Preclinical Study of CLX-155A in Colon Cancer Models

Preclinical Evaluation of CLX-155A: A Novel 5-FU and Valproic Acid Prodrug in Nude Mouse Model for Activity in Colon Cancer

John M. York, PharmD, MBA ¹⁻²⁻³, Michika Maeda, MD ¹, Giovanni Lara, PharmD ¹, Mahesh Kandula, M.Tech, MBA⁴⁻⁵, and Subbu Apparsundaram, PhD ⁴⁻⁵

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 April 2025

CITATION: York, JM., Maeda, M., et al., 2025. Preclinical Evaluation of CLX-155A: A Novel 5-FU and Valproic Acid Prodrug in Nude Mouse Model for Activity in Colon Cancer. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(4). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i4.6224

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i4.6224

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Traditional pyrimidine antimetabolic chemotherapy agents like 5-FU and capecitabine face challenges such as resistance, toxicity, and variability in patient response, highlighting the need for new therapeutic strategies to improve patient outcomes. CLX-155A is a novel oral prodrug that combines 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and valproic acid (VPA), aiming to enhance chemotherapy efficacy through synergistic mechanisms. This preclinical study addressed research questions relative to CLX-155A’s preclinical activity, single-dose pharmacokinetic (PK) profile, and relative effects compared with capecitabine in FoxN1 athymic nude mouse models of human colorectal cancer (CRC).

This study assessed the anticancer efficacy of CLX-155A in a colorectal cancer xenograft mouse model utilizing seven groups (n=10/group) of FoxN1 athymic nude female mice. Investigators inoculated the FoxN1 athymic nude female mice with cancer cells and subsequently treated them with varying doses of CLX-155A, involving twice-daily (150 and 500 mg/kg twice daily) and once-daily (300 and 1000 mg/kg/day) schedules. The capecitabine group was a positive control, dosed at 1000 mg/kg/day (500 mg/kg/twice daily or 1000 mg/kg/day). They monitored tumor growth as the primary endpoint and evaluated the pharmacokinetic profile of 5-FU and its precursors (5’-DFCR, 5’-DFCR), along with that of VPA.

CLX-155A demonstrated a significant dose-dependent tumor growth (p<0.05) inhibition versus vehicle and was comparable to capecitabine. The evaluation of its single-dose pharmacokinetic profile reflected defined peaks for 5-FU and its precursors (5’-DFCR, 5’-DFCR), higher area under the curve (AUC) versus capecitabine, sustained release characteristics, and defined peaks and AUCs for valproic acid.

Overall, CLX-155A exhibits promising preclinical efficacy in a nude xenograft mouse model of colorectal cancer. Its dual-action mechanism and improved pharmacokinetic profile suggest potential advantages over existing therapies. Further studies are warranted to explore its clinical potential and optimize dosing strategies.

Keywords: Capecitabine, CLX-155A, Colorectal cancer, 5-FU, Nude mouse model, Valproic acid

Introduction

Pyrimidine analogs have long played a crucial role in cancer treatment by interfering with DNA and RNA synthesis, which are essential for cell replication and survival. Among these, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) stands out as a widely used intravenous (IV) chemotherapeutic agent, demonstrating significant efficacy in treating solid tumors, including colorectal cancer. 5-FU mimics the pyrimidine nucleotide uracil, inhibiting thymidylate synthase and incorporating it into RNA and DNA, thereby disrupting the normal function of these nucleic acids and leading to cell death.

Despite its effectiveness, 5-FU often causes severe side effects, like myelosuppression, mucositis, and cardiotoxicity, necessitating continuous infusion to maintain therapeutic levels. It also has issues with resistance that limits its effectiveness and drug availability due to manufacturing, supply, and demand.

To address some of 5-FU’s limitations, researchers developed capecitabine, an oral prodrug of 5-FU. Capecitabine converts enzymatically to 5-FU in the liver and tumor tissues, offering a more convenient and potentially less toxic alternative to intravenous 5-FU. This oral administration allows for more flexible dosing schedules and can improve patient compliance. However, capecitabine also presents challenges, including variability in patient metabolism, liver function dependency for activation, and significant gastrointestinal and dermatological toxicities, such as diarrhea and hand-foot syndrome. These adverse effects often necessitate dose reductions and treatment interruptions, which can compromise the overall efficacy of the therapy.

In cancer therapy, unmet needs include overcoming drug resistance, reducing toxicity, and improving patient compliance. Drug resistance is a significant hurdle in cancer treatment, as cancer cells can develop mechanisms to evade the effects of chemotherapy, leading to treatment failure. Additionally, the toxicity associated with many chemotherapeutic agents can limit the use of these therapeutics, particularly in patients with comorbidities or those who are elderly. Improving patient compliance is also crucial, as complex or inconvenient dosing regimens can lead to suboptimal adherence to treatment protocols.

These gaps highlight the necessity for novel therapeutic strategies that enhance efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Furthermore, for 5-FU, unmet needs include consistent drug supply, mitigating resistance issues, and alternative routes of delivery to mimic continuous infusion. For capecitabine, such needs include consistent drug levels and the limiting of gastrointestinal, hand, and foot syndrome issues (50% of patients), liver effects, and dose adjustments in elderly patients as well as patients with hepatic or renal disease.

CLX-155 offers an innovative approach to addressing these unmet needs. It encompasses an innovative prodrug that combines 5-FU with caprylic acid, designed to be metabolized in the intestinal wall rather than the liver. This latter component possesses antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and digestive health capabilities and adds to 5-FU’s action via several anticancer mechanisms established via multiple models, including apoptosis induction, cell proliferation inhibition, gene expression modulation, and cancer cell viability reduction.

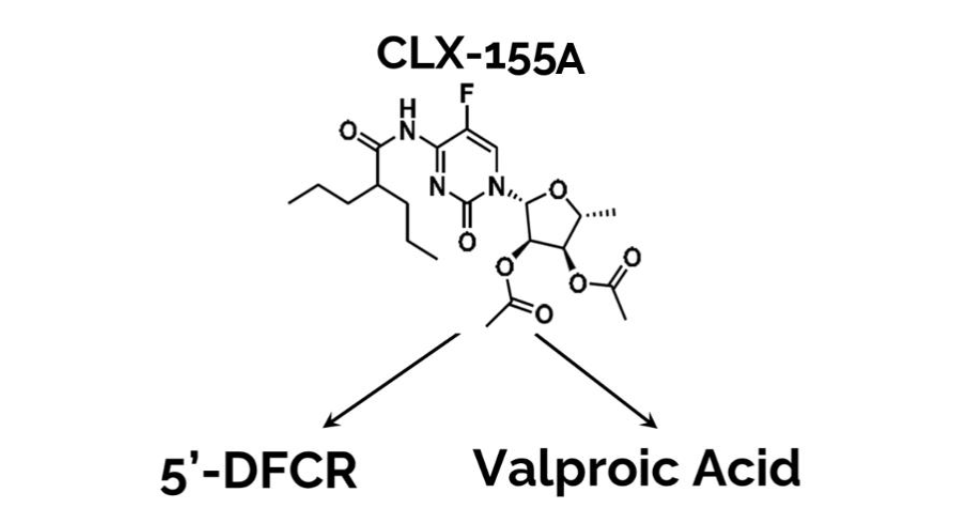

Building on these fundamental characteristics, CLX-155A incorporates valproic acid (VPA), a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor (Figure 1), to further enhance anticancer activity through epigenetic modulation. Valproic acid induces apoptosis, inhibits cell proliferation, and modulates gene expression, making it a valuable addition to cancer therapy.

HDAC inhibitors like valproic acid play a crucial role in cancer therapy by altering the acetylation status of histones, thereby affecting gene expression and promoting cancer cell death. The combination of 5-FU and valproic acid in CLX-155A aims to leverage these synergistic effects to improve treatment outcomes in colorectal cancer.

This study addresses the three relevant research questions. First, what is the anticancer activity of CLX-155A in preclinical models of colorectal cancer? Second, what is CLX-155A’s single-dose pharmacokinetic profile in a cancer model? Finally, how do such effects compare to existing treatments like capecitabine?

This comprehensive evaluation aims to provide a robust preclinical foundation for the potential clinical application of CLX-155A, addressing critical gaps in current cancer therapies and paving the way for more effective and tolerable treatment options for patients with colorectal cancer. This paper’s structure first presents the methods used in the preclinical evaluation of CLX-155A, including the design of a xenograft athymic nude mouse model for colorectal cancer, dosing regimens, and pharmacokinetic analyses. Next, the results section details the findings on tumor growth inhibition, pharmacokinetic profiles, and toxicity assessments. Finally, the discussion considers the implications of these results, comparing them with relevant literature and exploring the potential mechanisms underlying the observed activity of CLX-155A in the colorectal cancer model, with specific interest in its pharmacokinetic profile and the role of VPA.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

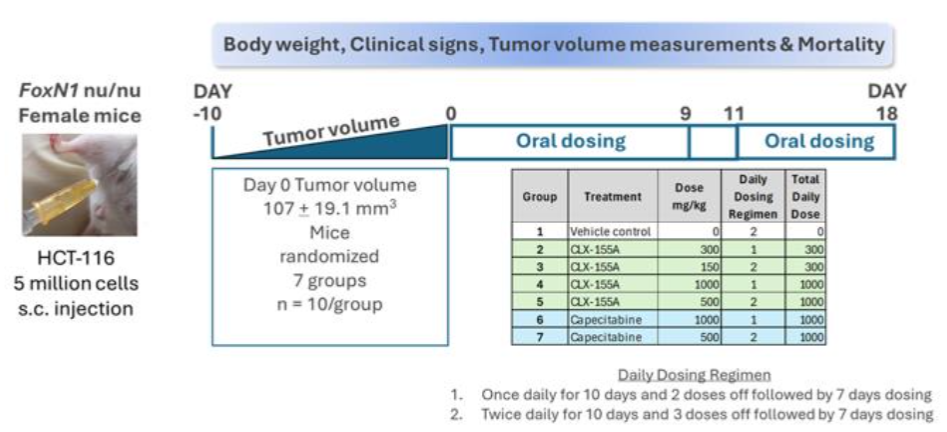

The study (Figure 2) utilized seven groups (n=10/group) of FoxN1 athymic nude female mice sourced from Vivo Bio Tech (Hyderabad, India). Preclinical studies have established the validity of nude mouse models for assessing the efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents for colorectal cancer. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee reviewed and approved all procedures involving animal care and use prior to the study. Animal care and use adhered to the principles outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Edition, 2010 (National Research Council). The experimentation facility holds the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International accreditation.

ANIMALS AND HANDLING

All animals resided in groups of five within individually ventilated cages in a dedicated rodent quarantine room within an immunocompromised facility for one week. Daily monitoring occurred throughout the one-week quarantine period to detect any clinical signs of disease. Following the completion of the quarantine period, healthy animals transitioned to an experimental room for seven days to acclimate to the experimental conditions. Animals resided in a continuously monitored temperature and humidity-regulated aseptic and access-controlled environment (target ranges: temperature 22 ± 2°C; relative humidity 60 ± 4%; and 60 air changes per hour), with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and under barrier (quarantine) conditions. Investigators routinely monitored the entire facility to detect any airborne infections. The animals received an autoclaved commercial diet (Nutrilab Rodent Feed, cylindrical-shaped pellets; Maringá, Paraná, Brazil), and had free access to autoclaved water.

CANCER CELL LINES AND INOCULATION

This study utilized the human colon cancer cell line HCT-116, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Virginia, USA. The culture media used to grow the HCT-116 cell line consisting of McCoy’s 5a medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Investigators harvested cells by trypsinization at 70-80% confluence and then re-suspended cells in a serum-free medium prior to animal inoculation. Investigators implanted the HCT-116 cells (5 million cells/site) subcutaneously in the dorsal right flank. Injections contained viable HCT-116 cells in serum-free medium at a concentration of 5 × 106/100 μL mixed with an equal volume of Matrigel (1:1 ratio) for implanting at the subcutaneous site per mouse. Each injection consisted of 200 μL per site using a 1 mL BD syringe attached to a 23-gauge needle. Investigators measured the size of the xenografts approximately ten days after cell injection and once the xenografts became palpable. Investigators randomized animals into seven groups (n = 10 per group) once the tumors reached an average tumor volume size of ~107 ± 19.1 mm3 at Day 0, ensuring comparable average tumor volumes across all groups.

PREPARATION OF EXPERIMENTAL TREATMENTS

The administration of all compound formulations occurred within one hour of preparation. CLX-155A formulations consisted of 2600 mg of Capryol 90, 200 mg of polysorbate 80, and 8 mL of water in sufficient quantities to make solutions of 15.625, 31.25, and 62.5 mg/mL for doses of 125, 250, and 500 mg/kg CLX-155A respectively. Investigators prepared the capecitabine 1000 mg/kg dose in 0.5% w/v hydroxypropyl methylcellulose in 40 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0 in 0.2 μm filtered water vehicle for a capecitabine dose concentration of 100 mg/mL, and a dose volume of 10 mL/kg.

TREATMENT GROUPS AND EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

For the colorectal cancer investigation, on Day 0, animals in Group 1 (Sham; n = 10) received an oral vehicle control at a dose volume of 8 mL/kg, and animals in Groups 2 to 5 (n = 10/group) received CLX-155A doses at 300 mg/kg once daily (QD), 150 mg/kg twice daily (BID), 1000 mg/kg once daily, and 500 mg/kg twice daily, respectively. Animals in Groups 6 and 7 (n= 10/group) received capecitabine at 1000 mg/kg once daily and 500 mg/kg twice daily, respectively. Researchers administered the doses through oral gavage at approximately the same time each day. They adjusted the dose volume (8 mL/kg for CLX-155A and 10 mL/kg for capecitabine) based on the most recently recorded body weight of each mouse. Doses were selected based on the results of a 7-day repeated dose range-finding toxicity study in FoxN1 nude mice. Treatment administration occurred initially for 10 days (Day 0-9) for all animals. Those receiving once-daily treatment had two doses off (Days 10 and 11) after this initial treatment, then restarted treatment for seven more days (Days 12-18) to complete treatment. The twice daily-treated animals had three doses off (Days 10 and 11) and then restarted for seven more days (Days 11-18).

MEASUREMENTS AND ASSESSMENTS

The study team conducted daily mortality checks throughout the investigation. They monitored animals daily for visible clinical signs (e.g., illness and behavioral changes) and tumors for necrosis, ulceration, wounds, and scars throughout the study. Recordings of body weights for all animals occurred on the first day of treatment and continued three times weekly. Evaluation of treatment toxicity relied on the presence of any body weight loss. For evaluating anti-tumor activity, the investigators recorded HCT-116 xenograft growth on Days 1, 4, 6, 8, 11, 13, 15, and 18. They used a digital Vernier caliper to measure tumor length and width. Determination of tumor volumes involved calculating tumor length × (tumor width)² × 0.52. Calculations for tumor growth inhibition involved comparing the tumor volume on a given day to that from the initial measurement (Day 1 or 0, depending on the study). The investigators terminated treatment and humanely sacrificed animals if they exhibited severe clinical signs of toxicity, more than a 15% drop in body weight in a day, more than a 20% drop in body weight from pre-test level, or tumor volumes exceeding 2000 mm³.

PHARMACOKINETIC ASSESSMENTS

Investigators analyzed the pharmacokinetic characteristics of both CLX-155A and capecitabine, specifically for the animals in the 1000 mg/kg once-daily groups. Blood sample collection occurred at 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 hours following a single dose to determine 5-FU, 5’-DFCR, 5’-DFUR, and valproic acid plasma concentrations. The analysis involved time versus plasma concentration profiles. Pharmacokinetic analysis engaged a noncompartmental analysis using WinNonlin Version 7.0 (Certara, Princeton, NJ) to calculate the area under the curve to the last measurable time point (AUC0-t), maximum concentration (Cmax), and time to maximum concentration (Tmax).

ANALYSIS AND STATISTICS

This study used Prism 5.0 for all statistical calculations. Assessment of the primary endpoint, tumor volume, involved a two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests, and a p-value <0.05 compared to sham was considered significant. The percent of tumor growth inhibition involved the following formula:

Calculation of tumor growth rate involved the ratio between tumor volume on the day of measurements and tumor volume on the first day of drug treatment. Complete response referred to a tumor with a volume <25 mm³ for at least three consecutive measurements, while partial response indicated a tumor that decreased below 50% of its initial volume for at least three consecutive measurements. Investigators expressed the results as means ± the standard deviation

Results

ANTI-TUMOR ACTIVITY

Within this study, of the 70 randomized animals, 67 completed the study, and three expired: one with CLX-155A (500 mg twice daily) and two with capecitabine (500 mg twice daily).

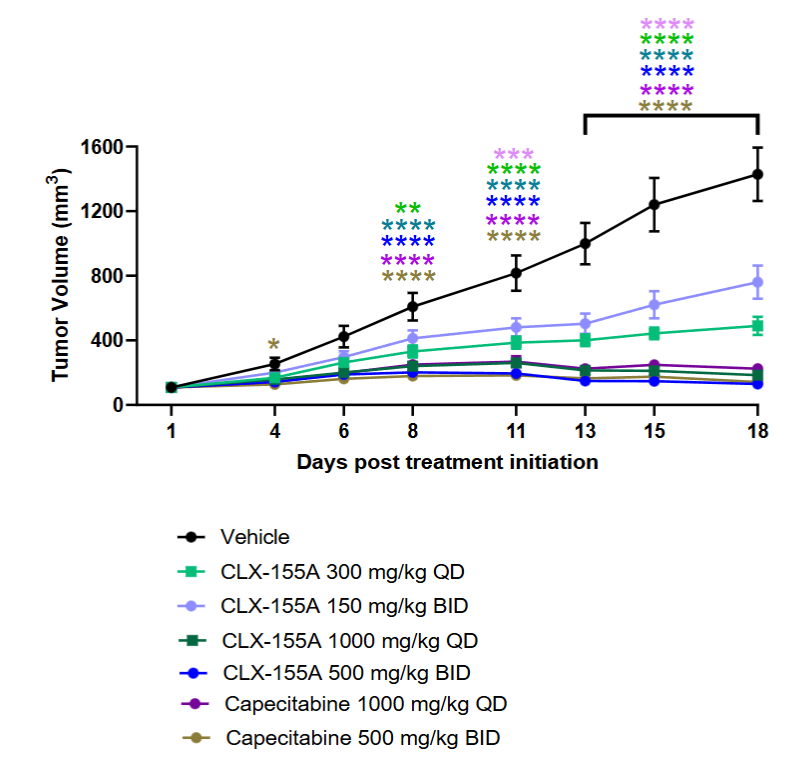

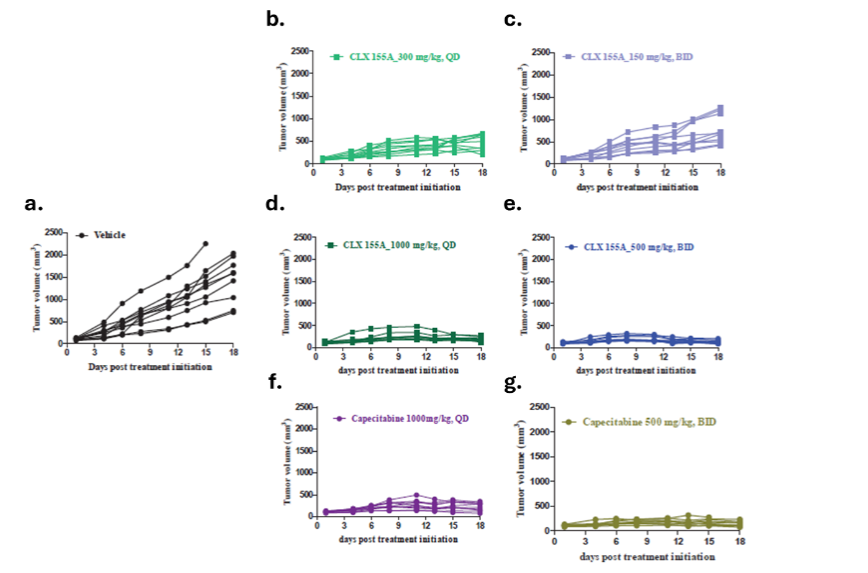

As highlighted in Figures 3 and 4, multiple doses of CLX-155A (once daily, twice daily) demonstrated significant tumor growth inhibition (p<0.01) compared with the vehicle control on Day 8. Results were dose-dependent: 300 mg/kg once daily (p<0.05), and both the 1000 mg/kg once daily and 500 mg/kg twice daily (p<0.0001). On Day 11, all CLX-155A groups were significant (p<0.0001), except for 150 mg/kg twice daily (p<0.001). The higher doses of CLX-155A showed greater efficacy, with the 1000 mg/kg/day dose (both once daily and twice daily schedules) achieving the most substantial tumor reduction (Figure 3). This effect was consistent across all animals in the 1000 mg/kg/day groups and most pronounced in the 500 mg/kg/day twice daily group (Figure 4). Also, the once-daily dosing schedule of 300 mg/kg/day demonstrated numerically better anti-tumor activity than the twice-daily dosing schedule at 150 mg/kg twice daily. Noteworthy was that the effects of CLX-155A at 1000 mg/kg/day were consistent with those with capecitabine at 1000 mg/kg/day.

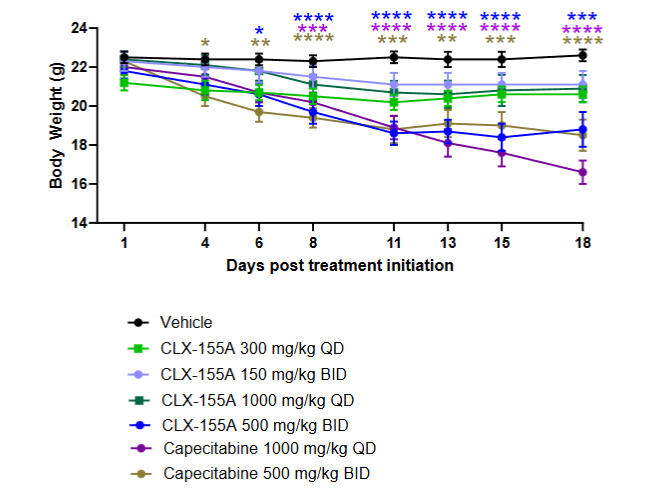

EFFECTS ON WEIGHT

Weight loss was one drug-related effect noted with both treatments compared to the vehicle. It was dose-dependent and significant with the higher doses (p<0.001 on Days 13, 15, and 18). Animals in the capecitabine 1000 mg/kg once daily group showed more extensive weight loss at these time points (p<0.0001), and the twice-daily groups for both drugs had significant weight loss at these days (p<0.0001 for capecitabine, p<0.001 for CLX-155A).

PHARMACOKINETIC PROFILE

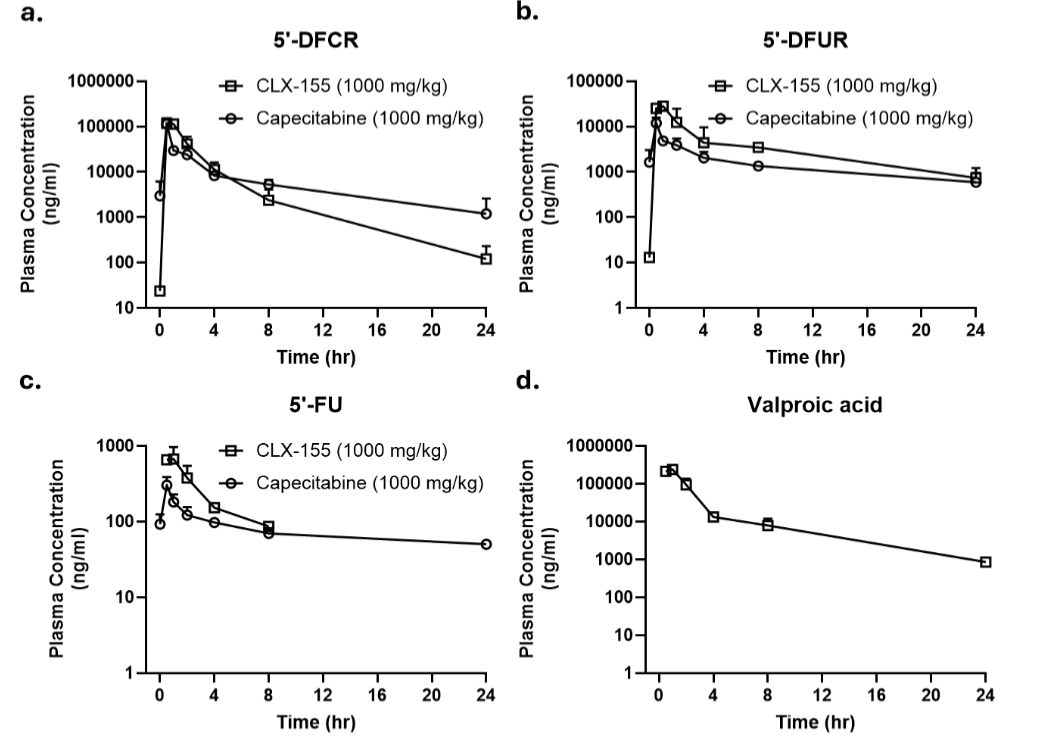

CLX-155A and capecitabine’s single-dose pharmacokinetic profiles displayed defined peaks and accumulation of 5-FU and its precursors. Both drugs at 1000 mg/kg once daily showed defined Tmax within an hour of administration for 5-FU and its precursors. CLX-155A showed higher peaks (NS) for 5’-DFUR and 5-FU. CLX-155A’s mean AUC0-t for 5’-DFCR, 5’-DFUR, and 5-FU was higher than with capecitabine. This observation suggested a more prolonged and consistent release of the active drug. Specifically, the AUC0-t for 5’-DFCR was 265.1 µg.h/mL for CLX-155A compared to 203.3 µg.h/mL for capecitabine. The AUC0-t for 5-FU was 2.05 µg.h/mL for CLX-155A compared to 1.89 µg.h/mL for capecitabine. The half-life for 5’-DFCR, 5’-DFUR, and 5-FU for CLX-155A were 3.22, 7.22, and 7.57, whereas for capecitabine, these were 11.69, 3.0, and 7.55 hours, respectively. Finally, the AUC0-t for valproic acid was 551.576 μg*h/mL, with a Cmax of 239715 ng/mL and a Tmax of 1 hour, reflecting efficient oral absorption and metabolism by the intestinal gut. The half-life was 5.05 hours.

| PK Parameters | 5′-DFCR | 5′-DFUR | 5-FU | Valproic acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLX-155A | 265.12 | 106.10 | 2.05 | 551.76 |

| Capecitabine | 203.27 | 40.26 | 1.89 | |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 118.54 | 28.18 | 0.67 | 239.72 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| t1/2 (h) | 3.22 | 7.57 | 3.00 | 5.05 |

Discussion

This work describes the first effort to document the activity of the combination prodrug CLX-155A in the athymic nude mouse xenograft model of colorectal cancer. This study evaluated doses ranging from 300 to 1000 mg/kg/day and twice daily and once-daily schedules. It sought to address the research question around these parameters and the impact on activity in this model, in which treatment persisted over 18 days. The results from this study addressed this question. CLX-155A displayed significant effects on % tumor growth inhibition (p<0.005) across all doses and schedules as compared with vehicles. The effects were dose-dependent, with the most significant effect at 1000 mg/kg/day for either the once daily at 1000 mg/kg or the twice daily 500 mg/kg doses (p<0.0001).

Prior work with CLX-155, a prodrug that breaks into 5’-DFCR precursor and caprylic acid, provided complementary observations relative to activity and survival when administered in the colorectal cancer model for five days on two-off schedules for three cycles. Boyette and colleagues reported that CLX-155 demonstrates statistically significant (p<0.0001) dose-dependent % tumor growth inhibition at 125, 250, and 500 mg/kg/day versus vehicle control. The 500 mg/kg/day dose showed similar effects versus the positive control, capecitabine, at 1000 mg/kg/day. Furthermore, complete regression occurred in two of the ten animals. Such data only complemented the findings in the CLX-155A study, which had a shorter treatment period.

Furthermore, studies have evaluated CLX-155A in a nude xenograft mouse model of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). The triple-negative breast cancer model tested CLX-155A as monotherapy at 1000 mg/kg/day, as well as combination therapy with paclitaxel. As in the CLX-155A colorectal cancer model, the triple-negative breast cancer study utilized comparisons with vehicle and capecitabine at 1000 mg/kg/day. Results showed that CLX-155A had a significant effect on tumor growth inhibition (p<0.05) compared to vehicle control and demonstrated increased efficacy when paired with paclitaxel. When compared to capecitabine, CLX-155A showed superior effect, demonstrating comparable effectiveness as capecitabine when used in coordination with paclitaxel.

In addition to CLX-155A and CLX-155, previous capecitabine research utilizing xenograft models in mice has shown that capecitabine is effective against various cancers. This drug has demonstrated significant anti-tumor activity across different xenograft models, often outperforming 5-FU alone. Specifically, in colon cancer, capecitabine’s ability to inhibit tumor growth varied between 17% and 101% across different human colon cancer cell lines, with the highest inhibition observed in the HCT-116 cell line at 101%. Another study comparing capecitabine and 5-FU at their maximum tolerated doses in an HCT-116 human colon cancer xenograft model found that capecitabine inhibited tumor growth by 86% after seven weeks. These findings were consistent with the tumor growth inhibition rates observed in this study, where maximum doses of capecitabine achieved 94.1% tumor growth inhibition and CLX-155A 96.6% tumor growth inhibition on Day 15.

Another area of interest in this study was the effect on weight changes, which was not a primary assessment. The percentage change findings in body weight during and after treatment reflected insights into the animals’ general health and treatments’ potential toxicities. Both CLX-155A and capecitabine showed significant effects on weight versus vehicle (p<0.05 for all). Reductions were dose- and schedule-dependent. The effect appeared to level off after a break in treatment before the next cycle. Capecitabine at 1000 mg/kg once daily displayed the most pronounced effect in the colorectal cancer study. Such observations might suggest that the higher single daily administered dose might have exerted a more bolus-like, producing a higher peak or drug accumulation during the treatment time. This dosing strategy and its resultant pharmacokinetic behavior could have led to gastrointestinal effects impacting food intake or absorption or some other type of metabolic phenomena. However, while CLX-155A’s 1000 mg/kg/day single-dose pharmacokinetic peak for 5’-DFUR and 5-FU and AUC0-t were higher than with capecitabine in the colorectal cancer study, its weight loss was lower in this investigation.

Another observation involved mortality, which was not a primary assessment of the study. Considering the long period of treatment (16 days of treatment), only one CLX-155A and two capecitabine animals expired. All were on the 500 mg twice-daily schedule. Interestingly, in the CLX-155 colorectal cancer study, all animals survived, whereas two animals in the capecitabine group expired. Studies have tied capecitabine’s impact on mortality to higher doses due to toxicity. Additionally, Liu and colleagues highlighted that capecitabine maintenance therapy at doses of 1,000 mg/m² twice daily (approximately 54.05 mg/kg/day) in nasopharyngeal carcinoma models resulted in manageable toxic effects but also noted instances of progression or death. Midgley and Kerr discussed the challenges of determining the optimal dose of capecitabine to balance efficacy and safety, noting that high doses, such as 1,250 mg/m² twice daily (approximately 67.57 mg/kg/day), could lead to significant toxicity and mortality.

These researchers also monitored changes in body weight throughout the study. Four animals showed weight loss: two in the CLX-155 500 mg/kg group and two in the capecitabine group. Bodyweight reductions in such studies are not uncommon. Multiple capecitabine preclinical studies report that the drug caused weight loss. This weight loss often results from the drug’s gastrointestinal toxicity, which leads to reduced food intake. For instance, Ishikawa and colleagues reported significant weight loss in animals treated with capecitabine, especially at higher doses. Similarly, Kolinsky and colleagues found that capecitabine administration decreased body weight in colorectal cancer xenograft models. Researchers noted that higher doses led to more pronounced weight reduction. Interestingly, these weight loss and mortality findings underscore the importance of careful dose management in preclinical studies to minimize adverse effects while maximizing therapeutic effects.

The pharmacokinetic profiles for single-dose CLX-155A and capecitabine at the 1000 mg/kg/day dose in the colorectal cancer study might offer some insights. CLX-155A showed higher Cmax at 1 hour and AUC0-t versus capecitabine for 5-FU and its precursors. However, it showed a much lower half-life for these precursors and 5-FU than capecitabine. Finally, CLX-155A also provided a distinct valproic acid Cmax at 1 hour and AUC0-t. Such pharmacokinetic characteristics might offer insight into both dose activity effects. Prior work with CLX-155 reinforced these single-dose pharmacokinetic characteristics, showing proportionality to the administered dose, delay in 5’-DFCR and 5′-DFUR, higher 5-FU AUC0-t exposure versus capecitabine at 500 and 1000 mg/kg, and an infusion-like conversion of precursors to 5-FU. Such findings might explain the similar efficacy of CLX-155 at 500 mg/kg/day to that of capecitabine at 1000 mg/kg/day. Such a profile provides one explanation for the activity profiles seen in both the CLX-155 colorectal cancer and CLX-155A colorectal cancer models.

The other explanation for CLX-155A’s activity in these models might be due to the presence of valproic acid, in which intestinal enzymes cleave from the prodrug to this active compound and the 5-FU precursor, 5’-DFCR. This agent, primarily known as an anticonvulsant and mood stabilizer due to its inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels, inhibition of calcium channels, and increasing GABAnergic neurotransmission, possesses anticancer activities, including histone deacetylase inhibition (leading to gene expression changes promoting cell cycle arrest, differentiation, and apoptosis), cell cycle arrest, apoptosis induction, and anti-angiogenesis effects.

Further, valproic acid enhances the efficacy of other anticancer treatments, including chemotherapy and radiotherapy, by sensitizing cancer cells to these treatments. It also shows activity in multiple animal cancer models, including glioma, pancreatic, breast cancer, and bladder. The breast cancer model by Terranova-Barberio and colleagues is notable in that valproic acid potentiates capecitabine’s anticancer activity via thymidine phosphorylase expression induction.

To date, the US Food and Drug Administration has approved four HDAC inhibitors for the treatment of hematological malignancies: vorinostat, romidepsin, belinostat, and panobinostat. HDAC inhibitors have shown positive responses in hematological malignancies. Relevant to solid tumors, recent research has also shown clinical applications of HDAC inhibitors in gliomas, breast cancer, and pancreatic cancer. However, some studies suggest that HDAC inhibitors, combined with another agent, can yield additional anti-tumor activity. In a syngeneic mouse tumor model, the combination of low-dose trichostatin-A, an HDAC inhibitor, with anti-PD-L1 enhanced the tumor reduction and prolonged survival of tumor-bearing mice when compared to monotherapy with either treatment alone. In another study utilizing xenograft models with cell lines from multiple solid tumor lineages, combining paclitaxel and either clinostat or ACY-241, both HDAC inhibitors, also enhanced the cell proliferation and increased cell death compared to either agent alone.

Finally, investigators have initiated multiple clinical studies of valproic acid in solid tumors, including glioblastoma, advanced solid tumors, head and neck cancer, and acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes.

Like all research, this study possesses some limitations. While the study provides valuable insights, it is important to recognize their limitations. Notable is the use of the HCT-116 human colorectal cancer xenograft model in Foxn1 athymic nude mice. Although xenograft models are helpful in studying anti-tumor efficacy, they lack an intact immune system. This absence of immune responses may not fully capture the complex interactions between the immune system and the tumor microenvironment observed in human subjects. The model used in this study addressed a specific question as an initial activity signal, but its lack of tumor metastasis does not fully represent advanced disease. Therefore, further evaluation and confirmation of CLX-155A’s efficacy in other colorectal cancer models, such as genetically engineered mouse models, patient-derived xenograft models, and patient-derived organoid models, are necessary.

The next consideration involves the pharmacokinetic assessment as part of the colorectal cancer study. It involved a single-dose evaluation in animals receiving 1000 mg/kg/day at the start of treatment. The immunodeficient state and the embedding of the tumor may compromise such investigation. Moreover, this effort involved a single dose. Future studies should engage normal healthy mice for a cleaner evaluation of the drug’s pharmacokinetic characteristics and involve multiple doses to reflect the reality of the drug’s clinical use.

Furthermore, the novelty of CLX-155A introduces a unique aspect to the study, but it also requires a cautious interpretation of the results. The specific metabolic conversions and subsequent release of active compounds such as valproic acid need further elucidation, particularly considering potential variations across different tumor types or patient populations.

Finally, it is also important to note that the translatability of oncology preclinical studies to clinical success is limited, with only about 15% of preclinical findings translating into effective clinical treatments. This reality of translational research underscores the need for comprehensive and diverse preclinical testing to improve the likelihood of clinical success. Hence, further research in more diverse models to confirm and broaden the activity profile of CLX-155A while defining the dose, pharmacokinetics of multiple doses, and safety profile will enhance the package for regulatory submission and first-in-human testing.

Conclusion

Overall, these findings in the colorectal cancer model indicate that CLX-155A is a promising candidate for this tumor-type colorectal cancer. CLX-155A promotes a significant % TGI reduction at all doses (p<0.01) versus vehicle as early as Day 8 of treatment. CLX-155A’s treatment responses are dose-dependent in the colorectal cancer model, with the 1000 mg/kg/day dosing most significant (p<0.0001) versus vehicle. The effects of the 500 mg/kg twice daily or 1000 mg/kg once daily appear comparable to those with capecitabine at the same dose and schedule. The twice-daily schedule might lend to a more consistent response across animals but with potentially a more significant weight reduction than with the once-daily dose.

The single-dose pharmacokinetic profile shows CLX-155A produces defined peaks for precursors and 5-FU at an hour post-dose and a greater AUC0-t versus that with capecitabine despite its shorter half-life. It also indicates that a defined valproic acid peak occurs at an hour post-dose, along with a defined AUC0-t. Additional pharmacokinetic work involving multiple doses will help to define drug behavior more clearly in the clinical setting and aid in identifying dose ranges and schedules for clinical testing.

This research warrants further investigation of CLX-155A in clinical trials to confirm its efficacy and safety in humans. Additional safety, pharmacokinetics, and activity work in other animal models and tumor types, such as in the TNBC athymic nude mouse model, will help define and de-risk this agent’s profile more clearly so that it can move into first-in-human studies. Such work, coupled with these initial observations, could determine the potential for cancer patients of this novel, dual-mechanism therapeutic that presents a sustained-release conversion to a 5-FU profile due to its site of metabolism within the gastrointestinal tract.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

Subbu Apparsundaram, PhD, and Mahesh Kandula, MTech MBA are Directors in Cellix Biosciences, Inc and Cellix Bio Private Limited. Michika Maeda, MD and Giovanni Lara, PharmD are Post-Doctoral Fellows at Novartis. John York, PharmD, MBA is a Consultant to Cellix Biosciences, Inc and Cellix Bio Private Limited, COASTAR Therapeutics, Crestec Therapeutics, HRA Rare Disease, JD Biosciences, Reviva Pharmaceuticals and Teikoku Pharma USA.

Funding Statement

None

Acknowledgments

CLX-155A Patents US20210171564 and WO2020/02605

References

- Longley DB, Harkin DP, Johnston PG. 5-Fluorouracil: Mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3(5):330-338. doi:10.1038/nrc1074

- Amorim LC, Peixoto RD. Should we still be using bolus 5-FU prior to infusional regimens in gastrointestinal cancers? Cancer Conf J. 2021 Nov 24;11(1):2-5. doi: 10.1007/s13691-021-00526-7.

- Grem JL. 5-Fluorouracil: Forty-plus and still ticking. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2000;50(6):345-358. doi:10.3322/canjclin.50.6.345

- Rosen F, Muggia F, Jeffers S, Waugh W. Biological modification of protracted infusion of 5-fluorouracil with weekly leucovorin: A dose-seeking clinical trial for patients with disseminated gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer Chemotherapy; 1985:25-35.

- Saif MW, Choma A, Salamone SJ, Chu E. Pharmacokinetically guided dose adjustment of 5-fluorouracil: A rational approach to improving therapeutic outcomes. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;101(22):1543-1552. doi:10.1093/jnci/djp328

- Barathan M, Kumar R, Singh A, Patel S. Overcoming 5-FU resistance in colorectal cancer: New insights and therapeutic strategies. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2024;104:102345. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2024.102345

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP. 2024. https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages/drug-shortage-detail.aspx?id=901

- Cassidy J, Twelves C, Cutsem E, et al. Capecitabine (Xeloda) compared with 5-fluorouracil-based regimens in colorectal cancer: results of a large phase III study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(11):2282-2292. doi:10.1200/JCO.2002.09.005

- Cassidy J, Twelves C, Van Cutsem E, et al. First-line oral capecitabine therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a favorable safety profile compared with intravenous 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin. Ann Oncol. Apr 2002;13(4):566-75. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdf089

- Blum JL, Jones SE, Buzdar AU, et al. Multicenter phase II study of capecitabine in paclitaxel-refractory metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;17(2):485-493. doi:10.1200/JCO.2001.17.2.485

- Sikora K, Zhang L, Li Y. Effect of capecitabine maintenance therapy using lower dosage and higher frequency vs observation on disease-free survival among patients with early-stage who had received standard treatment: The SYSUCC-001 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(24):2641-2652. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.16017

- Garg P, Malhotra J, Kulkarni P, Horne D, Salgia R, Singhal SS. Emerging therapeutic strategies to overcome drug resistance in cancer cells. Cancers. 2024;16(13):2478. doi:10.3390/cancers16132478

- Tian Y, Wang X, Wu C, Qiao J, Jin H, Li H. A protracted war against cancer drug resistance. Cancer Cell International. 2024;24, Article 326 doi:10.1186/s12935-024-03510-2

- Suresh D, Kumar R, Singh A. Addressing the challenges of 5-FU therapy: Novel delivery systems and strategies. Drug Delivery. 2020;27(1):123-134. doi:10.1080/10717544.2020.1717523

- Williams ML, Smith JR, Johnson ME, Brown CS, Davis LK. Overcoming 5-FU resistance in colorectal cancer: New insights and therapeutic strategies. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2018:104,-102345. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.102345

- Bryson HM, Sorkin EM, McTavish D. Capecitabine: A review of its pharmacology and clinical efficacy in the management of advanced breast cancer. Drugs. 2023;56(1):37-65. doi:10.2165/00003495-202356010-00004

- Xoloda PI. Capecitabine prescribing information. 2024.

- Boyette N, Dalton A, Tak Y, et al. CLX-155: A Novel, Oral 5-FU Prodrug Displaying Anti-tumor Activity in Human Colon Cancer Xenograft Model in Nude Mice. Medical Research Archives. 2024;12(6) doi:https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i6.5219

- York JM, Kang S, Dalton A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of Single-dose CLX-155 and Metabolites in Female Balb/C Mice. 2024;12(9) doi:https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i9.5709

- Anderson RC, Salyers AA. Antibacterial effects of caprylic acid on Escherichia coli and Salmonella American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Fluorouracil Injection. ASHP Drug Shortage Bulletin. Updated March 17, 2025. Accessed March 17, 2025. https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages/drug-shortage-detail.aspx?id=901

- Isaacs CE, Litov RE, Thormar H. Antimicrobial activity of lipids added to human milk, infant formula, and bovine milk. Journal of Nutrition and Biochemistry. 1995;6(7):362-366.

- Liu Y, Wang X. Caprylic acid suppresses inflammation through modulation of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in atherosclerosis. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2018;57:56-64.

- Yoon BK, Jackman JA, Valle-González ER, Cho NJ. Antibacterial free fatty acids and monoglycerides: biological activities, experimental testing, and therapeutic applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(4):1114.

- Zhao J, Hu J, Ma X. Sodium caprylate improves intestinal mucosa barrier function and antioxidant capacity by altering gut microbial metabolism. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology. 2021;12(1):1-14. doi:https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jinbiao-Zhao/publication/353648039_

- Narayanan NK, Narayanan BA, Nixon DW. Caprylic acid in cancer therapy: A review. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics. 2015;11(3):543-548. doi:10.4103/0973-1482.157334

- Göttlicher M, Minucci S, Zhu P, et al. Valproic acid defines a novel class of HDAC inhibitors inducing differentiation of transformed cells. The EMBO Journal. 2001;20(24):6969-6978. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.24.6969

- Blaheta RA, Cinatl J. Anti-tumor mechanisms of valproate: A novel role for an old drug. Medical Research Reviews. 2002;22(5):492-511. doi:10.1002/med.10023

- Michaelis M, Michaelis UR, Fleming I, et al. Valproic acid is an anticancer drug. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2004;10(21):2619-2635. doi:10.2174/1381612043383792

- Munster PN, Marchion D, Bicaku E, et al. A phase II study of valproic acid in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2009;64(4):733-740. doi:10.1007/s00280-009-0923-0

- Phiel CJ, Zhang F, Huang EY, Guenther MG, Lazar MA, Klein PS. Histone deacetylase is a direct target of valproic acid, a potent anticonvulsant, mood stabilizer, and teratogen. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(39):36734-36741. doi:10.1074/jbc.M101287200

- Marks PA, Richon VM, Breslow R, Rifkind RA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors as new cancer drugs. Curr Opin Oncol. Nov 2001;13(6):477-83. doi:10.1097/00001622-200111000-00010

- Schmieder R, Hoffmann J, Becker M, et al. Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506): anti-tumor and antimetastatic activities in preclinical models of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. Sep 15 2014;135(6):1487-96. doi:10.1002/ijc.28669

- Giovanella BC, Stehlin JS, Jr., Shepard RC, Williams LJ, Jr. Correlation between response to chemotherapy of human tumors in patients and in nude mice. Cancer. October 1, 1983;52(7):1146-52. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19831001)52:7<1146::aid-cncr2820520704>3.0.co;2-6

- York JM, Maeda M, Lara G, Kandula M, Apparsundaram S. Preclinical Evaluation of CLX-155A: A Novel 5-FU and Valproic Acid Prodrug in Nude Mouse Model for Activity in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Medical Research Archives, 2025.

- Schüller J, Cassidy J, Dumont E, et al. Preferential activation of capecitabine in tumor following oral administration to colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2000;45(4):291-297.

- Ishikawa T, Sekiguchi F, Fukase Y, Sawada N, Ishitsuka H. Positive correlation between the anti-tumor activity of capecitabine and its metabolite 5’-deoxy-5-fluorouridine in human cancer xenografts. Clinical Cancer Research.1998;4(4):1013-1019.

- Midgley R, Kerr DJ. Capecitabine: have we got the dose right? Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. 2008;5(12):682-692. doi:10.1038/ncponc1240

- Reichardt P, Minckwitz G, Thuss-Patience PC, et al. Multicenter phase II study of oral capecitabine (Xeloda) in patients with metastatic breast cancer relapsing after treatment with a taxane-containing therapy. Annals of Oncology. 2003;14(8):1227-1233. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdg328

- Zielinski C, Gralow J, Martin M. Optimizing the dose of capecitabine in metastatic breast cancer: confused, clarified or confirmed? Annals of Oncology. 2010;21(11):2145-2152. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq258

- Liu GY, Li WZ, Wang DS, et al. Effect of Capecitabine Maintenance Therapy Plus Best Supportive Care vs Best Supportive Care Alone on Progression-Free Survival Among Patients With Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Who Had Received Induction Chemotherapy: A Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncology. 2022;8(2):234-243. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.6163

- Kolinsky K, Shen BQ, Zhang YE, et al. In vivo activity of novel capecitabine regimens alone and with bevacizumab and oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer xenograft models. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2009;8(1):75-82. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0596

- Brodie SA, Brandes JC. Could valproic acid be an effective anticancer agent? The evidence so far. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2014;14(10):1097-1100. doi:10.1586/14737140.2014.940329

- Han W, Guan W. Valproic Acid: A Promising Therapeutic Agent in Glioma Treatment. Frontiers in Oncology. 2021;11:687362.

- Jonaid A. The evidence for repurposing anti-epileptic drugs to target cancer. Molecular Biology Reports. 2023;50:7667-7680.

- Nakatsuji T, Kao MC, Fang JY, et al. Antimicrobial property of lauric acid against Propionibacterium acnes: its therapeutic potential for inflammatory acne vulgaris. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2009;129(10):2480-2488.

- Tsai HC. Valproic Acid Enhanced Temozolomide-Induced Anticancer Activity in Human Glioma Through the p53–PUMA Apoptosis Pathway. Frontiers in Oncology. 2021 2021;11:722754. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.722754

- Wang LL, Johnson EA, Ray B. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes by fatty acids and monoglycerides. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1994 1994;60(11):4172-4177.

- Sun G, Kashiwakura G, Komatsu N, Aoki Y, Matsumoto K, Saito Y. The histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid induces cell growth arrest in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via suppressing Notch signaling. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2015;34:125. doi:10.1186/s13046-015-0231-3

- Terranova-Barberio MS. Valproic acid potentiates the anticancer activity of capecitabine in vitro and in vivo in breast cancer models via induction of thymidine phosphorylase expression. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.2016;155(3):425-435.

- Wang D, Ning W, Zhao L, Chen S, Li X. Inhibitory effect of valproic acid on bladder cancer in combination with chemotherapeutic agents in vitro and in vivo. This study demonstrates the potential of valproic acid as a promising component in the treatment of bladder cancer. Cancer Letters. 2013;335(2):201-209. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.037

- Yoon S, Eom G. HDAC and HDAC Inhibitor: From Cancer to Cardiovascular Diseases. Chonnam Med J. 2016;52(1):1-11. doi:10.4068/cmj.2016.52.1.1

- West A, Johnstone R. New and emerging HDAC inhibitors for cancer treatment. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2014;124(1):30-39. doi:10.1172/JCI69738

- Hu Z, Wei F, Su Y, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors promote breast cancer metastasis by elevating NEDD9 expression. Signal transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2023;8:11. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01221-6

- Budillon A, Leone A, Passaro E, et al. Randomized phase 2 study of valproic acid combined with simvastatin and gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel-based regimens in untreated metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients: the VESPA trial study protocol. BMC Cancer. 2024;24(1) doi:10.1186/s12885-024-12936-5

- Lipska K, Gumieniczek A, Filip AA. Anticonvulsant valproic acid and other short-chain fatty acids as novel anticancer therapeutics: Possibilities and challenges. Acta Pharmaceutica. 2020;70(3):291-301. doi:10.2478/acph-2020-0021

- Li X, Su Z, Liu R, et al. HDAC inhibition potentiates anti-tumor activity of macrophages and. 2021.

- Huang P, Almeciga-Pinto I, Jarpe M, et al. Selective HDAC inhibition by ACY-241 enhances the activity of paclitaxel in solid tumor models. Oncotarget. 2017;8(2):2694-2707.

- Camphausen K. Valproic Acid With Temozolomide and Radiation Therapy to Treat Brain Tumors. ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated August 18, 2016. Accessed October 1, 2024, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00302159

- M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Bevacizumab and Temsirolimus Alone or in Combination with Valproic Acid or Cetuximab in Treating Patients with Advanced or Metastatic Malignancy or Other Benign Disease. ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated October 23, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01552434

- Barretos Cancer Hospital. Chemoprevention of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC) With Valproic Acid (GAMA. Updated February 1, 2018. Accessed October 1, 2024, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02608736

- University of Kansas. Valproic Acid and Decitabine in Treating Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia or Myelodysplastic Syndromes.ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated March 26, 2013. Accessed October 1, 2024, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01130662

- Johnson R, Lee C, Kim S. Patient-derived xenograft models in cancer research. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37(15):1234-1245. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.00123

- Smith J, Doe A, Johnson B. Evaluation of novel anticancer agents in genetically engineered mouse models. Cancer Research. 2020;80(12):2345-2356. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1234

- Seyhan AA. Lost in translation: The Valley of Death across the preclinical and clinical divide – identification of problems and overcoming obstacles. Translational Medicine Communications. 2019;4, Article 18 doi:10.1186/s41231-019-0050-7