Telehealth Training for Nursing Students Using AI Simulations

Evaluation of ChatGPT artificial intelligence dialogues and simulated scenarios to prepare nursing students for telehealth practicum

Lorena D. Paul, DNP, MEd, GCNE, RN-BC1

Associate Professor, School of Nursing and Health Professions, University of the Incarnate Word, San Antonio, Texas 78209, USA

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 July 2025

CITATION:Paul, LD., 2025. Evaluation of ChatGPT artificial intelligence dialogues and simulated scenarios to prepare nursing students for telehealth practicum. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(7). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6786

COPYRIGHT:© 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6786

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Background: Telehealth care technologies and innovations will continue to expand and provide the means for improving quality and access to health care services. Respectively, the professional, research, academic, and leadership responsibilities include informing, educating, and resourcing future generations of health care providers for telehealth practices. Thus, an academic-practice partnership consisting of nursing faculty and Federally Qualified Health Center registered nurses co-facilitated a primary care telehealth practicum to prepare baccalaureate nursing students for practice. When the students expressed lack of confidence in conducting telephone calls with the patients, the faculty piloted a telehealth orientation that included simulated ChatGPT dialogues and virtual scenarios with motivational interviewing feedback.

Aim: The purpose of the pilot project was to evaluate the combined effectiveness of artificial intelligence and virtual simulation scenarios in terms of increasing 32 senior level students’ perceived readiness and participation during telehealth practicums with faculty, primary care nurses, and enrolled patients.

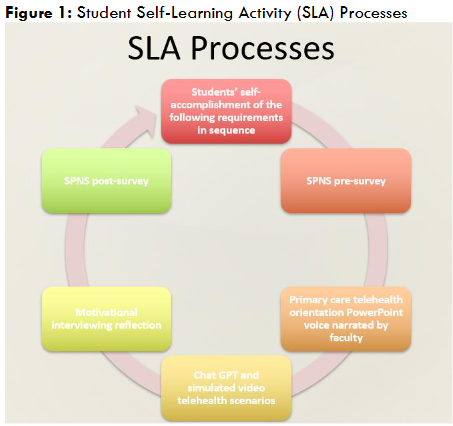

Methods: The Plan, Do, Study, Act framework was applied to develop, implement, and evaluate the pilot telehealth orientation. The project processes included students’ accomplishments of the following: pre-survey, simulated ChatGPT and virtual learning activities, reflection, and post-survey. The Special Projects of National Significance Program Cooperative Agreement Evaluation survey was applied to measure the students’ perceived abilities to counsel and manage clients. A combination of qualitative and quantitative methods was used to evaluate the students’ perceived gains related to telehealth facilitation skills, attitudes, and comfort. With consideration for the small sample size and non-normal data distribution, the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test was applied to determine the significance of students’ perceived skills, attitudes, and comfort gains.

Results: Following completion of the telehealth orientation and simulations, the students’ perceived significant increases in abilities to counsel and manage clients’ when providing telehealth services and overall knowledge of telehealth applications within the context of primary care.

Conclusions: Combined simulation and live telehealth learning activities during prelicensure programs may be used to prepare future health care providers for practice in the Digital Era, and to measurably demonstrate value to the health care team and system by decreasing health care costs and increasing clients’ access to services.

Keywords

telehealth, nursing education, artificial intelligence, ChatGPT, simulation, nursing students

Introduction

CONTEXT

Fast-forwarding into the Digital Era, telehealth care innovations will continue to expand across the health care continuum, support the health care needs of communities in both near and distant locations, and address social determinants of health. Benefits and opportunities relate to the variety and convenience of provider/patient communication modalities and efficiencies related to health care access, time, and cost. Challenges include but are not limited to preserving clients’ confidentiality and overcoming social health disparities such as poverty, illiteracy, and lack of access to technologies.

Respectively, the professional, research, academic, and leadership responsibilities pertain to informing, educating, and resourcing the current and future generations of telehealth care providers. Additionally, telehealth services should be designed and aligned with consideration for strategic health care system priorities including timeliness, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, efficiency, equity, and safety.

APPLICATIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING PRACTICE

Practicing nurses provide telehealth services in a variety of settings across the health care continuum in support of value-based health care priorities which include cost control and optimal client health outcomes. Telehealth nursing roles often focus on triage, remote patient monitoring and the facilitations of client care access, management, coordination, and transition. Within the nursing profession, there are established practice guidelines and a growing body of evidence related to telehealth. The American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing has published standards for professional telehealth nursing and a conceptual framework both of which are based on the nursing process.

The nursing process metatheory includes assessment, nursing diagnoses, outcomes identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation and is traditionally applied regardless of the nursing care context (i.e., in-person or telehealth). Opportunities exist for pre-licensure programs to incorporate telehealth experiences in undergraduate curricula and simulated telehealth learning activities have provided an effective means for preparing the future nursing workforce to be competent and supportive of the interprofessional health care team’s efforts.

Recent literature and research focused on the evaluation of faculty-facilitated interactions between standardized patients and students for various purposes such as advancing client interaction skills during the COVID pandemic; expanding the quantity of clinical experiences in response to increased student enrollments; and preparing students for licensed practice within the changing health care environment. Simulation facilitation challenges related to shortages of qualified nursing faculty facilitators, technical glitches and equipment difficulties, and students’ discomfort. Research limitations included inability to generalize findings due to small sample sizes, limited location and clinical contexts, short term focus, and convenience samples, as well as students’ biases, lack of data collection, limited focus on students’ attitudes, and faculty developed evaluation surveys.

Controversies focused on the lack of telehealth training and intervention studies in undergraduate programs and the urgent need to prepare students for digital health care paradigm shifts. Simulation design and implementation differences related to the application of International Nursing Association of Clinical Simulation and Learning (INACSL) standards intended to promote academic and research excellence. Artificial intelligence (AI) is currently being applied by nurse educators for various purposes such as supporting the accomplishment of student learning outcomes, organizing instructional processes, and refining patient care training. Research gaps related to the combination of nursing student self-learning activities and AI to prepare undergraduate students for telehealth practicums with live clients and/or licensed practice.

With consideration for the current literature review findings, the purpose and scope of this paper are to evaluate senior-level baccalaureate nursing students’ perceived telehealth competencies following self-accomplishment of interactive computer-based video simulations and ChatGPT conversations in preparation for a telehealth clinical practicum with live clients assisted by faculty and primary care nurses.

CLINICAL PROBLEM STATEMENT

During multiple 4-hour telehealth practicums facilitated by faculty and primary care nurses, senior level nursing students expressed anxiousness about conducting visits with live patients by telephone without visual cues. Their lack of self-confidence delayed the initiation and progression of the practicums. Additionally, several individuals from each clinical group did not have an opportunity to accomplish the telehealth clinical objectives related to triaging, assessing, and addressing a client’s acute primary care needs. Using Mueck’s four-factor framework the problem was stated as follows: Risk of inabilities to accomplish telehealth practicum objectives; among senior level nursing students without prior telephonic experiences with live clients; due to reluctance to participate during the clinical practicum; as evidenced by perceived inabilities within cognitive, affective, and behavioral domains. To address this problem, the faculty piloted an academic quality improvement project using no-cost, readily available resources including a virtual voice-narrated orientation, interactive computer-based video simulations, and ChatGPT conversational AI chatbot.

PURPOSE STATEMENT AND NULL HYPOTHESIS

The aim was to increase the students’ perceived cognitive, affective, and behavioral telehealth facilitation competencies prior to participating in practicums with live clients facilitated by faculty and primary care nurses. The corresponding hypothesis was stated as follows: Nursing students will report no significant differences in perceived cognitive, affective, and behavioral telehealth skills after completing a self-directed learning activity that includes telehealth orientation and accomplishments of four simulated assignments.

Methods

PILOT PROJECT DESIGN

A pre- and post-survey design was applied to evaluate senior level baccalaureate nursing students’ perceived readiness for a live telehealth clinical practicum after completing a self-learning activity. This included four simulated telehealth self-learning assignments powered by an AI chatbot and a commercially developed product that generated motivational interviewing feedback. A combination of quantitative and qualitative methods was utilized to obtain a broader understanding of the students’ perceived gains related to telehealth facilitation skills, attitudes, and comfort. The Wilcoxon signed-ranks test was applied to compare the significance of the students’ pre and post survey results. Faculty also reviewed the students’ self-learning activity completion times and their motivational interviewing performance feedback reports that were generated by the commercial product.

SETTING AND SAMPLE

The telehealth pilot project was conducted between January and May of 2025 by nursing faculty at a private university that is centrally located within a metropolitan city of the United States. A convenience sample was comprised of first-degree, senior level nursing students enrolled in the community health nursing course during the final semester of the traditional in-person baccalaureate nursing program (n=32). All students who were enrolled in the course were invited to participate. Exclusion criteria included incomplete or late submission of the self-learning activity’s assignments and/or student absence during the telehealth clinical practicum. Males comprised 9% (3/32) of the sample.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The university’s Institutional Review Board classified the telehealth pilot project as non-regulated research. The students’ clinical assignments were secured within the didactic course learning management system in compliance with the United States Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

INSTRUMENT

The Special Projects of National Significance (SPNS) Program Cooperative Agreement Evaluation Module 57: Training Evaluation Form Skills Attitudes Comfort National Evaluation pre- and post-survey was applied to evaluate the students’ perceived cognitive, behavioral, and affective gains related to telehealth encounter facilitation with permission granted for non-commercial use. The SPNS survey contained four items rated on a Likert-type scale of 1 to 5 including the overall knowledge of topics covered prior to and after the training, perceived abilities to counsel and manage clients, and comfort level in providing services. Corresponding nominal categories were incorporated into the survey. These included “low” (1-2), “medium” (3), and “high” (5-6).

PROCEDURES

The Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) framework guided the pilot project preparations, implementation, and evaluation. The Plan phase occurred prior to the Spring 2025 semester and included the development of the telehealth lesson plan, the students’ self-learning activity (SLA) instructions and prompts, the SLA assignment grading rubric, and the telehealth practicum rotation schedule for each clinical group. The Do phase aligned with the clinical schedule which began three weeks into the Spring 2025 semester. Two weeks prior to attending the telehealth clinical practicum with live clients, faculty, and primary care nurses, the students were given four clinical hours to complete the SLA that included pre and post readiness surveys. The Study phase also aligned with the clinical schedule. The faculty assessed the students’ perceived readiness to participate during the upcoming telehealth practicum by comparing their pre and post survey results. The Act phase aligned with the telehealth clinical practicum dates during which faculty observed and evaluated the students for their accomplishments of the clinical objectives that were mapped to essential nursing competencies.

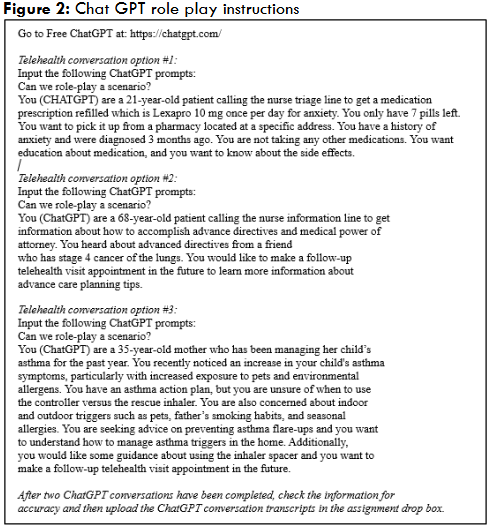

The SLA contained eight assignments to be completed in the following sequence: the SPNS pre-survey, a 15-minute voice-narrated telehealth orientation developed by the faculty; two commercially prepared telehealth simulation scenarios that provided motivational interviewing (MI) feedback; two student-facilitated role-play transcripts with ChatGPT designated as the client; a MI reflection, and the SPNS post-survey.

The voice-narrated telehealth orientation topics included definitions of telehealth, originating site, and distance site; common types of telehealth care such as video visits, remote patient monitoring, surveillance, e-mails through secure patient portals, telephonic, and text messaging; history and evolution of telehealth care; common applications within various institutional and community based settings; MI; professional etiquette and presence; patient teaching tips; employment, training, and certification opportunities; recommended framework for conducting primary care telephonic episodes of care; and evidence-informed references.

The two commercially prepared telehealth simulations were accessed by students through a secure learning management system. Both simulations facilitated applications of MI techniques during follow-up telehealth episodes of care with patients who were experiencing problems with chronic disease management. After they completed the simulated video telehealth scenarios, the students were provided with a MI performance feedback report which they used to inform and document a clinical reflection.

The ChatGPT role play instructions included navigation aids and prompts for completing and documenting a minimum of two telehealth conversations. Students were given the choice to either create their own scenarios or select two of three scenarios created by faculty.

DATA ANALYSIS

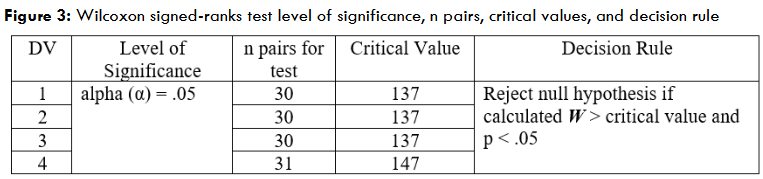

The Wilcoxon signed-ranks test was applied to compare the median results of SPNS pre and post survey measurements on the same subjects with the following assumptions: interval-level variables; results not normally distributed; and small sample size with at least five matched pairs. The dependent variables (DV) included the students’ perceived abilities to counsel clients, perceived abilities to manage clients, comfort providing services, and overall knowledge. For each of the matched pairs, the level of significance was set at alpha = .05.

Additionally, the faculty conducted a qualitative analysis of the students’ motivational interviewing feedback to identify their specific communication strengths and opportunities prior to attending the clinical practicum with live clients. The secure learning management system also provided information of interest such as the average amount of time for students to complete the simulations and their performance critiques.

Results

QUANTITATIVE

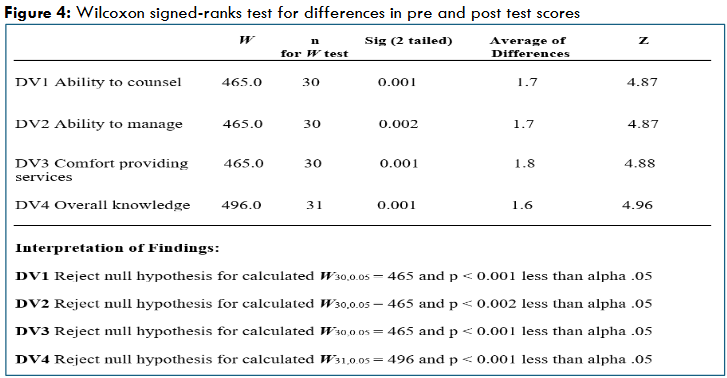

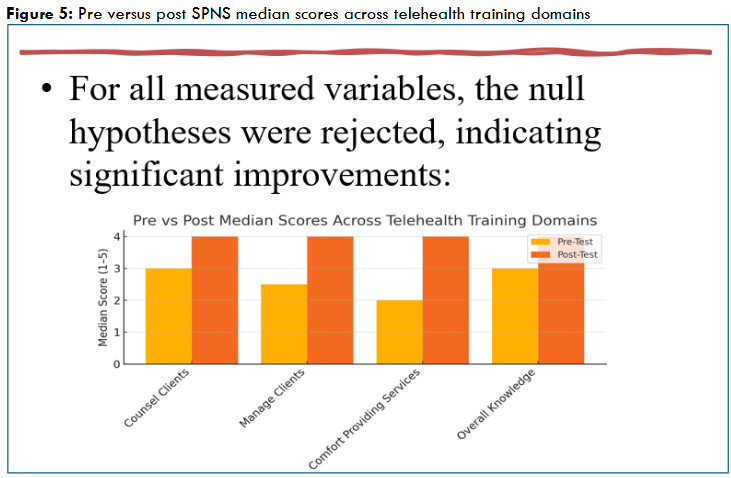

After completing the telehealth orientation and simulations, the students’ perceived significant increases in abilities to counsel and manage clients, comfort level in providing telehealth services, and overall knowledge of telehealth applications within the context of primary care as evidenced by the following: DV1 ability to counsel clients about the topic(s) covered in this training (p< .001) with estimated median pre-test score = 3 (range = 1-5) and estimated median post-test score = 4 (range = 3-5), Z = 4.87; DV2 ability to manage clients regarding topic(s) covered in this training (p<.002) with estimated median pre-test score = 2.5 (range = 1-5) and estimated median post-test score = 4 (range = 3-5), Z = 4.87; DV3 comfort level in providing services to clients in relation to the topic(s) covered in this training (p< .001) with estimated median pre-test score = 2 (range = 1-5) and estimated median post-test score = 4 (range = 3-5), Z = 4.88; DV4 overall knowledge of the topic(s) covered in this training (p< .001) with estimated median pre-test score = 3 (range = 1-5) and estimated median post-test score = 4 (range = 3-5), Z = 4.96.

QUALITATIVE

Out of the total of 32 students, 28 (87.5%) shared their motivational interviewing feedback from the two commercially prepared simulations with the faculty. The average time spent was 1 hour, 52 minutes, ranging from 57 minutes to 6 hours, 50 minutes. After completing the simulations, the students received one of two possible feedback messages. Either they successfully motivated the client to follow through with the chronic disease self-care plan (feedback one), or they missed one or more opportunities to motivate the client (feedback two). Out of the sub-total of 28 students, 7 (25%) received feedback one for both simulated clients; 12 (42.8%) received feedback one for one simulated client; and 9 (32%) received feedback two for both simulated clients.

Discussion

DECISION RULE APPLIED TO CHANGES IN SURVEY MEDIAN SCORES

The priority research question focused on students’ perceived confidence and competence related to the following dependent variables: counseling clients, managing client care, providing nursing services, and knowledge of facilitating telehealth episodes of care. With consideration for changes in pre and post median survey scores, the null hypotheses were rejected for all dependent variables, indicating significant improvements for all four measured clinical competencies. The median pre-survey scores ranged from 2.0 to 3.0 and the median post-survey scores increased to 4.0 across all variables, suggesting that the combination of a telehealth orientation, AI powered conversations, and commercially prepared simulated self-learning activities enhanced the students’ perceived abilities.

STUDENTS’ PERCEIVED SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE GAINS

Telehealth competency indicators of interest related to the following nursing functions: client education, care management, clinical judgment, facilitation, and collaboration.

- Counseling clients (DV1): 44% of the students selected “low” ability on the pre-survey; 100% self-rated “high” on the post-survey. A probable mediating factor was the pre-nursing education program’s concept-based curriculum that integrates communication and patient education concepts and exemplars during all courses. The concept-based approach to nursing education is a contemporary learning method that emphasizes broad concepts applied in various clinical contexts rather than the remembrance of isolated facts. The aim of concept-based curricula is to promote and expedite the learners’ adaptability to continuously changing clinical contexts across the health care continuum. Theoretically, students may initially feel uncomfortable when introduced to or immersed in a new clinical environment such as primary care telehealth, but they will quickly become confident in their abilities to accomplish the clinical objectives when they realize that they are applying transferable concepts and competencies. Catalysts of the transference process such as AI-powered role plays can be applied and customized by faculty according to the clinical context, although subject matter experts currently recommend standardized patients and simulation protocols rather than role-play to optimize learning outcomes.

- Managing clients (DV2): 51% of the students stated “low” ability on the pre-survey; 100% reported “high” on the post-survey. Probable mediating factors included the students’ participations in primary care simulations during earlier courses in the curriculum that were supported by virtual reality (VR) and high-fidelity mannequins (HFM) technologies. The VR and HFM simulation methods offer a realistic, safe, and less stressful learning environment for students to practice emergency responses to high-risk, problem-prone, and/or low-volume clients who may not be encountered during the planned clinical rotations including primary care. Although AI-powered role plays may be less stimulating, they may also be more realistic than the VR and HFM simulations that permit the students’ visibility of patients’ non-verbal cues such as eye contact and facial expressions.

- Comfort providing telehealth services (DV3): 54% of the students chose “low” comfort on the pre-survey; 100% specified “high” on the post-survey. Probable mediating factors related to students’ prior applications of the clinical judgment model during each didactic class and clinical practicum of the program. The clinical judgment model aligns with the nursing process meta-theory which includes assessment, problem/needs identification, care planning, implementation, and evaluation and is applied in all nursing care contexts. Combining the clinical judgment model with other theoretical frameworks such as social determinants of health (SDOH) is a best practice for advancing students’ multi-dimensional cognition and skills and for facilitating new clinical experiences such as primary care telehealth. For example, clinical faculty may integrate the SDOH model and motivational interviewing principles during AI-powered role plays to facilitate the students’ broader understanding of extrinsic and intrinsic client factors that impact their health outcomes and inform the application of the nursing process.

- Overall knowledge (DV4): 35% of the students perceived “low” knowledge on the pre-survey; 100% affirmed “high” on the post-survey. A known mediating factor was the nursing students’ prior participation in a simulated interprofessional primary care video conference with a standardized patient and students from the medicine, pharmacy, nutrition, and physical therapy programs. The primary care simulation was designed by an interprofessional team of faculty with consideration for the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) core competencies and framework that standardize the development, implementation, and evaluation of collaborative learning activities. Faculty facilitation of interprofessional learning activities develops students’ collective identity and advances their professional socialization which are foundational for collaborative patient care in the future. Opportunities exist to pilot interprofessional AI-powered primary care telehealth role play scenarios that exclude the students’ visibility of patients’ non-verbal cues in accordance with clinical practice realities.

STATUS OF PILOT PROJECT PROBLEM RESOLUTION

In follow up to the original problem statement, all nursing students who completed the telehealth orientation and the four simulation activities also successfully accomplished their clinical objectives related to triaging, assessing, and addressing one patient’s acute care needs as evidenced by the successful facilitation of one live episode of care assisted by the faculty and primary care nurses.

ACADEMIC IMPLICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS

During PDSA cycle 1, the students’ most significant gains related to managing client care and providing telehealth services within the primary care clinical context. PDSA cycle 2 will focus on the development, implementation, and evaluation of two AI powered standardized patients that will support telehealth simulation scenarios within multiple clinical contexts across the health care continuum for the purposes of increasing students’ perceived confidence and competence related to facilitating health care transitions and continuity.

PILOT PROJECT STRENGTH AND LIMITATIONS

Although PDSA cycle 1 appeared to successfully address the immediate clinical practicum needs, it cannot be assumed that the desired outcomes will occur again during the future semesters. Additional pilot project limitations included use of a generalized pre/post survey instrument; small convenience sample; limited location and clinical contexts; lack of pilot project protocol rigor (i.e., students’ biases and choice to create their own ChatGPT scenarios); students’ recall of prior academic experiences; known, probable, and unknown academic variables; limited and short-term focus; and the non-generalizability of findings to other telehealth clinical practicum contexts.

Conclusion

Telehealth is currently being facilitated by registered nurses and other health care providers within a variety of clinical settings to increase patients’ access to quality care across the health care continuum. Career-enhancing telehealth opportunities are projected to expand during the Digital Era and future nurses need to be prepared to participate and measurably demonstrate their value to the health care team in terms of decreasing health care costs and improving clinical outcomes. Our pilot project findings suggested that the combined use of AI and commercially prepared role play simulations may offer a viable means to prepare nursing students for clinical practicums with live clients and licensed practice in the digital era.

RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES

Currently, there is limited evidence to support faculty facilitation of telehealth practicums in undergraduate nursing programs. Recent studies concentrated on the effectiveness of simulated telehealth scenarios with standardized patients in various health care contexts. Future opportunities include but are not limited to evaluating the impacts of applying AI powered role plays, standardized patients, and simulations to prepare students for licensed practice across the health care spectrum.

Conflicts of Interest Statement:

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgement:

The author thanks Dr. Sarah H. Ailey for telehealth mentorship.

References

- Isidori V, Diamanti F, Gios L, et al. Digital technologies and the role of health care professionals: scoping review exploring nurses’ skills in the digital era and in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. JMIR Nurs. 2022;5(1):e37631. doi:10.2196/37631

- Ezeamii VC, Okobi OE, Wambai-Sani H, et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: how telemedicine is improving patient outcomes and expanding access to care. Cureus. 2024;16(7):1-10. doi:10.7759/cureus.63881

- Roy J, Levy DR, Senathirajah Y. Defining telehealth for research, implementation, and equity. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(4):e35037. doi:10.2196/35037

- Sheperis DS, Smith A. Telehealth best practice: a call for standards of care. J Technol Couns Educ Superv. 2021;1(1):27-35. doi:10.22371/tces/0004

- Dinesen B, Nonnecke B, Lindeman D, et al. Personalized telehealth in the future: a global research agenda. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(3):e53. doi:10.2196/jmir.5257.

- Rising KL, Kemp M, Leader AE, et al. A prioritized patient-centered research agenda to reduce disparities in telehealth uptake: results from a national consensus conference. Telemed Rep. 2023;4(1):387-395. doi:10.1089/tmr.2023.0051

- Chike-Harris KE, Durham C, Logan A, Smith G, DuBose-Morris R. Integration of telehealth education into the health care provider curriculum: a review. Telemed e-Health. 2021;27(2):137-149. doi:10.1089/tmj.2019.0261

- Jonasdottir SK, Thordardottir I, Jonsdottir T. Health professionals’ perspective towards challenges and opportunities of telehealth service provision: a scoping review. Int J Med Inform. 2022;167:104862. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104862

- Rangachari PA. Holistic framework of strategies and best practices for telehealth service design and implementation. In: Pfannstiel MA, Brehmer N, Rasche C, eds. Service Design Practices for Healthcare Innovation. Springer International Publishing; 2022:315-335.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity. National Academy of Medicine; 2021. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/25982/the-future-of-nursing-2020-2030-charting-a-path-to

- American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing. Scope and Standards of Practice for Professional Telehealth Nursing. 6th ed. American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing; 2018.

- Rambur B, Palumbo MV, Nurkanovic M. Prevalence of telehealth in nursing: implications for regulation and education in the era of value-based care. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2019;20(2):64-73. doi:10.1177/1527154419836752

- Alharbi AA, Almalki MHM, Alhawit ME, et al. The impact of value-based care models: the role of nurses and administrators in healthcare improvement. Int J Health Sci. 2022;6(S10):2186-2211. doi:10.53730/ijhs.v6nS10.15411

- Bartz CC. Telehealth nursing research: adding to the evidence-base for healthcare. J Int Soc Telemed eHealth. 2020;8(e19):1-9. doi:10.29086/JISfTeH.8.e19

- Ali-Saleh O, Massalha L, Halperin O. Evaluation of a simulation program for providing telenursing training to nursing students: cohort study. JMIR Med Educ. 2025;11:e67804. doi:10.2196/67804

- Bdair IA. Perceptions of pre-licensure nursing students toward telecare and telenursing. Inform Health Soc Care. 2024;49(1):42-55. doi:10.1080/17538157.2022.2162140

- Gutiérrez-Puertas L, Gutiérrez-Puertas V, Ortiz-Rodríguez B, Márquez-Hernández VV, Granados-Gámez G. Communication and empathy of nursing students in patient care through telenursing: a comparative cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2024;126:105834. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2023.105834

- Mun M, Choi S, Woo K. Investigating perceptions and attitude toward telenursing among undergraduate nursing students for the future of nursing education: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):236. doi:10.1186/s12912-024-01903-2

- Rossler KL, Badowski D, Siegel S. The presence of simulated telehealth in prelicensure nursing education: a scoping review. Clin Simul Nurs. 2023;77:15-22. doi:10.1016/j.ecns.2023.05.003

- Thomas RM, Moore LP, Urquhart BB, et al. Use of simulated telenursing with standardized patients to enhance prelicensure nursing education. Nurse Educ. 2023;48(6):E191-E195. doi:10.1097/NNE.0000000000001410

- Simmons S, Tabi M, Bester E, Zanetos J. Integrating telehealth into nursing education through standardized patient simulation. Clin Simul Nurs. 2024;97:101647. doi:10.1016/j.ecns.2024.101647

- Moore J, Jairath N, Montejo L, O’Brien S, Want D. Using a telehealth simulation to prepare nursing students for intraprofessional collaboration. Clin Simul Nurs. 2023;78:1-6. doi:10.1016/j.ecns.2023.02.007

- DeFoor M, Darby W, Pierce V. “Get Connected”: Integrating telehealth triage in a prelicensure clinical simulation. J Nurs Educ. 2020;59(9):518-521. doi:10.3928/01484834-20200817-12

- Posey L, Pintz C, Zhou QP, Lewis K, Slaven-Lee P. Nurse practitioner student perceptions of face-to-face and telehealth standardized patient simulations. J Nurs Regul. 2020;10(4):37-44. doi:10.1016/S2155-8256(20)30012-0

- Watkins SM, Jarvill M, Wright V. Simulated telenursing encounters with standardized participant feedback for prelicensure nursing students. Nurse Educ. 2022;47(2):125-126. doi:10.1097/NNE.0000000000001100

- Greenberg ME, Rutenberg C. Telehealth and virtual care nursing. In: Coburn CV, Gilland D, Swan BA, eds. Perspectives in Ambulatory Care Nursing. Wolters Kluwer; 2022:163-183.

- Durnas H. Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best PracticeTM. www.inacsl.org. Published 2021. Accessed May 31, 2025. https://www.inacsl.org/healthcare-simulation-standards-ql

- Shorey S, Ang E, Yap J, Ng ED, Lau ST, Chui CK. A virtual counseling application using artificial intelligence for communication skills training in nursing education: development study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(10):e14658. doi:10.2196/14658

- Buchanan C, Howitt L, Wilson R, Booth RG, Risling T, Bamford M. Predicted influences of artificial intelligence on nursing education: scoping review. JMIR Nurs. 2021;4(1):e23933. doi:10.2196/23933

- Castonguay A, Farthing P, Davies S, et al. Revolutionizing nursing education through AI integration: a reflection on the disruptive impact of ChatGPT. Nurse Educ Today. 2023;129:1-3. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2023.105916

- DeGagne JC. The state of artificial intelligence in nursing education: past, present, and future directions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(6):4884. doi:10.3390/ijerph20064884

- Glauberman G, Ito-Fujita A, Katz S, Callahan J. Artificial intelligence in nursing education: opportunities and challenges. Hawaii J Health Soc Welfare. 2023;82(12):302-305. Accessed May 31, 2025. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10713739/pdf/hjhsw8212_0302.pdf

- Bumbach MD, Carrington JM, Love R, Bjarnadottir R, Cho H, Keenan G. The use of artificial intelligence for graduate nursing education: an educational evaluation. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2024;36(9):486-490. doi:10.1097/JXX.0000000000001059

- Muecke MA. Community health diagnosis in nursing. Public Health Nurs.1984;1(1):23-35. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1446.1984.tb00427.x

- U.S. Department of Education. FERPA: Protecting student privacy. studentprivacy.ed.gov. Updated December 2, 2011. Accessed May 31, 2025. https://studentprivacy.ed.gov/ferpa

- SPNS Program Cooperative Agreement Evaluation Module 57: Training Evaluation Form: Skills, Attitudes, Comfort. Go2itech.org. March 22, 1996. Accessed May 31, 2025. https://www.go2itech.org/HTML/TT06/toolkit/evaluation/forms.html

- Plichta SB, Kelvin EA. Munro’s Statistical Methods for Health Care Research. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- Al-Omari E, Dorri R, Blanco M, Al-Hassan M. Innovative curriculum development: embracing the concept-based approach in nursing education. Teaching and Learning in Nurs. 2024;19(4):324-333. doi:10.1016/j.teln.2024.04.018

- Repsha CL, Quinn BL, Peters AB. Implementing a concept-based nursing curriculum: a review of the literature. Teaching and Learning in Nurs. 2020;15(1):66-71. doi:10.1016/j.teln.2019.09.006

- Cortés-Rodríguez AE, Roman P, López-Rodríguez MM, Fernández-Medina IM, Fernández-Sola C, Hernández-Padilla JM. Role-play versus standardised patient simulation for teaching interprofessional communication in care of the elderly for nursing students. Healthcare. 2022; 10(1):46. doi:10.3390/healthcare10010046

- Jiang N, Zhang Y, Liang S, et al. Effectiveness of virtual simulations versus mannequins and real persons in medical and nursing education: meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e56195-e56195. doi:10.2196/56195

- Magi CE, Bambi S, Iovino P, et al. Virtual reality and augmented reality training in disaster medicine courses for students in nursing: a scoping review of adoptable tools. Behav Sci. 2023;13(7):616. doi:10.3390/bs13070616

- Clinical judgment measurement model. NCLEX.org. January 22, 2019. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.nclex.com/clinical-judgment-measurement-model.page

- Jessee MA. An update on clinical judgment in nursing and implications for education, practice, and regulation. J Nurs Regul. 2021;12(3):50-60. doi:10.1016/s2155-8256(21)00116-2

- IPEC core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: version 3. ipecollaborative.org. November 20, 2023. Accessed July 11, 2025. https://www.ipecollaborative.org/assets/core-competencies/IPEC_Core_Competencies_Version_3_2023.pdf

- Price SL, Sim SM, Little V, et al. A longitudinal, narrative study of professional socialisation among health students. Med Education. 2021;55(4):478-485. doi:10.1111/medu.14437

- Pearl R, Wayling B. The telehealth era is just beginning. Harv Bus Rev. 2022;1. Accessed June 1, 2025. https://hbr.org/2022/05/the-telehealth-era-is-just-beginning