Regenerative Endodontics: Advances and Clinical Protocols

Rooted in Regeneration: An Overview on Regenerative Endodontics

Dr. Farhan Iqbal Ariwala1, Dr. Maria Shabbir Calcuttawala2,

- Specialist Endodontist, Burjeel Hospital, Oman

- General Dentist and Implantologist, Mumbai

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 October 2025

CITATION: Ariwala, F., and Calcuttawala, MS., 2025. Rooted in Regeneration: An Overview on Regenerative Endodontics. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(10). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i10.6981

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i10.6981

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Regenerative endodontic procedures (REPs) are a relatively recent treatment option in dentistry. Although, the roots of its underlying principles can be traced to the early 1970s, the first clinical application did not take place until 2001. These procedures can help revolutionize the treatment of immature permanent teeth, where the development of the root has ceased due to the infection destroying the capabilities of the tooth to do so. The conventional treatment modality of apexification, simply involved the formation of a hard tissue barrier, upon which conventional obturation of the root canal system was performed. However, this method does not reinforce the structurally compromised root. In contrast, REPs not only eradicate infection but also promote continued root development, increasing both root length and dentinal wall thickness. Current clinical evidence supports a favourable prognosis for REPs, particularly in achieving disinfection. In cases of failure, the procedure can be repeated or alternative treatments such as apexification or conventional non-surgical root canal therapy may be employed, offering clinicians multiple management pathways, which can be presented to patients. This article reviews clinical considerations and recommended protocols, providing clinicians with comprehensive data to support implementation in practice.

Keywords

- Regenerative endodontics

- Immature permanent teeth

- Apexification

- Pulp-dentine complex

- Clinical protocols

Introduction

The foundation of regenerative endodontic procedures (REPs) dates back to the work of Nygaard-Ostby and Hjortdal in 1971, who intentionally induced bleeding from periapical tissues into a prepared root canal. They partially obturated the canal, leaving an apical void. These teeth were later extracted and histologically examined from a period of 9 days to 3 years, post obturation, to reveal a type of fibrous connective tissue and cellular cementum in the apical portion of the prepared canals. This was the first demonstrable instance for REPs.

Despite its long history, regenerative endodontics remains to be perceived by some physicians as a relatively recent innovation in clinical practice. In 2001, Iwaya et al. reported a clinical case of revascularization in an immature permanent tooth with apical periodontitis and a sinus tract, where root maturation and apical closure were observed months later. This term was changed to revitalization as not only blood vessels were regenerated, but an entire tissue. Since then, multiple case reports along with reviews have cemented the concept of ‘revitalization’/ ‘revascularization’/’regeneration’ as a viable treatment option for immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulp tissue. The limitations inherent with the traditional treatment modalities for immature permanent teeth, such as apexification, have introduced a requirement to not only eliminate infection, but also to restore tooth function and structures.

Regenerative endodontics could be defined as ‘biologically based procedures designed to replace damaged tooth structures, including dentine and root structures, along with the cells of the pulp-dentine complex’.

The traditional approach of treating immature permanent teeth was via the apexification procedure, where an apical hard barrier was formed using calcium hydroxide, or more recently with Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA). However, the main disadvantage of these procedures are that they only provide a mechanical barrier at the apex, without continued development of the roots, both in length and thickness. Thus, the overall mechanical strength of the tooth would remain compromised.

Promising results have been reported through various clinical trials and case reports, documenting continued root development, thickness of dentinal walls, and apical closure. These outcomes suggest that REPs may offer a more viable, long-term solution for preserving immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulp tissue. This approach has been considered as a ‘paradigm shift’ and is now considered the treatment of choice for immature permanent teeth, where the pulpal tissue is necrotised.

The term ‘regenerative endodontics’ was adopted by the American Association of Endodontics (AAE) in 2007 by incorporation of tissue engineering concepts as a treatment protocol. It utilizes the triad of tissue engineering, which are: stem cells, scaffolds and bioactive growth factors. The term ‘revitalization’ was adopted by the European Society of Endodontics (ESE) in 2016 via their position statement on the subject.

The goal of this article is to provide clinicians with robust evidence regarding the feasibility, clinical simplicity, and favourable prognosis associated with REPs, to facilitate their implementation in clinical practice. A detailed clinical protocol will be outlined, including relevant clinical factors, precautions, and potential adverse effects, to ensure easy access to all pertinent clinical data related to REPs.

Pulp pathogenesis

Understanding the pathogenesis of pulp disease is essential to selecting appropriate treatment modalities in clinical practice. A study examining the response of pulp and periapical tissues to deep carious lesions in immature permanent teeth found that irreversible pulp inflammation was accompanied by a significant reduction in cellularity at the apical papilla, as well as discontinuity or complete absence of Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath (HERS). In cases of pulpal necrosis, the apical papilla was entirely lost, and the pulp tissue was colonized by bacterial biofilms. These findings show that once an immature tooth undergoes necrosis, it no longer has the ability to continue its root formation.

The immune system in younger individuals is generally more robust than in older patients. Additionally, the larger apical foramen present in young permanent teeth allows for increased pulpal blood flow. This enhanced circulation plays an important role to the greater resilience of immature teeth, allowing them to better withstand traumatic injuries or deep carious lesions compared to mature teeth.

Clinical Protocol for Regenerative Endodontic Procedures

A wide variety of techniques and protocols have been described in the literature for regenerative endodontic procedures. According to a review on clinical protocols for Regenerative Endodontic Therapies (RETs), substantial variations exist across studies. Despite these differences, many protocols were still successful in achieving favourable clinical and radiographic outcomes, such as the resolution of clinical symptoms and apical periodontitis, as well as promoting increased thickness of canal walls and continued root development—though the latter two outcomes were achieved inconsistently.

To guide clinicians, the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) published “Clinical Considerations for a Regenerative Procedure,” providing a framework for the management of immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulp and/or apical periodontitis. However, the AAE emphasized that these considerations should be viewed as one of many evolving resources and encouraged clinicians to stay informed as new research emerges in this rapidly developing field.

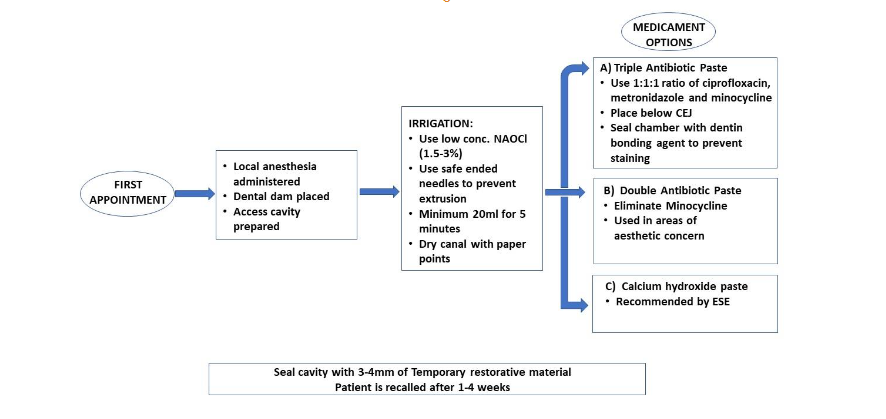

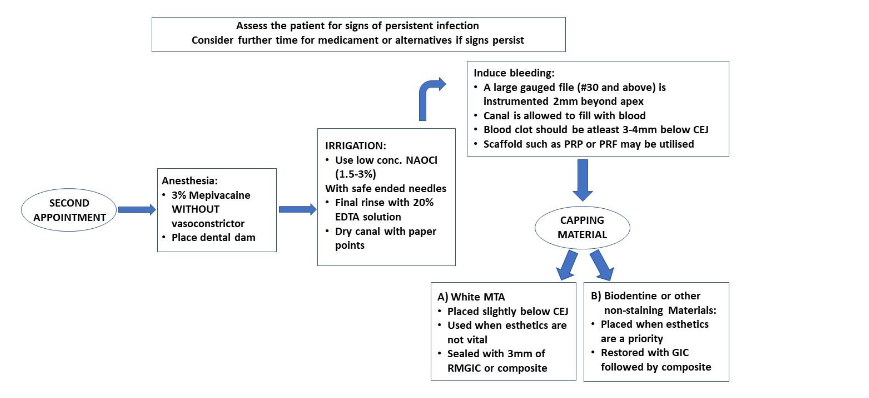

Standardizing protocols is essential not only for achieving consistent clinical outcomes, but also for ensuring uniformity in future research. An outline for RET procedures has been proposed by the authors and are presented in Table 1 and 2.

Clinical Considerations

The guiding principles of RETs need to be understood in order for a clinician to make an informed decision as to how to go about such procedures in their clinical practice. It is well known that each case possesses their own respective difficulties and circumstances, which require the clinician to modify their treatment procedure. Some important considerations have been listed below.

- SIZE OF APICAL DIAMETER

Bone, cementum, periodontal ligament, and even blood vessels cannot grow into the canal space because they are the products of osteoblasts, cementoblasts, periodontal ligament cells, and endothelial cells, respectively. All of these cells are located extra-radicularly, that is, beyond the apex of the tooth. The apical diameter of immature permanent teeth has been a major concern in RET. In a recent review article, it was shown that an apical diameter smaller than 1 mm achieved clinical success after regenerative endodontic treatment. However, it has been demonstrated that greater root maturation may be achieved in cases where the apical diameter is more than 1mm. Nevertheless, apical diameters of 0.5-1.0 mm attained the highest clinical success rate. - IMPORTANCE OF STEM CELLS

Stem cells play a central role in regenerative endodontics due to their unique ability to differentiate into specialized cell types required in the formation of the pulp-dentine complex. The primary stem cell types used in regenerative endodontics include Dental Pulp Stem Cells (DPSCs), Stem Cells from Apical Papilla (SCAPs), Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells (PDLSCs), and Dental Follicle Progenitor Cells (DFPCs). The presence of prior infection in the region where these stem cells reside could negatively affect the process of pulp tissue regeneration due to damage to these tissue forming cells. This is supported by the histological findings from animal studies and human case reports, where they showed that tissues formed in the root canal space of previously infected teeth were not that of the pulp-dentine complex, but of tissues related to the periodontal ligament such as bone, cementum and periodontal ligament. Therefore, there is a need for complete elimination of intra-radicular infection in order for pulp tissue regeneration to occur in RET. Each stem cell type has their own function, producing specific tissues. Dental pulp stem cells or DPSCs, for example, have been shown to have a high potential for odontogenic differentiation, in other words, making them useful for dentine regeneration in procedures like Indirect and Direct pulp capping. However, these cells are only viable in non-infected root canal systems. Stem Cells from Apical Papilla (SCAPs), on the other hand, are crucial for promoting root development in immature teeth with necrotic pulp, which is needed for RETs. - INFLUENCE OF GROWTH FACTORS

Growth factors are polypeptides produced by immuno-inflammatory and tissue cells, which are bound to the extracellular matrix. These signalling molecules regulate numerous cellular processes including survival, proliferation, migration, and differentiation. They usually have specific temporal and spatial expression during tissue regeneration and repair; that is, they function only during certain aspects of tissue repair, after which their beneficial effects cannot be utilised. In Regenerative Endodontic Therapy (RET), the choice of disinfection irrigants and intracanal medicaments can influence the release of growth factors from the dentine matrix. It has been demonstrated that various bioactive molecules are embedded in the dentine matrix and can be released upon demineralization. During RET, a dentine conditioning agent is used to liberate the entrapped biological molecules from the dentinal matrix before apical bleeding is evoked. Some of the important growth factors that have been seen to play an important role in REPs are Transformin Growth Factor (TGF-β1), fibroblast growth factors (FGF-2) and platelet derived growth factors (PDGF) which have been seen to enhance cell migration; PDGF and vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) which have been observed to control angiogenesis or formation of the tissue vasculature; TGF-β1, FGF2, VEGF and insulin-like growth factors which stimulate cell proliferation; Bone morphogenetic proteins and FGF2 that have been shown to promote dentinogenesis. - DISINFECTANT IRRIGANTS

The most commonly used irrigant in root canal therapy is Sodium Hypochlorite. It has been shown concentration of 5.25% sodium hypochlorite was able to eliminate single-species biofilm in 30 seconds. Sodium hypochlorite is considered as the gold standard for irrigants in conventional non-surgical root canal therapy. The AAE Clinical Considerations for a Regenerative Procedure recommends the use 1.5% sodium hypochlorite followed by 17% EDTA. This recommendation is mainly based on the studies that show the cytotoxic effect of sodium hypochlorite on survival of stem cells from the apical papilla in vitro rather than on killing of the intracanal bacteria in vivo. - CALCIUM HYDROXIDE AS AN INTRACANAL MEDICAMENT

Calcium hydroxide has been recommended as an intracanal medication in both non-surgical root canal therapy as well as RET because of its excellent antimicrobial properties. Calcium hydroxide has a high pH of 12.5-12.8, which is not a favourable environment for most bacteria to survive. A study comparing the effects of calcium hydroxide with that of TAP has shown that the attachment of human apical cells to root dentine is higher when treated with calcium hydroxide, however, this was an in vitro study. As calcium hydroxide has a long-proven track record, along with it not being classified as an antibiotic, it could be the favoured intra-canal medicament. However, most published studies utilise triple antibiotic or double antibiotic paste, thus, it’s difficult to make a direct comparison with regards to each of their clinical successes. - ANTIBIOTIC PASTES AS AN INTRACANAL MEDICAMENT

It has been seen that the microbial ecology in the canals of traumatized immature permanent teeth with infected necrotic pulp is similar to that of mature permanent teeth. Due to the pre-existing thin walls in immature permanent teeth, regular methods of biomechanical preparation is contraindicated as it could further weaken the already compromised dentinal walls. Thus, a medicated disinfection is a priority in REPs. The use of topical antimicrobial agents to sterilize or disinfect root canals has been well known and established since the early 1990s. Later, a dedicated antimicrobial paste, incorporating 3 different antibiotics (Triple Antibiotic Paste/TAP) was introduced as a method to sterilize infected root canals in vitro. The triple antibiotic paste (comprising of minocycline, ciprofloxacin, metronidazole) has been recommended as an intracanal medication in RETs, due to its excellent antimicrobial activity. However, there has been a suggestion to use another sole antibiotic in the form of Augmentin in RET, showing similar results as that of TAP. It has been shown to kill 100% of microorganisms isolated from an infected root canal that is associated with an apical abscess. However, these were in vitro antibiotic sensitivity testing and did not show its action in clinical applications. The AAE recommends the usage of TAP at a concentration no greater than 1 mg/mL (0.1-1 mg/mL) in RET in order to avoid damage of the apical papilla stem cells. However, it is important to note that as per the ESE, antibiotics should be avoided in RETs due to the absence of strong evidence to support their use. This would advocate for the use of calcium hydroxide instead of antibiotic pastes, but requires further investigation. Many studies have shown that discoloration is a significant aesthetic problem following regenerative endodontic treatment. Discoloration is more often associated with TAP that includes the antibiotic minocycline. A double antibiotic paste, excluding minocycline, could be used as an alternative to the conventional Triple antibiotic paste, where studies have shown no change in its antimicrobial efficacy when compared to TAP. - ETHYLENEDIAMINETETRAACETIC ACID

The use of Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) as a chelating agent helps to remove smear layer in conventional non-surgical root canal therapy and to cause release of growth factors from dentine matrix in RETs. This chelating agent has also been shown to have some weak antimicrobial activity. The use of 17% EDTA has been shown to result in increased SCAP survival expression as well as partially reversing the deleterious effects of NaOCl. This deleterious effect of sodium hypochlorite is that it causes damage to stem cells, leading to reduced beneficial effects from these surviving progenitor cells. Also, in cases where minimal filing has been undertaken in order to preserve existing dentinal walls, the use of EDTA and removal of the smear layer may expose binding sites for attachment of newly formed tissue to the canal walls. Thus, a final rinse using EDTA solution is advised prior to induction of a blood clot. - SCAFFOLDS/ BLOOD CLOT

The induction of an intra-canal blood clot in RET is done via intentionally provoking periapical tissue bleeding into the canal space. This is done so as to provide a blood clot, which is used as a scaffold. This introduces platelet-derived growth factors and mesenchymal stem cells into the canal space for possible pulp tissue regeneration. In cases of excessive destruction of tissues in the periapical region, induction of bleeding into the canal space may not be possible. In such cases, the procedure can be postponed, until the periapical tissues are able to recover from the injury. Alternatives, such as Platelet rich plasma (PRP) and platelet rich fibrin (PRF) have been used successfully as a scaffold instead of a blood clot in RETs. However, PRP or PRF does not provide significantly superior results than a blood clot in terms of promoting the thickening of the canal walls/continued root development in RET. Thus, taking into consideration the higher complexity in the preparation of PRP and PRF, the clinician can opt for utilising the blood clot alone, as a scaffold. Hydrogels have recently gained popularity in regenerative endodontics. Their high-water content has been shown to support diffusion of nutrients into the matrix, creating an optimal environment for cellular activity. These hydrogels can also be bioengineered to encapsulate growth factors, enabling controlled release to guide cell differentiation and tissue development. However, as these synthetic hydrogels are costly, and do not exhibit superior characteristics in comparison to a blood clot, careful planning needs to be undertaken by the clinician prior to finalizing their choice of scaffold for the REP. - AGE

It has been demonstrated that REPs can be successfully performed in patients ranging from 9-18 years of age. However, it is important to note that the main indication for REPs are for immature permanent teeth. Thus, it is seen that younger patients provide more chances of success.

Outcomes

Due to the unpredictable nature of the various outcomes seen during REPs, along with their different modes of assessment, the outcomes of REPs can be broadly classified into 2 groups as:

-

- CLINICAL OUTCOMES

Since 2001, many clinical studies of RET on human immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulp have been published. The American Association of Endodontists clinical considerations for regenerative endodontic procedures define success by three measures:- Primary goal (essential): The elimination of symptoms and the evidence of bony healing

- Secondary goal (desirable): Increased root wall thickness and/or increased root length

- Tertiary goal: positive response to vitality testing

- CLINICAL OUTCOMES

The primary goal of resolution of the signs/symptoms of infection and bone healing are generally achievable. Three systematic reviews demonstrated that this primary goal could be reliably achieved with around 91%-96% of cases resulted with periapical healing. With regards to the secondary outcome, although it has been shown that an increase in root length along with an increase in root width is possible, it is not always predictable. The success for these outcomes vary drastically from 2-70%. This unpredictability of root maturation could be attributed to the disturbance in interaction between Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath and mesenchymal stem cells in the dental follicle, caused by damage to these tissues via the periapical infection. Diogenes et al. has reported that the return of a positive response to pulp sensibility testing after RET of immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulp was seen in around 50%-60% of published cases. There is a gradual increase in response, from the period treatment has concluded up to 12 months follow up. Although, these findings vary significantly amongst studies. A positive response to pulp sensibility testing of immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulp after RET does not necessarily indicate regeneration of the pulp tissue.

It is important to also consider an undesirable outcome of RETs. MTA, used during RET as a coronal plug over the blood clot/scaffold, can also cause tooth discoloration. It has been reported that discoloration of coronal tooth structure after RET has an incidence of around 40% of cases. To minimize the risk of discoloration, Biodentine instead of MTA can be used as a coronal plug, along with usage of double antibiotic paste instead of TAP. Bleaching of discoloured teeth can be used as an effective method to improve the aesthetic outcome.

- HISTOLOGICAL OUTCOMES

The tissue formed in disinfected root canal spaces, in animal studies, was found to be hard and soft connective tissue. The tissues formed were characterised to be as bone-like, cementum-like, and periodontal ligament-like tissue. Histologic and immunohistochemical findings of a human immature permanent tooth with apical periodontitis, after regenerative endodontic therapy, revealed cementum-like, bone-like and nerve fibres in the canal, with the vital tissue not being pulp tissue.

Single-visit RET

According to the American Association of Endodontists as well as the European Society of Endodontology, the protocol for RET usually requires at least two treatment visits. This is also supported by the fact that the majority of published case reports and case series in RET used multiple visits with an intracanal medicament, such as calcium hydroxide or triple antibiotic paste. However, there have been case reports of RETs with successful treatment in a single sitting, without the use of any intracanal medicament.

Prognosis

As stated in the outcomes section, REPs have a significantly high rate of success in terms of resolving infection and periapical pathosis. They have also been demonstrated to produce continued development of the root in terms of both thickness and length. However, there is a strong risk for publication bias, as it is likely that only successful cases are being reported, as reported by Kim et.al, resulting in an over-estimation of the success of teeth treated with regenerative procedures. Also, very few of the published studies have a long term follow up, thus, inhibiting the estimation of success for RETs. Most studies provide only a 12 month follow up.

Failures in RET

As reported previously, success rates are not 100%, although being high. A recent study reported that the prevalence of revascularization-associated intracanal calcification was about 62.1%. In other words, there is increased chances of pulp canal obliteration post RET. This could raise issues with respect to retreatment of cases with failed RETs, as these calcifications would pose as a significant hurdle. The use of surgical operating microscope, ultrasonic tips and CBCT could help manage the immature permanent teeth with failed RCT. The treatment of an immature permanent tooth after failed RET includes non-surgical root canal therapy and repeating the regenerative endodontic procedure or apexification.

Comparison with Apexification

A number of systematic reviews and studies have reported that treatment of immature teeth with pulp necrosis by either RET or apexification, are comparably effective in achieving successful outcome. This is especially true in apexification cases treated with MTA. One study, however, reported greater instances of adverse effects post REPs as compared to apexification. An important consideration during treatment planning is that further root maturation can only be achieved in teeth treated with RET. Therefore, in teeth with a compromised radicular apparatus and a necrotic pulp, RETs should be the treatment of choice.

Protocol for Follow-Ups

Most available studies in the literature have short-term follow-ups because RET is still a relatively new treatment option in endodontics. Similar to nonsurgical root canal therapy, a long-term follow-up is necessary in order to assure the long-term treatment outcome. The ESE advised follow ups at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and yearly for 5 years to ensure elimination of symptoms and monitoring of any new developments.

Conclusion

Regenerative endodontic procedures are not only effective in elimination of patients’ clinical symptom/signs and resolve apical periodontitis, which is the primary goal of endodontic therapy, but also continue root development (thickening of the canal walls and/or apical closure). With the current limitations of technology and literature, REPs serve as the only clinical protocol that can achieve these goals. Although the tissue formed post regenerative procedures have been found not to be similar to that of the pulp, the tissues formed are effective in achieving the goals of REPs, mainly resolution of symptoms and continued development of the compromised root system in immature permanent teeth. Traditional treatment modalities such as apexification offer the clinician similar success rates, if not higher. However, in contrast to apexification, RET has the potential to encourage continued root maturation of immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulp/apical periodontitis. In cases of failure, the case could be retreated again with RET or with a more traditional method of apexification or conventional non-surgical root canal treatment, without causing any harm to the patient. Thus, based on a patient centric approach, along with considerations of failures and success, RETs should be used whenever possible in cases of immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulps.

Conflict Of Interest

Nil

References

- Nygaard‐östby B, Hjortdal O. Tissue formation in the root canal following pulp removal. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 1971;79(3):333-349. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0722.1971.tb02019.x

- Iwaya S, Ikawa M, Kubota M. Revascularization of an immature permanent tooth with apical periodontitis and sinus tract. Dental Traumatology. 2001;17(4):185-187. doi:10.1034/j.1600-9657.2001.017004185.x

- Trope M. Reply. Journal of Endodontics. 2008;34(5):511-512. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.010

- Murray PE, Garcia-Godoy F, Hargreaves KM. Regenerative Endodontics: a review of current status and a call for action. Journal of Endodontics. 2007;33(4):377-390. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2006.09.013

- Rafter M. Apexification: a review. Dental Traumatology. 2005;21(1):1-8. doi:10.1111/j.1600-9657.2004.00284.x

- Kim SG, Malek M, Sigurdsson A, Lin LM, Kahler B. Regenerative endodontics: a comprehensive review. International Endodontic Journal. 2018;51(12):1367-1388. doi:10.1111/iej.12954

- Almutairi W, Yassen GH, Aminoshariae A, Williams KA, Mickel A. Regenerative Endodontics: A systematic analysis of the failed cases. Journal of Endodontics. 2019;45(5):567-577. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2019.02.004

- Valsan D, Pulyodan M, Mohan S, Divakar N, Moyin S, Thayyil S. Regenerative endodontics: A paradigm shift in clinical endodontics. Journal of Pharmacy and Bioallied Sciences. 2020;12(5):20. doi:10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_112_20

- Galler KM, Krastl G, Simon S, et al. European Society of Endodontology position statement: Revitalization procedures. International Endodontic Journal. 2016;49(8):717-723. doi:10.1111/iej.12629

- Ricucci D, Siqueira JF, Loghin S, Lin LM. Pulp and apical tissue response to deep caries in immature teeth: A histologic and histobacteriologic study. Journal of Dentistry. 2016;56:19-32. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2016.10.005

- Horan MA, Ashcroft GS. Ageing, defence mechanisms and the immune system. Age And Ageing. 1997;26(suppl 4):15-19. doi:10.1093/ageing/26.suppl_4.15

- Chen MY ‐h., Chen K ‐l., Chen C ‐a., Tayebaty F, Rosenberg PA, Lin LM. Responses of immature permanent teeth with infected necrotic pulp tissue and apical periodontitis/abscess to revascularization procedures. International Endodontic Journal. 2011;45(3):294-305. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01978.x

- Kontakiotis EG, Filippatos CG, Tzanetakis GN, Agrafioti A. Regenerative Endodontic therapy: A data analysis of clinical protocols. Journal of Endodontics. 2014;41(2):146-154. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2014.08.003

- Diogenes A, Henry MA, Teixeira FB, Hargreaves KM. An update on clinical regenerative endodontics. Endodontic Topics. 2013;28(1):2-23. doi:10.1111/etp.12040

- AAE Clinical Considerations for a Regenerative Procedure Revised 2021. aae.org. https://www.aae.org/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/08/ClinicalConsiderationsApprovedByREC062921.pdf. Published 2021. Accessed August 10, 2025.

- Siqueira JF. Reaction of periradicular tissues to root canal treatment: benefits and drawbacks. Endodontic Topics. 2005;10(1):123-147. doi:10.1111/j.1601-1546.2005.00134.x

- Fang Y, Wang X, Zhu J, Su C, Yang Y, Meng L. Influence of Apical Diameter on the Outcome of Regenerative Endodontic Treatment in Teeth with Pulp Necrosis: A Review. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;44(3):414-431. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2017.10.007

- Estefan BS, Batouty KME, Nagy MM, Diogenes A. Influence of age and apical diameter on the success of endodontic regeneration procedures. Journal of Endodontics. 2016;42(11):1620-1625. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2016.06.020

- Alothman FA, Hakami LS, Alnasser A, AlGhamdi FM, Alamri AA, Almutairii BM. Recent Advances in Regenerative Endodontics: A review of current techniques and future directions. Cureus. November 2024. doi:10.7759/cureus.74121

- Kim S. Infection and pulp regeneration. Dentistry Journal. 2016;4(1):4. doi:10.3390/dj4010004

- Wang X, Thibodeau B, Trope M, Lin LM, Huang GT j. Histologic Characterization of Regenerated Tissues in Canal Space after the Revitalization/Revascularization Procedure of Immature Dog Teeth with Apical Periodontitis. Journal of Endodontics. 2009;36(1):56-63. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2009.09.039

- Becerra P, Ricucci D, Loghin S, Gibbs JL, Lin LM. Histologic Study of a Human Immature Permanent Premolar with Chronic Apical Abscess after Revascularization/Revitalization. Journal of Endodontics. 2013;40(1):133-139. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2013.07.017

- Lei L, Chen Y, Zhou R, Huang X, Cai Z. Histologic and Immunohistochemical Findings of a Human Immature Permanent Tooth with Apical Periodontitis after Regenerative Endodontic Treatment. Journal of Endodontics. 2015;41(7):1172-1179. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2015.03.012

- Fouad AF. Microbial factors and antimicrobial strategies in dental pulp regeneration. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;43(9):S46-S50. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2017.06.010

- Huang GT, Gronthos S, Shi S: Mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental tissues vs. those from other sources: their biology and role in regenerative medicine. J Dent Res. 2009, 88:792-806. doi:10.1177/0022034509340867

- Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, Brem H, Tomic‐Canic M. PERSPECTIVE ARTICLE: Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2008;16(5):585-601. doi:10.1111/j.1524-475x.2008.00410.x

- Galler KM, Buchalla W, Hiller KA, et al. Influence of Root Canal Disinfectants on Growth Factor Release from Dentin. Journal of Endodontics. 2015;41(3):363-368. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2014.11.021

- Sadaghiani L, Alshumrani AM, Gleeson HB, Ayre WN, Sloan AJ. Growth factor release and dental pulp stem cell attachment following dentine conditioning: An in vitro study. International Endodontic Journal. 2022;55(8):858-869. doi:10.1111/iej.13781

- Vo TN, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Strategies for controlled delivery of growth factors and cells for bone regeneration. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2012;64(12):1292-1309. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.01.016

- Kim SG. Biological molecules for the regeneration of the Pulp-Dentin complex. Dental Clinics of North America. 2016;61(1):127-141. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2016.08.005

- Alamoudi R. The smear layer in endodontic: To keep or remove – an updated overview. Deleted Journal. 2019;9(2):71. doi:10.4103/sej.sej_95_18

- Sena NT, Gomes BPFA, Vianna ME, et al. In vitro antimicrobial activity of sodium hypochlorite and chlorhexidine against selected single‐species biofilms. International Endodontic Journal. 2006;39(11):878-885. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01161.x

- Martin DE, De Almeida JFA, Henry MA, et al. Concentration-dependent effect of sodium hypochlorite on stem cells of apical papilla survival and differentiation. Journal of Endodontics. 2013;40(1):51-55. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2013.07.026

- Trevino EG, Patwardhan AN, Henry MA, et al. Effect of irrigants on the survival of human stem cells of the apical papilla in a platelet-rich plasma scaffold in human root tips. Journal of Endodontics. 2011;37(8):1109-1115. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2011.05.013

- C E, Gb S, Ll B, O FJ. Mechanism of action of calcium and hydroxyl ions of calcium hydroxide on tissue and bacteria. PubMed. 1995;6(2):85-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8688662.

- Kitikuson P, Srisuwan T. Attachment Ability of Human Apical Papilla Cells to Root Dentin Surfaces Treated with Either 3Mix or Calcium Hydroxide. Journal of Endodontics. 2015;42(1):89-94. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2015.08.021

- Nagata JY, Soares AJ, Souza-Filho FJ, et al. Microbial Evaluation of Traumatized Teeth Treated with Triple Antibiotic Paste or Calcium Hydroxide with 2% Chlorhexidine Gel in Pulp Revascularization. Journal of Endodontics. 2014;40(6):778-783. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2014.01.038

- Grossman L. Antimicrobial effect of root canal cements. Journal of Endodontics. 1980;6(6):594-597. doi:10.1016/s0099-2399(80)80019-7

- Hoshino E, Kurihara‐ando N, Sato I, et al. In‐vitro antibacterial susceptibility of bacteria taken from infected root dentine to a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and minocycline. International Endodontic Journal. 1996;29(2):125-130. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2591.1996.tb01173.x

- Sato I, Ando‐kurihara N, Kota K, Iwaku M, Hoshino E. Sterilization of infected root‐canal dentine by topical application of a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and minocycline in situ. International Endodontic Journal. 1996;29(2):118-124. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2591.1996.tb01172.x

- Nosrat A, Li KL, Vir K, Hicks ML, Fouad AF. Is pulp regeneration necessary for root maturation? Journal of Endodontics. 2013;39(10):1291-1295. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2013.06.019

- Baumgartner J, Xia T. Antibiotic Susceptibility of Bacteria Associated with Endodontic Abscesses. Journal of Endodontics. 2003;29(1):44-47. doi:10.1097/00004770-200301000-00012

- Sharma S, Bhushan U, Goswami M, Baveja C. Comparative evaluation of two antibiotic pastes for root canal disinfection. International Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 2022;15(S1):S12-S17. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1898

- Baziar M, Mehrasebi MR, Assadi A, Fazli MM, Maroosi M, Rahimi F. Erratum to: Efficiency of non-ionic surfactants – EDTA for treating TPH and heavy metals from contaminated soil. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering. 2014;12(1). doi:10.1186/2052-336x-12-47

- Galler KM, D’Souza RN, Federlin M, et al. Dentin Conditioning codetermines cell fate in regenerative endodontics. Journal of Endodontics. 2011;37(11):1536-1541. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2011.08.027

- Petrino JA, Boda KK, Shambarger S, Bowles WR, McClanahan SB. Challenges in Regenerative Endodontics: a case series. Journal of Endodontics. 2009;36(3):536-541. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2009.10.006

- Nosrat A, Homayounfar N, Oloomi K. Drawbacks and unfavorable outcomes of regenerative endodontic treatments of necrotic immature teeth: a literature review and report of a case. Journal of Endodontics. 2012;38(10):1428-1434. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2012.06.025

- Caviedes‐Bucheli J, Muñoz‐Alvear HD, Lopez‐Moncayo LF, et al. Use of scaffolds and regenerative materials for the treatment of immature necrotic permanent teeth with periapical lesion: Umbrella review. International Endodontic Journal. 2022;55(10):967-988. doi:10.1111/iej.13799

- Torabinejad M, Turman M. Revitalization of Tooth with Necrotic Pulp and Open Apex by Using Platelet-rich Plasma: A Case Report. Journal of Endodontics. 2011;37(2):265-268. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2010.11.004

- Jadhav G, Shah N, Logani A. Revascularization with and without Platelet-rich Plasma in Nonvital, Immature, Anterior Teeth: A Pilot Clinical Study. Journal of Endodontics. 2012;38(12):1581-1587. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2012.09.010

- Bezgin T, Yilmaz AD, Celik BN, Kolsuz ME, Sonmez H. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma as a scaffold in regenerative endodontic treatment. Journal of Endodontics. 2014;41(1):36-44. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2014.10.004

- Bakhtiar H, Esmaeili S, Tabatabayi SF, Ellini MR, Nekoofar MH, Dummer PMH. Second-generation platelet concentrate (Platelet-rich fibrin) as a scaffold in regenerative endodontics: a case series. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;43(3):401-408. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2016.10.016

- Narang I, Mittal N, Mishra N. A comparative evaluation of the blood clot, platelet-rich plasma, and platelet-rich fibrin in regeneration of necrotic immature permanent teeth: A clinical study. Contemporary Clinical Dentistry. 2015;6(1):63. doi:10.4103/0976-237x.149294

- Lolato A, Bucchi C, Taschieri S, Kabbaney AE, Del Fabbro M. Platelet concentrates for revitalization of immature necrotic teeth: a systematic review of the clinical studies. Platelets. 2016;27(5):383-392. doi:10.3109/09537104.2015.1131255

- Zhou R, Wang Y, Chen Y, et al. Radiographic, Histologic, and Biomechanical Evaluation of Combined Application of Platelet-rich Fibrin with Blood Clot in Regenerative Endodontics. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;43(12):2034-2040. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2017.07.021

- Aksel H, Serper A: Recent considerations in regenerative endodontic treatment approaches. J Dent. 2014, 9:1-7. doi:10.1016/j.jds.2013.12.007

- Antunes LS, Salles AG, Gomes CC, Andrade TB, Delmindo MP, Antunes LA. The effectiveness of pulp revascularization in root formation of necrotic immature permanent teeth: A systematic review. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 2015;74(3):161-169. doi:10.3109/00016357.2015.1069394

- Tong HJ, Rajan S, Bhujel N, Kang J, Duggal M, Nazzal H. Regenerative Endodontic Therapy in the Management of Nonvital Immature Permanent Teeth: A Systematic Review—Outcome Evaluation and Meta-analysis. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;43(9):1453-1464. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2017.04.018

- Torabinejad M, Nosrat A, Verma P, Udochukwu O. Regenerative Endodontic Treatment or Mineral Trioxide Aggregate Apical Plug in Teeth with Necrotic Pulps and Open Apices: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;43(11):1806-1820. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2017.06.029

- Alghamdi F, Alsulaimani M. Regenerative endodontic treatment: A systematic review of successful clinical cases. Dental and Medical Problems. 2021;58(4):555-567. doi:10.17219/dmp/132181

- Kahler B, Mistry S, Moule A, et al. Revascularization outcomes: A prospective analysis of 16 consecutive cases. Journal of Endodontics. 2013;40(3):333-338. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2013.10.032

- Alobaid AS, Cortes LM, Lo J, et al. Radiographic and clinical outcomes of the treatment of immature permanent teeth by revascularization or apexification: a pilot retrospective cohort study. Journal of Endodontics. 2014;40(8):1063-1070. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2014.02.016

- Saoud TMA, Zaazou A, Nabil A, Moussa S, Lin LM, Gibbs JL. Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes of Traumatized Immature Permanent Necrotic Teeth after Revascularization/Revitalization Therapy. Journal of Endodontics. 2014;40(12):1946-1952. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2014.08.023

- Li L, Pan Y, Mei L, Li J. Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes in Immature Permanent Necrotic Evaginated Teeth Treated with Regenerative Endodontic Procedures. Journal of Endodontics. 2016;43(2):246-251. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2016.10.015

- Nageh M, Ahmed GM, El-Baz AA. Assessment of Regaining Pulp Sensibility in Mature Necrotic Teeth Using a Modified Revascularization Technique with Platelet-rich Fibrin: A Clinical Study. Journal of Endodontics. 2018;44(10):1526-1533. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2018.06.014

- Parirokh M, Torabinejad M. Mineral Trioxide Aggregate: A Comprehensive Literature Review—Part III: Clinical Applications, Drawbacks, and Mechanism of Action. Journal of Endodontics. 2010;36(3):400-413. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2009.09.009

- Marconyak LJ, Kirkpatrick TC, Roberts HW, et al. A comparison of coronal tooth discoloration elicited by various endodontic reparative materials. Journal of Endodontics. 2015;42(3):470-473. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2015.10.013

- Shokouhinejad N, Nekoofar MH, Pirmoazen S, Shamshiri AR, Dummer PMH. Evaluation and Comparison of Occurrence of Tooth Discoloration after the Application of Various Calcium Silicate–based Cements: An Ex Vivo Study. Journal of Endodontics. 2015;42(1):140-144. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2015.08.034

- Kirchhoff AL, Raldi DP, Salles AC, Cunha RS, Mello I. Tooth discolouration and internal bleaching after the use of triple antibiotic paste. International Endodontic Journal. 2014;48(12):1181-1187. doi:10.1111/iej.12423

- Thibodeau B, Teixeira F, Yamauchi M, Caplan DJ, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. Journal of Endodontics. 2007;33(6):680-689. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2007.03.001

- Yamauchi N, Yamauchi S, Nagaoka H, et al. Tissue Engineering Strategies for Immature Teeth with Apical Periodontitis. Journal of Endodontics. 2011;37(3):390-397. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2010.11.010

- Arslan H, Şahin Y, Topçuoğlu HS, Gündoğdu B. Histologic Evaluation of Regenerated Tissues in the Pulp Spaces of Teeth with Mature Roots at the Time of the Regenerative Endodontic Procedures. Journal of Endodontics. 2019;45(11):1384-1389. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2019.07.016

- Topçuoğlu G, Topçuoğlu HS. Regenerative endodontic therapy in a single visit using platelet-rich plasma and biodentine in necrotic and asymptomatic immature molar teeth: a report of 3 cases. Journal of Endodontics. 2016;42(9):1344-1346. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2016.06.005

- Chaniotis A. The use of a single‐step regenerative approach for the treatment of a replanted mandibular central incisor with severe resorption. International Endodontic Journal. 2015;49(8):802-812. doi:10.1111/iej.12515

- Nassar MA, Roshdy NN, Kataia M, Mousa H, Sabet N. Assessment of the Clinical Outcomes of Single Visit Regenerative Endodontic Procedure In Treating Necrotic Mature Teeth with Apical Periodontitis Using Biological Irrigating Solution. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2023;11(D):61-64. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2023.11314

- McCabe P. Revascularization of an immature tooth with apical periodontitis using a single visit protocol: a case report. International Endodontic Journal. 2014;48(5):484-497. doi:10.1111/iej.12344

- Conde MCM, Chisini LA, Sarkis‐Onofre R, Schuch HS, Nör JE, Demarco FF. A scoping review of root canal revascularization: relevant aspects for clinical success and tissue formation. International Endodontic Journal. 2016;50(9):860-874. doi:10.1111/iej.12711

- Song M, Cao Y, Shin SJ, et al. Revascularization-associated intracanal calcification: Assessment of prevalence and contributing factors. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;43(12):2025-2033. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2017.06.018

- Silujjai J, Linsuwanont P. Treatment Outcomes of apexification or revascularization in nonvital immature permanent teeth: a retrospective study. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;43(2):238-245. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2016.10.030

- Lin J, Zeng Q, Wei X, et al. Regenerative Endodontics Versus Apexification in Immature Permanent Teeth with Apical Periodontitis: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;43(11):1821-1827. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2017.06.023

- Bose R, Nummikoski P, Hargreaves K. A retrospective evaluation of radiographic outcomes in immature teeth with necrotic root canal systems treated with regenerative endodontic procedures. Journal of Endodontics. 2009;35(10):1343-1349. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2009.06.021

- De Toubes KMS, De Oliveira PAD, Machado SN, Pelosi V, Nunes E, Silveira FF. Clinical Approach to Pulp Canal Obliteration: A case series. PubMed. 2017;12(4):527-533. doi:10.22037/iej.v12i4.18006

- Žižka R, Buchta T, Voborná I, Harvan L, Šedý J. Root maturation in teeth treated by unsuccessful revitalization: 2 case reports. Journal of Endodontics. 2016;42(5):724-729. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2016.02.004

- Chaniotis A. Treatment options for failing regenerative endodontic procedures: Report of 3 cases. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;43(9):1472-1478. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2017.04.015

- Keinan D, Nuni E, Rainus MB, Simhon TB, Dakar A, Slutzky-Goldberg I. Retreatment of failed regenerative Endodontic therapy: outcome and treatment considerations. Cureus. December 2024. doi:10.7759/cureus.75147