Anemia and Schistosomiasis: Intersecting Health Challenges

Intersecting Layers of Fragility: Anemia and Schistosomiasis

Flávia R. M. Lamarão¹, Jackline P. Ayres-Silva¹

- Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Laboratório de Medicina Experimental e Saúde (LAMES), RJ, Brazil

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 May 2025

CITATION: Lamarão, FRM., and Ayres-Silva, JP., 2025. Intersecting Layers of Fragility: Anemia and Schistosomiasis. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(5).

https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6480

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6480

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Anemia and schistosomiasis are intertwined global health challenges, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations in low-income regions. Anemia, with a global prevalence of 24.3%, affects over 1.92 billion people, particularly women and children under five. Schistosomiasis, a neglected tropical disease, afflicts approximately 250 million individuals, primarily in tropical and subtropical areas. The intersection of these conditions is exacerbated by layers of fragility, including poverty, geographic isolation, and demographic factors such as age and gender. Women, especially those pregnant, and children are particularly vulnerable due to the compounded effects of iron deficiency, parasitic infections, and inadequate access to healthcare. Iron metabolism plays a crucial role in the pathophysiology of anemia in schistosomiasis. The parasite-induced blood loss and iron sequestration in the liver and spleen contribute significantly to blood deficiency. Current treatments, primarily praziquantel, do not address long-term damage or the complex interplay between anemia and parasitic infection, underscoring the need for novel therapeutic strategies targeting iron metabolism and fibrosis. This review highlights the importance of addressing these intersecting higher hierarchical levels and layers of vulnerabilities to molecules, through a multifaceted approach that includes improved diagnostics, comprehensive treatment strategies, and sustained research efforts. Tackling the ecological, social, and medical determinants of these diseases is essential for breaking the cycle of poverty and disease, ultimately improving health outcomes in the most affected and structurally fragile populations.

Keywords

- Anemia

- Schistosomiasis

- Iron deficiency

- Global health

- Vulnerable populations

1. Introduction

Anemia is a worldwide public health problem, with a global prevalence across all ages around 24.3% (95% UI 23.9-24.7), affecting 1.92 billion (95% UI 1.89–1.95) people, being 1.23 billion (95% UI 1.21-1.25) women and 693 million (95% UI 675-712) men in 2021. The prevalence of severe disease was 0.9%, moderate was 9.3% and mild was 14.1%. Females are more prone to develop it, in which 31.2% of women and 38% of pregnant adult females affected. Children are the second most prevalent group, with 41.4% of younger than 5 years old troubled, and still have the highest incidence. The largest causes of anemia in 2021 were dietary iron deficiency, haemoglobinopathies, and neglected tropical diseases. In addition, infectious and inflammatory diseases, and genetic hemoglobin disorders are also common causes.

Anemia can lead to reduced physical work capacity due to impaired tissue oxygen delivery, poor maternal and perinatal health outcomes, such as preterm labor, for pregnant women, and delayed growth, low birth weight, decreased cognitive performance and motor development in newborn and children. Weakness, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, poor work productivity, predispose to infection and heart failure are also reported.

Iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) was estimated to cause 22% (95% uncertainty interval [UI] 8–35) of maternal deaths in 2019, being in the top 3 regional rankings. To worst, neglected tropical diseases such as malaria, schistosomiasis, were related to red blood deficiency which increased in prevalence in the last years.

Schistosomiasis prevalence worldwide is around 251 million people, with more than 700 million in endemic areas, which account around 78 countries, with 90% of them in Africa. Chronic schistosomiasis may affect people’s ability to work, and in some cases can result in death, what is difficult to estimate due to liver and kidney failure, bladder cancer and ectopic pregnancies due to female genital schistosomiasis. In children, schistosomiasis can cause reduced red blood cells and hemoglobin counts, stunting and a reduced ability to learn, which are usually reversible when treated appropriately. Deaths are underestimated and need more attention due to hidden pathologies, missed diagnostic, what result in late diagnosis and treatment, especially in low and low-middle income countries. Besides those, deaths are underestimated in 11,792.

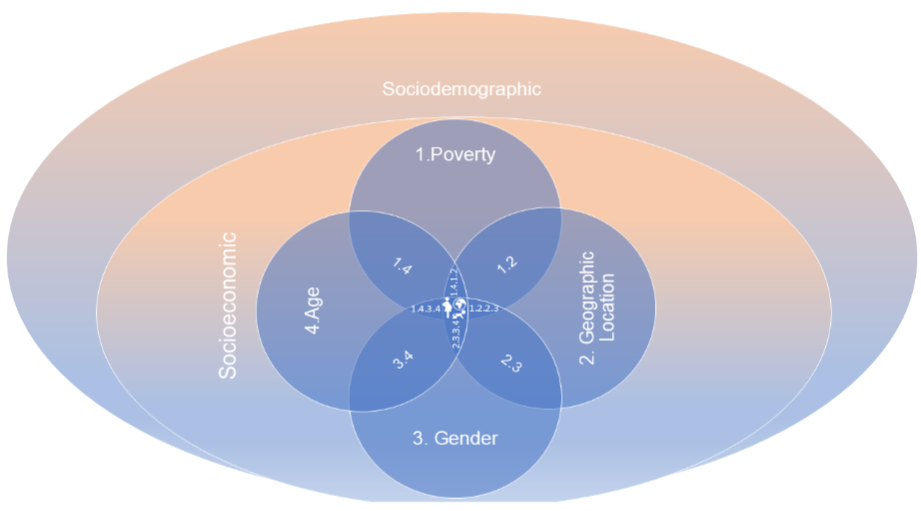

In this review we will discuss the signs and symptoms associated with anemia and schistosomiasis and explore how these two conditions can interact and potentially alter the course of parasitic infections, the perspectives for treatment and discuss various hierarchical levels and layers of fragility common to both Anemia and Schistosomiasis: First and Second Higher Hierarchical Level – Sociodemographic and Socioeconomic Conditions and its layers of Poverty, Geographic Vulnerability; Gender; Age which results in strata of accumulated risk for women, pregnant women and children as the most affected by this intersection.

2. Overview of anemia as a global health issue, including its prevalence and impact including the overlap of parasitic infections.

2.1. ANEMIA

Anemia is a significant global public health issue with a diverse and multifactorial etiology. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, the prevalence was approximately 24.3% worldwide in 2021. Large variations were observed in anemia burden by age, sex, and geography, with children younger than 5 years, women, and countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia being particularly affected. The factors frequently associated with include malnutrition, hemoglobinopathies, hemolytic anemia, and infections. Among neglected tropical diseases, malaria and schistosomiasis are the most prevalent, affecting 9% and 13% of the population, respectively. These infections have shown an increasing trend in recent years, worsening the prognosis.

Anemia is a hematological condition characterized by hemoglobin (Hb) concentrations below specific thresholds: less than 122 g/L for white women, 115 g/L for black women, and less than 110 g/L for children and pregnant women. These levels are subject to fluctuations influenced by demographic factors such as ethnicity, age, and sex. Consequently, there are ongoing proposals to review and adjust these reference ranges to better align with the needs of diverse populations, especially the most affected ones: children, women, particularly pregnant ones, and ethnic differences between black and white people.

Anemia is a complex condition with a multifactorial etiology, with iron deficiency being the most prevalent cause worldwide. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), chronic parasitic infections such as malaria, hookworm infections, schistosomiasis and its intestinal manifestations significantly contribute to iron deficiency and consequent anemia. These infections often lead to chronic blood loss and impaired iron absorption, exacerbating the burden of anemia and is illustrating important intersection layers between infectious disease, nutritional deficiency, and structural vulnerability. The Global Burden of Disease Study indicated a persistent high incidence of anemia, affecting nearly a quarter of the global population, with significant disparities observed across different demographics such as age, sex, and geography. In particular, children under five years of age, women, and populations in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia bear the brunt of this condition. Chronic parasitic infections, especially malaria and schistosomiasis, have been identified as significant contributors to the burden disease in these regions, where they exacerbate iron deficiency due to ongoing blood loss and impaired nutrient absorption. This situation contrasts strongly with that in regions such as Europe, where it frequently occurs independently of iron deficiency, suggesting alternative pathological mechanisms for schistosomiasis.

These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions that address both schistosomiasis and the resultant anemia, integrating disease control with nutritional and medical support to effectively address these intertwined public health challenges.

As upper mentioned, in Europe, where parasitic infections are rare, anemia often occurs without underlying iron deprivation. This discrepancy provides a valuable opportunity to study the relationship between parasitic infections, specifically schistosomiasis, and anemia. Case studies from the old continent highlight instances of this blood disease not attributed to iron deficiency, isolating the variables and highlighting this relationship. These cases are particularly insightful for understanding how parasitic infections such as schistosomiasis can lead to hemoglobin deficiency through iron deprivation independent mechanisms. It emphasizes the importance of considering epidemiological factors when addressing anemia and underline the necessity for tailored and local interventions which reports the specific causes in different regions. It highlights mechanisms that can be studied as separately facts or cumulative ones whenever comorbidity occurs, high probable in specific sociodemographic levels, helping to understand late outcomes and disabilities caused by one, another or concurrent diseases.

2.2. IRON METABOLISM

Iron is stored as ferritin and hemosiderin in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow and participates in several essential functions in organisms at the systemic and cellular levels. Iron is found in hemoglobin and indispensable for the production of red blood cells. Approximately 80% of the available heme iron is used for the synthesis of hemoglobin in maturing erythroblasts. Hemoglobin is formed by two globin chains bound with a heme group which has a central iron. Thus, most of the iron is found in the hemoglobin present in erythroblasts, and a lack of iron affects oxygen transport and compromises energy and muscle metabolism due to the main function of gas transportation.

Normal red blood cells have a lifespan of 120 days when they undergo cellular apoptosis through the recognition of senescent erythrocytes that transition through biochemical changes, with iron being recycled by splenic macrophages in their majority and by the liver in their minority. In this process, iron is absorbed and stored in the form of ferritin or transported by ferroportin or transferrin. This iron recycling process amounts to approximately 20 to 25 mg per day, and the iron absorbed by the duodenum through food amounts to approximately 1 to 2 mg per day. The importance of recycling this trace element is clear, as the daily iron amount needed to meet its demand cannot be supplied only by food intake. In this sense, the body has efficient recovery because any modification in genes that encode iron metabolism-related proteins can generate several forms of anemia, compromising the bone marrow erythropoietic activity.

Ferritin and medullary iron are good indicators of iron reserves, as the iron present in the body can be measured by ferritin concentration since this protein stores approximately 30% of saturated iron. The hemoglobin level is also important for estimating the available functional iron since it participates in red blood cell synthesis. Otherwise, it can be evaluated through the iron transport compartment by quantifying the serum transferrin, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), and transferrin saturation index. It is necessary to carefully evaluate each parameter, as elevated ferritin concentrations may indicate inflammation, infection, liver disease, or risk of iron overload.

Heme and nonheme iron are found in nourishment, the former is present in animal-source food origin, such as beef, fish, beef liver, and chicken heart. Its main characteristic is related to bioavailability, since foods of animal origin have a high absorption rate, approximately 20 to 30%; therefore, it is easily absorbed by the body, and its efficiency is influenced by dietary consumption, such as citrus fruits that are rich in ascorbic acid. The latter is found in plant foods, dairy products, and eggs. The absorption rate of this element is low compared to the previous one, with approximately 2–5% bioavailability. However, foods rich in phytates, polyphenols, tannins, and oxalate show decreased absorption of this mineral in the intestinal tract.

The human body does not have a mechanism to excrete iron, and iron excess can cause oxidative damage to proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids in cells. For this reason, there is an essential mechanism responsible for mineral homeostasis, which occurs at a systemic level by the hormone hepcidin, which is regulated by the HAMP gene in hepatocytes, and the main iron exporter, ferroportin (FPN1), which at the cellular level involves the iron regulatory proteins (IRPs) IRP1 and IRP2. IRPs detect low levels of intracellular iron and bind to iron-responsive elements (IREs), a noncoding region located in the 3′ region of the mRNA of iron transporter proteins. This binding increases the expression of iron transport and storage proteins, such as transferrin, ferritin, and divalent metal transporter (DMT1). Therefore, the absorption of this metal also increased, as positive feedback. However, when intracellular iron levels are high, absorption decreases through another mechanism, as a negative one. This is because Fe-S occupies the active site of IRPs, preventing binding with IREs and decreasing iron absorption.

Intestinal iron absorption can increase or decrease according to an individual’s body requirements and the expression of the proteins involved. First, dietary iron is absorbed by intestinal cells through specific proteins. Initially, ferric oxide (Fe3+) is converted to ferrous oxide (Fe2+) by the brush-border ferrireductase duodenal cytochrome b (DCYTB). Subsequently, iron is absorbed by divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT-1, NRAMP2, SLC11 A2) from the apical membrane of enterocytes and released into the bloodstream by ferroportin. At the systemic level, when the plasma iron reservoir is at normal or higher than expected levels, hepatocytes produce hepcidin, which binds to ferroportin (FPN1), inducing its internalization and destruction. Thus, high iron concentrations increase hepcidin expression and inhibit iron absorption by enterocytes. Therefore, iron remains in enterocytes, reducing the amount of circulating iron in the blood. The opposite also occurs when iron levels are low and hepatocytes decrease the production of hepcidin, which increases iron absorption. The absorbed metal can be stored in the form of ferritin or released into the bloodstream. Ferroportin transports iron from the basement membrane of the intestine to the bloodstream, where it must be converted to Fe3+ for efficient transport by transferrin. DCYTB is also upregulated to increase iron absorption by enterocytes. When ferroportin is destroyed, this transport is affected, and iron absorption decreases. Therefore, at the systemic level, iron control is based on its absorption from macroscopic scenario to genetic expression ability.

Hepcidin is a hormone released into the bloodstream that acts on the ferroportin receptors present in enterocytes, macrophages, and hepatocytes. Its production can be controlled by the hepatic iron reserve, hematopoiesis expansion, a decrease in hepatic oxygenation, and the induction of an inflammatory process. The expression of this hormone increases when an individual is subjected to inflammation or infection. Interleukin-6 is the main cytokine involved in this process, thus inducing an increase in hepcidin, therefore, explains the iron sequestration and low erythropoietic iron reserves. Iron deficiency-induced tissue hypoxia increases the levels of hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF-2-alpha), which inhibits hepcidin synthesis from the expression levels stimulating erythropoietin production. The red cells formed are hypochromic microcytic owing to iron deficiency. This process can happen also in anemia of inflammation which occurs in various manifestations as in chronic and autoimmune diseases, advanced cancer, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease which helps to understand conserved pathways and, also, in schistosomiasis might happen concomitantly with iron deficiency anemia.

Iron depletion occurs when the levels of the iron-storing protein ferritin are low. This indicator is detected in the serum to assess the concentration of iron stored in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. In individuals with iron deficiency, the serum ferritin concentration is lower than 12 µg/L in infants, children, and adolescents and 15 µg/L in adults or elderly individuals according to new WHO guidelines. A lack of iron in the body can cause iron deficiency anemia, resulting in hypochromic microcytic red blood cells in the peripheral blood. Iron deficiency anemia can occur 1) when iron intake is insufficient to meet the demand during the growth or pregnancy period since at that time requirements are increased and consumption must be sufficient to supply it; 2) when iron absorption is inadequate; 3) when there is blood loss from the uterus or digestive tract; 4) when there is renal loss of hemosiderin resulting from chronic intravascular hemolysis; or 5) when there is little accumulation of iron in the lungs and pulmonary bleeding as a result of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis.

Iron deficiency can occur in three stages of disease severity. The first stage is associated with the depletion of iron storage. The second phase correlates with iron deficiency, characterized by defective erythropoiesis in which the marrow has difficulties synthesizing functional compounds due to the lack of iron. Consequently, hemoglobin levels are low, which leads to anemia over time. The third phase is characterized by iron deficiency anemia, which is the most severe, as it is related to morphological changes in hemoglobin due to the depletion of iron stores; it also impacts the genetic expression profile to control iron status.

3. Schistosomiasis as a neglected tropical disease affecting millions in tropical and subtropical areas which outcomes includes anemia of infectious disease and iron deficiency.

3.1. SCHISTOSOMIASIS

Schistosomiasis is a waterborne neglected tropical parasitic disease caused by trematode worms that is prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas and affects almost 250 million people worldwide, with 78 countries with active infection. The transmission of schistosomiasis occurs when the larval forms of the parasite, called cercaria, are released by freshwater snails, especially from the genus Biomphalaria, and the parasites penetrate people’s skin when they use freshwater for playing, drinking, and washing (clothes, dishes, baths). After the cercaria penetrates the human body, its forked tail is shed. The first stage involves the migration of schistosomulae through venous circulation until they develop into adult schistosomes, which live in mesenteric blood vessels from the gut or bladder where females release eggs. Some of the eggs are passed through the bowel/bladder wall and are released from the body in the feces or urine or go to the liver through the bloodstream, where they are imprisoned and form granulomas. Eggs are released in nature and hatch when they are warmed and eclode the miracidia that penetrate snails and restart the cycle over and over again. The six main species infecting humans are Schistosoma mansoni, S. japonicum, S. mekongi, S. guineensis, S. intercalatum and S. haematobium, the first five ones colonize mesenteric vessels, and S. haematobium lives in the bloodstream near the bladder.

3.2. DIAGNOSIS:

Accurate delineation of the prevalence and intensity of schistosomiasis based on definitive documentation is crucial for its elimination, which relies heavily on the availability of sensitive diagnostic methods. Traditionally, the diagnosis of urogenital schistosomiasis has utilized urine filtration and the modified Kato technique for intestinal schistosomiasis. Recent advances have stemmed from two main developments: the widespread implementation of massive drug administration (MDA), resulting in predominantly low-intensity infections, MDA and the introduction of high-definition techniques that measure schistosome circulating cathodic antigens (CCA) and anodic antigens (CAA) in both serum and urine. Transitioning from microscopy to antigen detection offers significant advantages, such as addressing the challenge of detecting egg-negative but worm-positive cases in national control programs, as highlighted by Colley et al. The life cycle of schistosomes, which includes multiplication in snail hosts, allows transmission to continue as long as a small number of individuals excrete eggs. A new high-sensitivity Schistosoma CAA strip test suitable for pooled urine sample testing for area-wide diagnosis has shown promise. This method demonstrated in studies in Lao and Cambodia alongside stool examinations that detecting circulating schistosome antigens is substantially more sensitive than egg detection by approximately eightfold.

On the other hand, the increase in trade and travel between China and Africa has led to cases of schistosomiasis among Chinese travelers returning from Africa. Proposals have been made to develop new non-species-specific screening tools or to adapt existing immunoassays. Research into highly sensitive rapid assays for animal diagnosis, such as colloidal gold immunochromatography and nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, has been progressing. These tests are particularly pertinent in China, where livestock are major transmission vectors. Despite some cross-reactivity with other parasites, such as Hemonchus sp. and Orientobiharzia sp., these assays have proven effective for both wild and domestic animals, which will be crucial following the elimination of the infection from humans.

3.3. TREATMENT:

Praziquantel (PZQ), recognized as the first anthelmintic that satisfies the World Health Organization’s (WHO) criteria, has therapeutic efficacy against various trematode and cestode infections and is the principal treatment for schistosomiasis. This drug, discovered in 1972 and initially developed for veterinary use, became a primary treatment for human schistosomiasis. It is noted for its efficacy and tolerability among those affected, as it significantly reduces both the parasitic burden and the severity of symptoms at an effective dose of 40 mg/kg. Given its critical role in combating this disease, research has been directed toward enhancing certain pharmacological characteristics of PZQ, such as its solubility, and exploring innovative drug delivery systems. These advancements primarily seek to address issues such as parasitic resistance, rapid absorption of the drug into the bloodstream post-administration, and extensive first-pass metabolism.

PZQ is a pyrazine-isoquinoline compound that is insoluble in water but soluble in ethanol, chloroform, and dimethylsulfoxide. It is used against all known schistosomiasis species as well as certain cestodes and trematodes. Initial treatments for schistosomiasis utilized potassium and antimony tartrate, also known as emetic tartrate, beginning in 1918. This was followed by the introduction of sodium and antimony dimercaptosuccinate and sodium and antimony di-(pirocatechol-2,4-disulphonate), commonly referred to as stibophen. Subsequently, various other antimony compounds have been incorporated into clinical practice for treating schistosomiasis, such as sodium antimonylgluconate (Triostib), antimony-bis-pyrocatechn sodium disulfonate (Stibofen), thiomelate sodium antimony (Anthiomaline), and antimony gluconate (Triostan), all of which are administered parenterally. Despite their effectiveness against the major Schistosoma species—S. mansoni, S. hematobium, and S. japonicum—these antimony salts were not used due to severe side effects, including thrombocytopenia and other blood disorders.

Initially, the high cost of PZQ posed a significant barrier to its widespread use. However, a price reduction was achieved in 1983 when the Korean company Shin Poong introduced a new manufacturing process. Today, PZQ is marketed in a racemic form, containing equal mixtures of its two enantiomers; (R)-PZQ is the active anthelmintic agent, while (S)-PZQ is inactive. Commercially, PZQ is available under the brand names Cestox and Cisticid. Resistance caused by PZQ due to persistence of schistosomiasis is a critical point.

3.4. PREVALENCE:

There is great heterogeneity in disease incidence, intensity and morbidity according to geographical location and socioeconomic and environmental factors. Some geographical regions with persistent levels of infection even after MDA remain and are called persistent hotspots, which are hurdles to controlling schistosomiasis. There are four criteria for defining a persistent hotspot according to the WHO: a baseline prevalence ranging from 10% to 5%, at least two rounds of MDA, coverage of 75% of the population and a reduction of at least ⅓ in prevalence after two rounds of MDA.

Schistosomiasis remains a critical public health issue as a neglected tropical disease, affecting approximately 250 million people, primarily in tropical and subtropical regions. This parasitic infection, which is caused by trematode worms and is transmitted through contact with contaminated freshwater, causes significant geographical, socioeconomic, and environmental disparities in terms of prevalence, intensity, and morbidity. Despite efforts such as MDA, certain regions continue to exhibit persistent high levels of infection, identified as persistent hotspots by the WHO criteria. These hot spots pose substantial challenges in schistosomiasis control, emphasizing the need for sustained and targeted public health strategies that address not only the biological aspects of the disease but also the underlying social and environmental factors contributing to its spread and impact, as an important layer. In poorer countries, it is expected that schistosomiasis acts as a pernicious amplifier of anemia risk, not only because of direct health impacts but also because it thrives in conditions of poverty—where access to clean water and healthcare is limited—thereby perpetuating a cycle of disease and deprivation that disproportionately affects the most vulnerable ones (women, pregnant women and children) as an impactful layer, which in difficult to transpose due to the sum of upper mentioned reasons.

3.5. SYMPTOMS AND ASSOCIATED COMORBIDITIES IN THE DISEASE COURSE AND DURING SURVEILLANCE

Schistosomiasis significantly debilitates affected populations, particularly children, leading to malnutrition, stunted growth, and cognitive impairments. Pregnant women suffering from these infections are at risk of premature birth, delivering low birth weight infants, and experiencing heightened maternal morbidity and mortality.

Despite advances in medical treatments and improved access to healthcare, schistosomiasis continues to adversely affect vulnerable populations, with little potential for improvement. As uppermentioned pregnant women and school-aged children who are particularly at risk in developing countries, which presents a sum of layers of negligence. If no intervention occurs, Schistosomes live an average of 3–10 years but, in some cases, as long as 40 years in their human hosts. Adult male and female worms live much of this time in copula, and the slender female fits into the gynecophoric canal of the male, where she produces eggs and he fertilizes them. This is probably the cause of morbidity in these fragile populations, which normally present as cumulative exposure as reduced work capacity, decreased ability to execute activities of daily living, poor pregnancy outcomes and reduced cognitive function.

In adults, intestinal schistosomiasis can cause severe health issues, including periportal fibrosis (PPF). This condition involves extensive macrofibrosis of the liver, detectable by ultrasound, that can block the main portal vein, leading to portal hypertension (PHT), and specially for children, anemia additionally leading to malnutrition, stunted growth, and cognitive impairments might cause long-term morbidity with unknown impact. This condition can result in serious complications such as ascites, collateral blood vessel formation, and ultimately, death. Urogenital schistosomiasis similarly leads to significant pathology in the urinary and genital systems and is a known risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder. In some regions, the inability to effectively manage schistosomiasis results in both continuous high infection rates and widespread morbidity. These persistent “hotspots” underscore the need to reevaluate research on severe morbidity and its underlying mechanisms, particularly as this research has fallen out of favor during periods of preventive chemotherapy (PC) implementation. The focused and spatially structured nature of schistosomiasis epidemiology suggests that interactions between genes and the environment at the host-parasite interface are critical. Schistosomiasis still ranks as the second most critical human parasitic disease in terms of socioeconomic impact, causing significant morbidity and mortality, particularly across the African continent.

The updated WHO NTD Roadmap for 2021–2030 outlined the key strategic interventions for combating schistosomiasis, besides MDA, WASH (WAter, Sanitation and Hygiene) practices, vector control, veterinary public health, and case management. Additional strategies such as behavioral change, self-care, and environmental management are also emphasized as critical components in the fight against this disease.

According to the WHO, as countries approach or interrupt the transmission of the disease, it is essential to establish a surveillance system. This system is necessary to identify and address any resurgence in transmission and to prevent the reintroduction of the disease from areas where it remains endemic.

4. Comprehensive Strategies for Schistosomiasis Control and Elimination: Diagnostic Advances and Global Health Challenges

Schistosomiasis disproportionately affects school-aged children who are particularly vulnerable due to hygiene practices and recreational activities such as swimming or fishing in infested waters. The disease typically spreads through routine agricultural, domestic, occupational, and recreational activities that expose individuals to infested water. In 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted the provision of interventions for neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), including schistosomiasis, reducing treatment coverage. During this year, it was estimated that at least 251.4 million people required preventive treatment for schistosomiasis, but only over 75.3 million people received it. Control efforts for schistosomiasis have traditionally focused on reducing disease morbidity through periodic, large-scale population treatment using PZQ. However, a more comprehensive approach that includes access to potable water, improved sanitation, and snail control could further diminish transmission rates and reduce disease burden.

In this sense, Schistosomiasis was reintroduced as a new global goal for elimination by 2030, and One Health represents a comprehensive strategy that unites the well-being of humans, animals, and the environment, highlighting the importance of collaboration and communication across multiple sectors, disciplines, and regions. Several challenges obstruct the eradication of schistosomiasis, such as a range of animal reservoirs, extensive snail habitats, common flood events, heightened movement of populations, and social demographic status. The WHO has highlighted the necessity of increasing PZQ coverage from 35% to 75% among school-aged children in areas vulnerable to infection.

An effective surveillance system should extend beyond the mere identification, investigation, and disruption of ongoing transmission to include proactive infection prevention. Such a system allows program managers to pinpoint at-risk areas and populations to observe trends in infections among humans and animals, thereby facilitating timely interventions and control measures. For instance, despite the official elimination of human schistosomiasis in Japan in 1996, vigilant monitoring continued due to the persistence of infected intermediate hosts, and detection was performed by three-step examinations, including skin tests, ELISA and fecal examination; however, after 1984, the skin test was eliminated.

The current strategies for schistosomiasis control mainly rely on snail control, drug treatment (such as PZQ), advanced sanitation, and health education. Although the present method for the control of schistosomiasis is largely based on drug treatment, snail control using molluscicides still plays a crucial role, such as metaldehyde and methiocarb, in various forms, including tablets, granules, and liquids, offers a means to combat slug and snail populations. Upon ingestion, metaldehyde baits induce dehydration and death, while methiocarb, a carbamate, targets the central nervous system by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase, leading to the death of the pests.

Long-term, well-structured control programs make a difference. The Japanese control program is proof that not only elimination but also eradication in the country can be achieved by long-term, uninterrupted activities. As made clear by Kajihara and Hirayama, once the epidemiology had been determined, elimination was a straightforward affair with the most recent human infection reported in 1976.

It is a great challenge to control schistosomiasis in low-income countries due to financial burdens and environmental pressures where infections caused by the helminth S. mansoni remains a significant public health issue. Among its clinical manifestations, the hepato-splenic type is notable for periportal fibrosis, which can lead to portal hypertension, liver failure, and death. The potential severity of these conditions underscores the importance of epidemiological studies in endemic areas, as such research can guide targeted interventions. For example, in Brazil, important data were collected in Minas Gerais from 2011 to 2020. A total of 37,535 cases were reported, 159 of which resulted in death (mortality rate of 0.4%). This study highlighted the macroregions of Vale do Aço (n=10,438; 27.8%), Northeast (n=8,327; 22.2%), and Central (n=5,928; 15.7%) and the municipalities of Belo Horizonte (n=3,148; 8.3%), Inhapim (n=2,026; 5.3%), and Ipatinga (n=1,710; 4.5%).

Sociodemographic characteristics were more common among males (n=23,722; 63.2%), individuals in the 25-34 age group (n=7,025; 18.7%), individuals with incomplete primary education (n=5,139; 13.7%), and those with mixed race (n=18,312; 48.8%). Clinically, the hepato-intestinal form was predominant among both males (n=11,676; 49.2%) and females (n=6,914; 50.1%), with an overall prevalence of 49.5% (n=18,591). The hepato-splenic form was more frequent in males (n=524; 2.2%) than in females (n=214; 1.5%). The cure rate was high among both males (n=17,460; 73.6%) and females (n=10,460; 75.8%), with an overall cure rate of 74.4% (n=27,923). Males had a 1.4-fold greater chance of developing the hepato-splenic form (95% CI=1.2-1.6; p<0.0001) and a 1.5-fold greater chance of death from schistosomiasis (95% CI=1.06-2.21; p=0.0198). Temporally, the highest number of notifications was in 2011 (n=11,777; 31.3%), with a significant reduction by 2020 (n=1,050; 2.7%). A similar trend was observed in the incidence rates (IR), with 58 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 2011, decreasing to 5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 2020. There was a correlation between the passage of years and the decrease in IR (r2=0.6392; p=0.0055). Therefore, to maintain a reduction in incidence and prevent lethal outcomes, it is crucial to implement interventions primarily in the highlighted macroregions and among individuals who match the identified profile, such as males, young adults, and those with low educational levels, especially in endemic areas and also map all other regions in Brazil as it was performed in Minas Gerais, as Brasil is a continental country in size and population.

5. Pathophysiological Link between Schistosomiasis and Anemia

Schistosomiasis can cause anemia and iron deficiency in different ways, perhaps exact mechanisms are unclear yet. Understanding the complex relationship between schistosomiasis and hemoglobin deficiency is critical for discovering more effective treatments and improving patient outcomes, especially in low-income countries. Multiple mechanisms are involved in the complex nature of the disease within schistosomiasis, which may result not only in iron deficiency but also in a protective response against iron overload in some cases.

Current drugs for schistosomiasis, while effective in controlling the parasite, do not address long-term organ damage, such as fibrosis, or the complex interplay of factors leading to anemia, which leads to a gap in the development of innovative therapeutic strategies that can reverse pathophysiological damage, particularly fibrosis, and target underlying iron metabolism issues. Further research into these mechanisms is essential to gather treatment and to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with schistosomiasis-induced anemia.

Four potential pathways could underlie the association, as evidenced by studies in both animal and human models: extracorporeal loss of iron, splenomegaly leading to sequestration of red blood cells, autoimmune hemolysis, and anemia caused by chronic inflammation.

In this section, we will focus on extracorporeal loss of iron and how splenomegaly, hemolysis and anemia caused by chronic inflammation are associated with the former.

5.1. EXTRACORPOREAL LOSS OF IRON DUE TO PARASITIC ACTIVITY

The physiological demand for iron fluctuates among children versus adults and men versus women. For example, the normal daily iron loss for men is 1 mg/day, that for women during menstruation is equivalent to 1.5 mg/day, while the maximum absorption does not vary among them, being approximately 1-2 mg/day. For this reason, the daily need for consumption is greater in women, especially when pregnant or breastfeeding. During the entire gestational period, iron demand is greater in the second and third trimesters, as approximately 60–80% of iron absorption in newborns occurs in the third trimester. For this reason, feeding women requires daily nutritional requests and supplements.

In the same way, populations infected with parasites experience daily blood loss due to worm requirements for metabolism or physical adhesion. People in countries with low and middle incomes (LMICs) usually have other infections associated with S. mansoni, which can cause iron loss. Usually, most coinfections occur due to hookworms in the stool and urine and poor WASH habits that promote those coinfections.

For example, patients with heavy infection can lose up to 250 ml, or a quarter of a liter of blood, daily, and up to 29 mg of iron in the gastrointestinal tract, thus leading to direct iron deficiency anemia when radioisotope studies with chromium 51-tagged red blood cells are employed. Blood loss was measured using Cr isotopes in patients with chronic Schistosoma mansoni polyp formation in the colon, and the results showed that these patients lost up to 12.5 ml of blood daily. Using 59Fe isotopes, these workers also measured blood loss in the urine of patients infected with Schistosoma hematobium and demonstrated that these patients can lose up to 120 ml of blood daily. Blood loss in schistosomiasis patients, however, is intermittent and not constant, and although it may be severe for a few days, it usually ceases for prolonged periods. As a result, iron loss can even be severe in chronic hookworm infections.

Many studies have shown correlations between anemia features such as hemoglobin and serum ferritin and blood loss, egg count and coinfections (hookworms and malaria). The results demonstrated conflicting outcomes, with most showing that hemoglobin levels increased after worm treatment and others decreased. However, one study in Cameroon showed no significant difference in hemoglobin levels six months after Schistosoma-targeted therapy in males with moderate or high-intensity S. hematobium infection. Nevertheless, those who received therapy involving hook warmth alone or combined with S. hematombium experienced increased levels of hemoglobin. Similar results were described by the Stephenson group, who observed extremely efficacious treatment against S. hematobium, with a 99% reduction in egg count, when children were treated with drugs targeting Schistosoma, with slight changes in hemoglobin. In contrast, during treatment against hookworms and Schistosoma, the patient’s Hb concentration increased after therapy. Two studies revealed a more pronounced association between hemoglobin concentration and infection with S. japonicum in males than in females. One human study of patients suffering from schistosomiasis and polyposis showed that surgical removal of polyps stopped blood loss despite persistent S. mansoni infections. However, some studies have shown a relationship between egg counts and either hemoglobin or serum ferritin.

5.2. SPLENOMEGALY, HEMOLYSIS AND CHRONIC INFLAMMATION

Factors that disturb hepatic flux, such as portal hypertension caused by granulomas and fibrosis, clamping of the hepatic pedicle and ischemia and reperfusion, seem to cause anemia. Additionally, sequestration of red blood cells in the spleen can lead to this deficiency (and hepatomegaly). In this way, further efforts will be necessary for isolating factors that can cause iron loss to understand the contribution of each element that causes it. In such manner, infections with sterile adult S. mansoni worms, which cannot produce eggs, also cause anemia. Surprisingly, when the hepatic pedicle was clamped, Fe was deposited in the splenic parenchyma. Similarly, one study using ischemia/reperfusion of the liver revealed liver inflammation just 10 min after the procedure. However, when Fe was previously administered to clamping, then preventing injury.

Schistosomiasis, often accompanied by coinfections such as hookworm and malaria, can lead to significant iron loss and subsequent anemia through multiple pathways. While some studies have indicated improved hemoglobin levels following targeted antiparasitic treatments, others have shown diverse outcomes, suggesting that the pathophysiological mechanisms may vary significantly across different population groups and infection intensities. Notably, interventions targeting schistosomiasis alone sometimes have a limited impact on iron deficiency without simultaneous treatment for coinfections. The role of Schistosoma hemozoin in pathogenicity and iron metabolism within the host also highlights the intricate biological interactions at play, which are further complicated by gender-specific iron needs and physiological demands. These findings illustrate the necessity for targeted diagnostic and treatment strategies that consider the multifactorial nature in endemic regions, emphasizing the need for a coordinated approach to tackle both parasitic infections and their broader hematological impacts.

Coinfection with schistosomiasis and hookworms significantly exacerbate blood and iron loss, far exceeding the impact observed with either infection alone. This synergistic effect highlights the critical need for integrated approaches in diagnosis and treatment to address the compounded risks associated with such coinfections. By understanding and mitigating the heightened loss of essential nutrients and increasing morbidity, we can better tailor public health interventions to effectively combat these parasitic diseases.

5.3. ILLUSTRATING THE RELATIONSHIP OF IRON DEFICIENCY WITH SCHISTOSOMIASIS WITHOUT MALNUTRITION

Conversely, reported studies highlight cases where patients, isolated from most external confounding factors—such as iron deficiency anemia due to malnutrition—may serve as strong models for understanding anemia caused by schistosomiasis. A 74-year-old European immigrant man from Uganda presented with acute schistosomiasis (Katayama syndrome), which is most common in nonimmune travelers to endemic areas and is caused by a hypersensitivity reaction to Schistosoma ova. The investigation started in 2015 when the patient presented fatigue and iron deficiency anemia and received two units of packed red blood cells, which were further investigated with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) and colonoscopy, which revealed a 1 cm rectal polyp. This tumor was subsequently identified as a tubular adenoma with low-grade dysplasia and was found to contain several calcified Schistosoma ova consistent with S. mansoni. Oral iron supplementation commenced, but no other treatment was administered. The patient’s medication at that time included 75 mg aspirin once a day, 2.5 mg bisoprolol once a day, 20 mg atorvastatin every night and 7.5 mg ramipril once a day. Iron had been stopped for several months. In December 2017, the patient with progressive worsening fatigue was found to have microcytic anemia. On further questioning in December 2017, the patient could not recall having ever previously been diagnosed with schistosomiasis or being treated or followed up for this infection. The final diagnosis of schistosomiasis has been investigated in recent years.

This report aimed to raise awareness of chronic inflammation anemia and other pathways that schistosomiasis might be involved isolating from most confounding factors such as coinfections, and anemia due to malnutrition that immigrants coming to developed world can be underdiagnosed of Schistosomiasis.

6. Challenges faced: mass drug administration, drug resistance and accessibility of healthcare.

The WHO recommends treating preschool-aged children infected with schistosomiasis based on clinical judgment and incorporating them into large-scale treatment programs using pediatric PZQ formulations. Treatment frequency is linked to the prevalence of infection among school-aged children, with annual treatments often necessary in high-transmission areas for multiple years. Monitoring these interventions is crucial to assess their effectiveness in reducing disease morbidity and transmission, aiming toward eliminating schistosomiasis as a public health concern. Periodic treatment helps alleviate mild symptoms and prevent progression to severe chronic stages of the disease.

However, a significant challenge in controlling schistosomiasis is the limited availability of PZQ, especially for adults. In 2021, only 29.9% of those needing treatment received it globally—a decline of 38% from 2019, largely due to COVID-19 disruptions. Despite these challenges, this medicine remains the recommended treatment for all forms of schistosomiasis due to its efficacy, safety, and affordability. It significantly reduces the risk of severe disease, particularly when treatment begins in childhood, and it is administered repeatedly.

Although PZQ is widely used, it does not provide immunity against future infections, necessitating frequent readministration in regions where the disease is common. Furthermore, the reliance on a monotherapy approach with this drug carries significant risks. There is a danger of developing strains resistant to it, as well as an increased incidence of acute schistosomiasis, a condition for which PZQ offers no efficacy. Acute schistosomiasis typically affects individuals previously unexposed to schistosome antigens, such as travelers to endemic areas, who then contract the infection.

Significant progress in schistosomiasis control has been made over the past 40 years in countries such as Brazil, Cambodia, China, Egypt, Mauritius, and several Middle Eastern nations, achieving widespread national treatment coverage and reducing disease prevalence. Recently, there has been a notable expansion of treatment campaigns in sub-Saharan Africa, resulting in a nearly 60% decrease in schistosomiasis incidence among school-aged children over the last decade. Continued assessment of transmission status remains necessary in various countries to maintain and enhance control efforts.

However, the emergence of drug resistance and other limitations of PZQ have spurred a critical demand for the development of alternative treatments. Currently, the pipeline for new antischistosomal drugs is sparse, and no promising candidates are available on the market. This lack of advancement is partly due to the insufficient funding allocated to drug discovery for schistosomiasis, a neglected tropical disease. Yet, these vaccines are under development and might be part of the solution if 3 phases of clinical trials are complete.

Despite these challenges, there has been significant research within the academic sector, and collaborative efforts through initiatives such as the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi) and the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) have been instrumental in amassing compound libraries. These libraries are being screened against various infectious diseases, including schistosomiasis, yielding several potential new compounds. Therefore, enhancing research and development efforts in antischistosomal drug discovery is both timely and essential.

Other chemical treatments, such as 1-N-diethylamino-ethyl-amino-4-methyl-9-thioxanthone hydrochloride (lucantone) and its main metabolite, 1-Nb-diethylaminoethylamino-(Hydroxymethyl)-9-thioxanthone (hican-tone), showed efficacy against S. mansoni and S. hematobium. Similarly, 1-(5-nitro-2-thiazolyl) imidazolidine-2-one (miridazole) was effective against S. hematobium and S. japonicum. Still, these drugs are no longer in use due to severe adverse reactions, including damage to the liver and kidneys, convulsions, psychoses, and hallucinations, which can affect the central nervous system.

There is a myriad of anti-anemic agents, such as hepcidin antagonists, novel iron formulations, activin receptor IIA ligand traps, and hypoxia inducible factor stabilizers, that could be promising new targets for treating both schistosomiasis and anemia.

7. Future directions

7.1. ANIMAL MODELS FOR STUDYING IRON FROM A HOST-PARASITE PERSPECTIVE

The findings in animal models reinforce this relationship between schistosomiasis and anemia, as demonstrated by McDonald et al., who investigated the relationships between the disease outcomes of Schistosoma japonicum infection and iron homeostasis. The aim of this study was to determine whether host iron status has an effect on schistosome maturation or egg production and to investigate the response of iron regulatory genes to chronic schistosomiasis infection in a host-parasite response in wild-type C57BL/6 and Transferrin Receptor 2 null mice infected with S. japonicum.

7.1.1. Iron overload

Transferrin receptor 2 null mice are a model of type 3 hereditary hemochromatosis and develop significant iron overload, resulting in increased iron stores at the onset of infection. The infectivity of schistosomes and egg production were assessed along with the subsequent development of granulomas and fibrosis. The response of the iron regulatory gene Hepcidin to infection and changes in iron status were assessed by real-time PCR and Western blotting. These results demonstrated that Hepcidin levels responded to changes in the iron status of the animals but were not significantly influenced by the inflammatory response. It also shown that with increased iron availability at the time of infection, there was greater development of fibrosis around granulomas. In conclusion, these findings indicate that chronic inflammation may not be the primary cause of anemia in schistosomiasis patients and suggest that increased iron availability, such as iron supplementation, may actually lead to increased disease severity.

7.1.2. Iron chelation

In contrast, according to Abdelgelil, the study utilized eighty 8-week-old male BALB/c mice divided equally into two primary cohorts: one consisting of healthy noninfected individuals and the other consisting of S. mansoni-infected mice. The healthy noninfected cohort was further subdivided into two groups of twenty mice each. The first group served as the normal control group and received 100 μl of normal sterile saline via daily intraperitoneal (IP) injection from the 2nd day post infection (PI) to the 42nd day PI. The second group was treated with 100 μl of deferoxamine (DFO) under the same conditions, and the effects of iron chelation were investigated in uninfected hosts. Similarly, the infected cohort was divided into two groups of twenty: the S. mansoni-infected DFO-untreated group received cercariae but without DFO, maintaining iron availability, whereas the S. mansoni-infected DFO-treated group was both infected and administered DFO from the 2nd day PI to the 42nd day PI. This design allows for a controlled investigation of the impact of iron deprivation on disease progression and the host response to S. mansoni infection. Simulating iron deprivation status with DFO administration diminished the growth, maturity and fecundity of S. mansoni, accompanied by a subsequent improvement in hepatic pathology. Normally, infection commences when cercariae penetrate human skin and transform into schistosomules. These schistosomules sequester iron predominantly in the form of heme sourced from the host’s hemoglobin, as well as from ferritin and transferrin. This iron uptake is crucial not only for the growth and sexual maturation of schistosomules into adult worms but also for oogenesis. While our findings suggest that DFO could serve as a beneficial treatment against schistosomal infection, it is important to note that DFO has not been considered for clinical trials targeting schistosomiasis. Therefore, although preliminary data indicate its efficacy in the laboratory setting, further investigation and validation in clinical settings are essential to confirm its safety and effectiveness as a therapeutic agent. DFO has a great affinity for ferric ions from ferritin, hemosiderin and transferrin but not for those from hemoglobin. In addition, Salvarani demonstrated that DFO improved the regulation of erythropoietin hormone production and could be used to alleviate chronic anemia accompanying rheumatoid arthritis cases. Thus, anemia is unlikely to occur with DFO treatment. These findings suggest that iron plays an important role in the host-parasite relationship and that iron is an important drug modulation.

There is a need for studies to isolate Schistosoma antigens, such as cercarial antigen preparations (CAPs), egg antigen (SEA) and soluble worm antigen protein (SWAP), to investigate how they can induce anaemia.

Besides schistosoma antigens, another potential antigen and immunomodulator is Schistosoma hemozoin which has been investigated by several researchers, and the results showed interestingly rules besides heme detoxification which play important roles in pathogenicity, immune modulation, iron supply for egg formation, and interactions with some anti-schistosomal drugs.

8. Layers of Fragility:

8.1. FIRST AND SECOND HIGHER HIERARCHICAL LEVEL – SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC AND SOCIOECONOMIC CONDITIONS: INTERSECTION OF ANEMIA AND SCHISTOSOMIASIS.

This level encompasses sociodemographic factors, including aspects such as geographic distribution, access to basic sanitation, and social inequalities affecting vulnerable populations. Within this level the presence of parasitic infections, both isolated and concomitant with anemia, exacerbates the prevalence of the condition, especially in low- and lower-middle-income countries. The lack of access to basic human rights, often neglected due to poverty, perpetuates a cycle of disease, particularly impacting vulnerable groups such as women, especially pregnant ones, and children. This level addresses the socioeconomic factors contributing to the spread and impact of anemia and schistosomiasis even before birth. Within this level, factors such as age, gender, and geographic location are analyzed to understand how their intersections further increase the vulnerability of populations. For instance, women, particularly pregnant ones, and children are especially susceptible to the compounded effects of these conditions.

While these hierarchical levels represent different approaches to understanding fragility, there are specific layers of intersection that can be analyzed individually.

8.2. THE INTERSECTIONS LAYERS BETWEEN ANEMIA AND SCHISTOSOMIASIS: POVERTY, GEOGRAPHIC VULNERABILITY; GENDER AND AGE CREATES AN AMPLIFIED RISK FOR VULNERABLE POPULATIONS

Poverty is a fundamental driver of both anemia and schistosomiasis. Limited access to healthcare, poor nutrition, and inadequate sanitation facilities are common in impoverished regions, increasing the risk of parasitic infections and their sequelae, such as iron-deficiency anemia. In such settings, the lack of resources to prevent or treat these conditions perpetuates a vicious cycle of illness and poverty, making poverty a critical layer of fragility.

Geographic location plays a significant role in the intersection of anemia and schistosomiasis. Regions endemic to schistosomiasis, often rural and with limited access to clean water and healthcare infrastructure, are particularly vulnerable. These conditions facilitate the spread of the parasite, leading to chronic infections that cause anemia through mechanisms such as blood loss and inflammation. The geographical isolation of these populations further hampers access to effective treatment and preventive measures, deepening the health disparities faced by these communities.

Gender is a significant factor in the susceptibility to anemia and schistosomiasis, particularly among women, especially of reproductive age ones as a cumulative risk. The heightened iron requirements associated with menstruation, pregnancy, and childbirth, coupled with the blood loss and impaired nutrient absorption resulting from schistosomiasis, significantly heighten the risk of developing severe anemia in this population.

Age is a critical factor in susceptibility to both diseases, particularly in children. Their developing immune systems and higher nutritional needs make them especially vulnerable. Chronic infections during childhood can impair physical and cognitive development, resulting in long-term consequences that go beyond immediate health impacts. In regions where both conditions are prevalent, the compounded effect on children can be devastating, perpetuating cycles of poor health and diminished educational and economic opportunities.

The intersection layers of these vulnerabilities—poverty, geographic isolation, and demographic factors like gender and age—creates a complex web of risk that amplifies the impact of anemia and schistosomiasis even before birth. Addressing these issues requires a multifaceted approach that considers the broader social determinants of health, including economic empowerment, access to education, and the strengthening of healthcare systems in endemic regions.

By understanding and addressing these layers of fragility, interventions can be more effectively designed to break the cycle and improve long term health outcomes for the most vulnerable populations and for these reasons, anemia and schistosomiasis warrant further investigation.

9. Conclusion:

Anemia and schistosomiasis remain significant public health concerns in low-income countries, contributing to substantial mortality and morbidity among vulnerable populations before birth. These conditions perpetuate a cycle of disease exacerbated by sociodemographic factors, poverty, educational deficiencies, inadequate access to healthcare, and insufficient public policies unmasking a sum of layers of fragility hard to overcome. Effective surveillance programs and eradication efforts require a multifaceted approach that addresses ecological, social, educational, political, and medical factors. Comprehensive and integrated treatment strategies are essential to break the cycle of disease and improve health outcomes in low-income regions. Sustained research and development efforts are crucial to discover and implement effective treatments, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for the most affected populations and overcoming praziquantel resistance in hotspots regions.

The intricate relationship between anemia and iron metabolism in the context of parasitic diseases, particularly schistosomiasis, warrants further investigation. Emerging evidence suggests a complex host-parasite interaction where iron metabolism could play a protective role. Current treatments for schistosomiasis fail to reverse pathological damage, such as fibrosis, underscoring the need for novel therapeutic approaches. Developing new drugs targeting iron metabolism and its consequences, understanding hemozoin modulations or development of schistosoma antigens could significantly reduce morbidity and mortality associated with both anemia and schistosomiasis.

Parodying the well-known phrase, ‘The whole is greater than the sum of its parts,’ we can say, ‘The weight is greater than the sum of the layers.’ The weight of these layers of fragility extends far beyond our immediate comprehension, inflicting lasting harm on vulnerable populations and stripping them of their fundamental right to health even before they are born.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors declare that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement:

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript. JPAS and FRML received no grants in field of this manuscript. JPAS received funding from FIOCRUZ under grant VPPIS-004-FIO-22-2-41.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ) for supporting JPAS and FRML.

References

- GBD 2021 Anaemia Collaborators. Prevalence, years lived with disability, and trends in anaemia burden by severity and cause, 1990-2021: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10(9):e713-e734. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00160-6

- Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M, et al. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood. 2014;123(5):615-624. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-06-508325

- Stevens GA, Paciorek CJ, Flores-Urrutia MC, et al. National, regional, and global estimates of anaemia by severity in women and children for 2000–19: a pooled analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(5):e627-e639. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00084-5

- World Health Organization (WHO), THE GLOBAL HEALTH OBSERVATORY (GHO). Schistosomiasis. Accessed May 16, 2024. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/schistosomiasis

- King CH, Galvani AP. Underestimation of the global burden of schistosomiasis. The Lancet. 2018;391(10118):307-308. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30098-9

- Kassebaum NJ. The Global Burden of Anemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30(2):247-308. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2015.11.002

- Lanier JB, Park JJ, Callahan RC. Anemia in Older Adults. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(7):437-442.

- Araujo Costa E, De Paula Ayres-Silva J. Global profile of anemia during pregnancy versus country income overview: 19 years estimative (2000–2019). Ann Hematol. Published online May 26, 2023. doi:10.1007/s00277-023-05279-2

- Kinyoki D, Osgood-Zimmerman AE, Bhattacharjee NV, et al. Anemia prevalence in women of reproductive age in low- and middle-income countries between 2000 and 2018. Nat Med. 2021;27(10):1761-1782. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01498-0

- Sun J, Wu H, Zhao M, Magnussen CG, Xi B. Prevalence and changes of anemia among young children and women in 47 low- and middle-income countries, 2000-2018. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;41:101136. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101136

- Leir SA, Foot O, Jeyaratnam D, Whyte MB. Schistosomiasis and associated iron-deficiency anaemia presenting decades after immigration from sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(4):e227564. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-227564

- Grotto HZW. Fisiologia e metabolismo do ferro. Rev Bras Hematol E Hemoter. 2010;32:08-17. doi:10.1590/S1516-84842010005000050

- Koury MJ. Abnormal erythropoiesis and the pathophysiology of chronic anemia. Blood Rev. 2014;28(2):49-66. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2014.01.002

- Grotto HZW. Metabolismo do ferro: uma revisão sobre os principais mecanismos envolvidos em sua homeostase. Rev Bras Hematol E Hemoter. 2008;30(5). doi:10.1590/S1516-84842008000500012

- Dugdale M. ANEMIA. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2001;28(2):363-382. doi:10.1016/S0889-8545(05)70206-0

- Vaulont S. Métabolisme du fer. Arch Pédiatrie. 2017;24(5):5S32-5S39. doi:10.1016/S0929-693X(17)24007-X

- Camaschella Clara. Iron-Deficiency Anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1832-1843. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1401038

- Milman N, Taylor CL, Merkel J, Brannon PM. Iron status in pregnant women and women of reproductive age in Europe. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(Suppl 6):1655S-1662S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.117.156000

- WHO Guideline on Use of Ferritin Concentrations to Assess Iron Status in Individuals and Populations. World Health Organization; 2020. Accessed June 3, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK569880/

- Cappellini MD, Santini V, Braxs C, Shander A. Iron metabolism and iron deficiency anemia in women. Fertil Steril. 2022;118(4):607-614. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.08.014

- Gulec S, Anderson GJ, Collins JF. Mechanistic and regulatory aspects of intestinal iron absorption. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307(4):G397-G409. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00348.2013

- Rouault TA. The role of iron regulatory proteins in mammalian iron homeostasis and disease. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(8):406-414. doi:10.1038/nchembio807

- Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Camaschella C. Two to Tango: Regulation of Mammalian Iron Metabolism. Cell. 2010;142(1):24-38. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.028

- Muckenthaler MU, Rivella S, Hentze MW, Galy B. A Red Carpet for Iron Metabolism. Cell. 2017;168(3):344-361. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.034

- Naigamwalla DZ, Webb JA, Giger U. Iron deficiency anemia. Can Vet J Rev Veterinaire Can. 2012;53(3):250-256.

- Cappellini MD, Musallam KM, Taher AT. Iron deficiency anaemia revisited. J Intern Med. 2020;287(2):153-170. doi:10.1111/joim.13004

- Pagani A, Nai A, Silvestri L, Camaschella C. Hepcidin and Anemia: A Tight Relationship. Front Physiol. 2019;10. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.01294

- Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, et al. Hepcidin Regulates Cellular Iron Efflux by Binding to Ferroportin and Inducing Its Internalization. Science. 2004;306(5704):2090-2093. doi:10.1126/science.1104742

- The mutual control of iron and erythropoiesis – Camaschella – 2016 – International Journal of Laboratory Hematology – Wiley Online Library. Accessed May 22, 2024. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijlh.12505

- Scholl TO. Maternal iron status: relation to fetal growth, length of gestation, and iron endowment of the neonate. Nutr Rev. 2011;69(suppl_1):S23-S29. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00429.x

- Hercberg S, Preziosi P, Galan P. Iron deficiency in Europe. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(2B):537-545. doi:10.1079/phn2001139

- CDC. About Schistosomiasis. Schistosomiasis. March 11, 2024. Accessed May 23, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/schistosomiasis/about/index.html

- Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030. Accessed May 23, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010352

- Wang L, Wu X, Li X, et al. Imported Schistosomiasis: A New Public Health Challenge for China. Front Med. 2020;7:553487. doi:10.3389/fmed.2020.553487

- Kumar V, Gryseels B. Use of praziquantel against schistosomiasis: a review of current status. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1994;4(4):313-320. doi:10.1016/0924-8579(94)90032-9

- Fallon PG, Tao LF, Ismail MM, Bennett JL. Schistosome resistance to praziquantel: Fact or artifact? Parasitol Today. 1996;12(8):316-320. doi:10.1016/0169-4758(96)10029-6

- Santos ET. Schistosoma mansoni: avaliação da fibrose hepática em camundongos submetidos à quimioterapia e reinfectados. Published online 2011. Accessed June 27, 2024. https://www.arca.fiocruz.br/handle/icict/5833

- Meister I, Leonidova A, Kovač J, Duthaler U, Keiser J, Huwyler J. Development and validation of an enantioselective LC–MS/MS method for the analysis of the anthelmintic drug praziquantel and its main metabolite in human plasma, blood and dried blood spots. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016;118:81-88. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2015.10.011

- Olveda RM, Acosta LP, Tallo V, et al. Efficacy and safety of praziquantel for the treatment of human schistosomiasis during pregnancy: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):199-208. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00345-X

- Malhado M, Pinto DP, Silva ACA, et al. Preclinical pharmacokinetic evaluation of praziquantel loaded in poly (methyl methacrylate) nanoparticle using a HPLC–MS/MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016;117:405-412. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2015.09.023

- Cheng L, Guo S, Wu W. Characterization and in vitro release of praziquantel from poly(ɛ-caprolactone) implants. Int J Pharm. 2009;377(1):112-119. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.05.007

- Katz N, Coelho PMZ. Clinical therapy of schistosomiasis mansoni: The Brazilian contribution. Schisto Res Braz. 2008;108(2):72-78. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.05.006

- Novaes MRCG, Souza JP de, Araújo HC de. Síntese do anti-helmíntico praziquantel, a partir da glicina. Quím Nova. 1999;22.

- Cioli D, Pica-Mattoccia L, Basso A, Guidi A. Schistosomiasis control: praziquantel forever? Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2014;195(1):23-29. doi:10