Burkitt Lymphoma: Insights on Chemotherapy Outcomes

Burkitt Lymphoma A Model of Cancer Chemotherapy

Christopher K. Williams, MD, FRCPC1

- Department of Hematology, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria; Department of Hematology, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria; Department of Medical Oncology, Allan Blair Cancer Center, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; Saskatchewan Cancer Foundation, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada; Department of Medical Oncology, British Columbia Cancer Agency, Vancouver, BC, Canada; Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 28 Febuary 2025

CITATION: WILLIAMS, Christopher K.. Burkitt Lymphoma – A Model of Cancer Chemotherapy. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 2, feb. 2025. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6109>. Date accessed: 25 oct. 2025. doi: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i2.6109.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i2.6109

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Purpose: This report seeks to validate some of the findings in animal models of cancer chemotherapy with observations in the real-world management of endemic Burkitt lymphoma in Nigerian children between 1979 and 1986.

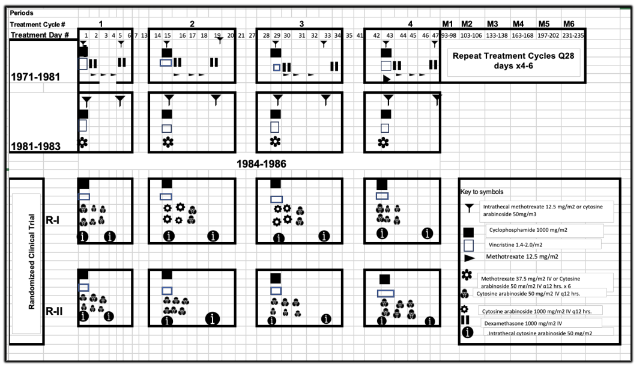

Materials and Methods: Between 1979 and 1981, a period of relative affluence in Nigeria, children with Burkitt lymphoma were treated with an induction course of four 14-day cycles of combination regimens: vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 on day 1, cyclophosphamide 1000 mg/m2 on day 1, methotrexate 12.5 mg/m2 on day 2, 3 and 4, and intrathecal treatment with methotrexate 12.5/m2 or cytosine arabinoside 50mg/m2 on day 1 and day 5 of 4 cycles, followed by 4-6 28-day cycles as maintenance. By 1981-1983, socioeconomic challenges led to loss of treatment quality, including variability in dose intensity and duration. Between 1984 and 1986, the children were managed on a randomized phase II clinical trial, in which donated cytosine arabinoside at high doses, e.g., 1000mg/m2 IV q12 hours x 4 doses was given, with the aim of overcoming physiological barrier for better control of central nervous system involvement.

Results: Chi-square test showed strong correlation between remission rate and dose intensity of single agents and mean relative dose intensity of combination chemotherapy (p< 0.0001), while Cox proportion hazard model revealed association between progression free survival and mean relative dose intensity (p = 0.0001) regardless of central nervous system involvement (p = 0.0003). Evaluation by log-rank test revealed highly significant association between less than 42, and more than 43 to 95 treatment days and progression free survival (p<0.0001), but, counterintuitively, not with more than 95 days (p=0.809). The clinical trial regimens led to complete plus partial response rates of 100% vs 45% and progression free survival rate of 64% vs 19.7% (p=0.205), and mean relative dose intensities of 592.2 vs 102.6 (p<0.0001) in the experimental and control arms, respectively.

Conclusion: The clinical manifestations of the disease as well as the treatment outcomes in correlation with treatment qualities reflect predictable observations in animal models, thus, confirming the relevance of adherence to the principles of chemotherapy in clinical practice.

Keywords

Burkitt lymphoma, chemotherapy, dose intensity, treatment outcomes, pediatric oncology

INTRODUCTION

The discovery in 1956 of a unique cancer of African children, later to be named Burkitt lymphoma (BL) after its discoverer, Denis Burkitt, led to a new understanding of cancer, which had hitherto been an enigma. It proved to be a watershed moment that Gaius Plinius Secundus, also known as Pliny the Elder, seemed to have presaged in his quote: “There is always something new out of Africa.” The quote by itself implies that Africa is a place where unique and fascinating discoveries are constantly being made. These discoveries could span a wide range of fields, including but not limited to natural history, culture, and scientific advancement. The discovery of BL led to a new knowledge of human cancer, including its association with environment factors as well as its curability by chemical agents. This, in turn, was to lead to the emergence of theoretical models and the use of chemotherapeutic agents in addressing the emerging insight of the natural phenomena of cancer. Cyclophosphamide, one of the alkylating agents to emerge from World War II warfare industry, was the first agent to be recognized for the cure of BL and has remained the backbone of the BL armamentarium.

Theoretical models of cancer chemotherapy have subsequently established a role for combination of agents, which have emerged progressively in the 1960s and 1970s. Investigators at the US-Uganda Cancer Institute in Kampala developed several treatment regimens for the management of BL, including one containing a three-drug combination consisting of cyclophosphamide, vincristine and methotrexate, modifications of which remain the mainstay in the management of BL, resulting in about 50% to 80% cure rates of the disease. Furthermore, the discoveries of the characteristic properties of BL, including its cell kinetics, molecular biology and immunology, are indicating routes to early diagnosis and other therapeutic interventions for management advances in BL. Some of these advancements were pioneered by investigators at the University College Hospital (UCH) of the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. The work, which is being reported herein, is based on a seven-year experience of the management of Nigerian children beginning in 1979 -1981 with the 3-drug treatment regimen that had been developed at the US-Uganda Cancer Institute. In the succeeding 2 years (1981-1983), however, prevailing socioeconomic situation in Nigeria had necessitated significant changes in the administration of the regimen, thereby leading to variability in the quality of treatment in terms of doses of the individual drugs as well as the treatment durations. Observations of the patterns of treatment failures in the earlier 5 years of this work indicated a need for central nervous system directed strategies to reduce the risk of disease recurrence in the region. This was made possible in the period of 1984-1986 through the availability of a large amount of donated cytosine arabinoside, a drug that overcomes the blood-brain barrier at high doses. The availability of the drug was a stimulus for the management of BL children on a randomized clinical trial. This was preceded by an informal trial of intravenous ARA-C given at high doses, e.g., 1000 mg/m2 to 3 children with CNS involvement by BL. The trial revealed accepted degree of tolerance as well as remarkable efficacy in form of rapid clearance of CNS fluid pleocytosis (C.K. Williams, unpublished observation), thus, indicating its potential as a treatment strategy in the locality, thus, leading to a randomized phase II trial of high dose cytosine arabinoside based regimen in BL. The outcomes observed in the management of these children have been combined and analyzed in order to observe how their presentation features, the treatment quality and the resulting outcomes could be applied to validate principles of cancer chemotherapy.

The unique story of Burkitt lymphoma and its impact on historic cancer narratives as well the use of data derived from its clinical management to validate hypotheses of chemotherapeutic principles generated in animal models should be attractive to healthcare workers, medical scientists, historians, biologists, anthropologists and even philosophers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PATHOLOGIC DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of BL was based on clinical, cytological/histological and radiological features. These included presentation with typical jaw masses with radiological evidence of dental anarchy, and effacement of the lamina dura. Other classical clinical features included the presence of massive abdominal and or pelvic (ovarian) masses. Diagnostic pathological features included the observation of the classical “starry sky appearance” of a hematoxylin-eosin-stained paraffin section, or the presence of cytoplasmic vacuolation of the lymphoid cytoplasm. Other diagnostic methods used included bone marrow examination, lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid examination, urography and ultrasonography of abdominal and pelvic structures. Routine hematologic and blood chemistry (including SGOT, SGPT, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, uric acid) was obtained as part of initial assessment of the patients. Estimation of blood lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) was not available. Using indirect immunofluorescence technique and monoclonal antibodies, lymphoblasts derived from tumor sources in a number of the patients were immunophenotyped, and studied for gene rearrangement studies to further characterize the lymphoblasts.

STAGING

The patients were assigned to one of four stages: stage A: single extra-abdominal mass; stage B: multiple extra-abdominal masses; stage C: abdominal mass with or without facial tumor; stage D: abdominal mass with sites of tumor other than facial. The classification was modified by characterizing selective bone marrow involvement as Dsystemic, while cases with central nervous system involvement were characterized as Dcns. Cases, in which the bone marrow and the central nervous system were involved, with or without involvement of other organs were characterized as Dsystemic+cns.

TREATMENT

The first series of patients were treated (Figure 1) between 1979 and 1981 with a modified form of a regimen described by Ziegler and consisted of cyclophosphamide 1000mg/m2 iv on day 1, vincristine 1.5mg/m2 iv on day 1, methotrexate 12.5mg/m2 iv on days 1, 3, and 4, dexamethasone 1000mg/m2 iv on days 2 and 5. These medications were delivered at 14-day intervals for a total of 4 cycles as an induction course. Thereafter 3-6 more cycles were given at monthly intervals as a maintenance course. Subsequent to frequent occurrence of shortage of drugs, the treatment regimen was modified in 1981-1983 by combining the three methotrexate doses to a single dose of 37.5mg/m2 iv on day 1 or orally in 3 divided daily doses, or replaced by iv cytosine arabinoside 50mg/mg2 in six 12-hourly doses (each dose being given as a 3-hour infusion). Intrathecal treatment was either by methotrexate 12.5/m2 or cytosine arabinoside 50mg/m2 on days 1 and 5 of each of the four 14-day cycles. Patients seen between 1984 and 1986 (Figure 1) were randomized on a study of the efficacy of high dose of cytosine arabinoside as compared to the standard dose. Patients randomized to the high dose arm received the drug at the dose of 1000mg/m2 12-hourly for four of 6 doses in the 2 middle cycles of four 14-day treatment cycles. The remaining 2 of the 6 doses of each of these two cycles, the first and the fourth cycles of the high-dose regimen arm as well as each of the four cycles of the standard-dose regimen arm were delivered as previously described.

MANAGEMENT OF BURKITT LYMPHOMA

TREATMENT DOSE INTENSITY

The calculation of received dose intensity and received mean relative dose intensity was based on the methods of Hryniuk. In the calculation, the assumption was made that the schedule and the route of drug delivery were of less importance than the dose intensity. The dose of steroids was ignored in the calculation of mean RDI on the assumption that these agents have little impact on treatment outcome in Burkitt’s lymphoma. The “standard regimens” used in calculation of mean RDI was that of Nkrumah for cytosine arabinoside containing regimens, and that of Ziegler for methotrexate containing regimens.

COMPLIANCE AND SUPPORTIVE CARE

In order to ensure maximal compliance, patients were encouraged to remain in the hospital for the entire period of induction chemotherapy (i.e., for 5 to 6 weeks).

UNIQUE OPERATIONAL CHALLENGES

Beginning in 1982 following the collapse of the international price of petroleum, the mainstay of Nigeria’s economy, the supply of chemotherapeutic agents became increasing erratic. Parents had to purchase some of the drugs, especially vincristine, for their wards, or none was given to the children. Strikes and other industrial actions became rampant thereby leading to interrupted and delayed treatments. The level of compliance of the parents varied and treatment was frequently interrupted and the children were often prematurely removed from the hospital. Since many of the children came from remote villages, in some cases up to several hundreds of kilometers away, while others resided in nameless and unreachable areas of the metropolis of Ibadan, the process of follow-up was difficult and unsatisfactory. Consent for investigations and treatments could only be obtained by mutual oral agreement between the investigators and the parents of the patients.

ASSESSMENT OF TREATMENT OUTCOMES

Treatment outcomes evaluated include remission status, remission duration, and progression free survival. The remission date is defined as the last day of remission induction chemotherapy in a patient achieving complete or partial remission. Relapse or progression date is defined as the date that either systemic or CNS disease is documented either physically, radiological or cytologically.

STATISTICAL METHODS

Chi-square analysis was performed to test the association between dose intensity and remission rate. Survival curves were estimated according to Kaplan-Meier life-table method and differences between curves were compared using the generalized Wilcoxon test. Cox multivariate models were performed to assess the prognostic factors by SAS LIFETEST procedure. The level of significance was set at 0.05. All p-values in this paper correspond to two-sided significance tests. SAS statistical software was used for these analyses.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the 113 previously untreated Burkitt lymphoma patients seen at the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria between 1979 and 1986, and their demographic characteristics are provided in shown in Table 1. There was a ratio 21:16 preponderance of boys, with the median age being 8.5 years (95% confidence interval [C.I.]: 7.82-9.07).

TUMOR SIZE DEFINING LOW BULK AND HIGH BULK

The mean size of the largest tumors was 11.4 cm in maximum dimension (C.I.: 9.8-12.9). Most of the largest tumors (41 of 79: 52%) measured between 0 and 10 cm in maximum dimension, while in 21 (26.6%) and 17 (21.5%) of other tumors, the maximum dimension was 11-15 and 16 cm, respectively. Defining a cutoff point below 10 cm was a challenge. This is in spite of the use of the conventional cutoff level of 10 cm. Other cutoff levels of 5 cm, 8 cm, 15 cm and 20 cm were of no value for statistical test (chi-square test) in the correlation of tumor size and disease outcomes.

| Means | 95% C.I. |

|---|---|

| Age | 8.5 |

| Subcategories | # Cases Total |

| 2.3-25.0 Tumor Size in cm | |

| <=5 | 23 |

| >5 | 64 |

| <=8 | 34 |

| >8 | 53 |

| <=10 | 46 |

| >10 | 41 |

| <=12 | 54 |

| >12 | 33 |

| <=15 | 69 |

| >15 | 18 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 63 |

| Female | 48 |

| Unknown | 2 |

| Stage | |

| A+AR+B | 10 |

| C+Dsystemic | 52 |

| Dcns | 51 |

STAGE

Most patients (92 of 101: 92%) presented with advanced disease, either with central nervous system (CNS) involvement (Stage Dcns) or without CNS involvement (Stages C or Dsystemic).

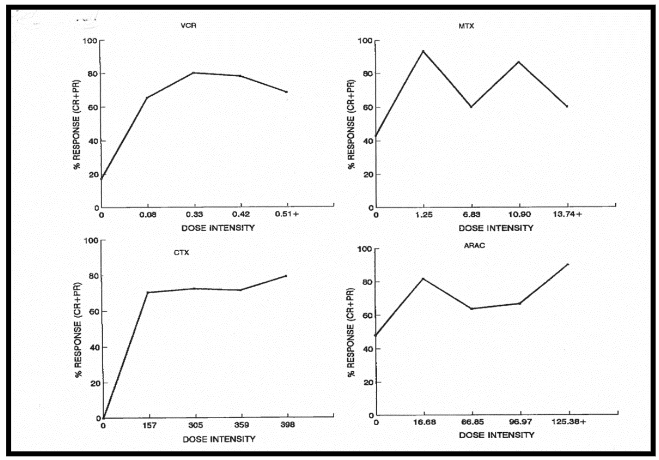

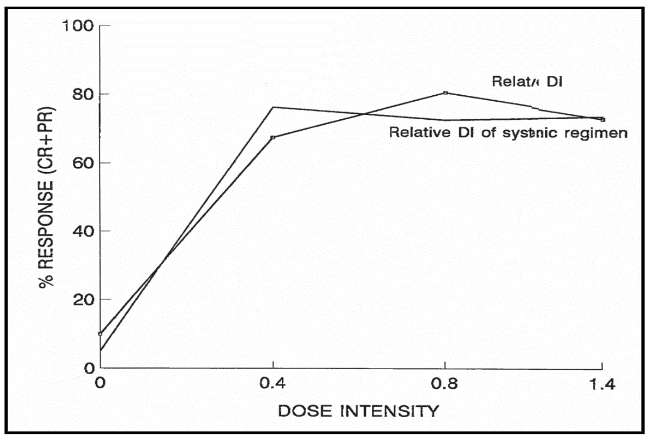

TOTAL DOSE, DOSE INTENSITY AND RELATIVE DOSE INTENSITY

The threshold dose intensities (per m2/week) estimated for vincristine (VCR), methotrexate (MTX), cyclophosphamide (CTX), and cytosine arabinoside (ARA-C) are 0.1mg, 1.0mg, 160mg and 17mg respectively. The relationship between treatment outcome and mean relative dose intensity is highly significant at the level of p<0.0001, whether the calculation of the latter pertains to systemically administered agents only, or it is based on the combination of systemically and intrathecally administered agents.

| Prognostic factors | p-values |

|---|---|

| Total dose of cyclophosphamide | 0.0009 |

| Dose intensity of intrathecal methotrexate | 0.04 |

| Gender | 0.06 |

| Total dose of methotrexate | 0.06 |

| Total dose of cytosine arabinoside | 0.09 |

| Stage | 0.11 |

ESTIMATING TUMOR BURDEN

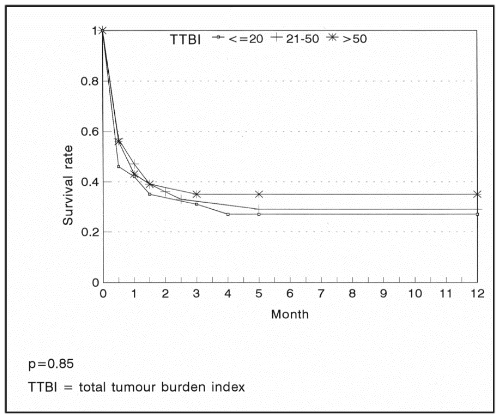

Consequent upon the lack of laboratory facilities for determining serum LDH levels, which correlates well with tumor volumes, and in order to define the criterion of low and high tumor burden, we established the concept of total tumor burden index (TTBI). This was arbitrarily defined as the product of a number assigned incrementally to the stage and the maximum diameter measurable on any tumor.

TUMOR SIZE, TUMOR BURDEN INDEX AND TREATMENT OUTCOME

We found no statistically significant difference in remission or survival rates observed in the three categories of tumor burden index (TTBI) examined, namely <=20, 21-50, and >50 (p=0.83).

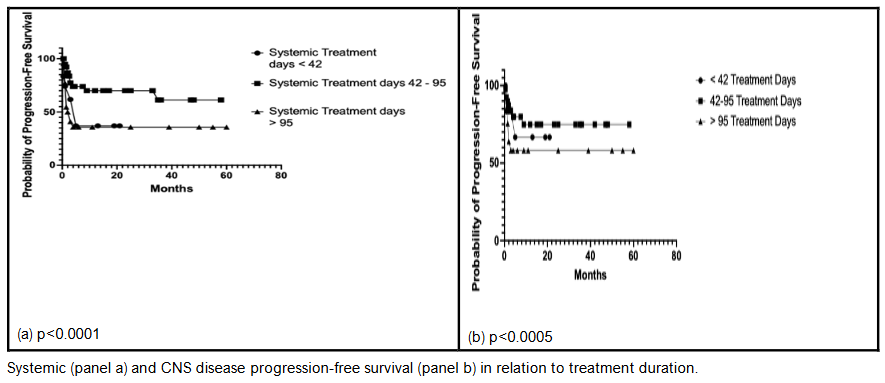

TREATMENT DURATION AND SURVIVAL

The relationship between treatment duration and survival is shown in Figure 5. The survival rate was better among patients treated for 43-94 days than those treated for 42 days or less (p=0.0001). Multivariate Cox model analysis showed other factors associated with optimal survival, as shown in Table 2, to include dose intensity of intrathecal medication, gender (females did better than males), relative dose intensity of systemic and intrathecal treatments, disease stage, total dose of intrathecal medication and the dose intensity of cyclophosphamide.

| * | Three categories of RDI |

|---|---|

| <0.4 | 5-6 10-11 |

| <0.4-0.6 | 50 37 75 |

| >0.6 | 50 37 75 |

DOSE INTENSITY OF SINGLE AGENTS AND RELATIVE DOSE INTENSITY OF DRUG COMBINATIONS

Using Cox proportional hazard model, no statistically significant relationship was observed between progression free survival and the dose intensities of the individual agents of VCR, MTX, CTX, and ARA-C. However, the association between progression free survival with relative dose intensity of combination chemotherapy was highly significant at p=0.0001.

| Factor | p-value |

|---|---|

| High-bulk disease | |

| Treatment days (<= 42) | <0.0001 |

| Low-bulk disease | |

| Treatment days (<= 42) | <0.0001 |

We found no statistically significant correlation between treatment outcome and disease bulk. However, treatment outcome correlated with the relative dose intensity of treatment; i.e., the higher the relative dose intensity of treatment, the better the treatment outcome, regardless of the tumor bulk. We found no statistically significant relationship between total tumor burden index and outcome as determined either by remission rates or overall survival.

In high-bulk disease (tumor size >= 10cm) treatment outcome was 3 times better in cases who received systemic chemotherapy for 43-95 days (76% complete/partial remission) compared with cases treated for <= 42 days (20% complete/partial remission). This difference is statistically highly significant at p<0.0001. In low bulk disease, a similar situation was observed with the patients treated for 43-95 days showing a significantly better outcome (87% complete/partial remission) compared to cases with treatment duration of <=42 days (8% complete/partial remission) (p<0.0001). As shown in figure 4, regardless of tumor-size category, there is a correlation between progression free survival and treatment duration both in relation to systemic and central nervous system disease.

Figure 5: Systemic disease progression-free survival

Systemic disease progression-free survival

DISCUSSION

The past 50 years have witnessed a frenetic evolution of cancer medicine, emerging from historical global cluelessness about the disease and propelled by the massive investments that followed the enactment of the National Cancer Act of the United States in 1971. This has resulted in the systemic therapy of cancer, consisting in the conventional chemotherapy, hormonal, and targeted therapy as well as immunotherapy, which together, are responsible for the improvement in cancer related mortality in developed countries even as the population continues to age. In the developing world, where the majority of humanity resides, the most accessible systemic therapy is the conventional chemotherapy, hence the relevance of elucidating its background.

Models for cancer chemotherapy effects were initially developed based on data from experimental chemotherapy models and have subsequently been confirmed by outcomes in clinical practice. Thus, the superiority of treatment regimens with higher doses, and higher dose intensities has been shown in retrospective analysis of chemotherapy of advanced lymphoma as well as in prospective studies of chemotherapy of childhood lymphoblastic leukemia, adult germ cell tumor and advanced breast cancer. The results reported in this paper, even though they emanated largely from real-world practice rather than experimental designs, further confirm the validity of the association between treatment dose intensity and treatment outcomes as demonstrated by the strong correlation observed between remission rates and the dose intensities of single agents and the mean relative dose intensity of combination regimens, as well as between progression free survival and mean relative dose intensity. A similar association was observed between total dose of received single agents and remission rate. The data were generated more than 35 years ago and are probably the oldest of such data anywhere, and have previously been presented at a symposium of the American Association for Cancer Research in 1996.

The estimated threshold dose of vincristine in the combination regimens used in this study is, at 0.08mg/m2/week, only 16% of the threshold dose of 0.5mg/m2/week of the drug for breast cancer. Thus, Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is at least 6 times more sensitive than breast cancer to vincristine. A similar situation probably exists in terms of the sensitivity of Burkitt lymphoma to other antineoplastic agents. These observations suggest that BL may serve better as a human model of cancer chemotherapy than breast cancer and, probably, other human cancers.

The limitations of the Goldie-Coldman’s hypothesis in cancer biology has been extensively discussed. Particularly notable is its failure to explain the dramatic results obtained in some drug-sensitive neoplasia such as BL and choriocarcinoma. Given the enormous sizes at presentation of many cases of BL, it is amazing that the disease is so curable at a considerable rate by chemotherapy. The failure in this study to observe an inferior treatment outcome in association with large compared to smaller BL would tend to indicate the invalidity of this hypothesis in practical oncology. It would seem that BL masses consist of cells that are probably heterogenous in term of drug sensitivity. However, in view of the generally increased drug sensitivity, the relative sensitivity of a good proportion of the tumor is well within the pharmacologically achievable range.

PROGRESSION FREE SURVIVAL AND TREATMENT DURATION

The results of our study also underline the importance of treatment duration, among other treatment and disease factors, in the overall treatment outcome. Other treatment regimens reporting better treatment outcomes have been delivered over a much longer periods of times, including the treatment regimens of Murphy et al. While the longer duration of treatment may not be the only reason for their successful outcome of these treatment regimens, it probably played a significant role. The findings in our study suggest that treatment duration may be relatively more important than other recognized determinants of treatment outcome in BL, including stage, bulk and the type of chemotherapeutic agent. On the other hand, it would seem that treatment duration in BL is unlikely to be open ended and indefinite, based on the observation in this study, though unexpected and rather counter intuitive, that treatment duration of 95 days or longer is not better than treatment for 42 or less and worse than that of 43-95 days.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TUMOR BURDEN AND CURABILITY OF CANCER

Observations in experimental models indicate that as tumor population increases over time, there is an increasing likelihood that one drug-resistant clone will spontaneously appear in the tumor, and that with more growth in the tumor population, and the longer the elapsed time is from tumor initiation and its management with chemotherapy, the greater the likelihood of emergence of chemotherapy resistance clones. In other words, the longer the delay of diagnosis, the higher the tumor bulk, the greater the likelihood of emergence of drug-resistant mutants, the lower the likelihood of successful chemotherapeutic effectiveness. The probability of cure is related to both tumor size and the mutation rate to resistance. The lower the latter quality is, the greater the probability of cure for any tumor size. In other words, the higher the growth rate, the higher the mutation rate to treatment resistance. Given the fact that BL has the highest mutation rate in human oncogenesis, and with 92% of the Nigerian BL patients presenting with advanced disease, the relatively poor outcome on standard treatment regimen is to be expected based on the natural dynamics of malignancy.

The adverse features of advanced tumor burden on reduced curability of BL can be extrapolated to observation in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Ibadan, Nigeria. Using a treatment regimen that was not significantly dissimilar to a standard treatment used in developed countries in the early 1980s, treatment outcomes in Nigerian patients were inferior to the contemporary outcomes in developed countries. This was not only so in Nigeria, but also in India. The causes of delayed treatment for cancer in a developing country like Nigeria are numerous, and include lack of awareness by the patients and their caregivers, lack of diagnostic capabilities and failure of healthcare infrastructure leading to inability to access diagnostic evaluation in timely manner. The effort to reduce diagnostic delay is the subject of current research endeavor, with the aim of reducing the time to diagnosis by screening of at-risk populations with flow cytometry and genetic testing for early detection of genetic markers of BL, in susceptible population. As health care challenges in the developing world transition from communicable to non-communicable diseases, and as has previously been recognized in international fora, such as the UNGAS 2012, the key to progress in the management of cancer and other noncommunicable diseases in the developing world is early disease recognition.

OVERCOMING RESISTANCE IN BURKITT LYMPHOMA CHEMOTHERAPY

The same mathematical function that defines curability with respect to tumor size can also be used to develop a rationale for combination chemotherapy. The probability of cure is related to both tumor size and the mutation rate to resistance. Thus, various strategies have been proposed as ways and means of overcoming drug resistance. One such proposals involved augmentation of treatment dose, while another involves the use of fixed alternation schedules using equivalent non-cross resistant drug combinations, e.g., the MOPP/ABV regimen for the treatment of advanced Hodgkin lymphoma.

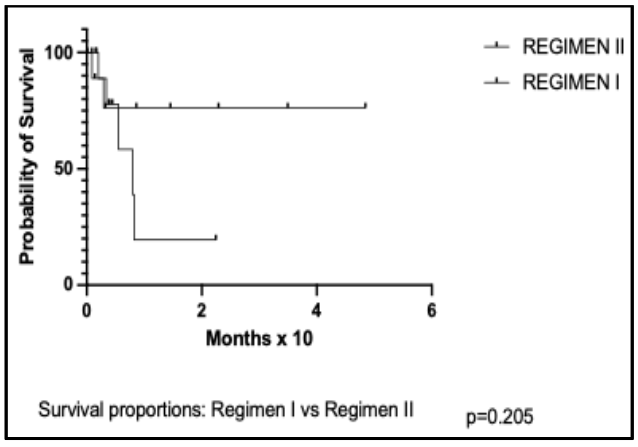

Figure 6: Clinical trial of the effectiveness of high-dose cytosine arabinoside in Burkitt lymphoma.

strategies have been proposed as ways and means of overcoming drug resistance. One such proposals involved augmentation of treatment dose, while another involves the use of fixed alternation schedules using equivalent non-cross resistant drug combinations, e.g., the MOPP/ABV regimen for the treatment of advanced Hodgkin lymphom

| Demography | R-I | R-II | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomized | 14 (20-30)* | 16 (20-30)* | ||

| Male/Female | 4/10 | 6/10 | >0.5 | |

| Stages | ||||

| C | 5 | 6 | ||

| D-CNS+ | 4 | 6 | ||

| D-CNS- | 4 | 3 | ||

| Undetermined | 1 | 1 | ||

| DI of agents | ||||

| Vincristine | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.2 | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 304 | 353 | 0.54 | |

| Intravenous cytosine arabinoside | 592.2 | 102.6 | <0.0001 | |

| Intrathecal cytosine arabinoside | 26.6 | 33.7 | 0.39 | |

| Outcomes | Number evaluated | 9 | 11 | |

| Complete remission (%) | 9/9 (100) | 6/11 (54.5) | ||

| Partial remission (%) | 0/9 (0.0) | 4/11 (36.4) | ||

| No remission (%) | 0/9 (0.0) | 1/11 (9.2) | ||

| Survival proportion (%) | 64.2 | 19.7 | 0.205 |

The BL treatment experience at the UCH, Ibadan, Nigeria between 1979 and 1986 are outlined in Figure 1. While the observations in 1979 1981, and 1981 to 1983 have been used to evaluate the importance of treatment duration, those of 1984 to 1986 enabled us to evaluate the role of treatment dose intensity, and, probably, the effectiveness of the use of alternating schedules of non-cross resistant drug combinations. In the randomized clinical trial of 1984 to 1986, Regimen II is comparable in design and efficacy to what obtained in standard practice. The main difference between Regimen I and Regimen II is the use of high-dose cytosine arabinoside in cycles 2 and 3 of Regimen I, alternating with standard treatment in cycles 1 and 4. Thus, the marked difference observed in survival in Regimen I patients is attributable to the DI of cytosine arabinoside, and, possibly, also its use in form of alternation schedule as a non-cross resistant drug combination. Although the survival difference between the two regimens is statistically insignificant, this is because the study was not designed or executed to demonstrate a survival difference, but rather to show efficacy and safety. As has been indicated earlier, the design of the regimens used at the various timelines of the work that have led to this report were done in response to various extraneous factors. Thus, the use of high doses of cytosine arabinoside only in the second and third of the four treatment cycles was, primarily, to reduce the risk of tumor lysis in the exposure of bulky disease to intensive treatment in cycle 1, thereby reducing the need for unavailable supportive care. Furthermore, not giving the drug in a high dose in the fourth cycle was because of the limited availability of the drug in our coffers. It is apparent that the outcomes with this pattern of the use of the drug is also consistent with the effectiveness of alternating non-cross resistant regimens.

CONCLUSION

Several biological features of Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) have provided insight into human oncogenesis. Given its unique biological features, including its high proliferative state, BL provides a unique opportunity as a model in understanding cancer management with chemotherapeutic agents. The more recent emergence of newer forms of systemic cancer therapies described earlier neither invalidate the principles of cancer chemotherapy nor render them obsolete. While they operate on different principles, they are increasingly being used in complementary fashion, e.g., as antibody drug conjugates, where monoclonal antibodies are used for greater delivery of traditional cytotoxic drugs for targeting cancer cells. In other situations, emerging knowledge of some cancer types are indicating a need for combined use of classes of systemic cancer therapy agents. An example of this is the use of the immune checkpoint agent nivolumab in the management of classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

Even though preliminary reports of this work were published more than 25 years ago, the disruptive impact of socioeconomic readjustment of the succeeding era has made similar work in the region virtually untenable. The fact that the data were garnered from real-world practice in a developing country should encourage practitioners, especially those in the developing world, in recognizing the need to keep to the principles of the use of chemotherapeutic agents for desirable outcomes. The failure to adhere consistently to chemotherapeutic principles is the basis of management failures as reported from a number of Nigerian institutions, where complete response rates of 35% and one-year overall survival of less than 5%, compared to 44%, 81% and 61%, respectively, have been reported. Other factors that would limit adequate BL management, such as reduced treatment duration for less than 43, must be avoided with determination. Furthermore, the data on late diagnosis and its association with poor treatment outcomes should encourage health care policy makers to recognize the need for early cancer diagnosis and avoidance of disease recognition at stages, at which prospects for cure are reduced.

Conflict of Interest:

None.

Funding Statement:

1. Clinical and population studies at the University College Hospital were funded in part by grants of the National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA) of the Federal Government of Nigeria.

2. Dr. Ian Magrath, formerly of the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA, and of the International Cancer Network, Brussels, Belgium, facilitated the connection to Upjohn Company of Kalamazoo, MI, USA, who generously provided cytosine arabinoside free for the randomized study of 1984-1986.

3. Funding for the statistical analysis was provided with grants of the Saskatchewan Cancer Foundation.

Acknowledgements:

Statistical analysis was performed by Ms Liyan Liu, former Research Officer, Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada.

Ethics Committee approval:

Professor Olatunbosun, formerly of the Department of Chemical Pathology, and former Chairman of the Ethics Committee of the University College Hospital, was helpful in the approval of phase II study of high-dose cytosine arabinoside in the management of Burkitt lymphoma, 1984-1986.

References

1. Burkitt D. A sarcoma involving the jaws in African children. Br J Surgery. 1958;197:218-223.

2. Bekoz H, Ozbalak M, Karadurmus N, et al. Nivolumab for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: real-life experience. Annals of Hematology. 2020;99:2565-2576.

3. Gibson R, Morello R. Pliny the Elder: themes and contexts. vol 329. Brill; 2011.

4. Feinberg HM, Solodow JB. Out of Africa. The Journal of African History. 2002;43(2):255-261.

5. Soyinka W. Of Africa. Yale University Press; 2012.

6. Asante MK. The history of Africa: The quest for eternal harmony. Routledge; 2018.

7. The Socratic Method. https://www.socratic-method.com/quote-meanings/pliny-the-elder-there-is-always-something-new-out-of-africa#google_vignette

8. Magrath I. Epidemiology: clues to pathogenesis of Burkitt lymphoma. British Journal of Haematology. 2012;156(6):744-756.

9. Williams CK. African Environmental Pressures and Carcinogenesis: The Impact on The Lymphomas, the Leukemias, and Breast cancer. Medical Research Archives. 2024;12(2)

10. Schabel F, Skipper HE, Trader M, al e. Concept for controlling drug resistant tumor cells. In: HT M, T P, eds. Breast cancer – Experimental and clinical aspects. Pergamon Press; 1980:199-212.

11. Schabel F. Concepts for systemic treatment of micrometastases. Cancer. 1975;35(1):15-24.

12. Goldie J, Coldman A. A model for tumor response to chemotherapy: an integration of the stem cell and somatic mutation hypotheses. Cancer investigation. 1985;3(6):553-564.

13. Goldie J, Coldman A. Application of theoretical models to chemotherapy protocol design. Cancer Treat Rep. 1986;70(1):127-31.

14. Gustafson DL, Page RL. Cancer chemotherapy. Withrow and MacEwen’s small animal clinical oncology. 2013:157-179.

15. DeVita VT, Chu E. A history of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer research. 2008;68(21):8643 -8653. doi:DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6611

16. Ziegler JL, Morrow RH, Fass L, Kyalwazi SK, Carbone PP. Treatment of Burkitt’s tumour with cyclophosphamide. Cancer. 1970;26:474-484.

17. Ihonvbere JO. Economic crisis, structural adjustment and social crisis in Nigeria. World Development. 1993;21(1):141-153.

18. Ziegler J, Magrath I, Olweny CM. Cure of Burkitt’s lymphoma: Ten-year Follow-up of 157 Ugandan patients. The Lancet. 1979;314(8149): 936-938.

19. Murphy S, Bowman W, Abromowitch M, et al. Results of treatment of advanced-stage Burkitt’s lymphoma and B cell (SIg+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia with high-dose fractionated cyclophosphamide and coordinated high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1986;4(12):1732-1739.

20. Magrath I, Adde M, Shad A, et al. Adults and children with small non-cleaved-cell lymphoma have a similar excellent outcome when treated with the same chemotherapy regimen. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1996;14(3):925-934.

21. Iversen OH, Iversen U, Ziegler JL, Bluming AZ. Cell kinetics in Burkitt lymphoma. European Journal of Cancer (1965). 1974;10(3):155-163.

22. Della-Favera R, Bregni M, Erikson J, Patterson D, Gallo R, Croce C. Human c-myc oncogene is located on the region of chromosome 8 that is translocated in Burkitt’s lymphoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982:7824-7827.

23. Rossig C. CAR T cell immunotherapy in hematology and beyond. Clinical Immunology. 2018;186:54-58.

24. Langat S, Njuguna F, Mostert S, et al. A phase II trial testing interventions to shorten time to diagnosis and reduce abandonment of treatment of children with Burkitt lymphoma in Kenya. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2019.

25. Zayac AS, Olszewski AJ. Burkitt lymphoma: bridging the gap between advances in molecular biology and therapy. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2020;61(8):1784-1796.

26. Aldoss IT, Weisenburger DD, Kai Fu M, et al. Adult Burkitt lymphoma: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Oncology. 2008;22(13):1508.

27. Gastwirt JP, Roschewski M. Management of adults with Burkitt lymphoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2018;16(12)

28. Crombie J, LaCasce A. The treatment of Burkitt lymphoma in adults. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2021; 137(6):743-750.

29. Della Rocca AM, Leonart LP, Ferreira VL, et al. Chemotherapy treatments for Burkitt lymphoma: Systematic review of interventional studies. Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia. 2021;21(8): 514-525.

30. Evens AM, Danilov A, Jagadeesh D, et al. Burkitt lymphoma in the modern era: real-world outcomes and prognostication across 30 US cancer centers. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2021;137(3):374-386.

31. Dozzo M, Carobolante F, Donisi PM, et al. Burkitt lymphoma in adolescents and young adults: management challenges. Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics. 2016:11-29.

32. Ozuah NW, Lubega J, Allen CE, El-Mallawany NK. Five decades of low intensity and low survival: adapting intensified regimens to cure pediatric Burkitt lymphoma in Africa. Blood Advances. 2020;4(16):4007-4019.

33. López C, Burkhardt B, Chan JK, et al. Burkitt lymphoma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2022;8(1):78.

34. Hoelzer D, Walewski J, Döhner H, et al. Improved outcome of adult Burkitt lymphoma /leukemia with rituximab and chemotherapy: report of a large prospective multicenter trial. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2014;124(26):3870-3879.

35. Osunkoya BO. Trends of experimental cancer research in Nigeria. In: Solanke FT, Osunkoya BO, Williams CKO, Agboola OO, eds. Cancer in Nigeria. Ibadan University Press, Publishing House; 1982.

36. Tangwa GB. Giving voice to African thought in medical research ethics. Theoretical medicine and bioethics. 2017;38(2):101-110.

37. Tangwa GB. Giving Research Voice Ethics* to African Thought in Medical. Global Health: Ethical Challenges. 2021:339.

38. Williams CKO. Cancer and AIDS: Part I: An Historical Perspective. Springer; 2018.

39. Williams C, Folami A, Seriki O. Patterns of treatment failure in Burkitt’s lymphoma. European Journal of Cancer and Clinical Oncology. 1983; 19(6):741-746.

40. Slevin M, Piall E, Aherne G, Johnston A, Sweatman M, Lister T. The pharmacokinetics of subcutaneous cytosine arabinoside in patients with acute myelogenous leukaemia. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 1981;12(4):507-510.

41. Slevin M, Piall E, Aherne G, Johnston A, Lister T. The pharmacokinetics of cytosine arabinoside in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid during conventional and high‐dose therapy. Medical and pediatric oncology. 1982;10(S1):157-168.

42. Olweny CL, Katongole‐Mbidde E, Bahendeka S, Otim D, Mugerwa J, Kyalwazi SK. Further experience in treating patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Uganda. Cancer. 1980;46(12):2717-2722.

43. Greaves MF, Pegram SM, Chan L. Collaborative group study of the epidemiology of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia subtypes: background and first report. Leukemia Research. 1985;9(6):715.

44. Foroni L, Catovsky D, Rabbitts T, Luzzatto L. DNA rearrangements of immunoglobulin genes correlate with phenotypic markers in B-cell malignancies. Molecular biology & medicine. 1984;2(1):63.

45. Williams CKO. Childhood leukemia and lymphoma: African experience supports a role for environmental factors. In: Proceedings of the 103rd Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012:

46. Nkrumah F, Perkins I, Biggar R. Combination chemotherapy in abdominal Burkitt’s lymphoma. Cancer. 1977;40(4):1410-1416.

47. Hryniuk W. The importance of dose intensity in the outcome of chemotherapy. Important Adv Oncol. 1988:121-141.

48. Hryniuk W. Average relative dose intensity and the impact on design of clinical trials. 1987:65-74.

49. Ziegler JL. Burkitt’s lymphoma. Med Clin N Amer. 1977;61:1073-1082.

50. Forrest T. The political economy of civil rule and the economic crisis in Nigeria (1979–84). Review of African Political Economy. 1986;13(35):4-26.

51. Schatz SP. Pirate capitalism and the inert economy of Nigeria. The Journal of Modern African Studies. 1984;22(1):45-57.

52. Rimmer D. The overvalued currency and over-administered economy of Nigeria. African Affairs. 1985;84(336):435-446.

53. Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American statistical association. 1958;53(282):457-481.

54. Cox DR, Oakes D. Analysis of survival data. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1984.

55. Institute SAS. SAS/STAT user’s guide. vol 1&2. 6. SAS Publ.; 1989:1686.

56. Kumar P, Murphy FA. Francis Peyton Rous. Emerging infectious diseases. 2013;19(4):660.

57. Rettig RA. The story of the national cancer act of 1971. 1977.

58. Rettig RA. Cancer crusade: the story of the National Cancer Act of 1971. iUniverse; 2005.

59. Chabner BA, Roberts Jr TG. Chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2005;5(1):65-72.

60. Viviani S, Zinzani PL, Rambaldi A, et al. ABVD versus BEACOPP for Hodgkin’s lymphoma when high-dose salvage is planned. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(3):203-212.

61. Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2011;61(4)

62. André T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(19):3109-3116.

63. André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(23):2343-2351.

64. Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Ingle J, et al. Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcomes in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(3):509-518.

65. Group EBCTC. Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, Clarke M, Cutter D, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378 (9793):771-84.

66. Gennari A, Conte P, Rosso R, Orlandini C, Bruzzi P. Survival of metastatic breast carcinoma patients over a 20‐year period: A retrospective analysis based on individual patient data from six consecutive studies. Cancer. 2005;104(8):1742-1750.

67. Deininger M, O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, et al. International randomized study of interferon vs STI571 (IRIS) 8-year follow up: sustained survival and low risk for progression or events in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) treated with imatinib. Blood. 2009;114(22):1126.

68. Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin–paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(10):947-957.

69. Kwak EL, Bang Y-J, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non–small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(18):1693-1703.

70. Van Cutsem E, Siena S, Humblet Y, et al. An open-label, single-arm study assessing safety and efficacy of panitumumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard chemotherapy. Annals of Oncology. 2008;19(1):92-98.

71. Van Cutsem E, Peeters M, Siena S, et al. Open-label phase III trial of panitumumab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of clinical oncology. 2007;25(13):1658-1664.

72. Soria J-C, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. New England journal of medicine. 2018;378(2):113-125.

73. Ramalingam SS, Yang JC-H, Lee CK, et al. Osimertinib as first-line treatment of EGFR mutation–positive advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(9): 841-849.

74. Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Ahn M-J, et al. Osimertinib or platinum–pemetrexed in EGFR T790M–positive lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376(7):629-640.

75. Fu K, Xie F, Wang F, Fu L. Therapeutic strategies for EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer patients with osimertinib resistance. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2022;15(1):173.

76. Domingues B, Lopes JM, Soares P, Pópulo H. Melanoma treatment in review. ImmunoTargets and therapy. 2018:35-49.

77. Liu Q, Das M, Liu Y, Huang L. Targeted drug delivery to melanoma. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2018;127:208-221.

78. Mishra H, Mishra PK, Ekielski A, Jaggi M, Iqbal Z, Talegaonkar S. Melanoma treatment: from conventional to nanotechnology. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2018;144:2283-2302.

79. Kozyra P, Krasowska D, Pitucha M. New Potential Agents for Malignant Melanoma Treatment—Most Recent Studies 2020–2022. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(11):6084.

80. Mishra AK, Ali A, Dutta S, Banday S, Malonia SK. Emerging trends in immunotherapy for cancer. Diseases. 2022;10(3):60.

81. Yousefi H, Yuan J, Keshavarz-Fathi M, Murphy JF, Rezaei N. Immunotherapy of cancers comes of age. Expert review of clinical immunology. 2017;13(10):1001-1015.

82. Emens LA, Romero PJ, Anderson AC, et al. Challenges and opportunities in cancer immunotherapy: a Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) strategic vision. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer. 2024;12(6):e009063.

83. Brahmer JR, Govindan R, Anders RA, et al. The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer consensus statement on immunotherapy for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Journal for immunotherapy of cancer. 2018;6:1-15.

84. Kraehenbuehl L, Weng C-H, Eghbali S, Wolchok JD, Merghoub T. Enhancing immunotherapy in cancer by targeting emerging immunomodulatory pathways. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2022; 19(1):37-50.

85. Palumbo MO, Kavan P, Miller Jr WH, et al. Systemic cancer therapy: achievements and challenges that lie ahead. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2013;4:57.

86. Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Morales-Vasquez F, Hortobagyi GN. Overview of resistance to systemic therapy in patients with breast cancer. Breast cancer chemosensitivity. 2007:1-22.

87. Agarwal G, Ramakant P, Forgach ERS, et al. Breast cancer care in developing countries. World journal of surgery. 2009;33(10):2069-2076.

88. Unger-Saldaña K. Challenges to the early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in developing countries. World journal of clinical oncology. 2014 ;5(3):465. doi:doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.465

89. Jakesz R. Breast cancer in developing countries: challenges for multidisciplinary care. Breast Care. 2008;3(1):4-5.

90. Sarkar DK. Breast Cancer in Developing Countries: Issues and Solutions. Breast Diseases. CRC Press; 2024:212-214.

91. Vanderpuye V, Grover S, Hammad N, Simonds H, Olopade F, Stefan D. An update on the management of breast cancer in Africa. Infectious agents and cancer. 2017;12(1):1-12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-017-0124-y

92. Anderson BO, Braun S, Carlson RW, et al. Overview of breast health care guidelines for countries with limited resources. The breast journal. 2003;9(s2):S42-S50.

93. Pinkel D, Hernandez K, Borella L, et al. Drug dosage and remission duration in childhood lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 1971;27(2):247-256.

94. Samson MK, Rivkin SE, Jones SE, et al. Dose‐response and dose‐survival advantage for high versus low‐dose cisplatin combined with vinblastine and bleomycin in disseminated testicular cancer a southwest oncology group study. Cancer. 1984;53 (5):1029-1035.

95. Tannock IF, Boyd NF, DeBoer G, et al. A randomized trial of two dose levels of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil chemotherapy for patients with metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1988;6 (9):1377-87.

96. DeVita Jr VT, Hubbard SM, Longo DL. The chemotherapy of lymphomas: looking back, moving forward—the Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Foundation award lecture. Cancer research. 1987; 47(22):5810-5824.

97. Williams CKO, Liu L. Burkitt’s lymphoma: a human tumor model for studies of dose intensity and other chemotherapy principles. presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, Abstract #1178; 1996;

98. Carter CL, Allen C, Henson DE. Relation of tumor size, lymph node status, and survival in 24,740 breast cancer cases. Cancer. 1989;63 (1):181-7.

99. Holland JF, Frei E, 3rd, al. e, eds. Cancer Medicine. 4th ed. Williams & Wilkins; 1993. Surbone A, Gilewski TA, Norton L, eds. Cytokinetics.

100. Li MC, Hertz R, Spencer DB. Effect of methotrexate therapy upon choriocarcinoma and chorioadenoma. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1956;93 (2):361-366.

101. Ngoma T, Adde M, Durosinmi M, et al. Treatment of Burkitt lymphoma in equatorial Africa using a simple three‐drug combination followed by a salvage regimen for patients with persistent or recurrent disease. British journal of haematology. 2012;158(6):749-762.

102. Williams CK, Oyejide CO. Chemotherapeutic responsiveness of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in young Nigerians. West African Journal of Medicine. 1986;5(4):257-265.

103. Magrath I, Shanta V, Advani S, et al. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in countries with limited resources; lessons from use of a single protocol in India over a twenty year peroid. European journal of cancer. 2005;41(11):1570-1583.

104. Williams C. High-Dose Cytosine Arabinoside Chemotherapy of Burkitt Lymphoma: Advocating Sustainable Strategies for Capacity Building in Systemic Cancer Care in Nigeria. Chemo Open Access. 2015;4(167):2.

105. Howard SC, Lam CG, Arora RS. Cancer epidemiology and the “incidence gap” from non-diagnosis. Pediatric Hematology Oncology Journal. 2018;3(4):75-78.

106. Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, Frazier AL, Atun R. Estimating the total incidence of global childhood cancer: a simulation-based analysis. The Lancet Oncology. 2019;20(4):483-493.

107. Alwan A, MacLean DR. A review of non-communicable disease in low-and middle-income countries. International Health. 2009;1(1):3-9.

108. Bhuiyan MA, Galdes N, Cuschieri S, Hu P. A comparative systematic review of risk factors, prevalence, and challenges contributing to non-communicable diseases in South Asia, Africa, and Caribbeans. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2024;43(1):140.

109. Luna F, Luyckx VA. Why have non-communicable diseases been left behind? Asian bioethics review. 2020;12(1):5-25.

110. UNGAS. The UN General Assembly, 67/81 Global Health and Foreign Policy (United Nations, New York). 2012.

111. Klimo P, Connors JM. MOPP/ABV hybrid program: combination chemotherapy based on early introduction of seven effective drugs for advanced Hodgkin’s disease. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1985;3(9):1174-1182.

112. Thomas A, Teicher BA, Hassan R. Antibody–drug conjugates for cancer therapy. The Lancet Oncology. 2016;17(6):e254-e262.

113. Carter PJ, Senter PD. Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. The Cancer Journal. 2008;14(3):154-169.

114. Polakis P, Esbenshade TA. Antibody drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Pharmacological reviews. 2016;68(1):3-19.

115. Drago JZ, Modi S, Chandarlapaty S. Unlocking the potential of antibody–drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2021;18(6):327-344.

116. Ansell SM. Nivolumab in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2017;23(7):1623-1626.

117. Ramchandren R, Domingo-Domènech E, Rueda A, et al. Nivolumab for newly diagnosed advanced-stage classic Hodgkin lymphoma: safety and efficacy in the phase II CheckMate 205 study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37(23):1997-2007.

118. Bröckelmann PJ, Goergen H, Keller U, et al. Efficacy of nivolumab and AVD in early-stage unfavorable classic Hodgkin lymphoma: the randomized phase 2 German Hodgkin Study Group NIVAHL trial. JAMA oncology. 2020;6(6):872-880.

119. Williams CKO, Akingbehin NA, Seriki O, Folami AO. Efficacy of a high-dose cytosine arabinoside (ARA-C) containing regimen in the control of advanced Burkitt’s lymphoma (ADV-BL) – A preliminary assessment. 1985:

120. Ibrahim M, Abdullahi S, Hassan-Hanga F, Atanda A. Pattern of childhood malignant tumors at a teaching hospital in Kano, Northern Nigeria: A prospective study. Indian journal of cancer. 2014; 51(3):259.

121. Amusa Y, Adediran I, Akinpelu V, et al. Burkitt’s lymphoma of the head and neck region in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. West African journal of medicine. 2005;24(2):139-142.

122. Kagu M, Kagu B, Adeodu O, Akinola N, Adediran I, Salawu L. Determinants of survival in Nigerians with Burkitt’s lymphoma. African journal of medicine and medical sciences. 2004;33(3):195-200.

123. Meremikwu M, Ehiri J, Nkanga D, Udoh E, Ikpatt O, Alaje E. Socioeconomic constraints to effective management of Burkitt’s lymphoma in south‐eastern Nigeria. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2005;10(1):92-98.

124. Ugboko VI, Oginni FO, Adelusola KA, Durosinmi MA. Orofacial non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Nigerians. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2004;62(11):1347-1350.

125. Fasola F, Shokunbi W, Falade A. Factors determining the outcome of management of patients with Burkitt’s lymphoma at the University College Hospital Ibadan, Nigeria–an eleven year review. The Nigerian postgraduate medical journal. 2002;9(3):108-112.

126. Oji C, Ike I. Burkitt-Lymphom. Mund-, Kiefer-und Gesichtschirurgie. 1999;3(4):220-224.

127. Ekanem I, Asindi A, Ekwere P, Ikpatt N, Khalil M. Malignant childhood tumours in Calabar, Nigeria. African journal of medicine and medical sciences. 1992;21(2):63-69.

128. Oguonu T, Emodi I, Kaine W. Epidemiology of Burkitt’s lymphoma in Enugu, Nigeria. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics: International Child Health. 2002;22(4):369-374.

129. Durosinmi M, Adeodu O, Oyekunle A, Bolarinwa R, Olufemi A, Salawu L. Improved survival in patients with African Burkitt lymphoma: Experience in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. 2013:118.

130. Sambo L, Dangou J, Adebamowo C, et al. Cancer in Africa: a preventable public health crisis. Journal Africain du Cancer/African Journal of Cancer. 2012;4(2):127-136.