Surgical Technique for Knee Arthroplasty Bone Defects

Description of a Surgical Technique for the Treatment of Bone Defects in Knee Arthroplasties: Modified Stonehenge

João Gabriel de Campos Villardi1, Caio Lima de Mello1, Leonardo Calazans Machado1, Matheus Wehremann Luzzardi2, Rafael Erthal Cruz3, Tiago Carminatti4, Alfredo Marques Villardi5

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 November 2024

CITATION: Villardí, JGDCC., Mello, CLD., et al., 2024. Description of a Surgical Technique for the Treatment of Bone Defects in Knee Arthroplasties: Modified Stonehenge. Medical Research Archives, [online] 12(11).

https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i11.6030

COPYRIGHT :© 2024 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i11.6030

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Bone loss can be a major problem in knee arthroplasties. Although bone defects are more common in revision arthroplasties, due to loosening, infection and removal of material, they can also occur in primary arthroplasties, due to some factors, such as inflammatory arthropathies, long waiting times for surgery, sequelae of fractures or infection, among others. There are several classifications described in the literature that can be useful, not only for planning bone loss in arthroplasties, but also to serve as a treatment guide. The AORI classification is one of the most used and it is the one we prefer because it has good reproducibility and it gives a good idea of how to fill defects and the necessary bone stock. Lombardi’s classification, in addition to defining the depth of the defect, considers the defect’s dependence on the integrity of the bone. This report describes the technique of Modified Stonehenge, which is used to fill bone defects in knee arthroplasties.

Keywords: knee arthroplasties, bone defects, Modified Stonehenge technique

Introduction

Bone loss can be a major problem in knee arthroplasties. Although bone defects are more common in revision arthroplasties, due to loosening, infection and removal of material, they can also occur in primary arthroplasties, due to some factors, such as inflammatory arthropathies, long waiting times for surgery, sequelae of fractures or infection, among others. There are several classifications described in the literature that can be useful, not only for planning bone loss in arthroplasties, but also to serve as a treatment guide. The AORI classification is one of the most used and it is the one we prefer because it has good reproducibility and it gives a good idea of how to fill defects and the necessary bone stock. Lombardi’s classification, in addition to defining the depth of the defect, considers the defect’s dependence on the integrity of the bone.

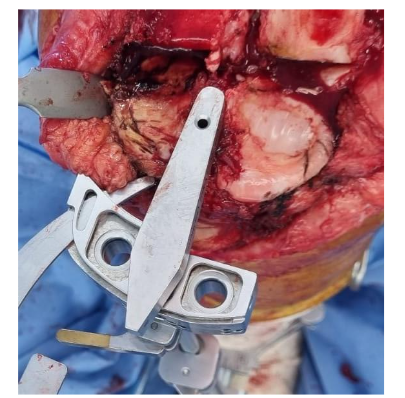

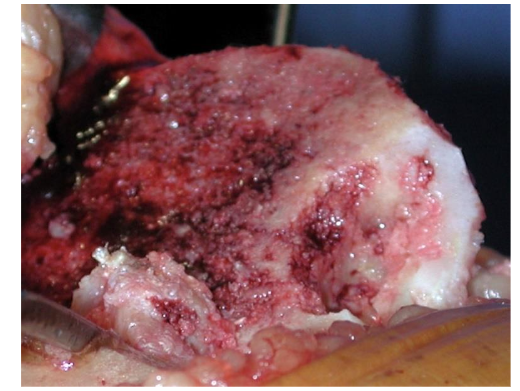

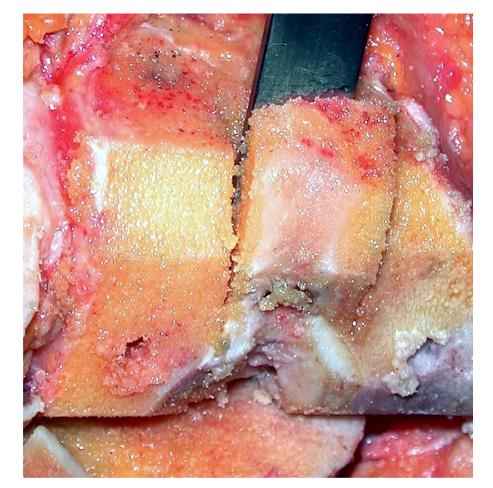

We begin the Modified Stonehenge technique by evaluating the magnitude of the defect and its containment characteristics (Figures 2 and 3), evaluating the magnitude of the defect and its containment characteristics.

Preparing the Bone Defect

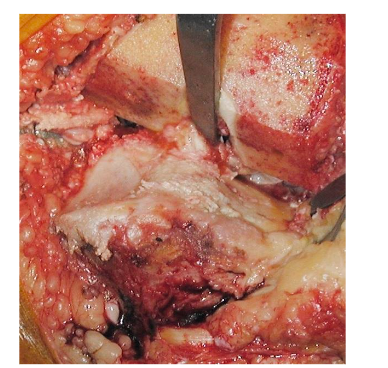

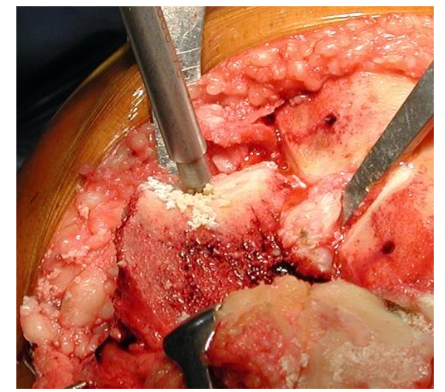

Bone defect 10 mm deep is removed in the defect area, removing as much of the sclerotic bone as possible and obtaining a more vascularized and uniform defect floor for graft impaction, thereby avoiding dead space between the graft and the corresponding recipient area. Drilling can be carried out with the drills available for the medullary canal or patellar pegs. (Fig.4)

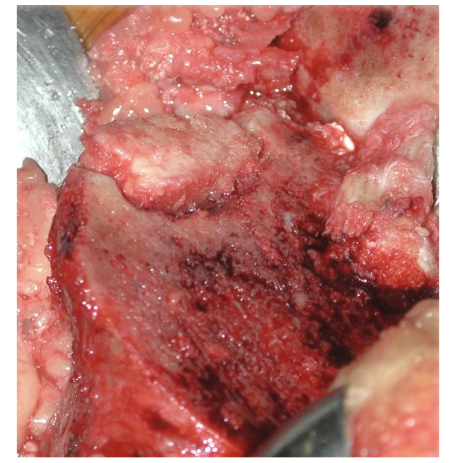

Residual bone bridges formed must be removed with gouges, osteotomes or very sharp burs, which provide a better finish to the recipient area. (Fig.5)

Preparing the Graft

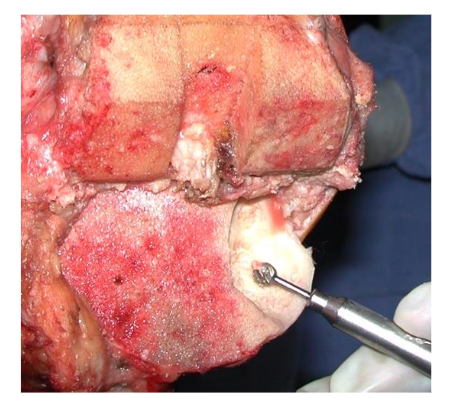

The graft to be used can be obtained from preserved bone from any bone cut. However, the fragments should come from the cut of the posterior stabilization box and from the femoral chambers as the most frequently used. (Fig.7)

The width of the graft must be 1 to 2 mm greater than the defect it is press-fit, so that the filling of the defect is ensured. (Fig.9)

Preferably, a polyethylene implant available in different arthroplasty systems is used, or even a wide osteotome, in a horizontal position, on which the graft will be impacted until it is level with the bone surface. (Fig.11)

If, even after impaction, the graft remains to be shaped, an oscillating saw must be used to level the graft. (Fig.12)

Graft flush with the cut surfaces. Source: Author’s personal archive

Graft flush with the cut surfaces. Source: Author’s personal archive

Figure 9: Graft positioned 1 to 2 mm wider than the defect.

Source: Authors’ personal archive

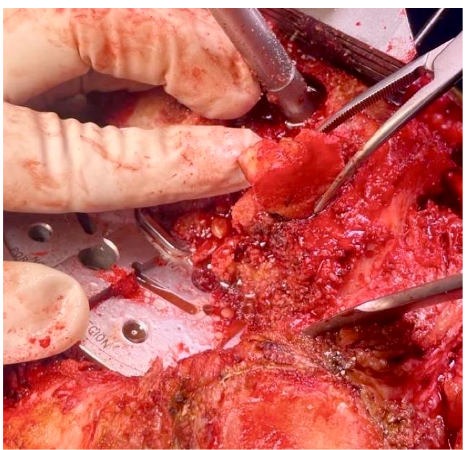

Impaction and Regularization of the Graft

The graft shaped is placed and then, must be impacted under pressure, using an impactor wider than the graft to avoid its fracture. (Fig. 10)

Figure 10: Placement of the shaped graft on the lateral femoral condyle in revision arthroplasty.

Source: Authors’ personal archive

Preferably, a polyethylene impactor available in different arthroplasty systems is used, or even a wide osteotome, in a horizontal position, on which the graft will be impacted until it is level with the bone surface. (Fig. 11)

Figure 11: Impacted graft in the lateral femoral condyle.

Source: Authors’ personal archive

If, even after impaction, the graft remains above the bone surface, an oscillating saw must be used to level the graft. (Fig. 12)

Figure 12: Graft levelled using the oscillating saw.

Source: Authors’ personal archive

If there is still a gap in the recipient area, small fragments of cancellous bone must be impacted until the defect is completely covered. (Fig. 13)

Figure 13: Graft flush with the cut surface. The space between the tibial plateau and the graft must be filled with impacted bone fragments. The appearance of the graft resembles the structure of Stonehenge.

Source: Authors’ personal archiveOnce the proximal tibial bone cut is flush, using the Modified Stonehenge technique, the preparation of the tibial component bed must be carried out in the conventional way, with drilling for the stem and preparation for the delta of the definitive component, with no risk of fracture of the graft or loss of the positioning obtained. Cementation of the definitive component is also performed conventionally, with no need to modify the standardized technique, due to grafting.

Discussion

The technique described (Modified Stonehenge) allows the correction of bone defects whether contained or not, using autologous grafting, with bone fragments resulting from bone cuts, which can be used in both the femur and tibia. As advantages, we highlight the small increase in surgical time, which is around 10 minutes. The technique does not require any specific instruments.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References

- Engh, G. A.; Parks, N. L. The management of bone loss in revision TKA: it’s a changing world. Orthopedics, 33-39, 2010.

- Pecora, J. R. et al.; Intersobserver correlation in classification of bone loss in total knee arthroplasty. Acta Ortopédica Brasileira, v. 19, 368-372, 2011.

- Lombardi Jr, Adolph V., Keith R. B., Joanne B. A. Management of bone loss in revision TKA: it’s a changing world. Orthopedics, 33-39, 2010.

- Kelbish, P.A.; Prosthetic fixation in cementless total knee arthroplasty. Biomecânica, 2, 46-50, 2011.