Cognitive Style and Coping Strategies in Stress Management

An Empirical Study of the Interrelations Between Cognitive Style, Coping Strategies, and the Creative Component of Personality in the Context of Stress Management

Kokorina Yuliia1, PhD Sementsova Мariia 2

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 September 2025

CITATION: YULIIA, Kokorina; МARIIA, Sementsova. An Empirical Study of the Interrelations Between Cognitive Style, Coping Strategies, and the Creative Component of Personality in the Context of Stress Management. Medical Research Archives, Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6840>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6840

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Background: This article examines the interrelationships among cognitive style, coping behavior, and the creative dimension of personality within the framework of stress management.

Aims: This study focuses on the role of cognitive style, coping strategies, and the creative dimension of personality in overcoming stress.

Methods: This study involved a sample of 44 participants. The basic psychodiagnostic methods used were: the Personal Differential Method (A. & B. Pease) assesses whether an individual demonstrates an analytical-logical or emotional-intuitive type of thinking; the Questionnaire for Determining General Emotional Orientation (B. Dodonov) is used to assess the creative component of personality; the “Coping Strategies” Questionnaire by R. Lazarus allows for the assessment of the main forms of coping behavior that a person typically uses in stressful situations; the Gottschaldt Figures Test assesses the cognitive style parameter of field dependence/independence. Statistical analyses of empirical data and graphical presentation of results were conducted using the SPSS v.21.0 statistical software package. To verify the statistical significance of differences in cognitive style and the creative component in the context of stress management, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis H test were applied.

Results: The influence of the cognitive style “field dependence/field independence” and creative components—specifically, “type of thinking” and “emotional orientation”—on respondents’ coping strategies for overcoming stress was analyzed. Through comparative analysis, it was found that 50% of male respondents demonstrated a creative type of thinking, while among female respondents, the distribution was as follows: 47.5% exhibited a creative thinking style, and 37.5% showed a mixed type of thinking. The influence of cognitive style and the creative component of personality on stress coping was analyzed. The results revealed that the creative component has a significant impact on the forms of coping behavior. In particular, emotional orientation significantly influenced the choice of coping strategies, whereas no significant correlation was found between coping behavior and an individual’s type of thinking. Analysis of field-dependent/field-independent cognitive styles revealed that the majority of respondents, both male and female, exhibit a field-dependent cognitive style. It was also found that respondents who are neither employed nor enrolled in education, particularly those aged 21–30 and over 46, predominantly display a field-dependent style. The study of coping behavior among men revealed that the confrontational coping strategy is used by them exclusively as an adaptive mechanism. In contrast, for women, the levels of this strategy fall within the moderate to high range. A similar distribution was observed with respect to the location variable: respondents currently residing in Ukraine tended to employ more aggressive coping strategies.

Conclusion: The study demonstrated that the creative component of personality – specifically, emotional orientation – significantly influences the choice of coping strategies in stressful situations. Individuals with a stronger emotional orientation are more likely to use emotion-focused coping. In contrast, no significant link was found between type of thinking and coping behavior. A field-dependent cognitive style was more common among both male and female respondents, particularly among those not engaged in work or study. Gender and location differences were also identified: men tended to use confrontational strategies adaptively, while respondents living in Ukraine showed a greater tendency toward aggressive coping behavior. These results emphasize the role of individual psychological traits in shaping coping mechanisms.

Keywords

coping strategy, creative component, cognitive style, type of thinking, emotional orientation, field dependence/field independence, stress.

Introduction

Ukraine is currently in a state of war, exerting a large-scale and multifaceted impact on the population’s mental and physical health. Contemporary studies report a significant increase in moderate to severe anxiety, a high prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among refugees and internally displaced persons (93% of cases)1, a rise in depressive and anxiety disorders2,3,4, and changes in the subjective perception of time5,6.

Under these circumstances, examining the interrelationships between cognitive style, coping strategies, and the creative component of personality in the process of stress management becomes particularly relevant. Cognitive style shapes the perception and interpretation of events, influencing the appraisal of stressful situations and the selection of coping strategies7,8. The creative component of personality expands the range of possible interpretations and solutions, enhances response flexibility, and facilitates the use of both conventional and innovative coping strategies9,10.

Previous research has shown that the foundations of psychological resilience in the context of war, migration, and prolonged stress may include meaning-making and value reorientation11,12,13, positive emotions14, embodied and emotionally rich experiences15,16, as well as flexibility and openness to new experiences17,18,19. However, it is the interaction between cognitive characteristics and creative traits that may determine which coping strategies are chosen and how effective they are.

Evidence from different samples—adolescents20,21, university students5, rescue workers22, and military personnel23,24,25 – confirms that personality dispositions and cognitive appraisal of situations are directly related to coping behavior. In open and constantly changing life circumstances, the ability to creatively interpret events creates opportunities for finding new solutions, even in the most challenging conditions.

Thus, the effectiveness of stress coping is determined not only by each of the three factors independently, but also by their mutual influence. Purposeful development of cognitive flexibility, creative potential, and adaptive coping strategies may form the basis for psychological interventions aimed at strengthening individual resilience in wartime conditions. The aim of this study is to examine the role of cognitive style, coping strategies, and the creative component of personality in the process of coping with stress, particularly in the context of military conflict.

The authors hypothesize that an individual’s cognitive style – specifically, field dependence vs. field independence – significantly influences the selection of coping strategies in stressful situations.

Methods

Participants

The empirical study was conducted using the Google Forms online platform in the format of a cross-sectional survey. Eligibility criteria required that participants be 18 years of age or older. The three-month survey, in addition to the selected diagnostic methods used to examine the specified relationship, incorporated socio-demographic questions on age, gender, occupation, and place of residence. All participants provided online informed consent before completing the questionnaire. They were informed that the questionnaire was entirely anonymous and that they would receive feedback regarding their results.

The study involved 44 respondents – 40 women and 4 men, aged 18 to 77, all of whom were Ukrainian citizens, either currently residing in Ukraine or having been forcibly displaced abroad. The largest age group was 31–45 years (43.1%), followed by respondents aged 21–30 (20.5%), under 20 (18.2%), 46–60 (11.4%), and over 60 (6.8%). The majority of participants (77.3%) were living in Ukraine at the time of the survey, while 22.7% had been forced to leave the country.

Data-Collection

Throughout the study, a set of diagnostic instruments was employed to achieve the stated research objectives: The Personal Differential Method (A. & B. Pease) was used to determine whether an individual demonstrates an analytical-logical or emotional-intuitive thinking style; The Questionnaire for Determining General Emotional Orientation26 (B. Dodonov) was applied to assess the creative component of personality; The Coping Strategies Questionnaire developed by R. Lazarus7 was used to examine the primary forms of coping behavior typically employed by individuals in stressful situations; The Gottschaldt Figures Test27,28 was utilized to measure a key parameter of cognitive style – specifically, field dependence versus field independence.

Statistical processing of the empirical data and graphical presentation of the results were carried out using the SPSS v.21.0 statistical software package. To assess the statistical significance of differences in cognitive style and the creative component of personality in coping with stress, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis H test were applied.

Results

Qualitative and Comparative Analysis of Thinking Style and Emotional Orientation of Personality

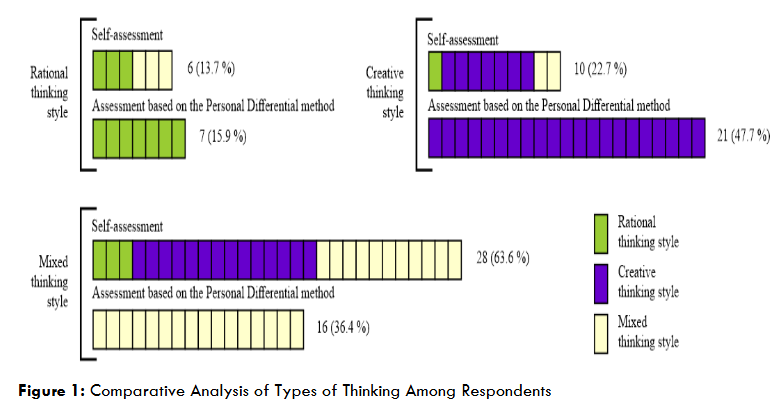

In the course of the study, respondents were asked to subjectively evaluate their own thinking style as rational, creative, or mixed, followed by an objective assessment using the Personal Differential Method.

While the majority of respondents (63.6%) self-identified their thinking style as mixed, the results of the Personal Differential Method indicated that most of them (47.7%) were in fact classified as having a creative thinking style. Notably, the subjective and test-based assessments of thinking style matched in 50% of respondents with a rational thinking style, 70% with a creative thinking style, and 39% with a mixed thinking style. These findings are graphically illustrated in the figure 1.

Subjective and test-based assessments of thinking style coincided in 50% of male respondents and 90% of female respondents (see Table 1).

| Gender | Type of thinking | Subjective Self-Assessment | Personal Differential Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Rational | 1 (25%) | 1 (25%) |

| Creative | 0 (0%) | 2 (50%) | |

| Mixed | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | |

| Female | Rational | 5 (12.5%) | 6 (15%) |

| Creative | 10 (25%) | 19 (47.5%) | |

| Mixed | 25 (62.5%) | 15 (37.5%) |

It is noteworthy that none of the male respondents subjectively identified their thinking style as creative. However, based on the Personal Differential Method, 50% of participants in this group were objectively classified as having a creative thinking style. It should be emphasized that, due to the limited number of male participants, further research is necessary to either confirm or challenge these findings.

An analysis of psychological theories of creativity and the creative personality suggests that emotional orientation is a system-forming factor in the manifestation of creativity. Accordingly, the general emotional orientation was assessed using B. Dodonov’s methodology.

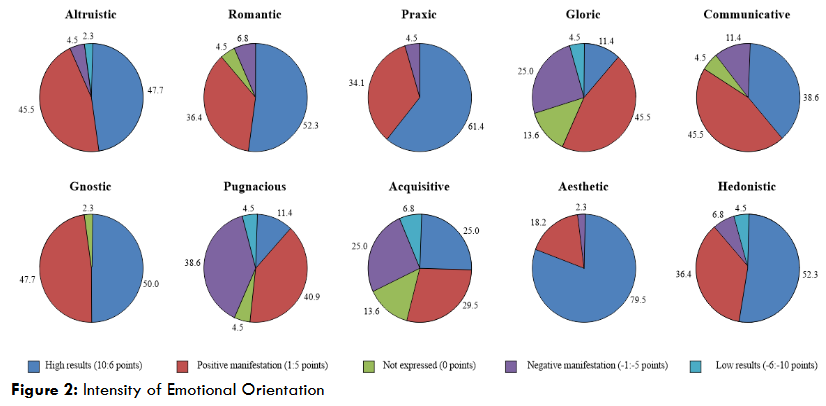

It was found that 79.5% of respondents exhibited a pronounced need for the perception of beauty. This group tends to experience strong resourceful emotions in response to aesthetic stimuli. Additionally, 61.4% of respondents demonstrated a need for active engagement and a desire to achieve results.

None of the respondents demonstrated a high need for solitude, passivity toward activity, or indifference to aesthetic experiences. Thus, the majority of respondents exhibited emotional interest in exploring new experiences. This characteristic was absent in only 2.3% of the sample. The participants also showed a low tendency toward pragmatism. The distribution of respondents according to the intensity of their needs is presented in the figure.

Thus, the “aesthetic emotional orientation” received the highest score in 21.4% of respondents. Notably, no low scores were recorded in this category within the sample. In the low negative range, the following emotional orientations were identified: “pugnacious” (12.2%) and “acquisitive” (10.2%). Respondents exhibiting these tendencies showed a greater inclination toward risk over caution, as well as a marked tendency toward avoidance. These patterns may represent a typical psychological response to loss, uncertainty, and threat among respondents who have experienced a profound life disruption – the war in their country – and were forced to leave their homes and material possessions.

Specifically, the “pugnacious” emotional orientation may reflect a dominant influence of anxious anticipation, feelings of helplessness, and a diminished sense of subjective control. At the same time, the “acquisitive” orientation, which is normally associated with the desire to acquire and preserve, takes on a distorted meaning under conditions of forced migration – manifesting as a drive to restore what was lost, to compensate for deprivation, or to prevent further loss.

Taken together, these traits may underlie emotionally unstable and avoidant behavior, as well as a tendency to make decisions aimed at minimizing risks in the absence of a stable outlook.

To examine the relationship between thinking style and preferred emotional needs, data were obtained and are presented in the table.

| Emotional Orientation Scale | Mean rank | Kruskal–Wallis H | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n1 = 6 | n2 = 10 | n3 = 28 | |

| Communicative | 22.17 | 33.55 | 10.028 |

| Aesthetic | 17.00 | 31.10 | 6.372 |

| Acquisitive | 26.58 | 30.25 | 6.544 |

Note: n₁ = Rational thinking style, n₂ = Creative, n₃ = Mixed.

A Kruskal-Wallis test revealed statistically significant differences in emotional orientation across participants with different self-perceived cognitive styles: rational (n = 6), creative (n = 10), and mixed (n = 28).

For “communicative orientation”, H=10.028, p=.007, the creative style group (Mrank = 33.55) scored higher than the rational (Mrank = 22.17) and mixed style groups (Mrank = 18.63).

For “aesthetic orientation”, H=6.372, p=.041, the creative style group (Mrank = 31.10) scored higher than the mixed (Mrank = 20.61) and rational groups (Mrank = 17.00).

For “acquisitive orientation”, H=6.544, p=.038, both the creative (Mrank = 30.25) and rational (Mrank = 26.58) groups scored higher than the mixed style group (Mrank = 18.86).

A significant association was found between individuals’ self-reported thinking style and the following emotional orientations: “Communicative” (H = 10.028, p = 0.007), “Aesthetic” (H = 6.372, p = 0.041), and “Acquisitive” (H = 6.544, p = 0.038).

A significant association was also found between thinking style and the emotional orientations “Pugnacious” (H = 7.413, p = 0.025) and “Aesthetic” (H = 10.467, p = 0.005).

| Emotional Orientation Scale | Mean rank | Kruskal–Wallis H | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n1 = 7 | n2 = 21 | n3 = 16 | |

| Pugnacious | 15.64 | 27.90 | 7.413 |

| Aesthetic | 31.43 | 25.38 | 10.467 |

Note: n₁ = Rational thinking style, n₂ = Creative, n₃ = Mixed.

Let us consider the statistically significant associations between emotional orientation and the social variables “gender,” “age,” and “parenthood.”

It should be noted that no significant relationships were found with the variables “marital status,” “respondent’s location”, or “engagement in study or work” during the course of the research.

| Emotional Orientation Scale | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | Scale – Mann–Whitney U | p | z | r | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gloric | 6.75 | 27.00 | 24.08 | 963.00 | 17.000 | 0.010 | -2.592 |

| Pugnacious | 10.50 | 42.00 | 23.70 | 948.00 | 32.000 | 0.049 | -1.970 |

| Gnostic | 39.38 | 157.50 | 20.81 | 832.50 | 12.500 | 0.005 | -2.787 |

A Mann-Whitney U test revealed statistically significant differences between men and women on all three emotional orientation scales. For “gloric orientation” (focus on glory and recognition), women (Mrank = 24.08) scored significantly higher than men (Mrank = 6.75), U=17.00, p=.010, r= −.39, indicating a medium effect size. For “pugnic orientation” (focus on avoiding danger and exercising caution), women (Mrank = 23.70) also scored higher than men (Mrank = 10.50), U=32.00, p=.049, r= −.30, with a small effect size. In contrast, for “gnostic orientation” (focus on knowledge and the search for truth), men (Mrank = 39.38) scored higher than women (Mrank = 20.81), U=12.50, p=.005, r= −.42, reflecting a medium effect size.

| Scale | Mean Rank | Kruskal–Wallis H | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n1 = 8 | ≤ 20 | n2 = 9 | 21-30 | n3 = 19 | 31-45 | n4 = 5 | 46-60 | n5 = 3 | 61 + |

| Communicative | 37.25 | 15.61 | 19.42 | 22.10 | 24.00 | 14.383 | 0.006 |

A significant association was also found between respondents’ age and the Communicative emotional orientation (H = 14.383, p = 0.006).

| Scale | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | Scale – Mann–Whitney U | p | z | r | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Praxic | 27.89 | 18.40 | 135.00 | 0.014 | -2.445 | 0.369 | Mean rank |

A significant association was found between respondents’ parenthood status and the Praxic emotional orientation (U = 135.000, p = 0.014). Based on this finding, it can be assumed that respondents with children demonstrate a strong desire to act, to achieve set goals, and to obtain desired results — that is, parenthood may serve as a motivating factor for goal-directed activity.

Qualitative and Comparative Analysis of Emotional Orientation and Coping Strategies

The main coping strategies were assessed using the Coping Strategies Questionnaire developed by R. Lazarus. Subsequently, the obtained data were compared with the indicators of the individual’s emotional orientation by B. Dodonov’s scale. The results are presented in the table below.

| N=44 | C | o | n | f | r | D | o | i | n | s | t | t | ia | S | v | n | e | c | l | i | f | n | – | S | g | c | e | oe | nk | t | i | A | r | n | c | og | c | l | se | lop | E | p | i | c | s | t | i | n | i | c | ganal | g | p | Ps | relue | – | apsanppvfo | ou | r | onil | t | ss | dpi | iar | tb | noi | i | cb | v | ele | i | ert | mey | – | asp | op | l | r | va | i | i | ns | ga | l | Altruistic | -0.064 | -0.013 | -0.172 | 0.051 | 0.186 | -0.020 | -0.099 | 0.023 | 0.679 | 0.933 | 0.263 | 0.743 | 0.226 | 0.896 | 0.523 | 0.883 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicative | 0.191 | 0.019 | -0.016 | 0.577*** | 0.203 | 0.205 | -0.108 | 0.218 | 0.214 | 0.904 | 0.920 | 0.000 | 0.186 | 0.181 | 0.486 | 0.156 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gloric | 0.442** | -0.123 | 0.052 | 0.073 | -0.022 | 0.372* | 0.158 | 0.165 | 0.003 | 0.427 | 0.738 | 0.637 | 0.887 | 0.013 | 0.305 | 0.284 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Praxic | 0.151 | -0.225 | 0.203 | 0.340* | 0.037 | -0.113 | 0.399** | 0.495** | 0.329 | 0.141 | 0.186 | 0.024 | 0.811 | 0.467 | 0.007 | 0.001 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pugnacious | 0.358* | 0.014 | 0.063 | -0.059 | 0.109 | 0.259 | 0.045 | 0.123 | 0.017 | 0.927 | 0.685 | 0.702 | 0.481 | 0.090 | 0.772 | 0.427 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romantic | 0.417** | 0.015 | 0.111 | 0.160 | 0.357* | 0.490** | -0.202 | 0.128 | 0.005 | 0.923 | 0.473 | 0.300 | 0.017 | 0.001 | 0.189 | 0.409 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gnostic | 0.228 | -0.275 | 0.177 | 0.075 | -0.012 | 0.008 | 0.548** | 0.327* | 0.137 | 0.071 | 0.251 | 0.627 | 0.937 | 0.959 | 0.000 | 0.030 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aesthetic | 0.490** | 0.107 | 0.178 | 0.455** | 0.195 | 0.462** | 0.075 | 0.359* | 0.001 | 0.491 | 0.247 | 0.002 | 0.204 | 0.002 | 0.629 | 0.017 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hedonistic | 0.365* | 0.341* | 0.228 | 0.207 | 0.317* | 0.611*** | 0.072 | 0.086 | 0.015 | 0.023 | 0.136 | 0.177 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 0.643 | 0.581 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Acquisitive | 0.202 | 0.027 | 0.055 | 0.050 | 0.206 | 0.428** | -0.205 | 0.025 | 0.189 | 0.862 | 0.724 | 0.747 | 0.180 | 0.004 | 0.183 | 0.870 |

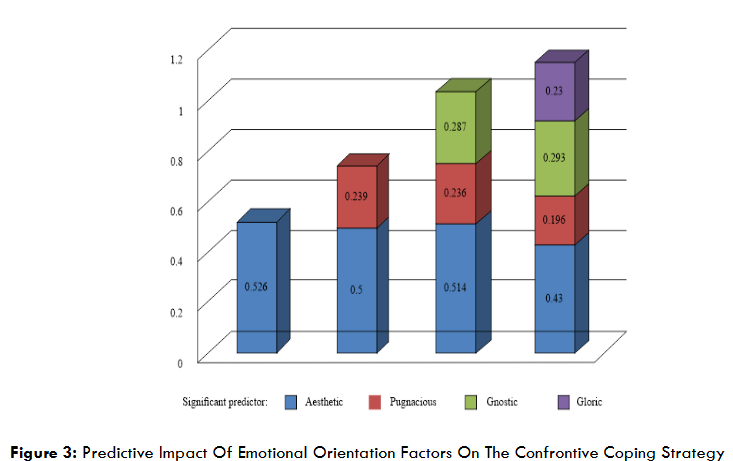

The study revealed several notable correlational patterns:

- Significant correlations were found between the creative component of Emotional Orientation and the Confrontive coping strategy. Specifically:

- Moderate positive correlations of medium statistical significance were observed with the Gloric (r = 0.442, p = 0.003), Romantic (r = 0.417, p = 0.005), and Aesthetic (r = 0.490, p = 0.001) orientations.

- Additional moderate positive correlations with lower statistical significance were found for the Pugnacious (r = 0.358, p = 0.017) and Hedonistic (r = 0.365, p = 0.015) orientations.

| Significant predictor | F | p | R | R² | cor. R² | B | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aesthetic emotional orientation | 13.282 | <0.001 | 0.490 | 0.240 | 0.222 | 0.526 | <0.001 |

| Aesthetic emotional orientation | 10.794 | <0.001 | 0.587 | 0.345 | 0.313 | 0.500 | 0.001 |

| Aesthetic emotional orientation | 9.107 | <0.001 | 0.637 | 0.345 | 0.361 | 0.514 | <0.001 |

| Aesthetic emotional orientation | 8.571 | <0.001 | 0.684 | 0.468 | 0.413 | 0.430 | 0.002 |

In the course of multiple regression analysis, the following significant predictors were introduced: Aesthetic emotional orientation (ANOVA: F = 13.282, p < 0.001); Aesthetic emotional orientation + Pugnacious emotional orientation (ANOVA: F = 10.794, p < 0.001); Aesthetic emotional orientation + Pugnacious emotional orientation + Gnostic emotional orientation (ANOVA: F = 9.107, p < 0.001); Aesthetic emotional orientation + Pugnacious emotional orientation + Gnostic emotional orientation + Gloric emotional orientation (ANOVA: F = 8.571, p < 0.001).

Although the inclusion of additional predictors increases the R² value, the explained variance remains insufficient, indicating the likelihood of other contributing factors not yet captured by the current model.

A statistically significant relationship was also observed between the creative dimensions of Emotional Orientation and the Distancing coping strategy:

- a moderate positive correlation of low statistical significance was found for the Hedonistic emotional orientation (r = 0.341, p = 0.023).

| Significant predictor | F | p | R | R² | cor. R² | B | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedonistic emotional orientation | 5.533 | 0.023 | 0.341 | 0.116 | 0.095 | 0.248 | 0.023 |

The relatively low R² value indicates the need to examine additional explanatory variables.

An increase in the Distancing coping strategy score was observed in relation to a rise in respondents’ emotional orientation:

- a one-point increase in Hedonistic orientation predicts a 0.248-point rise in the Distancing coping score.

No significant correlations or predictors were identified between creative emotional orientation and the self-controlling coping strategy.

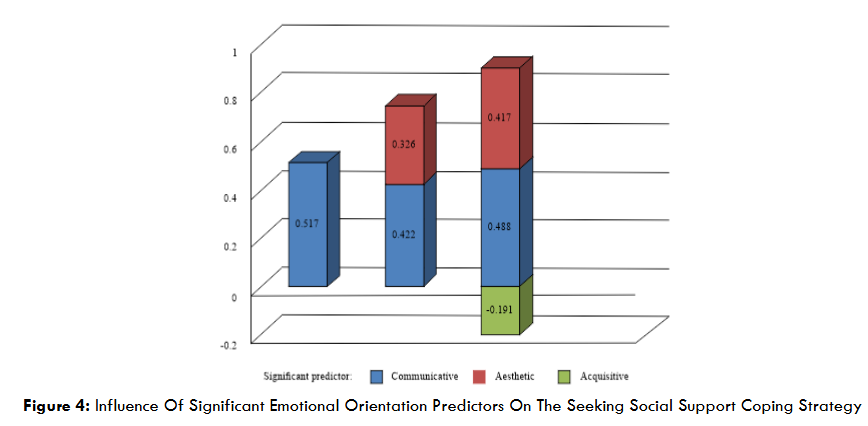

The following statistically significant associations were found between the creative component of Emotional Orientation and the Seeking Social Support coping strategy:

- a positive correlation with Communicative emotional orientation (r = 0.577, p = 0.000);

- a positive correlation with Aesthetic emotional orientation (r = 0.455, p = 0.002);

- a positive correlation with Praxic emotional orientation (r = 0.340, p = 0.024).

| Significant predictor | F | p | R | R² | cor. R² | B | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicative emotional orientation | 20.987 | <0.001 | 0.577 | 0.333 | 0.317 | 0.517 | <0.001 |

| Communicative emotional orientation | 13.340 | <0.001 | 0.628 | 0.394 | 0.365 | 0.422 | <0.001 |

| Communicative emotional orientation | 11.239 | <0.001 | 0.676 | 0.457 | 0.417 | 0.488 | <0.001 |

As more predictors were added, the R² value increased but remained relatively low, underscoring the need to identify further explanatory variables.

As shown in the figure, increases in coping strategy scores are associated with the following changes in emotional orientation levels:

- a one-point increase in Communicative orientation predicts a 0.517-point rise in the coping score;

- a one-point increase in Communicative and Aesthetic orientations predicts a 0.748-point rise;

- a one-point increase in Communicative, Aesthetic, and Acquisitive emotional orientations predicts a 0.714-point rise in the coping score.

However, a stronger need for accumulation, as reflected in Acquisitive orientation, predicts a 0.191-point decrease in the coping score.

A statistically significant relationship was identified between the creative component of Emotional Orientation and the Accepting Responsibility coping strategy:

- a moderate positive correlation with low statistical significance was found with the Romantic emotional orientation (r = 0.357, p = 0.017).

| Significant predictor | F | p | R | R² | cor. R² | B | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romantic emotional orientation | 6.131 | 0.017 | 0.357 | 0.127 | 0.107 | 0.290 | 0.017 |

The R² value remains modest, indicating the need to explore additional contributing factors.

An increase in the Accepting Responsibility coping strategy score was observed in relation to a rise in emotional orientation:

- a one-point increase in Romantic orientation predicts a 0.290-point rise in the coping score.

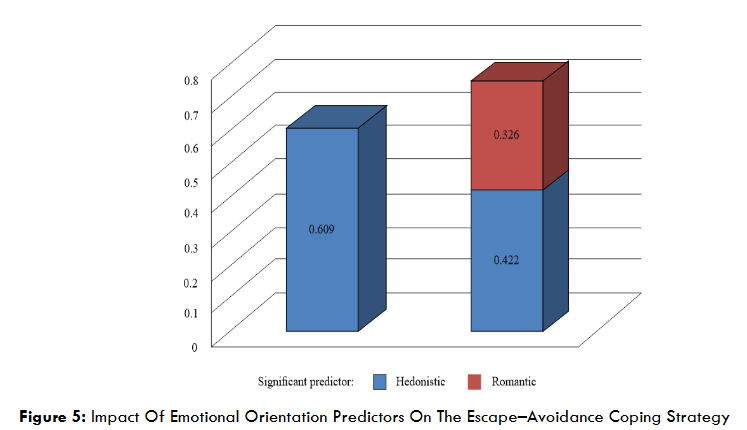

The following significant correlations were found between creative emotional orientations and the Escape–Avoidance coping strategy:

- Hedonistic (r = 0.611, p < 0.001) and Romantic (r = 0.490, p = 0.001);

- Aesthetic (r = 0.462, p = 0.002) and Acquisitive (r = 0.428, p = 0.004);

- Gloric (r = 0.372, p = 0.013).

| Significant predictor | F | p | R | R² | cor. R² | B | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedonistic emotional orientation | 25.003 | <0.001 | 0.611 | 0.373 | 0.358 | 0.609 | <0.001 |

| Hedonistic emotional orientation | 21.310 | <0.001 | 0.714 | 0.510 | 0.486 | 0.529 | <0.001 |

| Romantic emotional orientation | 0.483 | 0.002 |

As shown in the figure, increases in Escape–Avoidance scores are associated with the following changes in emotional orientation:

- a one-point increase in Hedonistic orientation predicts a 0.609-point rise in the Escape–Avoidance score;

- a one-point increase in both Hedonistic and Romantic orientations predicts a 0.748-point rise.

The creative component of emotional orientation was also significantly associated with the Planful Problem-Solving strategy:

- a strong positive correlation with high statistical significance was found with Gnostic emotional orientation (r = 0.548, p = 0.000);

- a moderate positive correlation with medium statistical significance was found with Praxic emotional orientation (r = 0.399, p = 0.007).

| Significant predictor | F | p | R | R² | cor. R² | B | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gnostic emotional orientation | 18.046 | <0.001 | 0.548 | 0.301 | 0.284 | 0.673 | <0.001 |

The R² value did not reach a satisfactory level, suggesting the need to investigate additional contributing factors.

An increase in the Planful Problem-Solving coping strategy score was observed in relation to the respondent’s emotional orientation:

- a one-point increase in Gnostic emotional orientation predicted a 0.673-point rise in the coping strategy score.

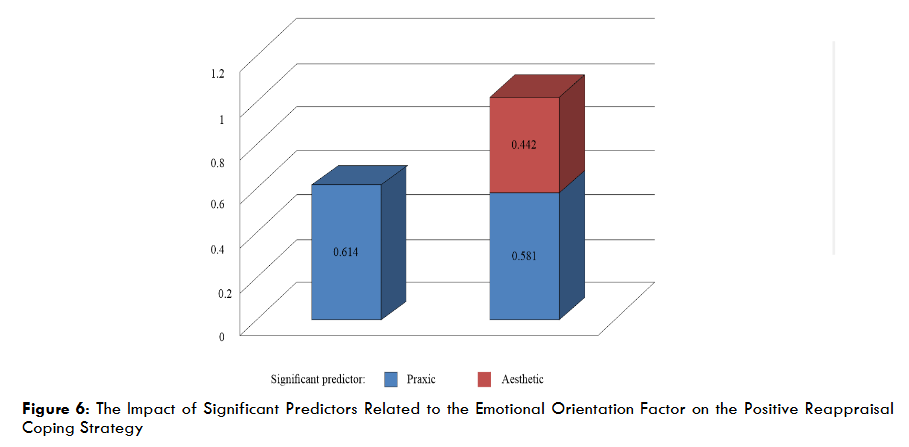

The following statistically significant associations were identified between the creative component of Emotional Orientation and the Positive Reappraisal coping strategy:

- a positive correlation with Praxic emotional orientation (r = 0.495, p = 0.001);

- a positive correlation with Gnostic emotional orientation (r = 0.327, p = 0.030);

- a positive correlation with Aesthetic emotional orientation (r = 0.359, p = 0.017).

| Significant predictor | F | p | R | R² | cor. R² | B | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Praxic emotional orientation | 13.667 | <0.001 | 0.495 | 0.246 | 0.228 | 0.614 | <0.001 |

| Praxic emotional orientation | 10.930 | <0.001 | 0.590 | 0.348 | 0.316 | 0.581 | <0.001 |

| Aesthetic emotional orientation | 0.442 | 0.015 |

As observed, the score on the Positive Reappraisal coping strategy scale increases with higher levels of emotional orientation, as follows:

- with each one-point increase in Praxic emotional orientation, the coping strategy score increases by 0.614;

- with each one-point increase in both Praxic and Aesthetic emotional orientations, the score increases by 1.023.

Thus, the creative component of Emotional Orientation plays a significant role in the selection of coping strategies, while the creative component of Thinking Style does not show a statistically significant influence on this choice. However, Thinking Style is significantly associated with Emotional Orientation.

Exploring the Relationships Between Cognitive Style and Coping Strategies in the Process of Stress Management

To explore how the creative component of personality influences the choice of coping behavior under stress, the Gottschaldt Figures Test was administered, and respondents were categorized into three groups based on their results:

- Group 1: respondents with a field-dependent cognitive style (59.9%);

- Group 2: respondents with a field-independent cognitive style (9.09%);

- Group 3: respondents who declined to complete the test (31.82%).

| field-dependent | field-independent | Group | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 4.5 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Female | 56.8 | 4.5 | 29.5 | |

| Age | Under 20 | 11.4 | 2.3 | 4.5 |

| 21-30 | 13.6 | 0.0 | 4.5 | |

| 31-45 | 22.7 | 6.8 | 13.6 | |

| 46-60 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 2.3 | |

| 60 + | 2.3 | 0.0 | 4.5 | |

| Relationships | Single | 27.3 | 6.8 | 13.6 |

| In a relationship | 31.8 | 2.3 | 18.2 | |

| Parenthood status | Has children | 27.3 | 4.5 | 11.4 |

| No children | 31.8 | 4.5 | 20.5 | |

| Employment status | Employed/Studying | 43.2 | 9.1 | 25.0 |

| Unemployed / Not in education / Receiving social assistance | 15.9 | 0.0 | 6.8 | |

| Location | Ukraine | 45.5 | 9.1 | 25.0 |

| Not in Ukraine | 13.6 | 0.0 | 6.8 |

The data presented in the table 15 indicate that the majority of respondents exhibit a field-dependent cognitive style. No instances of a field-independent cognitive style were observed among respondents who were either unemployed or not in education, as well as those aged 21–30 and over 46.

No statistically significant correlations were found between coping strategies, the creative components of thinking style and emotional orientation, and the respondents’ cognitive style (field dependence/independence).

However, a statistically significant negative correlation was found between the coping strategy “Escape-Avoidance” and the test completion time (r = –0.342, p = 0.023). It can be assumed that the less time a respondent spends completing the test, the more likely they are to use this coping strategy. However, when individual groups were systematically excluded from the analysis, this correlation disappeared once the third group – those who refused to complete the test – was omitted.

Discussion

In the present study, conducted among respondents who had experienced war and forced migration, aesthetic emotional orientation emerged as predominant, while pugnic and acquisitive orientations were less pronounced. This does not indicate their absence but rather their transformation: the pugnic orientation reflects underlying anxiety, diminished perceived control, and avoidant behavior; the acquisitive orientation reflects efforts to restore or safeguard resources after losses. This aligns with transactional model7, where aesthetic orientation can function as emotion-focused coping, sustaining a positive emotional state through values resilient to external loss.

Similarly, in Conservation of Resources theory29, it represents a non-material resource that helps preserve identity, particularly when material resources have been depleted – a finding that resonates with contemporary work on aesthetic experiences as resilience factors in trauma recovery14,16. In contrast, pugnic and acquisitive orientations in this context correspond to threat avoidance and resource protection, supporting Hobfoll’s notion of “resource defense” under chronic stress.

Differences in cognitive styles further clarify this picture. The rational style was characterized by pronounced acquisitive and aesthetic orientations, which, in the context of loss and resource scarcity, may be interpreted as a tendency to preserve and accumulate values, including through the objectification of aesthetic experience. Such patterns echo Kirton’s30 observations that more structured, analytic cognitive styles prioritize stability and resource preservation. The heightened need for safety among rational thinkers in this study reflects the activation of protective mechanisms, aligning with Allinson & Hayes31,32, who found that structured cognitive approaches often correlate with risk-averse coping.

In contrast, the creative style combined aesthetic and communicative orientations, suggesting that social interaction serves as a key coping resource. The observed risk-taking tendency may serve a dual function-mobilizing activity under uncertainty and seeking novelty to alleviate emotional tension – paralleling findings by Kirton30 and Zhang & Sternberg33,34 that innovative cognitive styles are more likely to embrace change-oriented coping. Respondents with a mixed cognitive style consistently demonstrated the lowest scores across all emotional orientations, possibly reflecting a more balanced emotional profile or motivational reorientation toward other adaptive goals.

Gender and age differences add further nuance to the results. Higher gloric and pugnic orientations in women indicate a stronger focus on social recognition and threat avoidance-strategies which, in wartime, may function to preserve safety and social resources. These findings are consistent with meta-analyses35, which show that women tend to adopt more socially-oriented and threat-avoidant coping strategies. Conversely, men’s higher gnostic orientation suggests an emphasis on cognitive control and the search for meaning through knowledge acquisition, aligning with research on gender differences in information-seeking coping36. Age-related analysis showed that communicative orientation was highest among respondents under 20 and between 46 and 60 years of age, highlighting the role of interpersonal interaction as a key adaptive resource—findings that correspond with socioemotional selectivity theory37 and work on social capital as a resilience factor38,39.

Conclusions

In a study on the role of cognitive style, coping behavior, and the creative component of personality in stress management, individuals with a field-independent cognitive style tended to base decisions on facts and personal experience, while those with a field-dependent style relied more on the overall picture and situational context. The study did not identify a significant relationship between the cognitive style of “field dependence/field independence” and coping behavior. This finding suggests that, under wartime conditions, the influence of this factor may diminish. However, it should be noted that the number of respondents with a field-independent style was small, indicating the need for further investigation.

The creative component showed a significant impact on coping behavior. Creative emotional traits facilitated flexible coping by enabling adaptive combinations of strategies according to context and personal characteristics. A significant relationship was found between the creative component of emotional orientation and coping strategy selection, but not between thinking style and coping strategies.

Problem-focused coping (PFC) and emotion-focused coping (EFC) were closely related, with the most adaptive behavior involving the integration of multiple strategies to maintain emotional regulation and stability. These findings underscore the importance of the creative dimension of personality in resilience-building and suggest avenues for targeted interventions to support psychological well-being.

References

- Lushchak O, Velykodna M, Bolman S, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among Ukrainians after the first year of Russian invasion: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2023;36:100773.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100773

- Kurapov A, Balashevych O, Borodko Y, Vovk Y, Borozenets A, Danyliuk I. Psychological wellbeing of Ukrainian civilians: a data report on the impact of traumatic events on mental health. Front Psychol. 2025;16:1553555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21933

- Osokina O, Silwal S, Bohdanova T, Hodes M, Sourander A, Skokauskas N. Impact of the Russian invasion on mental health of adolescents in Ukraine. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62(3):335-343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2022.07.845.

- Asanov AM, Asanov I, Buenstorf G. Mental health and stress level of Ukrainians seeking psychological help online. Heliyon. 2023;9:e21933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21933

- Plokhikh VV. Relationship between coping behavior and students’ perceptions of the passage of time. Insight Psychol Dimens Soc. 2023;(9):72-93. https://doi.org/10.32999/KSU2663-970X/2023-9-5

- Shipp AJ, Fried Y, Rousseau DM, Zimbardo PG. New perspectives on time perspective and temporal focus. J Organ Behav. 2020;41(3):235-243. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2435

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. Eur J Pers. 1987;1(3):141-169. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2410010304

- Prentice C, Zeidan S, Wang X. Personality, trait EI and coping with COVID-19 measures. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020;51:101789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101789

- Chebykin O, Sytnik S, Massanov A, Pavlova I. Research on the correlation between emotional-gnostic and personal characteristics with parameters of adolescents’ creativity. Insight Psychol Dimens Soc. 2024;(11):105-122. https://doi.org/10.32999/2663-970X/2024-11-6

- Aini M, Narulita E, Indrawati. Enhancing creative thinking and collaboration skills through ILC3 learning model: a case study. J Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2020;55(4). https://doi.org/10.35741/issn.0258-2724.55.4.59

- Tytarenko T. Self-recovery practices of Ukrainian civilians at the beginning of the war: subcultural differences. Insight Psychol Dimens Soc. 2024;(12):338-357. https://doi.org/10.32999/2663-970X/2024-12-4.

- Maddi SR. Creating meaning through making decisions. In: Wong PTP, Fry PS, eds. The Human Quest for Meaning: A Handbook of Psychological Research and Clinical Applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998:3-26.

- Tishchenko A, Ushakova I, Selyukova T. Features of decision making and sustainability in the organization among employees with different types of cognitive style of personality: field dependence and field independence. Habitus. 2021;24(1):131-135. https://doi.org/10.32843/2663-5208.2021.24.1.23

- Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):218-226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Carstensen LL, Mikels JA. At the intersection of emotion and cognition: aging and the positivity effect. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14:117-121.

- van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L. Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(97)81866-6

- Gabrys RL, Tabri N, Anisman H, Matheson K. Cognitive control and flexibility in the context of stress and depressive symptoms: the cognitive control and flexibility questionnaire. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2219. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02219.

- Blynova O, Popovych I, Hulias I, Radul S, Borozentseva T, Strilets-Babenko O, Minenko O. Psychological safety of the educational space in the structure of motivational orientation of female athletes: a comparative analysis. J Phys Educ Sport. 2022;22(11):2723-2732. http://dx.doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2022.11346

- Fahmi Hassan FS. Relationship between coping strategies and thinking styles among university students. ASEAN J Psychiatry. 2014;15(1):14-22. Available from: https://surl.li/myoexa

- Didkovska LI. Psychological characteristics of coping strategies in adolescence with different social and psychological status in the classroom. Probl Mod Psychol. 2014;24:191-202. Available from: http://nbuv.gov.ua/UJRN/Pspl_2014_24_19

- Voloshok O, Prus S. Behavioral manifestations of coping strategies in adolescence. Young Sci. 2021;1(89):146-151. https://doi.org/10.32839/2304-5809/2021-1-89-31

- Perilygina L, Mykhlyuk E. The dynamics of manifestation of professionally caused accentuations in employees of the State Emergency Service of Ukraine. In: Development and Modernization of Social Sciences: Experience of Poland and Prospects of Ukraine. Lublin: Baltija Publishing; 2017:305-322. https://doi.org/10.24195/2414-4665-2022