Long-Term Outcomes of Glaucoma Drainage Devices in Africa

A retrospective study of ten-year outcomes of glaucoma drainage device surgery in African patients

- Eye Foundation Hospital, 27 Isaac John GRA Ikeja, Lagos Nigeria

- Department of Ophthalmology, University of Port Harcourt, Choba Port Harcourt, Nigeria

- St Edmund’s Eye Hospital, Surulere, Lagos, Nigeria

- Wilmington VA Hospital, Wilmington, Delaware USA

- Glaucoma Associates of Texas

- Keliogg Eye Center, University of Michigan

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 September 2025

CITATION: Ogunro, A., Nathaniel, G. I., Odubela, T., et al. A retrospective study of ten-year outcomes of glaucoma drainage device surgery in African patients. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(10). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6983

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6983

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Background: Trabeculectomy, a commonly performed glaucoma filtration surgery, is often necessary to lower intraocular pressure and maintain visual function. However, individuals of African descent have been shown to experience higher rates of trabeculectomy failure. This poses a persistent challenge for Ophthalmologists in the region, especially when managing unsuccessful surgeries and complex forms of secondary glaucoma. In such difficult-to-treat cases, where standard surgical methods have failed or are anticipated to fail, glaucoma drainage devices are frequently utilized. This review aims to assess the efficacy and safety of Glaucoma drainage device (GDD) surgery in African eyes with glaucoma.

Materials and methods: A retrospective review of clinical records of 283 African patients that had Glaucoma drainage device implantation surgery done from November 2014 to November 2024 with at least 1 month follow up at Eye foundation Hospital Group. The data was retrieved from Electronic medical records (Indigo) and patients’ charts. The demographics, preoperative IOP (the highest IOP recorded before surgery and postoperative intraocular pressures at day 1, 1 month to 120 months, the number of glaucoma medications used preop and postop at the last clinic follow up visit, the preop visual acuity (snellen chart and converted to logMar) and at last clinic visit, IOP related surgeries, lasers done before and after GDD surgery and post-op complications were retrieved. All data were cross checked for accuracy, entered in proforma and were analyzed using commercially available statistical data management software Epi-info version 3.5.1, 7.2.5. Continuous variables were illustrated in the form of mean ±SD and categorical variables were shown in the form of frequency and percent.

Complete success is defined as intraocular pressure reduction of 20% or more in Preop intraocular pressure, Qualified success as intraocular pressure <21mmHg and <18mmHg with or without medication. Primary outcome measures were post op intraocular pressure, cumulative probability failure, visual acuity changes at 1 year, 3, 5, and 7 years. The secondary measures were the postop number of medications and complications.

Result: Complete success was achieved in 84.5%, 78.0%, 94.1%, 100% at 1year, 3, 5 and 7years respectively. Qualified success was achieved in 78.6%, 86.0%, 82.4% and 66.7% at 1year, 3, 5, and 7 years respectively with IOP at <21mmHg. At IOP of <18mmHg qualified success was achieved in 72.6%, 82.0%,76.5% and 66.7% at 1 year, 3, 5, and 7 years respectively. Complications occurred in 3.2%, which included macula edema, 1.8%, ptosis, exposed Glaucoma drainage device, dislocation of tube and encapsulated bleb, 1.1% each. Hypotony, choroidal effusion and branch retinal vein occlusion occurred in 0.7% of cases. Endophthalmitis occurred in 0.4% of cases.

Conclusion: A glaucoma drainage device can safely and effectively manage refractory glaucoma, even over an extended period of time in Africans.

Keywords

Glaucoma Drainage Device, Glaucoma drainage shunt, Intraocular pressure, Glaucoma Drainage tube.

Introduction

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that result in damage to the optic nerve, commonly due to elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). Globally, glaucoma poses a significant burden on public health, affecting millions of people. According to a systematic review and meta-analysis, the global prevalence of glaucoma is estimated to be around 3.54%, with approximately 64.3 million people affected by the condition. This burden is expected to increase substantially in the coming decades due to aging populations and changes in demographic trends.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness. Studies have shown that the prevalence of glaucoma in this region is higher compared to other parts of the world, with estimates ranging from 4.2% to 8.8%. However, despite its high prevalence, glaucoma often remains undiagnosed and untreated, leading to a disproportionate burden of blindness and visual impairment. The commonest form is the primary open angle glaucoma.

Treatments of Glaucoma include medications, laser therapy, and conventional surgery (Trabeculectomy). However, for patients with refractory glaucoma, Inflammatory glaucoma, Neovascular glaucoma, these methods may not suffice. Glaucoma drainage devices (GDDs) have emerged as a viable surgical alternative for controlling IOP in such cases. GDDs are now being utilized not only in the management of refractory end-stage glaucoma but also earlier in the treatment spectrum, and in some cases, they are even being considered as a primary surgical intervention. Some available GDDs are Baerveldt 350 and Aurolab Aqueous Drainage Implant (AADI) 350 (non-valved), Ahmed valve (FP7 & FP8 valved tube), Ahmed Clear path 250 & 350 (ACP) non-valved. However, this is a new method in this population and there is a paucity of data establishing its safety and efficacy hence this study. The initial clinical experience with glaucoma drainage device at Eye Foundation Hospital was documented in World Glaucoma Congress 2015 abstract book and World glaucoma 2019 abstract book.

This study aims to evaluate the long-term effectiveness and safety of glaucoma drainage devices (GDDs) in the management of glaucoma in Sub-Saharan Africa. Approval was obtained from Institutional Review Board.

Materials and methods

This study is a single-center retrospective study and was approved by the Eye Foundation Hospital Research Ethics Committee. The requirement for written informed consent was waived. The study is adherent to the Declaration of Helsinki for research in human subjects. The study is a single-center retrospective review conducted at Eye foundation hospital. It involved reviewing clinical records of all patients, who underwent GDD implantation surgery between November 2014 to November 2024 with at least 1 month follow up at Eye foundation Hospital Group. The study was limited to a single center because during the review period the procedure was performed exclusively by one surgeon (AO) with requisite expertise and experience. Few cases done by GIN during surgical training were closely supervised to ensure patient safety and technical consistency. This ensured consistency in surgical technique and minimized operator-related variability, thereby enhancing the reliability of the outcome assessment.

Subjects for the study were identified using hard copy operating theater register and Indigo, which is the electronic medical record software of the institution. Eye Foundation has established a network that strengthens the integration of eye care services across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels, ensuring seamless and continuous access to quality care for everyone since 1993. It supports the advancement of eye care in Nigeria and across Africa through research and training program for eye care practitioners, delivered via the Kunle Hassan Eye Foundation Academy (KHEFA).

Data were obtained from electronic medical records (Indigo) and patients’ charts. Variables included demographics, highest preoperative intraocular pressure (IOP), postoperative IOP at day 1, 1 month, and up to 120 months, number of glaucoma medications preoperatively and at final follow-up, pre- and postoperative visual acuity (Snellen, converted to logMAR), IOP-related surgeries and lasers before and after glaucoma drainage device (GDD) implantation, and postoperative complications were entered into excel sheets. Data were verified for accuracy, entered into a standardized proforma, and analyzed using Epi Info version 3.5.1, 7.2.5 by a statistician. Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages.

The preoperative and postoperative intraocular pressure changes were demonstrated by scatter plots. Cumulative probability of success and failure was demonstrated by the Kaplan-Meier curve. Comparison among continuous data was done using Anova, whereas categorical data were analyzed using χ2-test. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The IOP measured by Goldmann applanation tonometer, Snellen visual acuity, number of medications were retrieved preoperatively, and 1 day, 1 week, 4 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 years postoperatively. Postoperative additional surgeries were also recorded. Additional surgery for glaucoma or related complication was defined as any additional surgery necessitating intraocular intervention, a return to the operating room.

The primary outcome is termed as IOP reduction by 20% from baseline with or without the use of antiglaucoma medications. Complete and Qualified success is intraocular pressure less than 21mmHg and greater than 5 mmHg without or with anti-glaucoma medications and with additional glaucoma surgery respectively; and without loss of light perception. (Postoperative use of antiglaucoma medications was not a criterion for success or failure.) The common complications and their rates were identified to providing safety profile. The definition of hypotony was intraocular pressure of 5 mmHg or less in two consecutive visits.

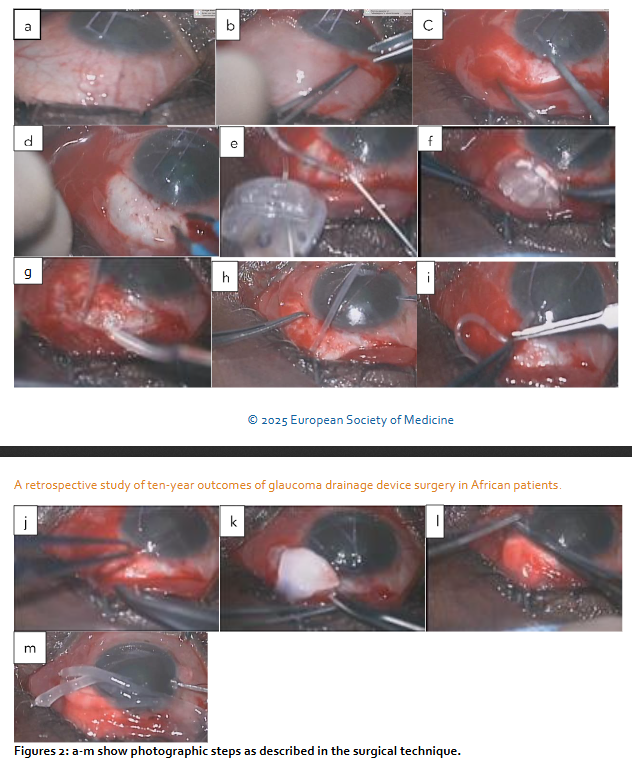

Surgical technique

Most glaucoma surgeries were done by AO, few by GIN during surgical training under direct supervision. Three were done by other surgeons during a symposium surgical skill transfer in 2019. There are basically 14 steps in the technique. Corneal traction with 6/0 vicryl after the routine cleansing draping and eyelid opening with speculum. Fornix based conjunctival peritomy to include superior and lateral rectus muscles, or temporal and inferior or medial and inferior or medial and superior for supero-temporal, infero-temporal, inferonasal, supero-nasal placement of the implant respectively. The tubes were primed with Balanced Salt Solution (BSS) to ensure patency avoiding touching the valve in AGV. The Baerveldt, ADDI and ACP were ligated with 7/0 vicryl absorbable suture to stop the flow of aqueous through the tube before a capsule is built around the plate. This is confirmed by flushing the tube after tying off to ensure complete blockage. ACP had 5/0 nylon ripcord in the lumen.

Blunt dissection was extended posteriorly separating tenon capsule from the sclera using the Westcott and conjunctival forceps. The plates were secured at 8mm or 9mm from the limbus with 9/0 or 10/0 nylon sutures. The wings of the ADDI and Baerveldt and clear path 350 were tucked under the rectus muscles. Paracentesis was created with 150 and a 23gauge needle was used to tunnel into the anterior chamber, viscoelastic or BSS was used to prevent shallow anterior chamber. The tubes were trimmed bevel up at mid iris length or 2mm into cornea and threaded through the scleral tunnel parallel to the iris plane using a tube inserter or tyer. Tubes were covered with scleral or cornea graft and secured with 10/0 suture. Conjunctiva closed water tight with 8/0 vicryl suture. Anterior chamber depth checked to ensure that tube was free from the iris and cornea. Subconjunctival injection of Genticin and Dexamethasone, Maxitriol ointment applied, speculum removed and eye padded and covered with Fox shield till following day. (1-day post-op)

Combined GDD and phacoemulsification: The first stage is as described above but the insertion of the tube into the anterior chamber and closure of the conjunctiva were done after the phacoemulsification. The second stage is a standard phacoemulsification with the intraocular lens inserted into the capsular bag using the divide and conquers technique. Post-op medication included oral antibiotics for 5 days, topical steroid and antibiotics usually tailed off over about 3/12 depending on inflammatory response, occasional mydriatic if needed for a shallow anterior chamber and IOP lowering medication as necessary.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients: A total of 243 patients, 159 (65.4%) males and 84 (34.6%) females with highest number between 61 and 80 years, mean 62.49±14.32.

| Variables | Frequency | Per cent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 84 | 34.6 |

| Male | 159 | 65.4 | |

| Total | 243 | 100.0 | |

| Age Group (years) | <21 | 3 | 1.2 |

| 21 – 40 | 13 | 5.4 | |

| 41 – 60 | 73 | 30.0 | |

| 61 – 81 | 137 | 56.4 | |

| 81 -92 | 17 | 7.0 | |

| Mean Age (Mean±SD) | 62.49 ± 14.32 years | ||

| Diagnosis in each eye | POAG | 174 | 61.5 |

| POAG + Cataract | 54 | 19.1 | |

| Traumatic Glaucoma | 15 | 5.3 | |

| Retinal-related Glaucoma (Neovascular glaucoma, Retina vein occlusion, diabetic retinopathy, retinal detachment) | 24 | 8.5 | |

| Uveitic glaucoma | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Pseudoaphakic glaucoma | 8 | 2.8 | |

| Angle closure glaucoma | 5 | 1.8 | |

| Juvenile open angle glaucoma | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Total | 283 | 100 | |

| Patient’s operated eye | Right | 115 | 47.3 |

| Left | 89 | 36.6 | |

| Bilateral | 39 | 16.1 | |

| Total | 243 | 100 | |

| Type of surgery in each eye | GDD only | 259 | 91.5 |

| GDD +Phaco +IOL | 20 | 7.1 | |

| GDD + Phaco | 2 | 0.7 | |

| GDD + Vitrectomy | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Total | 283 | 100.0 |

Other clinical parameters: FP7 had the highest number used 191 (67.5%), followed by AADI 30 (10.6%). NIL represents the unidentified type of tube used. A total of 25 (8.8%) eyes had previous cataract surgeries. 6% had previous combined cataract and glaucoma surgeries, 5.7% had previous trabeculectomy, another 5.7% had previous vitrectomy and 2.1% had intravitreal injection. Concerning laser therapy, 6.3% of patients had transscleral G-Probe cyclophotocoagulation. 3.9% had laser trabeculoplasty.

| Variables | Frequency | Per cent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of GDD | FP7 | 191 | 67.5 |

| AADI 350 | 30 | 10.6 | |

| CP350 | 22 | 7.8 | |

| CP250 | 16 | 5.7 | |

| FP8 | 11 | 3.9 | |

| CP? | 1 | 0.4 | |

| FP | 1 | 0.4 | |

| PH55 | 1 | 0.4 | |

| NIL | 10 | 3.5 | |

| Total | 283 | 100.0 |

Pre-GDD ocular surgery: Phacoemulsification 25 (8.8%), Combined Phaco + trabeculectomy 17 (6.0%), Trabeculectomy 16 (5.7%), Vitrectomy 16 (5.7%), Intravitreal Injection 6 (2.1%).

Pre-GDD Laser: G-probe trans-scleral cyclophotocoagulation 18 (6.3%), Trabeculoplasty 11 (3.9%), Laser iridotomy 2 (0.7%).

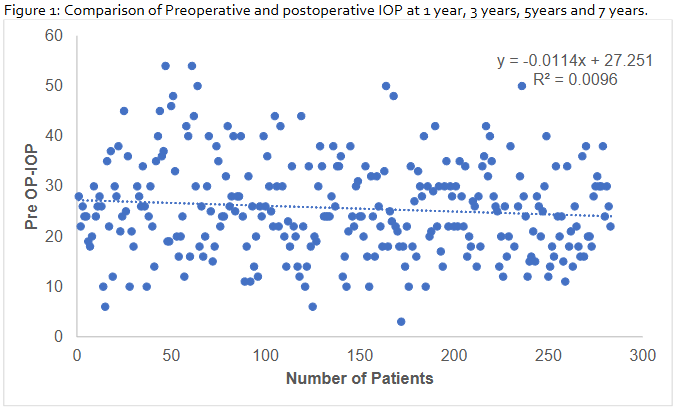

Preoperative and postoperative intraocular pressure and topical antiglaucoma medications: The mean postoperative intraocular pressure showed statistically significant drop from the mean preoperative intraocular pressure at 1 year, 3 and 5 years. The intraocular pressure in majority of the patients was below 18mmHg at 1 year, 3 and 5 years.

| Variable | N | Mean ± SD | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical antiglaucoma | Preoperative | 264 | 3.67±1.04 | |

| Postoperative | 252 | 1.78±1.25 | ||

| Intraocular pressure (IOP) | Preoperative IOP | 280 | 25.64±9.49 | |

| Year 1 | 84 | 12.85±9.29 | <0.001* | |

| Year 3 | 49 | 11.69±8.10 | <0.001* | |

| Year 5 | 17 | 13.78±7.25 | <0.001* | |

| Year 7 | 3 | 15.33±6.51 | 0.055 |

*p-value is significant at ≤0.005

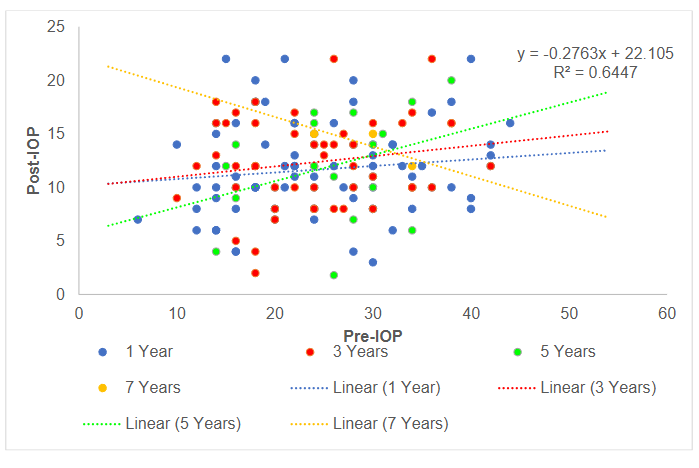

Following GDD implantation, postoperative intraocular pressure (IOP) demonstrated a significant reduction relative to preoperative levels across all follow-up periods. At 1 year, postoperative IOPs remained consistently low with minimal variability, and the regression line indicated effective pressure control irrespective of baseline IOP. By 3 to 5 years, however, a modest upward trend emerged, with higher preoperative IOP values increasingly associated with higher postoperative levels, suggesting gradual attenuation of surgical efficacy. At 7 years, the relationship shifted, with patients presenting with higher baseline IOP maintaining relatively lower postoperative pressures, though outcome variability widened substantially. The overall regression (y = –0.276x + 22.105, R² = 0.645) confirmed that higher preoperative IOP was generally associated with greater absolute reductions, but long-term follow-up revealed heterogeneous outcomes and evidence of late attrition in IOP control.

The scatter plot (figure 2) of preoperative intraocular pressure (IOP) across 280 patients shows a wide distribution (10–50 mmHg) without a discernible trend. Linear regression analysis revealed a negligible negative slope (y = –0.0114x + 27.251) with an R² value of 0.0096, indicating no meaningful association between patient sequence and preoperative IOP.

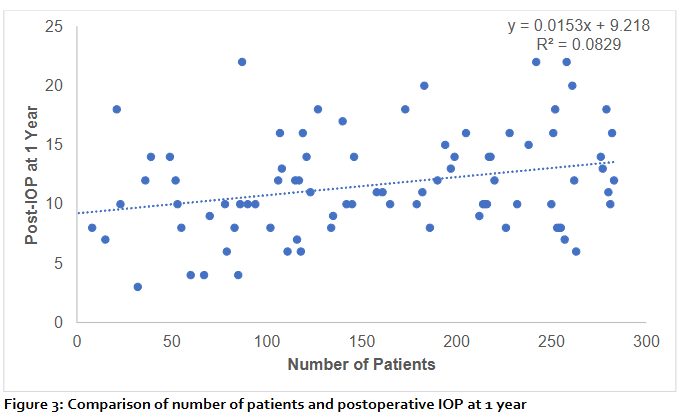

The scatter plot (figure 3) demonstrates the relationship between the number of patients and mean postoperative intraocular pressure (IOP) at 1 year. A weak positive correlation was observed, with the regression line indicating a minimal increase in IOP as the number of patients increased (y = 0.0153x + 9.218). The coefficient of determination (R² = 0.0829) shows that only 8.3% of the variation in postoperative IOP could be explained by the number of patients, suggesting that the association is weak and likely influenced by other clinical factors. The wide dispersion of data points around the regression line further highlights the variability in outcomes.

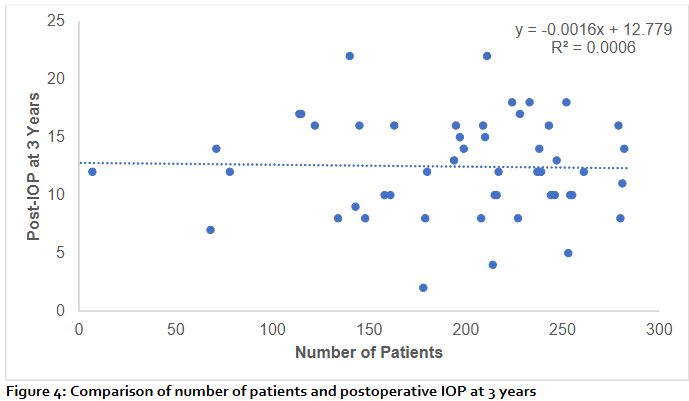

The scatter plot (figure 4) illustrates the relationship between the number of patients and mean postoperative intraocular pressure (IOP) at 3 years. The regression analysis showed no significant association, with a near-flat regression line (y = –0.0016x + 12.779). The coefficient of determination (R² = 0.0006) indicates that the number of patients accounted for less than 0.1% of the variability in postoperative IOP. These findings suggest that long-term postoperative IOP outcomes at 3 years were not influenced by patient number, and the observed variability is more likely attributable to other clinical or surgical factors.

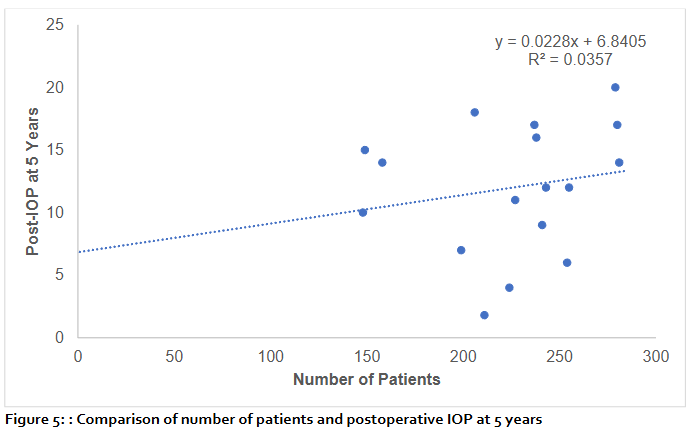

At 5 years, scatter plot (figure 5) analysis of postoperative intraocular pressure (IOP) against the number of patients showed no significant correlation. Linear regression yielded the equation y=0.0228x+6.8405 with a coefficient of determination R²=0.0357, indicating that only 3.6% of the variability in IOP outcomes was attributable to sample size. Although the regression line demonstrated a slight positive slope, the wide dispersion of values around the line underscores that the number of patients had minimal influence on long-term postoperative IOP. These findings suggest that interindividual clinical factors, rather than cohort size, predominantly determine 5-year IOP outcomes.

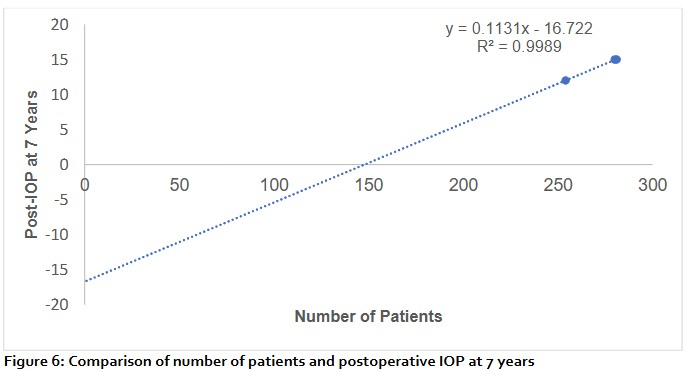

At 7 years postoperatively, a linear regression model (figure 6) demonstrated a strong linear relationship between the cumulative number of patients and mean intraocular pressure (IOP) (y = 0.1131x – 16.722, R² = 0.9989). While the model shows a nearly perfect fit, the association primarily reflects cumulative averaging rather than a true biological effect, as patient number itself does not directly influence IOP. This finding highlights the steady upward trend in IOP observed at long-term follow-up after glaucoma drainage device implantation.

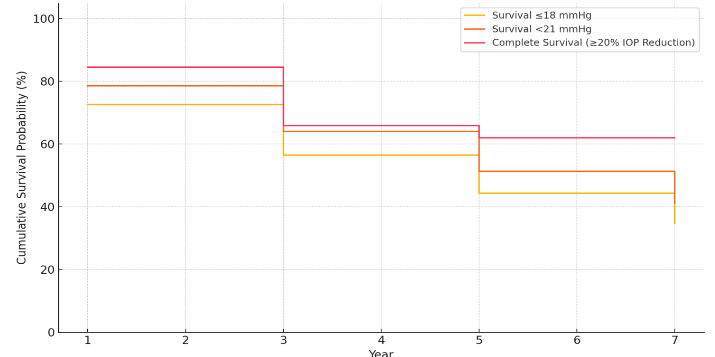

Success rate: Qualified success was achieved in 78.6%, 86.0%, 82.4% and 66.7% at 1year, 3, 5, and 7 years respectively with IOP at <21mmHg. Qualified success was achieved in 72.6%, 82.0%, 76.5% and 66.7% at 1 year, 3, 5, and 7 years respectively with IOP ≤18mmHg. Complete success was achieved in 84.5%, 78.0%, 94.1%, 100% in 1year, 3, 5, and 7years respectively at IOP reduction of more than 20% from preop IOP.

The Kaplan–Meier analysis indicates a progressive decline in surgical success over time. Survival rates were highest when success was defined as a ≥20% IOP reduction from baseline, with nearly two-thirds of eyes maintaining success at 7 years. In contrast, stricter absolute IOP thresholds (≤18 mmHg and <21 mmHg) showed lower long-term survival, with less than half of eyes maintaining IOP control by year 7. These findings highlight that while the majority of eyes initially achieved adequate IOP control, long-term attrition in surgical success is evident, particularly under stricter IOP criteria. Survival probability declined over time, with higher long-term success observed when success was defined by relative IOP reduction compared with absolute IOP thresholds.

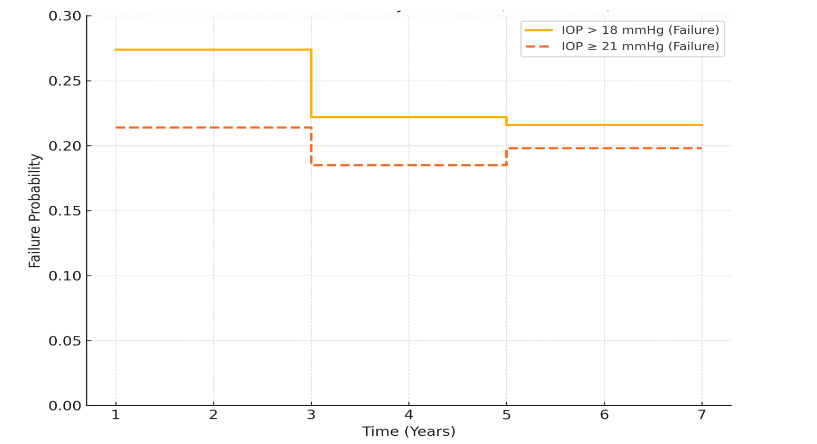

The cumulative probability of failure analysis shows that most failures occurred within the first three years postoperatively, after which the risk of additional failure plateaued. Failure rates were higher when stricter IOP control (≤18 mmHg) was used as the definition, whereas more lenient criteria (<21 mmHg) yielded lower long-term failure probabilities.

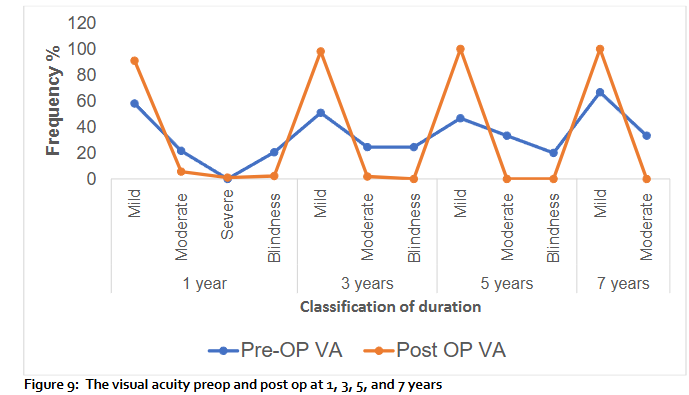

Comparison of the Pre-and postoperative visual acuity: The visual acuity improved in 30 eyes (34%) at 1 year 58 eyes (66%) maintained the same vision. At 3 years, 25 eyes (47%) had improvement in vision, 28 eyes (53%) maintained their vision. At 5 years, 8 eyes (53%) had improvement in vision, 7 eyes (47%) maintained the same vision. At 7 years vision improved in 33% and 67% maintained the same vision. There was no loss in vision.

Additional lasers and surgeries done: G-Probe transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation 7.8%. Transscleral micropulse laser cyclophotocoagulation 2.8%, selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) 1.1%. Panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) and YAG Laser capsulotomy were not pressure related. Phacoemulsification was the commonest of the surgeries with 12.4%, followed by anti VEGF intravitreal injections with 4.6%. Others were anterior chamber (AC) deepening 2.8%, removal of tube 2.5%, corneal transplant, strabismus surgery 1.1%, macula hole and ptosis surgeries 0.7% each, vitrectomy and conjunctival repair with 0.4% each.

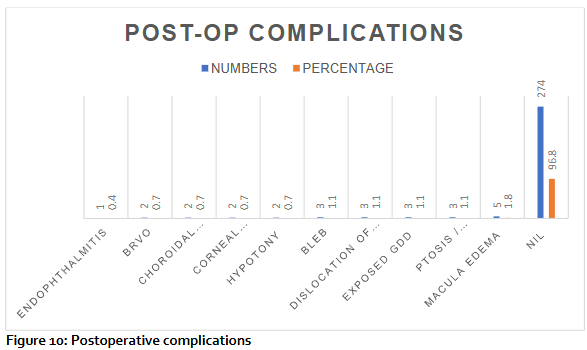

Postoperative complications: 96.8% did not have complications, macula edema was 5%, ptosis, exposed GDD, dislocation of tube and encapsulated bleb occurred in 1.1% each. Hypotony, choroidal effusion and branch retinal vein occlusion occurred in 0.7% of cases. Endophthalmitis occurred in 0.4% of cases.

Discussion

Glaucoma drainage devices are frequently employed to reduce intraocular pressure (IOP) in patients with challenging forms of glaucoma, either as a primary surgical approach or following the failure of conventional filtration procedures. Increased experience with these devices, along with advancements in their material design and surgical implantation techniques, have contributed to their growing use in recent years.

The Trabeculectomy Versus Tube (TVT) study demonstrated a sustained treatment advantage of tube shunt surgery over trabeculectomy over a 5-year follow-up period. After 5 years, the cumulative failure rate was 29.8% in the tube group compared to 46.9% in the trabeculectomy group. The disparity between the findings of the TVT study and the present study may be attributed to several factors. The TVT study was a multicenter trial conducted primarily in a North American population, whereas this study was single-center, predominantly performed by a single surgeon, and focused on an African patient population. Anatomical and physiological differences in African eyes, including thicker sclera and potentially more aggressive wound healing may influence surgical outcomes and affect the long-term success of both tube shunt surgery and trabeculectomy.

Study design differences also likely contributed to the observed disparity. The multicenter nature of the TVT study provided greater generalizability and reduced potential bias from individual surgical technique, while the standardized approach in this study ensures procedural consistency but may limit external validity. Variations in postoperative management protocols and the type or technique of tube implantation could further account for differences in cumulative failure rates.

In this study, the cumulative probability of failure with IOP <21 mmHg was 21.0% at 1 year, 19.0% at 3 years, 20.0% at 5 years and 20% at 7 years. Using a stricter IOP threshold of <18 mmHg, the cumulative probability of failure increased to 27% at 1 year, 22.2% at 3 years, 21.6% at 5 years and 21.6% at 7 years. These findings highlight that lower IOP targets are associated with a higher proportion of eyes classified as failures, a factor that may partly explain differences compared with the TVT study outcomes.

Additionally, differences in sample size and follow-up duration between the studies may explain some of the variation. The TVT study had a larger cohort, offering more statistical power, whereas this study’s smaller sample may show more variability in outcomes. Despite these differences, the present findings continue to support the long-term efficacy of tube shunt surgery in controlling intraocular pressure, while highlighting the need to consider regional and demographic factors when planning glaucoma surgery and counseling patients.

In the Primary Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (PTVT) Study, researchers assessed the 1-year failure rates of two glaucoma surgeries: tube shunt implantation and trabeculectomy with mitomycin C. Using a definition of failure as IOP ≥21 mmHg or a reduction of less than 20% from baseline on two consecutive visits after three months, the study found that the cumulative probability of failure at one year was 20.6% for the tube group and 9.6% for the trabeculectomy group. In the present study, the 1-year cumulative probability of failure for tube shunt surgery was 21.4% when using IOP <21 mmHg, and increased to 27.4% when a stricter target of IOP <18 mmHg was applied. This demonstrates that the index study’s outcomes are broadly comparable to the PTVT results when similar IOP criteria are used, but that stricter IOP targets naturally result in higher observed failure rates.

In this study, the number of glaucoma medications decreased from 3.67 preoperatively to 1.78 postoperatively, with ranges of 1.00–6.00 and 0.00–5.00, respectively. Similarly, Konstantine Purtskhvanidze et al. reported a reduction in the number of medications from 3.5 ± 1.1 (range 1–5) preoperatively to 1.6 ± 1.5 (range 0–5) postoperatively. The results of this study demonstrate a significant reduction in the number of glaucoma medications following tube shunt surgery, with the mean number decreasing from 3.67 preoperatively to 1.78 postoperatively. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Konstantine Purtskhvanidze et al., who observed a reduction from 3.5 ± 1.1 preoperatively to 1.6 ± 1.5 postoperatively. The similarity between the studies suggests that tube shunt surgery provides a reliable and reproducible decrease in medication burden across different populations. Clinically, this reduction is important as it may improve patient adherence, reduce ocular surface toxicity, and enhance quality of life. Although most patients experienced a substantial decrease in medication use, the postoperative ranges in both studies indicate that some patients still require multiple medications, reflecting individual variability in response and the severity of underlying glaucoma.

It has been suggested that postoperative inflammation and cytokine release following cataract surgery could potentially stimulate scarring and thicken the fibrous capsule around the endplate, thereby increasing intraocular pressure (IOP). However, studies have reported no significant differences in IOP, the number of glaucoma medications, or the rate of surgical failure three years after glaucoma drainage device (GDD) implantation, regardless of lens status or whether cataract surgery was performed subsequently. Some patients may still require additional glaucoma medications to maintain adequate IOP control, and a small proportion may need repeat glaucoma surgery. In the present study, all patients who underwent GDD implantation, including those with combined GDD and phacoemulsification with intraocular lens (IOL) placement, and those with GDD combined with vitrectomy were reviewed. The success rate was not significantly influenced by lens status, although this aspect could be explored further in future studies.

In this study, vision was negatively impacted by progressing cataract, corneal opacity, change in refractive state. However, improvement in vision may be attributed to clearer cornea as a result of better IOP control, cataract surgery with Intraocular lens implant, glasses correction and penetrating keratoplasty (PKP). It is noted that temporary changes in IOP do not significantly disrupt stromal hydration, elevated IOP levels and impaired endothelial function can speed up the onset and worsening of epithelial edema. Corneal changes resulting from edema impact clinical refraction, and these alterations may last for up to three months post-surgery, likely due to ongoing modifications in the corneal refractive index and central corneal thickness (CCT). These changes can degrade visual quality, as a result of compromised transparency.

Similar to trabeculectomy, tube shunt surgery also increases the risk of cataract formation and its progression. The onset of cataracts is a major contributor to vision loss after tube shunt surgery, according to findings from the Tube versus Trabeculectomy Study. In most cases, phacoemulsification in glaucomatous eyes with a functioning Baerveldt tube shunt improved vision and maintained IOP control.

The visual acuity (VA) improved in 30 eyes (34%) at 1 year, 58 eyes (66%) maintained the same vision. At 3 years, 25 eyes (47%) had improvement in vision, 28 eyes (53%) maintained their vision. At 5 years, 8 eyes (53%) had improvement in vision, 7 eyes (47%) maintained the same vision. At 7 years vision improved in 33% and 67% maintained the same vision. There was no loss in vision. The improvement in VA may be due to cataract surgery (phacoemulsification), 12.4% had phacoemulsification, 4.5% had anti-VEGF, 1.1% had corneal transplants (PKP & DSEK).

Glaucoma drainage devices may lead to a range of postoperative complications. The early complications are akin to those observed in other filtration surgeries and may include flat anterior chambers, hypotony, choroidal effusion and choroidal haemorrhage. Corneal decompensation, squint and macula edema usually occur as late complications. Hypotony due to excessive filtration is a rare complication following glaucoma drainage device GDD surgery. Hypotony and choroidal effusion typically arose from factors like wound leaks, inflammation, premature tube ligature autolysis and over-filtration from needling previous trabeculectomy. Shallow anterior chambers were treated with cycloplegics. If there was contact between the lens and cornea, a viscoelastic agent was injected to reform the anterior chamber in 2.8% of subjects. Choroidal effusions that occurred were treated with corticosteroids and cycloplegic medications with good resolutions and no surgical intervention. 96.8% did not have complications, macula edema was 5%, ptosis, exposed GDD, dislocation of tube and encapsulated bleb occurred in 1.1% each. Corneal decompensation, hypotony, choroidal effusion and branch retinal vein occlusion occurred in 0.7% of cases each. Tube exposure occurred in 1.1% of the cases, which was managed with conjunctival repair with or without removing the tube. Endophthalmitis occurred in 0.4% of cases.

Overall, the index study demonstrated a lower incidence of most complications compared to the TVT study, particularly persistent corneal edema, cystoid macular edema, and tube-related complications such as erosion or obstruction. This disparity may reflect differences in patient demographics, surgical technique, follow-up duration, or the predominance of a single experienced surgeon in the index study. Despite these differences, serious complications such as endophthalmitis were rare in both studies, supporting the relative safety of tube shunt surgery.

The hypertensive phase (HP) following glaucoma drainage device (GDD) surgery typically arises within the first 1 to 3 months postoperatively, most often between 2 to 6 weeks. It is marked by a rise in intraocular pressure (IOP) after an initial drop, unrelated to mechanical failure or blockage of the implant. This phase is especially common in valved implants, such as the Ahmed Glaucoma Valve (AGV), and may resolve on its own or require medical treatment. In our study, hypertensive phase was managed with needling the bleb, intraocular pressure lowering medications and few cases required trans-scleral Diode laser or Micropulse laser cyclophotocoagulation.

This study has several limitations, primarily its retrospective design and the loss of multiple patients before completing the ten-year follow-up. This attrition can be attributed to demographic characteristics: over 50% of patients were older than 60 years, and 7% were between 81 and 92 years. Many had multiple comorbidities, which may have limited their ability to attend regular follow-up visits due to financial constraints. Additionally, life expectancy in Nigeria is less than 60 years likely contributing to reduced long-term follow-up. Some patients also chose to continue care with local ophthalmologists due to the burden of long-distance travel. Finally, the out-of-pocket nature of medical care in the sub-Saharan African context may have influenced patient adherence, follow-up attendance, and access to medications or subsequent interventions, further affecting long-term outcome assessment. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into the efficacy and safety of tube shunt surgery in this specific population.

Although glaucoma drainage devices (GDDs) have been studied previously in sub-Saharan Africa, these studies included small sample sizes and had short-term follow-up periods. Unlike prospective studies, which are better suited for documenting both early and late complications in detail, retrospective studies such as this may underreport late complications due to incomplete follow-up and data loss over time.

The strength of this study lies in its single-center design with a mostly single experienced surgeon which ensured consistency in surgical technique as well as the relatively large sample size and extended duration of follow-up, offering valuable insights into long-term outcomes in this under-represented African population. In addition, the inclusion of a variety of glaucoma subtypes, including refractory cases, reflects clinical reality and increases the relevance of the findings for tertiary glaucoma care in similar settings. The study has the potential to significantly influence surgical practice in the sub-Saharan African region by enhancing the management strategies employed by ophthalmic surgeons.

Conclusion

This study provides long-term follow-up data on glaucoma drainage device (GDD) implantation in an African patient population, a group in which such outcomes are relatively understudied. Our findings demonstrate that GDD surgery achieves high success rates in controlling intraocular pressure, with a substantial reduction in the need for glaucoma medications, even over extended periods. Complication rates were low, supporting the safety of these devices in this setting. These results not only confirm the effectiveness of GDD surgery for recalcitrant glaucoma but also highlight its potential to influence surgical practice patterns in sub-Saharan Africa. Enhancing surgeon expertise and expanding access to GDD procedures, as facilitated through collaborations with Cure Glaucoma Foundation and New World Medical, can further improve patient outcomes. Overall, this study reinforces GDD implantation as a reliable and safe surgical option for glaucoma management in this population.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement:

No financial disclosure.

Acknowledgements:

No acknowledgements.

References:

- Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, et al. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081-2090.

- Flaxman SR, Bourne RR, Resnikoff S, et al. Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990–2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(12):e1221-e1234.

- Kyari F, Abdull MM, Bastawrous A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for blindness and visual impairment among adults in a rural Nigerian community: the Nigeria National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e008415.

- Budenz DL, Barton K, Whiteside-de Vos J, et al. Prevalence of glaucoma in an urban West African population: the Tema Eye Survey. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(5):651-658.

- Rojananuangnit K, Jiaranaisilawong P, Rattanaphaithun O, Sathim W. Surgical outcomes of glaucoma drainage device implantation in refractory glaucoma patients in Thailand. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022;16:4163-4178. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S393730.

- Arora KS, Robin AL, Corcoran KJ, Corcoran SL, Ramulu PY. Use of various glaucoma surgeries and procedures in Medicare beneficiaries from 1994 to 2012. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(8):1615-1624. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.04.015.

- Massote JA, Oliveira VDM, Cronemberger S. Glaucoma drainage devices. Rev Bras Oftalmol. 2022;81:e0041.

- Pathak-Ray V. Primary implantation of glaucoma drainage device in secondary glaucoma: Comparison of Aurolab aqueous drainage implant versus Ahmed glaucoma valve. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2025;73(Suppl 2):S327-S333. doi:10.4103/IJO.IJO_2505_23.

- Purtskhvanidze K, Saeger M, Treumer F, Roider J, Nölle B. Long-term results of glaucoma drainage device surgery. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19:14. doi:10.1186/s12886-019-1027-z.

- Ang B, Lim BCH, Betzler BK, et al. Recent advancements in glaucoma surgery—a review. Bioengineering. 2023;10(9):1096. doi:10.3390/bioengineering10091096.

- Arora KS, et al. Use of various glaucoma surgeries and procedures in Medicare beneficiaries from 1994 to 2012. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(8):1615-1624.

- Hong CH, Arosemena A, Zurakowski D, Ayyala RS. Glaucoma drainage devices: a systematic literature review and current controversies. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50(1):48-60. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.10.006.

- Gedde SJ, Singh K, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ. Tube versus trabeculectomy study group. The tube versus trabeculectomy study: interpretation of results and application to clinical practice. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:118–126.

- Gedde SJ, Feuer WJ, Shi W, et al. Treatment outcomes in the Primary Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study after 1 year of follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(5):650-663. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.02.003.

- Wong SH, Radell JE, Dangda S, et al. The effect of phacoemulsification on intraocular pressure in eyes with preexisting glaucoma drainage implants. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2021;4(4):350-357. doi:10.1016/j.ogla.2020.11.006.

- Stallworth JY, Hekmatjah N, Yu Y, et al. Effect of lens status on the outcomes of glaucoma drainage device implantation. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2024;7(3):242-250. doi:10.1016/j.ogla.2024.01.004.

- Sa HS, Kee C. Effect of temporal clear corneal phacoemulsification on intraocular pressure in eyes with prior Ahmed glaucoma valve insertion. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:1011–1014.

- Gujral S, Nouri-Mahdavi K, Caprioli J. Outcomes of small incision cataract surgery in eyes with preexisting Ahmed glaucoma valves. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:911–913.

- Ytteborg J, Dohlman CH. Corneal edema and intraocular pressure: II. Clinical results. Arch Ophthalmol. 1965;74(4):477–484. doi:10.1001/archopht.1965.00970040479008.

- Díez-Ajenjo MA, Luque-Cobija MJ, Peris-Martínez C, et al. Refractive changes and visual quality in patients with corneal edema after cataract surgery. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022;22:242. doi:10.1186/s12886-022-02452-0.

- Gedde SJ, Herndon LW, Brandt JD, et al. Postoperative complications in the Tube versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) study during five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:804–814.

- Erie JC, Baratz KH, Mahr MA, Johnson DH. Phacoemulsification in patients with Baerveldt tube shunts. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32(9):1489-1491.

- Hille K, Moustafa B, Hille A, Ruprecht KW. Drainage devices in glaucoma surgery. Klinika Oczna. 2004;106(4/5):670-681.

- Lloyd MA, Baerveldt G, Fellenbaum PS, et al. Intermediate-term results of a randomized clinical trial of the 350- versus 500-mm² Baerveldt implant. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(8):1456-1464. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(94)31152-3.

- Heuer DK, Lloyd MA, Abrams DA, et al. Which is better? One or two? A randomized clinical trial of single-plate versus double-plate Molteno implantation for glaucomas in aphakia and pseudophakia. Ophthalmology. 1992;99(10):1512-1519. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(92)31772-5.

- Ayyala RS, Zurakowski D, Monshizadeh R, et al. Comparison of double-plate Molteno and Ahmed glaucoma valve in patients with advanced uncontrolled glaucoma. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2002;33:94-101.

- Stein JD, McCoy AN, Asrani S, et al. Surgical management of hypotony owing to overfiltration in eyes receiving glaucoma drainage devices. J Glaucoma. 2009;18(8):638-641.

- Levinson JD, Giangiacomo AL, Beck AD, et al. Glaucoma drainage devices: Risk of exposure and infection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(3):516-521.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.05.025.

- Gedde SJ, Scott IU, Tabandeh H, et al. Late endophthalmitis associated with glaucoma drainage implants. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(7):1323-1327. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00598-X.

- Myers JS, Lamrani R, Hallaj S, et al. 10-Year clinical outcomes of tube shunt surgery at a tertiary care center. Am J Ophthalmol. 2023;253:132-141. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2023.04.001.

- Law SK, Kornmann HL, Giaconi JA, et al. Early aqueous suppressant therapy on hypertensive phase following glaucoma drainage device procedure: A randomized prospective trial. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(3):248-257. doi:10.1097/IJG.0000000000000131.

- Tang M, Gill N, Tanna AP. Incidence and outcomes of hypertensive phase after glaucoma drainage device surgery. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2024;7(4):345-351. doi:10.1016/j.ogla.2024.03.006.

- Fargione RA, Tansuebchueasai N, Lee R, Tai TYT. Etiology and management of the hypertensive phase in glaucoma drainage-device surgery. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019;64(2):217-224. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.09.006.

- Omoti AE, Enock ME, Iyasele ET. Surgical management of primary open-angle glaucoma in Africans. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2010;5(1):95-107. doi:10.1586/eop.09.66.

- Gessesse G. The Ahmed glaucoma valve in refractory glaucoma: Experiences in Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2015;25:267-272. doi:10.4314/ejhs.v25i3.10.

- Kiage DO, Gradin D, Gichuhi S, Damji KF. Ahmed glaucoma valve implant: experience in East Africa. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2009;16(3):151-155. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.56230.