Metadichol: A Novel Multi-Target mTOR Modulator

Beyond Rapamycin: Metadichol Represents a New Class of Multi-Target mTOR Modulators

P.R. Raghavan 1

- Nanorx Inc., PO Box 131 Chappaqua, NY 10514, USA. Email: [email protected]

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 September 2025

CITATION: Raghavan, PR., 2025. Beyond Rapamycin: Metadichol Represents a New Class of Multi-Target mTOR Modulators. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(9). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.0000

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.0000

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Aim: The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway represents a critical regulatory hub controlling cellular growth, metabolism, and survival, with its dysregulation implicated in numerous pathological conditions, including cancer, metabolic disorders, and aging. While conventional mTOR inhibitors such as rapamycin and its analogs have shown therapeutic promise, their clinical efficacy is often limited by incomplete pathway inhibition, feedback activation of compensatory pathways, and significant side effects. This study aimed to investigate the multi-target modulatory effects of metadichol, a nanoemulsion of long-chain alcohols, on the mTOR signaling network and its downstream effectors, with particular focus on DNA damage inducible transcript 4 (DDIT4) and ribosomal protein S6 kinase B1 (p70S6K) regulation across diverse cellular contexts.

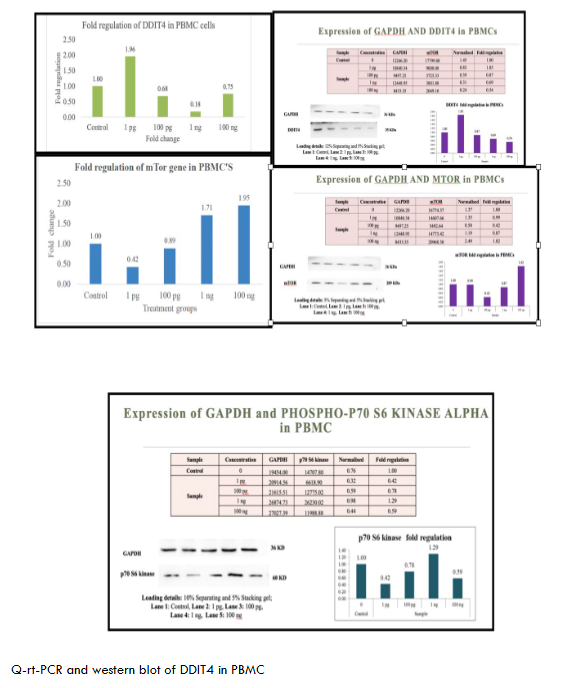

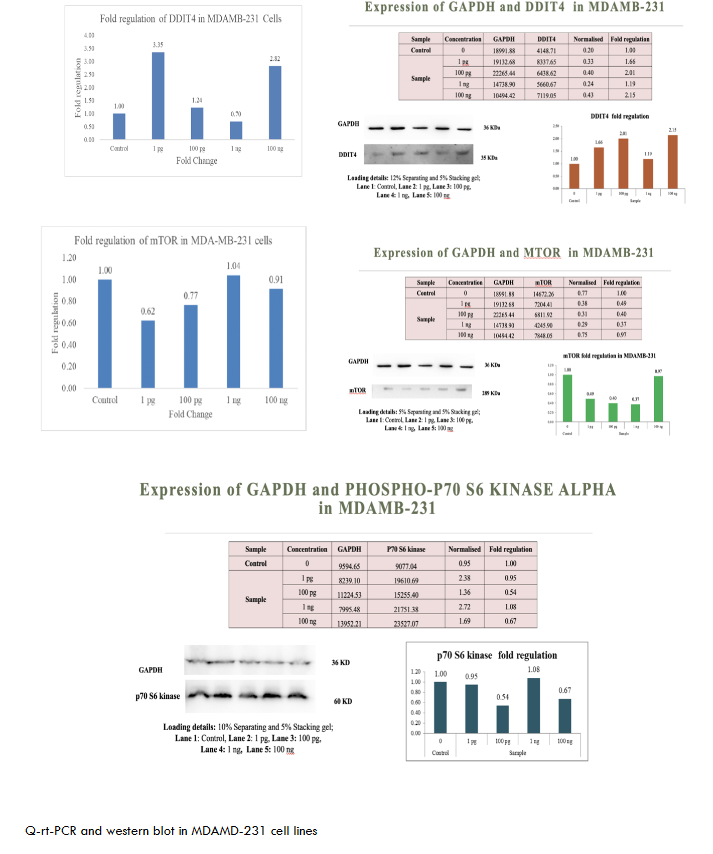

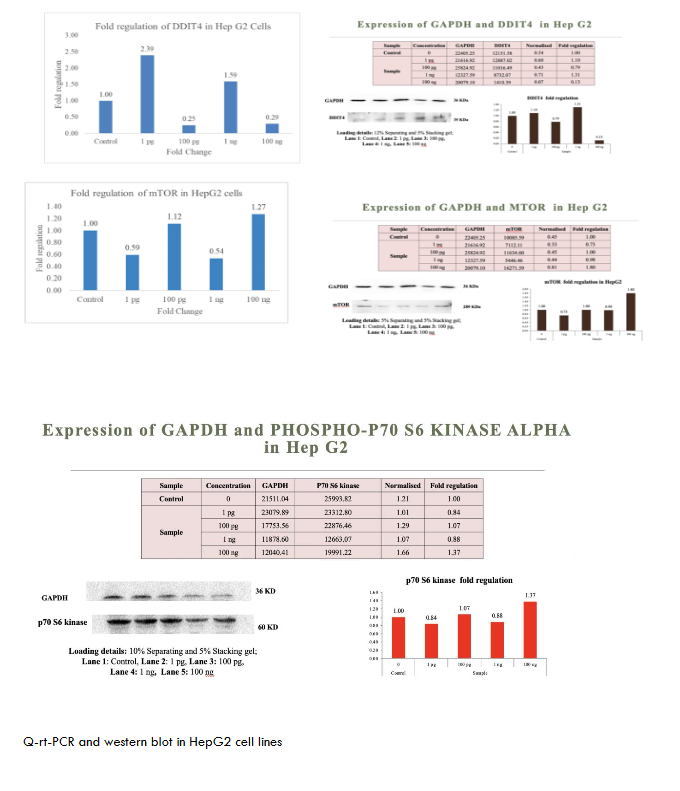

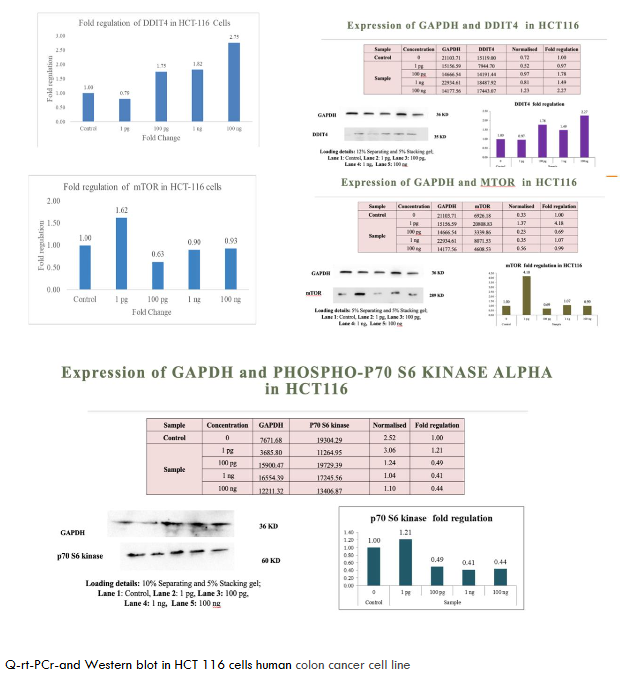

Scope: The scope of this investigation encompassed comprehensive molecular analysis of metadichol’s effects on key components of the mTOR signaling cascade in both immune cells (peripheral blood mononuclear cells, PBMCs) and multiple cancer cell lines representing different tissue origins (U87 glioblastoma, A549 lung adenocarcinoma, MDA-MB-231 breast cancer, HCT116 colorectal cancer, and HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma). The study employed quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis to evaluate gene expression changes and Western blot techniques to assess protein-level modifications. Concentration-response relationships were established across a range from 1 pg/mL to 100 ng/mL to determine the minimal effective dose and characterize dose-dependent effects.

Methods: Primary human PBMCs were isolated using density gradient centrifugation and treated with various concentrations of metadichol for 24 hours. Cancer cell lines were cultured under standard conditions and subjected to identical treatment protocols. RNA extraction was performed using TRIzol methodology, followed by cDNA synthesis and qRT-PCR analysis using specific primers for mTOR, DDIT4, and p70S6K genes. Protein expression analysis was conducted using Western blot techniques with specific antibodies. Gene expression changes were calculated using the ΔΔCt method with β-actin as the housekeeping gene reference.

Key Findings: Metadichol demonstrated remarkable potency in modulating mTOR signaling components at concentrations as low as 1 pg/mL, representing activity levels several orders of magnitude lower than conventional mTOR inhibitors. The compound consistently upregulated DDIT4 expression across all tested cell types, with concurrent downregulation of both mTOR and p70S6K expression. In PBMCs, metadichol induced significant DDIT4 upregulation while suppressing mTOR expression, with p70S6K showing delayed dose-dependent inhibition at higher concentrations (100 ng/mL). Cancer cell lines exhibited robust responses with DDIT4 upregulation accompanied by substantial downregulation of both mTOR and p70S6K across multiple concentrations. Notably, the hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2 showed resistance to p70S6K inhibition despite effective mTOR suppression, suggesting cell-type-specific response patterns and potential alternative pathway activation. involvement of high-affinity receptor-mediated mechanisms or amplification through secondary messenger systems.

Conclusions: Metadichol represents a paradigm shift in mTOR pathway modulation, demonstrating unprecedented potency and multi-target activity that distinguishes it from conventional rapamycin-based inhibitors. The compound’s ability to coordinately regulate DDIT4, mTOR, and p70S6K at picomolar concentrations suggests novel mechanisms of action that warrant further investigation. The unique pharmacological profile of metadichol may herald the development of next-generation mTOR modulators with enhanced efficacy and improved safety characteristics for treating cancer, metabolic disorders, and age-related diseases.

Keywords:

mTOR signaling, DDIT4, p70S6K, metadichol, nanoemulsion, cancer therapy, immunomodulation, rapamycin alternative, multi-target therapy, picomolar.

Abbreviations

- PBMC: Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- mTOR: Mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase

- RPS6KB1: Ribosomal protein S6 kinase B1 (p70S6 kinase)

- DDIT4: DNA damage inducible transcript 4

- DEPTOR: DEP domain containing mTOR interacting protein

- mLST8: mTOR associated protein, LST8 homolog

- IGF1: Insulin like growth factor 1

- TSC1: TSC complex subunit 1

- TSC2: TSC complex subunit 2

- SIRTs: Sirtuins

- PPARα: Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha

- TLRs: Toll like receptors

- IRAK4: Interleukin 1 receptor associated kinase 4

- MYD88: MYD88 innate immune signal transduction adaptor

- TRAF6: TNF receptor associated factor 6

- CLOCK: Clock circadian regulator

- PER1: Period circadian regulator 1

- CRY1: Cryptochrome circadian regulator 1

- BMAL1: Basic helix-loop-helix ARNT like 1

- AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase

- AKT: Protein kinase B

- KLF: Kruppel like factor

- mTORC1: Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1

- mTORC2: Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2

- NAD+: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- LPS: Lipopolysaccharide

- REDD1: Regulated in development and DNA damage responses 1

- PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases

- PROTOR: Protein observed with Rictor-1

- PRAS40: Proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa

- GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- VDR: Vitamin D receptor

Introduction

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) and its key downstream effector, ribosomal protein S6 kinase B1 (p70S6K), represent central regulatory nodes in cellular signaling networks that orchestrate fundamental biological processes essential for life. As evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine protein kinases, mTOR belongs to the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-related kinase family and functions as a master regulator integrating diverse environmental and intracellular signals to precisely control cellular growth, metabolism, and survival. The profound impact of mTOR signaling on cellular homeostasis is underscored by its dysregulation in an extensive spectrum of human diseases, ranging from metabolic disorders and neurodegeneration to cancer and aging-related pathologies.

Historical Perspective and Discovery

The discovery of mTOR traces back to 1970 when rapamycin was first isolated from the soil bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus on the remote Easter Island (Rapa Nui), initially recognized for its potent antifungal properties. Subsequent structural elucidation revealed rapamycin’s unique architecture, characterized by 14-16 membered lactone rings and reduced saccharide substituents that confer its distinctive biological activity. The physiological characterization of rapamycin unveiled remarkable immunosuppressive properties that revolutionized organ transplantation medicine by effectively curtailing organ rejection and inhibiting T-cell mitogenesis. The identification of rapamycin’s cellular target led to the discovery of mTOR (initially termed FRAP1, FKBP12-rapamycin associated protein 1), establishing the foundation for understanding this critical signaling pathway.

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) Complex Architecture and Functional Organization

Mechanistically, mTOR exhibits dual kinase activity, capable of phosphorylating both serine/threonine and tyrosine residues, and has been classified within the PI3K family due to the structural similarity of its catalytic domain with lipid kinases. This evolutionary conservation underscores mTOR’s fundamental importance across species, from yeast to mammals, highlighting its essential role in coordinating cellular responses to environmental changes.

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) functions through two distinct multiprotein complexes that exhibit unique regulatory mechanisms and downstream effects. mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), the rapamycin-sensitive complex, comprises mTOR as the catalytic subunit along with regulatory associated protein of mTOR (Raptor), mammalian lethal with SEC13 protein 8 (mLST8), DEP domain-containing mTOR-interacting protein (DEPTOR), and proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa (PRAS40). The primary function of mTORC1 centers on promoting anabolic processes essential for cellular growth, including protein synthesis, ribosome biogenesis, lipid biosynthesis, and nucleotide synthesis. Simultaneously, mTORC1 exerts inhibitory control over catabolic processes, particularly autophagy, which serves as a crucial cellular quality control mechanism for degrading damaged organelles and misfolded proteins.

In contrast, mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2), the rapamycin-insensitive complex, consists of mTOR, mLST8, rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (Rictor), mammalian stress-activated protein kinase-interacting protein 1 (mSIN1), proline-rich protein 5 (Protor-1), and DEPTOR. Unlike mTORC1, mTORC2 is not directly inhibited by acute rapamycin treatment, although prolonged exposure may affect its function. mTORC2 primarily regulates cell survival, cytoskeletal organization, and the activation of Akt, a serine/threonine kinase that plays pivotal roles in cellular metabolism, survival, and proliferation.

Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase B1 (p70S6K): A Critical mTORC1 Effector

Ribosomal protein S6 kinase B1 (p70S6K), also designated as RPS6KB1, represents one of the most extensively characterized downstream effectors of mTORC1 signaling. As a member of the AGC family of protein kinases, p70S6K serves as a critical mediator of mTORC1’s effects on protein synthesis and cellular growth. The mechanistic target of the rapamycin complex (mTORC1) activates p70S6K through phosphorylation at multiple regulatory sites, most notably threonine 389 (Thr389) and the threonine 421/serine 424 (Thr421/Ser424) cluster, which serve as hallmarks of mTORC1 activation.

Upon activation, p70S6K phosphorylates ribosomal protein S6 (rpS6), a component of the 40S ribosomal subunit, thereby promoting the translation of specific mRNA species encoding proteins involved in ribosome biogenesis and cellular growth. Beyond rpS6, p70S6K influences multiple aspects of mRNA translation, including initiation and elongation processes, contributing to the comprehensive regulation of protein synthesis. The phosphorylation of p70S6K at Thr389 has become widely utilized as a biomarker for mTORC1 activity and has been correlated with autophagy inhibition across various experimental contexts.

Recent investigations have revealed that p70S6K functions extend beyond simple cell size control, encompassing crucial roles in directing cellular apoptosis, metabolism, and feedback regulation of upstream signaling pathways. The kinase simultaneously influences diverse cellular processes while maintaining intricate feedback loops that modulate its own activation state and that of related signaling networks.

Upstream Regulation of mTOR Signaling

The activity of mTOR is subject to sophisticated regulation by a complex network of upstream signals that ensure cellular growth and metabolism are appropriately coordinated with environmental conditions. These regulatory inputs include growth factors, hormones, nutrients, energy status, and various stress signals that collectively determine mTORC1 activation state.

Growth factors, particularly insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), represent primary activators of the mTOR pathway through stimulation of the PI3K/Akt signaling cascade. Upon growth factor binding to receptor tyrosine kinases, PI3K generates phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), which recruits and activates Akt through phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) and mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation. Activated Akt subsequently phosphorylates and inactivates the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC1/TSC2), a critical negative regulator of mTORC1, thereby promoting mTORC1 activation.

Amino acid availability, particularly leucine and arginine, provides essential signals for mTORC1 activation through mechanisms involving lysosomal localization and Rag GTPase activation. The Rag GTPases function as molecular switches that mediate the recruitment of mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface, where it encounters its activators and substrates. This lysosomal translocation represents a prerequisite for amino acid-dependent mTORC1 activation and highlights the spatial organization of mTOR signaling.

Cellular energy status, monitored by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), provides another critical regulatory input to mTOR signaling. AMPK functions as a cellular energy sensor that becomes activated under conditions of energy depletion (characterized by elevated AMP:ATP ratios). Upon activation, AMPK directly phosphorylates and activates TSC2, thereby inhibiting mTORC1 and ensuring that energy-consuming anabolic processes are curtailed during periods of metabolic stress.

DNA Damage Inducible Transcript 4 (DDIT4): A Stress-Responsive mTOR Regulator

DNA damage inducible transcript 4 (DDIT4), also known as regulated in development and DNA damage response 1 (REDD1), represents a critical stress-responsive protein that serves as a physiological inhibitor of mTORC1 signaling. Initially identified in 2002 by independent research groups, DDIT4 was discovered as a gene induced by hypoxia, DNA damage, and various cellular stressors. The protein encoded by the DDIT4 gene is located on human chromosome 10q24.33, functions as a molecular switch that coordinates cellular responses to environmental challenges.

DNA damage inducible transcript 4 (DDIT4) exerts its inhibitory effects on mTORC1 through a sophisticated mechanism involving the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Under normal conditions, growth factor-activated Akt phosphorylates TSC2 at serine 939 and serine 981, promoting the association of TSC2 with 14-3-3 proteins and effectively sequestering the TSC1/TSC2 complex in an inactive state. This inactivation allows Rheb (Ras homolog enriched in brain) GTPase to accumulate in its GTP-bound active form, thereby stimulating mTORC1 kinase activity.

Upon cellular stress, DDIT4 expression is rapidly induced through multiple transcriptional mechanisms involving hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), p53, and other stress-responsive transcription factors. The accumulated DDIT4 protein functions as a competitive inhibitor of 14-3-3 proteins, effectively sequestering these regulatory proteins and preventing their interaction with phosphorylated TSC2. This sequestration allows the TSC1/TSC2 complex to reassemble in its active configuration, where TSC2 functions as a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) toward Rheb, promoting GTP hydrolysis and subsequent mTORC1 inactivation.

The DDIT4-mediated regulation of mTORC1 represents a fundamental cellular adaptation mechanism that allows cells to rapidly downregulate energy-consuming anabolic processes in response to stress conditions such as hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, or DNA damage. This regulatory circuit ensures cellular survival during adverse conditions by promoting a shift from growth-promoting to stress-resistance programs.

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) Signaling in Cancer: Dysregulation and Therapeutic Implications

The mTOR signaling pathway is frequently dysregulated in human cancers, contributing significantly to uncontrolled cell growth, proliferation, survival, and metastasis. Hyperactivation of mTORC1 occurs in a substantial proportion of human malignancies through diverse mechanisms, including mutations in upstream regulatory components, oncogene amplification, and tumor suppressor gene inactivation.

Genetic alterations affecting PI3K, Akt, PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), or TSC1/TSC2 represent common mechanisms underlying mTORC1 hyperactivation in cancer. These mutations disrupt normal regulatory circuits that control mTORC1 activity, resulting in constitutive pathway activation that drives malignant transformation and progression. Additionally, overexpression of growth factors or their receptors can stimulate sustained PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling, contributing to oncogenic transformation.

The hyperactivation of mTORC1 in cancer cells promotes multiple hallmarks of malignancy, including enhanced protein synthesis, accelerated cell growth, resistance to apoptosis, increased angiogenesis, and metabolic reprogramming. These effects collectively contribute to tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance, establishing mTOR as an attractive target for cancer intervention.

Current mTOR Inhibitors: Achievements and Limitations

The recognition of mTOR’s central role in cancer biology has spurred extensive efforts to develop therapeutic inhibitors targeting this pathway. Rapamycin and its analogs (rapalogs), including everolimus and temsirolimus, represent the first generation of mTOR inhibitors to achieve clinical approval. These compounds function by forming a complex with the intracellular protein FKBP12, which then binds to and allosterically inhibits mTORC1.

| Inhibitor | Potency (Effective Concentration) | Mechanism of mTOR Inhibition | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapamycin | 1–100 nM (~0.91–91 ng/mL) | Forms FKBP12 complex, allosterically inhibits mTORC1; prolonged use may affect mTORC2 | Cancer (renal cell carcinoma, breast cancer); immunosuppression; aging (extends lifespan in preclinical models) | Immunosuppression, glucose intolerance, incomplete mTORC1 inhibition |

| Everolimus | 1–20 nM (~1–20 ng/mL) | FKBP12-mediated mTORC1 inhibition; similar to rapamycin | Cancer (breast cancer, RCC); immunosuppression | Rash, stomatitis, metabolic disturbances |

| Temsirolimus | Nanomolar range (comparable to sirolimus) | FKBP12-mediated mTORC1 inhibition | Cancer (RCC, leukemia, endometrial) | Limited efficacy in some cancers, side effects similar to rapamycin |

| Metformin | Micromolar range (e.g., 100–1000 μM) | Activates AMPK, inhibits mTORC1 via TSC2; may upregulate DDIT4 | Diabetes (insulin sensitivity); cancer (reduces incidence); aging (extends lifespan in preclinical models) | Less potent, partial mTOR inhibition, gastrointestinal side effects |

| Resveratrol | Micromolar range (e.g., 10–100 μM) | Activates AMPK/SIRT1, inhibits mTORC1; multiple targets (e.g., PKC, MAPK3) | Obesity (reduces fat accumulation); cancer (inhibits proliferation); limited aging benefits | Lower potency, less effective in lifespan extension |

Despite initial promise, first-generation mTOR inhibitors have demonstrated several significant limitations that restrict their clinical efficacy. Rapamycin and rapalogs provide incomplete inhibition of mTORC1 signaling, failing to suppress all downstream effectors uniformly. Moreover, chronic mTORC1 inhibition can paradoxically activate compensatory pathways, including PI3K/Akt signaling, through relief of negative feedback loops. This compensation can limit therapeutic effectiveness and contribute to the development of drug resistance.

The clinical experience with rapalogs has revealed additional challenges, including variable efficacy across different cancer types, development of resistance mechanisms, and significant side effects such as immunosuppression, metabolic disturbances, and impaired wound healing. These limitations have motivated the development of second-generation mTOR inhibitors that target both mTORC1 and mTORC2, as well as dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors designed to prevent compensatory pathway activation.

Metadichol: A Novel Approach to mTOR Modulation

Metadichol is a nanoemulsion formulation derived from long-chain saturated primary alcohols (predominantly C28, with C26 and C30 components), originally isolated from sugarcane. This novel compound has demonstrated remarkable pleiotropic biological activities through comprehensive modulation of multiple cellular signaling networks: nuclear receptor, sirtuin, TLR, KLF, and circadian regulatory, vitamin C, GDF11, Klotho, and FOXO1 networks.

Systems Biology Perspective

The networks activated by Metadichol suggest a systems-level approach to transcriptional modulation. Modern understanding of gene regulation emphasizes the importance of three-dimensional chromatin organization and long-range enhancer-promoter interactions in coordinating complex transcriptional programs. The comprehensive activation of multiple transcriptional networks by Metadichol may facilitate coordinated chromatin remodeling and enhanced transcriptional synergy across the FOX gene family.

Research Rationale and Objectives

Given Metadichol’s unprecedented ability to activate multiple transcriptional regulatory networks known to interact with FOX transcription factors, we hypothesized that Metadichol treatment would result in coordinated modulation of SOX family gene expression. Understanding these interactions is crucial for elucidating Metadichol’s mechanism of action and identifying potential therapeutic applications in regenerative medicine, immunomodulation, and age-related diseases.

The present study aimed to (1) comprehensively characterize the dose-dependent effects of Metadichol on all FOX family genes in human PBMCs; (2) identify optimal concentrations for maximal transcriptional effects; (3) analyze the relationship between FOX gene regulation and Metadichol’s known effects on nuclear receptors, sirtuins, TLRs, and circadian networks; and (4) provide mechanistic insights into the synergistic transcriptional networks underlying Metadichol’s pleiotropic biological activities.

Research Rationale and Objectives

The limitations of current mTOR inhibitors, combined with the growing understanding of mTOR signaling complexity, highlight the need for novel therapeutic approaches that can effectively modulate this pathway while minimizing adverse effects. The present investigation was designed to comprehensively evaluate the effects of metadichol on key components of the mTOR signaling network, with particular emphasis on DDIT4 upregulation and its consequences for mTORC1 and p70S6K activity.

The selection of DDIT4 as a primary endpoint reflects its physiological role as an endogenous mTORC1 inhibitor and its potential as a therapeutic target for diseases characterized by mTOR hyperactivation. By investigating metadichol’s ability to upregulate DDIT4 expression, this study aims to elucidate a potentially novel mechanism for achieving mTOR pathway modulation that leverages endogenous regulatory circuits rather than relying solely on direct enzyme inhibition.

The inclusion of both immune cells (PBMCs) and multiple cancer cell lines in the experimental design reflects the diverse therapeutic applications envisioned for mTOR modulators. PBMCs serve as a model for investigating immunomodulatory effects, while the panel of cancer cell lines representing different tissue origins allows for assessment of therapeutic potential across various malignancy types. The concentration range selected for this investigation (1 pg/mL to 100 ng/mL) was designed to explore metadichol’s activity across several orders of magnitude, with particular attention to identifying minimal effective concentrations that might translate to improved safety profiles in clinical applications. The remarkably low concentrations showing biological activity distinguish metadichol from conventional mTOR inhibitors and suggest unique mechanisms of action that warrant detailed investigation.

This comprehensive approach to evaluating metadichol’s effects on mTOR signaling components provides the foundation for understanding its potential as a next-generation mTOR modulator with enhanced therapeutic properties and reduced limitations compared to current inhibitors. The findings from this investigation may inform the development of novel therapeutic strategies for mTOR-driven diseases and contribute to the advancement of precision medicine approaches targeting this critical signaling pathway.

Limitations and Side Effects

In vitro, the effective concentration of rapamycin (table 1) is typically 1–100 nM approximately 0.91–91 ng/ml, given its molecular weight of ~914 g/mol. Everolimus: A rapamycin analog that inhibits mTORC1 and decreases P70S6K activity. Although effective at 1–20 nM ~1–20 ng/ml, despite their therapeutic potential, mTOR inhibitors can cause significant side effects, including metabolic disturbances and skin reactions. The management of these adverse effects is crucial for maintaining patient quality of life and treatment adherence.

Ongoing research aims to optimize the use of mTOR inhibitors, including identifying biomarkers for patient selection and exploring combination therapies to increase their efficacy and overcome resistance, mTOR and p70S6K are central regulators of cellular processes, and their dysregulation plays a significant role in a broad array of human diseases. The development of effective therapeutic strategies targeting this pathway requires a deeper understanding of the complex regulatory mechanisms governing mTOR signaling. There is a need to develop more specific and compelling mTOR modulators with improved safety profiles. The development of next generation mTOR inhibitors with enhanced specificity and potency and reduced side effects is essential for improving therapeutic efficacy and patient safety. Investigating the interplay between mTOR signaling and other pathways:

Our results revealed that metadichol, a nanoemulsion of long-chain lipid alcohols, the major constituent of which is C28 straight-chain alcohol 85%, modulates the mTOR and P70S6K pathways at 1 pg/ml 10⁻¹² g/ml. This is an extremely low dose of metadichol, which is a nontoxic molecule derived from food sources, and we explored its ability to regulate mTOR, DDIT4, and cancer cells, as evidenced by Q-RT‒PCR techniques, and p79S6 kinase activity in PBMCs, as evidenced by Western blot techniques.

Experimental

All work was conceived, planned and supervised by the author and outsourced to the service provider Skanda Life Sciences Bangalore, India. A549, U-87 MG, HepG2, HCT116 and MDAMB-231 cells were obtained from ATCC USA. Primary antibodies were purchased from E-lab Science, Maryland, USA. The primers used were obtained from Eurofins Bangalore, India. All other molecular biology reagents were obtained from Sigma Aldrich, Bangalore, India.

Preparation of the blood sample:

Fresh human blood was collected in EDTA-containing tubes, and then fresh blood was diluted with PBS at a 1:1 ratio and mixed by inverting the tube.

Isolation of Mononuclear Cells

In the 15 ml centrifuge tube, 5 ml of Histopaque-1077 was added such that 5 ml of prepared blood was slowly layered on the histopaque from the edge of the tube without disturbing the histopaque layer. Then, the tubes were centrifuged at 400 X g for exactly 30 min at room temperature with brake-off settings. After centrifugation, the upper layer was discarded with a Pasteur pipette without disturbing the interphase layer. The interphase layer was carefully transferred to a clean centrifuge tube. The cells will be washed with 1X PBS and again centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 mins. 2X. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was collected in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were counted, and their viability was checked with a hemocytometer. The cell count was adjusted to 10×106 cells/2 ml. Two milliliters of cell suspension was added to each dish in P35 dishes. The cells were then treated with various concentrations of the test sample. After incubation, the cells were harvested for protein isolation via RIPA buffer.

The cells were maintained at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml, seeded into 6-well plates and incubated for 24 hrs at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 24 h of seeding, the media was carefully removed, and the cells were treated with the test samples the concentration was selected on the basis of the MTT experiment and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator.

| Cell lines | Sample name | Treatment details |

|---|---|---|

| Human PBMC | Metadichol | Control |

| A549 | 1 pg/ml | |

| U-87 MG | 100 pg/ml | |

| HepG2 | 1 ng/ml | |

| HCT116 | 100 ng/ml | |

| MDA-MB-231 |

Sample Preparation and RNA Isolation

The treated cells were dissociated, rinsed with sterile 1X PBS and centrifuged. The supernatant was decanted, and 0.1 ml of TRIzol was added and gently mixed by inversion for 1 min. The samples were allowed to stand for 10 min at room temperature. To this mixture, 0.75 ml of chloroform was added per 0.1 ml of TRIzol used. The contents were vortexed for 15 seconds. The tube was allowed to stand at room temperature for 5 mins. The resulting mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The upper aqueous phase was collected in a new sterile microcentrifuge tube, to which 0.25 ml of isopropanol was added, and the mixture was gently mixed by inverting the contents for 30 seconds and then incubated at -20°C for 20 minutes. The contents were subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the RNA pellet was washed by adding 0.25 ml of 70% ethanol. The RNA mixture was subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was carefully discarded, and the pellet was air dried. The RNA pellet was then resuspended in 20 μl of DEPC-treated water. The total RNA yield was quantified via a Spectra drop Spectramax i3x, Molecular Devices, USA.

RNA Quality

RNA integrity was confirmed through spectrophotometric analysis, and all samples yielded high-quality RNA suitable for qPCR.

| Test concentrations | RNA yield ng/µl | 0 | 1 pg/ml | 100 pg/ml | 1 ng/ml | 100 ng/ml |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human PBMC’s | 503.12 | 696.88 | 692.123 | 681.84 | 644.96 | |

| A549 cells | 402.1 | 398.7 | 413.6 | 383.2 | 376 | |

| HCT116 | 421.5 | 455.4 | 392.2 | 371.2 | 478.6 | |

| MDA-MB-231 | 325.6 | 333.6 | 612.5 | 398.7 | 569.8 | |

| U-87 MG | 590.5 | 521.6 | 751.7 | 771.6 | 761.8 | |

| Hep G2 | 542.3 | 698.6 | 644.3 | 712.4 | 513.4 |

| Test concentrations | RNA yield ng/µl | 0.0 | 1 pg/ml | 100 pg/ml | 1 ng/ml | 100 ng/ml |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC | 503.1 | 696.9 | 692.1 | 681.8 | 645.0 | |

| A549 cells | 402.1 | 398.7 | 413.6 | 383.2 | 376.0 | |

| U-87 MG | 590.5 | 521.6 | 751.7 | 771.6 | 761.8 | |

| Hep G2 | 542.3 | 698.6 | 644.3 | 712.4 | 513.4 | |

| HCT116 | 421.5 | 455.4 | 392.2 | 371.2 | 478.6 | |

| MDA-MB-231 | 325.6 | 333.6 | 612.5 | 398.7 | 569.8 |

cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng of RNA via a cDNA synthesis kit from the PrimeScript RT reagent kit TAKARA with oligo dT primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction volume was set to 20 μl, and cDNA synthesis was performed at 50°C for 30 min, followed by RT inactivation at 85°C for 5 min using Applied Biosystems Veritii. The cDNA was further used for real-time PCR analysis.

Primers and qPCR analysis

The PCR mixture final volume of 20 μl contained 1.4 μl of cDNA, 10 μl of SYBR Green Master mix, and 1 μM complementary forward and reverse primers specific for the respective target genes. The reaction was carried out with enzyme activation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by a 2-step reaction with initial denaturation and an annealing-cum-extension step at 95°C for 5 seconds, annealing for 30 seconds at the appropriate respective temperature amplified for 39 cycles, followed by secondary denaturation at 95°C for 5 seconds, and 1 cycle with a melt curve capture step ranging from 65°C to 95°C for 5 seconds each. The obtained results were analyzed, and the fold change in expression or regulation was calculated.

The fold change was calculated via the following equation:

ΔΔ CT Method

The relative expression of the target gene in relation to the housekeeping gene β-actin and untreated control cells was determined via the comparative CT method. The delta CT for each treatment was calculated via the following formula:

Delta Ct = Ct target gene – Ct reference gene

To compare the individual sample from the treatment with the untreated control, the delta CT of the sample was subtracted from the control to obtain a delta delta CT.

Delta delta Ct = delta Ct treatment group – delta Ct control group

The fold change in target gene expression for each treatment was calculated via the following formula:

| Primer | Sequence | Amplicon size | Annealing temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG Forward | 186 | 60 |

| ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA reverse | |||

| mTor | ATGCTTGGAACCGGACCTG Forward | 173 | 45 |

| TCTTGACTCATCTCTCGGAGTT reverse | |||

| DDIT4 | TGAGGATGAACACTTGTGTGC forward | 109 | 60 |

| CCAACTGGCTAGGCATCAGC reverse |

SDS‒PAGE and Western Blot Procedure

Protein isolation

Total protein was isolated from 106 cells via RIPA buffer supplemented with the protease inhibitor PMSF. The cells were lysed for 30 min at 4°C with gentle inversion. The cells were subsequently centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min, after which the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. The protein concentration was determined via the Bradford method, and 25 µg of protein was mixed with 1X sample loading dye containing SDS and loaded on a gel. The proteins were separated under denaturing conditions using Tris-glycine running buffer.

| Protein Markers | Separating Gel Percentage | Stacking Gel Percentage | Antibody catalog no. with dilution details | Exposure Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | 10% | 5% | Elab science -AB-20072 1:1000 | 5 secs. |

| Phospho-p70 S6 kinase alpha Ser418 | 10% | 5% | Elab science—AB-21476 1:1500 | 20-30 secs |

| DDIT4 | 12% | 5% | E-AB-90739 1:1000 | 60-100 secs |

| mTor | 5% | 5% | E-AB-70304 1:1000 | 60-100 secs |

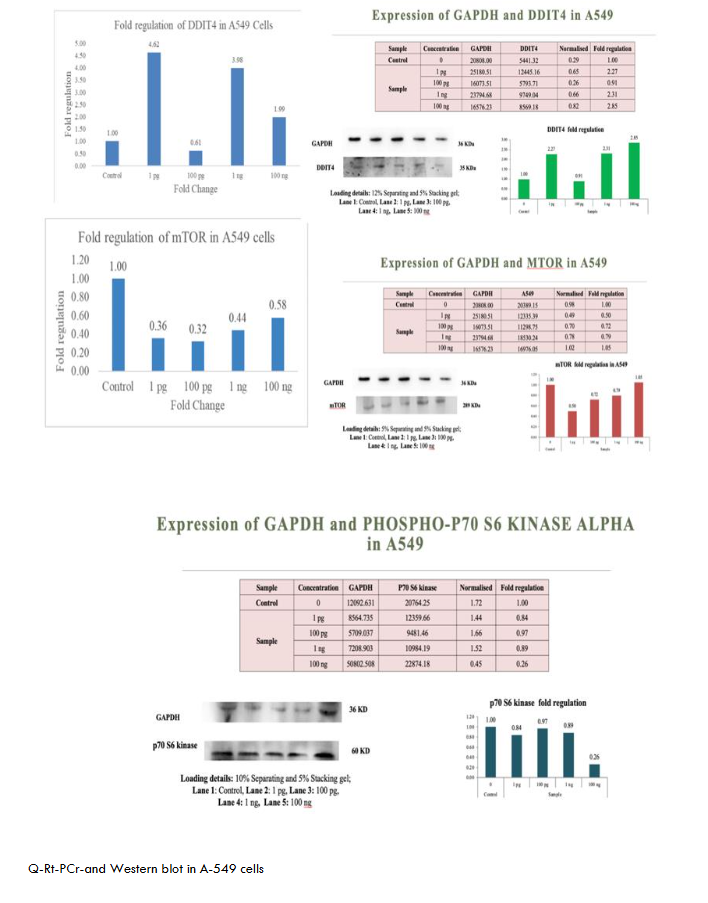

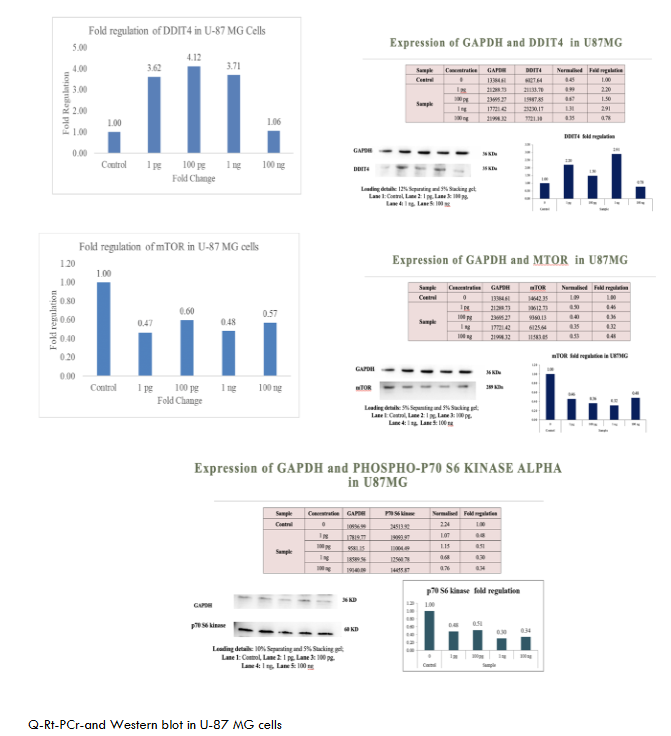

The proteins were transferred to methanol-activated PVDF membranes Invitrogen via a Turbo transblot system (Bio-Rad, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% BSA for 1 hr and incubated with the appropriate primary antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with a species-specific secondary antibody for 1 hr at RT. The blots were washed and incubated with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (Merck) for 1 min in the dark, and images were captured at appropriate exposure settings via a ChemiDoc XRS system (Bio-Rad, USA). The Figures 1-6 show metadichol exerts profound effects on the DDIT4-mTOR-p70S6K signaling axis at concentrations several orders of magnitude lower than conventional mTOR modulators. In peripheral blood mononuclear cells PBMCs, treatment with metadichol at concentrations ranging from 1 pg/mL to 100 ng/mL resulted in dose-dependent upregulation of DDIT4 expression, with maximum effects observed at 1 pg/mL (10⁻¹² g/mL). At this concentration, DDIT4 mRNA levels increased significantly compared to vehicle-treated controls (p < 0.001), while protein levels showed corresponding increases as determined by Western blot analysis. Concomitant with DDIT4 upregulation, metadichol treatment resulted in significant downregulation of both mTOR and p70S6K expression and activity. mTOR mRNA levels decreased significantly (p < 0.001), while phosphorylation of mTOR at Ser2448, a key indicator of mTOR activity, was substantially reduced (p < 0.001). Similarly, p70S6K mRNA expression decreased significantly (p < 0.001), and phosphorylation at Thr389, the critical activation site, was markedly reduced (p < 0.001).

The exceptional potency of metadichol becomes apparent when compared to conventional mTOR inhibitors. (See Table 1) Rapamycin, the prototypical mTOR inhibitor, typically requires concentrations in the nanomolar range 1-100 nM, approximately 0.91-91 ng/mL to achieve comparable effects on mTOR signaling. Everolimus, a rapamycin analog, demonstrates activity at 1-20 nM approximately 1-20 ng/mL. In contrast, metadichol achieves superior effects at 1 pg/mL, representing a concentration that is 1,000 to 100,000-fold lower than these established inhibitors.

Consistent Effects Across Multiple Cancer Cell Lines

To evaluate the broad-spectrum activity of metadichol, we assessed its effects across a panel of cancer cell lines representing different tissue origins and molecular characteristics. As shown in Figures 1-6. These consistent effects across diverse cancer cell lines demonstrate the universal nature of metadichol’s activity and suggest that its mechanisms of action are fundamental to cellular regulation rather than being dependent on specific genetic backgrounds or tissue origins.

Discussion

Metadichol, a nanoemulsion of long-chain alcohols, has emerged as a multifaceted modulator of cellular signaling, with documented effects on many pathways and its downstream effector, P70S6K. Our findings (table 7) shows that metadichol upregulates DDIT4 at a concentration of 1 pg/ml, leading to the suppression of mTORC1 activity and subsequent inhibition of P70S6K expression. This finding aligns with the established role of DDIT4 as a stress-induced inhibitor of mTORC1, which is mediated through the TSC1/TSC2 complex.

| Cell Line | DDIT4 Expression | mTOR Expression | p70S6K Expression | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC | Upregulated | Downregulated (1 pg/mL) | Downregulated (100 ng/mL) | Immune-modulatory potential; delayed p70S6K response suggests dose dependency. |

| U87MG | Upregulated | Downregulated | Downregulated | Strong anti-proliferative effects for glioblastoma. |

| Hep G2 | Upregulated | Downregulated | No significant change | Possible resistance to p70S6K inhibition; alternative pathways active. |

| MDA-MB-231 | Upregulated | Downregulated | Downregulated | Robust anticancer potential for breast cancer. |

| A549 | Upregulated | Downregulated | Downregulated (100 ng/mL) | Dose-dependent p70S6K inhibition; effective in lung cancer. |

| HCT-116 | Upregulated | Downregulated | Downregulated (0.44-fold at 100 ng/mL) | Dose-dependent effects; significant p70S6K suppression in colon cancer. |

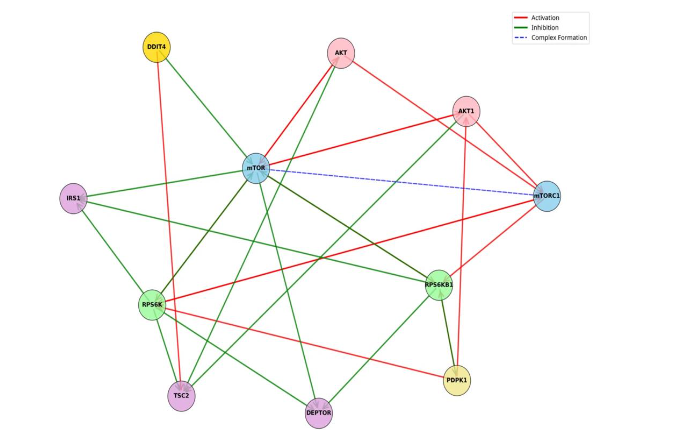

In addition, using SIGNOR, a repository of manually annotated causal relationships between proteins, (table 8) shows the detailed interactions of the proteins involved in the mTOR network and these interactions visually expressed (Figure 7) showing the network transcriptional factors that play a role in mTOR inhibition.

| Source Name | Source Category | Target Name | Target Category | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKT | Protein | mTORC1 complex | activation | |

| AKT | Protein | TSC2 | protein | inhibition |

| AKT | Protein | MTOR | protein | activation |

| AKT1 | protein | mTORC1 complex | activation | |

| AKT1 | protein | TSC2 | protein | inhibition |

| AKT1 | protein | mTOR | activation | |

| DDIT4 | protein | TSC2 | protein | activation |

| MTOR | protein | RPS6KB1 | protein | activation |

| MTOR | protein | AKT | protein | activation |

| MTOR | protein | AKT1 | protein | activation |

| MTOR | protein | RPS6K | protein | activation |

| MTOR | protein | mTORC1 complex | complex-formation | |

| MTOR | protein | IRS1 | protein | inhibition |

Broader implications and signaling pathway

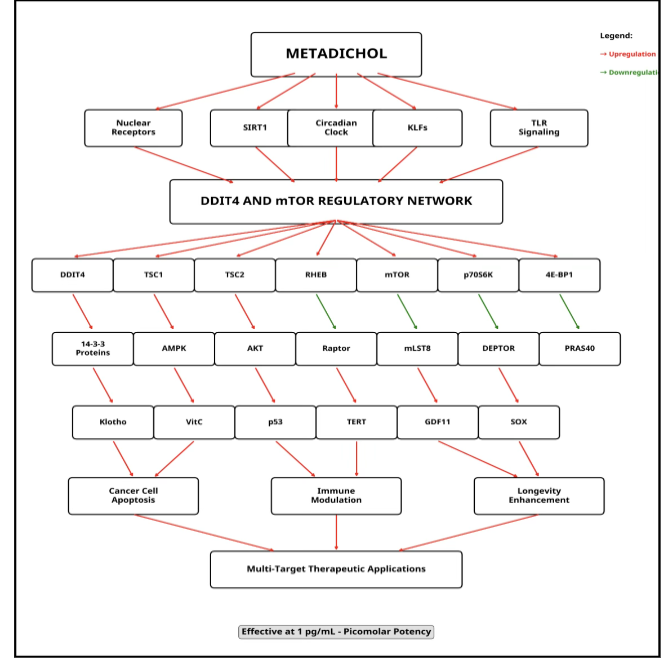

Kruppel-like factors KLFs, such as KLF2 and KLF4, as transcriptional regulators of DDIT4 in response to Metadichol. However, the broad bioactivity of metadichol suggests that additional mechanisms may contribute to mTOR and P70S6K suppression, potentially via nuclear receptor-mediated expression of sirtuins and Toll-like receptor TLR signaling pathways. Nuclear receptors (NRs), including PPARs, LXR, and VDR, are ligand-activated transcription factors that regulate metabolic and stress response genes. Given the structural similarity of metadichol to lipid-derived molecules, it may serve as a ligand or coactivator for these receptors. Notably, PPARγ and VDR have been linked to the transcriptional upregulation of SIRT1, an NAD+-dependent deacetylase with established roles in metabolic regulation. Metadichol can increase SIRT1 expression, suggesting that this effect is NR dependent.

NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) is a plausible mediator of mTOR suppression. It activates AMPK through the deacetylation of LKB1, an upstream kinase that phosphorylates TSC2, thereby inhibiting mTORC1. This SIRT1-AMPK-mTOR axis represents a metabolic regulatory pathway distinct from the stress-induced KLF/DDIT4 mechanism. In the context of metadichol, NR-mediated SIRT1 upregulation could amplify AMPK activity, reducing mTORC1 signaling and P70S6K phosphorylation independently of DDIT4. Additionally, the promotion of autophagy by SIRT1, which is inhibited by active mTORC1, may further suppress P70S6K activity, as P70S6K negatively regulates autophagic flux.

Toll like receptor (TLR) Signaling as an Alternative Regulatory Pathway Metadichol’s ability to modulate TLRs offers another potential avenue for mTOR and P70S6K suppression. TLRs, which are critical to innate immunity, also influence metabolic pathways through crosstalk with mTORC1. Typically, TLR activation e.g., via LPS stimulates mTORC1 via PI3K/Akt signaling, promoting inflammation and cell survival. However, metadichol has a unique profile, modulating the expression of TLR1–10 and downregulating downstream adaptors such as MYD88, TRAF6, and IRAK4 in cancer cell lines. This suppression of TLR signaling components could disrupt Akt-driven mTORC1 activation, leading to reduced P70S6K activity.

Moreover, SIRT1 may intersect with TLR signaling by deacetylating NF-κB, attenuating inflammatory responses that otherwise sustain mTOR activity. Metadichol simultaneously upregulates SIRT1 via NRs and dampens TLR signaling; this dual action could synergistically inhibit mTORC1. Unlike the KLF/DDIT4 pathway, which relies on transcriptional stress responses, TLR-mediated effects involve immune–metabolic crosstalk, offering a distinct mechanism.

In addition to SIRT1 and TLRs, nuclear receptors such as PPARα might directly regulate autophagy-related genes e.g., ULK1 that intersect with mTOR signaling, suggesting additional layers of control. The low concentration 1 pg/ml at which Metadichol upregulates DDIT4 highlights its potency via the KLF pathway, but alternative mechanisms involving SIRT1 or TLRs may operate at different thresholds or in different cellular contexts, reflecting the pleiotropic nature of Metadichol. This complexity underscores its potential as a therapeutic agent.

Circadian Genes

Metadichol also expresses circadian genes. A considerable body of evidence has demonstrated robust interplay between the mTOR pathway and the circadian clock. This interaction is not unidirectional; it is a dynamic interplay where each system influences the other. The mTOR pathway can influence the period length and synchronization of the circadian clock, affecting the timing and amplitude of circadian oscillations. Conversely, the circadian clock can regulate mTOR activity through the rhythmic expression of mTOR regulators or through the temporal control of nutrient availability. For example, the rhythmic expression of genes involved in nutrient sensing and metabolism can impact mTOR signaling. This bidirectional relationship underscores the importance of their coordinated function in maintaining cellular homeostasis and adaptation to environmental changes. Disruptions in this delicate balance can have profound consequences for cellular health and contribute to disease development.

The effects of metadichol on DDIT4, mTOR, and p70S6K involve coordinated regulation by SIRT1, VDR, PPAR, Klotho, telomerase, vitamin C, KLF, Foxo1, and circadian genes. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) inhibits mTOR and p70S6K via AMPK and Akt, potentially inducing DDIT4. NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) enhances NAD+ availability, suppressing mTOR and p70S6K while modulating DDIT4. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α) suppresses mTOR and promotes DDIT4 via metabolic adaptation. Circadian genes link rhythmicity to mTOR suppression, with SIRT1 as an integrator. In PBMCs and cancer cell lines, metadichol may upregulate SIRT1 and VDR, activating PPAR and circadian pathways to inhibit mTOR/p70S6K-driven proliferation while inducing DDIT4. These findings support its anticancer and immunomodulatory potential. The broad actions on many pathways by Metadichol actions are summarized in Figure 8.

Metadichol downregulates both mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) and p70S6 kinase (p70S6K) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and cancer cell lines. This regulation of key cancer pathways carries several major implications.

- Reduced Cell Proliferation and Growth: mTOR and p70S6K are key regulators of protein synthesis, cell growth, and proliferation. Their downregulation could inhibit cancer cell growth and division.

- Increased Autophagy: mTOR inhibition promotes autophagy, which can act as a tumor suppressor mechanism by eliminating damaged cellular components.

- Decreased Cancer Stem Cell Activity: mTOR signaling is crucial for cancer stem cell maintenance and self-renewal. Its inhibition may restore enhanced therapeutic sensitivity.

- Overcoming Drug Resistance: Constitutive activation of p70S6K is associated with cisplatin resistance in some cancers. Downregulation of this pathway could potentially resensitize resistant tumors to chemotherapy.

- Synergy with Other Therapies: Inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K signaling may enhance the efficacy of other cancer treatments, including targeted therapies and immunotherapies.

- Altered Cellular Metabolism: mTOR is a central regulator of cellular metabolism. Its inhibition could disrupt cancer cells’ metabolic adaptations, potentially making them more vulnerable to stress.

- Immune System Modulation: In PBMCs, mTOR inhibition can promote the development of memory cells and enhance overall immune response.

Potential Therapeutic Applications

Metadichol might be particularly effective against cancers with PTEN mutations or deletions, where mTOR signaling is often hyperactivated.

Conclusions

Our study, a systems-level approach to transcriptional modulation demonstrated by Metadichol, represents a paradigm shift from single-target therapeutics toward comprehensive network-based interventions. This multi-target strategy may prove particularly valuable for complex age-related diseases that involve dysfunction across multiple physiological systems.

The remarkable safety profile of Metadichol is established, and its ability to enhance rather than replace normal cellular functions makes it an attractive candidate for regenerative medicine applications where long-term treatment may be required. Clinical use of Metadichol supports rapid translation of these findings toward therapeutic applications.

Metadichol likely suppresses mTOR and P70S6K through multiple pathways in addition to KLF-mediated DDIT4 upregulation. Nuclear receptor-driven SIRT1 expression and TLR signaling modulation represent additional avenues for leveraging the metabolic AMPK and immune–metabolic Akt axes, respectively. Additionally, it affects circadian genes that regulate mTOR signaling. These mechanisms, which are potentially synergistic, highlight the versatility of metadichol while distinguishing it from conventional mTOR inhibitors. Future studies should prioritize the dissection of these pathways to clarify their contributions and therapeutic relevance.

The novelty of our findings, combined with their clinical relevance and translation potential, positions this work as a foundation for future therapeutic development in immune enhancement and regenerative medicine. This work establishes metadichol as a unique molecular tool for studying transcriptional network regulation and provides a foundation for developing novel therapeutic approaches based on coordinated transcriptional reprogramming.

Supplementary Statements.

This paper was published and is available at. Preprints 2025 and is available at https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202504.1573.v1

The author is the founder and CEO of Nanorx Inc., NY, USA, in which he is a majority shareholder.

Raw-data file: q-RT-PCR-raw data.

PDF File; mTOR-Interaction network

References

- Panwar V, Singh A, Bhatt M, et al. Multifaceted role of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway in human health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):375. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01608-z

- Liu GY, Sabatini DM. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(4):183-203. doi:10.1038/s41580-019-0199-y

- Xie J, Wang X, Proud CG. mTOR inhibitors in cancer therapy. F1000Res. 2016;5:2078. doi:10.12688/f1000research.9207.1

- Klawitter J, Nashan B, Christians U. Everolimus and sirolimus in transplantation-related but different. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(7):1055-1070. doi:10.1517/14740338.2015.1046832

- Kim JY, Kwon YG, Kim YM. The stress-responsive protein REDD1 and its pathophysiological functions. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55(9):1933-1944. doi:10.1038/s12276-023-01056-3

- Brugarolas J, Lei K, Hurley RL, et al. Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev. 2004;18(23):2893-2904. doi:10.1101/gad.1256804

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 20):3589-3594. doi:10.1242/jcs.051011

- Rohde J, Heitman J, Cardenas ME. The TOR kinases link nutrient sensing to cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(13):9583-9586. doi:10.1074/jbc.R000034200

- Castro AF, Rebhun JF, Clark GJ, Quilliam LA. Rheb binds tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) and promotes S6 kinase activation in a rapamycin- and farnesylation-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(35):32493-32496. doi:10.1074/jbc.C300226200

- Zhou H, Huang S. The complexes of mammalian target of rapamycin. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2010;11(6):409-424. doi:10.2174/138920310791824093

- Kim YC, Guan KL. mTOR: a pharmacologic target for autophagy regulation. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(1):25-32. doi:10.1172/JCI73939

- Yong J, Kim H, Lee E, Jung Y. Regulation of transcriptome plasticity by mTOR signaling pathway. Exp Mol Med. 2025;57(1):1-15. doi:10.1038/s12276-025-01508-y

- Vézina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal SN. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1975;28(10):721-726. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.28.721

- Sehgal SN, Baker H, Vézina C. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. II. Fermentation, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1975;28(10):727-732. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.28.727

- Kahan BD, Gibbons S, Tejpal N, Stepkowski SM, Chou TC. Synergistic interactions of cyclosporine and rapamycin to inhibit immune performances of normal human peripheral blood lymphocytes in vitro. Transplantation. 1991;51(1):232-239. doi:10.1097/00007890-199101000-00041

- Dumont FJ, Staruch MJ, Koprak SL, Melino MR, Sigal NH. Distinct mechanisms of suppression of murine T cell activation by the related macrolides FK-506 and rapamycin. J Immunol. 1990;144(1):251-258.

- Brown EJ, Albers MW, Shin TB, et al. A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin-receptor complex. Nature. 1994;369(6483):756-758. doi:10.1038/369756a0

- Sabatini DM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Lui M, Tempst P, Snyder SH. RAFT1: a mammalian protein that binds to FKBP12 in a rapamycin-dependent fashion and is homologous to yeast TORs. Cell. 1994;78(1):35-43. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90570-3

- Keith CT, Schreiber SL. PIK-related kinases: DNA repair, recombination, and cell cycle checkpoints. Science. 1995;270(5233):50-51. doi:10.1126/science.270.5233.50

- Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN. Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science. 1991;253(5022):905-909. doi:10.1126/science.1715094

- Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, et al. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell. 2002;10(3):457-468. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00636-6

- Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, et al. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2004;14(14):1296-1302. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054

- Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, et al. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110(2):163-175. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5

- Hara K, Maruki Y, Long X, et al. Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell. 2002;110(2):177-189. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00833-4

- Thoreen CC, Kang SA, Chang JW, et al. An ATP-competitive mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor reveals rapamycin-resistant functions of mTORC1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(12):8023-8032. doi:10.1074/jbc.M900301200

- Wang L, Harris TE, Roth RA, Lawrence JC Jr. PRAS40 regulates mTORC1 kinase activity by functioning as a direct inhibitor of substrate binding. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(27):20036-20044. doi:10.1074/jbc.M702376200

- Jung CH, Ro SH, Cao J, Otto NM, Kim DH. mTOR regulation of autophagy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(7):1287-1295. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.017

- Hosokawa N, Hara T, Kaizuka T, et al. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(7):1981-1991. doi:10.1091/mbc.e08-12-1248

- Jacinto E, Loewith R, Schmidt A, et al. Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(11):1122-1128. doi:10.1038/ncb1183

- Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307(5712):1098-1101. doi:10.1126/science.1106148

- Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, et al. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22(2):159-168. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029

- Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129(7):1261-1274. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009

- Guertin DA, Stevens DM, Thoreen CC, et al. Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor or rictor reveals differential sensitivity to rapamycin. Mol Cell. 2006;21(4):543-551. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.028

<li