Community-Level One Health: Strategies for Implementation

A Strategic Action Model for Understanding, Designing, and Achieving Community-level One Health Implementation

Nochiketa Mohanty

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6238-1342

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 October 2025

CITATION: MOHANTY, Nochiketa. A Strategic Action Model for Understanding, Designing, and Achieving Community-level One Health Implementation. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 10, oct. 2025. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/7040>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i10.7040.

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Background: The One Health approach, linking human, animal, and environmental health, is essential for addressing threats such as zoonotic disease and antimicrobial resistance. However, its application at the community level is limited by the absence of clear operational guidance, leaving local populations at risk. There is a need for an actionable framework that supports communities in translating One Health into practice.

Objectives: This article presents a comprehensive roadmap for community-level One Health implementation developed through synthesis of published literature, global frameworks, and case studies. We identify community health priorities, describe mixed-methods needs assessment approaches, outline implementation barriers, recommend evidence-based strategies, and define essential competencies for community-based One Health workforce development.

Methods: A narrative review approach synthesized evidence from peer-reviewed literature, gray literature, and organizational guidelines including WHO, FAO, and WOAH frameworks. Community needs assessment methods were evaluated across quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods, and participatory approaches. Case studies from Rwanda, Washington State, Uganda, and India informed practical recommendations.

Results: Key community needs include local zoonotic risk assessment, accessible veterinary services, environmental monitoring, integrated syndromic surveillance, and workforce capacity building. Major barriers encompass sectoral silos, weak communication systems, short-term funding, limited community engagement, and inadequate multidisciplinary training. Evidence-based strategies include establishing multisectoral coordination mechanisms, implementing lightweight integrated data systems, developing layered workforce training programs, utilizing participatory co-design approaches, securing sustainable financing, and building community trust through transparent processes. A competency framework outlines essential skills spanning risk communication, surveillance, environmental assessment, animal health basics, coordination, and cultural competence.

Conclusions: Effective One Health implementation depends on community-level action guided by locally-relevant, evidence-based frameworks. By systematically assessing community needs and developing collaborative, context-specific solutions, policymakers and program managers can strengthen health system resilience and pandemic preparedness. The proposed roadmap provides practical guidance for translating One Health principles into community action, addressing interconnected health challenges through sustained intersectoral partnerships and community empowerment.

Keywords: One Health, community engagement, zoonotic diseases, surveillance, implementation science, participatory assessment

Background

The One Health concept integrates multiple disciplines to promote health across people, animals, and environments. This approach recognizes that human and animal health are closely linked through shared environments and ecosystems. (WHO, 2024) The Quadripartite organizations have established a global framework emphasizing community-level implementation as essential for pandemic preparedness and health security. (WHO, FAO, WOAH, UNEP, 2022) Everyday interactions between people, domestic animals, wildlife and natural resources create unique risk patterns. For example, rural farming villages may face zoonotic diseases from close livestock contact, while urban slums may suffer from contaminated water or air pollution. In each setting, local factors (cultural practices, economic activity, ecology) shape the most pressing health threats. Implementing One Health at the community level requires tailored guidance that is currently scarce in practice. In many regions especially in developing countries local efforts operate without clear frameworks for integrating human, animal, and environmental health. This gap can leave communities vulnerable to preventable threats. The world remains vulnerable to future outbreaks unless practical One Health frameworks are translated into action with community involvement. Recent systematic reviews highlight that effective One Health implementation requires evidence-based community engagement strategies and local capacity building. (Milazzo, et al., 2025)

A community focused One Health framework can help policymakers and program administrators prioritize local risks, coordinate multisectoral efforts, and mobilize resources where they are most needed. By offering a detailed implementation framework, this article intends to provide a roadmap that fills a critical void and empowers local stakeholders to address zoonoses, environmental hazards, and related health challenges more effectively. Effective interventions must be tailored to local priorities and capacities. Central to this is recognizing and adapting to unique community requirements, ensuring interventions match local contexts and capabilities. These and other experiences highlight that a one-size-fits-all approach is insufficient: policies must align with on-the-ground realities. A uniform strategy overlooks variations what may be relevant for Washington State may not be applicable for a province in an African country or a state in India, as emphasized in regional implementation analyses. (Samhouri, et al., 2025)

Objectives

This article draws on global literature and case studies to synthesize (1) the key community needs for One Health, (2) methods to assess those needs, (3) current gaps hindering understanding, (4) recommendations to address gaps, and (5) essential community-level skills. By covering all whats and hows, this roadmap aims to guide local officials and health program administrators in implementing One Health in their communities.

1. Community Needs in One Health

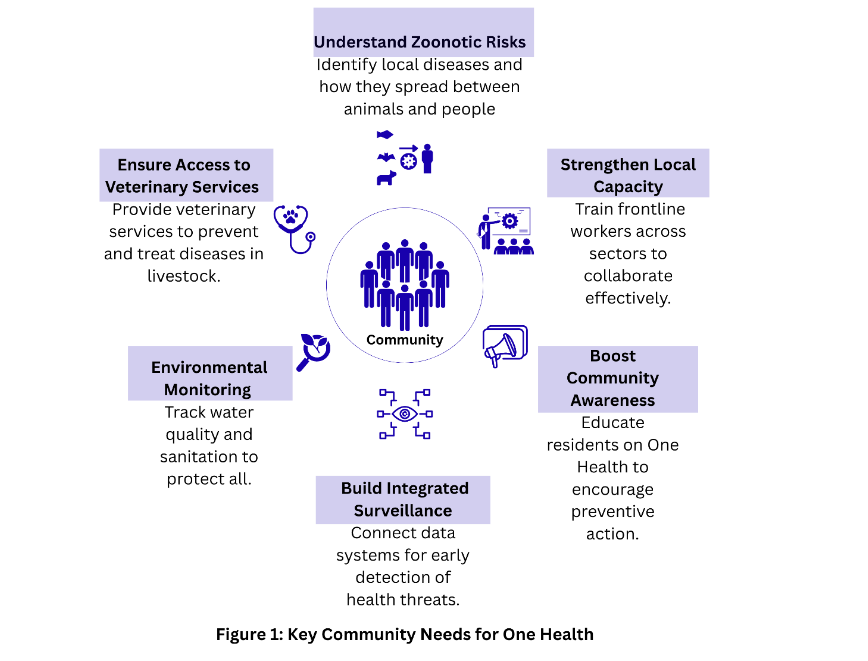

Critical community needs in One Health span human, animal, and environmental domains as per global frameworks and local studies include:

- Local Disease Patterns and Zoonotic Risks: Communities need detailed data on prevalent diseases and transmission drivers. As populations grow and land use changes, infectious disease burdens tend to rise. Identifying which zoonoses (e.g. leptospirosis, scrub typhus, influenza) are common locally and which animal reservoirs or vectors are involved is essential for targeted control. (Di Bari, et al., 2023) (Desvars-Larrive, et al., 2024)

- Access to Veterinary and Animal Health Services: Many communities lack easy access to veterinary services, trained animal health workers or vaccines. This gap increases risks of zoonoses and food-borne illness. Rural villages with no nearby veterinarians may see unchecked animal disease outbreaks that can spill into humans. Building local veterinary capacity or access through mobile or tele-health veterinary services is thus needed.

- Environmental Health Monitoring: Communities need to monitor environmental factors that directly impact animal and human well-being such as local water quality, sanitation, air quality, and land-use changes (like deforestation). Equipping communities with tools and training human resources such as Environmental Health Practitioners to track such environmental hazards can help prevent disease outbreaks. (David Musoke, 2016), (Buregyeya, et al., 2020). Environmental monitoring systems must integrate antimicrobial resistance surveillance (McEwen & Collignon, 2018) and climate-sensitive health indicators (Yang, et al., 2020) to address emerging threats. Environmental Health Practitioners (EHPs) play important roles in disease surveillance, prevention and control within One Health frameworks. In Uganda, Environmental Health Practitioners carry out duties including inspection of animals before slaughter, disease surveillance, outbreak investigation and control of zoonoses. EHPs also play an important role in prevention, detection and abatement of microbial and chemical pollution of land, air and water sources that threaten both animal and human health. Environmental Health professionals should be involved as stakeholders in local, national and global One Health initiatives. (Buregyeya, et al., 2020)

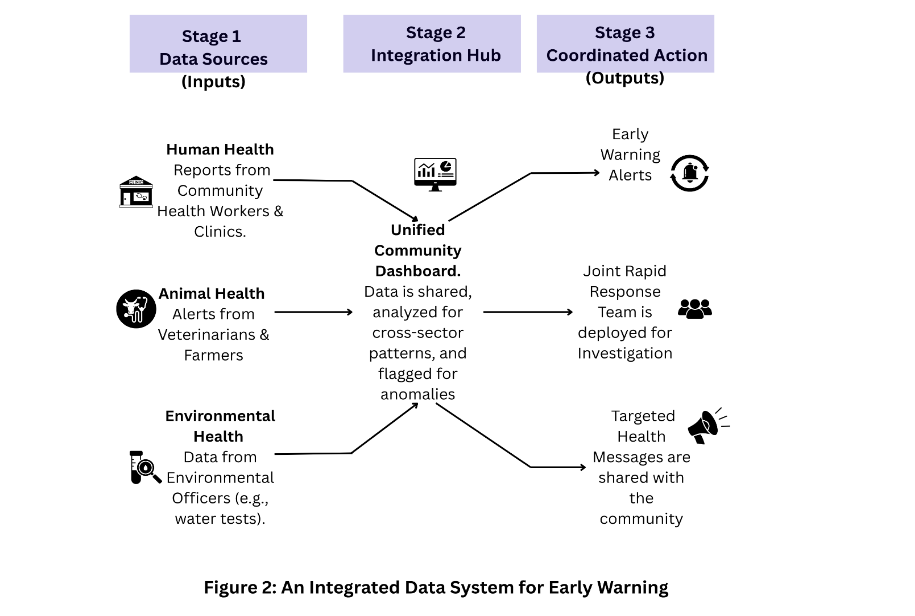

- Integrated Syndromic Surveillance Systems: Detecting threats early requires data systems that bridge human, animal and environmental sectors. For disease outbreaks to be detected in a timely manner, syndromic data must be both available and integrated across sectors. When data are siloed in separate ministries or databases, warning signs can be missed. Advanced surveillance frameworks emphasize the need for holistic data integration across sectors, with early warning capabilities that can detect patterns before outbreaks occur.

Figure 1: Integrated Syndromic Surveillance Systems (Singh, et al., 2024) At the community level it allows authorities to spot, say, a spike in animal respiratory illness before human cases emerge. For efficient early warning systems and detection, community level awareness of symptoms across human and animals and reporting is essential, supported by systematic sentinel surveillance networks. (Hassan, Balogh, & Winkler, 2023)

- Community awareness on One Health Principles: Public awareness of how human, animal and environmental health interconnects enables preventive behaviors. Communities benefit when people understand the interconnections such as understanding that vaccinating livestock protects both animal and human health, or that proper disposal of animal waste reduces waterborne disease. Ongoing education campaigns that are tailored to local languages and customs help residents adopt One Health practices.

- Capacity Building for Local Health Workers: Frontline workers such as Community Health Workers (CHWs), veterinarians, and environmental officers often work in silos and need cross-disciplinary skills and resources. In many places, CHWs are trained only for human disease, leaving them ill-prepared to recognize animal health signs or environmental contamination. Similarly, Animal health workers in the community would be able to recognize and alert symptoms among animal handlers during outbreaks in animals if they are oriented on human diseases. Effective One Health demands training CHWs in zoonotic disease surveillance, basic veterinary care, and environmental risk assessment, as demonstrated in multi-country agricultural and livestock system implementations. (Nguyen-Viet, et al., 2025) For example, Rwanda’s use of a decentralized network of CHWs and animal-health workers as local sentinels has proven effective in monitoring zoonotic outbreaks. (Henley, Igihozo, & Wotton, 2021)

2. Methods to Understand Community Needs in One Health

Different communities will prioritize these needs differently, hence any assessment must be context-specific to address local realities. (Ravaghi, et al., 2023) Urban areas may emphasize pollution control, while rural areas may focus on livestock health. Overall, addressing these needs will lay the groundwork for community-level One Health action. Community needs may be assessed through quantitative, qualitative, mixed and participatory approaches. (Ravaghi, et al., 2023) Combining methods ensures that data-driven trends are enriched by local knowledge and buy-in. Below is a brief exploration of these methodologies:

QUANTITATIVE METHODS

These provide scalable data on patterns:

- Surveys: Includes collecting demographics, health status, and service access via interviews or online platforms.

- Sampling Techniques: Random sampling ensures representativeness, but convenience sampling is common. This may be mitigated by incentives or multiple channels.

- Data Analysis: Descriptive statistics is employed to compare local indicators to benchmarks thus identifying gaps like service coverage.

QUALITATIVE METHODS

These are used to capture nuanced perspectives, especially from vulnerable groups:

- Key Informant Interviews: These are conducted with leaders such as tribal representatives or workers to uncover issues like cultural risks.

- Focus Groups: These are conducted through discussions among smaller group of relevant community representatives to identify barriers and priorities.

- Community Forums: These are conducted to ensure broader participation for consensus on needs like surveillance systems.

MIXED-METHODS APPROACHES

Combining both Quantitative and Qualitative approaches yields depth and breadth:

- Triangulation Designs: Employs a mix of quantitative and qualitative approaches for different purposes such as Surveys for trends, followed by interviews for causes to assess zoonotic risks.

- Explanatory Designs: Employs quantitative approach first to spot issues, then qualitative for exploration.

PARTICIPATORY APPROACHES

Participatory approaches empower communities for ownership. This includes:

- Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR): This involves locals and diverse representatives from the community in design and data collection. Successful community-based participatory approaches have been implemented for One Health education and zoonotic risk assessment, demonstrating the value of local knowledge integration. (Berrian, et al., 2017) (Guenin, et al., 2022)

- Participatory Action Research (PAR): This focuses on co-developing solutions for issues like antimicrobial resistance.

While participatory approaches lend greater community ownership and more sustainable interventions, the main challenges of these methods are that they require time and resources and a commitment to power-sharing. By combining these methods surveys, interviews, participatory workshops, and assessment tools communities can gather rich, actionable information. The selection of appropriate assessment tools should be guided by systematic inventories of available One Health instruments and evidence-based tool selection criteria. (Behravesh, et al., 2024) (Yasobant, Lekha, & Saxena, 2024) The approach should always include multiple voices and data types to ensure the final priorities and plans reflect local realities. These methods are further illustrated in the table below.

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS OF PARTICIPATORY APPROACH FOR ONE HEALTH:

The Washington State One Health Needs Assessment: The Washington State One Health Needs Assessment (One Health Needs Assessment Report, 2023) demonstrates a mixed participatory approach combining surveys, multi-sector workshops, and qualitative analysis to generate actionable insights for One Health implementation. In Washington State’s 2023 One Health Needs Assessment, an advisory committee of representatives from state agencies, local public health, academia, and development organizations helped define established frameworks like the One Health Zoonotic Disease Prioritization (OHZDP) and One Health Systems Mapping and Analysis Resource Toolkit (OH-SMART). The OH-SMART is an interactive process that fosters working across organizational and disciplinary lines when preparing or responding to disease outbreaks. (Vesterinen, et al., 2019) The OHZDP process uses a multisectoral, One Health approach to prioritize zoonotic diseases of greatest concern. (Varela, et al., 2022) In a two-day workshop, attendees were selected into working groups around each topic to discuss strengths, gaps and needed actions. Discussions were structured by a prioritization matrix considering impact (like equity) and readiness (policy, capacity). Qualitative notes from group reports were analyzed to identify common themes, and participants also scored each action. The exercise culminated in ranking One Health actions by priority through a prioritization matrix considering impact and readiness factors. This mixed participatory approach combining surveys, multi-sector workshops, and qualitative analysis generated a roadmap guiding future program and policy decisions. OH-SMART has been successfully used in 18 countries to tackle ongoing and emerging One Health challenges ranging from emerging and endemic zoonotic diseases to disaster preparedness and antimicrobial resistance action planning. (Vesterinen, et al., 2019)

| Method category | Purpose / what it answers | Key techniques & tools | Strengths | Limitations & mitigations | Typical examples / outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | What scale, prevalence, coverage, hotspots | Structured surveys (household, phone, online), sampling (random, cluster, convenience), routine data extraction, descriptive & comparative statistics | Scalable, comparable, supports prioritization & benchmarking | Sampling bias / low response mitigate with incentives, multiple channels, local surveyors, language support; needs good sample design | Livestock ownership rates; incidence of zoonoses; water contamination measures; service coverage maps |

| Qualitative | Why perceptions, drivers, barriers, context | Key informant interviews (leaders, vets, health workers, traders), focus groups (farmers, mothers, youth), community forums / town halls | Rich context, uncovers cultural practices, includes vulnerable voices | Time-intensive; smaller samples mitigate with purposive sampling, local facilitators, combine with surveys for validation | Explanations of risky behaviours, community priorities, barriers to using services |

| Mixed-methods | Combine breadth + depth; triangulate findings | Explanatory sequential (survey → interviews/FGDs), triangulation designs, integrated analysis, participatory mapping (cases + drawn risk maps) | Validates results, produces evidence-based, community-endorsed recommendations | More complex and resource-intensive mitigate via phased design, targeted sampling and clear analytic plan | Survey identifying respiratory hotspots followed by FGDs to probe causes; integrated risk maps |

| Participatory | Co-creation, ownership, actionable solutions | CBPR (community co-design & data collection), PAR (action cycles), workshops & stakeholder working groups, citizen science, priority-ranking exercises | Builds trust, cultural fit, empowers marginalized groups, increases uptake | Can raise expectations; time & facilitation needs mitigate with clear roles, quick wins, capacity building, transparent feedback loops | Community-led surveillance, priority-ranked intervention lists, data interoperability working groups |

Adapting the FAO One Health Assessment Tool: The Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) One Health Assessment Tool (OHAT), designed for national-level assessments, can be adapted for community use (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2025). Communities could adapt this by convening a community level intersectoral group to answer each indicator as it applies locally. At the community level, this could involve:

- Stakeholder Workshops engaging local leaders, farmers, health workers, and environmental groups to answer indicator-based questions e.g., Is there a local surveillance system for zoonotic diseases? or Is there a municipal plan for managing agricultural runoff?

- Action Planning: Developing community-specific action plans to address gaps identified in stakeholder workshops, such as improving access to veterinary services or environmental monitoring.

- Baseline Establishment: Post action planning, a tool such as the FAO One Health Assessment Tool (OHAT), can be used to establish a Community level One Health baseline, and then track progress year to year.

3. Common gaps that hinder community One Health

Despite progress in One Health, several gaps hinder effective understanding and implementation at the community level. Assessment and implementation often stumble on the same structural problems:

- Sectoral silos: human, veterinary and environmental data collection and funding streams run independently, making early detection of cross-cutting threats difficult. Siloed systems and approach exist from the national to the community level – from data and detection (separate databases managed by distinct agencies and separate surveillance systems) to response systems (separate rapid response teams, procedures and processes).

- Weak two-way communication: top-down programs that don’t solicit or respond to local knowledge lose legitimacy and miss local sentinel signals.

- Limited multi-disciplinary workforce: CHWs, vets and environmental officers are usually trained separately and lack shared competencies for joint surveillance and response.

- Short-term, reactive financing: funding often arrives after outbreaks rather than supporting continuous prevention, surveillance and community capacity. This lack of stable, integrated funding undermines long-term One Health capacity building thus disallowing systemic integration of One health principles at all levels including the community level.

- Social barriers and mistrust: historical or cultural factors, such as past mismanagement of health crises, can lead to distrust between communities and health organizations. This impedes collaboration and data sharing thus affecting reporting and uptake of control measures.

- Limited Community Engagement: Many One Health initiatives adopt a top-down approach, failing to involve communities as active participants. This misses local expertise and reduces intervention effectiveness. Evidence suggests that bottom-up engagement is critical for success. (Sangong, Saah, & Bain, 2025) Evaluation frameworks for One Health systems consistently identify community engagement gaps as primary barriers to effective surveillance and response. (Mediouni, et al., 2025) As Henley et al. emphasize, frameworks must engage communities particularly rural and marginalized groups who are often most vulnerable. Failure to involve community representatives means missing essential sentinels for early warning. (Henley, Igihozo, & Wotton, 2021) Without community ownership, programs also risk low compliance.

4. Recommendations to Fill Gaps

To overcome these challenges, evidence-based actions are recommended:

- Multisectoral Collaboration:

- Convene a small committee (monthly or quarterly) with community representatives, CHWs, para-veterinarians, environmental officers, and local authorities. Such forums foster regular dialogue and joint planning.

- Implementation steps include scheduling quarterly One Health council meetings, developing shared goals, and creating MOUs for cooperation.

- Joint exercises (like tabletop outbreak drills) can further strengthen interagency coordination.

- Use simple terms of reference and allocate one focal person for coordination.

- Adopt lightweight, shared surveillance tools and integrated data systems:

- Develop interoperable data platforms for human, animal and environmental health.

- At the community level, authorities might adopt simple solutions like shared case-report forms, integrated community-based syndromic surveillance systems that provide alerts, and unified digital dashboard. Standardize a short joint reporting form (paper or mobile) for flagged human, animal or environmental events.

- Even integrating efforts where CHWs, livestock owners and environmental officers enter data into a common community reporting system can dramatically improve surveillance.

- This system will be able to generate early warning alerts, guide deployment of joint RRT for investigation, and guide targeted health messages for sharing with the community.

- Layer workforce training and cross-posting:

- Train community health workers, veterinarians, and environmental officers in One Health competencies.

- Develop local training modules covering zoonotic disease recognition, outbreak detection, infection prevention and hygiene best practices in humans and animal husbandry, judicious antimicrobial use (Chung, 2025) (Ahmed, et al., 2024), community engagement skills and cross-sector communication.

- Communities could partner with institutions/NGOs that provide short modular training on zoonoses and environmental hazards to CHWs and para-veterinarians.

- Supporting cross-training internships or cross-sector attachments (e.g. a CHW spends a day in a veterinary clinic and a para-vet in a health center) can also break down silos early.

- Community engagement:

- Use participatory methods at every stage. This includes running a small workshop where residents rank proposed actions by impact and feasibility (e.g., improved waste disposal, targeted livestock vaccination), co-designing locally appropriate risk communication messages and delivery channels; and involving community members in needs assessments, planning interventions, and evaluating outcomes.

- On the ground, this might translate to regular village health committee meetings, orientation on syndromic surveillance, disaster preparedness planning, community-led response mechanisms, citizen science projects (like community water testing), or youth groups monitoring environmental indicators.

- Training local One Health champions (e.g. respected community leaders) helps disseminate information effectively.

- Build trust through transparency and feedback – Invest in transparent, respectful relationships with communities. This means regular communication in local languages, acknowledging historical grievances, and involving communities in decision-making. Trust-building strategies should draw from successful regional experiences in intersectoral coordination and systematic intervention approaches (Ghosal, et al., 2024) (Taaffe, et al., 2023).

- Use trusted local staff as liaisons; hold open forums to explain health measures; and provide feedback loops so community questions are answered.

- Share assessment findings in public meetings and provide regular updates on actions taken and outcomes.

- Recruit and empower local One Health champions who are respected by residents and can translate technical messages.

- Plan for modest, sustainable funding:

- Rather than relying solely on reactive emergency funds, seek grants and partnerships for One Health capacity building.

- Emphasize cost-effectiveness – Identify low-cost, high-impact investments (basic cold chain for vaccines, simple water testing kits, travel stipends for outreach).

- Explore local partnerships (cooperative societies, agribusinesses) and integrate One Health items into routine municipal budgets.

These recommendations align with global One Health strategies notably the WHO’s Quadripartite plan, which calls for cross-sector capacity building and community engagement. In sum, bridging gaps requires coordinated governance, data harmonization, and genuine partnership with communities.

5. Essential Skills for Community-Level One Health Implementation

Effective community One Health programs depend on a workforce with diverse competencies. Successful programs rely on multifaceted abilities, cultivable via blended training on a small set of practical skills that can be taught and reinforced in short courses. The following skills drawn from community health worker and One Health competency frameworks are particularly important at the local level (Rebekah, et al., 2016) (Covert, 2019) (Core Competencies for Community Healthworkers, 2014):

- Risk communication & community engagement: craft clear, local language messages and handle rumours respectfully.

- Basic surveillance and data handling: record simple indicators, use checklists, and escalate unusual events.

- Practical environmental inspection: recognize signs of water contamination, vector breeding sites, and poor waste management.

- Animal health basics: identify common livestock illness signs, know basic husbandry and vaccination schedules, and advise when to seek a veterinarian.

- Coordination & referral: know whom to call for which problem and how to link human and animal cases for joint follow-up.

- Advocacy & reporting: present concise, evidence-based requests for local resources and track how funds are used.

- Cultural competence: apply interventions that respect local norms and gender roles.

The following table outlines a One Health competency framework defining the skills and their relevance for one health:

| Skill | Description | Relevance to One Health |

|---|---|---|

| Outreach and Communication | Engaging diverse community members through clear, accessible communication of health risks and solutions. | Essential for educating communities on zoonotic risks, environmental hazards, and preventive behaviors. |

| Assessment and Surveillance | Monitoring health indicators across humans, animals, and the environment using tools like citizen science or local surveillance systems. | Enables early detection of outbreaks, such as zoonotic diseases, and environmental health threats. |

| Education and Behavior Change | Promoting healthy behaviors through education, counseling, and community campaigns. | Encourages practices like proper animal husbandry, waste management, or vaccination uptake. |

| Care Coordination | Linking community members with services across human health, veterinary, and environmental sectors. | Facilitates access to integrated health services, improving overall community health outcomes. |

| Advocacy | Representing community needs in policy discussions and securing resources for One Health initiatives. | Ensures local priorities, such as access to veterinary care, are addressed in broader health policies. |

| Cultural Competence | Understanding cultural, social, and linguistic contexts to design acceptable interventions. | Enhances trust and effectiveness of One Health programs, particularly in diverse communities. |

| Technical Skills | Knowledge of zoonotic diseases, environmental health risks, and animal husbandry practices. | Supports integrated interventions, such as monitoring water quality or managing livestock health. |

For the ease of operations, the aforementioned competency framework can further be segregated into Community level (or Field level) skills and Facility level (Primary Healthcare) skills.

TABLE 4A. Field-level One Health Skills required by HCW in Community

| Skill | Competencies / Tasks | Training Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Frontline surveillance & event detection | Recognize/report unusual animal deaths, human illness clusters, vector changes, environmental hazards. Use simple case definitions, short reporting forms, and geo-referencing. | Short practical sessions, role-play “what would you report?”, field walks, participatory mapping. |

| Basic animal-health interventions & biosecurity | Identify livestock disease signs (abortions, high mortality), basic wound care, advise isolation/quarantine, implement on-farm biosecurity (footbaths, manure management), assist vaccination drives; safe animal handling and carcass management. | Hands-on mentoring with para-vets; demo clinics; supervised vaccination days. |

| Environmental hazard detection & rapid testing | Basic water testing (turbidity/test strips), observe sanitation failures, identify vector breeding sites, rapid site assessments after floods/land-use change. | Field demonstrations; pictorial job aids and checklists. |

| Safe sample collection & transport | Correct swab/blood/tissue collection, labelling, cold-chain basics, safe packaging, chain-of-custody completion. | Practical labs with mock sampling, PPE practice, cold-chain exercises. |

| Community risk communication & social listening | Explain risk simply, use trusted messengers, counter rumours respectfully, collect community concerns for planning. | Message-design workshops, radio/megaphone practice, social-listening role play. |

| Rapid field triage & immediate first responses | First aid for people; stabilize injured animals/people pre-referral; rabies post-exposure wound care; identify red flags for transfer. | Basic life-support refreshers, first-aid practicals, scenario drills. |

TABLE 4B. One Health Skills required for HCWs in Primary Healthcare Facilities Clinical

| Skill Area | What it is / Definition | Concrete Competencies & Tasks | Training Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surge triage for human/animal caseloads | Rapid sorting of incoming cases by severity and urgency during sudden increases in caseload (e.g., floods, animal die-offs, suspected zoonotic outbreak). | Use 3-level triage (red=urgent, yellow=urgent-but-stable, green=routine); Simulated surge drills; Separate infectious vs non-infectious streams; use PPE for febrile unknowns; Laminated triage checklists at intake; Clear referral triggers for severe cases; Quick staff rotation drills. | Leadership modules; Briefing/debriefing cycles; Incident command basics; Shift rostering; On-the-job mentorship; Incident log & daily updates. |

| Clinical decision-making under uncertainty | Making timely choices when diagnostic resources are limited and information is incomplete. | Apply structured heuristics: focused history + targeted exam + danger signs; Case-based learning with resource constraints; Use probabilistic reasoning to set priorities; Decision trees & bedside mentoring; Take low-risk, high-benefit default actions (e.g., hydration, isolation). | Ethical decision workshops; Documentation templates. |

| Prioritizing care with incomplete information | Allocating limited resources when demand exceeds capacity. | Apply severity scoring and ethical rules; Document rationale; communicate with patients/families; Tabletop triage exercises. | Documentation templates. |

| Core primary clinical skills for One Health contexts | Ability to manage common zoonotic and primary care presentations. | Recognize/manage zoonoses, bite management & rabies referral; Short modules + rotations; Dehydration management, wound/surgical dressing, maternal/newborn stabilization; Antibiotic prescribing audits; Rational antimicrobial use. | Infection prevention & control (IPC) at facility level. |

| Safe referral and liaison | Ensuring timely, safe, and well-communicated patient transfer. | Referral criteria, transport arrangements, feedback loop from receiving facility. | Referral slip templates; Pathway simulations. |

TABLE 4C. One Health Skills required for HCWs in Primary Healthcare Facilities Non Clinical

| Skill Area | What it is / Definition | Concrete Competencies & Tasks | Training Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Team leadership & management during emergencies | Organizing teams for effective crisis response. | Rapid role allocation; Leadership modules; Briefing/debriefing cycles; Incident command basics; Shift rostering; On-the-job mentorship; Incident log & daily updates. | Incident log & daily updates. |

| Balancing competing needs & real-time ethics | Applying fair and transparent allocation principles during crises. | Use agreed ethical principles; Ethics scenarios; Document decisions; Local ethics checklist; Protect vulnerable groups. | Local ethics checklist. |

| Logistics, supply chain & cold chain management | Ensuring essential supplies are tracked and maintained. | Stock tracking, rotation, cold chain troubleshooting, priority requests. | Stock card exercises; Simulated stockouts. |

| Intersectoral coordination & stakeholder engagement | Collaborating across health, agriculture, and municipal sectors. | Convene multi-sector meetings; Cross-sector tabletop exercises; Maintain contacts; MoU/JIP templates; Document agreements/action points. | MoU/JIP templates; Document agreements/action points. |

| Risk communication, media & community relations | Providing accurate, timely public information and countering misinformation. | Prepare updates, handle media, engage trusted voices. | Media drills; Scripted templates; Social listening training. |

| Mental health & staff welfare | Supporting staff psychological well-being. | Peer support, rotation, psychosocial first aid access. | Psychological first-aid training; Post-event debriefs. |

| Data management, reporting & after-action review | Capturing data and lessons for future improvement. | Maintain records, submit reports, conduct after-action reviews. | One-day data courses; Dashboard templates; AAR checklists. |

Conclusion

A One Health approach will only succeed if it starts at the community level. Understanding specific community needs from local disease ecology to social drivers of risk is the crucial first step. By combining quantitative surveillance with qualitative dialogue and participatory planning, communities can identify their highest priorities and craft context-appropriate solutions. Closing the gaps between sectors requires deliberate actions: creating cross-sector partnerships, integrating data systems, and training a One Health savvy workforce. Sustained funding and trust-building are essential to make these changes durable. Equipping local workers with communication, surveillance, and cultural competencies ensures that policies translate into practice.

This roadmap aims to guide policymakers and program managers in developing countries (and beyond) to operationalize One Health on the ground. It draws on global frameworks and practical examples to show how communities can move from concept to action. In an era of emerging zoonoses, antimicrobial resistance and climate-linked health threats, empowering communities with a One Health roadmap is vital to achieving healthier, more resilient societies.

About the Author

Dr. Nochiketa Mohanty is a medical and public health professional holding MBBS degree from V.S.S. Medical College, Sambalpur with MPH and MBA degrees from University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA. With over 20 years of public health experience and a proven track record of success, he has designed and implemented innovative solutions to tackle critical challenges in TB, HIV/AIDS, Reproductive Health, Women’s Cancer, COVID Response, Pandemic preparedness and Global Health security through various placements at National, Regional and State levels.

References:

- Ahmed S, Hussein S, Qurbani K, Ibrahim R, Saber A, Mahmood K, Mohamed M. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. J Med Surg Public Health. 2024;2:100081. doi:10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100081

- Bayisenge U, Ripp K, Bekele A, Henley P. Why and how a university in Rwanda is training its medical students in One Health. Commun Med. 2022;2(1): 153. doi:10.1038/s43856-022-00218-0

- Behravesh CB, Charron DF, Liew A, Becerra NC, Machalaba C, Hayman DT, Sa. An integrated inventory of One Health tools: Mapping and analysis of globally available tools to advance One Health. CABI One Health. 2024;3(1). doi:10.1079/cabionehealth.2024.0017

- Berrian AM, Smith MH, van Rooyen J, Martínez-López B, Plank MN, Smith WA, Conrad PA. A community-based One Health education program for disease risk mitigation at the human-animal interface. One Health. 2017;5:9-20. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2017.11.002

- Buregyeya E, Atusingwize E, Nsamba P, Musoke D, Naigaga I, Kabasa JD, Bazeyo W. Operationalizing the One Health Approach in Uganda: Challenges and Opportunities. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020; 10(4):250-257. doi:10.2991/jegh.k.200825.001

- Chung PY. One Health strategies in combating antimicrobial resistance: a Southeast Asian perspective. J Glob Health. 2025;15:03025. doi:10.7189/jogh.15.03025

- Covert HA. Core competencies and a workforce framework for community health workers: A model for advancing the profession. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(2):320-327. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304737

- Musoke D, Ndejjo R. The role of environmental health in One Health: A Uganda perspective. One Health. 2016;2:157-160. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2016.10.003

- Massachusetts Department of Health. Core Competencies for Community Health Workers. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Published May 13, 2014. Accessed from: https://www.mass.gov/info-details/core-competencies-for-community-health-workers

- Desvars-Larrive A, Vogl AE, Puspitarani GA, Yang L, Joachim A, Käsbohrer A. A One Health framework for exploring zoonotic interactions demonstrated through a case study. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):5650. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-49967-7

- Di Bari C, Venkateswaran N, Fastl C, Gabriël S, Grace D, Havelaar AH, Devleesschauwer B. The global burden of neglected zoonotic diseases: Current state of evidence. One Health. 2023;17:100595. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100595

- Food and Agriculture Organization. One Health Assessment Tool. FAO; 2025. Accessed from: https://www.fao.org/one-health/resources/one-health-assessment-tool/en

- Ghosal S, Pradhan R, Singh S, Velayudhan A, Kerketta S, Parai D, Pati S. One Health intervention for the control and elimination of scrub typhus, anthrax, and brucellosis in Southeast Asia: a systematic review. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2024;30:100503. doi:10.1016/j.lansea.2024.100503

- Guenin MJ, Nys HM, Peyre M, Loire E, Thongyuan S, Diallo A, Goutard FL. A participatory epidemiological and One Health approach to explore the community’s capacity to detect emerging zoonoses and surveillance network opportunities in the forest region of Guinea. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(7):e0010462. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0010462

- Hassan OA, Balogh KD, Winkler AS. One Health early warning and response system for zoonotic diseases outbreaks: Emphasis on the involvement of grassroots actors. Vet Med Sci. 2023;9(4):1881-1889. doi:10.1002/vms3.1135

- Washington State Department of Health. One Health Needs Assessment Report. Washington State Department of Health; 2023. Accessed from: https://doh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2023-09/420-524-OHNAReport.pdf

- Henley P, Igihozo G, Wotton L. One Health approaches require community engagement, education, and international collaborations a lesson from Rwanda. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):947-948. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01350-5

- McEwen SA, Collignon PJ. Antimicrobial resistance: a One Health perspective. Microbiol Spectr. 2018;6(2). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0009-2017

- Mediouni S, Ndione C, Parmley EJ, Poder TG, Carabin H, Aenishaenslin C. Systematic review on evaluation tools applicable to One Health surveillance systems: A call for adapted methodology. One Health. 2025;20:100995. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2025.100995

- Milazzo A, Liu J, Multani P, Steele S, Hoon E, Chaber AL. One Health implementation: A systematic scoping review using the Quadripartite One Health Joint Plan of Action. One Health. 2025;20:101008. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2025.101008

- Nguyen-Viet H, Lâm S, Alonso S, Unger F, Moodley A, Bett B, Grace D. Insights and future directions: Applying the One Health approach in international agricultural research for development to address food systems challenges. One Health. 2025;20:101007. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2025.101007

- Ravaghi H, Guisset AL, Elfeky S, Nasir N, Khani S, Ahmadnezhad E, Abdi Z. A scoping review of community health needs and assets assessment: concepts, rationale, tools and uses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):44. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08983-3

- Rebekah F, William H, Kira C, Debra O, Mary L, Linda V, Carol R. One Health core competency domains. Front Public Health. 2016;4:192. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00192

- Samhouri D, Mahrous H, Saidouni A, El Kholy A, Ghazy RM, Sadek M, Malkawi M. Review on progress, challenges, and recommendations for implementing the One Health approach in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. One Health. 2025;20:101057. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2025.101057

- Sangong S, Saah FI, Bain LE. Effective community engagement in One Health research in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. One Health Outlook. 2025;7(1):4. doi:10.1186/s42522-024-00126-4

- Singh S, Sharma P, Pal N, Sarma DK, Tiwari R, Kumar M. Holistic One Health surveillance framework: synergizing environmental, animal, and human determinants for enhanced infectious disease management. ACS Infect Dis. 2024;10(3):808-826. doi:10.1021/acsinfecdis.3c00625

- Taaffe J, Sharma R, Parthiban AB, Singh J, Kaur P, Singh BB, Parekh FK. One Health activities to reinforce intersectoral coordination at local levels in India. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1041447. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1041447

- Varela K, Goryoka G, Suwandono A, Mahero M, Valeri L, Pelican K, Salyer SJ. One Health zoonotic disease prioritization and systems mapping: An integration of two One Health tools. Zoonoses Public Health. 2022;146-159. doi:10.1111/zph.13015

- Vesterinen HM, Dutcher TV, Errecaborde KM, Mahero MW, Macy KW, Prasarnphanich OO, Valeri L. Strengthening multi-sectoral collaboration on critical health issues: One Health Systems Mapping and Analysis Resource Toolkit (OH-SMART) for operationalizing One Health. PLoS One. 2019;14:1-16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219197

- World Health Organization. One Health. WHO; 2024. Accessed from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health

- WHO, FAO, WOAH, UNEP. One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022-2026). WHO; 2022. Accessed October 14, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240059139

- Yang W, Park J, Cho M, Lee C, Lee J, Lee C. Environmental health surveillance system for a population using advanced exposure assessment. Toxics. 2020;8(3):74. doi:10.3390/toxics8030074

- Yasobant S, Lekha KS, Saxena D. Risk assessment tools from the One Health perspective: a narrative review. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2024;17:955-972. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S436385