Insights on SIDS in Twins: Immunopathology and Vaccines

Insights from twin Sudden Infant Death Syndrome studies could reveal an aetiopathogenetic pathway to sudden infant death through immunopathology

Paul N. Goldwater

Adelaide Medical School, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, Adelaide University, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED:31 July 2025

CITATION:Goldwater, PN., 2025. Insights from twin Sudden Infant Death Syndrome studies could reveal an aetiopathogenetic pathway to sudden infant death through immunopathology. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(7). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6787

COPYRIGHT© 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI:https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6787

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Twins represent an interesting and unique resource to help unravel the mystery of sudden Infant death syndrome (SIDS). This is because of some outstanding coincidental findings: these include the increased susceptibility to both SIDS and infectious diseases. Susceptibility resides in their inadequate, immature immune system and contributing factors associated with prematurity, such as not benefiting from the protective advantages of transplacental maternal antibodies and not usually receiving the protection of colostrum and/or breast milk. The review examines infection and pseudo-infection (i.e., vaccination) in the context of a disadvantaged, immature infant immune system and how this could contribute as a cause of SIDS through the effects of immune perturbation via hyperimmunization. In this respect, the potential adverse effects of exposure to multitudinous vaccine target antigens in the first year of life is reviewed.

Keywords: SIDS; twins; infection; pseudo-infection; vaccines; Th1 response; Th2 response; mucosal immunity; immunopathology.

THE EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF MEDICINE

Medical Research Archives, Volume 13 Issue 7

REVIEW ARTICLE

Introduction

A detailed search of the literature using PubMed, Google Scholar and Open Evidence was conducted with the aim to retrieve details on the relationship between twins and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), and twins and infection(s), and twins and the effects of vaccinations. The information obtained was analysed and used to develop a cohesive basis for a persuasive argument to acknowledge the importance of the immature immune system in its role in the pathogenesis of SIDS. The review then explains in a logical sequence the supporting information for this idea.

Background

It was shown that approximately 3% of cases of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) are twins. By contrast, twins account for approximately 1.6% of all live births globally. This estimate is based on recent large-scale analyses, which report a global twinning rate of about 12 twin deliveries per 1,000 deliveries (1.2%), but since most twin deliveries result in two live births, twins represent about 1.6% of all live births worldwide.

Twins are at approximately two-fold higher individual risk of SIDS compared to singletons. Malloy and Freeman successfully matched co-twins of 272,029 twin pregnancies and of these found 767 of which one or both had died of SIDS. There were seven cases of both twins dying. The relative risk of this occurrence was 8.17. It has long been thought that the increased risk of SIDS in twins is largely due to factors such as prematurity and low birth weight, these being more common with twin pregnancies. Little thought and little mention by mainstream SIDS researchers has been applied to other, related but potentially more important factors: these pertain to infection and immunity to infectious diseases and/or responses to pseudo-infections, i.e. immunisations and possible immunopathological reactions to immunisation or combinations of these occurrences. These have recently been discussed in detail.

Previously, in an attempt to define the role of the immune system and inflammation in SIDS, this was reviewed from the point of view of the role of the gut microbiota in immunity of the human infant. The review covered a broad range of topics including the role of the gut microbiome in relation to the developmentally critical period in which most SIDS cases occur; the mechanisms by which the gut microbiome might induce inflammation resulting in transit of bacteria from the lumen into the bloodstream; and assessment of the clinical, physiological, pathological, and microbiological evidence for bacteraemia leading to the final events in SIDS pathogenesis.

More recently Ferrante et al. indicated an encouraging change of mainstream thinking: they explored the role of immune protein patterns in cases of SIDS, and added to findings from a previous proteomic study to determine if an unbalanced immune response contributes to the occurrence of SIDS. The authors found there was a downregulation in the proteins Retinoic Acid-Inducible Gene I (DDX58/RIG-I), Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase Adaptor Protein 1(PIK3AP1), Interferon Regulatory Factor 9 (IRF9), Tripartite Motif Containing 5 (TRIM5), TRAF Family Member-Associated Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-Κb) Activator (TANK) and TNF Receptor Associated Factor 2 (TRAF2), and upregulation of CXADR Ig-like cell adhesion molecule (CXADR). The findings supported the role of immune system dysregulation as a potential predisposing factor for SIDS. Both the above-mentioned studies underscore the importance of the immune response in infancy. It is obvious that how an infant responds to infection and pseudo-infection (vaccines) is fundamental to its survival. Clearly more work is required to understand the genetics involved in responses to infection and vaccines. Indeed, twins are a useful means to help gain insight into these effects. The work of Newport et al. has provided a bridge to understanding and is best summarised by quoting that a number of immune responses to vaccines are genetically regulated. These studies have been conducted in different age groups and populations and with a number of different vaccines. In addition to the traditional use of twins to simply demonstrate heritability, twins may also be used for genetic linkage studies aimed at identifying specific genes involved. Indeed, this approach offers many advantages over traditional sibling pair study designs. Once immune response gene loci have been mapped, further studies in larger populations can be undertaken to identify the DNA sequence variants that have a functional effect. In addition to the impact on vaccine development, genes controlling immune responses are likely to be involved in the regulation of discrete phenotypes, such as susceptibility to infectious and autoimmune diseases, which are major causes of mortality worldwide.

Table 1. Risk factors for SIDS that parallel risk factors for susceptibility and/or relationship to infection and/or responses to infections

| Risk Factor | Description/Details |

|---|---|

| Genetics | Genetic predisposition (intrinsic) factors |

| Gender | Possible X-linked genetic mutations/copy number variations, etc. |

| Genetic control | Innate and adaptive immunity, inflammatory response, nitric oxide synthetase 1 (NOS1), brainstem function, metabolic pathways (flavin-monooxygenase 3, enzyme metabolising nicotine), cardiac function |

| Ethnicity | Extrinsic factors |

| Demographic factors | Low socioeconomic status |

| High birth order/previous live births | |

| Prenatal risks | Inadequate/Poor prenatal care |

| Maternal smoking/nicotine use | |

| Maternal misuse of drugs | Heroin, cocaine and other drugs |

| Subsequent births less than 1-year apart | |

| Maternal genitourinary infection | |

| Maternal Alcohol use | |

| Mother being overweight | |

| Teen pregnancy | |

| Higher risk of unsafe sleeping environment | |

| Maternal anaemia | (independent risk factor) |

| Post-natal risk | |

| Seasonality | |

| Viral respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms in days before death | |

| Prematurity | Increases risk of SIDS death by about four times |

| Low birth weight | |

| Exposure to tobacco smoke | Immune suppression, enhancement of bacterial adherence and toxigenicity |

| Prone sleep position | Lying on the abdomen |

| Sleeping prone with Staphylococcus. aureus | |

| Not breastfeeding | |

| Room temperature | Elevated or reduced room temperature |

| Excess bedding, clothing, soft sleep surface and stuffed animals | |

| Co-sleeping | Bed-sharing with parents or siblings |

| Sofa-sleeping | |

| Sleeping on a used mattress | |

| Sleeping in parental bed | |

| Infant’s age | Incidence rises from zero at birth, highest from 2 to 4 months, declines towards zero at 1 year; peak SIDS coincides with nadir of maternally transferred antibodies |

| Probable anaemia | Haemoglobin cannot be measured postmortem |

| Early cord clamping | Causing anaemia or iron deficiency, obviates placental transfer of stem cells, immune cells and immunoglobulins |

| Recent visit to general practitioner or outpatient clinic | |

| No or late Immunisations | |

| Day care attendance | |

| Night-time death | |

| Air pollution |

The earliest epidemiological studies of cot death, now defined as SIDS, clearly indicated that infection, mostly respiratory viral, was associated with these deaths. Despite this knowledge, mainstream SIDS researchers have disregarded this clue and have pursued other avenues to explore the cause of this enigmatic and tragic condition. There has been a preference to be led into focussing on a purported sleep-related problem with attention paid to homeostatic failure involving the heart and/or respiration and/or arousal, centring on the triple risk hypothesis. This has been upheld as the centre piece for research usefulness. Notably, and unaccountably, this approach has little, if any, congruence with the listed infection-related epidemiologically proven SIDS risk factors. All of these have been discussed in detail in previous publications by the author and by others. Therefore, this paper discusses a novel approach by examining SIDS in twins wherein the risk of SIDS and infection is unusually and perpetually high. The paper therefore examines why twins are at increased risk of SIDS and explores in detail the underlying reasons for this increased susceptibility.

Discussion

Twins have a higher risk of dying from infection compared to singletons. Epidemiological studies show that overall mortality of twins is increased. This increased infection-related mortality features mainly during the neonatal period and infancy. A sub-Saharan African pooled study found that twins have a threefold higher under-age 5 mortality rate in twins compared to singletons, with most of these deaths due to infection; this excess mortality also persists when adjusted for birthweight and other risk factors.

In developed high-income countries, twins are at increased risk for neonatal morbidity, including sepsis, compared to singletons, especially in late preterm babies (34-36 weeks gestation). Large population-based studies from the USA and Brazil similarly show that twins have higher odds of experiencing infection-related complications and the requirement for antibiotic treatment in the neonatal period. Moreover, this risk remains after adjusting for gestational age and other confounders.

The twinning rate seems to have increased over the last 30 years. This is likely to be due to the increase in in vitro fertilisation and embryo implantation. The increased rate in twin deliveries coincides with an increase in SIDS in the USA. Based on national vital statistics, and following years of relative stability, the twin birth rate began climbing in the United States in the early 1980s and rose 79% from 1980 to 2014. In 1980, one in every 53 births was a twin. By 2014 it had risen to one in 29 births. Because twins are at greater risk than singletons for poor outcomes, tracking the twin birth rate, along with preterm twin births and neonatal twin morbidity and mortality is important. The report by Martin & Osterman (2019) presented trends in twin childbearing overall for 1980-2018, and by maternal age, race and Hispanic origin, and state of residence for 2014-2018. The twin birth rate declined by an average of 1% a year from 2014 (33.9) through 2018 (32.6) for a total decrease of 4%.

This decline in twin birth rates in the United States from 2014 to 2018 was attributed to the reduction in the use of fertility and in vitro fertilisation treatments that increase the likelihood of multiple gestations.

On the other hand, returning to the issue of why twins are at increased risk, the literature assumes this is primarily mediated by the higher rates of preterm birth and low birth weight among twins, both of which are strong risk factors for infection-related mortality including SIDS. The infection-related factors, it will be shown, have important subtle but potentially lethal effects, discussed later in this paper.

From Lisonkova et al., using modelling to compare mortality rates in the years 1995-6 with the years 2004-5, it was shown singletons underwent a larger relative decline in SIDS than twins (rate ratio 0.67 vs 0.75), whereas in absolute terms twins showed a larger reduction than singletons (rate difference 3.61 versus 2.54). Reductions in SIDS rates were larger at preterm gestation compared with term gestation for both the ratio and the difference measure. Under the fetuses-at-risk approach, temporal changes were larger at full-term gestation among both singletons and twins irrespective of the effect measure used (whether ratio or difference). These differences highlight the need for further research into the underlying mechanisms.

The American Academy of Pediatrics attributes this decline primarily to changes in infant sleep practices rather than to trends in respiratory infections or twinning rates. By contrast, twinning rates increased steadily from 1990 to 2010, rising from 23.1 per 1,000 live births in 1991 to 33.2 per 1,000 in 2009, largely due to increased maternal age and use of assisted reproductive technologies.

So, with considerable data supporting the role of respiratory viral infection as a key player in the SIDS story, the observed declines of SIDS in both singletons and twins during the abovementioned periods is not surprising. On this basis I would contend that the influence of infection is inseparably associated with SIDS. Moreover, the observed pattern of congruent declines in both SIDS and respiratory viral infections provides an alternative and cogent explanation for the observed declines.

Related explanations for the so-called prone sleep effect also have legitimacy through exposure to bacterially contaminated bedding (the parental or co-sleeping bed, sofa) which provides a source of bacteria and thence their toxins, which are found in up to 94% of cases. The Tasmanian SIDS study clearly demonstrated that babies displaying features of infection had a 10-fold increased risk of SIDS, whereas there was no increased risk if there was no associated infection. The Nordic SIDS Epidemiological study demonstrated a 29-fold increased risk of SIDS with prone sleeping with infection.

Difficulties in determining correlations arise with matched case-control studies of respiratory viral infection in living babies showing rates of infection that parallel those of SIDS. These obviously reflect the epidemiology of the time of the studies. These studies, reviewed by Prandota et al. have attempted to demonstrate a link between respiratory infection and SIDS. Naturally and expectedly these and other studies were unable to show a difference in viral infection and lung pathology between SIDS and controls. However, the study by Bajanowski et al. favoured the idea that respiratory viral infection could act as a trigger in SIDS. Despite the positive findings of Bajanowski et al. most mainstream researchers unaccountably continue to tend to discount the possible role of such infection in SIDS. Regrettably, this attitude continues to the present day, despite the established and numerous infection-related epidemiological features as shown above.

The above information clearly shows that twins have a greater susceptibility to SIDS than singletons and that the role played by infection in SIDS pathogenesis is an important one. There remains the question of whether pseudo-infection (i.e. immunisation) is a contributing factor to SIDS causation and whether twins are at increased risk from immunisation than singletons. There is now reasonable evidence that immunisation (vaccination) is a contributing factor in SIDS mortality. Most of this evidence comes from analyses of data from vaccine adverse events registries (VAERs) and recently reviewed by the author and colleagues and the recent publication by Hooker and Miller. The analyses by Goldman and Miller provided data (acknowledging the inherent methodological problems) that supported a relationship between immunisations and mortality and by inference (based on the fact that up to 51% of all the VAERs mortality report cases were diagnosed as SIDS, while the latter paper by Hooker and Miller provides convincing evidence for direct effects of immunisation resulting in several adverse outcomes including neurodevelopmental problems, asthma and ear infections. These all could reflect perturbations of the gut-brain immunity system, autoimmunity or impaired immunity respectively.

Twins and immunisation – adverse effects:

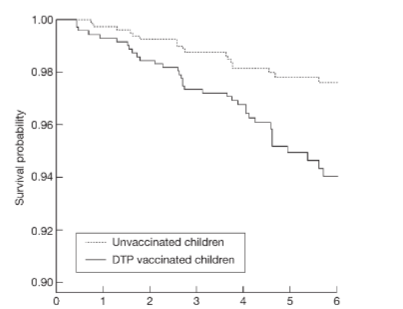

There is a paucity of literature providing direct evidence to show that twins have a higher incidence of post-vaccination-associated deaths compared to singletons, however, one study conducted in Guinea-Bissau and Senegal provided interesting findings suggesting a problem with Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis (DTP) vaccine: the authors identified 626 female male twin pairs born between 1978 and 2000. No sex difference in mortality for boys and girls was found in the pre-vaccination era. In the combined analysis of all studies, the female male mortality ratio (MR) was 0.25 (95% CI: 0.05, 0.93) for pairs having received Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) as the last vaccine, 7.33 (95% CI: 2.20, 38.3) for pairs having received diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTP) as the last vaccine, and 0.40 (95% CI: 0.04, 2.44) for pairs having received measles vaccine as the last vaccine. The female male MR varied significantly for BCG compared with DTP (exact test of homogeneity, P < 0.001) and for DTP compared with measles vaccine (exact test of homogeneity, P < 0.001). These results suggested a mortality-related problem exists with the DTP vaccine. A later study conducted by the same group examined immunisation effects during 1984-1987, children (not specifically twins) who received DTP at 2-8 months of age had higher mortality over the next 6 months, the mortality rate ratio (MR) being 1.92 (95% CI: 1.04, 3.52) compared with DTP-unvaccinated children, adjusted for age, sex, season, period, BCG, and region. The mortality ratio was 1.81 (95% CI: 0.95, 3.45) for the first dose of DTP and 4.36 (95% CI: 1.28, 14.9) for the second and third dose. BCG was associated with slightly lower mortality (MR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.30, 1.33), the mortality ratio for DTP and BCG was significantly inversed. The authors concluded that for low-income countries with high mortality, DTP as the last vaccine received may be associated with slightly increased mortality. Further, since the pattern was inversed for BCG, the effect was concluded to be unlikely to be due to higher-risk children having received vaccination. Rightly, the authors called for clarification of the role of DTP in high mortality areas.

Evidence that twins are at increased risk from immunisation (as they are from infection and risk of mortality) is found in a considerable number of papers reporting SIDS in twins that have happened within a short period post-vaccination. For example, Werne and Garrow (1946) described monozygotic twins dying 24h post diphtheria/pertussis vaccine. The authors attributed the deaths to anaphylaxis based on the finding of an eosinophilic inflammatory response on histopathology. Such a finding we know now can happen as an aberrant eosinophilic polymorph reaction to infection especially respiratory viral infection including Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV). Further, the 24h delay in onset mitigates against true anaphylaxis. Roberts (1987) described twins dying 3h post DPT vaccine. Balci et al (2007) described twins simultaneously dying 2d post DPT, hep B, oral polio vaccines; Mitchell et al (2010) reported twins dying 5d post OPV, DTaP and HibHepB; Huang et al (2013) reported twins dying 10d post DTP OPV given at 60 days of age.

Ladlam et al 2001, reported the case of simultaneous sudden infant death syndrome (SSIDS) in dizygotic twins who were 2-month-old black fraternal girls from Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Both were found dead in their crib at the same time in the prone position. Their mother smoked throughout and after the pregnancy. She had experienced genitourinary infections. At 2 months of age they received their first immunisations and died 18 days afterwards. An in-depth death scene investigation, police investigation, toxicologic analysis, and complete autopsies failed to reveal a specific cause of death and were deemed cases of simultaneous sudden infant death syndrome (SSIDS). The authors did not comment on the recent immunisations.

These same authors went on to investigate simultaneous occurrences of SIDS (SSIDS) and undertook a worldwide search of the medical literature and identified forty-one (41) pairs of twins who had died of SSIDS. For most of these cases there was insufficient information available from which to glean clues to causation, except for cases 25, 29, 34 and 41 of the series. Quoting the Case 25: In early 1973, severe toxemia with high blood pressure developed in a 22-year-old mother 3 weeks before her due date. She delivered identical white male twins by cesarean section. The first twin was discharged 10 days after birth. However, mild jaundice developed in the second twin, and he was hospitalized for 3 weeks. At 4 months of age, the twins received their diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (DPT) immunizations. Shortly before death, they had colds, which resolved. During this time, the twins continued to feed well. The twins were last fed p.m. They were placed to sleep on their sides, more on the abdomen than on the back. The infants slept in new cots with foam mattresses, cotton sheets, and new pure wool blankets. One infant slept on a rubber pillow, and the other one slept on a foam crumb pillow. The second twin was seen alive at 5:00 a.m. by the mother. At 9:30 the next morning, the first twin was found black and cold, prone under the covers. The second twin was also unresponsive but still warm to the touch and nonidentical white twins were born full term and delivered by caesarean section. At 6 weeks of age, they received a routine checkup and their immunization shots. In the early morning of April 11, 1980, the 2.5-month-old twins were fed a bottle of formula and rice cereal. The infants appeared alert and normal. At 5:15 a.m. the twins were found dead in their crib, positioned on their sides, back to back, covered by white blankets. The report twin boys who died simultaneously 2 to 3 hours after receiving DPT immunization. However, the original article failed to provide information on the risk factors, vaccination/immunisation did not feature.

While twins are at higher risk for overall infant and childhood mortality compared to singletons, this excess risk has been largely attributed to perinatal complications, prematurity, and low birth weight by mainstream researchers.

As mentioned, there is a paucity of twin versus singleton studies that have examined vaccination as an independent risk factor. Available studies on twins and vaccination primarily address immune response variability, adverse events, and non-specific effects of vaccines. The study of Jacobsen et al 2007 reviewed 29 specific vaccine studies of twin human subjects but did not discuss vaccine-related mortality. In the study by Aaby et al. which examined DTP vaccination in male-female twin pairs, they found an increased mortality in twins who had received DTP as the last vaccine received compared to unvaccinated twins. They also found females were at higher risk than males. Interestingly, females are also at increased risk from pertussis infection than males, with pertussis incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) being generally higher in female children compared to males, particularly in children under one year of age.

Miller (2021) raises an important piece of information concerning a polyvalent vaccine containing six separate targets and is quoted here: manufacturer, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), produced a confidential report on SIDS. (The report was made publicly available by the Italian Court.) Sudden deaths that occurred within 20 days after hexavalent vaccination were tabulated. The manufacturer concluded that the number of sudden deaths reported after receipt of its hexavalent vaccine did not exceed the background incidence or expected number of cases. However, despite the manufacturer’s conclusion that its hexavalent vaccine does not increase the risk of sudden death, Table 36 on page 249 of the confidential report shows that 62.7% of these deaths clustered within 3 days post-vaccination and 89.6% occurred within 7 days post-vaccination. Perhaps more significantly, 97% (65 of the 67 reported infant deaths) occurred in the first 10 days post-vaccination while just 3% (2 of the 67 deaths) occurred after that.

From the review of Pertussis vaccines and SIDS evidence concerning pertussis vaccines and deaths (classified as SIDS) it was concluded the evidence did not indicate a causal relationship between DPT vaccine and SIDS, and that the studies showing a temporal relation between these events were consistent with the expected occurrence of SIDS over the age range in which DPT immunization typically occurs. There remain serious considerations: these pertain to the inadequate power of the studies to detect significant differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated babies, and, none of the studies have examined the co-occurrence of vaccination and infection. Moreover, it is not too implausible to consider vaccination to be a form of pseudo-infection, and that multiple vaccinations at one time represent numerous coincidental infections. It is also of interest in this regard to know that dual or three respiratory viruses have been found in individual cases of SIDS also accompanied by toxigenic bacterial infection. This is a situation analogous to multiple pseudo-infections (i.e. vaccinations). This brings us to the important question contained within the phenomenon of hyperimmunization. Is there evidence that multiple coincidental vaccinations (i.e. hyperimmunization) could adversely affect a genetically predisposed infant whose immune system is developmentally immature?

Hyperimmunization

The potential role of hyperimmunization as one possible cause of SIDS was recently proposed by the author and colleagues in which we indicated that parenteral (systemic) adjuvant-based hyperimmunization would drive the immune system to an ineffective Th2 skewed response. Such hyperimmunization risks generating downstream complications for each individual subject in its own genetically determined unique way.

Among the problems associated with hyperimmunization is immunotoxicity. This includes autoimmune reactions which may induce or exacerbate preexisting autoimmune conditions and may occur through overstimulation of the immune system, leading to the breakdown of self-tolerance and the generation of autoantibodies. Other immunotoxicities involve systemic inflammatory responses associated with high levels of inflammatory cytokines and immune complexes. Previously we also showed that chronic hyperstimulation (hyperimmunization) paradoxically can result in immunosuppression and in infants may lead to immune tolerance and hypo-responsiveness which is now the focus of current investigation. One obvious result of immunosuppression is inability to overcome infection resulting in unexpected mortality. When given to an immature host, repeated vaccinations with the same or different antigens may result in immune tolerance or hypo-responsiveness. This is possibly partly due to the immature neonatal immune system favouring a Th2-type response and an insufficient Th1-type response upon parenteral immunization. Poor antibody responses are often observed in newborns and neonates.

The work of Goldman and Miller has provided support for the hyperimmunization effect though increasing numbers of injected vaccines correlating with infant mortality. The recent study by Jablonowski et al evaluated 1,542,076 vaccine combinations administered to infants <1 year-old. The study showed that each additional vaccine more than doubled the diseases diagnosed (these were neurodevelopmental, respiratory, or suspected infectious disease). An exponential trend was observed with each additional vaccine given, doubling or more than doubling the average number of diseases diagnosed.

The benefits of immunization are not contested. The value of vaccinations is immeasurable. However, it is now becoming clearer that for a small minority of vaccinees, especially those in infancy who are genetically disadvantaged and react poorly and possibly die. This extremely undesirable outcome was explained on the basis that giving vaccines parenterally to infants whose immature immune system reacts in harmful ways occurs through the Th2 type response. Such a response induces complement-binding IgG and risks immune complex formation and other adverse outcomes. It has been argued that the current Childhood Immunization Schedule is fundamentally flawed because it aims to provide circulating antibodies for pathogens that do not usually enter the bloodstream (e.g. SARS-Cov-2 and other respiratory viruses including influenza, B. pertussis, C. diphtheriae). The mode of infection of these pathogens is via the respiratory mucosa. Best prevention of these infections is provided by extremely avid mucosal secretory IgA. This should indicate that properly assessed vaccines would be best applied to the mucosal surface to stimulate Th1 responses which include cell-mediated immunity (T-cell memory). IgA is not produced in parenterally administered vaccination which induces a Th2 immune response. On the other hand, infections causing viraemia, including polioviruses, hepatitis B, morbillivirus (measles), Thorubulavirus (mumps virus), rubivirus (rubella) virus, Haemophilus influenzae b (Hib), pneumococcus, meningococcus cause disease through transmucosal entry of the pathogen or its toxin into the bloodstream and therefore are neutralised by IgG antibodies induced by parenteral immunization. Interestingly parenteral vaccination against polioviruses does not prevent infection. The vaccine produces circulating antibodies that neutralise virus entering the bloodstream from the site of infection in the gut thence preventing the virus from reaching the central nervous system. Nevertheless, a mucosa-directed vaccine stimulating a Th1 response could provide protection via IgA and IgG via development of CMI memory.

An important part of successful immunisation concerns the vaccine dose wherein the lowest effective dose provides best protection. This has been discussed recently. It is not widely appreciated that the current infant immunisation schedule can subject a baby to up to 69 separate (with repeats) systemically injected vaccine antigen targets within the first year of life. This is because of polyvalent vaccines. The total number (69) is derived from the Australian Childhood Immunisation Schedule: (Table 2) (HB =1 (at birth), hexavalent [Infanrix hexa / Vaxelis: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, HB, polio, Hib) = 6 x 3 = 18, MMR =1 x 3 = 3, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (3 x 13 = 39), influenza (1 x 4 = 4), meningococcal (1 x 4 = 4).

Table 2: Australian Childhood Immunization Schedule (birth to 12 months)

| Age | Vaccine |

|---|---|

| Birth | Hepatitis B (usually offered in hospital) |

| 2 months (can be given from 6 weeks of age) | Diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, hepatitis B, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), Rotavirus, Pneumococcal, Meningococcal B Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children |

| 4 months | Diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, hepatitis B, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), Rotavirus, Pneumococcal, Meningococcal B Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children |

| 6 months | Diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, hepatitis B, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), Pneumococcal Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in WA, NT, SA and Qld |

| 6 months to under 5 years | Influenza (annually) |

| 12 months | Meningococcal ACWY, Measles, mumps, rubella, Pneumococcal, Meningococcal B Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children |

Limitations

It is acknowledged that the argument used in this review is dependent on information derived from a diverse range of sources including case reports spanning many decades, studies based on indirect information including vaccine adverse event register data requiring care in interpretation, other studies from countries in which infant mortality is unusually high, and other more dependable case-control epidemiological studies. However, the principles of modern immunology are incontrovertible and provide a solid basis for the arguments put forward.

Conclusion

Twins represent a unique position in helping to understand SIDS pathogenesis and this review has provided access to a store of valuable insights into this by examining the occurrence of SIDS and infection and pseudo-infection (vaccination) in twins. Meanwhile, the debate continues over the question of multiple vaccines and the potential for idiosyncratic adverse events. The recent call out for developments in SARS-Cov-2 vaccination seems to have overlooked the key principles of modern immunology which centres on the benefits of Th1 responses and avoidance of the downsides of Th2 systemic parenteral immunisation. The so-called evidence-based systemic (Th2) immunisation approach seems destined for failure, including a continuation of doubtful and evanescent IgG-based “protection”. Rigorous randomised, placebo-controlled trials of appropriately targeted vaccines that stimulate Th1 responses (mucosal-applied for mucosal-transmitted infections, and with limited use, where feasible, of Th2 acting parenteral vaccines at lowest possible dose) are required to address the problem and to provide parents with clear information on risks and benefits. Given the information discussed above, special attention should be paid to twins (and multiples) considering their apparent increased vulnerability to some parenterally administered vaccines. Considering the review overall together with the notable list of infection-related SIDS risk factors, and applying these to infant care in general, it is not unreasonable to employ the principles of basic hygiene, and to pay special attention to infections and to consider delaying vaccination when the two coincide and to encourage breastfeeding whenever possible.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

No interests to declare.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

None.

Corrigendum

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in the Context of the Future of Vaccination, and the Question of Systemic or Mucosal Immunity Med Res Arch 2025;13(6)

Goldwater PN, Gorczynski RM, Lyndley RA, Steele EJ. We wish to draw to the attention of our readers of the above paper a citation omission. Regrettably, in this Medical Research Archives paper we have unintentionally failed to cite an important and highly relevant paper which is an in-depth review of mucosal immunity. Prof Robert Clancy’s paper was not included, as the primary focus was on immunisation and sudden infant death syndrome. We apologise for this oversight. We hope this corrigendum will remind readers to reading our paper.

1. Clancy R. The Common Mucosal System Fifty Years on: From Cell Traffic in the Rabbit to Immune Resilience to SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Shifting Risk within Normal and Disease Populations. Vaccines 2023;11:1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11071251.

2. Goldwater PN, Gorczynski RM, Lindley RA, Steele EJ. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in the Context of the Future of Vaccination, and the Question of Systemic or Mucosal Immunity. Med Res Arch 2025;13:(in press).

References:

- Monden C, Pison G, Smits J. Twin Peaks: More Twinning in Humans Than Ever Before. Human Reproduction. 2021;36(6):1666-1673. doi:10.1093/humrep/deab029.

- Platt MJ, Pharoah PO. The Epidemiology of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:27-9. doi:10.1136/adc.88.1.27.

- Getahun D, Demissie K, Lu SE, Rhoads GG. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Among Twin Births: United States, 1995-1998. J Perinatol 2004;24:544-51. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211140.

- Pharoah PO, Platt MJ. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in Twins and Singletons. Twin Res Human Genetics. 2007;10:644-8. doi:10.1375/twin.10.4.644.

- Lisonkova S, Hutcheon JA, Joseph KS. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: A Re-Examination of Temporal Trends. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:59-68. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-59.

- Malloy MH, Freeman DH. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome among Twins. Arch Pediatr Adolescent Med 1999;156:736-740.

- Goldwater PN, Gorczynski RM, Steele EJ. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: A Review and Reevaluation of Vaccination Risks. Med Res Arch [online] 2025;13(3). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i3.6349.

- Goldwater PN, Gorczynski RM, Lindley RA, Steele EJ. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in the Context of the Future of Vaccination, and the Question of Systemic or Mucosal Immunity. Med Res Arch 2025;13:(in press).

- Goldwater PN. Gut microbiota and immunity: possible role in sudden infant death syndrome. Front Immunol 2015; 6:2015. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00269.

- Ferrante L, Opdal SH, Byard RW. Recently Further Exploration of the Influence of Immune Proteins in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) Acta Paediatrica. First published: 23 June 2025. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.70197.

- Newport MJ, Goetghebuer T, Marchant A. Hunting for immune response regulatory genes: vaccination studies in infant twins. Expert Rev Vaccines 2005;4:739-746, DOI: 10.1586/14760584.4.5.739.

- Courts C, Madea B. Genetics of the sudden infant death syndrome. Forens Sci Int 2010;203:25-33.

- Opdal SH, Rognum TO. Gene variants predisposing to SIDS: current knowledge. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2011;7:26-36.

- Blair PS, Sidebotham P, Berry PJ, et al. Major epidemiological changes in sudden infant death syndrome: a 20-year population-based study in the UK. Lancet 2006;367:314-19.

- Hoffman HJ, Damus K, Hillman L, et al. Risk factors for SIDS. Results of The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development SIDS Cooperative Epidemiological Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1988;533:13-30.

- Howard J. Hoffman HJ, Hunter JC, Damus K, Pakter J, Peterson DR, Gerald van Belle G, Eileen G. Hasselmeyer EG. Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis Immunization and Sudden Infant Death: Results of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Cooperative Epidemiological Study of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Risk Factors. Pediatrics 1987;79:598-611. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.79.4.598.

- Moon RY, Carlin RF, Hand I; TASK FORCE ON SUDDEN INFANT DEATH SYNDROME and THE COMMITTEE ON FETUS AND NEWBORN. Evidence Base for 2022 Updated Recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment to Reduce the Risk of Sleep-Related Infant Deaths. Pediatrics 2022;150:e2022057991. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057991. PMID: 35921639.

- Stockwell EG, Swanson DA, Wicks JW. Economic status differences in infant mortality by cause of death. Public Health Rep 1988;103:135-42.

- Highet AR, Goldwater PN. Maternal and perinatal risk factors for SIDS: a novel analysis utilizing pregnancy outcome data. Europ J Paediatr 2013;172:369-72.

- Mitchell EA, Taylor BJ, Ford RPK, et al. Four modifiable and other major risk factors for cot death: The New Zealand study. J Paediatr Child Health 1992;28: S3-8.

- Rintahaka PJ, Hirvonen J. The epidemiology of sudden infant death syndrome in Finland in 1969-1980. Forens Sci Intl 1986;30:219-33.

- Ostfeld BM, Schwartz-Soicher O, Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Hegyi T. Prematurity and Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths in the United States. Pediatrics 2017;140:e20163334. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3334.

- Van Nguyen JM, Abenhaim HA. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: Review for the Obstetric Care Provider. Am J Perinatol 2013;30:703-14. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1331035.

- Oltman SP, Rogers EE, Baer RJ, et al. Early Newborn Metabolic Patterning and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. JAMA Pediatrics 2024;178:1183-1191. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.3033.

- Makarious L, Teng A, Oei JL.SIDS Is Associated With Prenatal Drug Use: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of 4,238,685 Infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2022;107:617-623. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2021-323260.

- Friedmann I, Dahdouh EM, Kugler P, Mimran G, Balayla J. Maternal and Obstetrical Predictors of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). J Matern-Fetal Neonat Med 2017;30:2315-2323. doi:10.1080/14767058.2016.1247265.

- Highet, A.R., Goldwater, P.N. Maternal and perinatal risk factors for SIDS: a novel analysis utilizing pregnancy outcome data. Eur J Pediatr 2013;172:369-372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-012-1896-0.

- O’Leary CM, Jacoby PJ, Bartu A, D’Antoine H, Bower C. Maternal Alcohol Use and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Infant Mortality Excluding SIDS. Pediatrics 2013;131:e770-8. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1907.

- Tanner D, Ramirez JM, Weeks WB, Lavista Ferres JM, Mitchell EA. Maternal Obesity and Risk of Sudden Unexpected Infant Death. JAMA Pediatrics 2024;178:906-913. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.2455.

- Klonoff-Cohen HS, Srinivasan IP, Edelstein SL. Prenatal and Intrapartum Events and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2002;16:82-89. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3016.2002.00395.x.

- Getahun D, Amre D, Rhoads GG, Demissie K. Maternal and Obstetric Risk Factors for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:646-52. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000117081.50852.04.

- Osmond C, Murphy M. Seasonality in the sudden infant death syndrome. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1988;2:337-45.

- Pease A, Turner N, Ingram J, et al. Changes in Background Characteristics and Risk Factors Among SIDS Infants in England: Cohort Comparisons From 1993 to 2020. BMJ Open 2023;13:e076751. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-076751.

- Blackwell C, Moscovis S, Hall S, Burns C, Scott RJ. Exploring the Risk Factors for Sudden Infant Deaths and Their Role in Inflammatory Responses to Infection. Front Immunol 2015;6:44-51. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00044.

- Goldwater PN. SIDS, Prone Sleep Position and Infection: An Overlooked Epidemiological Link in Current SIDS Research? Key Evidence for the “Infection Hypothesis”. Med Hypotheses 2020;14:110114. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110114.

- Highet AR, Berry AM, Bettelheim KA, Goldwater PN. Gut microbiome in sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) differs from that in healthy comparison babies and offers an explanation for the risk factor of prone position. Int J Med Microbiol 2014;304:735-41. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.05.007.

- Thompson JMD, Tanabe K, Moon RY, et al. Duration of Breastfeeding and Risk of SIDS: An Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171324. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-1324.

- Hauck FR, Thompson JM, Tanabe KO, Moon RY, Vennemann MM. Breastfeeding and Reduced Risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2011;128:103-10. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3000.

- Moon RY, Carlin RF, Hand I. Sleep-Related Infant Deaths: Updated 2022 Recommendations for Reducing Infant Deaths in the Sleep Environment. Pediatrics 2022;150:e2022057990. doi:10.1542/peds.2022-057990.

- Carlin RF, Moon RY. Risk Factors, Protective Factors, and Current Recommendations to Reduce Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: A Review. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:175-180. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3345.

- Jullien S. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Prevention. BMC Pediatr 2021;21(Suppl 1):320-328. doi:10.1186/s12887-021-02536-z.

- Rechtman LR, Colvin JD, Blair PS, Moon RY. Sofas and infant mortality. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1293-300.

- Tappin D, Brooke H, Ecob R, et al. Used infant mattresses and sudden infant death syndrome in Scotland: case-control study. BMJ 2002;325:1007.

- MacIntyre CR, Leask J. Immunization myths and realities: Responding to arguments against immunization. J Paediatr Child Health 2003;39:487-91.

- Carpenter R, McGarvey C, Mitchell EA, et al. Bed sharing when parents do not smoke: is there a risk of SIDS? An individual level analysis of five major case control studies. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002299.

- Goldwater PN. Current SIDS Research: Time to Resolve Conflicting Research Hypotheses and Collaborate. Pediatr Res 2023;94:1273-1277. doi:10.1038/s41390-023-02611-4.

- Ostfeld BM, Schwartz-Soicher O, Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Hegyi T. Prematurity and Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths in the United States. Pediatrics 2017;140:e20163334. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3334.

- Poets CF, Samuels MP, Wardrop CA, et al. Reduced haemoglobin levels in infants presenting with apparent life-threatening events a retrospective investigation. Acta Paediatr 1992;81:319-21.

- Mascola MA, Porter TF, Chao TT-M. Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping After Birth: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 814. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136:e100-e106. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004167.

- Rabe H, Gyte GM, Díaz-Rossello JL, Duley L. Effect of Timing of Umbilical Cord Clamping and Other Strategies to Influence Placental Transfusion at Preterm Birth on Maternal and Infant Outcomes. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;9:CD003248. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003248.pub4.

- Tarnow-Mordi W, Morris J, Kirby A, et al. Delayed versus Immediate Cord Clamping in Preterm Infants. New Engl J Med 2017;377:2445-2455. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1711281.

- Gomersall J, Berber S, Middleton P, et al. Umbilical Cord Management at Term and Late Preterm Birth: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2021;147:e2020015404. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-015404.

- Hutton EK, Hassan ES. Late vs Early Clamping of the Umbilical Cord in Full-term Neonates: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Controlled Trials. JAMA 2007;297:1241-52. doi:10.1001/jama.297.11.1241.

- Gilbert RE, Fleming PJ, Azaz Y, Rudd PT. Signs of illness preceding sudden unexpected death in infants. BMJ 1990;300:1237-1239.

- MacIntyre CR, Leask J. Immunization myths and realities: Responding to arguments against immunization. J Paediatr Child Health 2003;39:487-91.

- Miller NZ.: Vaccines and sudden infant death: An analysis of the VAERS database 1990-2019 and review of the medical literature. Toxicol Rep 2021;8:1324-1335.