Substance Use in LGB Individuals: Trends and Implications

Use of Alcohol, Nicotine, and Drugs in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Persons: Implications for Substance Use Disorders among Sexual Minorities

Ellis Jang, Johnson Thai1, Thien Nguyen1, Ashim Malhotra2, Jose L. Puglisi1

- College of Medicine, California Northstate University, 9700 West Taron Drive, Elk Grove, 95757, CA.

- College of Pharmacy, California Northstate University, 9700 West Taron Drive, Elk Grove, 95757, CA.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 28 February 2025

CITATION: Jang, E., Thai, J., et al., 2025. Use of Alcohol, Nicotine, and Drugs in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Persons: Implications for Substance Use Disorders among Sexual Minorities. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(2). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i2.6351

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i2.6351

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and other sexual and gender minorities face heightened risks of substance abuse compared to heterosexual individuals due to immediate and long-term stressors. Furthermore, the added stressors of isolation and lockdown during the pandemic increased substance use and abuse as a way of coping with anxiety concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. This study assesses substance use trends in the sexual minority population from 2015 to 2021.

Method: We analyzed datasets from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health to evaluate alcohol use disorders, cannabis use disorders, nicotine dependence, and self-reported drug abuse between lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals and heterosexual individuals, including youth (ages twelve to twenty-five) and adult (ages twenty-six and older) subgroups. Chi-square tests were performed with a p-value less than 0.05.

Results: With an average of three thousand two hundred fifty-three lesbian, gay, and bisexual respondents and thirty-six thousand eight hundred ninety-three heterosexual respondents, lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals exhibited significantly higher rates of alcohol use disorders, cannabis use disorders, nicotine dependence, and drug misuse compared to heterosexual individuals. Adult lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals and heterosexual individuals demonstrated higher rates of nicotine dependence, while youth predominated in higher rates of other substance use disorders. All values were statistically significant with a p-value less than 0.001.

Conclusions: Both sexual minority youth and adults demonstrated disproportionately higher rates of substance abuse compared to the sexual majority. In addition, this study provided an opportunity to measure drug use in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which highlighted the effectiveness of opioid use countermeasures versus an increase in illicit drug use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. These findings emphasize the need for treatment programs tailored for sexual and gender minorities, with a focus on the substances most prevalent in this population, and the importance of addressing these issues earlier in life.

Keywords

substance use, LGBTQIA+, alcohol use disorder, nicotine dependence, cannabis use disorder, drug abuse

Introduction

The United States Department of Health and Human Services and Office of Disease and Health Promotion articulates a national goal to improve the health and well-being of sexual minorities in the Healthy People 2030 initiative. Members of the LGBTQIA+ community are more susceptible to health problems, such as substance use, mental health disorders, unprotected sex and sexually transmitted diseases, cancer-related risk behaviors, self-harm, and bullying. The disproportionately higher rates of substance use, specifically, in this population has largely been examined in a two-fold manner: (1) stress from discrimination and stigma that may drive LGBTQIA+ individuals to use alcohol, nicotine, and other substances to cope, and (2) lack of culturally competent health care services. The minority stress model postulates that proximal stressors (i.e., intrapersonal) like self-stigma and distal stressors (i.e., interpersonal and structural) like discriminatory laws and policies predispose members of the LGBTQIA+ community to higher incidences of substance abuse compared to the sexual majority. Furthermore, peer substance use may also influence substance use patterns in the LGBTQIA+ community. Drinking plays a central role in lesbian- and gay-friendly social environments. Gay bars, for instance, remain one of the main social outlets in LGBTQIA+ communities, with groups of homosexual and bisexual women and men spending more time than heterosexual individuals in heavier drinking contexts. Moreover, illicit drug use has also been linked to drug-enhanced sexual experiences and sexual identity exploration. In the past decade, interventions like alcohol advertising restrictions and opioid prescription guidelines have been implemented to mitigate substance abuse and the drug overdose epidemic. Yet, substance abuse treatment and health services tailored to LGBTQIA+ individuals remain limited.

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic caused substantial disruptions to daily life in unprecedented ways. In-person substance use disorder treatment was limited, with many services moving to digital and telehealth delivery. The pandemic disturbed the healthcare delivery system, aggravating the already existing problems with substance abuse treatment availability and accessibility, such as for individuals from urban slum populations. Sexual minority young adults were especially vulnerable to substance abuse due to school shutdowns and isolation from affirming support systems. The added stressors of isolation and lockdown increased substance use/abuse as a way of coping with anxiety concerning COVID-19, leading to an exponential increase in substance use and related overdose deaths during the pandemic.

This paper evaluates abuse of alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, opioids, prescription medications, and illicit drugs in the lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) community from 2015 to 2021, a period of national reform for sexual minorities (e.g., legalization of same-sex marriage) met with new stressors provoked by the COVID-19 pandemic. We aim to provide an overview of the current landscape on substance abuse in the LGBTQIA+ community, including the substances commonly abused, the factors that contribute to substance abuse in this population, and the challenges of providing treatment to LGBTQIA+ individuals with substance abuse issues.

Methods

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data sets from 2015 to 2021 were analyzed. It entails a nationwide study that provides data on the level and patterns of alcohol, nicotine, and substance use in the United States. Directed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), an agency in the United States Department of Health and Human Services, NSDUH interviews approximately 70,000 people aged 12 and older annually. The questionnaire underwent a partial redesign in 2015 to improve the quality of the NSDUH data and to address the changing needs of policymakers and researchers regarding substance use and mental health issues, which included the addition of sexual attraction and sexual identity questions.

VARIABLE PARAMETERS

Out of the 2,679-2,890 variables included in the survey, 147 were selected to determine substance use. Participants were divided into LGB, if they identified their sexual identity as lesbian, gay, or bisexual and grouped as sexual minorities, or Hetero if they identified as heterosexual. We used DSM-5 criteria and related variables to define alcohol and marijuana use disorders. For the years 2015 to 2019, 15 variables pertaining to alcohol use disorder and 14 variables pertaining to cannabis use disorder were used in our inclusion criteria. From 2019 onwards, a new variable was added to the survey and used for our inclusion criteria for alcohol and marijuana. Likewise, nicotine use disorder was pre-defined by one variable from 2015 to 2021 with questions pertaining to dependence based on criteria from the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS) and the Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependent (FTND). For misuse of prescription opioids (hydrocodone, oxycodone, tramadol, codeine, morphine, fentanyl, buprenorphine, oxymorphone, demerol, hydromorphone, and methadone) and prescription non-opioids (prescription pain relievers, prescription tranquilizers, prescription stimulants, and prescription sedatives), the inclusion criterion was to have reported misuse in the past year to any of the respective prescription drugs. For illicit drug use (cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, methamphetamine), the inclusion criterion was to have reported use in the past year to any of the above listed.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We used the IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0 software to analyze the datasets. The DSM-5 criteria for alcohol and cannabis use disorders, nicotine dependence per the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale and Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence, and self-reported drug abuse (e.g. prescription opioid misuse, prescription drug misuse other than opioids, and illicit drug use) were used to evaluate for statistically significant differences in SUDs and substance abuse between lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) and heterosexual groups, including youth (age 12-25) and adult (age 26+) subgroups. Chi-square tests with a p-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

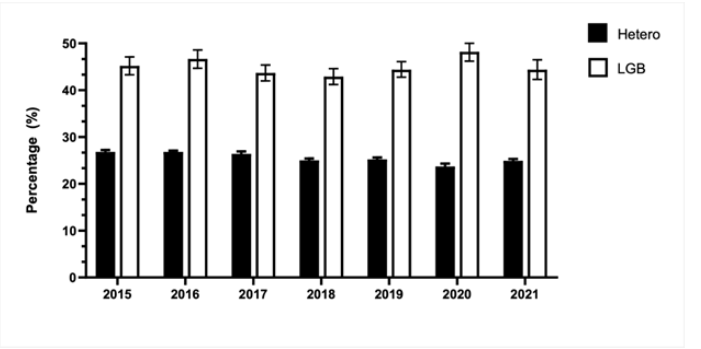

With an average of 3,253 LGB and 36,893 heterosexual survey respondents from 2015 to 2021, 25.5 ± 1.0% of sexual minority population misused at least one or more substances compared to 45.1 ± 1.7% of LGB (p < 0.001), a nearly two-fold increase.

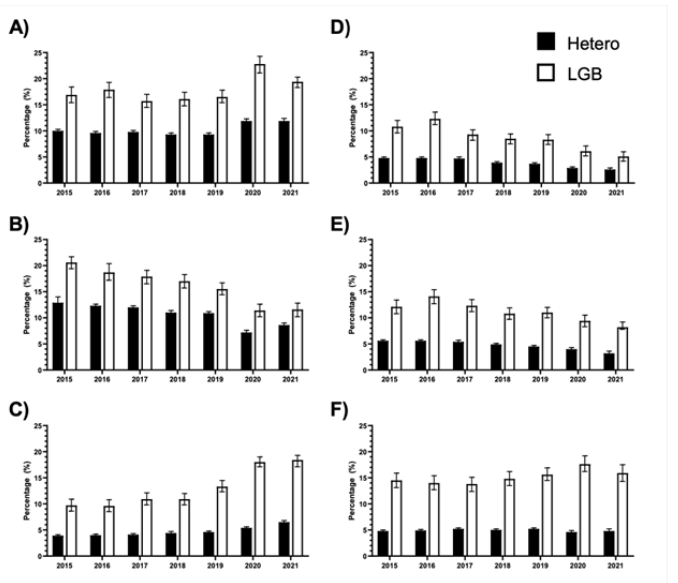

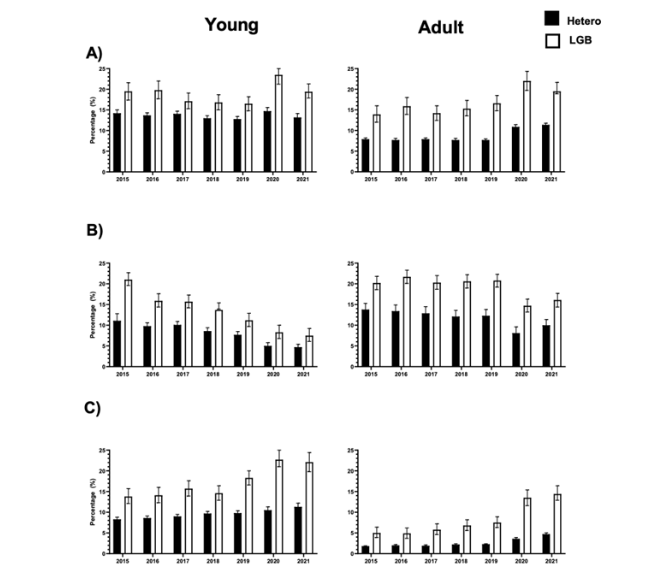

Youth LGB and heterosexual individuals had higher rates of alcohol use disorder (AUD), cannabis use disorder (CUD), prescription drug misuse, and illicit drug use compared to their adult counterparts. LGB had significantly higher rates of AUD (17.9% vs 10.3%), nicotine dependence (16.1% vs 10.7%), and CUD (13.0% vs 4.7%) compared to the heterosexual group.

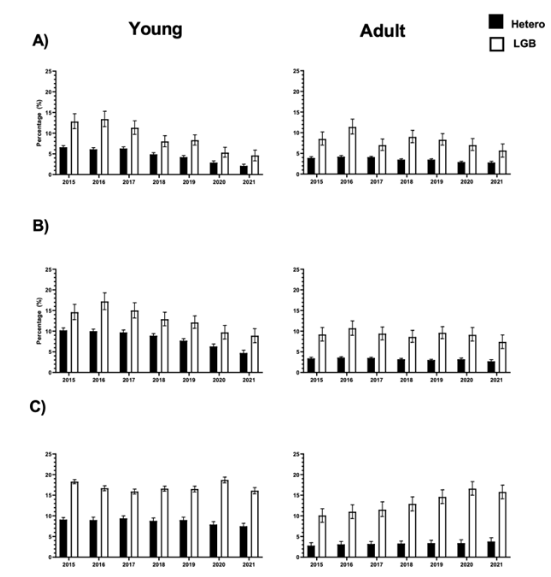

Similarly, in terms of drug use, LGB had significantly higher rates of prescription opioid misuse (8.6% vs 3.9%), prescription drug misuse besides opioids (11.1% vs 4.7%), and illicit drug use (15.2% vs 4.9%).

Overall, there was a decreasing trend in the percentage of nicotine dependence in both the heterosexual and LGB community from 12.9% to 8.6% for heterosexuals and 20.6% to 11.6% in LGB. Heterosexual (13.6%) and LGB (18.9%) youth had higher rates of AUD compared to their adult counterparts (Hetero 8.7% and LGB 16.8%, respectively). Amongst youth, LGB youth had higher rates of AUD compared to Hetero youth (18.9% vs 13.6%).

Similar trends were observed for CUD and drug use. Adult heterosexual (11.8%) and LGB (19.2%) individuals had higher rates of nicotine dependence compared to their youth counterparts (Hetero 8.1% and LGB 13.3%, respectively). Amongst youth, LGB youth had higher rates of nicotine dependence compared to Hetero youth (13.3% vs 8.1%).

Discussion

This study compared substance use between the LGB population and the sexual majority from 2015 to 2021, revealing that the former have higher rates of substance use compared to the latter, in addition to LGB youth having higher rates compared to LGB adults (with the exception of nicotine). Overall, per year, over 6 years, substance abuse was more prevalent in both the adult and youth LGB groups when compared with the heterosexual comparator groups. Many factors may explain these disparities evident in our data analysis, including but not limited to, social, psychological, and environmental factors that are not mutually exclusive of one another.

The finding that the LGB population has higher overall rates of substance use disorders and drug misuse compared to the sexual majority was unsurprising not only because stigmatization and discrimination of LGBTQIA+ identities may lead to mental health concerns and poor coping mechanisms, but also because LGBTQIA+ affirming spaces including social environments and their accompanying culture often have higher incidences of substance use. This study was designed to analyze substance classes individually (e.g., alcohol use disorder, prescription opioid misuse, illicit drug use, etc.) to further stratify this well-established fact, and thus contributes to the novelty of our findings in the LGBTQIA+ substance use landscape, especially because this dichotomy of substance use as a response to both stress and recreation/culture is important to acknowledge in understanding drug use trends of sexual minorities. Still, more predictors of substance misuse in the LGBTQIA+ population need to be studied to gain a comprehensive understanding. For example, perceived norms of substance use within a community may shape behavior as a study has shown that perceived drug use is higher than actual drug use among LGBTQIA+ individuals, therefore, even perception may act as a reliable predictor of current and future substance use.

Furthermore, when disaggregating the LGB population into youth and adult counterparts, we found that LGB youth had higher rates of substance use compared to LGB adults. This may be a result of LGBTQIA+ adults having a better sense of security in their sexual minority status compared to LGBTQIA+ youth. This stems from the idea that LGBTQIA+ adults are likely to have more autonomy over their environments compared to youth, whether that be seeking social support or the capacity to escape from discrimination. Additionally, LGBTQIA+ adults likely have had more time to process and cope with their identities, and in doing so have developed more mature coping strategies compared to LGBTQIA+ youth.

In contrast, LGBTQIA+ youth have less access to identity-affirming spaces not only because of lack of autonomy but also because of the social isolation mandated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Many LGBTQIA+ youth, especially if living in an environment unsupportive of their sexual identity, relied on school to access mental health services or supportive social networks. Without these resources, LGBTQIA+ youth are more likely to turn to substance abuse as a coping mechanism, which was especially concerning during the COVID-19 pandemic when the illicit drug supply became more toxic, potent, and unpredictable. This is further supported by our analysis, which revealed an increase in illicit drug use among LGB youth versus a decline in use among heterosexual youth in 2020. This increased trend in substance use in 2020 specifically was observed in our analysis of illicit drug use and alcohol use disorder. For illicit drug use, this trend was only evident in LGB youth and adults while heterosexual youth and adults experienced a decline in use in 2020. This disparity likely speaks on how the LGBTQIA+ population was especially negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in the setting of social isolation and limited healthcare resources during this time. LGBTQIA+-identifying individuals already face an additional barrier accessing basic health services due to fear of disclosing or dealing with the discrimination of their sexual identities; thus, the COVID-19 pandemic as an additional barrier can make access to medications difficult and prompt illicit drug use as an alternative (e.g., heroin use in lieu of prescription opioids). For alcohol use disorder, both LGB and heterosexual groups demonstrated an increase in prevalence in 2020. Given that both groups were affected, this likely speaks on the popularity of alcohol in response to mental stressors, a trend well-established in literature especially during the pandemic.

Interestingly, our data analysis revealed a consistent decrease in opioid abuse from 2015 through 2021 across both populations as well as their youth and adult counterparts. This is likely due to the significant strides made in addressing the opioid crisis in the United States, which includes increased use of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder, specific prescribing guidelines established by the CDC, and the establishment of prescription drug monitoring programs in almost every state. The fact that the downward trend in opioid abuse was unaffected by the COVID-19 pandemic speaks to the strength and sustainability of the current efforts made to combat the opioid crisis. Still, more LGBTQIA+ targeted efforts are necessary to close the disparity between opioid misuse in the sexual majority and minority population.

Our study also revealed a decrease in nicotine dependence from 2015 through 2021 across all groups. When disaggregating adult versus youth data, we found that there were higher rates of nicotine dependence in adults compared to youth in both heterosexual and LGB populations. This likely speaks on the success of public health initiatives in deterring youth from tobacco use. Interestingly, the overall downward trend in nicotine dependence was juxtaposed by an increase in rates of marijuana use disorder across all groups in the same time period. Given that both substances are commonly ingested in the same way (i.e. smoking), there is reason to believe these concurrent yet opposite trends are not mutually exclusive, and that marijuana may even serve as a substitute for nicotine consumption. Given that the adverse effects of nicotine are well established versus the lower perceived risk of marijuana consumption, marijuana has been described as generating nicotine-related health benefits. Yet, the federal law continues to recognize marijuana as an illicit drug given uncertainty surrounding long term health effects as well as potential perpetuation of drug-seeking behaviors in the general population. More studies are required surrounding the effects of marijuana on health status and drug behaviors after the implementation of recreational marijuana laws given the rising popularity of marijuana.

Overall, the novelty of our study is a comprehensive look at substance use in the LGB community as a function of time compared to the heterosexual population as well as the disaggregation of drug use between youth and adults, which allowed us to examine changing trends in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the strength of existing public health interventions. Given that self-reported substance misuse and prevalence of substance use disorders were significantly higher among LGB compared to the sexual majority and LGB youth when compared with LGB adults from 2015 to 2021, it is clear that there needs to be greater priority in the LGBTQIA+ population and drug and alcohol use in adolescents as part of the Healthy People 2030 initiative and objectives. Our findings postulate that the disparity in substance use in the LGBTQIA+ and heterosexual community likely stems from risk factors and predictors unique to the LGBTQIA+ community that should continue to be elucidated in further studies, and that changes in substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic may result from changing motives or the exacerbation of risk factors for drug consumption. With the identification of LGBTQIA+-specific risk factors and predictors, future studies may better determine not only how to better provide access to treatment, but how to mitigate the root of substance use in the first place.

Considering that a priority focus of the United States Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2030 plan was to ameliorate drug dependency, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse among LGBTQIA+ youth, our results demonstrate a prominent anathema since the self-reported substance abuse in our dataset is significantly higher among LGBTQIA+ youth when compared with LGBTQIA+ adults.

Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into substance use trends among the LGB population compared to the sexual majority from 2015 to 2021, it is important to acknowledge several potential limitations. First, the data relies on self-reported survey responses which can introduce response bias and social desirability bias, potentially leading to underreporting or overreporting of substance use behaviors. Additionally, the study does not take into account the intersectionality of identities within the LGBTQIA+ population, such as race, ethnicity, education level, and socioeconomic status, which may influence the substance use patterns we examined in our study. Furthermore, there is an absence of a qualitative component, which could have provided a more nuanced understanding of the motivations and contextual factors driving substance use trends in these populations. This study predominantly examines trends within the United States, and the findings do not generalize to other countries or regions with different social and healthcare systems. The COVID-19 pandemic is a significant contextual factor in this study, but the research does not explore the complex interplay between pandemic-related stressors, changes in substance use behaviors, and evolving access to support services. In addition, the 2020 NSDUH had differences in its data collection period, survey mode, and response rates that should be considered when comparing trends from prior years. Lastly, the study identifies disparities in substance use but does not directly elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving these disparities. Future research should consider conducting qualitative interviews and exploring specific social, psychological, and environmental factors that contribute to the observed substance use trends among LGBTQIA+ individuals and their youth.

Conclusion

This study showed higher rates of substance use disorders and misuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals compared to heterosexual individuals, highlighting a significant health disparity for this population. This trend is significantly alarming when comparing substance use dependence between LGBTQIA+ youth and adults, which is antithetical to the Health People 2030 plan. Addressing the social determinants of health that contribute to the health disparities faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals, such as discrimination, stigma, and lack of social support, is crucial to improving the health and well-being of the LGBTQIA+ community. Healthcare providers and organizations that serve LGBTQIA+ populations should tailor their treatments and prevention strategies to better meet the specific needs of this higher-risk population. In addition, our data analysis from 2020 to 2021 helps to evaluate the strength of current drug use countermeasures, as it provides a unique opportunity to measure drug use against the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given that opioid use continued to decline in this period, versus how illicit drug use sharply increased in 2020 among LGB youth compared to a decline in heterosexual youth, we highlight the specific substances that should be emphasized in future programs and anti-substance campaigns. Finally, the substance use in LGBTQIA+ youth is alarming and emphasizes how programs should target youth earlier in the life course for prevention.

Conflict of Interest:

None.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

None.

Definitions and Disclaimers

LGBTQIA+ is an abbreviation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, asexual, and more. The acronym has inclusion of diverse gender and sexual identities has expanded (Blakemore, 2021). An alternative term such as sexual minority is also often used to describe the population.

This paper references journal publications, articles, and other sources that use different variations of the acronym (e.g., LGB, LGBTQ, LGBTQ+, LGBTQ2, etc.). The authors of this paper used the acronym LGB when referencing data points from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health because the database only asked participants to identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual. There was no option to select transgender, queer or questioning, or other identities. The authors of this paper used the acronym LGBTQIA+ to be inclusive while also recognizing that it may not be and continues to be expanded upon.

References:

- Krueger, E., et al. Changes in sexual identity and substance use during young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2022; vol. 241, p. 109674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109674.

- Rodríguez-Bolaños, R., et al. Similarities and differences in substance use patterns among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual Mexican adult smokers. LGBT Health. 2021; vol. 8, no. 8, pp. 545-553. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2020.0457.

- Quinn, G., et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and Queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2015; vol. 65, no. 5, pp. 384-400. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21288.

- Quarshie, E.-B., et al. Prevalence of self-harm among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents: A comparison of personal and social adversity with a heterosexual sample in Ghana. BMC Research Notes. 2020; vol. 13, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-020-05111-4.

- Meyer, I. H. Prejudice, social stress, and Mental Health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003; vol. 129, no. 5, pp. 674-697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

- Felner, J.K., Wisdom, J.P., Williams, T., Katuska, L., Haley, S.J., Jun, H., Corliss, H.L. Stress, coping, and context: Examining substance use among LGBTQ young adults with probable substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2019; 71:2, 112-120. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900029

- Dimova, E.D., Elliott, L., Frankis, J., Drabble, L., Wiencierz, S. and Emslie, C. Alcohol interventions for LGBTQ+ adults: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022; 41: 43-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13358

- Green, K. and Feinstein, B.A. Substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: An update on empirical research and implications for treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012; vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 265-278. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025424.

- Trocki, K., et al. Use of heavier drinking contexts among heterosexuals, homosexuals and bisexuals: Results from a national household probability survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005; vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 105-110. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2005.66.105.

- Pienaar, K., Murphy, D.A., Race, K., Lea, T. Drugs as technologies of the self: Enhancement and transformation in LGBTQ cultures. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2020; 78, 102673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102673

- Paschen-Wolff, M., et al. Simulating the experience of searching for LGBTQ-specific opioid use disorder treatment in the United States. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2022; vol. 140, p. 108828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108828.

- Giuntella, G, et al. Lifestyle and Mental Health Disruptions during COVID-19. SocArXiv Papers. 2020. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/y4xn3.

- Monaghesh, E., Alireza Hajizadeh. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: A systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020; vol. 20, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4.

- Nallapu, S, et al. A case series of substance abuse among urban slum population during the covid 19 pandemic. Industrial Psychiatry Journal. 2023; vol. 32, no. Suppl 1. https://doi.org/10.4103/ipj.ipj_241_23.

- Salerno, J. P., Doan, L., Sayer, L. C., Drotning, K. J., Rinderknecht, R. G., & Fish, J. N. Changes in mental health and well-being are associated with living arrangements with parents during COVID-19 among sexual minority young persons in the U.S. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2023; 10(1), 150-156. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000520

- Taylor, S., et al. Substance use and abuse, covid-19-related distress, and disregard for social distancing: A network analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2021; vol. 114, p. 106754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106754.

- Chacon, N., et al. Substance use during COVID-19 pandemic: Impact on the underserved communities. Discoveries. 2021; vol. 9, no. 4. https://doi.org/10.15190/d.2021.20.

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2015 (NSDUH-2015-DS0001). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Updated March 23, 2018. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2016 (NSDUH-2016-DS0001). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Updated March 23, 2018. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2017 (NSDUH-2017-DS0001). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Updated September 5, 2018. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2018 (NSDUH-2018-DS0001). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Updated August 26, 2019. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2019 (NSDUH-2019-DS0001). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Updated August 26, 2020. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2020 (NSDUH-2020-DS0001). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Updated October 28, 2021. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2021 (NSDUH-2021-DS0001). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Updated December 19, 2023. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

- Boyle, S.C., LaBrie, J.W., Omoto, A.M. Normative Substance Use Antecedents among Sexual Minorities: A Scoping Review and Synthesis. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2020; 7*(2), 117-131. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000373

- Feinstein, B.A., Mereish, E. H., Mamey, M.R., Chang, C.J., Goldback, J.T. Age Differences in the Associations Between Outness and Suicidality Archives of Suicide Research. 2023; 27*(2), 734-748. DOI: 10.1080/13811118.2022.2066493

- Tyndall, M. Safer opioid distribution in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2020; 83*, 102880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102880

- Alencar Albuquerque, G., de Lima Garcia, C., da Silva Quirino, G., Alves, M. J., Belém, J. M., dos Santos Figueiredo, F. W., da Silva Paiva, L., do Nascimento, V. B., da Silva Maciel, É., Valenti, V. E., de Abreu, L. C., & Adami, F. Access to health services by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: systematic literature review. BMC international health and human rights. 2016; 16(2). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0072-9

- Capasso, A., Jones, A. M., Ali, S. H., Foreman, J., Tozan, Y., & DiClemente, R. J. Increased alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic: The effect of mental health and age in a cross-sectional sample of social media users in the U.S. Preventive medicine. 2021; 145, 106422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106422

- Lyden, J., Binswanger, I.A. The United States opioid epidemic. Seminars in Perinatology. 2019; 43*(3), 123-131. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2019.01.001