Minimally Invasive Surgery for Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

Minimally Invasive Cost-Effective Surgical Treatment of Lumbar Spondylolisthesis with Associated Spinal Stenosis

Miguelangelo Perez- Cruet, M.D., M.Sc.1, Jordan Black, M.D., M.Sc.2, Ishan Singhal, M.D.2, Daniel Fahim, M.D.1

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 November 2024

CITATION: CRUET, Miguelangelo Perez- et al. Minimally Invasive Cost-Effective Surgical Treatment of Lumbar Spondylolisthesis with Associated Spinal Stenosis. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 12, n. 11, jan. 2025. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6163>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i11.6163

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

The paraphernalia surrounding the minimally invasive surgical approach for lumbar spondylolisthesis with associated spinal stenosis is reviewed. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (MI-TLIF) for patients with lumbar spondylolisthesis and associated spinal stenosis. A retrospective review of patients undergoing MI-TLIF with a single surgeon at our institution was performed to determine compliance with study parameters. Inclusion criteria included the diagnosis of Grade 1 lumbar spondylolisthesis (per Meyerding classification) with associated spinal stenosis at one level between L1-L5 on either CT myelogram or MRI lumbar spine. All patients had baseline preoperative and postoperative data evaluated using visual analog scores (VAS) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) for outcomes. Results demonstrated significant improvement in VAS and ODI scores. Only one patient required reoperation for symptomatic infection. This study supports the safety and efficacy of MI-TLIF for the treatment of lumbar spondylolisthesis with associated spinal stenosis.

Keywords

- Minimally invasive surgery

- Lumbar spondylolisthesis

- Spinal stenosis

- MI-TLIF

- Visual analog score

- Oswestry Disability Index

Introduction

Low back pain is one of the most common causes of chronic pain and disability worldwide. Studies of American adults estimate that as much as 80% of the population will suffer from back pain during their lifetime. Depending on the etiology, back pain can be managed conservatively to temper symptoms while reducing the severity and incidence of pain exacerbations; however, patients suffering from refractory lumbar spondylolisthesis with associated stenosis can be surgically treated with laminectomy and fusion using either an open or minimally invasive approach.

A disadvantage of open surgery is the need to detach paraspinous muscles from the spine and remove bone elements that are unrelated to the underlying pathology, most notably the spinous processes. These structures are vital to the long-term health of the spine and their removal can potentially lead to adjacent level pathology, scar formation, and the need for additional spine surgery. This paper describes a technique that allows for direct decompression of the spinal canal while sparing the paraspinous muscles and spinous process through a muscle dilating approach. In addition, the primary fusion material is the patient’s own morselized autograft harvested from the surgical site during decompression, which has been shown to reduce graft site morbidity, maintain cost effectiveness, and achieve high fusion rates. Using percutaneous pedicle screws in combination with a unique interbody graft cage system, most spondylolisthesis can be reduced to grade 0. This is felt to improve long-term patient-generated outcomes by restoring canal and foraminal diameter and sagittal alignment.

Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (MI-TLIF) was developed as a safer, equally effective technique for lumbar spine fusion compared to the traditionally open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF). Several benefits of the MI-TLIF have been explored in the literature. MI-TLIFs have demonstrated consistently superior short-term outcomes when compared to open TLIFs as measured by blood loss, length of hospital stay, readmission rates, and postoperative recovery time. Minimally invasive techniques also reduce opioid dependence in patients undergoing spine surgery by reducing the time spent in the in-patient setting. Procedure related adverse events are also less common following MI-TLIF compared to open TLIF, and patients treated with an MI-TLIF are more likely to report improvements in both short and long-term functional status and pain indices. Radiographically, the MI-TLIF has been shown to reduce pathological lordotic misalignment of the spine and achieve fusion with similar success as the open TLIF while minimizing blood loss.

While most of the benefits of a MI-TLIF result from the technique itself, improvements in postoperative outcomes may also be related to the innovation in instruments and technology. The MI-TLIF is commonly defined by 3 major operative features: a paramedian/lateral incision, the use of muscle dilators, and percutaneous pedicle screw instrumentation. Several contributions to the literature have explored nuances in instrument technology with the goal of improving fusion rates and patient reported outcomes while lowering rates of complication, subsidence, and pseudarthrosis. The use of expandable cages, independent blade retractor systems, unique cage configurations, tubular dilators, and percutaneous pedicle screw systems underscores the fluidity of the MI-TLIF procedure. Each of these variations seek to improve patient outcomes and fusion rates while mitigating the risk of complications. Notably, there is a relative paucity of clinical data regarding technical variations using existing technology and the impact on procedural adverse events and patient reported outcome.

This case series highlights a unique variation in the MI-TLIF instruments and technology with critical analysis of patient reported outcomes as part of an FDA IDE approved clinical trial. In this study, novel instruments and technology were developed that allow insertion of the patient’s own surgical site morselized autograft into the disc space around the

The interbody cage device. The autograft is contained by the anulus fibrosis of the disc and allows for off-loading of the cage to promote fusion via Wolff’s law, thus minimizing cage subsidence and maximizing interbody autograft implantation to promote high fusion rates.

Methods

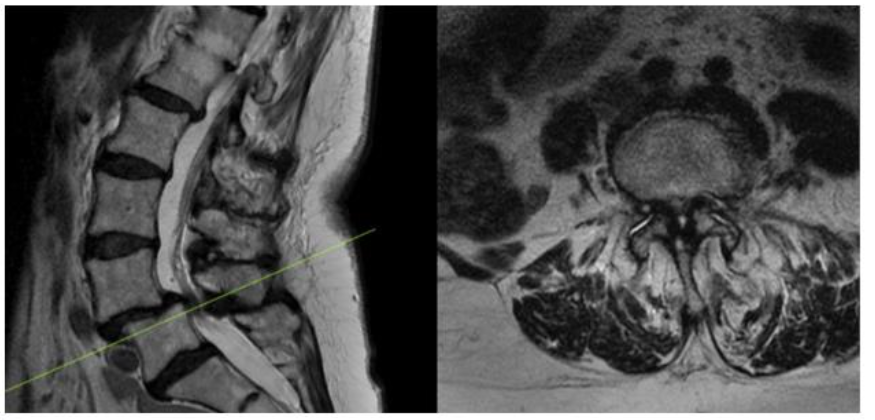

As part of an FDA approved device investigation study (NCT03115983) with Western IRB approval, between March 2016 and June 2020 all patients undergoing MI-TLIF with a single surgeon at our institution were prospectively reviewed to determine compliance with study parameters. Inclusion criteria included the presence of at least Grade 1 lumbar spondylolisthesis (per Meyerding classification) with associated spinal stenosis at one level between L1-S1 on either CT myelogram or MRI of the lumbar spine (Figure 1).

All patients had to have experienced symptoms of neurogenic claudication or lumbar radiculopathy persisting for ≥6 months despite conservative management. Baseline patient reported outcomes thresholds were ≥50/100 for VAS back scores, and ≥35/100 for ODI scores. Only skeletally mature patients between 25-80 years of age were included. Patient capacity was assessed, and after the relevant risks and benefits of the procedure were discussed, the required informed consent was obtained.

Figure 1. Preoperative MRI showing L4-5 Grade 1 Spondylolisthesis with associated stenosis

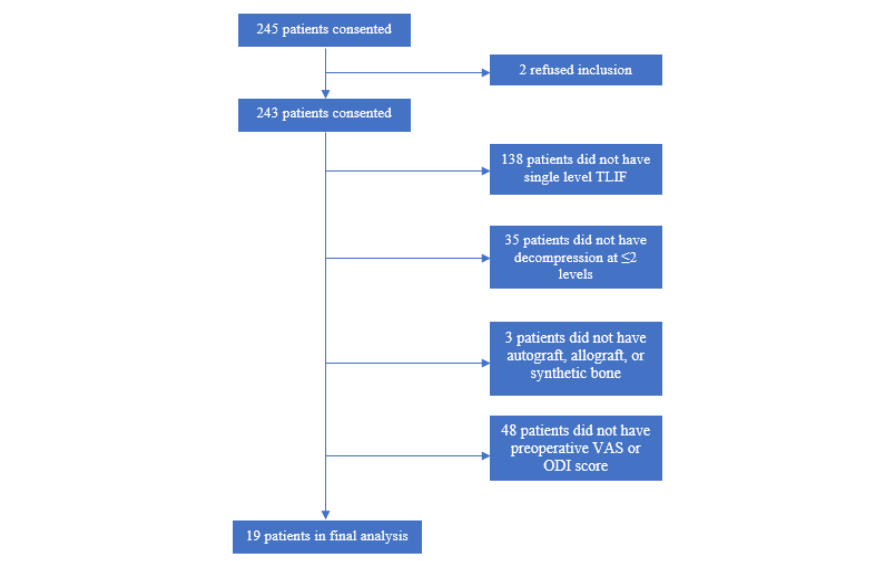

Several exclusion criteria were also outlined. Patients suffering from discogenic pain, facet mediated pain, or radicular pain without anatomical abnormalities were excluded. Patients with confounding comorbidities, including peripheral vascular disease, peripheral neuropathy unrelated to spinal stenosis, osteomalacia or osteoporosis were excluded. Patients who had suffered previous back injury or had undergone any operative procedure at the level of treatment were excluded. Patients with degenerative scoliosis with a Cobb angle >10° or ankylosed segment at the operative level were excluded. Patients who were allergic to titanium or polyethylene or actively receiving immunomodulatory medications were ineligible. Morbidly obese patients (BMI > 40), patients with a history of malignancy, or patients intending to become pregnant during the study period were excluded. Patients suffering from psychiatric illness or with a current/prior diagnosis of substance abuse were excluded. 245 patients were consented and underwent MI-TLIF during that time course, and after applying our inclusion and exclusion criteria, as visualized in figure 2, nineteen patients qualified for inclusion given our study parameters. Patients undergoing traditional open midline TLIF were also put through the same screening process and 140 patients were included for analysis from that cohort during the same time course. Preoperatively, beyond their initial CT myelogram and/or MRI lumbar spine all patients also were evaluated with anteroposterior, lateral, flexion, and extension X-rays of the lumbar spine, Osteoporotic Self-Assessment Tool evaluation, and if there was an history of fragility fracture they also underwent a DXA or OCT scan for further evaluation. Lumbar spine X-rays were also repeated at discharge, 6 weeks, 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months postoperatively in accordance with the FDA device investigation study protocol.

Figure 2. Flowchart illustrating MI-TLIF Patient selection details

Detailed neurological examinations, physical/medical therapy utilization, pain medication usage, leg and back pain assessments utilizing visual analog scales (VAS), Zurich Claudication Questionnaires, Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), 12-Item Short Form Health Surveys (SF-12), ability to return to work, patient overall satisfaction, and adverse events were also evaluated and recorded at 6 weeks, 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months postoperatively. Demographic, procedural, pre- and post-operative outcomes data were critically reviewed for 19 patients who underwent MI-TLIFs and TLIFs per FDA investigational device exemption (IDE) monitoring guidelines²⁶. Due to the concurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic, patient follow-up visits were transitioned from in-person office visits to scheduled telemedicine visits with visual neurological evaluations. Table 1 includes a demographic comparison of the control groups.

Due to the relatively small sample size, non-parametric Friedman ANOVA followed by Wilcoxon rank sum tests were conducted to investigate the statistical significance of functional and clinical improvements. An alpha level of 5% was used to assess statistical significance.

Table 1. Patient Demographic Data Undergoing Novel MI-TLIF versus Traditional TLIF

| Novel MI-TLIF | Traditional TLIF | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex ratio (M:F) | 7:12 | 40:100 |

| Mean Age | 65 +/- 9 | 64 +/- 9 |

| BMI | 32 +/- 6 | 30 +/- 6 |

| L4-5 index level (n, %) | 18 (95) | 120 (86) |

| L5-S1 index level (n, %) | 1 (5) | 8 (14) |

Surgical Technique

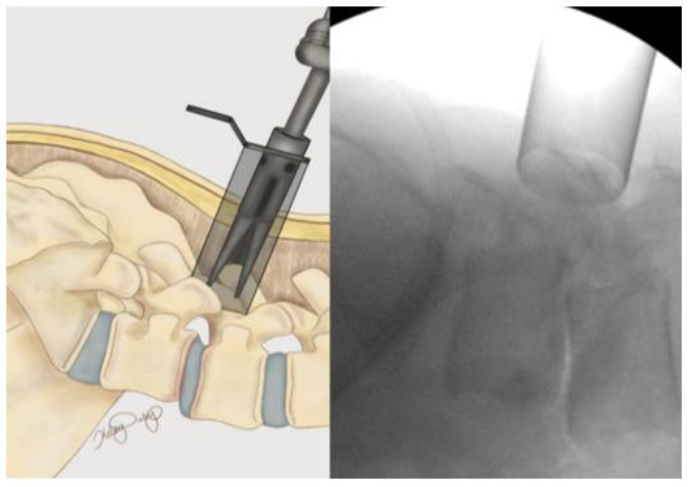

The patient is positioned prone on a spinal Jackson table, the area of interest is prepped and draped in a sterile fashion. The index level is localized utilizing lateral fluoroscopy. An incision is then made 3 cm lateral to the midline overlying the appropriate disc space. The fascia is incised parallel to the spinous processes and the One-Step-Dilator (BoneBac/Thompson MIS, Sandown, NH) is used to approach the spine in a muscle sparing fashion (Figure 3). The dilator is supported by a holder and once docked on the facet, counter clock-wise rotation opens the flanges of the dilator, separating the muscle tissue. A tubular retractor of the appropriate length is then placed over the one step dilator and the dilator is removed. The tubular retractor is attached to a support arm (Walter Arm, Zimmer Spine) which has been fastened to the operative table.

Figure 3. One-step dilator (Thompson MIS/Bonebac, Sandown, NH) placement

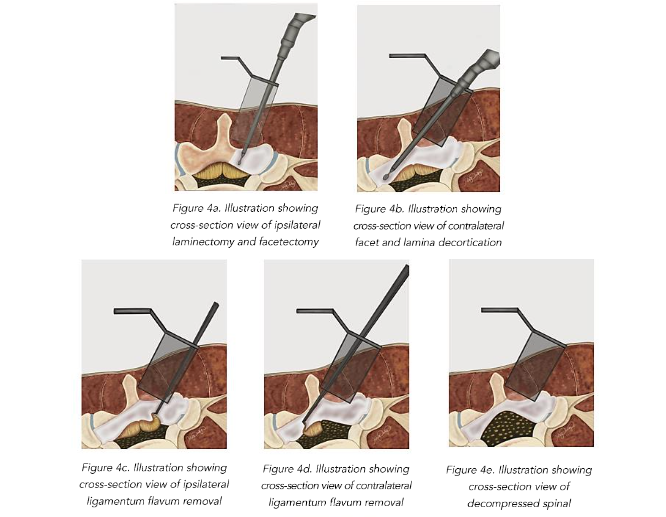

LUMBAR EXPOSURE AND DECOMPRESSION

Utilizing an operative microscope the soft tissue is removed to expose the facet complex laterally, and the ipsilateral lamina medially. A high-speed drill and M8 cutting burr are used to perform the laminectomy. All drilled bone is collected using the BoneBac™ Press (BoneBac/Thompson MIS, Sandown, NH). This bone autograft avoids graft site morbidity, has exceptional handling characteristics, and can be mixed with other bone graft material as needed. After the ipsilateral laminectomy (Figure 4A) is completed, the patient and retractor are then tilted 5–10 degrees away from the surgeon to expose the base of the spinous process and the contralateral lamina which is then undercut with a cutting burr as far as the medial border of the contralateral facet complex (Figure 4B). After adequate bony decompression has been achieved, the hypertrophied ligamentum flavum is removed bilaterally, first on the ipsilateral side (Figure 4C) and then on the contralateral side (Figure 4D) which provides improved space for safely removing the contralateral ligamentum flavum, and limits durotomy. Inspection using a ball ended micro-probe instrument assures adequate direct decompression of the spinal canal (Figure 4E).

INTERBODY FUSION

Once adequate decompression is achieved, a high-speed cutting burr is used to perform an ipsilateral facetectomy after which the disc space is identified using fluoroscopy, and an annulotomy is then performed to enter the disc space. A series of disc space reimers, curettes, and rongeurs help prepare the disc space for interbody arthrodesis. Care is taken to adequately prepare the vertebral end plates by removing the cartilaginous portions to promote arthrodesis. Once the disc space is thoroughly prepared, implant sizing is determined using the BoneBac/Thompson MIS reimers and trials.

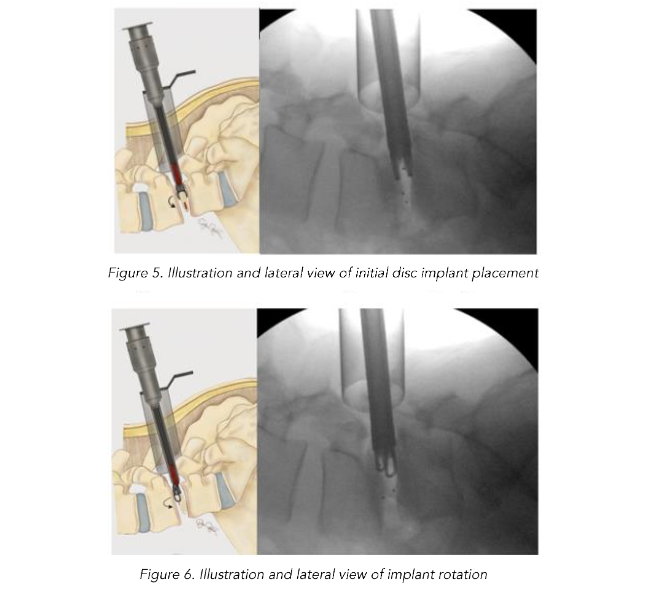

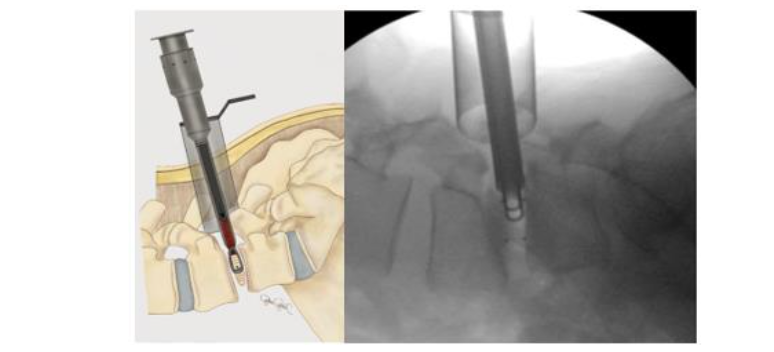

The BoneBac/Thompson MI-TLIF interbody system is an insert and rotate device. Lateral fluoroscopy identifies proper implant depth within the disc space and, once adequate depth is confirmed, the implant is rotated 90 degrees to restore disc space height and foraminal diameter (Figures 5–7). The implant is made from polyether ether ketone (PEEK) which facilitates implant rotation within the disc space and spondylolisthesis reduction as the curved surface of the implant corresponds to that of the vertebral endplates. Additionally, the soft nature of PEEK allows for an easier reduction of spondylolisthesis by limiting the frictional coefficient between implant surface and vertebral endplates. This unique design allows for easier access to the disc space as well as adequate restoration of sagittal alignment and disc height and foraminal diameter restoration after implant rotation. Moreover, larger implants can be introduced through a relatively smaller profile prior to rotation, thereby minimizing nerve root retraction and reducing the risk of nerve injury or dural tear. A torque limiting handle assures that the implant is not placed under undue forces during rotation. Once the implant is rotated, then the original bone graft injector handle can be reattached to the implant for bone graft application. Typically, an implant with dimensions of 7-mm width, 11- or 12-mm height, and 26 mm length is used in most cases. Thus the 7 mm width allows ease of placement within the disc space to rotate and restore disc height to 11- or 12-mm height.

Figure 7. Illustration and lateral view of implant after 90 degree rotation showing final implant positioning to restore disc height

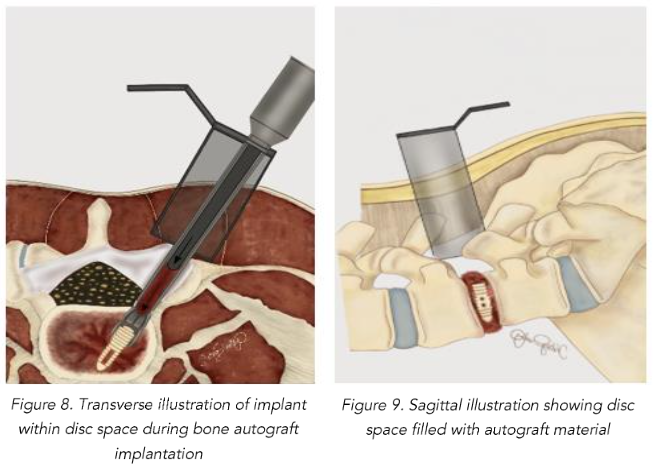

With the implant positioned properly within the disc space, BoneBac TLIF bullets are filled with morselized autograft collected from the BoneBac Press which are then loaded on top of the implant inserter T-handle, and the morselized bone graft material is pushed through the implant holder using a plunger to exit either side of the PEEK cage within the disc space (Figures 8 and 9). Typically, 10–15 bullets are used to completely fill the disc space with morselized autograft. Each bullet contains about 1.5 cc of bone graft material. If additional graft material is needed, 1–5 ccs of morselized allograft (Trinity Elite, Orthofix, Lewisville, TX) or other suitable bone graft extender is mixed with morselized autograph bone graft material. The system allows for adequate quantity of bone to be injected into the interspace to ensure compression of graft material rather than the implant itself, thereby reducing the incidence of implant subsidence and improving arthrodesis rates. After the disc space is sufficiently filled with graft material, the implant is disengaged in the disc space which is then inspected using microscope visualization and a ball-ended probe to ensure that the bone graft material is entirely within the disc space. The facet complex is then reconstructed using a combination of morselized autograft mixed with allograft material.

PERCUTANEOUS PEDICLE SCREW INSTRUMENTATION

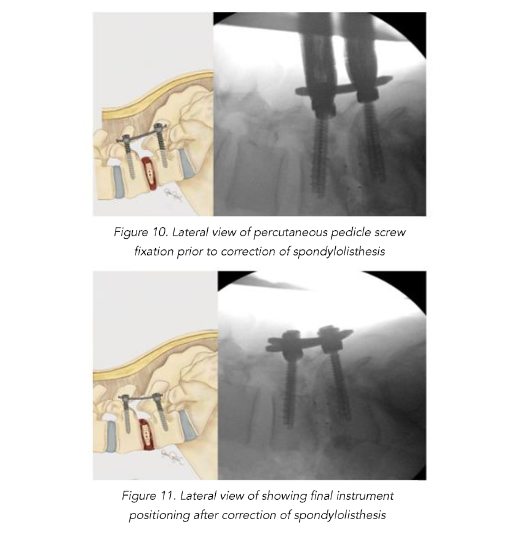

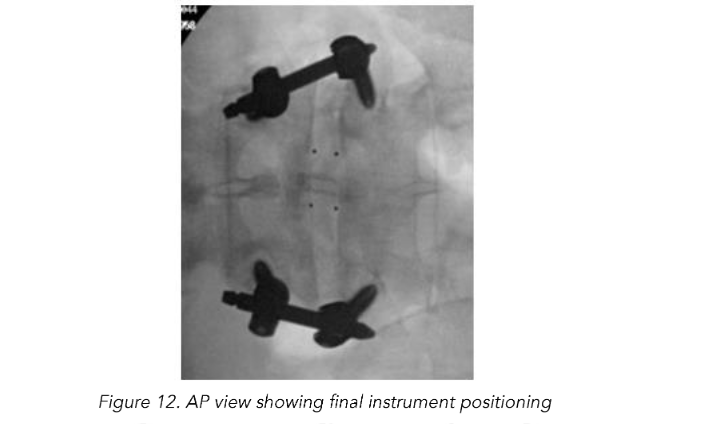

Once adequate decompression, interbody placement and complete hemostasis are achieved, the tubular retractor is removed, and an incision is made on the contralateral side, equidistant from the midline (3 cm), for the interbody fusion. AP and lateral fluoroscopy are used to target the pedicles for percutaneous pedicle screw fixation and place initial K-wires. Once the K-wires are placed they are then stimulated with concurrent neuromonitoring. A stimulation threshold less than 8 mAmps requires repositioning of K-wire or later pedicle screw. Percutaneous pedicle screws are placed bilaterally and segmentally to ensure suitable fixation to promote arthrodesis.

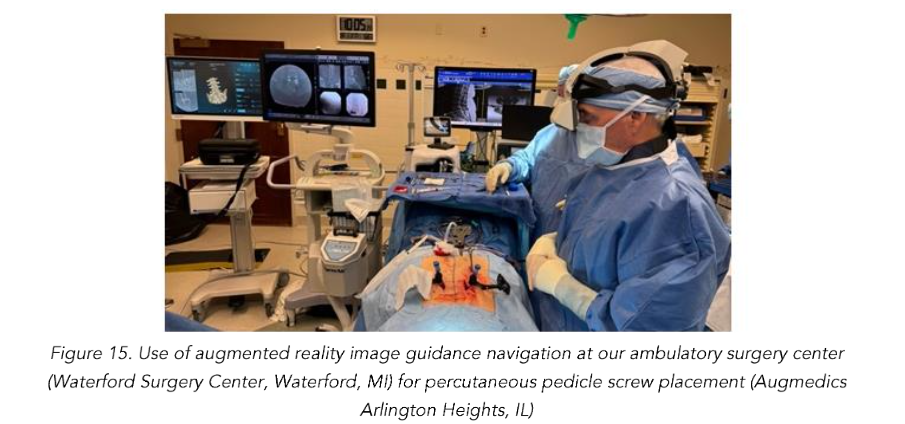

Total reduction of spondylolisthesis is performed by securing the rod to the most dorsal pedicle screw head (i.e., L5 seen in L4–5 spondylolisthesis) (Figure 10) and subsequently bringing the ventral pedicle screw head up towards the rod (Figure 11). This is done simultaneously bilaterally to reduce rotation and achieve total spondylolisthesis reduction thus restoring sagittal alignment. The advantages of this technique specifically arise from significant increases in the diameter of the neural foramen and spinal canal, and the larger surface area for fusion between adjacent vertebrae. The unique design of the PEEK Thompson MIS BoneBac TLIF device, with curved ends that correspond to the vertebral endplates, helps to facilitate reduction of the spondylolisthesis (Figures 10 and 11). Final tightening is performed, and the towers are removed allowing the paraspinous muscles to return to their normal anatomical position. Excellent long-term clinical outcomes and fusion rates using the MI-TLIF technique described have been achieved (Figures 13 and 14). More recently, but not within the patients covered in this data set, we began trialing augmented reality image guided navigation to place percutaneous pedicle screws in an effort to further reduce radiation exposure to both the patient and surgical team (Figure 15).

Results

DEMOGRAPHICS AND OPERATIVE LEVELS

Cases from the 19 patients who underwent a MI-TLIF with the described technique were included in this series. All procedures were conducted by the primary author (MPC). The mean patient age at the time of operation was 65 years (47–78 years range), and the average height and BMI were 1.65 m and 32 respectively. From the sample, 13 patients (68.4%) had no associated comorbidities as measured by the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), 4 patients (21.0%) had mild grade comorbidities (CCI scores of 1, n = 2 or 2, n = 2), and 2 patients (10.5%) had moderate grade comorbidities (CCI scores of 3, n = 2 or 4, n = 0)²⁷. Almost all procedures (18/19, 94.7%) were performed at the L4–L5 level (1 procedure was conducted at L5–S1 level). Adjacent level decompression was done at L5–S1 for 2 patients who underwent a L4–5 primary fusion. All procedures were conducted prior to August 2020.

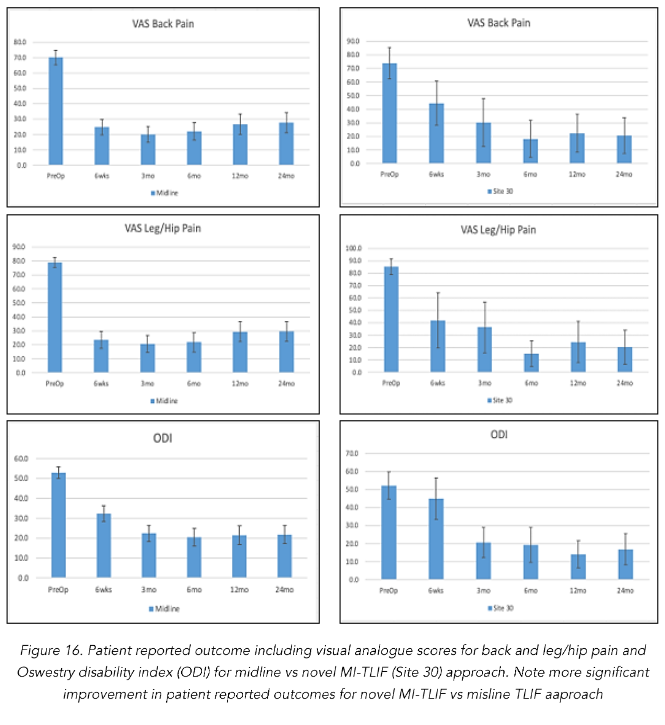

PATIENT REPORTED OUTCOMES

The procedure time (minutes), estimated blood loss (mL), and length of hospital stay (days) for MI-TLIF were 156 +/- 31, 72 +/- 32, and 2.6 +/- 1.8, respectively. Compared to traditional TLIF procedure time, estimated blood loss, and length of hospital stay were 189 +/- 78, 273 +/- 252, 3.1 +/- 1.7 (Table 2). VAS back and leg/hip pre-operatively were 79.3, 85.3, and 52.2 versus 20.6, 20.3 and 16.9 points, respectively at 2-year follow-up for novel MI-TLIF. Compared to 69.7, 78.8, and 52.7 versus 27.9, 27.8 and 22.4 at 2-year follow-up for traditional midline TLIF. These improvements were all statistically significant at the 5% level (Figure 16). Importantly, 18 of 19 MI-TLIF patients (94.7%) reported symptomatic improvement across all PRO measures at 6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year and 2-year follow-up relative to preoperative levels. One patient reported mild deterioration in VAS score relative to preoperative levels (63 at baseline, 70 at 6 weeks and 6 months), but had continuing improvements compared to baseline in ODI and worst LH scores at all follow-ups. Moreover, this patient experienced an improvement in VAS score at the 2-year follow-up visit compared to baseline.

Table 2. Patient Operative Data Undergoing Novel MI-TLIF versus Traditional TLIF

| Novel MI-TLIF | Traditional TLIF | |

|---|---|---|

| Procedure time (min) | 156 +/- 31 | 189 +/- 78 |

| EBL (ml) | 72 +/- 32 | 273 +/- 252 |

| LOS (days) | 2.6 +/- 1.8 | 3.1 +/- 1.7 |

VAS scores improved from the preoperative mean of 73.9 (SD 22.3, n=19) to 44.5 at 6 weeks (SD 29.1, n=16), and 19.1 at 6 months (SD 30.4, n=15) (Table 3). The mean VAS score increased moderately to 22.3 (SD 26.7, n=18) at 1 year compared to 6 months, but was still significantly lower than baseline. This increase in VAS scores between 6 months and 1 year follow-up was not statistically significant (p=1.000). Average VAS scores improved from the moderate/severe pain categorization preoperatively, to mild pain (VAS score 5–44mm) at 1 year follow-up²⁸. While the relative change from baseline to 6 weeks was not significant (p=.79), the changes from baseline to 6 months and baseline to 1 year of follow-up showed statistically significant improvement in VAS scores (p=.000 and p=.000 respectively). There was also a statistically significant improvement in VAS scores between the 6 week and 6 month visits (p = .034) (Fig. 14). Patient reported outcomes were better for the novel MI-TLIF compared to open TLIF approach.

Mean ODI back scores improved from a baseline of 51.3 (SD 15.0, n=19) to 45.0 at 6 weeks (SD 21.2, n=17), 18.2 at 6 months (SD 17.5, n=18), and 14.0 at 1 year of follow-up (SD 14.1, n=18) (Table 1). Overall, patients improved from subjective feelings of severe disability (ODI score 41–60) preoperatively to minimal disability (ODI score 0–20) at 1 year follow-up²⁹. Similar to the trend in VAS scores, the improvements in ODI scores from baseline to 6 weeks were not significant (p=1.000), while those from baseline to 6 months and baseline to 1 year were both statistically significant (p=.001 and p=.000 respectively). Statistically significant improvements in ODI scores were also observed between 6 week and 6-month follow-up visits as well as the 6 month and 1 year follow-up visits (p = .004 and p = .000 respectively).

PROCEDURAL DATA AND ADVERSE EVENTS

Adverse events were noted in 4/19 (21%) of MI-TLIF patients. Three patients had superficial surgical site infection (SSI) within 2 weeks of the operation, all of which were treated with oral antibiotic therapy for 7 days. All 3 patients suffered from obesity, a well described risk factor for postoperative infections³⁰. Of these 3 patients, 1 developed a SSI during their hospital stay; 2 patients both noted symptoms of SSIs 10 days after the procedure, after both had been discharged home. All surgical site infections resolved after patients were placed on appropriate oral antibiotic therapy.

Almost all (18/19, 95%) patients achieved fusion of the lumbar spine confirmed by radiographic imaging on follow-up visits. One patient required repeat fusion due to posterior cage displacement complicated by adjacent segment disease. Six months after undergoing a primary L4-5 MI-TLIF, mild retropulsion of the interbody device was noted, but the patient denied any symptomatic manifestations. The patient presented 2 years and 6 months after the primary operation with severe neurogenic claudication when standing as well as shooting pains extending down the contralateral lower right limb. At this time, the patient was found to have significant central stenosis as well as concomitant adjacent segment stenosis at L2-3 and L3-4. Adjacent level stenosis was felt to be a continuation of the patient’s underlying degenerative disc disease leading to lumbar stenosis. This patient was re-treated 2 years and 7 months after the primary procedure with a repeat MI-TLIF at the index level (L4-5) and additional laminectomy and fusion at L2-3 and L3-4 due to progressive adjacent segment disease confirmed radiographically. The patient made an unremarkable recovery.

Conclusion

The MI-TLIF technique elucidated within this paper utilizing largely mesograft-augmented stabilization during spinal element decompression, as well as a rotating static PEEK interbody graft, allows surgeons to prioritize preservation of normal anatomy while maintaining high fusion rates, minimizing biologic costs, and maximizing improvement of long-term improvement in patient reported outcomes.

Disclosures

Nick Perez-Cruet

BoneBac MIS/Boneback: Stock ownership

Thieme Publishing Inc.: Royalties

Limitations

This study has certain limitations that must be taken into consideration. First, although the patients were rigorously monitored per FDA IDE procedure guidelines, this study is a case-series allowing for limited sample size (n=19) under the parameters outlined herein.

References

1. Rubin DI. Epidemiology and risk factors for spine pain. Neurol Clin. May 2007;25(2):353-71. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2007.01.004

2. Buchbinder R, Underwood M, Hartvigsen J, Maher CG. The Lancet Series call to action to reduce low value care for low back pain: an update. Pain. Sep 2020;161 Suppl 1(1):S57-S64.

doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001869

3. The Cochrane C, van der Gaag WH, Roelofs PDDM, et al. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for acute low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020/04 2020;2020(4):CD013 581. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013581

4. The Cochrane C, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, et al. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017/06 2017;2020(2):CD007938. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007938.pub4

5. Ochs G, Struppler A, Meyerson BA, et al. Intrathecal baclofen for long-term treatment of spasticity: a multi-centre study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1989/08 1989;52 (8):933-939. doi:10.1136/jnnp.52.8.933

6. Manchikanti L, Nampiaparampil DE, Manchikanti KN, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of saline, local anesthetics, and steroids in epidural and facet joint injections for the management of spinal pain: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Surgical neurology international. 2015 2015;6(Suppl 4):S194-235.

doi:10.4103/2152-7806.156598

7. Chan AK, Bisson EF, Bydon M, et al. A Comparison of Minimally Invasive and Open Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion for Grade 1 Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis: An Analysis of the Prospective Quality Outcomes Database. Neurosurgery. 2020 2020;87(3):555-562. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyaa097

8. Li Y-B, Wang X-D, Yan H-W, et al. The Long-term Clinical Effect of Minimal-Invasive TLIF Technique in 1-Segment Lumbar Disease. Clinical spine surgery. 2017 2017;30(6):E713-E719. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000334

9. Tumialán LM. Commentary: A Comparison of Minimally Invasive and Open Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion for Grade 1 Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis: An Analysis of the Prospective Quality Outcomes Database. Neurosurgery. 2020 2020;87(3):E306-E307. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyaa132

10. Halalmeh DR, Perez-Cruet MJ. Use of Local Morselized Bone Autograft in Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion: Cost Analysis. World neurosurgery. 2020/10/28 2020; 146:e544-e554. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.10.126

11. Yavin D, Casha S, Wiebe S, et al. Lumbar Fusion for Degenerative Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosurgery. 2017 2017;80(5):701-715. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyw162

12. Reid PC, Morr S, Kaiser MG. State of the union: a review of lumbar fusion indications and techniques for degenerative spine disease. Journal of neurosurgery Spine. 2019/07/01 2019;31(1):1-14. doi:10.3171/2019.4.SPINE18915

13. Mobbs RJ, Phan K, Malham G, Seex K, Rao PJ. Lumbar interbody fusion: techniques, indications and comparison of interbody fusion options including PLIF, TLIF, MI-TLIF, OLIF/ATP, LLIF and ALIF. Journal of Spine Surgery. 2015/12 2015;1 (1):2-18. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2414-469X.2015.10.05

14. Djurasovic M, Rouben DP, Glassman SD, Casnellie M, Carreon LY. Clinical Outcomes of Minimally Invasive versus Open Single Level TLIF: A Propensity Matched Cohort Study. The Spine Journal. 2014/10/21 2014;14(11):S28. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2014.08.076

15. Hammad A, Wirries A, Ardeshiri A, Nikiforov O, Geiger F, Wirries A. Open versus minimally invasive TLIF: literature review and meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2019 2019;14(1):1-21. doi:10.1186/s13018-019-1266-y

16. Qin R, Wu T, Liu H, Zhou B, Zhou P, Zhang X. Minimally invasive versus traditional open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of low-grade degenerative spondylolisthesis: a retrospective study. Scientific Reports. 2020 2020;10(1):1-10. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-78984-x

17. Goldstein CL, Macwan K, Sundararajan K, Rampersaud YR. Perioperative outcomes and adverse events of minimally invasive versus open posterior lumbar fusion: meta-analysis and systematic review. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2015/ 11/13 2015;24(3):416-427. doi:10.3171/2015.2.SPINE14973

18. Chen Y-C, Zhang L, Li E-N, et al. An updated meta-analysis of clinical outcomes comparing minimally invasive with open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in patients with degenerative lumbar diseases. Medicine. 2019 2019;98(43): e17420. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000017420

19. Hockley A, Ge D, Vasquez-Montes D, et al. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion Surgery: An Analysis of Opioids, Nonopioid Analgesics, and Perioperative Characteristics. Global Spine Journal. 2019/02/26 2019;9(6):624-629. doi:10.1177/2192568218822320

20. Anderson JT, Haas AR, Percy R, Woods ST, Ahn UM, Ahn NU. Chronic Opioid Therapy After Lumbar Fusion Surgery for Degenerative Disc Disease in a Workers’ Compensation Setting. Spine. 2015 2015;40(22):1775-1784. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000001054

21. Le H, Anderson R, Phan E, et al. Clinical and Radiographic Comparison Between Open Versus Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion With Bilateral Facetectomies. Global Spine Journal. 2020/06/22 2020;11(6):903-910. doi:10.1177/2192568220932879

22. Ge DH, Stekas ND, Varlotta CG, et al. Comparative Analysis of Two Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion Techniques: Open TLIF Versus Wiltse MIS TLIF. Spine. 2019 2019;44(9):E555-E560. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000002903

23. Ozgur BM, Yoo K, Rodriguez G, Taylor WR. Minimally-invasive technique for transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF). European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2005/09/08 2005;14(9):887-894. doi:10.1007/s00586-005-0941-3

24. Macki M, Hamilton T, Haddad YW, Chang V. Expandable Cage Technology—Transforaminal, Anterior, and Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Operative Neurosurgery. 2021 2021;21 (Supplement_1):S69-S80. doi:10.1093/ons/opaa342

25. Ambati DV, Wright EK, Lehman RA, Kang DG, Wagner SC, Dmitriev AE. Bilateral pedicle screw fixation provides superior biomechanical stability in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a finite element study. The Spine Journal. 2014/06/28 2014; 15(8):1812-1822. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2014.06.015

26. Administration USFaD. Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) Responsibilities Accessed November 5, 2024, https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/investigational-device-exemption-ide/ide-responsibilities

27. Huang Y-q, Gou R, Diao Y-s, et al. Charlson comorbidity index helps predict the risk of mortality for patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy*. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B. 2014/01 2014;15(1):58-66. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1300109

28. Jensen MP, Chen C, Brugger AM. Interpretation of visual analog scale ratings and change scores: a reanalysis of two clinical trials of postoperative pain. Journal of Pain. 2003 2003; 4(7):407-414. doi:10.1016/S1526-5900(03)00716-8

29. van Hooff ML, Mannion AF, Staub LP, Ostelo RWJG, Fairbank JCT. Determination of the Oswestry Disability Index score equivalent to a “satisfactory symptom state” in patients undergoing surgery for degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine-a Spine Tango registry-based study. The Spine Journal. 2016/06/22 2016;16(10):1221-1230. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2016.06.010

30. Abdallah DY, Jadaan MM, McCabe JP. Body mass index and risk of surgical site infection following spine surgery: a meta-analysis. European Spine Journal. 2013/07/05 2013;22(12):2800-2809. doi:10.1007/s00586-013-2890-6

31. A Concurrently Controlled Study of the LimiFlex™ Paraspinous Tension Band in the Treatment of Lumbar Degenerative Spondylolisthesis with Spinal Stenosis. Library of Medicine (US)

32. Wood MJ, McMillen J. The surgical learning curve and accuracy of minimally invasive lumbar pedicle screw placement using CT based computer-assisted navigation plus continuous electromyography monitoring – a retrospective review of 627 screws in 150 patients. International Journal of Spine Surgery. 2014 2014;8doi:10.14444/1027

33. Barbagallo GMV, Certo F, Visocchi M, Sciacca G, Piccini M, Albanese V. Multilevel mini-open TLIFs and percutaneous pedicle screw fixation: description of a simple technical nuance used to increase intraoperative safety and improve workflow. Tips and tricks and review of the literature. Neurosurgical Review. 2014/11/14 2014;38(2):343-354. doi:10.1007/s10143-014-0589-8

34. Virk S, Vaishnav AS, Sheha E, et al. Combining Expandable Interbody Cage Technology With a Minimally Invasive Technique to Harvest Iliac Crest Autograft Bone to Optimize Fusion Outcomes in Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion Surgery. Clinical spine surgery. 2021 2021; 34(9):E522-E530. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000001228

35. Kim CW, Doerr TM, Luna IY, et al. Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion Using Expandable Technology: A Clinical and Radiographic Analysis of 50 Patients. World Neurosurgery. 2016/02/24 2016;90:228-235. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2016.02.075

36. Alimi M, Shin B, Macielak M, et al. Expandable Polyaryl-Ether-Ether-Ketone Spacers for Interbody Distraction in the Lumbar Spine. Global Spine Journal. 2015/06 2015;5(3):169-178. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1552988

37. Wang MY. Improvement of sagittal balance and lumbar lordosis following less invasive adult spinal deformity surgery with expandable cages and percutaneous instrumentation. Journal of neurosurgery Spine. 2012/10/26 2012;18(1):4-12. doi:10.3171/2012.9.SPINE111081

38. Canseco JA, Karamian BA, DiMaria SL, et al. Static Versus Expandable Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK) Interbody Cages: A Comparison of One-Year Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes for One-Level Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion. World Neurosurgery. 2021/06/16 2021;152:e492-e501. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2021.05.128

39. Yee TJ, Joseph JR, Terman SW, Park P. Expandable vs Static Cages in Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion: Radiographic Comparison of Segmental and Lumbar Sagittal Angles. Neurosurgery. 2017 2017;81(1):69-74. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyw177

40. Chang C-C, Chou D, Pennicooke B, et al. Long-term radiographic outcomes of expandable versus static cages in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Journal of neurosurgery Spine. 2020/11/13 2020;34(3):471-480. doi:10.3171/2020.6.SPINE191378

41. Rymarczuk GN, Harrop JS, Hilis A, Hartl R. Should Expandable TLIF Cages be Used Routinely to Increase Lordosis? Clinical spine surgery. 2017 2017; 30(2):47-49. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000510