Preoperative POCUS in Hip and Femur Fracture Patients

A Narrative Review: The role of preoperative POCUS in patients with hip and femur fractures

Abstract

The application of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in clinical anesthesia practice is growing, particularly in the preoperative setting. This review discusses the growing use of POCUS beyond physical examination and the anesthesia techniques in patients scheduled to undergo repair of hip or femur fractures.

Keywords

- POCUS

- hip fractures

- femur fractures

- anesthesia

- preoperative care

Introduction

Hip and femur fractures are relatively common in elderly patients. In this population, it requires a strong force to break these bones, in the elderly, low-energy trauma can lead to proximal femur fractures. Especially in this population, these fractures are associated with increased mortality, having both short and long-term consequences. Early surgical fixation is associated with better outcomes. Benefits include lower morbidity and reduced risk of complications including pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, surgical infections as well as others. In addition, early repair leads to shorter hospital stays and costs.

There are several risk factors for hip and femur fractures, as mentioned including age, sex, and comorbidities. In this review, we explore the potential advantages of POCUS to avoid complications and improve safety and outcomes.

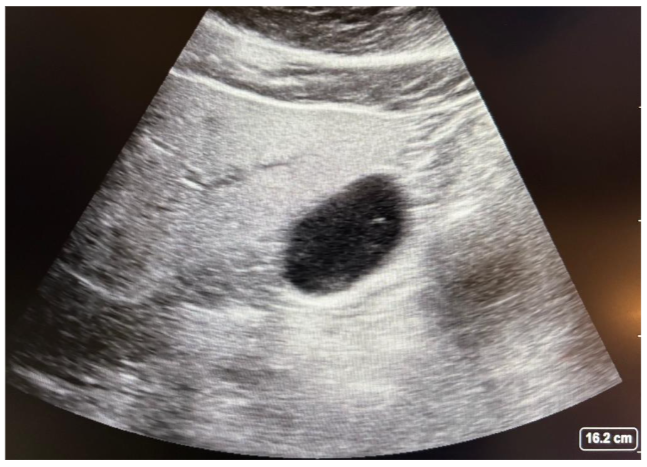

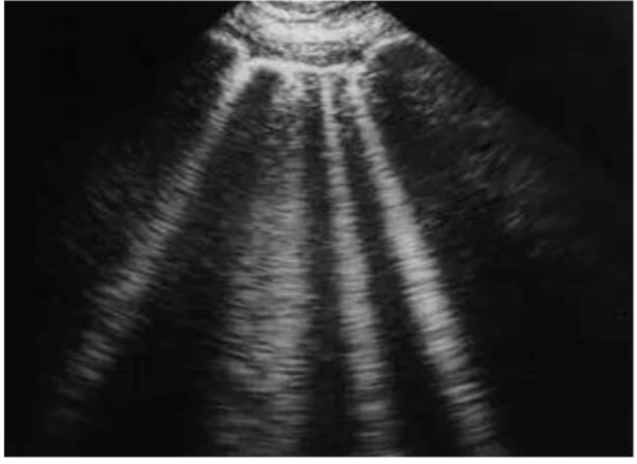

Gastric POCUS

There are some important limitations to consider when performing gastric POCUS in patients with hip and femur fractures. Specifically, it is imperative to confirm that the stomach is empty; it is important to assess the gastric contents in the right lateral decubitus position which may not be feasible in patients with a hip or femur fracture. The rationale is that in the right lateral decubitus position, gastric contents will displace to the atrium. This is the reason why an assessment in the supine position cannot determine if a patient has an empty stomach. Any time solid contents are visualized (frosted glass pattern), the patient is considered to have a high aspiration risk. This same applies to high volume aspiration, as shown in figure 2. In this situation, the anesthesiologist has to evaluate the patient for deep sedation or placing a supraglottic device.

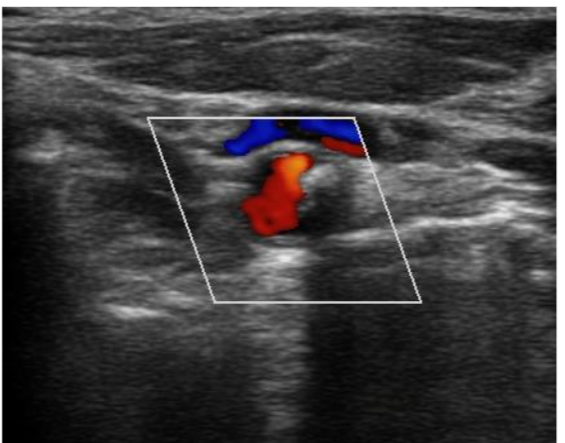

Carotid Arteries

Using ultrasound is a technique that can be used pre- and postoperatively to assess blood flow and vascular status in the central veins to help guide fluid management. In this situation, following the central venous catheterization, the use of a Doppler ultrasound can be beneficial.

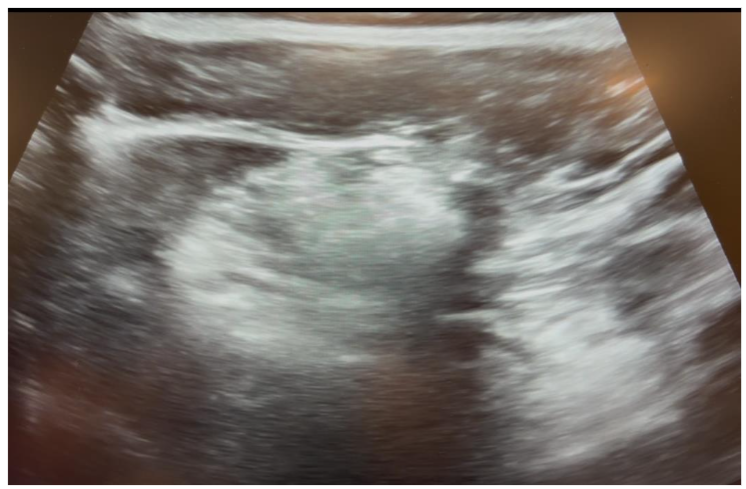

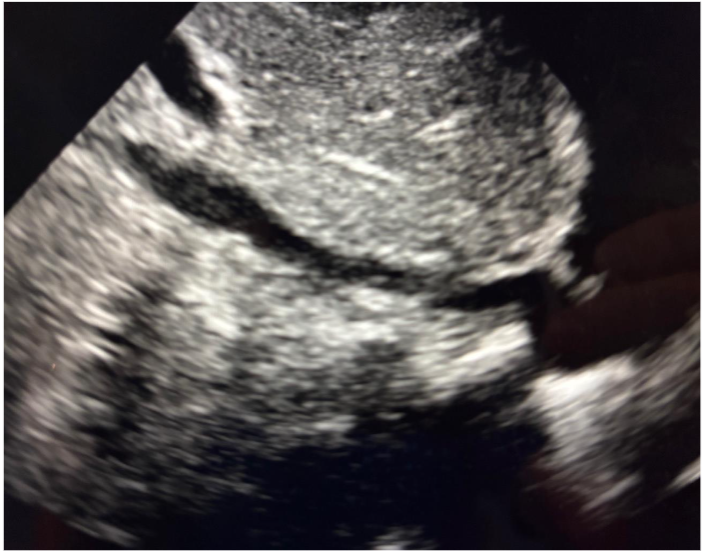

Lungs

Lung ultrasound is relatively easily done. The low-frequency curvilinear probe is preferred for deeper structures whilst the linear high-frequency shows better shallow structures like the pleura. The importance of lung ultrasound is often underestimated by anesthesiologists but it is widely accepted as a reliable tool for evaluating pulmonary status at the bedside.

Ultrasound findings in a normal lung include the presence of B-lines, A-lines, lung pulse, and B-lines. M-mode ultrasound can be used to assess the presence of “bar code” sign to “seashore sign.”

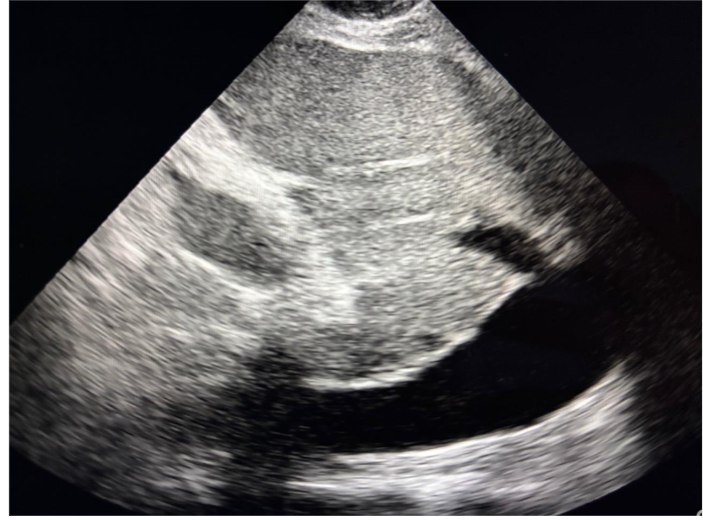

Inferior Vena Cava

Venous excess ultrasound (VeXUS) is a technique that can be used pre- and postoperatively to assess blood flow and vascular status in the central veins to help guide fluid management. In this situation, following the central venous catheterization, the use of a Doppler ultrasound can be beneficial.

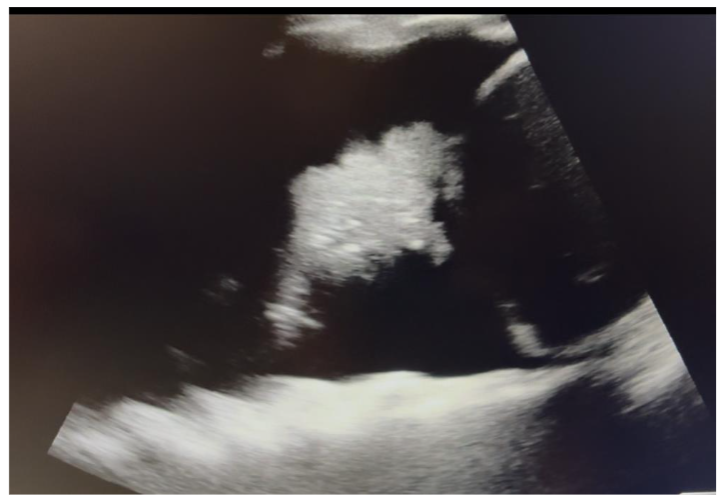

Cardiac

Arguably, the most useful modality of POCUS in patients that can prevent early surgery are hemodynamic instability, acute coronary syndrome, decompensated heart failure, coagulopathy, and interstitial lung disease.

Considering that the optimal timing from presentation to surgery is relatively short, it is common that anesthesiologists will encounter patients that do not have recent cardiac diagnostic testing or imaging. Cardiac POCUS provides an invaluable tool. It is noninvasive, performed at the bedside, and can rapidly provide very useful information to the anesthesiologist. It is important to emphasize that cardiac POCUS is focused on the assessment of ventricular function and is not intended to replace traditional diagnostic tools.

Conclusion

Hip fractures are a frequent and major public health concern for elderly patients. In this high-risk population, cardiopulmonary disease may be non-diagnosed or masked by other patient conditions. The preoperative evaluation of patients with hip or femur fractures traditionally involves a limited assessment. However, this is often not enough to provide the best care. The use of POCUS can be beneficial to guide decision making regarding aspiration risk and to better assess fluid status and cardiac function.

References

- Harvin JK, Malekzadeh T, Eder C, et al. Early femur fracture fixation is associated with a reduction in pulmonary complications and hospital charges – a plaque of experience with 1,376 displaced femur fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6):1442-8; discussion 1448-9. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182728966.

- Shelton C, White S. Anaesthesia for hip fracture repair. BJA 2002; 89(1): 10-16. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2002.02.001.

- Uppalapati T, Thornton J. Anesthesia Management of Hip Fracture Surgery in Elderly Patients. Anesth Analg. 2016;122(4):113-20. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000000953.

- Mariman S, Eimermacher AV, Burn DJ. Delayed gastric emptying in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2014;29:21-32. doi:10.1002/mds.25708.

- Wills AW, Roberts E, Beck JC, et al. Incidence of Parkinson’s disease in North America. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2022; 8(1): 37. doi:10.1038/s41531-022-00210-y.

- Benninger P, Rapp K, Maetzler W, et al. Risk for femoral fractures in Parkinson’s disease patients with and without severe functional impairment. PLoS One. 2016; 11(10): e0164901. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164901.

- Hsu K, Kusunoki H, Kanbara K, et al. A cardiac risk assessment tool for patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. BJA 2018; 121(4): 113-20. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2018.06.013.

- Nason KS. Nason KS. Anesthesiology for hip fracture repair. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(1): 126-30. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31826a3c3e.

- Huang J, Hamamoto M, et al. Simplified Algorithm for Perioperative Cardiovascular Management for Noncardiac Surgery. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021; 150(19): e466. doi:10.1161/CIR.00000000000001285.