Machine Learning in Biomarker Discovery for Precision Medicine

Machine learning enhances biomarker discovery: From multi-omics to functional genomics.

Xinyang Zhang¹, Ali Rahnavard¹, Keith A. Crandall¹

- Computational Biology Institute, Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Milken Institute School of Public Health, The George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052

ORCID:

Ms. Zhang: 0000-0001-7713-8874

Dr. Rahnavard: 0000-0002-9710-0248

Dr. Crandall: 0000-0002-0856-3389

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 August 2025

CITATION: Zhang, X., Rahnavard, A., Crandall, K. A., Machine learning enhances biomarker discovery: From multi-omics to functional genomics. Medical Research Archives, [online]13(8).https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6888

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open- access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8. 6888

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Importance: Biomarkers are critical for precision medicine, supporting disease diagnosis, prognosis, personalized treatments, and monitoring. Traditional biomarker discovery methods, which often focus on single genes or proteins, face several challenges, including limited reproducibility, a limited ability to integrate multiple data streams, high false-positive rates, and inadequate predictive accuracy. Machine learning and deep learning methods, and large language models, paired with advancements in omics technologies, address these limitations by analyzing large, complex multi-omics datasets to identify more reliable and clinically useful biomarkers.

Observations: Machine learning and deep learning have proven effective in biomarker discovery by integrating diverse and high-volume data types, such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, imaging, and clinical records. These approaches successfully identify diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers across fields, such as oncology, infectious diseases, neurological disorders, and autoimmune diseases. Newer methodological developments include approaches to identify functional biomarkers, notably biosynthetic gene clusters, crucial for discovering antibiotics and anticancer drugs. Key artificial intelligence (AI) techniques include neural networks, transformers, large language models, and feature selection methods, which are finding more and more application to omics data and in clinical settings. However, challenges remain regarding data quality, biological complexity, model interpretability, validation, and generalization. Regulatory and ethical considerations also impact clinical adoption, emphasizing the importance of validated, trustworthy, and explainable AI methods.

Conclusions and Relevance: Machine learning, deep learning, and AI agent-based approaches significantly enhance biomarker discovery, providing valuable biological insights and advancing precision medicine. Future research should focus on directly linking genomic data to functional outcomes, particularly with biosynthetic gene clusters and non-coding RNAs. Rigorous validation, model interpretability, and regulatory compliance are essential for clinical implementation. These advancements promise to improve personalized treatment strategies and patient outcomes.

Keywords: Biomarker Discovery, Machine Learning, Deep Learning, AI-based, Multi-Omics Integration, Precision Medicine, Functional Biomarkers, Biosynthetic Gene Clusters, Explainable AI, Trustworthy AI

Introduction

Biomarkers are measurable indicators of biological processes, pathological states, and/or responses to therapeutic interventions. In precision medicine, biomarkers are critically important as they facilitate accurate diagnosis, effective risk stratification, continuous disease monitoring, and personalized treatment decisions, particularly for complex diseases such as cancer. Precision medicine aims to deliver targeted therapies tailored to individual genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors, thus maximizing treatment efficacy while minimizing potential adverse effects. The traditional approach to biomarker discovery has predominantly focused on single molecular features, such as individual genes or proteins, quantitative trait loci, and/or single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with disease as identified by genome wide association studies.

However, this conventional methodology faces significant challenges, including limited reproducibility, high false-positive rates, inadequate predictive accuracy, and increased costs due to the inherent complexity and biological heterogeneity of diseases. Such single-feature approaches are frequently inadequate in capturing the multifaceted biological networks that underpin disease mechanisms, particularly in complex and heterogeneous conditions like cancer.

The limitations of traditional biomarker discovery approaches have prompted the exploration and integration of advanced computational techniques, notably machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL). These methods represent a substantial shift from traditional analytical techniques by their capacity to handle and interpret vast and complex biological datasets, known collectively as multi-omics data.

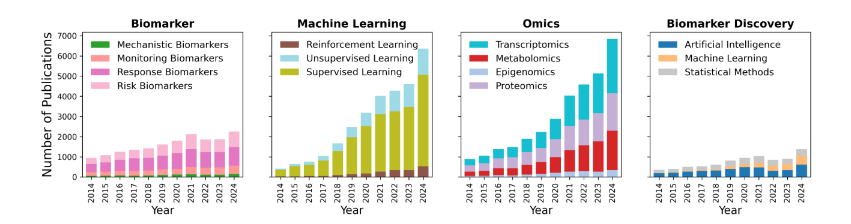

Multi-omics approaches integrate data from diverse biological layers, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, imaging data, and clinical records, thus providing comprehensive molecular profiles and facilitating the identification of highly predictive biomarkers. Machine learning based methodologies have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in analyzing such large-scale datasets, enabling the identification of intricate patterns and interactions among various molecular features that were previously unrecognized or poorly understood. Indeed, as a consequence, the adoption and expansion of computational techniques, particularly machine learning and omics-based strategies, reflect an ongoing transition toward integrative and data-intensive biomarker discovery approaches.

Furthermore, ML and DL based biomarker discovery is not confined solely to conventional diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Recent developments have expanded the scope of ML and DL applications to include functional biomarkers, such as biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). BGCs are groups of genes that encode the enzymatic machinery necessary to produce specialized metabolites, many of which have significant therapeutic potential, such as antibiotics and anticancer agents. Thus, the computational prediction of BGCs using advanced deep learning models presents a novel dimension in biomarker discovery, directly linking microbial genomic capabilities to functional outcomes.

Despite these advancements, the integration of ML and DL techniques in biomarker discovery is not without controversy or challenges. Key concerns revolve around data quality issues, including limited sample sizes, noise, batch effects, and biological heterogeneity. These data-related limitations can severely impact model performance, leading to issues such as overfitting and reduced generalizability. Additionally, the interpretability of ML models remains a significant hurdle, as many advanced algorithms function as “black boxes,” making it difficult to elucidate how specific predictions are derived. This lack of interpretability poses practical barriers to clinical adoption, where transparency and trust in predictive models are essential. Another critical issue is the insufficient use of rigorous external validation strategies. Biomarkers identified through computational methods must undergo stringent validation using independent cohorts and experimental (wet-lab) methods to ensure reproducibility and clinical reliability.

Indeed, both the algorithmic pipeline, but especially the data used in training AI approaches, as well as validation approaches, can all impact the trustworthiness of the AI output. Ethical and regulatory considerations also significantly influence the deployment of ML-derived biomarkers into clinical practice. Biomarkers used for patient stratification, therapeutic decision making, or disease prognosis must comply with rigorous standards set by regulatory bodies such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The dynamic nature of ML-driven biomarker discovery, where models continuously evolve with new data, presents particular challenges for regulatory oversight and demands adaptive yet strict validation and approval frameworks.

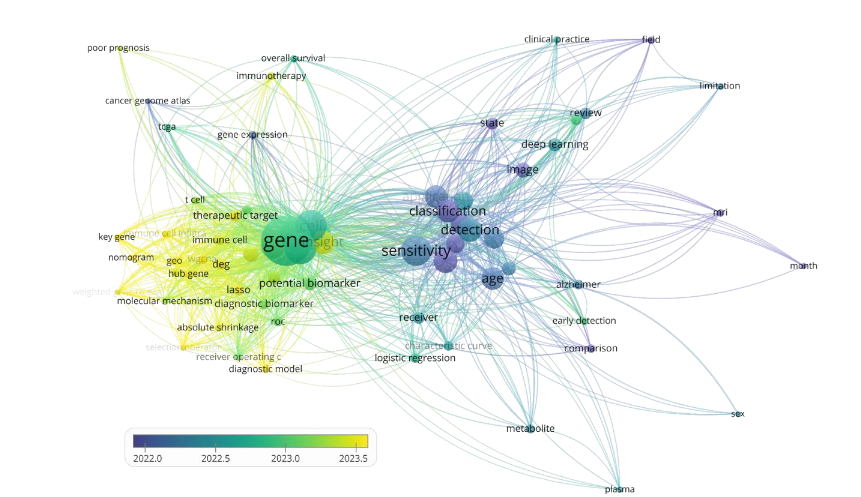

This review assesses how ML and DL technologies enhance biomarker discovery, particularly through integrating multi-omics data and functional genomics approaches. To ground this effort, we conducted a co-occurrence network analysis of recent PubMed-indexed literature, which revealed increasingly dense linkages among keywords such as gene expression, sensitivity, classification, therapeutic targets, and immune profiling, highlighting the growing interconnections between machine learning, omics technologies, and clinical biomarker research.

Motivated by these interconnections, we systematically review the current landscape of biomarker discovery studies across data modalities, modeling approaches, and application domains. This review outlines methodological advances and future opportunities in the field by addressing key challenges, exploring functional biomarker developments such as biosynthetic gene clusters, and emphasizing the importance of interpretability and clinical validation.

Biomarker types and application domains

Biomarkers can be categorized broadly into risk, diagnostic, prognostic, predictive, and pharmacodynamic types. Diagnostic biomarkers identify disease presence, prognostic biomarkers forecast disease progression, and predictive biomarkers estimate treatment efficacy. Machine learning applications span across various disease areas, with significant advancements in oncology, particularly in breast, lung, and colon cancers, among others. In addition to cancer, ML-based biomarker discovery is expanding into infectious diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and chronic inflammatory diseases, illustrating the versatility of these methodologies. Of particular interest is the emergence of microbiome and functional biomarkers, where ML methods are instrumental in predicting complex biological phenomena such as BGCs, crucial for novel antibiotic and anticancer compound discovery. Biomarkers serve as quantifiable indicators of biological states or conditions, offering critical insights for disease diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic response prediction. In the era of precision medicine, machine learning and deep learning have accelerated the discovery and application of diverse biomarker types across a wide range of clinical and research domains.

ML-based biomarker discovery spans a broad spectrum of application domains, including but not limited to:

- Cancer – Biomarkers for early detection, stratification of tumor subtypes, and response to immunotherapy are being actively developed using ML models trained on genomic, epigenomic, and histopathological data.

- Infectious diseases – Machine learning has been employed to identify host and microbial biomarkers that distinguish between viral and bacterial infections or predict disease severity in infections such as COVID-19 and tuberculosis.

- Neurological and psychiatric disorders – Functional and structural neuroimaging data, combined with ML, are being used to identify biomarkers for conditions like depression and schizophrenia.

- Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases – Machine learning models help identify immunological markers that distinguish between overlapping clinical syndromes, improving diagnostic precision.

Across these diverse application areas, ML-based biomarker discovery is increasingly enabling disease endotyping—the classification of subtypes based on shared molecular mechanisms rather than solely clinical symptoms. This mechanistic approach supports more precise patient stratification, therapy selection, and understanding of disease heterogeneity.

Data Types Utilized

ML-driven biomarker discovery integrates diverse data types, notably genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, imaging data, patient data (clinical, electronic health record [EHR], demographic), and metagenomics. Omics technologies, such as DNA microarrays and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), provide rich gene expression datasets essential for identifying differential gene expression and molecular signatures associated with specific disease states or treatment responses.

Imaging data, including radiology and histopathology, offer high-density information amenable to ML, particularly DL methods. DL models, for example, can extract hidden prognostic and predictive information directly from routine histological images, significantly enhancing the traditional pathology workflows. Metagenomic and microbial genomic data have also become vital, especially for studying microbiome-related biomarkers and their influence on human health and diseases. ML techniques applied to metagenomic and metabolomic data are increasingly uncovering microbial signatures linked with disease phenotypes, including biomarkers predicting functional traits like biosynthetic gene clusters.

An emerging frontier in biomarker research is the study of microbiome-derived and functional biomarkers. The recognition of the microbiome’s impact on health has spurred the application of ML to identify microbial pathways involved in metabolite production, revealing potential therapeutic targets. These approaches integrate taxonomic, functional, and ecological/environmental data, expanding the biomarker landscape beyond the human genome to include the broader holobiont.

Machine Learning Methodologies

Machine learning methodologies in biomarker discovery encompass both supervised and unsupervised approaches. Supervised learning trains predictive models on labeled datasets, aiming to accurately classify disease status or predict clinical outcomes. Commonly used supervised techniques include support vector machines, which identify optimal hyperplanes for separating classes, making them effective for small sample, high dimensional omics data; random forests, ensemble models that aggregate multiple decision trees, providing robustness against noise and overfitting; and gradient boosting algorithms (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM), which iteratively correct previous prediction errors for superior accuracy but require careful tuning to avoid overfitting.

In contrast, unsupervised learning explores unlabeled datasets to discover inherent structures or novel subgroupings without predefined outcomes. These methods are invaluable for endotyping, which classifies diseases based on underlying biological mechanisms rather than purely clinical symptoms and includes clustering methods such as k-means and hierarchical clustering, and dimensionality reduction approaches like principal component analysis.

Deep learning architectures, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNN) and recurrent neural networks (RNN), are especially well suited for complex biomedical data. CNNs utilize convolutional layers to identify spatial patterns, making them highly effective for imaging data (e.g., histopathology), whereas RNNs utilize a recurrent architecture that could help maintain an internal memory of previous inputs, allowing them to understand context and dependencies within sequential information. This is especially important in biomedical data that changes over time, as it enables RNNs to capture temporal dynamics and patterns crucial for predictive and diagnostic tasks in healthcare settings, such as prognosis or treatment response prediction. Machine learning approaches vary significantly across different omics data types, with specific methodologies being optimized for different biological data structures and applications.

| Omics Data | ML Techniques | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics | Feature selection (e.g., LASSO); SVM; Random Forest; XGBoost | Gene expression biomarkers, cancer subtype classification |

| Genomics | Logistic Regression; Random Forest; Gradient Boosting | Mutation-based risk models, variant prioritization |

| Proteomics | Support Vector Machine; Deep Neural Network; KNN | Protein signature for early cancer detection |

| Metabolomics | PCA + Clustering (e.g., k-means, hierarchical); LDA; Decision Trees | Treatment response prediction, disease risk scoring |

| Multi-omics | Multi-view Learning; Deep Auto-encoders; Network-based ML; Bayesian Learning | Integrative biomarker discovery, patient stratification, longitudinal modeling |

Feature selection methods are crucial in reducing high-dimensional noise inherent in omics data. Embedded methods like LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) integrate feature selection into the training process by applying regularization penalties to shrink the coefficients of irrelevant features toward zero. Wrapper methods such as recursive feature elimination (RFE) treat feature selection as a separate step, iteratively evaluating subsets of features based on model performance. While wrapper methods can yield highly optimized feature sets, they typically require more computational resources than embedded methods.

Model training involves tuning parameters to minimize predictive error on labeled training datasets. A major challenge is avoiding bias, overfitting, and data imbalance, problems arising when models learn dataset-specific noise rather than generalizable signals. Strategies to mitigate these issues include regularization, feature scaling, dimensionality reduction, training-validation-testing splits, cross-validation (e.g., k-fold), early stopping techniques, and external validation on independent patient cohorts.

Model performance is evaluated using metrics such as the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC), measuring the trade-off between sensitivity (true positives) and specificity (true negatives); accuracy, indicating the proportion of correct predictions; precision, reflecting the proportion of true positives among predicted positives; and recall, quantifying the proportion of actual positives correctly identified. Each metric provides complementary insights, particularly when dealing with imbalanced data.

Finally, implementing robust and reproducible biomarker discovery pipelines is enhanced by utilizing cloud computing platforms (e.g., AWS, Azure, Google Cloud Platform) and reproducible pipeline frameworks (e.g., Nextflow, Snakemake, Terra, Luigi, AWS HealthOmics, Workflow Description Language, Partek Flow). These technologies support scalable analysis, rigorous validation, transparent reporting, and streamlined integration of ML-derived biomarkers into clinical workflows. For example, the Terra platform, developed by the Broad Institute in collaboration with Google Cloud, has been widely adopted in genomic studies to run portable workflows such as GATK and RNA-seq-based biomarker analyses, enabling researchers to scale across cohorts and share reproducible results with collaborators in real time.

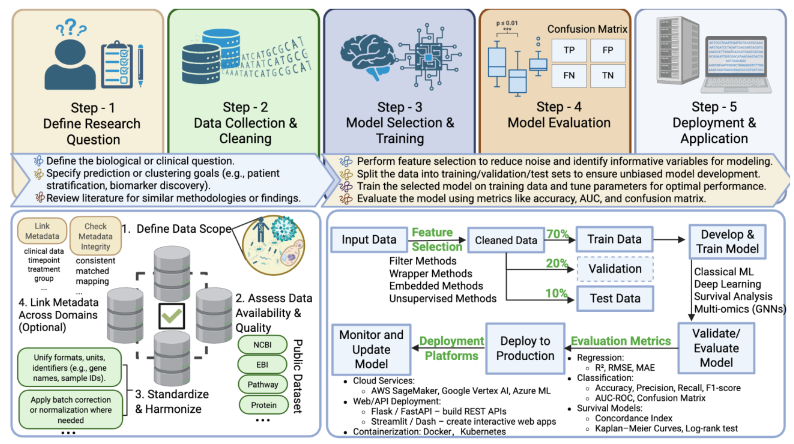

Together, careful attention to methodological clarity, rigorous training and validation procedures, and interpretability of ML models ensures the development of clinically relevant, generalizable, and ethically sound biomarkers, ultimately advancing precision medicine and personalized healthcare solutions. To build a robust ML pipeline for biomarker discovery, several key steps are essential: clearly defining the clinical or biological question, collecting and preprocessing data, selecting informative features, training and validating the model, and deploying it strategically. First, define a specific research goal, then integrate and preprocess multi-omics data by standardizing metadata, correcting batch effects, and normalizing datasets. Feature selection plays a critical role in reducing dimensionality and improving model performance. Common approaches include filter methods (e.g., mutual information, ANOVA), wrapper methods (e.g., recursive feature elimination), embedded methods (e.g., LASSO, tree-based importance from random forests), and unsupervised methods (e.g., PCA, autoencoders). Next, choose and train suitable models, including Random Forest, SVM, XGBoost, or deep learning methods (CNN, RNN), which are tailored to the data type. Validate model performance using train-test splits, cross-validation, or external datasets, employing metrics like AUC-ROC, accuracy, precision, and recall. Finally, deploy the model using scalable cloud platforms, ensuring continuous monitoring, retraining, and updates to maintain accuracy and clinical relevance over time.

Functional Biomarker Discovery: Deep Learning for Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Prediction

Biosynthetic gene clusters are groups of genes co-localized in microbial genomes that collectively encode pathways for synthesizing specialized metabolites. These metabolites often possess significant therapeutic potential, making BGCs invaluable in drug discovery and microbial functional characterization. BGCs also serve as functional biomarkers reflecting microbial metabolic capacity, critical for understanding host-microbe interactions and discovering novel antimicrobial compounds.

Deep learning has revolutionized the prediction and characterization of BGCs through several advanced models. Approaches include DeepBGC, which leverages Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) networks. These are recurrent neural networks that process input sequences in both forward and backward directions to identify and classify BGCs based on sequence patterns and contextual dependencies. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) based models such as e-DeepBGC offer superior performance in capturing local sequence patterns. Transformer-based architectures like BERT have recently been adapted for BGC prediction, improving prediction accuracy significantly by using attention mechanisms to weigh relationships between all parts of a sequence simultaneously. They improve accuracy in identifying non-linear and long-range dependencies within genomic data, capabilities that traditional RNNs and CNNs may miss. Ensemble methods, which combine predictions from multiple deep learning models (e.g., BiLSTM, CNN, and transformer models), have shown promise in boosting robustness and generalization.

The application of DL-based BGC prediction has been transformative in natural product and microbiome research, leading to discoveries of novel antimicrobial compounds.

| Year | Training Set | Model-Name | Level | Pretrained | Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 3376 reference genome | DeepBGC | Pfam | NO | Bi-LSTM + RNN |

| 2020.7 | 6200 full genome + 18576 draft genome | BiGCARP | Pfam | YES | ESM-1b: embedding Dilated 1D-CNN on ByteNet & CARP |

| 2022.8 | 1,974 validated BGC sequences + 8,108 non-BGC sequences | e-DeepBGC | Pfam | NO | CNN+Bi-LSTM |

| 2023 | 1,355 MIBiG v3.0 (+) + RefSeq bacterial genomes(-) | BGC-Prophet | Gene | YES | Transformer – ESM (use gene as token) |

| 2024 | DeepBGC(-)+MiBIG(+) | BGCCGB | Pfam | NO | GCN (Graph Convolutional Network) + BERT |

| 2025.1 | Metagenomics | GenomeOcean | YES | Transformer, decoder only, Byte-Pair Encoding tokenizer | |

| 2025.3 | MiBIG(+) + Cryptic BGCs dataset(unverified) | DeepSeMS | Pfam | NO | Transformer-based Seq2Seq Model, ESM |

Despite these successes, significant validation bottlenecks persist. Experimental verification of predicted BGC functions remains labor-intensive and costly. Generalization to novel or atypical BGC types, such as cryptic gene clusters with non-canonical domain architectures or those from rare microbial taxa, is particularly difficult. For instance, models trained predominantly on Streptomyces genomes may underperform when applied to BGCs from marine organisms, highlighting the need for continual retraining on more taxonomically and functionally diverse datasets or better matching training data to a specific application.

A critical need remains for enhanced biological interpretability of DL models to improve their integration with experimental workflows. The development and application of explainable AI methods (XAI) present regulatory necessities and unique research opportunities. Emerging researchers are encouraged to incorporate interpretability techniques such as attention mechanisms or feature attribution tools, notably SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations). SHAP assigns importance values to individual features based on their contribution to predictions, drawing on principles from cooperative game theory, while LIME provides local approximations of complex models through simpler, interpretable models around specific data points. These techniques clarify which sequence regions or domains drive model predictions, prioritize genes for experimental validation, and aid the functional annotation of unknown BGC components. This emphasis on transparency and interpretability will not only bridge computational predictions and experimental validation but also facilitate clinical adoption and foster trust in ML-driven biomarker discovery.

Integrating DL-based BGC predictions with multi-omics data, including host genomics, metabolomics, and clinical phenotypes, offers considerable potential. Such integration can lead to microbiome-informed biomarkers that accurately predict disease progression or therapeutic response, advancing personalized medicine strategies. Future research should aim to develop comprehensive platforms integrating microbial genomic data with host clinical parameters to yield actionable insights into patient stratification and treatment optimization.

Complementing these deep learning techniques, recent advancements leveraging Large Language Model (LLM) and agent-based frameworks have emerged as additional powerful tools in biomarker discovery workflows. AI agents, exemplified by Biomni, autonomously execute complex research tasks by integrating diverse data sources and computational resources, significantly enhancing biomedical workflows. These AI tools have demonstrated robust capabilities in various biomedical applications such as causal gene prioritization, drug repurposing, rare disease diagnosis, microbiome analysis, and molecular cloning. Platforms like PandaOmics utilize advanced LLMs (e.g., ChatGPT and Gemini) to interpret multi-modal datasets, construct biological networks and knowledge graphs, and effectively identify novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers.

Conclusions

Critical opportunities and challenges emerge as biomarker discovery advances through machine learning. Traditionally, biomarker discovery has concentrated on identifying correlations between molecular markers and clinical outcomes. Datasets typically have more variables or features than available samples, leading to underpowered analyses and increasing the risk of overfitting. Data noise, including image artifacts, batch effects, and hybridization errors, significantly impacts the reliability of biomarker identification. Biological heterogeneity within datasets, such as continuous or categorical molecular profiles and features spread across multiple modalities, complicates integration and meaningful analysis, requiring robust imputation methods for missing data. Incorporating causal inference frameworks, such as potential outcomes or counterfactual modeling, can significantly enhance our comprehension of biomarkers’ underlying biology and disease relevance. Potential outcomes modeling involves explicitly defining hypothetical scenarios (counterfactuals), such as the effect of a specific genetic mutation or treatment on disease progression. Counterfactual modeling compares observed outcomes with hypothetical alternatives, aiming to uncover cause-and-effect relationships rather than mere associations. By leveraging these causal inference approaches, researchers can distinguish biomarkers that truly influence disease progression or treatment responses from those that are simply correlated due to confounding factors, ultimately guiding more targeted and biologically relevant interventions.

A promising research area involves predicting biomarker functionality directly from raw sequence or omics data. While many studies currently utilize protein or protein-family levels (e.g., Biosynthetic Gene Clusters) as an intermediate step, predictive models could bridge existing gaps by characterizing rare mutations, non-coding RNAs (such as lncRNAs and circRNAs), and other poorly understood molecular entities. Integrating multiple omics layers, including genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data that could further uncover interconnected biological pathways and functional signatures, offering a richer context beyond isolated molecular features. Furthermore, novel methodologies should prioritize constructing functional biomarker signatures through graph-based and network-oriented machine learning approaches. Techniques such as Graph Convolutional Network (GCN), Graph Attention Network (GAT), and network embedding methods (e.g., node2vec) explicitly model molecular interactions and relationships, enhancing clinical interpretability and biological relevance. For instance, GCNs incorporate gene or protein interaction networks directly into predictive models, enabling the identification of biomarkers that are functionally interconnected rather than isolated. GATs further improve interpretability by weighting the importance of neighboring nodes through attention mechanisms. Methods like node2vec capture complex network relationships by transforming nodes into continuous embeddings, preserving structural information critical for pathway-level interpretation.

Validation remains a critical challenge. Researchers must rigorously address validation biases, ensuring biomarker models are externally validated and perform reliably in independent clinical contexts. Misclassification of prognostic versus predictive biomarkers carries significant clinical implications and must be actively mitigated. Ensuring close alignment between training populations and intended clinical cohorts in terms of demographics, disease stage, genetic background, and clinical settings is essential for predictive accuracy, health equity, and fairness. Additionally, synthetic and simulation-based datasets, especially through Digital Twin technology, offer powerful platforms to benchmark biomarker methodologies, systematically test hypotheses, and iteratively refine models based on real-world data. Finally, longitudinal and real-time biomarker discovery, leveraging survival analysis and dynamic Bayesian networks, represents a largely untapped yet promising direction, enabling early detection and personalized therapeutic strategies. Collectively, these avenues provide ample opportunities for new investigators to advance biomarker research, laying the groundwork for impactful contributions in precision medicine.

Taken together, these avenues provide ample opportunities for new investigators to advance biomarker research, laying the groundwork for impactful contributions in precision medicine and ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement:

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation award number 2109688 to AR and KAC.

Table of Abbreviations

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| BPE | Byte-Pair Encoding |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Networks |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| BCG | Biosynthetic Gene Cluster |

| CARP | Convolutional Auto-encoding Representations of Proteins |

| Pfam | Protein Families database |

| – | Negative Samples |

| + | Positive Samples |

| ESM | Evolutionary Scale Modeling |

| MiBIG | Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Database |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| Seq2Seq | Sequence to Sequence |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| DT | Digital Twin |

References:

- Ahmad A, Imran M, Ahsan H. Biomarkers as Biomedical Bioindicators: Approaches and Techniques for the Detection, Analysis, and Validation of Novel Biomarkers of Diseases. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(6). doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15061630

- Johnson KB, Wei WQ, Weeraratne D, et al. Precision Medicine, AI, and the Future of Personalized Health Care. Clinical and Translational Science. 2021;14(1):86-93.

- Su J, Yang L, Sun Z, Zhan X. Personalized Drug Therapy: Innovative Concept Guided With Proteoformics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2024;23(3):100737.

- Hong S, Prokopenko D, Dobricic V, et al. Genome-wide association study of Alzheimer’s disease CSF biomarkers in the EMIF-AD Multimodal Biomarker Discovery dataset. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):403.

- Visscher PM, Wray NR, Zhang Q, et al. 10 years of GWAS discovery: Biology, function, and translation. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101(1):5-22.

- Safari F, Kehelpannala C, Safarchi A, Batarseh AM, Vafaee F. Biomarker Reproducibility Challenge: A Review of Non-Nucleotide Biomarker Discovery Protocols from Body Fluids in Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(10). doi:10.3390/cancers15102780

- Kraljevic S, Stambrook PJ, Pavelic K. Accelerating drug discovery. EMBO reports. Published online September 1, 2004. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400236

- Wang RC, Wang Z. Precision Medicine: Disease Subtyping and Tailored Treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(15). doi:10.3390/cancers15153837

- Ottaiano A, Ianniello M, Santorsola M, et al. From Chaos to Opportunity: Decoding Cancer Heterogeneity for Enhanced Treatment Strategies. Biology (Basel). 2023;12(9). doi:10.3390/biology12091183

- Chen C, Wang J, Pan D, et al. Applications of multi-omics analysis in human diseases. MedComm (2020). 2023;4(4):e315.

- Yetgin A. Revolutionizing multi-omics analysis with artificial intelligence and data processing. Quantitative Biology. 2025;13(3):e70002.

- Athieniti E, Spyrou GM. A guide to multi-omics data collection and integration for translational medicine. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;21:134-149.

- Role of artificial intelligence in revolutionizing drug discovery. Fundamental Research. Published online May 9, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.fmre.2024.04.021

- Choudhary K, DeCost B, Chen C, et al. Recent advances and applications of deep learning methods in materials science. npj Computational Materials. 2022;8(1):1-26.

- pubSight. Github Accessed July 9, 2025. https://github.com/omicsEye/pubSight

- Website. doi:10.1136/bmj.h3449

- Atanasov AG, Zotchev SB, Dirsch VM, Supuran CT. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2021;20(3):200-216.

- Martinet L, Naômé A, Deflandre B, et al. A Single Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Is Responsible for the Production of Bagremycin Antibiotics and Ferroverdin Iron Chelators. mBio. 2019;10(4). doi:10.1128/mBio.01230-19

- A survey of the biosynthetic potential and specialized metabolites of archaea and understudied bacteria. Current Research in Biotechnology. 2023;5:100117.

- Molujin AM, Abbasiliasi S, Nurdin A, Lee PC, Gansau JA, Jawan R. Bacteriocins as Potential Therapeutic Approaches in the Treatment of Various Cancers: A Review of In Vitro Studies. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19). doi:10.3390/cancers14194758

- Rios-Martinez C, Bhattacharya N, Amini AP, Crawford L, Yang KK. Deep self-supervised learning for biosynthetic gene cluster detection and product classification. PLOS Computational Biology. 2023;19(5):e1011162.

- Winchester LM, Harshfield EL, Shi L, et al. Artificial intelligence for biomarker discovery in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2023;19(12):5860-5871.

- Wallstrom G, Anderson KS, LaBaer J. Biomarker discovery for heterogeneous diseases. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(5):747-755.

- López OAM, López AM, Crossa J. Multivariate Statistical Machine Learning Methods for Genomic Prediction. Springer Nature; 2022.

- Obeagu EI, Ezeanya CU, Ogenyi FC, Ifu DD. Big data analytics and machine learning in hematology: Transformative insights, applications and challenges. Medicine (Baltimore). 2025;104(10):e41766.

- Website. doi:10.1016/j.patter.2020.100129

- Website. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3140

- Ou FS, Michiels S, Shyr Y, Adjei AA, Oberg AL. Biomarker Discovery and Validation: Statistical Considerations. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(4):537-545.

- Liang W, Tadesse GA, Ho D, et al. Advances, challenges and opportunities in creating data for trustworthy AI. Nat Mach Intell. 2022;4(8):669-677.

- Harishbhai Tilala M, Kumar Chenchala P, Choppadandi A, et al. Ethical Considerations in the Use of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Health Care: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. 2024;16(6):e62443.

- Center for Drug Evaluation, Research. Qualifying a Biomarker through the Biomarker Qualification Program. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. May 1, 2024. Accessed May 13, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biomarker-qualification-program/qualifying-biomarker-through-biomarker-qualification-program

- Mirakhori F, Niazi SK. Harnessing the AI/ML in Drug and Biological Products Discovery and Development: The Regulatory Perspective. Pharmaceuticals. 2025;18(1):47.

- Constructing bibliometric networks: A comparison between full and fractional counting. Journal of Informetrics. 2016;10(4):1178-1195.

- García-Gutiérrez MS, Navarrete F, Sala F, Gasparyan A, Austrich-Olivares A, Manzanares J. Biomarkers in Psychiatry: Concept, Definition, Types and Relevance to the Clinical Reality. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:432.

- Han Y. Biomarker Analysis in Drug Development: Boosting Precision Medicine. November 11, 2024. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://blog.crownbio.com/biomarker-analysis-drug-development-precision-medicine

- Al-Tashi Q, Saad MB, Muneer A, et al. Machine Learning Models for the Identification of Prognostic and Predictive Cancer Biomarkers: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(9). doi:10.3390/ijms24097781

- Debellotte O, Dookie RL, Rinkoo F, et al. Artificial Intelligence and Early Detection of Breast, Lung, and Colon Cancer: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2025;17(2):e79199.

- Peng J, Jury EC, Dönnes P, Ciurtin C. Machine Learning Techniques for Personalised Medicine Approaches in Immune-Mediated Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: Applications and Challenges. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:720694.

- Ceniceros A, Cuervo L, Méndez C, Salas JA, Olano C, Malmierca MG. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Unraveling the Natural Product Biosynthetic Potential of a Strain Collection Isolated from Leaf-Cutting Ants. Microorganisms. 2021;9(11). doi:10.3390/microorganisms9112225

- Li Y, Wu X, Fang D, Luo Y. Informing immunotherapy with multi-omics driven machine learning. NPJ Digit Med. 2024;7(1):67.

- Xavier JB, Young VB, Skufca J, et al. The Cancer Microbiome: Distinguishing Direct and Indirect Effects Requires a Systemic View. Trends Cancer Res. 2020;6(3):192-204.

- Lydon EC, Henao R, Burke TW, et al. Validation of a host response test to distinguish bacterial and viral respiratory infection. EBioMedicine. 2019;48:453-461.

- Aljameel SS, Khan IU, Aslam N, Aljabri M, Alsulmi ES. Machine Learning-Based Model to Predict the Disease Severity and Outcome in COVID-19 Patients. Scientific Programming. 2021;2021(1):5587188.

- Tang N, Yuan M, Chen Z, et al. Machine Learning Prediction Model of Tuberculosis Incidence Based on Meteorological Factors and Air Pollutants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5). doi:10.3390/ijerph20053910

- Sui J, Jiang R, Bustillo J, Calhoun V. Neuroimaging-based Individualized Prediction of Cognition and Behavior for Mental Disorders and Health: Methods and Promises. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;88(11):818-828.

- Ricka N, Pellegrin G, Fompeyrine DA, Lahutte B, Geoffroy PA. Predictive biosignature of major depressive disorder derived from physiological measurements of outpatients using machine learning. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1):1-13.

- Gashkarimov VR, Sultanova RI, Efremov IS, Asadullin AR. Machine learning techniques in diagnostics and prediction of the clinical features of schizophrenia: a narrative review. Consort Psychiatr. 2023;4(3):43-53.

- Zaslavsky ME, Craig E, Michuda JK, et al. Disease diagnostics using machine learning of B cell and T cell receptor sequences. Science. 2025;387(6736):eadp2407.

- Hubbard EL, Bachali P, Kingsmore KM, et al. Analysis of transcriptomic features reveals molecular endotypes of SLE with clinical implications. Genome Medicine. 2023;15(1):1-23.

- Yang X, Kui L, Tang M, et al. High-Throughput Transcriptome Profiling in Drug and Biomarker Discovery. Front Genet. 2020;11:505377.

- Echle A, Rindtorff NT, Brinker TJ, Luedde T, Pearson AT, Kather JN. Deep learning in cancer pathology: a new generation of clinical biomarkers. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(4):686-696.

- Taheriyoun AR, Ross A, Safikhani A, Soudbakhsh D, Rahnavard A. Longitudinal Omics Data Analysis: A Review on Models, Algorithms, and Tools. Published online June 11, 2025. Accessed June 17, 2025. http://arxiv.org/abs/2506.11161

- Yu Z, Peng W, Li F, et al. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics to reveal biomarkers and mitochondrial metabolic dysregulation of premature ovarian insufficiency. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1280248.

- Chen JW, Dhahbi J. Lung adenocarcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma cancer classification, biomarker identification, and gene expression analysis using overlapping feature selection methods. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13323.

- Kim SY, Jacob L, Speed TP. Combining calls from multiple somatic mutation-callers. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15(1):1-8.

- Nicora G, Zucca S, Limongelli I, Bellazzi R, Magni P. A machine learning approach based on ACMG/AMP guidelines for genomic variant classification and prioritization. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):2517.

- Karar ME, El-Fishawy N, Radad M. Automated classification of urine biomarkers to diagnose pancreatic cancer using 1-D convolutional neural networks. J Biol Eng. 2023;17(1):28.

- Li Y, Sun T, Chen J, et al. Metabolomics profile and machine learning prediction of treatment responses in immune thrombocytopenia: A prospective cohort study. Br J Haematol. 2024;204(6):2405-2417.

- Lee AM, Hu J, Xu Y, et al. Using Machine Learning to Identify Metabolomic Signatures of Pediatric Chronic Kidney Disease Etiology. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33(2):375-386.

- Li YY, Qian FC, Zhang GR, et al. FunlncModel: integrating multi-omic features from upstream and downstream regulatory networks into a machine learning framework to identify functional lncRNAs. Brief Bioinform. 2024;26(1). doi:10.1093/bib/bbae623

- Zhang Y, Yan C, Yang Z, Zhou M, Sun J. Multi-Omics Deep-Learning Prediction of Homologous Recombination Deficiency-Like Phenotype Improved Risk Stratification and Guided Therapeutic Decisions in Gynecological Cancers. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2025;29(3):1861-1871.

- Machine learning algorithms and biomarkers identification for pancreatic cancer diagnosis using multi-omics data integration. Pathology – Research and Practice. 2024;263:155602.

- Ewels PA, Peltzer A, Fillinger S, et al. The nf-core framework for community-curated bioinformatics pipelines. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(3):276-278.

- Mölder F, Jablonski KP, Letcher B, et al. Sustainable data analysis with Snakemake. F1000Research. 2021;10(33):33.

- Terra. Terra. December 12, 2023. Accessed June 16, 2025. https://terra.bio/

- Getting Started — Luigi 3.6.0 documentation. Accessed June 16, 2025. https://luigi.readthedocs.io/en/stable/

- AWS HealthOmics. Amazon Web Services, Inc. Accessed June 16, 2025. https://aws.amazon.com/healthomics/

- GitHub – openwdl/wdl: Specification for the Workflow Description Language (WDL). GitHub. Accessed June 16, 2025. https://github.com/openwdl/wdl

- Partek Flow software. Accessed June 16, 2025. https://www.illumina.com/content/illumina-marketing/en/products/by-type/informatics-products/partek-flow.html

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297-1303.

- Lin YL, Chang PC, Hsu C, et al. Comparison of GATK and DeepVariant by trio sequencing. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1809.

- Medema MH, Kottmann R, Yilmaz P, et al. Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster. Nature Chemical Biology. 2015;11(9):625-631.

- Hannigan GD, Prihoda D, Palicka A, et al. A deep learning genome-mining strategy for biosynthetic gene cluster prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(18):e110.

- Liu M, Li Y, Li H. Deep Learning to Predict the Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Bacterial Genomes. J Mol Biol. 2022;434(15):167597.

- Kawano T, Shiraishi T, Kuzuyama T, Umemura M. A novel transformer-based platform for the prediction and design of biosynthetic gene clusters for (un)natural products. bioRxiv. Published online June 4, 2025:2025.06.02.657346. doi:10.1101/2025.06.02.657346

- Zdouc MM, Blin K, Louwen NLL, et al. MIBiG 4.0: advancing biosynthetic gene cluster curation through global collaboration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53(D1):D678-D690.

- Lai Q, Yao S, Zha Y, et al. Deciphering the biosynthetic potential of microbial genomes using a BGC language processing neural network model. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53(7). doi:10.1093/nar/gkaf305

- Du Z, Zhong N, Li J. Enhancing gene cluster identification and classification in bacterial genomes through synonym replacement and deep learning. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM). IEEE; 2024:19-24.

- Zhou Z, Riley R, Kautsar S, et al. GenomeOcean: An Efficient Genome Foundation Model Trained on Large-Scale Metagenomic Assemblies. bioRxiv. Published online February 5, 2025:2025.01.30.635558. doi:10.1101/2025.01.30.635558

- Xu T, Yang Y, Zhu R, et al. DeepSeMS: a large language model reveals hidden biosynthetic potential of the global ocean microbiome. bioRxiv. Published online March 3, 2025:2025.03.02.641084. doi:10.1101/2025.03.02.641084

- Kautsar SA, Blin K, Shaw S, et al. MIBiG 2.0: a repository for biosynthetic gene clusters of known function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;48(D1):D454-D458.

- Lundberg S, Lee SI. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Published online May 22, 2017. Accessed June 5, 2025. http://arxiv.org/abs/1705.07874

- Ribeiro MT, Singh S, Guestrin C. “Why Should I Trust You?”: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. Published online February 16, 2016. Accessed June 5, 2025. http://arxiv.org/abs/1602.04938

- Huang K, Zhang S, Wang H, et al. Biomni: A General-Purpose Biomedical AI Agent. bioRxiv. Published online June 2, 2025. doi:10.1101/2025.05.30.656746

- Kamya P, Ozerov IV, Pun FW, et al. PandaOmics: An AI-Driven Platform for Therapeutic Target and Biomarker Discovery. J Chem Inf Model. 2024;64(10):3961-3969.

- Website. https://chatgpt.com/auth/login?sso

- Anil R, Borgeaud S, Alayrac JB, et al. Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models. Published online December 19, 2023. Accessed July 9, 2025. http://arxiv.org/abs/2312.11805

- Zhang X, Mallick H, Rahnavard A. Meta-analytic microbiome target discovery for immune checkpoint inhibitor response in advanced melanoma. bioRxiv. Published online March 21, 2025:2025.03.21.644637. doi:10.1101/2025.03.21.644637

- Mirza B, Wang W, Wang J, Choi H, Chung NC, Ping P. Machine Learning and Integrative Analysis of Biomedical Big Data. Genes (Basel). 2019;10(2). doi:10.3390/genes10020087

- Jiao L, Wang Y, Liu X, et al. Causal inference meets deep learning: A comprehensive survey. Research (Wash DC). 2024;7:0467.

- A biomarker identification model from protein protein interaction network using natural language processing and graph convolutional network. Procedia Computer Science. 2024;246:1548-1557.

- Grover A, Leskovec J. node2vec: Scalable Feature Learning for Networks. Published online July 3, 2016. Accessed June 16, 2025. http://arxiv.org/abs/1607.00653

- Digital Twins: State of the art theory and practice, challenges, and open research questions. Journal of Industrial Information Integration. 2022;30:100383.