Iron Deficiency in Athletes: Impacts and Management

Iron deficiency of Sports Nutrition

Ryunosuke Takahashi1 and Takako Fujii2

- The Institute of Health and Sports Science, Chuo University, Tokyo, Japan

- Department of Sports and Medical Science, Graduate School of Emergency Medical System, Kokushikan University, Tokyo, Japan.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 October 2025

CITATION: Takahashi, R., and Fujii, T., 2025. Iron deficiency of Sports Nutrition. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(10). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i10.7039

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i10.7039

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Anemia resulting from iron deficiency is recognized as one of the most prevalent forms of malnutrition on a global scale. Iron is an essential metal that plays a key role in various biological processes, including the formation of hemoglobin, deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis, and mitochondrial respiration. However, mounting evidence indicates that excess iron in the body can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), which have been demonstrated to inflict harm on cells, tissues, and organs, resulting in deleterious effects. Consequently, merely augmenting iron intake does not invariably result in enhanced well-being. Therefore, it is imperative to maintain iron concentrations within a precise physiological range. In recent years, the relationship between hepcidin, which regulates iron content in the body, and inflammation, particularly the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6, has become the focus of significant research. However, a significant proportion of athletes manifest symptoms consistent with chronic inflammation rather than episodic inflammation. This paper provides a comprehensive overview of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in athletes and identifies research directions that may lead to new therapeutic possibilities.

Keywords: iron deficiency; hepcidin; anemia of chronic disease (ACD); hemojuvelin (HJV)

Introduction

Iron concentrations are subject to stringent regulation, maintained within a predetermined range. Iron is an essential nutrient that is primarily absorbed in the upper small intestine. A portion of the absorbed iron is stored in the liver, while the remainder is utilized by cellular enzymes involved in respiration and DNA synthesis. It has been determined that approximately 60–70% of iron plays a particularly important role in the process of erythropoiesis, which occurs in the bone marrow. This process contributes fundamentally to the oxygen-carrying capacity of newly formed red blood cells through hemoglobin function. The typical lifespan of these red blood cells is approximately 120 days. At this juncture, the cells undergo a process of senescence, which promotes regular turnover. The process under discussion occurs primarily in the spleen with the assistance of reticuloendothelial macrophages. These macrophages are responsible for the degradation of senescent cells and the recovery of useful components, such as iron from hemoglobin, during this process. Instead of excreting these components into the circulation, they utilize ferroportin, a protein also found in intestinal epithelial cells. This process ultimately enables the uptake of apotransferrin, which aids in the redistribution of recovered iron to systemic pathways. This ensures that losses are minimized under normal conditions, thereby ensuring continuous resource utilization without necessitating new dietary intake. These losses are primarily attributable to gastrointestinal cell shedding, with negligible traces of loss through urine and sweat. This finding underscores the reliance on existing endogenous resources and reinforces the closed-loop nature of global metabolic regulation. These systems function collectively to achieve tightly controlled distribution across defined physiological ranges. These ranges are meticulously maintained over the requisite time frames to ensure the seamless execution of diverse functions. According to the findings of Cappellini et al., there is evidence to suggest that the daily loss and utilization of iron may potentially exceed its absorption. Impairment of iron metabolism, particularly the processes of iron recycling from splenic macrophages and hepcidin-mediated iron absorption in the duodenum, can lead to iron deficiency. Hepcidin plays a critical role in iron homeostasis. Iron is imperative for transporting oxygen to muscles during periods of physical exertion, thereby facilitating the process of energy production. Consequently, studies have demonstrated that iron deficiency can result in impaired athletic performance in endurance sports. A multitude of physiological mechanisms have been postulated, particularly in the context of endurance athletes. Recent studies have indicated a correlation between the emergence of apathy-related symptoms and negative mood disorders. However, the precise mechanism underlying exercise-induced iron deficiency in athletes remains to be elucidated.

Iron Deficiency Among Athletes

Presently, the measurement of anemia is predominantly conducted through the assessment of hemoglobin concentration. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), anemia is characterized as a condition in which the concentration of hemoglobin falls below specific thresholds. For males, this threshold is defined as a concentration of less than 13 g/dl, while for females, it is set at 12.0 mg/dl. In recent years, blood ferritin levels, which reflect iron stores, have garnered attention for determining iron deficiency. The World Health Organization (WHO) establishes a serum ferritin concentration of 15 ng/mL as the cutoff value for iron deficiency in healthy individuals (10-59 years). Iron is crucial for the transport of oxygen to skeletal muscles during physical exertion and plays a vital role in energy production throughout exercise. Therefore, a deficiency in iron adversely affects athletic performance, especially in endurance sports. Various physiological mechanisms have been suggested to account for iron depletion during physical activity, including gastrointestinal bleeding, hemolysis related to impact (such as on the soles of the feet), insufficient dietary intake of iron, and losses through excessive sweating. Despite the prevalence of studies employing a serum ferritin cutoff value of >30 ng/mL, a broader range, such as 12–40 ng/mL, has been utilized in investigations focused on iron deficiency and metabolism. Additionally, a ferritin cutoff value of 50 ng/mL has been proposed as a criterion for the early detection of iron deficiency. Furthermore, Mielgo Ayuso et al. reported that the optimal cutoff value for diagnosing functional iron deficiency is 30–99 ng/mL, and that a serum ferritin level of 100 ng/mL or higher indicates adequate iron stores. The findings of this study indicate that employing a higher ferritin cutoff value may prove advantageous in the context of screening athletes for iron deficiency. According to the literature, the implementation of mild resistance exercise has been demonstrated to enhance latent iron deficiency in young women who do not receive iron supplements. In addition, Fujii et al. reported that mild resistance exercise can enhance the body’s ability to recycle iron. However, even if resistance exercise improves heme synthesis, it suggests that blood hemoglobin levels cannot be restored if iron, a component of hemoglobin, is not sufficiently supplied from diet or iron stores. Although some observations have been made on the effects of resistance exercise on iron nutrition in the body, the number of publications is significantly lower than that on aerobic exercise. Further research is needed to update the in vivo iron recycling capacity and the possibility of different iron uptakes depending on the type of exercise.

Athletes and Inflammation

Hepcidin consists of 25 amino acids and originates from an 84-amino acid prepropeptide. The predominant source of circulating hepcidin is hepatocytes; it is secreted into plasma bound to α2-macroglobulin. Hepcidin interacts with ferroportin on cell surfaces which leads to its internalization followed by lysosomal degradation of the hepcidin-ferroportin complex—thereby diminishing cellular exportation of iron. Since ferroportin facilitates the efflux of iron from enterocytes, hepatocytes, and macrophages, its internalization upon binding with hepcidin reduces systemic release of this essential mineral. Nonetheless, the most frequent cause of iron deficiency anemia is inadequate dietary iron. Other factors affecting iron metabolism, such as compromised recycling by macrophages and the spleen, along with hepcidin-mediated suppression of intestinal absorption of iron, also play significant roles. Hepcidin is a peptide hormone synthesized in the liver that serves as the primary regulator of systemic iron homeostasis. It modulates plasma iron levels by binding to ferroportin, which is the sole known cellular exporter of iron located on the basolateral membrane of enterocytes, macrophages, and hepatocytes. This interaction leads to ferroportin’s internalization and degradation within lysosomes, thus decreasing iron efflux into circulation. When body iron stores are adequate or during inflammatory conditions, hepcidin production increases while ferroportin levels diminish, inhibiting iron release. In contrast, when there is an increased demand for iron—such as during erythropoiesis or periods of deficiency—hepcidin expression declines allowing ferroportin to facilitate greater transport of iron. Under typical circumstances, this regulatory mechanism ensures stable blood concentrations of iron. However, excessive intake or inflammatory responses can lead to elevated hepcidin levels resulting in functional iron deficiency; in this state, excess iron is sequestered within storage sites and becomes unavailable for physiological processes. Consequently, measuring circulating hepcidin levels can be instrumental in evaluating whether iron metabolism operates effectively. Exercise also impacts hepcidin dynamics. Research indicates that IL-6 concentrations rise sharply post-exercise with a subsequent increase in hepcidin expression occurring approximately three hours later. Recent studies have concentrated on strategies—including nutritional interventions—to manage these post-exercise variations in hepcidin to enhance both performance and recovery through improved availability of iron. While hepatocytes are primarily responsible for producing hepcidin, it is also expressed by cardiomyocytes where it predominantly functions within cardiac tissue. Essentially, liver-derived hepcidin regulates systemic iron metabolism whereas cardiac-specific hepcidin manages local myocardial homeostasis. This meticulous regulation contributes significantly to sustaining normal cardiac function. These insights indicate that the localized cardiac interaction between hepcidin and ferroportin is crucial for maintaining cardiomyocyte-specific iron balance and safeguarding heart function. In summary, hepcidin plays a pivotal role in the regulation of iron metabolism at both the systemic and tissue-specific levels. At a systemic level, it contributes to the maintenance of overall balance by lowering serum concentrations of iron while inhibiting intestinal absorption and regulating release from hepatic cells and macrophages. Conversely, the local production of hepcidin within specific organs, such as the heart, ensures targeted regulation necessary for optimal organ functionality. The mechanisms that govern hepcidin expression are intricate, involving several genes and pathways. The following regulatory pathways have been identified as key players in the complex network of regulatory processes: the BMP/SMAD signaling cascade and the HFE/TFR2 pathways. In addition, the expression of the gene in question has been shown to be modulated by inflammatory states, including anemia associated with chronic disease, through IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathways.

Athlete and Anemia of chronic disease (ACD)

It is well established that athletes frequently experience exercise-induced systemic inflammation, which is characterized by a chronic inflammatory state. The development of chronic inflammatory diseases (CIDs) is attributed to an overproduction of hepcidin, a pivotal factor in the pathophysiology of anemia. Moreover, the sustained production of inflammatory cytokines can result in anemia of chronic disease (ACD). In such cases, multiple signaling pathways interact in a complex manner to control hepcidin expression. The aforementioned pathways include the BMP/SMAD, HFE-TFR2, and IL-6/STAT3 pathways. In particular, hemojuvelin (HJV/RGMc), a member of the repulsive guidance molecule (RGM) family, has been identified as a key regulator of hepcidin expression. HJV manifests in two distinct forms: membrane-bound (m-HJV) and soluble (s-HJV). The function of m-HJV is to serve as a BMP co-receptor, thereby acting as a pivotal regulator of hepcidin expression, demonstrating a positive regulatory effect on hepcidin expression. Conversely, s-HJV has been identified as a negative regulator of hepcidin expression by inhibiting the BMP/SMAD signaling pathway. During inflammatory responses, hepcidin expression is induced by activation of the IL-6/STAT3 pathway. However, the BMP/SMAD pathway is also imperative for this process. HJV has been demonstrated to play a pivotal role in the interaction between these pathways, contributing to the induction of hepcidin expression in ACD. Subsequent studies will offer further insight into the roles of ACD and HJV. The potential of HJV in regulating hepcidin expression and its role in inflammatory diseases require further elucidation. The findings from these studies may contribute to a more profound understanding of the pathophysiology of ACD. This may facilitate the identification of methods to prevent iron deficiency anemia and enhance exercise capacity.

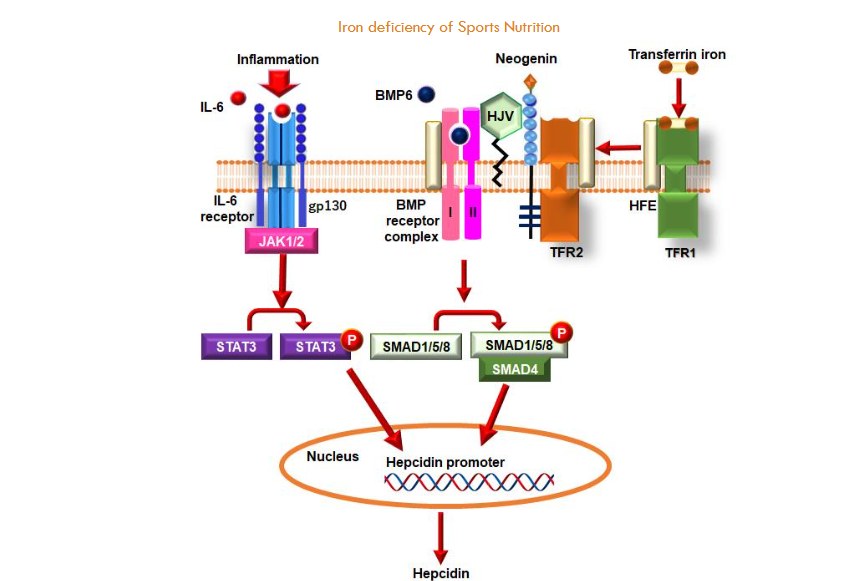

This section delineates the principal regulatory pathways that govern hepcidin expression in the context of inflammatory states and iron concentrations within the body. The expression of hepcidin is predominantly controlled by two types of pathways: those related to inflammation (notably the IL-6/STAT3 pathway) and those that sense iron levels (such as BMP/SMAD and HFE/TFR2 pathways). Within the context of inflammation, interleukin-6 (IL-6), a product of inflammatory responses, binds to its receptors, including gp130, thereby activating JAK1/2. This activation results in the phosphorylation of STAT3, which subsequently enters the nucleus and attaches to the hepcidin promoter to initiate transcription. In contrast, within iron-sensing mechanisms, BMP6 engages with the BMP receptor complex, resulting in the phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8. The phosphorylated SMAD proteins form a complex with SMAD4 and translocate into the nucleus, where they also bind to the hepcidin promoter. In this instance, HJV functions as a co-receptor for BMP receptors, thereby amplifying BMP signaling. Additionally, Neogenin from the RGM family binds to HJV, contributing to this regulatory process. Upon the binding of transferrin-bound iron to TFR1, a dissociation of HFE from TFR1 occurs, concomitant with its association with TFR2. This interaction exerts a regulatory influence on HJV and BMP receptor complexes, thereby facilitating hepcidin expression through the process of SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation. Furthermore, HFE directly engages with ALK3, a type I BMP receptor. It has been demonstrated that HFE inhibits ALK3’s ubiquitination as well as its proteasomal degradation, while enhancing its protein levels and promoting its relocation to the cell surface. The BMP/SMAD pathway exhibits a high degree of interaction with the IL-6/STAT3 pathway. The response elements for both STAT3 and BMP on the hepcidin promoter are situated in close proximity, indicating that an active BMP/SMAD pathway is imperative for the complete activation of hepcidin expression induced by IL-6 signaling. Therefore, it can be inferred that the BMP/SMAD pathway may prepare or prime the hepcidin promoter for optimal synthesis activation when stimulated by IL-6. The collaborative function of these pathways ensures meticulous regulation of hepcidin expression.

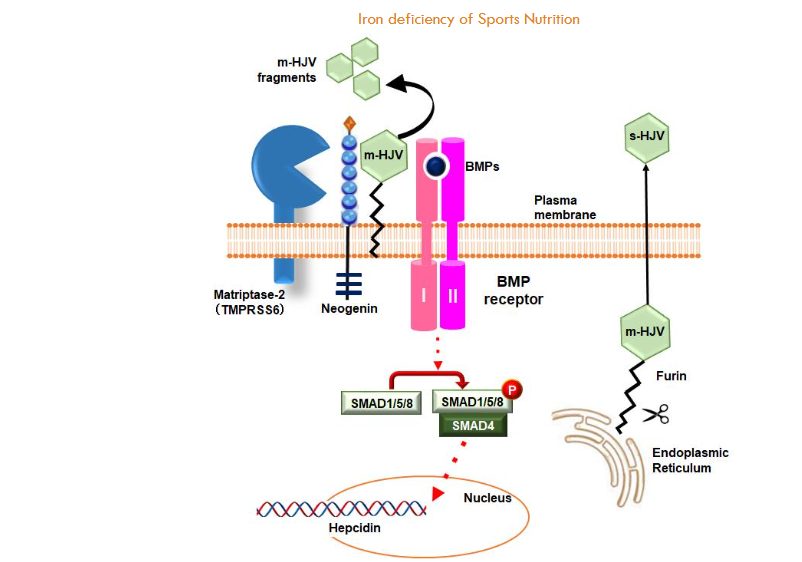

Membrane-bound HJVs (m-HJVs) have been identified as critical players in the regulation of BMP signaling, suggesting a pivotal role for these membrane-bound HJVs in the context of cellular processes. The process of signal transduction is initiated when BMPs bind to their respective receptors, leading to their activation. This, in turn, results in the phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8. These phosphorylated proteins subsequently bind with SMAD4, forming a complex that translocates to the nucleus to promote the transcription of hepcidin genes. The interaction between Neogenin and m-HJV is imperative for the regulation of this sequence of hepcidin expression. Consequently, the cleavage of m-HJV by Matriptase-2 (TMPRSS6) has been shown to inhibit hepcidin expression. The presence of m-HJV along with the Neogenin and TMPRSS6 protein complex facilitates this cleavage process by TMPRSS6. The accompanying diagram illustrates the m-HJV fragments produced from this cleavage event, with green hexagons denoting these fragments. Conversely, soluble HJV (s-HJV) functions as an antagonist within BMP signaling pathways. Furin cleaves HJV within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), resulting in the formation of s-HJV. This soluble form functions as a decoy receptor, impeding BMPs from binding to m-HJV and consequently hindering hepcidin expression. In essence, s-HJV interferes with the BMP/SMAD signaling pathway, resulting in a decrease in hepcidin expression.

Future research

Hepcidin exerts a pivotal function in the pathophysiology of ACD by modulating systemic iron homeostasis. Hepcidin has been shown to bind to ferroportin, promoting its internalization and subsequent degradation, thereby reducing iron efflux from cells. In ACD, the persistent inflammation that characterizes this condition has been shown to increase hepcidin production, which in turn reduces the amount of iron available for erythropoiesis and may lead to the development of anemia. The regulation of hepcidin expression is intricate and involves multiple signaling pathways, including the BMP/SMAD pathway, the IL-6/STAT3 pathway, and the HFE-TFR2 pathway. Hemojuvelin (HJV), also known as repulsion-inducing molecule C (RGMc) or haemochromatosis type 2 protein (HFE2), plays an important role in regulating these pathways and ultimately hepcidin expression. While the role of HJV in hepcidin regulation is not a novel concept, it is frequently disregarded in the domain of sports nutrition. Indeed, a considerable body of research has been dedicated to investigating the relationship between hepcidin and IL-6, as well as their interaction with nutrients. We hypothesize that the development of novel methodologies to prevent anemia associated with HJV will prove advantageous not only for athletes but also for the general population.

Conclusion

The present review focuses on the issue of iron deficiency in athletes. A substantial body of research has previously examined the impact of physical activity on iron status within the human body. The present study focused on the relationship between hepcidin and IL-6. However, it is imperative to acknowledge that there exist three predominant pathways for hepcidin expression, and future research endeavors should prioritize the elucidation of these pathways.

Research limitations

The limitation of this review is that research into the effect of resistance exercise on improving iron stores has only been conducted in animals. Although one report was cited in the text, no other human studies on iron and resistance exercise were found. We believe that careful consideration is needed when applying the iron recycling effect of resistance exercise to athletes.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, TF; Review of bibliographies, TF; Creation of figures, TF; Writing—review and editing, RT and TF. All authors have read and agreed to the published version ferritin manuscript.

Funding: The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Date Availability Statement: All information and findings presented in this review are based on previously published literature and are cited throughout the manuscript. No new datasets were generated or analyzed in this study.

References

- Lee PL, Beutler E. Regulation of hepcidin and iron-overload disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:489-515. doi:10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092205

- Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Camaschella C. Two to tango: regulation of Mammalian iron metabolism. Cell. 2010;142(1):24-38. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.028

- Ganz T, Nemeth E. Iron homeostasis in host defence and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(8):500-510. doi:10.1038/nri3863

- Kautz L, Jung G, Valore EV, Rivella S, Nemeth E, Ganz T. Identification of erythroferrone as an erythroid regulator of iron metabolism. Nat Genet. 2014;46(7):678-684. doi:10.1038/ng.2996

- Kohgo Y, Ikuta K, Ohtake T, Torimoto Y, Kato J. Body iron metabolism and pathophysiology of iron overload. Int J Hematol. 2008;88(1):7-15. doi:10.1007/s12185-008-0120-5

- Ganz T. Systemic iron homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(4):1721-1741. doi:10.1152/physrev.00008.2013

- Brune M, Magnusson B, Persson H, Hallberg L. Iron losses in sweat. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986;43(3):438-443. doi:10.1093/ajcn/43.3.438

- Scrimshaw NS. Functional consequences of iron deficiency in human populations. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 1984;30(1):47-63. doi:10.3177/jnsv.30.47

- Deldicque L, Francaux M. Recommendations for Healthy Nutrition in Female Endurance Runners: An Update. Front Nutr. 2015;2:17. Published 2015 May 26. doi:10.3389/fnut.2015.00017

- Varga E, Pap R, Jánosa G, Sipos K, Pandur E. IL-6 Regulates Hepcidin Expression Via the BMP/SMAD Pathway by Altering BMP6, TMPRSS6 and TfR2 Expressions at Normal and Inflammatory Conditions in BV2 Microglia. Neurochem Res. 2021;46(5):1224-1238. doi:10.1007/s11064-021-03322-0

- Peeling P, Dawson B, Goodman C, et al. Effects of exercise on hepcidin response and iron metabolism during recovery. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2009;19(6):583-597. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.19.6.583

- Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(10):a016295. Published 2014 Sep 4. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016295

- Sawada T, Konomi A, Yokoi K. Erratum to: Iron Deficiency Without Anemia Is Associated with Anger and Fatigue in Young Japanese Women. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2015;168(2):520-521. doi:10.1007/s12011-015-0531-0

- Sim M, Garvican-Lewis LA, Cox GR, et al. Iron considerations for the athlete: a narrative review. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2019;119(7):1463-1478. doi:10.1007/s00421-019-04157-y

- WHO. Prevalence of anemia in women of reproductive age (aged 15–49) (%). Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator

- Stewart JG, Ahlquist DA, McGill DB, Ilstrup DM, Schwartz S, Owen RA. Gastrointestinal blood loss and anemia in runners. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100(6):843-845. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-100-6-843

- Tobin BW, Beard JL. Interactions of iron deficiency and exercise training in male Sprague-Dawley rats: ferrokinetics and hematology. J Nutr. 1989;119(9):1340-1347. doi:10.1093/jn/119.9.1340

- Ehn L, Carlmark B, Höglund S. Iron status in athletes involved in intense physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1980;12(1):61-64.

- Sacks D, Baxter B, Campbell BCV, et al. Multisociety Consensus Quality Improvement Revised Consensus Statement for Endovascular Therapy of Acute Ischemic Stroke: From the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS), American Society of Neuroradiology (ASNR), Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe (CIRSE), Canadian Interventional Radiology Association (CIRA), Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS), European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT), European Society of Neuroradiology (ESNR), European Stroke Organization (ESO), Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery (SNIS), and World Stroke Organization (WSO). J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29(4):441-453. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2017.11.026

- Iancu TC. Ferritin and hemosiderin in pathological tissues. Electron Microsc Rev. 1992;5(2):209-229. doi:10.1016/0892-0354(92)90011-e

- Galetti V, Stoffel NU, Sieber C, Zeder C, Moretti D, Zimmermann MB. Threshold ferritin and hepcidin concentrations indicating early iron deficiency in young women based on upregulation of iron absorption. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101052. Published 2021 Jul 31. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101052

- Nachtigall D, Nielsen P, Fischer R, Engelhardt R, Gabbe EE. Iron deficiency in distance runners. A reinvestigation using Fe-labelling and non-invasive liver iron quantification. Int J Sports Med. 1996;17(7):473-479. doi:10.1055/s-2007-972881

- Reinke S, Taylor WR, Duda GN, et al. Absolute and functional iron deficiency in professional athletes during training and recovery. Int J Cardiol. 2012;156(2):186-191. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.10.139

- Hinton PS. Iron and the endurance athlete. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39(9):1012-1018. doi:10.1139/apnm-2014-0147

- Mielgo-Ayuso J, Zourdos MC, Calleja-González J, Córdova A, Fernandez-Lázaro D, Caballero-García A. Eleven Weeks of Iron Supplementation Does Not Maintain Iron Status for an Entire Competitive Season in Elite Female Volleyball Players: A Follow-Up Study. Nutrients. 2018;10(10):1526. Published 2018 Oct 17. doi:10.3390/nu10101526

- Matsuo, T.S., H. Suzuki, M., Dubbell exercise improves non-anemic iron deficiency in young women without iron supplementation. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology 2002. 48(2): p. 161–164.

- Fujii T, Matsuo T, Okamura K. Effects of resistance exercise on iron absorption and balance in iron-deficient rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;161(1):101-106. doi:10.1007/s12011-014-0075-8

- Park CH, Valore EV, Waring AJ, Ganz T. Hepcidin, a urinary antimicrobial peptide synthesized in the liver. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(11):7806-7810. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008922200

- Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, et al. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science. 2004;306(5704):2090-2093. doi:10.1126/science.1104742

- Ganz T. Iron homeostasis: fitting the puzzle pieces together. Cell Metab. 2008;7(4):288-290. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.008

- McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, de Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, 1993-2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(4):444-454. doi:10.1017/S1368980008002401

- Cappellini MD, Musallam KM, Taher AT. Iron deficiency anaemia revisited. J Intern Med. 2020;287(2):153-170. doi:10.1111/joim.13004

- Paul BT, Manz DH, Torti FM, Torti SV. Mitochondria and Iron: current questions. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017;10(1):65-79. doi:10.1080/17474086.2016.1268047

- Merler E. L’incidenza del mesotelioma diminuisce parallelamente alla diminuzione o interruzione dell’esposizione ad amianto: una conferma della relazione dose-risposta, non priva di implicazioni preventive [Mesothelioma incidence decreases parallel to asbestos exposure decrement or interruption: a confirmation of a dose-response relationship, with implications in public health]. Epidemiol Prev. 2007;31(4 Suppl 1):46-52.

- Lakhal-Littleton S, Wolna M, Chung YJ, et al. An essential cell-autonomous role for hepcidin in cardiac iron homeostasis. Elife. 2016;5:e19804. Published 2016 Nov 29. doi:10.7554/eLife.19804

- Ganz T. Hepcidin and iron regulation, 10 years later. Blood. 2011;117(17):4425-4433. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-01-258467

- Nemeth E, Rivera S, Gabayan V, et al. IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(9):1271-1276. doi:10.1172/JCI20945

- Babitt JL, Huang FW, Wrighting DM, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling by hemojuvelin regulates hepcidin expression. Nat Genet. 2006;38(5):531-539. doi:10.1038/ng1777

- Meynard D, Kautz L, Darnaud V, Canonne-Hergaux F, Coppin H, Roth MP. Lack of the bone morphogenetic protein BMP6 induces massive iron overload. Nat Genet. 2009;41(4):478-481. doi:10.1038/ng.320

- Monnier PP, Sierra A, Macchi P, et al. RGM is a repulsive guidance molecule for retinal axons. Nature. 2002;419(6905):392-395. doi:10.1038/nature01041

- Hata K, Fujitani M, Yasuda Y, et al. RGMa inhibition promotes axonal growth and recovery after spinal cord injury. J Cell Biol. 2006;173(1):47-58. doi:10.1083/jcb.200508143

- Samad TA, Srinivasan A, Karchewski LA, et al. DRAGON: a member of the repulsive guidance molecule-related family of neuronal- and muscle-expressed membrane proteins is regulated by DRG11 and has neuronal adhesive properties. J Neurosci. 2004;24(8):2027-2036. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4115-03.2004

- Fujii, T. Kobayashi, K. Kaneko, M. Osana, S. Tsai, CT. Ito, S. Hata, K. RGM Family Involved in the Regulation of Hepcidin Expression in Anemia of Chronic Disease. Immuno, 2024. 4(3): p. 266–285. https://doi.org/10.3390/immuno4030017