Resilience in Mozambique: Addressing Climate-Health Disasters

Recovery and Resilience from Climate-Related Health Disasters in Mozambique

Patrick T. Panos1, Angelea Panos2,

- College of Social Work, University of Utah

- Social & Behavioral Sciences, Utah Valley University

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 June 2025

CITATION: Panos, TP., and Panos, A., 2025. Recovery and Resilience from Climate-Related Health Disasters in Mozambique. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(6). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6633

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6633

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Objectives of Study: This study examines how Mozambique is building resilience and strengthening recovery efforts in response to climate-related health disasters. It assesses how local partnerships foster inclusive, community-based disaster health risk reduction strategies, particularly for vulnerable populations, using Non-Governmental Organizations, Community Councils, and Civil Society Organizations.

Introduction: Mozambique is one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries, facing frequent and increasingly intense disasters such as cyclones, floods, and cholera outbreaks. The compounded effects of health disparities, poverty, and fragile infrastructure create high susceptibility to cascading crises. In response, Mozambique has begun shifting toward a decentralized, participatory model that utilizes Non-Governmental Organizations and community structures to scale public health preparedness, resilience, and climate adaptation.

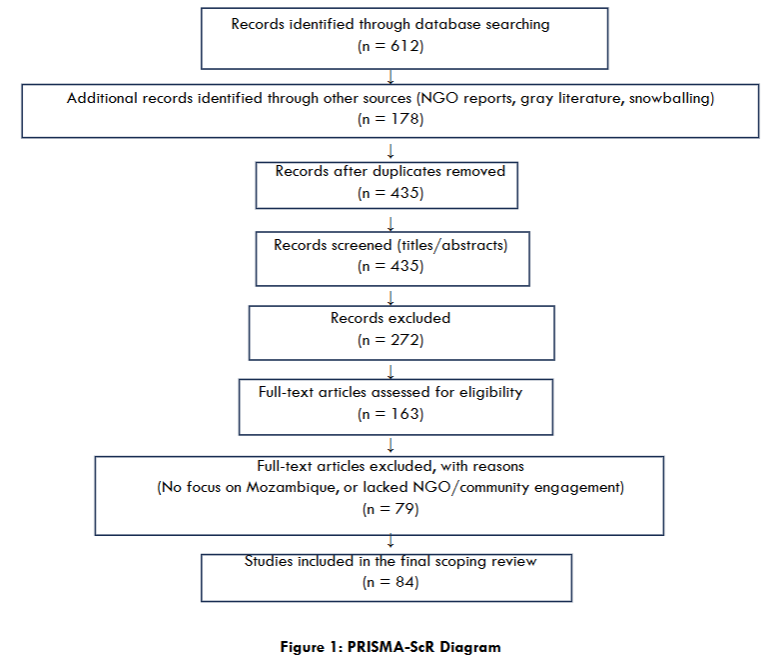

Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted across academic databases and gray literature (2010–2025) to identify relevant publications discussing Non-Governmental Organization/community-based disaster management in Mozambique. Studies were included if they examined public health, resilience strategies, or climate adaptation involving Non-Governmental Organizations or community councils, especially those addressing marginalized populations. A total of 84 studies were selected after applying inclusion/exclusion criteria. Data were thematically analyzed to synthesize common strategies, implementation models, and outcomes.

Conclusions: Findings reveal that a factor of Mozambique’s resilience is due to integrating local leadership with international support. Non-Governmental Organizations and community council partnerships have been instrumental in promoting public health by strengthening early warning systems, investing in climate-resilient infrastructure, and reducing social inequalities. Inclusive planning involving women, the elderly, and people with disabilities has enhanced recovery outcomes. Sustained resilience will require institutional reforms, localized funding models, and long-term investment in community empowerment. Mozambique offers a valuable case study for how locally led, globally supported resilience frameworks can address the intersection of climate, health, and equity in disaster-prone regions.

Keywords

- Public Health

- Mozambique

- Resiliency

- Community Resilience

- Disaster Risk Reduction

- Civil Society Organizations (CSOs)

- Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO)

- Community Councils

- Inclusive Disaster Management

Introduction

Africa, as a continent, is experiencing rising temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, and an increase in more frequent and intense extreme weather events, including droughts, floods, and cyclones. Furthermore, the catastrophic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside the escalating climate emergencies, starkly revealed how disasters trigger widespread systemic risks and unleash cascading effects that devastate communities, economies, and health systems, especially in vulnerable regions. Many African countries have limited resources and infrastructure, making them more vulnerable to both climate and health disasters. There are profound health implications due to loss and damage associated with disasters, including disease, destruction of healthcare infrastructure, and mental health impacts affecting the most vulnerable people in these communities. Additionally, many African countries rely on agriculture for their livelihoods and nutrition, which is heavily impacted by climate change. Consequently, the continent reported an estimated 1,700 natural disasters with economic losses totaling US$38.5 billion from 1970 to 2019. In response to this vulnerability, the United Nations (UN) Office for Disaster Risk Reduction has sought to develop and strengthen health and disaster risk reduction strategies by bolstering the use of local volunteer agencies and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs). Similarly, the World Health Organization has sought to use the “untapped resources” of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) working within various developing and underserved countries. This scoping review article examines how Mozambique is using local NGOs, along with the existing community and civil society organizations, to enhance their preparedness and resiliency to address future climate-related health disaster recovery efforts.

Being the fifth poorest country in the world, Mozambique faces unique challenges to being resilient in the face of disasters. Located in southeast Africa, and with a long coastline (2,700 km) along the Indian Ocean, it is highly prone to climate disasters due to tropical storms and cyclones. This vulnerability is exacerbated by rising sea levels, warming ocean temperatures, and unpredictable rainfall patterns that increase storm intensity and flooding. Major rivers like the Zambezi, Limpopo, and Save frequently overflow, causing floods—especially during heavy rains upstream. Additionally, the majority of Mozambique’s 33 million (2025 estimate) live along the low-lying coastal plains that are vulnerable to storm surges and flooding. Poor agricultural practices, loss of forest cover, and inept land management increase landslide and flood risks. Many people live in poorly built mud housing in the flood-prone areas and lack access to clean water, proper sanitation, early warning systems, and resilient infrastructure. With widespread chronic poverty, inadequate health services, and heavy reliance on subsistence agriculture (80%), any changes to the nation’s ecosystems have an immediate impact on its population.

Over the last decade, Mozambique has experienced an increasing number of cyclones. For instance, in 2019, Cyclones Idai and Kenneth marked the first time in recorded history that two strong tropical cyclones struck Mozambique in the same season. According to UNICEF, Cyclone Idai resulted in 603 deaths, 1,641 injuries, and the destruction of 223,947 houses, displacing 160,927 people. Cyclone Kenneth, hitting six weeks later, destroyed over 30,000 homes and displaced approximately 20,000 individuals. Since that time, the Mozambican Meteorological Institute (INAM) reports that between 2021 and 2025 alone, the country was struck by ten tropical cyclones, surpassing the totals of previous decades. More recently, in 2023, Cyclone Freddy lasted over five weeks, making it the longest-lasting tropical cyclone on record. It also generated the highest accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) ever recorded for a single storm. As a result of this storm, more than 132,000 houses were destroyed, 123 health facilities were destroyed, and more than 1 million people were affected by cholera. As a result of this increasing series of disasters, Mozambique began a transformation to both focus on disaster risk reduction strategies and climate resilience. In part, Mozambique is using a model developed during the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time, the World Health Organization (WHO) realized that many communities in developing countries could not fully respond to the health disaster as a result of shortages in medical supplies and healthcare services. Consequently, the WHO began an initiative to engage the “untapped resources” of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) working within various developing and underserved countries. A CSO is a non-profit, voluntary group of citizens that works to improve society on a local, national, or international level. Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) can be Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), civil organizations, cooperatives, social movements, professional groups, or business groups. Consequently, there was a clear improvement in a community’s ability to respond to a public health crisis or climate disaster when CSO/NGO/community partnerships are leveraged. This is particularly true in communities where CSOs/NGOs have developed relationships and have developed community leadership structures. Within medical research, it is imperative to recognize that climate-related disasters, particularly in regions like Mozambique, have profound and measurable consequences on public health. These include outbreaks of infectious diseases such as cholera, disruptions to maternal and child health services, and long-term psychosocial trauma, particularly for vulnerable populations. As the World Health Organization emphasizes, resilience strategies that integrate community-based partnerships are foundational to building climate-resilient health systems and ensuring continuity of care during crises. In this sense, disaster recovery and resilience must be considered within the broader domain of medical and health research, especially when health equity, healthcare infrastructure, and health system preparedness are core outcomes of resilience efforts.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted to map the existing literature on the role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and community councils in enhancing disaster resilience in Mozambique, with particular attention to inclusive approaches that address the needs of vulnerable populations. This review followed the methodological framework established by Arksey and O’Malley, refined by Levac et al., and aligned with the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines for scoping reviews.

STEP 1: IDENTIFYING THE RESEARCH QUESTION

The guiding question for this review was: What strategies and roles have NGOs and community-based councils played in improving health and disaster resilience in Mozambique, particularly with respect to inclusivity for vulnerable groups such as women, children, the elderly, and people with disabilities?

STAGE 2: IDENTIFYING RELEVANT STUDIES

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across multiple databases, including Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and institutional repositories (e.g., International Federation of Red Cross (IFRC), United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), World Bank, African Risk Capacity). Gray literature from government agencies and NGOs operating in Mozambique was also included. Search terms included combinations of: “Mozambique,” “disaster risk reduction,” “resilience,” “NGO,” “community council,” “inclusive disaster management,” “climate adaptation,” and “vulnerable populations.” Searches covered publications from January 2010 to April 2025, in English and Portuguese. Review articles were searched for additional relevant citations. No authors were contacted. Subsequently, research librarians provided additional recommendations in February 2025, incorporating grey literature.

STAGE 3: STUDY SELECTION

Inclusion criteria were: (1) empirical studies, program reports, or policy analyses focused on Mozambique; (2) relevance to disaster risk management, climate adaptation, or post-disaster recovery; (3) discussion of NGO or community council involvement; and (4) explicit or implicit focus on improving health for vulnerable groups. Studies were excluded if they did not focus on Mozambique or if they lacked discussion of community-level interventions or institutional engagement. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers, followed by full-text screening. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. (see Figure 1).

STAGE 4: DATA CHARTING

A standardized data extraction form was developed to chart key information, including publication type, year, geographical focus, intervention type, stakeholder roles, inclusion strategies for vulnerable populations, and reported outcomes. Data were entered into a shared spreadsheet and reviewed for consistency and completeness.

STAGE 5: COLLATING, SUMMARIZING, AND REPORTING RESULTS

Extracted data were analyzed thematically to identify recurring strategies, implementation models, and cross-cutting challenges. Findings were synthesized narratively, with special attention to (1) integrated approaches to resilience, (2) inclusivity in disaster governance, and (3) community empowerment through participatory structures. A PRISMA-ScR flow diagram was used to document the study selection process.

Results: Identification of Key Strategies for Recovery and Resilience

Recognizing the interconnectedness of climate adaptation and public health, this review seeks to identify the full range of roles played by local partnerships in Mozambique’s disaster resilience framework. Specifically, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), Community Councils, and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) have emerged as critical actors in designing and implementing inclusive, community-based strategies that prioritize health, safety, and recovery for vulnerable populations. These partnerships foster trust, build localized early warning systems, integrate indigenous knowledge, and enhance infrastructure that supports both climate and health resilience. As demonstrated during recent cyclones and the COVID-19 pandemic, local organizations are often first responders and long-term stewards of community recovery, making them central to any public health response to disasters. Their embedded presence within communities allows for nuanced, adaptive approaches that national systems alone cannot deliver, particularly in low-resource, high-risk settings.

The international support to institutions such as local SCOs and NGOs, along with the existing community and civil society, was key to Mozambique’s ability to respond to COVID-19. The following describes how Mozambique is using SCOs and NGOs as part of its key strategies for recovery and resilience to prepare for future climate-related health disasters.

STRENGTHENING EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS AND ANTICIPATORY ACTION

Mozambique has made significant strides in developing early warning systems to anticipate and prepare for climate-related disasters. The “Ready, Set & Go!” system, implemented through a collaboration of local non-governmental organizations at the community level, as well as the World Food Programme and the Mozambique National Meteorology Institute, uses seasonal forecasts and predefined triggers to initiate “anticipatory actions” such as food distribution and livestock relocation. This system has been shown to reduce the impact of droughts by optimizing the use of seasonal forecast information and minimizing false alarms. Early outcomes are showing the collaboration of such a system with local agencies is potentially a sustainable way to support climate-vulnerable governments with limited resources.

INTEGRATING LOCAL AND INDIGENOUS RESILIENCE STRATEGIES

In Mozambique, local advisory boards and community councils play a crucial role in enabling communities to express their public health needs and priorities directly to local governments. These councils participate in a participatory and inclusive decision-making process for local development planning, ensuring that community voices influence resource allocation and project priorities. For example, through the Local Climate Adaptive Living Facility (LoCAL), local councils have been instrumental in coordinating with government agencies to address climate adaptation and public health needs, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, local associations and community councils in the Nampula region of Mozambique have developed resilience strategies that are historically rooted and adapted to local contexts. As one farmer stated regarding the importance of such coordination, “As peasants, we can’t leave our old ways of production behind because our old ways of production are based on local seeds.” These historic strategies include water sanitation and management, and social support networks. Outcome research within small communities highlights the importance of recognizing and supporting these strategies, as they are holistic and address multiple challenges beyond climate-related health issues. However, barriers such as the limited recognition of indigenous knowledge in formal decision-making processes must be addressed.

INVESTING IN CLIMATE-RESILIENT INFRASTRUCTURE

Mozambique has prioritized the development of climate-resilient infrastructure, particularly in urban area communities. For example, in the city of Beira, which was dramatically affected by Cyclones Idai and Kenneth, local committees and subsidiary community leaders have become the backbone of resilience efforts, coordinating aid and disaster relief at the district and neighborhood levels. These committees foster strong community bonds and work closely with municipal authorities to implement recovery and resilience projects. Through collaborations with local associations, the Beira City Council has implemented nature-based solutions such as green roofs, urban farming, and rainwater collection systems. Projects in cities such as Beira, Quelimane, and Nacala have demonstrated the effectiveness of nature-based solutions in reducing flood risks while providing additional benefits such as improved biodiversity and water quality. These measures are part of a broader effort to enhance urban resilience through cooperation with local associations to address multiple climate-related health hazards. Additionally, in collaboration with international partners, the Mozambican government has launched initiatives aimed at enhancing the resilience of clean water, sanitation, and drainage infrastructure. These efforts have focused on strengthening institutional capacity, training local personnel, and incorporating climate modeling into policy and planning frameworks. Educational outreach on water purification practices delivered to families and community leaders has also contributed to a notable decline in infant and child mortality.

PROMOTING FOOD SECURITY

Agriculture is a critical sector in Mozambique, and climate change poses significant threats to food security. Supported by NGOs and community organizations working in tandem with government efforts, Mozambique has implemented its National Adaptation Plan. The strategies include improved crop varieties, soil conservation, and irrigation at the local level. Additionally, investments in agricultural infrastructure, such as roads and storage facilities, are essential for building the resilience of local communities. Furthermore, building climate resilience in Mozambique’s agricultural sector depends heavily on improving communication between local farmers and state institutions.

FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT AND PUBLIC HEALTH AWARENESS

Mozambique has implemented flood risk management strategies that combine biophysical, public health, and economic assessments. These strategies include the use of hydrological models to predict flood risks and the development of nonstructural measures such as flood preparedness and evacuation plans. Community participation in flood risk management has been particularly effective in reducing vulnerability in rural areas. These approaches include the development of educational tools, such as posters and card games, to improve flood preparedness among schoolchildren and local communities.

DEVELOPING LOCAL LEADERSHIP AND HOLISTIC COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

Holistic community development can have long-term effects that support local empowerment and resiliency during disasters. For instance, the NGO Care for Life (CFL) works in rural regions engaging in comprehensive community development covering eight areas: health, sanitation, education, food security and nutrition, income generation, housing, psycho-social well-being, and community-participation and leadership-development. By addressing all eight domains simultaneously through participatory education and local leadership development, CFL was shown to foster a self-sustaining, resilient, empowered community. This multidimensional approach enabled residents to bounce back more quickly from natural disasters (Cyclones Idai and Kenneth) and the COVID-19 pandemic, thus demonstrating tangible resiliency and improved health outcomes.

ADDRESSING COMPOUNDING HEALTH RISKS IN VULNERABLE REGIONS

The Cabo Delgado region of northern Mozambique faces overlapping public health risks stemming from climate disasters, armed conflict, and entrenched socioeconomic hardships. Addressing these challenges effectively requires an integrated resilience strategy that combines risk reduction with long-term recovery planning. Emphasizing human development and social equity within these approaches is essential for ensuring inclusive and sustainable outcomes. In response to the overlapping challenges of conflict, climate change, and poverty in Cabo Delgado, a range of integrated resilience programs have emerged, many driven by NGOs in coordination with community councils. These initiatives, which include the Mozambique Community Resilience Program (Tuko Pamoja), the Mozambique Climate Resilience Program led by IDH, and the Triple Nexus approach, share a common focus on strengthening local capacities, empowering youth and women, building healthcare infrastructure, and fostering collaboration between communities and government. Emphasis is placed on community-based participatory action planning, economic inclusion, and sustainable development, with climate adaptation, peacebuilding, and social equity treated as interdependent goals to promote public health. Across all efforts, community engagement, institutional accountability, and locally driven solutions form the backbone of long-term resilience-building in northern Mozambique.

INCLUSIVE DISASTER MANAGEMENT AND PUBLIC HEALTH RESPONSES

Inclusive disaster management and public health responses in Mozambique increasingly rely on NGOs and community councils to ensure the needs of vulnerable populations, such as children, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities, are addressed in both planning and response efforts. Community-based disaster risk management (CBDRM) initiatives have been supported by organizations like World Vision, which helped integrate disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation into district development plans. In Mozambique, over 1,400 local disaster risk reduction committees comprising nearly 20,000 volunteers have been established to support the National Institute for Disaster Management (INGD) in preparing communities and identifying local vulnerabilities. These efforts are complemented by strengthened early warning systems, including SMS alerts and community radio broadcasting, coordinated by trained local committees. Gender-inclusive strategies further ensure that women and marginalized groups are factored into all stages of disaster planning. Additionally, legal assessments by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies have recommended reforms to Mozambique’s disaster recovery policies to promote sustainable, community-centered rebuilding processes. Collectively, these efforts align with international human rights frameworks and reflect the broader shift toward inclusive, equity-based disaster resilience.

Lessons Learned and Future Directions for Public Health

IMPORTANCE OF INSTITUTIONAL COLLABORATION

Institutional collaboration between community councils, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), and governmental agencies is essential for effective disaster response and climate change adaptation in Mozambique. The country’s legal and strategic frameworks, including the 2020 Disaster Risk Management (DRM) Law, emphasize the need for multisectoral coordination at central, provincial, and district levels. Government bodies such as the National Institute for Disaster Management (INGD), Technical Councils for DRM, and Emergency Operations Centres are responsible for coordinating relief, rehabilitation, and climate resilience initiatives, but their effectiveness is significantly enhanced when they work in close partnership with civil society and community actors. Consultative forums and community engagement plans, as promoted by the Disaster Recovery Framework, ensure that local knowledge and priorities are integrated into recovery and adaptation strategies, while also strengthening transparency, accountability, and participation.

Non-Governmental Organizations and community councils play a critical role in bridging the gap between national policy and local needs, particularly in vulnerable and remote areas. Their involvement in planning, decision-making, and implementation helps tailor interventions to the specific risks and capacities of communities, making disaster response more inclusive and adaptive. Projects such as the Local Climate Adaptive Living Facility (LoCAL) demonstrate how direct funding and participatory planning at the local level can lead to more resilient infrastructure and community-led adaptation initiatives. Furthermore, coordinated efforts among government, NGOs, and international agencies have been shown to improve preparedness, streamline emergency operations, and reduce community vulnerability to natural hazards. In summary, robust institutional collaboration ensures that disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation efforts are more comprehensive, sustainable, and responsive to the needs of Mozambique’s diverse communities.

ENHANCING PUBLIC HEALTH THROUGH NATURE-BASED INFRASTRUCTURE

While grey infrastructure, such as drainage canals, levees, and retention basins, has traditionally been the cornerstone of flood management, there is a growing recognition of the value of nature-based solutions (NbS) as cost-effective and sustainable alternatives. Nature-based solutions—including restored wetlands, mangroves, green roofs, and permeable surfaces—can provide flood protection that rivals or even exceeds that of traditional grey infrastructure, often at lower long-term cost and with added co-benefits such as improved water quality, carbon sequestration, and enhanced biodiversity. A balanced approach that combines both grey and nature-based infrastructure—sometimes referred to as hybrid or green-grey infrastructure—offers the most effective and resilient strategy for managing flood risk in the face of climate change. For example, green infrastructure can reduce the burden on storm drains and levees by absorbing and slowing runoff, while grey infrastructure can provide necessary protection where natural solutions alone are insufficient.

Research and case studies have shown that integrating nature-based solutions into flood management not only reduces damages and costs but also increases community resilience and provides ecosystem services that extend beyond flood risk reduction. Moreover, hybrid approaches can be tailored to local conditions, maximizing both environmental and engineering benefits. In summary, the paradigm is shifting from reliance on grey infrastructure alone toward a more holistic, integrated approach that leverages the strengths of both grey and nature-based solutions for flood management and climate adaptation.

ADDRESSING SOCIOECONOMIC INEQUALITIES AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Climate-related disasters disproportionately affect low-income communities, women, children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. These groups often lack access to adequate housing, healthcare, and early warning systems. In Mozambique, decades of structural poverty and regional disparities (especially in rural areas where 53.88% of Sub-Saharan Africans live) have left many communities with few resources to prepare for or recover from natural hazards. Addressing these disparities is not only a matter of social justice, but also a strategic imperative for improving public health and disaster risk reduction. Research indicates that resilience efforts are most effective when they actively reduce inequality through targeted support mechanisms, such as accessible education and health services.

Beyond the immediate relief response, building long-term resilience requires integrating vulnerable populations into local governance and planning processes. Community councils, when inclusive and representative, can serve as vital platforms for marginalized voices, ensuring that disaster preparedness plans reflect the lived realities of those most at risk. Empowering women and local leaders through participatory decision-making enhances social cohesion and creates trust between citizens and institutions, which are key components of resiliency and recovery. Such approaches transform disaster recovery from a reactive process into a proactive strategy for social equity and sustainable development. Furthermore, climate change has been shown to impact maternal and fetal health, with pregnant individuals facing heightened risks of complications due to extreme heat and other factors. Studies have also highlighted the importance of inclusive disaster risk management and gender equality in building resilience. Finally, addressing the needs of people with disabilities in disaster planning is crucial, as they often face unique challenges during extreme weather events.

INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AND FUNDING

Mozambique’s public health and disaster recovery efforts have been significantly bolstered by international support, including technical assistance, humanitarian aid, and long-term climate adaptation funding. Partnerships with UN agencies, bilateral donors, and international NGOs have enabled the country to implement early warning systems, climate-resilient infrastructure, and localized emergency response mechanisms. These collaborations have not only provided critical financial support but have also introduced best practices and technological innovations that would otherwise be out of reach for local governments. International actors have played a catalytic role in bridging resource gaps and accelerating post-disaster recovery timelines. However, the long-term success of such collaborations depends on building robust institutional frameworks and transparent accountability systems. Funding mechanisms must be aligned with national development strategies and localized priorities to avoid duplication and inefficiency. Moreover, empowering community councils to partner directly with international organizations can facilitate more grounded and effective program implementation. With climate risks expected to increase in frequency and intensity, sustained international engagement, paired with national ownership, is essential for Mozambique to scale its resilience efforts and safeguard vulnerable populations from future shocks.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights the critical role that multi-stakeholder collaborations, especially those involving NGOs, community councils, and governmental agencies, play in enhancing disaster resilience and climate adaptation in Mozambique. The evidence demonstrates that inclusive, participatory models are particularly effective in strengthening community-level preparedness and long-term recovery, especially when targeted toward vulnerable populations such as women, children, and the elderly.

One of the most significant themes to emerge from the literature is the importance of local leadership and ownership. Community councils in Mozambique have proven instrumental in articulating grassroots needs, guiding local adaptation strategies, and coordinating emergency responses. When empowered with decision-making authority and resources, these councils serve as essential bridges between top-down policy directives and the lived realities of at-risk populations. Programs like the Local Climate Adaptive Living Facility (LoCAL) offer compelling evidence that direct support to community structures can yield effective, scalable solutions for both climate and health emergencies.

At the same time, the review underscores several enduring challenges. Despite legal frameworks such as Mozambique’s 2020 Disaster Risk Management Law, coordination across sectors remains uneven. Many government agencies still face resource constraints, personnel shortages, and bureaucratic fragmentation, which can delay or dilute effective implementation. These issues are particularly acute in conflict-affected regions like Cabo Delgado. Moreover, while NGOs and CSOs bring critical expertise and community trust, their efforts are often hampered by funding unpredictability and limited long-term institutional integration. In some cases, international donors prioritize short-term, project-based funding models that may not align with local timelines or priorities. There is a need for more sustained investment in local capacity-building, transparent financial systems, and monitoring mechanisms that ensure alignment with national strategies and international best practices.

Another key insight from this review is the growing recognition of hybrid infrastructure strategies that combine grey and nature-based solutions. Projects in Beira and other urban centers have demonstrated how NbS not only reduce flood risk, but also improve water quality, biodiversity, and social cohesion. This is particularly relevant as Mozambique grapples with increasing climate extremes and urban population growth. Still, scaling NbS requires supportive policy environments, cross-sector expertise, and localized planning frameworks that respect ecological and cultural contexts.

Critically, inclusivity must remain at the center of disaster risk reduction efforts. As the data show, populations already facing socioeconomic marginalization, such as rural women, individuals with disabilities, and informal settlement residents, are often disproportionately affected by both health and climate crises. Successful interventions consistently feature gender-sensitive planning, culturally appropriate communication, and efforts to dismantle structural inequalities in access to healthcare and health information and disease prevention efforts.

Future research should further explore the longitudinal impacts of community-based public health resilience programs, including metrics of sustainability, empowerment, and recovery quality. Evaluating how community councils evolve over time and how institutional partnerships mature will be essential for refining these models. In addition, comparative studies across regions, within and beyond Africa, could help identify replicable strategies and policy innovations.

In summary, this review illustrates that Mozambique’s path to resilience is both complex and promising. The convergence of local leadership, civil society innovation, and international support offers a powerful model for enhancing public health in climate-vulnerable nations. However, success will require continuous adaptation, robust coordination, and a deep commitment to equity at all levels of governance. Mozambique’s recovery and resilience to disasters require a multifaceted approach that integrates local knowledge, innovative technologies, and international cooperation. By promoting public health through strengthening early warning systems, investing in climate-resilient infrastructure, and addressing socioeconomic inequalities, Mozambique can build a more resilient future. The lessons learned from recent disasters provide a foundation for moving forward, but sustained efforts and resources will be needed to achieve long-term success.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the literature review, as well as drafting and editing of the manuscript. Furthermore, all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement:

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement:

Since this study was a secondary data analysis on previously published articles and no human subjects participated, no Institutional Review Board (IRB) review was sought.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References:

- Africa faces disproportionate burden from climate change and adaptation costs. World Meteorological Organization. September 2, 2024. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/africa-faces-disproportionate-burden-from-climate-change-and-adaptation-costs

- IPCC. Chapter 9: Africa. IPCC Sixth Assessment Report: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerabilities. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/chapter/chapter-9/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- UN Office of Disaster Risk Reduction. Disaster Risk Reduction in Least Developed Countries. July 31, 2020. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.undrr.org/implementing-sendai-framework/sendai-framework-action/disaster-risk-reduction-least-developed-countries

- Olu OO. Towards building climate-resilient health systems and communities: a clarion call to increase investments in public health disaster risk reduction in Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2025;10(3):e016232. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2024-016232

- Africa Climate and Health Alliance (ACHA) | Position Statement for COP29. A Light Bulb of Youth In African Development. December 18, 2024. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.theyouthcafe.com/updates/africa-climate-and-health-alliance-acha-position-and-call-to-action-for-cop29

- Henri Aurélien AB. Vulnerability to climate change in sub-Saharan Africa countries. Does international trade matter? Heliyon. 2025;11(4):e42517. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42517

- Baldé T, Billaud A, Beadling CW, Kartoglu N, Anoko JN, Okeibunor JC. The WHO African Region Initiative on Engaging Civil Society Organizations in Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Best Practices and Lessons Learned for a More Effective Engagement of Communities in Responding to Public Health Emergencies. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2023;17:e445. doi:10.1017/dmp.2023.99

- World Health Organization. Community Assets and Civil Society Outreach in Critical Times: An Initiative to Engage Civil Society Organizations in the COVID-19 Response. 1st ed. World Health Organization; 2022. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/362782/9789240055070-eng.pdf

- Ventura L. Poorest Countries in the World 2024. Glob Finance Mag. Published online May 6, 2024. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://gfmag.com/data/economic-data/poorest-country-in-the-world/

- World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/

- Environment and Emergencies | Topics | ReliefWeb. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://reliefweb.int/topic/environment-and-emergencies

- Club Mozambique. Flood on Save river worsens. Mozambique. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://clubofmozambique.com/news/flood-save-river-worsens-mozambique/

- Flood recovery and mangrove reforestation in Mozambique. Nature-based Solutions Initiative. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.naturebasedsolutionsinitiative.org/news/flood-recovery-and-mangrove-reforestation-in-mozambique/

- Climate Resilient Infrastructure Development Facility (CRIDF). Case Study: Limpopo River Basin. Published online 2018. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://cridf.net/RC/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/P2537_CRIDF_CS_LIMPOPO_WEB_v5.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Ryan Truscott. Deforestation seen as aggravating Zimbabwe, Mozambique flood crisis. RFI. April 7, 2019. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20190407-deforestation-seen-aggravating-zimbabwe-mozambique-flood-crisis

- Philip Kleinfeld. Mozambique cyclone victims face bleak resettlement prospects. New Humanit. Published online December 10, 2019. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2019/12/10/Mozambique-Cyclone-Idai-Resettlement-climate-change

- Early Warning System Saves Lives in Mozambique. World Bank. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2023/09/11/early-warning-system-saves-lives-in-afe-mozambique

- World Bank. Disaster Risk Profile: Mozambique. Published online 2019. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://www.gfdrr.org/sites/default/files/publication/mozambique_low.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Club Mozambique. Mozambique: Cyclones increasing in number, winds stronger – report. Mozambique. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-cyclones-increasing-in-number-winds-stronger-report-279141/

- UNICEF. Cyclone Idai and Kenneth |UNICEF Mozambique. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.unicef.org/mozambique/en/cyclone-idai-and-kenneth

- Falconer R. Freddy, “longest-lasting” tropical cyclone, to hit Mozambique for 2nd time as Category 3 storm. Axios. March 9, 2023. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.axios.com/2023/03/08/cyclone-freddy-longest-lasting-record

- Mozambique: Tropical Cyclone Freddy, Floods and Cholera – Situation Report No.2 – Mozambique | ReliefWeb. April 22, 2023. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://reliefweb.int/report/mozambique/mozambique-tropical-cyclone-freddy-floods-and-cholera-situation-report-no2

- Mozambique Response Plan: Cyclone Freddy, Floods & Cholera (March – September 2023) | Mozambique (emergency) | Humanitarian Action. October 30, 2023. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://humanitarianaction.info/plan/1153/article/mozambique-response-plan-cyclone-freddy-floods-cholera-march-september-2023

- The Faster Mozambique Rebuilds After Cyclones, the Better it Limits Their Devastating Impact on the Economy. World Bank Blogs. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/nasikiliza/faster-mozambique-afe-rebuilds-after-cyclones-better-it-limits-their-devastating-impact

- Civil Society Organizations. UNDP. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.undp.org/partners/civil-society-organizations

- Panos A, Panos P. The Importance of Non-Governmental Organizations in Response to the Corona Virus Pandemic in Rural Mozambique: A Case Study. Med Res Arch. 2024;12(10). doi:10.18103/mra.v12i10.5910

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund for the World Health Organization Impact Report July 1 to September 30, 2020. Published online 2020. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://www.swissphilanthropy.ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Solidarity-Respond-Fund-Impact-Report-Oct.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Panos P, Panos A. The Aftermath of Covid and Cyclones Idai and Kenneth: A Naturalistic Experiment Examining Empowerment and Resiliency in Rural Mozambique. Res Soc Work Pract. 2023;33(5):544-561. doi:10.1177/10497315221117547

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund- Collective Action for a Safer World: Final Report. Published online 2024. Accessed May 18, 2024. https://who.foundation/uploads/WHO-Foundation-COVID-19-SRF-Report.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Panos A, Panos P, Gerritsen-McKane R, Tendai T. The Care for Life Family Preservation Program: Outcome Evaluation of a Holistic Community Development Program in Mozambique. Res Soc Work Pract. 2020;30(1):84-96. doi:10.1177/1049731519844324

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19 doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In: JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. doi:10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

- UN Capital Development Fund. Using the LoCAL approach for locally led action to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic in Mozambique. Accessed May 16, 2025. http://www.uncdf.org/article/6916/using-the-local-approach-for-locally-led-action-to-tackle-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-mozambique

- Guimarães Nobre G, Towner J, Nhantumbo B, et al. Ready, Set & Go! An anticipatory action system against droughts. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci. 2024;24(12):4661-4682. doi:10.5194/nhess-24-4661-2024

- Anticipatory Action for climate shocks | World Food Programme. March 24, 2025. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.wfp.org/anticipatory-actions

- Meurer M, Rodríguez A, Ntunduatha J, Salas A, Teles E. Confronting Climate Change in the Margins: An Ethnographic Explorations of Local Resilience Strategies. Margens. 2024;18(30):62. doi:10.18542/rmi.v18i30.17115

- Kai G, Van Niekerk D. Application of African Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Practices for Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management for Policy Formulation. Published online July 14, 2023. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4510063

- International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI). Navigating the climate crisis: Insights from Beira, Mozambique – CityTalk. June 1, 2024. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://talkofthecities.iclei.org/navigating-the-climate-crisis-insights-from-beira-mozambique/

- Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN). Adaptation Brief: Mozambique – Cities and Climate Change Project (3CP). Published online 2023. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://gain.nd.edu/assets/565162/nd_gain_adaptation_brief_mozambique.pdf

- Spekker H, Kleinefeld B. Climate Change Adaptation Strategies in Developing Countries – Exemplary Flood and Erosion Protection Projects in Mozambique. In: Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas. Springer; 2017:151-164.

- Cottam B. Africa’s nature-based solutions to tackle climate change. Geographical. April 24, 2025. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://geographical.co.uk/news/africas-nature-based-solutions-to-tackle-climate-change

- In Mozambique, climate resilient infrastructures save lives and reduce the impact from natural disasters | UN-Habitat. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://unhabitat.org/news/28-mar-2023/in-mozambique-climate-resilient-infrastructures-save-lives-and-reduce-the-impact

- Mozambique: Building resilience through green-gray infrastructure | PreventionWeb. February 3, 2022. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.preventionweb.net/news/building-resilience-through-green-gray-infrastructure-lessons-beira

- Muradás P, Puig M, Ruiz Ó, Solé JM. Mainstreaming Climate Adaptation in Mozambican Urban Water, Sanitation, and Drainage Sector. In: Oguge N, Ayal D, Adeleke L, Da Silva I, eds. African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation. Springer International Publishing; 2021:2631-2652. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-45106-6_132

- Ministry of Land and Environment. Mozambique National Adaptation Plan. Published online March 15, 2023. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/National_Adaptation_Plan_Mozambique.pdf

- Bratley K, Meyer-Cirkel A. Understanding Agricultural Output in Mozambique – Using remote sensing to initiate a discussion. Published online 2025. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2025/English/wpiea2025009-print-pdf.ashx

- Amanda de Albuquerque, Andrew Hobbs. Challenges and Opportunities for Efficient Land Use in Mozambique: Taxes, Financing, and Infrastructure. Climate Policy Initiative (CPI). Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/challenges-opportunities-efficient-land-use-mozambique-taxes-financing-infrastructure/

- Improved post-harvest handling raises incomes for Mozambique farmers. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Accessed May 16, 2025. http://www.fao.org/in-action/improved-post-harvest-handling-raises-incomes-for-mozambique-farmers/en/

- Zorrilla-Miras P, Lisboa SN, López-Gunn E, Giordano R. Farmers’ information sharing for climate change adaptation in Mozambique. Inf Dev. Published online February 12, 2024:02666669241227910. doi:10.1177/02666669241227910

- Lumbroso D, Ramsbottom D, Spaliveiro M. Sustainable flood risk management strategies to reduce rural communities’ vulnerability to flooding in Mozambique. J Flood Risk Manag. 2008;1(1):34-42. doi:10.1111/j.1753-318X.2008.00005.x

- Rrokaj S, Molinari D, Paz Idarraga CD, et al. Flood risk assessment and participative process in the data-scarce Metuge district of Mozambique: An exportable approach. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025;116:105163. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.105163

- Gomes C, Schmidt L. Cabo Delgado, Mozambique: Beyond Climate—How to Approach Resilience in Extremely Vulnerable Territories? In: Campello Torres PH, Jacobi PR, eds. Towards a Just Climate Change Resilience. Palgrave Studies in Climate Resilient Societies. Springer International Publishing; 2021:65-79. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-81622-3_5

- Mozambique—Community Resilience Program (Tuko Pamoja) · DAI: International Development. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.dai.com/our-work/projects/mozambique-community-resilience-program-tuko-pamoja

- Mozambique Climate Resilience Program. IDH – the Sustainable Trade Initiative. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.idhsustainabletrade.com/project/mozambique-climate-resilience-program/

- Institute For Security Studies. Climate, conflict and aid: three-pronged solution needed for Mozambique | ISS Africa. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20241001125636/https://issafrica.org/iss-today/climate-conflict-and-aid-three-pronged-solution-needed-for-mozambique

- Cavane EP, Uqueio JV, Sitoe A. Adapting to Climate Change: Emerging Local Institutions in Mozambique. Published online 2025. doi:10.2139/ssrn.5249366

- Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) – The World Bank. Mozambique: Promoting the Integration of Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation Into District Development Plans and Community-Based Risk Management | GFDRR. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.gfdrr.org/en/mozambique-promoting-integration-disaster-risk-reduction-and-climate-change-adaptation-district

- AGGRC P. Gender Analysis in Disaster Risk Management in Mozambique | Policy Brief. Plateforme AGGRC. May 16, 2025. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.arc.int/gender-drmp/gender-analysis-in-disaster-risk-management-in-mozambique-policy-brief.html

- World Bank. Early Warning System Saves Lives in Mozambique. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2023/09/11/early-warning-system-saves-lives-in-afe-mozambique

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Disaster Recovery in Mozambique. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://disasterlaw.ifrc.org/sites/default/files/media/disaster_law/2023-05/Disaster%20Recovery%20in%20Mozambique%20%28Final%29.pdf

- Donkor FK, Mearns K. Harnessing Indigenous Knowledge Systems for Enhanced Climate Change Adaptation and Governance: Perspectives from Sub-Saharan Africa. In: Ebhuoma EE, Leonard L, eds. Indigenous Knowledge and Climate Governance. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Springer International Publishing; 2022:181-191. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-99411-2_14

- World Bank. Mozambique Disaster Risk Management and Resilience Program. Published online 2021. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P166437

- Government of Mozambique. Disaster Risk Management Law No. 10/2020. Bol Repúb. 2020;1(104):1-15.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Disaster Risk Reduction in Mozambique: Status Report 2022. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.undrr.org/publication/disaster-risk-reduction-mozambique-status-report-2022

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Institutional assessment. In: Mozambique Floods 2000: Lessons Learned. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2003. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.fao.org/4/ae079e/ae079e06.htm

- World Bank. Mozambique Disaster Recovery Framework. Published online 2017. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/924371468186846675/mozambique-disaster-recovery-framework

- UN Capital Development Fund. LoCAL Mozambique. Mozambique. Accessed May 17, 2025. http://uncdf-staging.icentric-dev.com/local/mozambique

- UN Capital Development Fund. Mozambique Expands Locally-Led Climate Resilience, with support from the European Union. Accessed May 17, 2025. http://www.uncdf.org/article/8187/mozambique-expands-locally-led-climate-resilience-with-support-from-the-european-union

- Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN). Adaptation Brief: Mozambique – Cities and Climate Change Project (3CP). Published online 2023. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://gain.nd.edu/assets/565162/nd_gain_adaptation_brief_mozambique.pdf

- Esraz‐Ul‐Zannat Md, Dedekorkut‐Howes A, Morgan EA. A review of nature‐based infrastructures and their effectiveness for urban flood risk mitigation. WIREs Clim Change. 2024;15(5):e889. doi:10.1002/wcc.889

- Beker SA, Khudur LS, Krohn C, Cole I, Ball AS. Remediation of groundwater contaminated with dye using carbon dots technology: Ecotoxicological and microbial community responses. J Environ Manage. 2022;319:115634. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115634

- ProFor. Upscaling Nature-Based Flood Protection in Mozambique’s Coastal Cities. June 16, 2024. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.profor.info/index.php/knowledge/upscaling-nature-based-flood-protection-mozambique%25E2%2580%2599s-coastal-cities

- Inan E. Nature-based solutions to reduce the risk of flooding in Mozambique. PIROI – Plateforme d’Intervention Régionale de l’Océan Indien. September 13, 2023. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://piroi.croix-rouge.fr/des-solutions-fondees-sur-la-nature/

- World Bank. Upscaling Nature-Based Flood Protection in Mozambique’s Cities: Enabling Environment. Published online 2020. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/612051585284647951/pdf/Upscaling-Nature-Based-Flood-Protection-in-Mozambique-s-Cities-Enabling-Environment.pdf

- World Bank. Upscaling Nature-Based Flood Protection in Mozambique’s Cities: Urban Flood and Erosion Risk Assessment and Potential Nature-Based Solutions for Nacala and Quelimane (English). Published online January 1, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://naturebasedsolutions.org/knowledge-hub/32-upscaling-nature-based-flood-protection-mozambiques-cities-urban-flood-and-erosion

- Mozambique – Upscaling nature-based flood protection in Mozambique’s cities: Lessons learnt from Beira | PreventionWeb. April 7, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/mozambique-upscaling-nature-based-flood-protection-mozambiques-cities-lessons-learnt

- Macamo M. After Idai: Insights from Mozambique for Climate Resilient Coastal Infrastructure. Published online 2021. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Policy-Insights-110-macamo.pdf

- World Bank. Inclusive Disaster Risk Management and Gender Equality. 2022. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.gfdrr.org/en/inclusive-drm

- José Maria do Rosário Chilaúle Langa, Natacha Bruna, Boaventura Monjane, Giverage do Amaral, et al. Extreme Climatic Events and Climate Change Policies A Call for Climate Justice Action in Mozambique. In: Climate Justice in the Majority World. 1st ed. Routledge; 2023:42-60. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003214021-3/extreme-climatic-events-climate-change-policies-jos%C3%A9-maria-ros%C3%A1rio-chila%C3%BAle-langa-natacha-bruna-boaventura-monjane-giverage-amaral-elton-augusto-da-am%C3%A9lia-f%C3%A9-bento-paulo-rafael-patricia-figueiredo-walker-patricia-perkins

- Leave No One Behind | Human Rights Watch: People with Disabilities and Older People in Climate-Related Disasters. Human Rights Watch; 2022. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/11/07/leave-no-one-behind

- Rural population, percent in Sub Sahara Africa. TheGlobalEconomy.com. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/rural_population_percent/Sub-Sahara-Africa/

- World Bank. Mozambique Poverty Assessment: Strong but Not Broadly Shared Growth. Published online 2018. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/248561541165040969/pdf/Mozambique-Poverty-Assessment-Strong-But-Not-Broadly-Shared-Growth.pdf

- UNICEF. Multidimensional Child Poverty in Mozambique. Published online 2020. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.unicef.org/esa/media/9311/file/UNICEF-Mozambique-Child-Poverty-Report-2020.pdf

- OECD. Reducing Inequalities by Investing in Early Childhood Education and Care. Published online 2025. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/reducing-inequalities-by-investing-in-early-childhood-education-and-care_b78f8b25-en.html

- UN Office of Disaster Risk Reduction. Inclusive disaster risk reduction means resilience for everyone. May 30, 2023. https://www.undrr.org/news/inclusive-disaster-risk-reduction-means-resilience-everyone

- UN Office of Disaster Risk Reduction. Women’s Leadership and Women’s International Network on Disaster Risk Reduction (WIN DRR). Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.undrr.org/gender/womens-leadership

- World Bank. Community Participation and Citizen Engagement. Published online 2022. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.gfdrr.org/en/citizen-engagement

- Shah S. Climate Change Can Increase Health Risks During Pregnancy. TIME. May 14, 2025. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://time.com/7285515/climate-change-impact-healthy-pregnancy/

- Promoting women’s leadership in Disaster Risk Reduction and resilience. UN Women – Headquarters. May 31, 2019. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2019/5/news-promoting-womens-leadership-in-disaster-risk-reduction-and-resilience

- Engelman A, Craig L, Iles A. Global Disability Justice In Climate Disasters: Mobilizing People With Disabilities As Change Agents. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(10):1496-1504. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00474

- Multi-hazard early warning systems in Mozambique | UNDRR. November 14, 2024. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://www.undrr.org/resource/case-study/multi-hazard-early-warning-systems-mozambique

- Mozambique: Strengthening Disaster Risk Management and Building Climate Resilience | GFDRR. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://www.gfdrr.org/en/mozambique-strengthening-disaster-risk-management-and-building-climate-resilience

- UNDP, KOICA, and INGD Strengthen Climate Resilience and Social Cohesion in Central and Northern Mozambique. UNDP. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://www.undp.org/mozambique/press-releases/undp-koica-and-ingd-strengthen-climate-resilience-and-social-cohesion-central-and-northern-mozambique

- Navarro Casquete C. Disaster Recovery in Mozambique: A Legal and Policy Survey. Published online 2022. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://disasterlaw.ifrc.org/sites/default/files/media/disaster_law/2023-05/Disaster%20Recovery%20in%20Mozambique%20%28Final%29.pdf

- IOM. Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://mozambique.iom.int/disaster-risk-reduction-and-climate-change-adaptation