Treatment Strategies for Massive Pontine Hemorrhage

Recommended Treatment for Patients with Massive Pontine Hemorrhage: Cases report and review

Somkrit Sripontan, Jackree Thanyanopporn, Kraiwin Rattanarak, Krittika Rattanarak, Chatchada Chowsuntia, Suchanya dejsiri, Sirinard Phraphatphong

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 September 2025

CITATION: Sripontan, S., et al., 2025. Recommended Treatment for Patients with Massive Pontine Hemorrhage: Cases report and review. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(9). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6923

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6923

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Primary pontine hemorrhage poses a significant treatment challenge due to the critical and compact anatomy of the brainstem. Massive PPH is typically associated with poor outcomes, and there is currently no consensus on treatment guidelines. We propose a clinical decisional framework based on radiologic and clinical criteria to identify patients who might benefit from active intervention. In this case series of 14 patients with massive ventral PPH, 5 patients died within the first week due to severe comorbidities. Of the 9 surviving patients, all underwent early tracheostomy and experienced minor complications. Among them, 2 patients with complete anterior pontine involvement on CT scans remained in a long-term vegetative state. The other 7 patients, who showed partial anterior sparing on imaging, demonstrated significant neurological improvement following simple commands by week 4 and achieving partial functional recovery at 6 months. These patients were able to communicate effectively and regained varying degrees of mobility, although all remained dependent on assistance. Our findings support individualized decision-making and suggest that selected patients with massive PPH may benefit from full medical management.

Keywords

pontine hemorrhage, brainstem, treatment, neurological improvement, clinical framework

INTRODUCTION

Primary pontine hemorrhage (PPH) accounts for a significant proportion of hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhages (ICH). Unlike supratentorial hemorrhages, PPH poses unique challenges due to its location within the brainstem, a region that contains ascending and descending tracts, cranial nerve nuclei, and vital centers controlling consciousness, cardiovascular, and respiratory functions. Even small lesions in this area can lead to devastating neurological deficits or death. Infratentorial hemorrhages, including PPH, have consistently been associated with poor outcomes in multiple studies.

Inadequate resuscitation in acute phase cause failure of these vital function. The PPH has among the highest mortality rates ranging from 30% to 90% depending on severity and comorbid conditions. Those who survive often remain in a vegetative state. These are general concepts cause patient s family to take a decision to non-aggressive treatment in massive PPH patients. In general, key prognostic indicators for poor outcomes in ICH include coma on admission, hematoma volume >30 mL, infratentorial hemorrhage, presence of intraventricular hemorrhage, age >80 years, hyperglycemia, and chronic kidney disease. Due to the complex anatomy, previous evidence and grave prognosis, most physicians prefer to palliative or end-of-life care in cases of massive PPH. Decision-making biases may influence the patient s chance of survival.

However, since the publication of a successful case of massive PPH treatment in 2019, there has been increasing interest in identifying patients who may benefit from aggressive management. This report presents our experience managing 14 patients with massive ventral PPH at Mahasarakham Hospital, Thailand, and proposes a clinical decision framework for guiding treatment.

METHODS

Retrospective studies were conducted on all cases of primary parenchymal hemorrhage (PPH) admitted to Mahasarakham Hospital between January 2020 and March 2025. A general physician utilizes a decisional framework (Figure 1) in the emergency department to guide discussions with patients and their families regarding prognosis and chances of survival. The neurosurgeon serves as the primary attending physician during long-term care. Under the hospital s ethics approval license number MSKH_REC 68-01-058 (COA 68/058), data were collected on patient age, sex, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score at admission, hematoma characteristics on initial CT brain imaging, CT brain findings at the fourth week, and modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores at both the fourth week and the sixth month. The study focuses on massive PPH cases, as they pose critical challenges in treatment planning. The decisional framework presented was developed based on a comprehensive literature review in acute stroke management, as described in this section.

Standard ICH scoring systems are not directly applicable to PPH due to anatomical differences. Almost all PPH patients lose consciousness due to reticular activating system compression and/or brainstem edema. So, level of consciousness may not be the first item to evaluation because it may be transient event. Most PPH patients present with sudden loss of consciousness or focal neurological deficits. Non-contrast brain CT is essential for diagnosis, helping differentiate hemorrhagic from ischemic stroke and assess hematoma volume and location. Based on imaging, PPH can be classified into: Favorable prognosis: small (<10 mL), unilateral, dorsal (tegmental) PPH and Poor prognosis: large (>10 mL), ventral (basis pontis) PPH. This study focuses on the latter group: massive ventral PPH because it had the worst prognosis. So, the first step is separated to two groups. Both groups are treated by standard stroke guideline. We adopted the scoring system proposed by Huang et al to guide prognosis and family discussions. It assigns points for hematoma volume and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score. This scoring system is developed to predict 30-day mortality and 90-day outcome. This scoring system is composed of Hematoma volume: <5 mL = 0 points, 5-10 mL = 1 point, >10 mL = 2 points and GCS score: 8-15 = 0 points, 5-7 = 1 point, 3-4 = 2 points. The 30-day mortality rates for patients with a total score of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 2.7%, 31.6%, 42.7%, 81.8%, and 100%, respectively. A total score of 3 implies a high (81.8%) 30-day mortality rate, but some patients may still achieve meaningful recovery. We used GCS to classify patients: GCS <6 (e.g., E1V1M2 M3): poor prognosis that palliative care recommended and GCS 6 (e.g., E2V1M4 or better): full medical management offered. Notably, a motor response of M4 (withdrawal to pain) was considered a key indicator of possible brainstem function preservation. Decorticate and decerebrate response in GCS, M3 and M2, are signs of brainstem injury. So, in our idea, M4 in GCS (withdraw to deep pain stimulation) refers to brainstem still survived. However, every case must take the treatment decision by patients family. Patients selected for full medical support were treated according to the latest American Stroke Association (ASA) and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines. Treatment included: ICU monitoring, Management of intracranial pressure, Respiratory support (early tracheostomy), Blood pressure control, Seizure prophylaxis, Early nutritional support, Infection prevention.

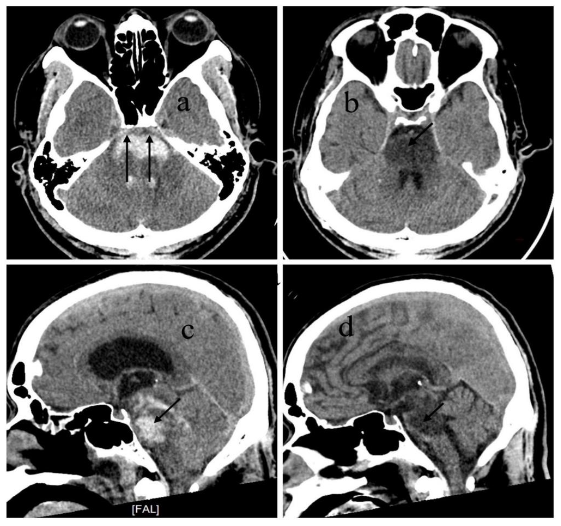

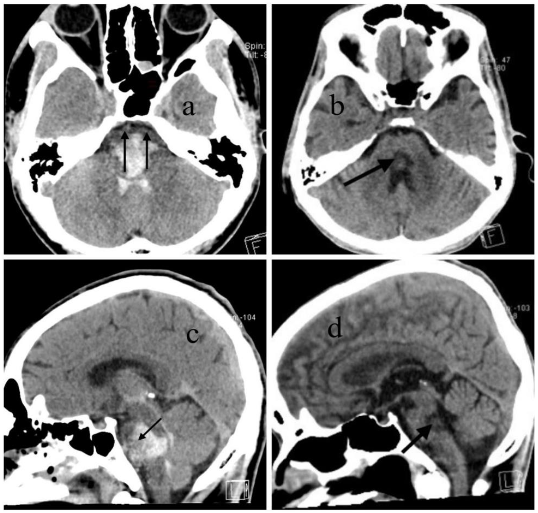

Follow-up CT or MRI was performed in the 3rd-4th week to exclude underlying lesions such as vascular malformations or tumors. The mRS was used to evaluate outcomes at week 4 and month 6. Special attention was given to anterior pontine involvement on initial CT scans. The hypothesis is complete involvement of the anterior pons was associated with poor recovery (vegetative state), while partial sparing correlated with better outcomes.

RESULTS

Between January 2020 and March 2025, a total of 123 patients were diagnosed with brainstem hemorrhage at Mahasarakham Hospital. Among these, 95 patients had primary pontine hemorrhage (PPH). Of the 95 PPH cases: 58 cases were classified as dorsal type, unilateral, or small-volume hemorrhage, which generally resulted in favorable outcomes, consistent with our previous study. Thirty-seven cases were identified as massive ventral PPH, a group associated with poor prognosis. Among the 37 patients with massive ventral PPH: 23 patients were managed with end-of-life or palliative care based on family decision and poor initial clinical condition, 14 patients received full medical treatment per ASA/AHA stroke guidelines and were closely monitored for signs of recovery.

| Sex/Age | Ventral pons ICH | ICH vol. (ml) | CT at 4th week | GCS at admit | mRS 4th wk | mRS 6th mo | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/42* | Total | 70 | Total hypo. | E1V1M3 | 5 | 6 | Cardiac arrest at home at 5th mo. |

| M/33 | Total | 75 | Total hypo. | E1V1M4 | 5 | 5 | Vegetative status |

| M/20** | Subtotal | 72 | Central hypo. | E2V1M4 | 4 | 3 | good command |

| M/36 | Subtotal | 65 | Central hypo. | E1V1M4 | 4 | 4 | good command |

| F/45 | Subtotal | 62 | Central hypo. | E1V1M4 | 4 | 3 | good command |

| M/51 | Subtotal | 50 | Central hypo. | E1V1M4 | 5 | 4 | good command |

| F/56 | Subtotal | 64 | Central hypo. | E1V1M4 | 5 | 4 | good command |

| M/42 | Subtotal | 70 | Central hypo. | E2V1M4 | 4 | 3 | good command |

| F/61 | Subtotal | 66 | Central hypo. | E1V1M4 | 5 | 4 | good command |

| F/71 | Subtotal | 55 | N/a | E1V1M3 | 6 | 6 | AF with arrest |

| M/69 | Total | 68 | N/a | E1V1M4 | 6 | 6 | AF with arrest |

| M/65 | Subtotal | 64 | N/a | E1V1M4 | 6 | 6 | ESRD |

| F/70 | Total | 78 | N/a | E1V1M3 | 6 | 6 | ESRD |

| M/59 | Subtotal | 60 | N/a | E1V1M4 | 6 | 6 | AF with arrest |

All 14 patients received comprehensive stroke care, including: strict blood pressure control (target SBP 140 mmHg), stabilization of vital signs, aggressive management of infections, ventricular drainage when obstructive hydrocephalus was present, early tracheostomy, prompt management of complications. Three patients died during hospitalization due to cardiac arrest associated with atrial fibrillation and failed resuscitation. Two patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) died from volume overload and related complications within the first week. Two surviving patients, who had complete ventral pons involvement, remained in long-term vegetative state despite aggressive treatment and absence of major comorbidities. Seven patients demonstrated partial sparing of the anterior pons on CT. These patients showed improvement in consciousness by week 4, responding to simple commands, and achieved partial functional independence by month 6. At 6 months: all 7 patients were able to communicate effectively. Motor recovery varied: some could ambulate with an ataxic gait, others required a wheelchair for mobility. All required daily assistance for activities of living.

DISCUSSION

Although the brainstem contains dense networks of neurological tracts and vital centers within a compact anatomical space, the initial hematoma observed on CT imaging in primary pontine hemorrhage (PPH) may not represent complete or irreversible injury in all cases. Because the primary functions of the brainstem are autonomic regulation and coordination not cognition and memory, which are functions of the higher brain its damage presents a distinct clinical profile. The extent of hemorrhage seen on the first CT scan typically reflects the acute neurological deficit at presentation, but does not always predict long-term outcomes.

Anatomically, the corticospinal tracts responsible for voluntary motor control are arranged ventromedial to dorsolateral within the pontine basis. In contrast, the cranial nerve nuclei and reticular formation, which control functions such as arousal, autonomic regulation, and coordination, are mainly located in the dorsal pons (tegmentum). When the hematoma completely involves the ventral pons, the corticospinal tracts are severely damaged, often leading to long-term motor deficits or a vegetative state, as seen in two patients in our series. However, when partial sparing of the ventral pons is present, as in seven of our cases, patients showed recovery of consciousness and meaningful motor function over time. These findings suggest that the most anterior part of the pons, which contains the corticospinal tract, is a critical region for predicting long-term outcomes in terms of motor coordination and the severity of motor deficits.

Reticular formation is a complex network of brainstem nuclei and neuron that serve as a major integration and relay center of many vital system. The major functions of reticular formation are arousal, consciousness, circadian rhythm, sleep-wake cycles, coordination of somatic motor movements, cardiovascular and respiratory control, pain modulation, and habituation. However, only ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) that locate at upper pons, midbrain, and lateral hypothalamus lesions are related with alertness and sleep-wake cycles. Damage of bilateral midbrain can result sudden dead. Therefore, the initial level of consciousness is closely related to the degree of damage in these specific brainstem structures. The level of consciousness may be evaluated more accurately once the hematoma has resolved, typically around the fourth week.

Vascular supply of pons is originated from striate branches of paramedian branches of the basilar artery, vertebral artery, and posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA). Studies have shown that PPH often results from rupture of these deep perforating arteries due to chronic hypertension. The rupture leads to high-pressure blood extravasation into the brainstem parenchyma. Massive PPH usually leak from proximal part of striate artery near basilar artery that high pressure. In contrast to ischemic stroke, the long-term lesion after hematoma resolution in ICH may be smaller than the initial bleed. Common lesion sites in PPH include the middle pons, particularly the dorsal half of the pontine base, and the junction between the tegmentum and basis pontis. Therefore, a massive lesion observed on the initial CT brain scan may cause a transient loss of function due to compression from the hematoma. Because these areas are not directly involved in the ARAS, consciousness can be preserved or recovered, depending on the extent of the damage.

Histopathological studies of hematoma from stroke, effect of hematoma to brain has two main mechanisms; physical compression and chemical irritation from degradation products. If hematoma is adequately resorbed, neuronal function may partially recover, especially in cases without severe secondary injury. Animal studies support these findings. Pontine hematomas in rodents typically resolve within three weeks, and survival is possible if gustatory, cardiovascular, and reticular systems remain intact. In hindbrain ischemia models, respiratory and cardiovascular neurons showed greater resistance to ischemia than other brainstem cells. These findings suggest that, with full medical support, it is reasonable to wait for hematoma resolution and assess the potential for neurological recovery.

Our treatment decision framework is designed to assist emergency physicians and general practitioners who often face the responsibility of guiding patients families at the time of diagnosis. It integrates clinical and radiological criteria to determine the feasibility of active treatment. While massive ventral PPH generally carries a poor prognosis, our findings show that not all such cases result in death or vegetative state. Patients with no severe comorbidities and partial sparing of the anterior pons had a better-than-expected outcome, achieving communication, mobility with assistance, and some degree of independence.

CONCLUSION

Massive primary pontine hemorrhage is commonly associated with a poor prognosis. However, our case series demonstrates that functional recovery is possible in select patients. Specifically: Patients with partial sparing of the anterior ventral pons, and no severe comorbidities, showed significantly better outcomes than predicted. Total anterior pons involvement was associated with persistent vegetative state, even in otherwise healthy individuals. Further studies with larger sample sizes and prospective design are needed to validate these findings and refine the proposed decision-making framework.

REFERENCES

- Mangold SA, Das JM. Neuroanatomy, Reticular Formation. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed July 29, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556102/

- Milsom WK, Chatburn J, Zimmer MB. Pontine influences on respiratory control in ectothermic and heterothermic vertebrates. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;143(2-3):263-280. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2004.05.008

- An SJ, Kim TJ, Yoon BW. Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Clinical Features of Intracerebral Hemorrhage: An Update. J Stroke. 2017;19(1):3-10. doi:10.5853/jos.2016.00864

- Ss W, Y Y, J V, et al. Management of brainstem haemorrhages. Swiss medical weekly. 2019;149. doi:10.4414/smw.2019.20062

- Behrouz R. Prognostic factors in pontine haemorrhage: A systematic review. Eur Stroke J. 2018;3(2):101-109. doi:10.1177/2396987317752729

- Wessels T, Möller-Hartmann W, Noth J, Klötzsch C. CT findings and clinical features as markers for patient outcome in primary pontine hemorrhage. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25(2):257-260.

- K B, T A, M K, Y C, U U. Clinical and neuroradiological predictors of mortality in patients with primary pontine hemorrhage. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2005;108(1). doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.02.007

- Sripontan S. Good Outcome in a Patient with Massive Pontine Hemorrhage. Asian J Neurosurg. 2019;14(3):992-995. doi:10.4103/ajns.AJNS_295_18

- Huang KB, Ji Z, Wu YM, Wang SN, Lin ZZ, Pan SY. The prediction of 30-day mortality in patients with primary pontine hemorrhage: a scoring system comparison. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(9):1245-1250. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03724.x

- Huang K, Ji Z, Sun L, et al. Development and Validation of a Grading Scale for Primary Pontine Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2017;48(1):63-69. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015326

- Chung CS, Park CH. Primary pontine hemorrhage: a new CT classification. Neurology. 1992;42(4):830-834. doi:10.1212/wnl.42.4.830

- Jang JH, Song YG, Kim YZ. Predictors of 30-day mortality and 90-day functional recovery after primary pontine hemorrhage. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26(1):100-107. doi:10.3346/jkms.2011.26.1.100

- Nishizaki T, Ikeda N, Nakano S, Sakakura T, Abiko M, Okamura T. Factors Determining the Outcome of Pontine Hemorrhage in the Absence of Surgical Intervention. Open Journal of Modern Neurosurgery. 2012;2(2):17-20. doi:10.4236/ojmn.2012.22004

- Murata Y, Yamaguchi S, Kajikawa H, Yamamura K, Sumioka S, Nakamura S. Relationship between the clinical manifestations, computed tomographic findings and the outcome in 80 patients with primary pontine hemorrhage. J Neurol Sci. 1999;167(2):107-111. doi:10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00150-1

- Russell B, Rengachary SS, McGregor D. Primary pontine hematoma presenting as a cerebellopontine angle mass. Neurosurgery. 1986;19(1):129-133. doi:10.1227/00006123-198607000-00023

- Ye Z, Huang X, Han Z, et al. Three-year prognosis of first-ever primary pontine hemorrhage in a hospital-based registry. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22(7):1133-1138. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2014.12.024

- Knight J, Decker LC. Decerebrate and Decorticate Posturing. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed August 6, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559135/

- Hemphill JC, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2015;46(7):2032-2060. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000069

- Greenberg SM, Ziai WC, Cordonnier C, et al. 2022 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2022;53(7):e282-e361. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000407

- Broderick JP, Adeoye O, Elm J. The Evolution of the Modified Rankin Scale and Its Use in Future Stroke Trials. Stroke. 2017;48(7):2007-2012. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017866

- S S, J I, W S. ปัจจัยที่มีผลต่อการพยากรณ์การรักษาในผู้ป่วยที่มีภาวะเลือดออกบริเวณก้าสมองระดับพอนส์ในโรงพยาบาลมหาสารคาม Journal of The Department of Medical Services. 2020;45(3):76-81.

- Sridhar S, Khamaj A, Asthana MK. Cognitive neuroscience perspective on memory: overview and summary. Front Hum Neurosci. 2023;17:1217093. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2023.1217093

- Ackerman S. Major Structures and Functions of the Brain. In: Discovering the Brain. National Academies Press (US); 1992. Accessed August 31, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK234157/

- Hong JH, Son SM, Jang SH. Somatotopic location of corticospinal tract at pons in human brain: a diffusion tensor tractography study. Neuroimage. 2010;51(3):952-955. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.063

- Rahman M, Tadi P. Neuroanatomy, Pons. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed July 29, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560589/

- Wang D. Reticular formation and spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2009;47(3):204-212. doi:10.1038/sc.2008.105

- Jang SH, Chang CH, Jung YJ, Kwon HG. Hypersomnia due to injury of the ventral ascending reticular activating system following cerebellar herniation: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(1):e5678. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000005678

- Roob G, Schmidt R, Kapeller P, Lechner A, Hartung HP, Fazekas F. MRI evidence of past cerebral microbleeds in a healthy elderly population. Neurology. 1999;52(5):991-994. doi:10.1212/wnl.52.5.991

- Kwa VI, Franke CL, Verbeeten B, Stam J. Silent intracerebral microhemorrhages in patients with ischemic stroke. Amsterdam Vascular Medicine Group. Ann Neurol. 1998;44(3):372-377. doi:10.1002/ana.410440313

- Zafar A, Khan FS. Clinical and radiological features of intracerebral haemorrhage in hypertensive patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58(7):356-358.

- Keep RF, Hua Y, Xi G. Intracerebral haemorrhage: mechanisms of injury and therapeutic targets. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(8):720-731. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70104-7

- The Structural Factor of Hypertension | Circulation Research. Accessed August 7, 2025. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303596?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

- Evans MRB, Weeks RA. Putting pontine anatomy into clinical practice: the 16 syndrome. Practical Neurology. 2016;16(6):484-487. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2016-001367

- Jeong JH, Yoon SJ, Kang SJ, Choi KG, Na DL. Hypertensive Pontine Microhemorrhage. Stroke. 2002;33(4):925-929. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000013563.73522.CB

- Nakajima K. Clinicopathological study of pontine hemorrhage. Stroke. 1983;14(4):485-493. doi:10.1161/01.str.14.4.485

- Nakajima K, Ito Z, Hen R, Suzuki A, Fukasawa H. [Clinicopathological study of pontile hemorrhage–II. Pathological aspects (author’s transl]. No To Shinkei. 1977;29(11):1157-1165.

- Dinsdale HB. SPONTANEOUS HEMORRHAGE IN THE POSTERIOR FOSSA.A STUDY OF PRIMARY CEREBELLAR AND PONTINE HEMORRHAGES WITH OBSERVATIONS ON THEIR PATHOGENESIS. Arch Neurol. 1964;10:200-217. doi:10.1001/archneur.1964.00460140086011

- Wilkinson DA, Pandey AS, Thompson BG, Keep RF, Hua Y, Xi G. Injury mechanisms in acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Neuropharmacology. 2018;134(Pt B):240-248. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.09.033

- Song S, Hua Y, Keep RF, Hoff JT, Xi G. A New Hippocampal Model for Examining Intracerebral Hemorrhage-Related Neuronal Death. Stroke. 2007;38(10):2861-2863. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.488015

- Zhang Y, Khan S, Liu Y, et al. Modes of Brain Cell Death Following Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Front Cell Neurosci. 2022;16:799753. doi:10.3389/fncel.2022.799753

- Lekic T, Krafft PR, Coats JS, Obenaus A, Tang J, Zhang JH. Infratentorial Strokes for Posterior Circulation Folks: Clinical Correlations for Current Translational Therapeutics. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2(2):144-151. doi:10.1007/s12975-011-0068-2

- Hata R, Matsumoto M, Hatakeyama T, et al. Differential vulnerability in the hindbrain neurons and local cerebral blood flow during bilateral vertebral occlusion in gerbils. Neuroscience. 1993;56(2):423-439. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(93)90343-e