Improving Patient Adherence in Rehabilitation Using SCT

A Sport Medicine Clinician’s Guide to Improving Patient Adherence through Tenets of Social Cognitive Theory

Kelsey J. Picha , PhD, ATC ¹, Justin S. DiSanti, PhD ², Timothy Uhl, PhD, PT, ATC, FNATA ³

¹ A.T. Still University, Arizona School of Health Sciences, Mesa, AZ, USA

² Duquesne University, Rangos School of Health Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

³ University of Kentucky, Department of Physical Therapy, Lexington, KY, USA

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 August 2025

CITATION: Di Santi., 2025. A Sport Medicine Clinician’s Guide to Improving Patient Adherence through Tenets of Social Cognitive Theory. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6846

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6846

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Patient adherence to rehabilitation, whether following an injury or surgery, is crucial for successful clinical outcomes; unfortunately, adherence is often low. Theory-based interventions have been studied to improve the adherence problem, indicating that a more intentional, theoretically-grounded, practical approach may enhance clinicians abilities to promote their patients holistic well-being. Among the theories applicable to rehabilitation, Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) has demonstrated success in increasing patient adherence to rehabilitation a variable critical to achieving successful rehabilitation outcomes and maintaining the patient’s overall health. Conceptually nested within SCT, two key frameworks that have been used to influence adherence are A) Triadic Reciprocal Determinism, and B) Self-Efficacy. The purpose of this paper is to review literature related to SCT and these two frameworks to detail their importance in promoting adherence, with an emphasis on practical, theoretically-based strategies. Thus, findings were compiled to create a guide for sports medicine clinicians to incorporate SCT into their practice. Through applying this guidance, improved patient self-efficacy and adherence to rehabilitation can be feasibly accomplished by sports medicine clinicians in an intentional, evidence-based approach (e.g., through goal setting, use of positive role models, avoiding empty praise, and enhancing social support.)

Keywords

Social Cognitive Theory, Self-Efficacy, Adherence, Rehabilitation

Introduction

Athletic participation and exercise play a prominent role in the scope of contemporary public health. For instance, nearly eight million high school students participate in sports every year. Despite the multitude of benefits stemming from sports participation, there is inevitably the risk of sustaining an injury. Unfortunately, among the seven million high school participants, approximately two million sport-related injuries occur annually during athletic practice or competition. With the inevitable presence of injuries, sports medicine clinicians are tasked with aiding these athletes as they navigate the recovery and return-to-play processes.

Effective recovery from all types of injuries is critical. However, this may be more important and challenging for severe injuries, those that result in 21 or more days lost of participation and may require surgery. Following an injury or surgical procedure, the standard of care includes prescribed rehabilitation activities, which help regain range of motion, strength, and overall function. Rehabilitation following injury has consistently been reported as beneficial in decreasing pain levels, increasing physical ability, and improving health-related quality of life. Even though rehabilitation is associated with improved outcomes, adherence to rehabilitation in all populations is low. Studies indicate patients are non-adherent to rehabilitation regimens 30-70% of the time. All too frequently, athletes only seek help when they are in pain, but then rarely adhere to the rehabilitation prescribed to them once the pain has subsided. A study by Clement et al. found that athletic trainers identified a lack of adherence as one of the top three unsuccessful coping responses among athletes following an athletic injury. This lack of adherence included athletes not attending their rehabilitation sessions, completing exercises, or following activity modifications. Poor rehabilitation adherence not only threatens athletes outcomes in terms of their physical recovery from injury, but also may hinder their feelings of psychological readiness-to-return and strain their well-being throughout the recovery process.

Recognizing and understanding the barriers to rehabilitation adherence is crucial to improving patient outcomes following an injury or surgery. Among these barriers identified through research are: anxiety, depression, low social support, helplessness, forgetfulness, impatience, lack of time, lack of knowledge, lack of positive feedback, pain with exercise, and low self-efficacy. Although some of these barriers are outside a clinician’s scope of influence, others fall within their area of care and should inspire sports medicine clinicians to individualize patient care further and enhance their adherence to rehabilitation to improve patient outcomes.

Among the known barriers to rehabilitation adherence, self-efficacy meaning one’s belief in their capability to succeed in a specific task stands out as a variable that clinicians can positively influence. Interventions derived from Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) have demonstrated promising results in increasing exercise self-efficacy and have been found to increase exercise adherence. This underscores the potential impact of self-efficacy on rehabilitation adherence and guides clinicians in their interventions. Connections have been established between psychological factors, adherence, and functional outcomes, indicating the importance of their inclusion in the rehabilitation process. Targeting a patient’s self-efficacy and facilitating self-motivation enhances adherence to rehabilitation. To effectively incorporate these concepts into rehabilitation, a fundamental understanding of the theories that support them is essential. Recently, Albert Bandura’s SCT has gained popularity in the rehabilitation realm. Researchers have utilized SCT to explain and improve patient behavior throughout the rehabilitation process. The purpose of this paper is to review SCT with an emphasis on the promotion of self-efficacy to suggest theoretically-based techniques that sports medicine clinicians can incorporate into their clinical practice to improve a patient’s rehabilitation adherence.

Overview of Social Cognitive Theory

HISTORY OF SOCIAL COGNITIVE THEORY

Derived from Miller and Dollard’s 1941 Social Learning Theory, SCT incorporates the importance of observational learning and vicarious reinforcement in human growth. In 1986, Albert Bandura differentiated SCT from Social Learning Theory by emphasizing that cognition is crucial for human functioning, specifically in one’s capability to self-regulate, take action, and comprehend reality. Social Cognitive Theory offers a more comprehensive understanding of how social experiences influence learning capabilities. Within the framework of SCT, individuals are viewed as capable of contributing to their circumstances, rather than being bystanders to their surroundings and environmental influences.

TRIADIC RECIPROCAL DETERMINISM

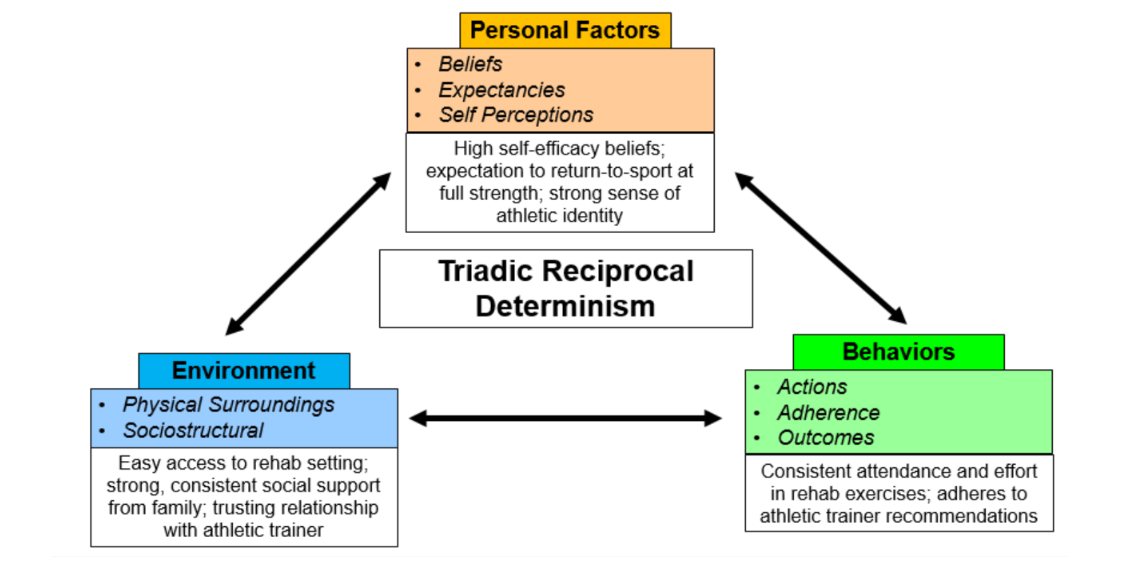

Triadic reciprocal determinism, the foundation of SCT, is the dynamic process by which personal factors (such as cognition, affect, and biological events), behavior (one’s actions), and the environment (physical and social) influence one another. When one of these factors changes, the others will be influenced.

For example, an athlete may be highly motivated to recover fully so that they can be cleared for return-to-play in time for the start of their athletic season (personal factor), and the athletic training facility or sports medicine clinic where they complete their rehabilitation is clean, orderly, and in a location easily accessible to them (environment). The combination of positive personal and environmental factors influences this patient’s actions (behaviors) during recovery, such as their rehabilitation adherence, which in turn influences their belief that they will be successful as they return to sport (another personal factor). However, what happens in this scenario if this same highly motivated athlete lacks access to a facility with appropriate equipment and medical guidance (physical environment) or receives low-quality social support from their clinician (social environment)? Based on the model of triadic reciprocal determinism, the athlete’s rehabilitation adherence (behaviors) and expectations for a successful return (personal factor) would likely suffer. Sports medicine clinicians’ understanding of these interworking factors may translate to enhanced patient action and motivation.

SELF-EFFICACY AND ITS SOURCES

According to Albert Bandura, self-efficacy is the foundation of human agency, and is defined as the belief in one’s capability to complete a certain task. These beliefs play an important role in shaping the way individuals behave and are motivated. Efficacy beliefs can be self-hindering or enhancing based on the positive or negative influential thoughts of the patient. Examining a patient’s self-efficacy beliefs can be a helpful strategy in determining why a patient is not returning for subsequent rehabilitation sessions, especially as research has determined low self-efficacy to be a barrier to rehabilitation adherence. The level of self-efficacy a patient possesses will be indicative of the amount of effort put forth to complete a task and the degree to which it will be sustained. Enhancing a patient’s self-efficacy beliefs can help them to be comfortable and confident, even as they face challenges and push themselves throughout their recovery. If our patients have low self-efficacy for exercise during rehabilitation, they may avoid rehabilitation altogether. Those with a high sense of self-efficacy will approach difficult tasks differently than those with lower self-efficacy. The higher the sense of self-efficacy, the more likely the task will be seen as a challenge to be mastered and not a potential failure to be avoided. Those with higher self-efficacy also tend to set challenging goals and overcome setbacks or failures more quickly, while those with low self-efficacy tend to walk away from difficult tasks, give up easily, fail to set goals, and dwell on deficiencies. These maladaptive rehabilitation behaviors also increase the patient’s likelihood of experiencing emotional distress, such as becoming stressed and depressed. It is also important to note that self-efficacy is both task and situation-specific, which means depending on how similar tasks are, transferability of self-efficacy from domain to domain will vary. For example, if a patient has previously been successful in returning to activity following injury, then they may possess greater self-efficacy when going through a similar process or rehabilitation program later in life. If a patient has not had a successful experience in the past, they may be hesitant or withdrawn from the rehabilitation tasks provided to them by a sports medicine clinician. Self-efficacy is not stagnant; it changes over time, through observation, and with experience. Bandura explains that four sources of self-efficacy contribute to one’s belief in being able to succeed in accomplishing a task: 1) mastery, 2) vicarious experience, 3) verbal persuasion, and 4) physiological or emotional state. Of the four sources, improving self-efficacy through a mastery experience is reported to be most effective. Mastery experiences are built from succeeding or failing during a particular task, such as using two crutches to walk without a limp, then one crutch, and then no crutches. Successful completion of a task can increase one’s perceived capabilities, while a failure may be detrimental to self-efficacy. Thus, ideal rehabilitation tasks should be those that are challenging to the patient, but also within their capabilities to achieve. Social models are a key component of vicarious experience, the second means of strengthening self-efficacy. Observing others succeed or fail during a specific task may either enhance or diminish one’s perception of their own abilities. Models that are perceived to be similar to oneself, such as a teammate with a similar injury, may have a greater impact on self-efficacy than models perceived to be different. Careful consideration of models should be taken into account, as a model could also be detrimental to one’s self-efficacy, such as situations in which the patient’s rehabilitation progress is slower than their model’s. Verbal persuasion, also known as social persuasion, encourages successful task completion. Positive verbal persuasion may increase the effort put forth to complete the task, such as reinforcing the patient’s self-perception that they possess the capabilities to accomplish a specific task. On the contrary, those who are persuaded that they cannot complete a task are more likely to avoid the task or give up quickly when challenges are encountered. Lastly, physiological or emotional states also impact perceived self-efficacy. By altering an individual’s physiological state through reducing stress or negative emotions, their self-efficacy for exercise during rehabilitation can be increased.

Social Cognitive Theory in Rehabilitation

The tenets of SCT have been incorporated to improve outcomes in several patient populations including patients with heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and to a lesser extent, those with musculoskeletal injury. Many of these studies integrated one or more of the tenets of SCT or sources of self-efficacy into their intervention. A systematic review of interventions to increase exercise self-efficacy in patients with heart failure found that the most frequently employed strategies included patient education, self-monitoring, motivational interviewing, self-management, feedback, problem-solving, and goal setting. These interventions were then categorized by the source of self-efficacy used. Mastery experience, learning by doing, was found to effectively increase self-efficacy in patients who were unable to complete high-intensity exercises due to a medical limitation. By simply participating in the practice of exercise, self-efficacy for exercise will increase. This approach can be applied in a sports medicine setting by having a patient complete an exercise without a load first to ensure proper performance and form to build self-efficacy for that exercise during rehabilitation. Vicarious experience through a successful model has implications for positive influence on others’ self-efficacy. Role modeling through team exercise or directly from a clinician increased self-efficacy by integrating social comparison, exchange, and learning. An sports medicine clinician may also create self-referenced vicarious experiences for the patient by emphasizing the transferability between the rehabilitation exercises they perform and those skills required in their sport (e.g., having the patient dribble a basketball while performing squats during their rehabilitation session). Additionally, feedback (verbal persuasion) about exercise from a clinician or motivational interviewing (e.g., What can I do to help you feel energized during our rehabilitation exercises?) has also been found to be successful mechanisms to improve patient self-efficacy for exercise. Lastly, patient education and recognition of physiological responses were identified as another method to increase their self-efficacy through understanding their physiological state. Pain neuroscience education, for example, is a method that has been found to reduce pain and psychosocial factors, increase patient knowledge, function, and movement. When patients have an understanding of their body’s natural responses to injury they may be more likely to persist during rehabilitation. Much of the current literature within the musculoskeletal domain examines patients with low back pain and evaluates self-efficacy as a secondary outcome measure or as a mediator of function. Improvements in pain self-efficacy were identified as better mediators of pain and function than fear of movement in those with low back pain over time, indicating to clinicians that focusing on improving self-efficacy may be a better use of time than reducing their fear of movement. Research focusing on interventions examined the effectiveness of a stretching program on low back pain and found improvement in both low back pain and self-efficacy for exercise. Goal setting interventions to improve rehabilitation adherence consisted of patient-driven short- and long-term goals, with the assistance of a clinician. These effective interventions focused on improving self-efficacy through the four sources. Successful interventions have consisted of a goal-setting performance profile assessment that the patient and clinician completed together to guide treatment. Other studies have used some form of cognitive-behavioral training, or motivational enhancement therapy in addition to physical therapy to increase patient adherence to exercise. Of the above interventions, those that were successful included cognitive-behavioral therapy when paired with the standard of care and patient goal setting.

MEASUREMENTS AND ASSESSMENT

In order to individualize rehabilitation programs based on self-efficacy for exercise, self-efficacy must be accurately assessed. Assessment can be complicated due to the task-specific nature, as there is no one measure that fits all tasks. Questionnaires that have been used within the rehabilitation and exercise realm to assess self-efficacy include, but are not limited to, the Athletic Injury Self-Efficacy Questionnaire, the Barriers Self-Efficacy Scale, Exercise Cardiac Self-Efficacy, Sports Injury Rehabilitation Beliefs Survey, Self-Efficacy for Exercise, Exercise Self-Efficacy, Self-Efficacy Expectations Scales, Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire and Pain Rehabilitation Expectations Scale. The difficulty with many of these scales is that they have been utilized and validated in only specific patient populations. Administrators of these scales need to understand the reliability, validity, and limitations of their use. Patient-reported self-efficacy measures, such as the examples provided, may enable clinicians to accurately understand the multiple facets of the athletes perceptions of what they can do and what challenges they are facing, thereby improving their rehabilitation adherence. In turn, clinicians can focus their treatment plan on addressing areas of need while also using the patient’s responses to guide conversations and interactions. With these considerations in mind, it is essential to note that assessing a patient’s self-efficacy using one of the above scales throughout their rehabilitation experience can indicate the clinician’s efforts to exemplify a personalized, empathetic approach towards treatment, which can strengthen the clinician-athlete relationship and aid in adherence.

Implementation into Clinical Practice

As SCT has been successfully incorporated into rehabilitation interventions in the past, this guide has been constructed for sports medicine clinicians to incorporate these constructs into practice. Emphasis in the literature has primarily been placed on increasing self-efficacy, as it has been associated with rehabilitation adherence, and can capture other identified barriers to rehabilitation adherence. Working within the framework of triadic reciprocal determinism, this guide can be used as an efficient mechanism to change a patient’s personal factors (self-efficacy beliefs) and influence behaviors (rehabilitation adherence) in a sports rehabilitation environment.

During the initial evaluation of an injured patient, it may be beneficial for the sports medicine clinician to evaluate the patient’s level of self-efficacy for rehabilitation. Evaluation should include a discussion with the patient about the plan of care, as well as the use of a self-efficacy questionnaire to document the evaluation of self-efficacy beliefs. Devising a treatment plan to share with an athlete post-surgery will aid in improving self-efficacy, knowledge, and expectations for the following months of rehabilitation. Educating the patient about their surgery, rehabilitation process, and the importance of adhering to rehabilitation will enable them to make informed decisions throughout the process. During the education session, the sports medicine clinician should observe if the athlete seems hesitant, worried, or conveys a lack of confidence. Inquiring about patient’s previous experiences in rehabilitation can offer insight into successes or failures that may contribute to their current state of self-efficacy. By identifying a patient’s self-efficacy beliefs, a clinician can further individualize the rehabilitation plan. For example, a patient with low self-efficacy may present with a lack of confidence, hesitations with new exercises, refusal to complete exercises prescribed, lack of desire to set or complete goals, may give up quickly, or even display no interest in their recovery or return to sport. If further understanding and evaluation of a patient’s self-efficacy seems warranted, patient-oriented self-efficacy measures, like the Pain Self-Efficacy Scale, can be administered to aid in determining a patient’s level of self-efficacy. Sports medicine clinicians can examine these measures to gain a broad sense of the patient’s self-efficacy as well as their item-specific perceptions. This information can then be integrated into a targeted rehabilitation plan to increase or maintain self-efficacy for rehabilitation exercise, as well as minimizing perceived barriers to rehabilitation adherence.

Suppose an athlete is found to have low levels of self-efficacy based on patient-oriented measures or less formally through the patient’s verbal or behavioral indications (i.e., hesitation with new exercises, refusal to complete exercises prescribed, or giving up easily). In that case, this should serve as a signal to the sports medicine clinician that modifications may be necessary to increase patient self-efficacy. Sports medicine clinicians can use and tailor two tenets of triadic reciprocal determinism (personal and environment) to increase the third tenet, a patient’s behavior regarding adherence to rehabilitation. When individualizing a patient’s rehabilitation program to enhance their self-efficacy, the sports medicine clinician can draw from the four sources of self-efficacy.

MASTERY EXPERIENCE

Mastery experiences are considered the most effective source of increasing self-efficacy. Three easy ways to improve self-efficacy through mastery experiences are to 1) refer back to previous related successes, 2) set short and long-term patient goals, and 3) break down the task to be mastered. Sports medicine clinicians can not only assist with recognizing previous successes similar to the task at hand but also create mastery experiences. If the athlete has previously been injured, reminding them, if true, of their previous success in overcoming an injury will help facilitate increased self-efficacy. Goal setting has been found to be significantly correlated with self-efficacy, self-satisfaction, performance, and overall adherence to prescribed rehabilitation programs. With the specifics of goal-setting interventions, preliminary evidence suggests that interventions that are driven by the patient’s motivations, consistently monitored, and evolving to suit the patient’s most resonant goals across the course of their rehabilitation are likely to enhance and maintain their sense of self-efficacy. Sports medicine clinicians should also incorporate both short and long-term goal setting into all conservative and post-surgical rehabilitation programs. Creation of these goals should involve the patient, be recorded, and use some sort of structure (e.g., SMART Goals [specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely]). Clinicians and patients should reevaluate these goals as needed. Tracking this progress will provide tangible evidence to demonstrate to the athlete that they have progressed since day one. In addition to goal setting, clinicians should recognize when patients are struggling to complete a task. If this occurs, breaking down the task into smaller increments may make it more manageable and increase the likelihood of a mastery experience.

VICARIOUS EXPERIENCE

The second most influential source of self-efficacy is through vicarious experiences. Three ways to improve patient self-efficacy through vicarious experiences are 1) observation of successful models, 2) sharing success stories, and 3) use of imagery. By observing other athletes who have successfully recovered, especially those with similar characteristics to their own (type of injury, primary sport, age and other demographic characteristics), athletes undergoing rehabilitation are more likely to feel self-efficacious. During adolescence, self-efficacy is strongly influenced by peers. Therefore, a successful, positively perceived peer may be most influential when incorporating models into rehabilitation. Clinicians may want to organize rehabilitation times by grouping patients with similar conditions and stages in recovery together, providing them with models who can empathize with their experience. Although these athletes will be working towards a return to play together, the sports medicine clinician should emphasize individualized goals. Sports medicine clinicians can also serve as models for athletes by participating in exercise with them while providing instruction. Being a successful visual aid can be very impactful. Additionally, sports medicine clinicians can share success stories of others similar to their recovering athlete, possibly using an upperclassman that the patient already knows who suffered a similar injury. Imagery is another form of vicarious experience that has been associated with increased self-efficacy during athletic rehabilitation. The mental rehearsal of one’s self-succeeding is thought to increase self-efficacy for rehabilitation. The sports medicine clinician should be specific about what outcomes are being rehearsed this should involve the incorporation of multiple senses, timing of action, and can even include practical cues such as incorporating sport equipment or having the athlete dress for the part (i.e., athletic attire). For example, if a soccer player is having difficulty contracting their quadriceps muscle following ACL reconstruction, the clinician may have the athlete close their eyes to mentally rehearse how the muscle feels when it contracts during a free kick.

VERBAL PERSUASION

The third source of self-efficacy, verbal or social persuasion, comes in various forms. These forms or methods include, but are not limited to, 1) providing feedback, encouragement, and praise, 2) ensuring social support is sufficient, and 3) teaching motivational self-talk. The clinician can provide the athlete with words of encouragement and praise for rehabilitation attendance and performance. When providing feedback, it is not just about the quantity of positive persuasion, but also its quality. Words of encouragement or praise by the sports medicine clinician must also be followed up with corresponding actions for the verbal persuasion to be effective. For example, telling an athlete you are doing great is not enough. The athlete should also have a more tangible marker to hold onto in addition to the verbal persuasion, such as showing them the attainment of a goal, such as increased range of motion or strength. Empty praise is discouraged as it may threaten an individual’s self-efficacy for exercise during rehabilitation. Supervising the athlete while they complete their rehabilitation will also allow for verbal persuasion, such as necessary exercise corrections to form and mechanics, which can in turn assist with improved self-efficacy. Consideration of communication style to match the patient’s preference (e.g., content, timing, and frequency of the messaging) can also enhance the quality of verbal persuasion.

The support provided by sports medicine clinicians should not be understated, as clinician-patient relationships have been shown to significantly influence rehabilitation activities in sports medicine settings. Although athletes value social support from their coaches and teammates, the social support from the sports medicine clinician is even greater when the athlete is recovering. Sports medicine clinicians should also try to keep athletes involved with the team as much as possible. If rehabilitation can be completed on the sidelines with the clinician’s supervision, this will aid in the social support from the team and coaches. A sports medicine clinician may want to be proactive at the beginning of each season and meet with coaches and team captains to promote group rehabilitation early in the season. Having a plan in place for when athletes sustain an injury may be less disruptive to their identity as a team member, potentially minimizing feelings of uncertainty and isolation. Captains should be informed of this potential duty at the beginning of the season, as they are commonly the individuals that a teammate may seek encouragement and support from throughout the rehabilitation process. Including the athlete in the warm-up ensures social support from the team and facilitates the completion of rehabilitation exercises.

Another recently investigated and successful form of verbal persuasion is motivational self-talk. Self-talk has been discovered to increase athletes self-efficacy. Sports medicine clinicians should instruct athletes to use statements of affirmation such as I can do this or I am improving, I will keep going. These statements can enhance the athlete’s perceptions of self-control, positive progress, and motivation. Using verbal persuasion to improve an athlete’s self-efficacy is also a time-effective method to avoid adding additional strain to the clinician’s workload.

PHYSIOLOGICAL STATE

The last source of self-efficacy, physiological state, can also be influenced by the sports medicine clinician through patient education. As previously mentioned, patient education should be continuously addressed throughout the rehabilitation process. Research has found significant improvements in self-efficacy when clinicians incorporate symptom education and recognition, exercise education, and guidance in problem-solving into their practice. Incorporating educational reminders could be warranted and just as important as the initial education session for athletes if pain or inflammation persists or recurs. Knowledge of the healing and rehabilitation process will help athletes to better cope with their physiological states.

Limitations

Social Cognitive Theory is only one piece of the puzzle when seeking to improve an athlete’s adherence to injury rehabilitation, as additional theories incorporate the patient’s self-efficacy and motivation for rehabilitation. Criticisms of SCT include lack of detailed explanation of behavior, with consideration given to environmental factors when explaining human action. Sports medicine clinicians should understand that SCT is one of many rehabilitation theories emphasizing one’s self-efficacy. Additionally, other barriers to adherence need to be considered that may not fit as neatly with the SCT framework (e.g., lack of time or anxiety).

Future Research

Future research should aim to enhance interventions that increase patient self-efficacy in athletic adolescent populations. There is a fair amount of evidence in support of these interventions, but primarily in populations other than adolescent athletes. Validation of assessment measures also needs to be addressed in the adolescent population. Additional information in both areas will be beneficial for clinicians working to improve patient adherence to rehabilitation. Lastly, there is a need to improve dissemination strategies and allocate more time to psychological interventions in clinical training and continuing education programs.

Conclusion

This evidence-based guide applies existing literature that has utilized SCT to positively, and intentionally, impact patient’s rehabilitation adherence. Using two key topics nested within the overarching scope of SCT Triadic Reciprocal Determinism, and sources of self-efficacy sports medicine clinicians can utilize tangible strategies to better enhance their patients experiences. By incorporating the above information and through critically analyzing the interaction between personal, environmental, and behavioral aspects of treatment scenarios, while also appealing to the four primary sources of self-efficacy (i.e., mastery, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, physiological/emotional states), sports medicine clinicians can treat their patients in a more holistic and effective manner.

Improving Self-Efficacy & Rehabilitation Adherence

Overview: Nested within the framework of Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), two key frameworks have been researched and identified to meaningfully impact the patient’s rehabilitation adherence: A) Triadic Reciprocal Determinism; B) Self-Efficacy.

Below, both of these frameworks are detailed to identify questions and examples that may help sports medicine clinicians to apply these concepts within their own clinical practice.

Triadic Reciprocal Determinism: How can we account for the interaction between our patients:

- Personal Factors

- Behaviors

- Environment

Below, several questions and examples are provided to address these three components:

Factor Questions & Example

| Personal | What are the patients attitudes toward their recovery? What motivates your athlete? What are unique elements of their personality, and what strengths and weaknesses do they possess? Ex: An athlete is recovering from an ACL tear and will miss the rest of their season. They have low motivation to engage in their rehabilitation activities since they do not have anything to look forward to, and are feeling challenged due to the disruption of their athletic identity. |

|---|---|

| Behavioral | How do you know if the athlete is adhering to their rehabilitation program? Does the athlete have a clear understanding of their injury? Can you promote the patient’s sense of control by giving them an active role in their recovery? (i.e., agency and self-regulation) Are there any barriers that the athlete is experiencing in their adherence? Ex: Since this athlete is feeling down and unmotivated, they are struggling to pay attention during your rehabilitation sessions. So, they do not really understand what they should be doing when they are completing their home exercise program. |

| Environmental | Are there any unique elements of the patient’s physical environment that may help or hurt their adherence? Are there any unique elements of your specific rehabilitation setting that may influence their experience? What is the patient’s quality of social support? Ex: You work with the team to give the athlete some extra support by asking them to go out to dinner. You also take some time to talk with them throughout your session to better understand their experience and provide support. Lastly, you email them links to videos that show the correct form for their exercises, so that they can be more confident in doing them on their own (i.e., a personal factor). |

Self-Efficacy: What are practical, real reasons that our patient should feel good about their capabilities?

Below, several questions and examples are provided to address these three components:

Source of Self-Efficacy Questions & Examples

| Mastery Experiences | How can you set the right level of challenge for their rehabilitation tasks: Challenging, but within their capabilities? How can you help the patient to see their progress and make meaning of small improvements especially in cases of more lengthy recovery timelines? Can you find ways to show how their rehabilitation activities are building skills that will transfer when they return to their sport? Ex: Building a clear timeline to establish expectations; taking time to celebrate small accomplishments and milestones; giving them a basketball to dribble while performing a jumping exercise to illustrate skill transfer. |

|---|---|

| Vicarious Experiences | Are there previous athletes who have recovered from their injury that can be drawn from as positive examples? Are there opportunities for the patient to directly connect with others who have, or previously had, their injury to share their experience? What models both internal (imagery) and external (success stories and positive examples) can help the athlete to believe they will succeed in their recovery? Ex: Implementing imagery exercises later in their recovery to improve psychologically readiness to return; setting up a peer support for injured athletes on the team; using a before/after video to visually show a patient’s recovery progress. |

| Verbal Persuasion | In what ways do you communicate to the patient to build a shared belief in their recovery? Are you verbally recognizing positive outcomes, as well as the process that is leading to those outcomes? Is there any negative messaging either from extern’s own self-talk that may lower their self-belief? Ex: The athlete can use a personalized self-talk word or phrase (e.g., strong, you got this) to build self-belief; when a patient is struggling in an activity that is meant to stretch their abilities, make sure that they know that and give positive recognition for them giving it their all. |

| Physiological or Emotional State | Is the athlete feeling comfortable and present physically, mentally, and emotionally when they are doing their rehabilitation activities? Are any rehabilitation activities causing them to react negatively? If so, how can you adjust your activities or approach? Are there ways to address the patient’s mental and emotional health throughout the process to ensure that they are both physically, and mentally ready to return? Ex: Discuss potential negative emotions or thoughts that they may experience when they are meeting challenges in their recovery or return to play; use deep breathing, positive self-talk, and other mental skills to create a plan to address these challenges. |

References

- Associations NFoSHS. Data from: NFHS high school athletics participation survey, 2004-2005. NFHS. 2006. Indianapolis, IN.

- Holt NL, Neely KC, Slater LG, et al. A grounded theory of positive youth development through sport based on results from a qualitative meta-study. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. Jan 1 2017;10(1):1-49. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2016.1180704

- Burt CW, Overpeck MD. Emergency visits for sports-related injuries. Ann Emerg Med. Mar 2001;37(3):301-8. doi:10.1067/mem.2001.111707

- 2006-2007 High School Athletic Participation Survey. Accessed 10/3/07. http://www.nfhs.org/core/contentmanager/uploads/2006-07_Participation_Survey.pdf

- Kay TM, Gross A, Goldsmith CH, et al. Exercises for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD004250. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004250.pub4

- Fransen M, McConnell S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Database Syst Rev. 2008;4(CD004376)

- Fuentes J, Armijo Olivo S, Magee D, Gross D. Effects of exercise therapy on endogenous pain-relieving peptides in musculoskeletal pain- a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:365-374.

- Jack K, McLean SM, Moffett JK, Gardiner E. Barriers to treatment adherence in physiotherapy outpatient clinics: a systematic review. Man Ther. Jun 2010;15(3):220-8. doi:10.1016/j.math.2009.12.004

- Sluijs EM, Kok GJ, van der Zee J. Correlates of exercise compliance in physical therapy. Phys Ther. Nov 1993;73(11):771-82; discussion 783-6.

- Kolt GS, McEvoy JF. Adherence to rehabilitation in patients with low back pain. Man Ther. May 2003;8(2):110-6.

- Clement D, Granquist MD, Arvinen-Barrow MM. Psychosocial aspects of athletic injuries as perceived by athletic trainers. J Athl Train. Jul-Aug 2013;48(4):512-21. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-48.3.21

- Truong LK, Mosewich AD, Holt CJ, Le CY, Miciak M, Whittaker JL. Psychological, social and contextual factors across recovery stages following a sport-related knee injury: a scoping review. Br J Sports Med. Feb 14 2020;doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101206

- Sciascia A. Prospective assessment of return to pre-injured levels of activity. Theses and Dissertations– Rehabilitation Sciences. University of Kentucky; 2016. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/rehabsci_etds/34

- Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Thomas S, Duke N, Russo R, Quatman-Yates CC. Patient and Parent Perceptions of Rehabilitation Factors That Influence Outcomes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Clearance to Return to Sport in Adolescents and Young Adults. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. Aug 2019;49(8):576-583. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.8608

- Brewer B, Cornelius A, Van Raalte J, et al. Protection motivation theory and adherence to sport injury rehabilitation revisited. The Sport Psychol. 2003;17:95-103.

- Rajati F, Sadeghi M, Feizi A, Sharifirad G, Hasandokht T, Mostafavi F. Self-efficacy strategies to improve exercise in patients with heart failure: A systematic review. ARYA Atheroscler. Nov 2014;10(6):319-33.

- Evans L, Hardy L. Injury rehabilitation: a goal-setting intervention study. Res Q Exerc Sport. Sep 2002;73(3):310-9. doi:10.1080/02701367.2002.10609025

- Coppack RJ, Kristensen J, Karageorghis CI. Use of a goal setting intervention to increase adherence to low back pain rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. Nov 2012;26(11):1032-42. doi:10.1177/0269215512436613

- Millen JA, Bray SR. Promoting self-efficacy and outcome expectations to enable adherence to resistance training after cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiovasc Nurs. Jul-Aug 2009;24(4):316-27. doi:10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181a0d256

- Mendonza M, Patel H, Bassett S. Influences of psychological factors and rehabilitation adherence on the outcome post anterior cruciate ligament injury/surgical reconstruction. NZ J of Physio. 2007;35(2):62-71.