and spatial.

For all tasks all items were presented one at a time. There was no interval between the presentations of consecutive items. The number of the correct responses was considered the score on a task. The time taken to perform a task was considered the response time.

The following version of the Simple Reaction Time task was used: participants pressed on a button when they saw the symbol “A” on the display which appeared randomly in an interval from 1000 to 4000 milliseconds. There were five training probes and 40 test probes. If a participant pressed on the button prior to the appearance of the symbol such a response was ignored and another probe was presented until 40 probes were achieved. A mean and a standard deviation were calculated on the basis of 40 probes. Error rates were also calculated.

There are strong interconnections between working memory and short-term memory and some researchers even suggest that these systems are really the same ones. Therefore, we used a digit short-term memory task to evaluate the effects of working memory. The sequences including 7, 8, or 9 digits separated by a blank were presented for an interval of time being equal to 150*(the number of digits in the sequence) milliseconds. Immediately after this a probe digit was presented and the participant responded whether the probe digit was in the sequence by selecting a position in the menu. The performance on this task is obviously determined by attention and short-term memory. An average visual attention span is about five units. On the other hand, an average digit short-term memory span is greater than five digits but less than nine digits. The idea underlying this task is that the number of correct responses on the nine-digit-sequences might be less than that on the shorter sequences although there might not be such difference between the responses on the short sequences. If experimental data confirm this suggestion, then this task really reflects short-term memory rather than attention because attention should result in a steady decrease in correct responses. Therefore, a certain parameter for example, the total number of correct responses can be considered a measure of this sort of memory. One may say that such a measure may underestimate the digit short-term memory span of some individuals because they can memorize greater than nine digits. Yet, our research is correlational therefore this limitation should not affect our results. Sixteen sequences of each length were presented, in eight sequences the probe digit was among the digits in the sequence and the probe digit was absent in the other sequences. All of 48 sequences were present in a random but identical order for all participants. This task is designated the Short-Term Memory task hereinafter.

One may say that it is preferable to use conventional tasks for assessing working memory. However, all such tasks are designed as follows: first, one type of stimuli is presented and such stimuli must be memorized, then another type of stimuli is presented and certain operations with these stimuli must be performed. After that, it is necessary to reproduce the memorized material. This is a complex task, and preliminary training is necessary until the participant achieves the sufficient understanding and effective performance of such a task. Training is easy to manage in the laboratory under the supervision of the experimenter, who can assess the performance of the participant easily. In a fully automated experiment, the only assessment of effectiveness can be the achievement of some formal criterion, which can be a long and monotonous process. Since the motivation of participants was not high, it was important to avoid monotony and uniformity. It is for these reasons that a short-term memory task was used, which does not require long training.

The following tasks were presented to participants in the first experiment: PRSTQ, the Comparison of two words task, the Visual Search task, the Numerical Test, the Cognitive Reflection Test. The order of the tasks corresponds to the order of its presentation to participants. There was no interval between the tasks. The Simple Reaction Time task was added to the list in the second experiment. This task was presented after PRSTQ. The Short-term Memory task was added in the third experiment. This task was presented after the Simple Reaction Time task. As a result, 700 participants performed all tasks excluding the Simple Reaction Time task and the Short-term Memory task. 475 participants performed the Simple Reaction Time task and 280 participants did the Short-term Memory task.

3. Results

All participants performed PRSTQ and problem-solving tasks. 465 participants performed the Simple Reaction Time task. 280 participants performed the Short-term Memory task. Missing data were excluded from the analyses.

Cronbach’s alpha for the Task-Related Supplementary Thoughts Questionnaire scale was 0.683. This corresponds to a reliable scale therefore the sum of the rates on the nine items can be used as a score on this questionnaire. An average score was 32.94 (SD=5.497). An average score per item was 3.66, this number is higher than 3 that corresponds to the “neutral” rate of the items hence the phenomena described by the items really occurred in the thinking of participants.

An average number of correct responses to the seven-digit-sequences in the Short-Term Memory task was 12.91. An average number of correct responses to the eight-digit-sequences was 12.93. Obviously, there was no difference between these scores, t(279)=0.22, p=0.825. An average number of correct responses to the nine-digit-sequences was 11.89. This score distinguishes significantly from the other scores, t(279)=8.13, p=0.00 and t(279)=8.14, p=0.00. These results are consisted with our assumption that this task activates some mechanisms associated with short-term and, probably, working memory. All scores on the sequences were correlated with each other positively therefore the total number of correct responses was used as a score on the Short-Term Memory task.

A median response time for the Comparison task was 4.86 seconds per pair of nouns. A median response time for the Visual Search task was 4.77 seconds per string. On the other hands, a median response time per problem for CRT and NT was 39.07 and 36 seconds, respectively. These results imply that the Comparison task and the Visual Search task are, in fact, “fast” tasks and its performance may generate fewer thoughts per item than the performance of the “slow” tasks. A median reaction time was 0.548 seconds. A median standard deviation was 0.575 seconds and a median of error rates was 0 errors. All correlations between scores were positive and therefore a composite score was calculated as a sum of four z-standardized scores. A composite time of the performance of the four tasks was also calculated.

Correlation coefficients between PRSTQ scores, simple reaction times, Short-term Memory task scores, and the results of four tasks are presented in Table 1. Since PRSTQ scores, simple reaction times, and Short-term Memory task scores had non-normal distributions (K-S d=0.0895, p<0.01, K-S d=0. 1089, p<0.01, K-S d=0. 104, p<0.01), Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated.

| PRSTQ scores (n=700) | Reaction Times (n=465) | Short-term Memory scores (n=280) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response times, Comparison of Two Words task | 0.173**** | 0.120** | 0.107 |

| Scores, Comparison of Two Words task | 0.173**** | -0.060 | 0.268**** |

| Response times, Visual Search task | 0.208**** | 0.155*** | 0.088 |

| Scores, Visual Search task | 0.283**** | -0.002 | 0.303**** |

| Response times, Numerical Test | 0.275**** | -0.048 | 0.267**** |

| Scores, Numerical Test | 0.174**** | -0.193**** | 0.278**** |

| Response times, CRT | 0.236**** | -0.032 | 0.197*** |

| Scores, CRT | 0.126*** | -0.068 | 0.057 |

| Composite performance times | 0.256**** | 0.023 | 0.224*** |

| Composite scores | 0.261**** | -0.174**** | 0.321**** |

*-p<0.05; ** -p<0.01, ***- p<0.001; **** -p<0.0001

Significant correlation coefficients between simple reaction times and times to complete the easy tasks are obviously a reflection of the fact that, since the easy tasks were performed quickly, the duration of its performance replicates individual differences in simple reaction times. Reaction times correlate negatively with scores on all tasks and significantly with the composite scores. Negative correlations between simple reaction times and general cognitive ability were obtained in many studies. Scores on the Short-term Memory task are significantly correlated with most of the variables derived from the problem-solving tasks including the fast, verbal tasks. This means that the Short-Term memory task is the valid measure of working memory.

There are significant correlations between PRSTQ scores and the variables derived from the fast tasks. These correlations are similar to the correlation coefficients between PRSTQ scores and the results of performing more difficult tasks. We suggest this means that PRSTQ scores reflect the functioning of unconscious, automatic processes rather than the metacognitive strategies of participants. It is unlikely that the performance of the simple tasks could be accompanied by insights, therefore it can be considered that PRSTQ scores characterize mechanisms that are distinctive from mechanisms underpinning conventional insights.

| Short-term Memory scores (n=280) | Reaction times (n=465) | Standard deviations (n=465) | Error rates (n=465) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRSTQ scores | 0.097 | -0.093* | -0.128** | -0.202*** |

* – p <0.05; ** – p <0.01; *** – p < 0.001

Table 2 shows that the correlation coefficient between PRSTQ scores and Short-term Memory scores is not significant and all correlation coefficients associated with the Simple Reaction Time task are significant. However, if to calculate partial correlations between PRSTQ scores and reaction times and standard deviations then a partial correlation between PRSTQ scores and reaction times becomes insignificant (0.058, p=0.2) but a partial correlation between PRSTQ scores and standard deviations stays significant (-0.11, p=0.016). Since a correlation coefficient between average reaction times and standard deviations is very high, r = 0.98, to reduce the effects of multicollinearity we used ridge regression for the calculation of partial correlations. The variance inflation factor (VIF) is usually considered a characteristic of multicollinearity. If VIF calculated for an independent variable is greater than five then the multicollinearity of the variable is high. All VIFs computed in our analyses were less than five. Also, to normalize reaction times and standard deviations, for the calculation of partial calculations these variables were log10 transformed.

As PRSTQ scores increase, all parameters associated with the Simple Reaction Time task decrease. This is another piece of evidence favoring a notion that the Problem-Related Supplementary Thoughts Questionnaire reflects more fundamental mechanisms than the use of metacognitive strategies and processes associated with the emergence of insight.

Females scored on TRSTQ marginally higher than males (33.31 and 32.41 on average, p=0.037, d=0.161). However, there were other differences between the genders in the study because females scored higher on the composite scores (0.273 versus -0.463, t(669)=3.25, p=0.0011, d=0.286). It is reasonable to suggest that the mechanisms underpinning responses to the PRSTQ scale may be slightly interconnected with the mechanisms underlying responses to other variables therefore gender differences on these variables may result in gender differences on the PRSTQ scale. To examine this suggestion, we computed the difference between the genders using the composite scores as a covariant. In this case, the difference between the genders became insignificant (F (1, 697) =1.81, p=0.179). It is reasonable to assume that there is no difference between males and females on the PRSTQ scale for the entire population.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients between age and PRSTQ scores, short-term memory scores and the variables obtained from the Simple Reaction Time task are presented in Table 3.

| PRSTQ scores (n=700) | Short-term Memory Scores (n=280) | Reaction times (n=465) | Standard deviations (n=465) | Error rates (n=465) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.053 | -0.101 | 0.215*** | 0.182*** | 0.042 |

*** – p<0.001

Table 3 shows that a correlation coefficient between PRSTQ scores and age was positive, although not significant. This result is absolutely unexpected because, according to numerous studies, characteristics associated with the dynamism and variability of thinking (reaction time, working memory, fluid intelligence) tend to worsen with age. Also, in our experimentation the age of participants is negatively correlated with working memory and positively and significantly correlated with reaction times, in other words these parameters are deteriorated over age.

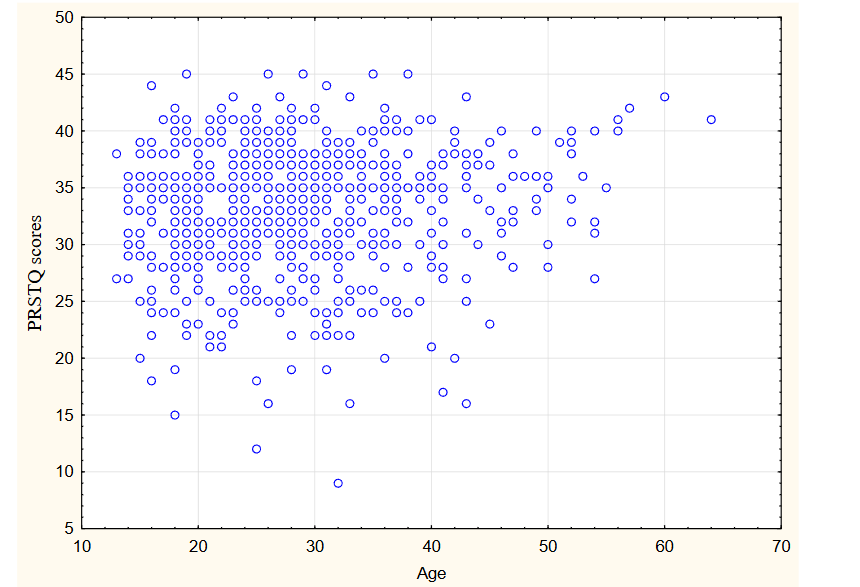

It is important to note that if to calculate partial correlations between age and reaction times and standard deviations then a partial correlation between PRSTQ scores and average reaction times is significant (0.1, p=0.03) but the second partial correlation is not significant (-0.013, p=0.72). Both PRSTQ scores and standard deviations, error rates are stable over age, this is another piece of evidence that favors a notion that GTRST influences the dispersion of reaction times and error rates. The relationship between age and the PRSTQ scores is presented in Figure 2.

Looking at Figure 2, it is not difficult to see that under 45 years of age the number of participants who scored on the PRSTQ scale high is approximately equal to the number of those who scored low. However, after 45 years of age those who scored high, prevail.

4. Discussion

The process of solving a problem is usually considered serial and conscious, when each intermediate representation, thought is a prerequisite for the next one until one of these representations matches the goal-state. However, numerous empirical facts demonstrate that sometimes some ideas regarding a problem come to the mind when the problem is absolutely beyond the focus of consciousness. Such facts are the basis for various theories that posit two systems may be involved in problem-solving in parallel because the systems have different architectures. It is usually suggested that one system is rather automatic and associative and the other system is rational, and reflective.

On the basis of a heuristic idea that thinking can be understood as processing information in a network of neuron-like units that function concurrently, we hypothesize that parallel information processing is always involved in problem-solving. Thus, the main distinction of our approach from other theories which assume the existence of parallel processing is that we posit parallel processing is possible within one system with slightly different units. To examine this hypothesis, we designated a questionnaire on the possibility of the emergence of supplementary thoughts associated with the problem and calculated correlations between scores on the questionnaire and the variables derived from four problem-solving tasks.

The results obtained in our study cannot be explained on the basis that the generator of task-related supplementary thoughts reflects the use of metacognitive strategies and/or some mechanisms invoking conventional insight. The results do not seem entirely sufficient to reject an assumption that the generator reflects a sequential process however, the items of the questionnaire focus on the sudden and uncontrollable appearance of novel ideas and the emergence of new ideas in this way is unlikely to correspond to a sequential process.

As a result, we suggest that the generator corresponds to parallel processing. We believe that our results confirm the hypothesis that parallel information processing occurs in problem-solving. Although solving a problem seems to be a serial process when one idea, representation invokes a subsequent one, in reality several thoughts are formed simultaneously. The formation of several thoughts starts with the beginning of solving the problem.

It is important to note that our approach does not contradict the suggestion that in some situations parallel processing may result from the activation of several systems with different architectures. Indeed, despite different architectures such systems possibly can be understood as networks with the limited number of connections between units.

PRSTQ scores do not correlate with Short-term Memory scores and, unlike working memory, PRSTQ scores are not worsened over age. The same conclusions are correct for processing speed. This means that parallel processing is based on mechanisms that are distinctive from mechanisms underlying working memory and processing speed.

The Simple Reaction Time task seems a primitive, practically automatic action, however, the situation is more complex. Indeed, in this task a participant is instructed to press on the button as soon as possible when she/he sees the stimulus. This means the participant must maintain a high level of attentiveness and vigilance however avoiding pressing on the button when the stimulus is absent. On the other hand, the participant must immediately press on the button when the stimulus is present. It can be hypothesized that the instruction launches two parallel processes. One process aims to inhibit pressing on the button, while the other process aims to activate such an action. These processes, obviously, interfere with each other. It is logical to assume that the stronger interference between these processes, the greater dispersion in reaction times and the higher error rates. The negative correlations between PRSTQ scores and standard deviations and error rates imply these processes interfere less if an individual scores on PRSTQ high. It is reasonable to assume that high PRSTQ scores reflect not only a high level of generation of parallel processes but also a weak interference between parallel processes in problem-solving.

An important parameter that determines the possibility of parallel processes is the density of connections between the units of a network. Obviously, if these connections are dense, that is, if each unit in the network is connected with a large number of other units, then the probability of the emergence of separate groups of units that process information concurrently is low. However, if the connections are rare, then the probability of the emergence of several separate groups is considerably higher.

Several studies reveal that there is the decrease in the density of the white matter in the brain over age. The white matter is the axons of neurons, that is, connections between the cells. Consequently, the connections between neurons in the brain become weaker and less frequent over age. If parallel processes are inversely related to the density of connections, then an age-related decrease in density explains why scores on the PRSTQ scale are stable over age.

Figure 2 demonstrates that among the participants who were older 45 years, high scores on the PRSTQ scale prevailed. The participation in crowdsourcing requires a relatively high level of intelligence and good computer skills and since an average age in the sample was 27.83 years, 39 participants who were older 45 years probably estimated their intelligence and computer skills above average. Indeed, their median composite score was 0.822 and 641 participants not older than 45 years scored 0.1 only. A median PRSTQ score of the elder participants was 35 and the younger participants scored 34. However, a median reaction time of the younger participants was faster: 0.544 seconds versus 0.572 seconds and the younger participants scored higher on the Short-term Memory task: 39 versus 35. This implies that for some people, the high and stable level of parallel processing compensates for the age-related decrement in other cognitive mechanisms.

It is necessary to mention the limitations of our research. Four tasks were applied to study the relationship between parallel processing and problem-solving. It is possible that the use of other tasks may seriously change correlations between the variables derived from those tasks and PRSTQ scores. A short-term memory task was used to estimate working memory. However, it is possible that the task is not relevant for estimating working memory and a special working task is necessary to evaluate the relationship between parallel processing and working memory. The Simple Reaction Time task was used to evaluate processing speed. However, it is possible that this task reflects processing speed incompletely and other tasks for example, the multiple choices reaction time task should be more appropriate. In this case the correlations between the PRSTQ scale and the variables derived from such tasks may be distinctive from the correlations obtained in the current study. Recruiting participants at crowdsourcing systems may result in some biases. There was a bias in our sample regarding genders because males scored on the composite scores lower than females. Also, our participants were younger than the entire population. It is possible that parallel processing functions differently in the elderly.

5. Conclusions

Following a heuristic idea that thinking can be understood as processing information in a network of neuron-like units that function concurrently, we hypothesize that parallel information processing occurs in problem-solving. We believe that our research demonstrates the existence of parallel processing in problem-solving. It is demonstrated that the mechanism of parallel processing is distinctive from the mechanisms of working memory and processing speed. An explanation for the fact that unlike other characteristics associated with the dynamism and flexibility in thinking, parallel processing is not worsened with age is suggested.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Thomas M S, McClelland J L. Connectionist models of cognition. 2008; The Cambridge handbook of computational psychology: 23-58.

- Siew C S, Wulff DU, Beckage N M, Kenett YN. Cognitive network science: A review of research on cognition through the lens of network representations, processes, and dynamics. 2019; Complexity: doi.org/10.1155/2019/2108423

- French RM. The computational modeling of analogy-making. Trends in cognitive Sciences. 2002; 6(5): 200-205.

- Hélie S, Sun R. Incubation, insight, and creative problem solving: a unified theory and a connectionist model. Psychological review. 2010; 117(3): 994-1024.

- Stoianov IP, Zorzi M, Umilta C. A connectionist model of simple mental arithmetic. Proceedings of EuroCogSci. 2019; 03:313-318.

- Sloman SA. The empirical case for two systems of reasoning. Psychological Bulletin. 1996; 119: 3–22.

- Dijksterhuis A, Nordgren LF. A theory of unconscious thought. Perspectives on Psychological science. 2006; 1(2): 95-109.

- Kail R, Salthouse TA. Processing speed as a mental capacity. Acta psychologica. 1994;86(2-3): 199-225.

- Sheppard LD, Vernon PA. Intelligence and speed of information processing: A review of 50 years of research. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008; 44: 535−551.

- Conway AR, Getz SJ, Macnamara B, Engel de Abreu PMJ Working memory and intelligence. The Cambridge handbook of intelligence. 2011; 394- 418.

- Conway A R, Macnamara BN, de Abreu PME. Working memory and intelligence: An overview. Working Memory. 2013; 27-50.

- Danek A H, Williams J, Wiley J. Closing the gap: connecting sudden representational change to the subjective Aha! experience in insightful problem solving. Psychological research. 2018; 84: 111–119.

- Weisberg R W. Toward an integrated theory of insight in problem solving. Thinking& Reasoning. 2015; 21(1): 5-39.

- Rodina ON Prudkov PN. Testing of a Russian-language version of the Cognitive Reflection Test. Voprosy Psikhologii. 2019; (4): 155-162 (in Russian).

- Toplak M E, West R F, Stanovich K E. Assessing miserly information processing: An expansion of the Cognitive Reflection Test. Thinking & Reasoning. 2014; 20(2): 147-168.

- Pennycook G. A perspective on the theoretical foundation of dual-process models. Dual process theory. 2017; 2: 13-35.

- Eysenck HJ, Louk AN, Khorol IS. Check your IQ. 1972 (in Russian).

- Cowan N. What are the differences between long-term, short-term, and working memory? Progress in brain research. 2008; 169: 323-338.

- Aben B, Stapert S, Blokland A. About the distinction between working memory and short-term memory. Frontiers in psychology. 2012; 3: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00301

- Unsworth N, Engle RW. On the division of short-term and working memory: an examination of simple and complex span and their relation to higher order abilities. Psychological bulletin. 2007; 133(6): 1038-1066.

- Nadel L, Hardt O. Update on memory systems and processes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011; 36(1): 251-273.

- Frey A, Bosse ML. Perceptual span, visual span, and visual attention span: Three potential ways to quantify limits on visual processing during reading. Visual Cognition. 2018; 26(6): 412-429.

- Grégoire J, Van Der Linden M. Effect of age on forward and backward digit spans. Aging, neuropsychology, and cognition. 1997; 4(2): 140-149.

- Deary I, Der G, Ford G. Reaction times and intelligence differences: A population-based cohort study. Intelligence. 2001; 29: 389−399.

- Grudnik JL, Kranzler JH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between intelligence and inspection time. Intelligence. 2001; 29: 523−535.

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for behavioral sciences. 2013.

- O’Brien R M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality Quantity. 2007; 41 (5): doi:10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6

- Deary I J, Der G. Reaction time, age, and cognitive ability: Longitudinal findings from age 16 to 63 years in representative population samples. Aging, Neuropsychology, and cognition. 2005; 12(2): 187-215.

- Gregory T, Nettelbeck T, Howard S, and Wilson C. Inspection time: a biomarker for cognitive decline. Intelligence. 2008; 36: 664–671.

- Hester R L, Kinsella GJ, Ong BEN (2004). Effect of age on forward and backward span tasks. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS. 2004; 10(4): 475-481.

- Tucker-Drob EM, De la Fuente J, Köhncke Y, Brandmaier AM, Nyberg L, Lindenberger U. A strong dependency between changes in fluid and crystallized abilities in human cognitive aging. Science Advances. 2022; 8(5): eabj2422.

- Hadamard J. An essay on the psychology of invention in the mathematical field. 1954.

- Lubart TI. Models of the creative process: Past, present and future. Creativity research journal. 2001; 13(3-4): 295-308.

- Csikszentmihalyi M. The domain of creativity. Theories of Creativity. 1990: 190-212.

- Sloman SA. Two systems of reasoning. Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment. 2002; https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511808098.02

- Pennycook G, Fugelsang JA, Koehler DJ. What makes us think? A three-stage dual-process model of analytic engagement. Cognitive Psychology. 2015; 80: 34–72.

- Stephens RG, Dunn JC, Hayes BK (2018). Are there two processes in reasoning? The dimensionality of inductive and deductive inferences. Psychological Review. 2018; 125(2): 218–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000088

- Hogstrom LJ, Westlye LT, Walhovd KB, Fjell AM (2013). The structure of the cerebral cortex across adult life: age-related patterns of surface area, thickness, and gyrification. Cerebral cortex. 2013; 23(11): 2521-2530.

- McGinnis SM., Brickhouse M, Pascual B, Dickerson BC (2011). Age-related changes in the thickness of cortical zones in humans. Brain topography. 2011; 24(3-4): 279-291.

- Sele S, Liem F, Mérillat S, Jäncke L (2021). Age-related decline in the brain: a longitudinal study on inter-individual variability of cortical thickness, area, volume, and cognition. NeuroImage. 2021; 240: doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118370.