Aerobic Capacity’s Role in Breast Tumor Microenvironment

Transcriptional Signatures Connecting Inherent Aerobic Capacity to the Breast Tumor Microenvironment in Rats: Implications for Precision Oncology

Vanessa K. Fitzgerald1, Tymofiy Lutsiv1,2 and Henry J. Thompson1

- Cancer Prevention Laboratory, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA;

- Cell and Molecular Biology Program, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA; *[email protected]

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 October 2025

CITATION: Fitzgerald, VK., Lutsiv, T., and Thompson, HJ., 2025. Transcriptional Signatures Connecting Inherent Aerobic Capacity to the Breast Tumor Microenvironment in Rats: Implications for Precision Oncology. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(10). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i10.7043

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i10.7043

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Aerobic capacity, which is synonymous with the term cardiorespiratory fitness, is a strong inverse predictor of breast cancer mortality, yet the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. In this study, RNA sequence data were used to interrogate the tumor microenvironment for potential etiological clues in a rodent model for breast cancer, widely regarded to have similar histogenesis and pathogenesis as the human disease, including about 70 percent of the tumors being ovarian hormone-responsive mammary carcinomas. What was novel about our approach is that tumor microenvironment gene expression profiles were contrasted between genetically distinct sedentary rats selectively bred to have low vs. high inherent aerobic capacity. Inherent aerobic capacity is generally overlooked as a variable in human populations, yet the observed range exceeds three-fold. RNA sequence analysis was performed on mammary carcinomas and adjacent uninvolved mammary glands, i.e., the tumor microenvironment. Investigation of effects on canonical signaling pathways, upstream regulators, and downstream effectors identified differentially expressed transcriptional signatures within the renin-angiotensin system, interferon gamma, and nitric oxide signaling pathways, distinguishing between low or high inherent aerobic capacity in the tumor microenvironment. Within these pathways, master upstream regulators: interferon gamma, interleukin-1 beta, tumor necrosis factor, and angiotensinogen emerged as part of a complex network reflecting inherent aerobic capacity-related differences, which were accompanied by differences in immune cell populations present within the tumor microenvironment. The data support the potential value of inherent aerobic capacity phenotyping in the development of precision approaches to breast cancer treatment.

Keywords

inherent aerobic capacity; breast cancer; transcriptional signatures; intracellular signaling; biomarkers; renin-angiotensin system; interferon gamma; mammary gland; tumor microenvironment; nitric oxide signaling.

1. Introduction

A physically active lifestyle is associated with a lower risk for breast cancer. As a result of higher levels of physical activity, frequently achieved through a subset of physical activity behaviors known as exercise, aerobic capacity is increased. Aerobic capacity, also known as cardiorespiratory fitness, embodies an objective and reproducible measure of the functional consequences of physical activity habits and reflects the amount of energy an individual can generate and use on a sustained basis. It has been hypothesized as a potential mechanism underlying the physical activity-cancer linkage.

Aerobic capacity has two components: inherent, the genetic component with which an individual is born, and acquired, the amount of capacity that is gained via a physically active lifestyle and/or exercise training. All-cause mortality and breast cancer-related mortality are inversely associated with aerobic capacity. Inherent aerobic capacity (IAC), estimated in sedentary individuals by measuring VO2max, has been shown to vary by more than 3-fold in population studies, a factor that undoubtedly contributes to differences in mortality, yet the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer newly diagnosed in women annually, accounting for 32% of cases in the US. In 2025, approximately 316,950 women will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, with 59,080 new cases of ductal carcinoma in situ, and around 42,170 women are estimated to die from breast cancer in 2025.

Higher levels of regular physical activity protect from developing breast cancer. In a prospective study on the association between aerobic capacity and risk of death from breast cancer in over 14,000 women, age-adjusted breast cancer mortality rates were 2.4-fold lower in the high vs. the low aerobic capacity group. In another prospective cohort study, high aerobic capacity was associated with a 24% lower risk of breast cancer among overweight postmenopausal women. Nevertheless, chemotherapy has been shown to reduce the aerobic capacity of breast cancer patients concomitant with increased symptom burden, highlighting the importance of inherent levels of aerobic capacity which are unaffected by lifestyle or cancer therapy.

In an effort to disentangle the effects of physical activity per se from the effects of differences in aerobic capacity, a program of selective breeding was initiated in an outbred strain of rats (N:NIH). Rats were selectively bred over many generations for inherent running capacity on a treadmill, resulting in two distinct IAC populations, high IAC (HIAC) and low IAC (LIAC). Using these HIAC and LIAC models and a well-documented approach to mammary cancer induction, we have previously reported potent inhibition of carcinogenesis in HIAC compared to LIAC rats. Even though both groups of animals were sedentary, HIAC was highly protective against cancer. Nonetheless, tumors did occur in both LIAC and HIAC, providing an opportunity to investigate the effects of IAC on the tumor microenvironment (TME) as a potential origin of the IAC-related observed differences in breast cancer mortality.

In general, aerobic capacity is a trait thought to reside in cardiac and skeletal muscle, with most research focusing on these tissues. Analysis of skeletal muscle from individuals differing in IAC has shown that differences are due to minor effects involving seemingly unrelated genes, and key regulators have yet to be identified. In this study, the goal was to use RNA sequencing technology to identify transcriptional signatures whose differential regulation between HIAC and LIAC occurred in mammary carcinomas and their adjacent uninvolved mammary gland, which is operationally defined as the TME. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the mammary TME at the transcriptome level in these distinct populations of IAC rats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 OVERVIEW

The RNA evaluated in this study was isolated from tissue frozen in liquid nitrogen from a previously published investigation. No extraction or analysis of RNA from that investigation has previously been reported, and accordingly, those methods are provided in detail.

2.2. STUDY DESIGN

Breeding pairs of HIACs and LIACs from generation 29 of selection (n = 8/cohort) were obtained from the Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Michigan. Female pups weaned from dams at 21 days of age were assigned to three groups: one with offspring from N:NIH breeding pairs, one with offspring from LIAC breeding pairs, and the third with offspring from HIAC breeding pairs. Rats remained sedentary for the entire study, i.e., they had regular cage activity within the group housing setting (3 rats/cage). Animals were maintained in solid-bottomed polycarbonate cages and fed a standard laboratory diet (Harlan 2918 Teklad Lab Animal Diet, Envigo, Indianapolis, IN, USA) ad libitum. Rooms were maintained at 22 ± 1 °C with 50% relative humidity and a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. At 21 days of age, female rats were injected intraperitoneally with 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea (MNU, Ash Stevens, Detroit, MI, USA), as previously described. At study termination, overnight fasted animals were euthanized between 8 a.m. and 11 a.m. via inhalation of gaseous carbon dioxide. All detectable mammary gland pathologies were histologically classified. Excised pieces of mammary tumors (size permitting) and mammary gland were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted according to the committee guidelines at Colorado State University.

2.3. RNA ISOLATION

Individual frozen tissue samples were placed in liquid nitrogen filled ceramic mortars and ground to a fine powder using a ceramic pestle. The ground tissue powder was quickly placed in a precooled 2 mL RNase-free microfuge tube and frozen at -70°C prior to isolation. Samples were removed from the -70°C freezer and immediately placed on ice. RNA samples were isolated using reagents from the RNeasy mini-kit (Qiagen, Inc., Germantown, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Mammary gland samples were isolated using Qiazol (Qiagen, Inc.) and the chloroform extraction method, followed by RNA isolation of the aqueous layer using the RNeasy mini kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Tumor samples were isolated using the RNeasy mini-kit (Qiagen, Inc.) with the addition of a proteinase K digestion step for 10 min at 55 °C between the lysis buffer and ethanol steps.

2.4 RNASEQ ANALYSIS

Isolated RNA concentration and purity (260/280 and 260/230 ratios) was checked via NanoDrop (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA integrity was determined using an Experion instrument (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Samples were diluted to a concentration of 4 ng/µL in 50 µL of RNase-free water and shipped under dry ice to the Genomics and Microarray Core at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Center (Aurora, CO, USA) for library preparation (Nugen Universal mRNA kit, Tecan Genomics, Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA) and RNA paired end (2×150) sequencing using a NovaSEQ 6000 sequencer (Illumina, Inc. San Diego, CA, USA). Demultiplexed raw fastq data files were uploaded to the RMACC Summit super-computer at the University of Colorado (Boulder, CO, USA). A singularity container comprised of the following programs was used in conjunction with various scripts to process sequencing data: fastp (sequence trimming and quality control); hisat2 (genome alignment); and featurecounts (tabulating the number of reads per gene). Hisat2 indices were constructed using the Rattus norvegicus (Rnor_6.0) gene annotation chromosome fasta files and corresponding gtf file. Feature counts from individual samples were merged into a single tab-delimited text file using an R script. The merged feature counts tab-delimited text file containing Ensembl IDs was imported into the CLC Genomics Workbench v20 (Qiagen Digital Insights, Redwood City, CA, USA). Samples were grouped by experiment conditions, and data were normalized and log-transformed. Differential gene expression was determined using the ‘ExactTest’ for two-group comparisons developed by Robinson and Smyth and incorporated in the EdgeR Bioconductor package. All comparisons were FDR-corrected using Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, and the resulting data were exported to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (QIAGEN IPA, Qiagen Digital Insights) for further analysis.

2.5. WESTERN BLOTING AND NANO-CAPILLARY ELECTROPHORESIS

Mammary gland and tumor tissue lysate were prepared and Western blotted as previously reported. Briefly, tissue was homogenized in lysis buffer [40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1% Triton X-100, 0.25 M sucrose, 3 mM EGTA, 3 mM EDTA, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenyl-methylsulfonyl fluoride, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA)]. The lysates were centrifuged at 7500 x g for 10 min at 4ºC and supernatant fractions collected and stored at -80 °C. Supernatant protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad). Western blotting was performed as described previously. Briefly, 40 µg of protein lysate per sample was subjected to 8–16% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gradient gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) after being denatured by boiling with SDS sample buffer [63 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 50 mM DTT, and 0.01% bromophenol blue] for 5 min. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The amounts of target proteins were determined using specific primary antibodies, followed by treatment with the appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and visualized by LumiGLO reagent western blotting detection system. The chemiluminescence signal was captured using a ChemiDoc densitometer (Bio-Rad). Nanocapillary electrophoresis was performed using the Jess instrument (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA, USA) as previously described with the following changes: final concentration of the protein lysates was 0.2 mg/ml, and each primary antibody was incubated for 120 min. The primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) was used: rabbit anti-PPARγ (cat. SC-7196). Data were normalized by dividing the target protein peak area by the corrected total protein area of the sample within each capillary.

2.6. PCR-RT2 PROFILER ASSAYS

Tumor RNA from 4 LIAC and 4 HIAC animals was run on Qiagen RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays specific to 84 rat nuclear receptors and coregulators (PARN-056Y) (Qiagen, Inc.). The arrays are pathway-focused panels of laboratory-verified qPCR assays, with integrated, patented controls. Each biological replicate was run on its own RT2 Profiler PCR Array. Initially, the RT2 First Strand Kit was used to synthesize cDNA using 0.5 μg RNA and then combined with 2X RT2 SYBR Green Mastermix according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each well of the PCR array was loaded with 25uL cDNA/SYBR green mix. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on an iCycler (Bio-Rad) under the following conditions: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. Fluorescent products were detected at the last step of each cycle. Ct values were exported and uploaded for analysis using the GeneGlobe Data Analysis Center (Qiagen Digital Insights). Fold change and p-values were exported and uploaded to IPA for analysis.

2.7. INGENUITY PATHWAY ANALYSIS (IPA)

Gene Expression Core Analysis was performed in IPA version 76765844 (Qiagen Digital Insights) for each tissue, comparing HIAC to LIAC differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Briefly, identified DEGs and their expression differences were cross-referenced with the studies from the IPA internal Knowledge Database and mapped to the reported signaling pathways based on similar expression patterns. Intrinsic IPA algorithms calculate the overlap ratio (i.e., a ratio of the number of observed genes from our dataset divided by the total number of genes from the IPA Knowledge Database that map to the particular pathway); the z-score to infer potential activation or inhibition of the pathway (if its values exceed the absolute value of 2), as well as p-value of the overlap to determine significance (our threshold was -logp-value > 1). Pathways with the significant p-value of overlap but insignificant and/or unable to calculate z-scores were included in the data analysis due to valuable information on DEGs patterns. Quality-filtering encompassed a p-value cutoff of 0.05 and log2 fold change of 0.58, indicating gene expression significance. When applicable, a |z|-score > 2 was the cutoff for a significantly activated state of pathway/regulator, while |z|-score < -2 was indicative of statistical inhibition. The RNA-Seq dataset used in this work can be found in GEO under the accession number GSE190840.

2.8. ORTHOGONAL PROJECTIONS TO LATENT STRUCTURES FOR DISCRIMINANT ANALYSIS (OPLS-DA)

Our approach has been previously reported. Briefly, orthogonal projections to latent structures for discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) is a supervised, class-based method where class membership is assigned to samples and used to elicit maximum data separation. Visualization of OPLS-DA Scatter plots of the first two score vectors for each model were drawn based on Hotelling’s multivariate T2, to identify outliers that might bias the results of OPLS-DA. For OPLS-DA, class separation is shown as the first predictive score plotted against the first orthogonal score to visualize the within- and between-class variability associated with the first principal component. S-plots were constructed to identify influential genes in the separation of HIAC from LIAC. The model’s ability to classify observations into defined classes is reflected in the misclassification rates for each model, where IAC status was determined by the modeled probability of a single observation belonging to a particular class. We also constructed S-plots based on the first principal component, showing reliability (modeled correlation) plotted against feature magnitude (loadings or modeled covariance). If genes have variation in correlation and covariance between classes, this plot will assume an S-shape (giving the plot its name), with heavily influential features separating from other features at the upper right and lower left tails of the feature cloud within the model space. All analyses were done using SIMCA-P+ v.12.0.1 (Umetrics, Umea, Sweden).

3. Results

Female rats, selectively bred for high (HIAC) and low (LIAC) inherent aerobic capacity (IAC), were exposed to a chemical carcinogen (1-methyl-1-nitrosurea, MNU) via intraperitoneal injection in order to induce the development of mammary adenocarcinoma. High IAC animals exhibited prolonged cancer latency (Mantel hazard ratio = 4.01 (95% confidence interval = 2.02–7.93; p = 4 × 10-4) compared with LIAC counterparts, as well as significant reduction in the cancer incidence (14.0% vs. 47.3%; p < 0.001) and multiplicity (0.18 vs. 0.85 cancers per rat; p < 0.0001). More information on the carcinogenic response can be found in our previous reports, indicating that high levels of IAC are protective against mammary carcinogenesis. Despite being protected against carcinogenesis, HIAC rats still developed some mammary carcinoma, and thus, provided an opportunity to investigate the impact of differences in inherent aerobic capacity on the TME.

Total RNA was extracted from mammary carcinoma and the uninvolved adjacent mammary gland of HIAC and LIAC rats, and RNA-Seq analysis was performed to infer functional differences in their transcriptomes. We detected 18,479 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in HIAC tumors compared to LIAC tumors, out of which 1474 (561 were upregulated and 913 were downregulated) met our processing and quality-filtering criteria and were ready for subsequent analysis (Supplementary Table S1). We detected 1859 analysis-ready DEGs (800 were upregulated and 1059 were downregulated, Supplementary Table S1) out of 18,575 in HIAC compared to LIAC mammary gland. As described in subsequent sections, these DEGs were subjected to the Core Expression Analysis in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) to infer the canonical pathways in which they potentially participate.

3.1. MOLECULAR SUBTYPES OF BREAST CANCER

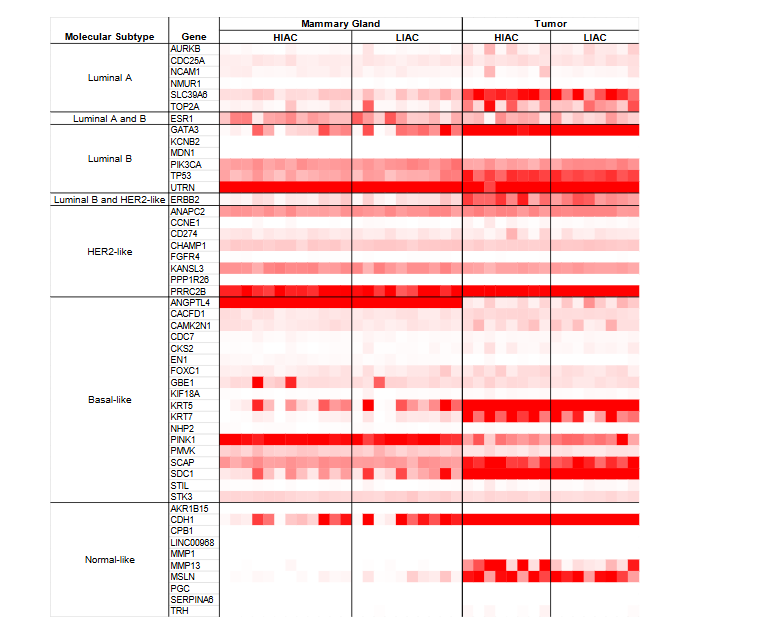

Based on RNAseq transcription patterns, molecular subtypes of breast cancer were assessed. The expression of genes known as hallmarks for each molecular subtype is shown in Figure 1. Chemically induced mammary tumors are generally considered to be hormone responsive but are known to harbor a heterogeneous mixture of cellular components. Strong expression of genes associated with luminal A and B breast cancers was observed in counts per million reads (CPM) expression data. High IAC tumors showed elevated expression of ERBB2 (HER2), consistent with Luminal B or HER2-like molecular subtypes, and MMP13, indicating Normal-like breast cancer. High IAC tumors also had elevated expression of ESR1 and SLC39A6 compared to LIAC tumors, suggesting these tumors group with the Luminal A molecular subtype.

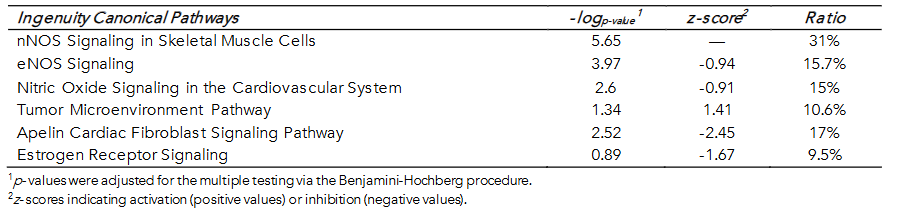

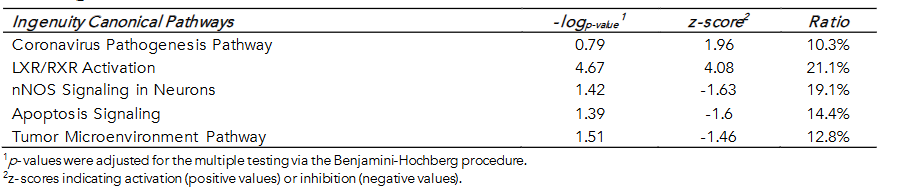

3.2. INHERENT AEROBIC CAPACITY-ASSOCIATED DIFFERENCES IN MAMMARY TUMORS IMPLICATE NITRIC OXIDE SYNTHASE AND THE RENIN-ANGIOTENSIN SYSTEM

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) within tumor samples of HIAC vs. LIAC animals, significantly mapped with 94 canonical pathways from the IPA Database (corrected -logp-value > 1; Supplementary Table S2). Table 1 contains the top canonical pathways. Nitric oxide (NO) regulation mapped to several statistically significant NOS-associated pathways having a strong overlap ratio with tumor DEGs but not a significant z-score. Inducible NO synthase (NOS2 or iNOS) showed higher expression in HIAC tumors than LIAC (log ratio = 4.054, p-value < 0.001). Inducible NOS2 is involved in a reduced immune response and mapped to several significant pathways in HIAC tumors, including the Tumor Microenvironment Pathway, which was activated in HIAC. Similar to iNOS, the endothelial NO synthase (NOS3 or eNOS) Signaling pathway had a high overlap ratio. Although NOS3 was not detected in the RNA-seq data, lysates blotted for eNOS expression showed higher expression in HIAC tumors than LIAC (log2 fold change 3.39, p-value < 0.001, data not shown).

Another pathway with a high overlap ratio was Apelin Cardiac Fibroblast Signaling Pathway (Table 1) due to low expression of its receptor APLNR (expression log ratio = -0.96, p-value < 0.01), which IPA predicts would lead to the development of fibrosis. Furthermore, within this pathway, HIAC tumors also exhibited higher expression of AGTR1 (expression log ratio = 0.83, p-value = 0.037) and downstream SERPINE1 (expression log ratio = 1.23, p-value = 0.012) relative to LIAC tumors, suggesting involvement in the canonical RAS pathway. Expression of estrogen receptors in HIAC tumors was inhibited (ESR1/2, expression log ratio < -2, p-value < 0.05), consistent with the predicted reduction in Estrogen Receptor Signaling. The full list of canonical pathways differentially activated in HIAC vs. LIAC can be found in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Table S2).

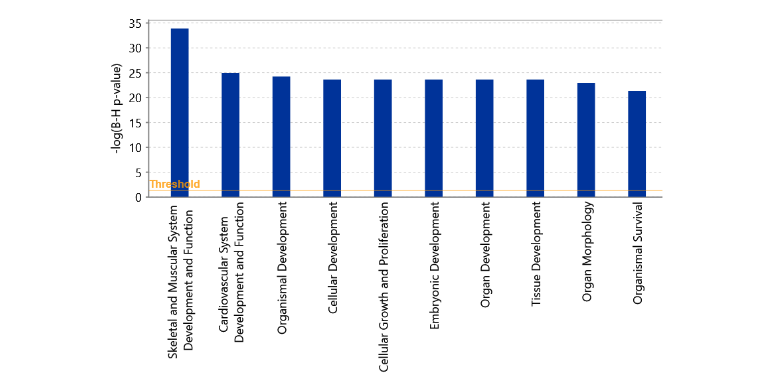

Differentially expressed genes in tumors of HIAC vs. LIAC rats were also assessed for the biological functions to which they mapped in the IPA Core Analysis, with a specific focus on the Molecular and Cellular Functions, as well as Physiological System Development and Function. Figure 2 illustrates the top 10 biological functions that were the most significantly enriched in the HIAC tumors compared to their LIAC counterparts. Tumor DEGs overlapped with the Skeletal and Muscular System Development and Function. Considering that originally aerobic capacity has been studied as a function of skeletal muscle, this indicated that inherent aerobic capacity differences translate to the tumor tissue.

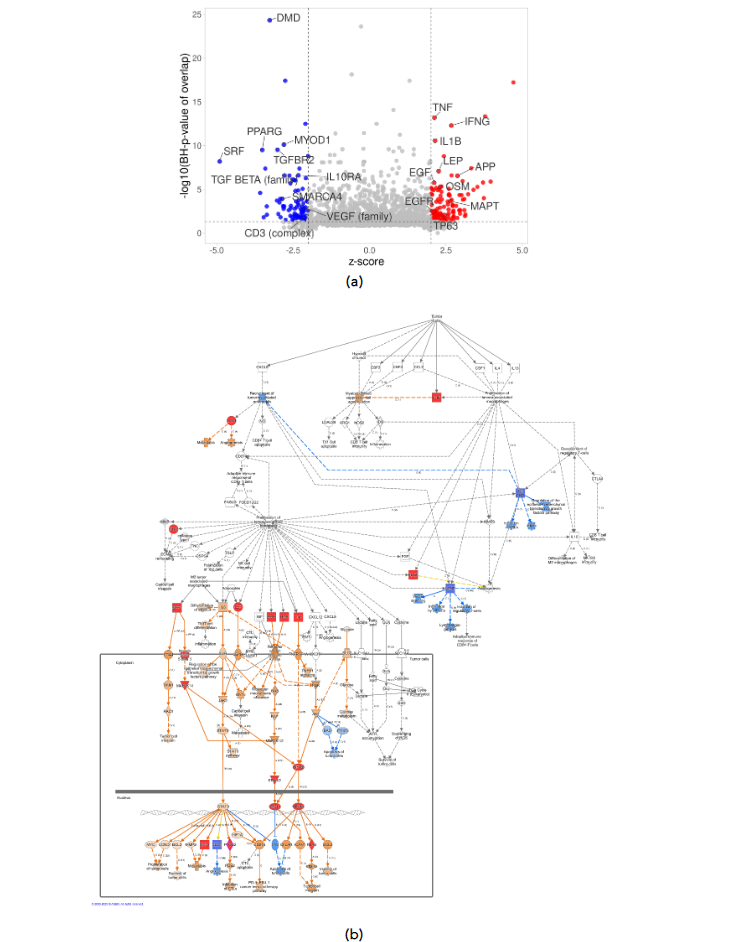

Upstream regulator analysis revealed potential activation or inhibition of molecules upstream of signaling pathways based on the patterns of expression. Among the top upstream regulators, activation of IFNG and TNF was predicted, as well as inhibition of PPARG and VEGF family in HIAC relative to LIAC tumors. Additionally, upstream regulator analysis revealed activation of SPP1, PTGS2, PLAU, PDGF (complex), NFKB1-RELA (complex), MAPK3K14, ITGA5, HGF, FN1, ERK1/2 (family), and AP1 (complex), molecules that are involved in the Tumor Microenvironment Pathway according to the IPA Ingenuity Database. Collectively, the upstream regulator data indicate that IAC status exerted distinct effects on the TME. The complete list of upstream regulators can be found in Supplementary Table S3.

Figure 3. Upstream regulator analysis of expression patterns in HIAC vs. LIAC tumors. (a) Volcano plot shows top 25 molecules with the highest number of downstream DEGs; (b) IPA Tumor Microenvironment Pathway: activated (red) and inhibited (blue) upstream regulators, arrows indicate end-point activation (orange), inhibition (blue), or contradicting (yellow) relationships.

Next, total RNA isolated from the tumor obtained from HIAC and LIAC was assessed for gene expression using RT² Profiler PCR Arrays as described in the Materials and Methods. The RT² Profiler module focused on 84 genes involved in upstream nuclear regulation. The LIAC tumors were used as the reference group. The relative gene expression from the RT² Profiler is summarized and shows validation of RNAseq CPM expression data by a similar hierarchical clustering of the same genes (Supplementary Table S4 and Figure S1). However, only two transcripts from the RT² Profiler PCR Arrays had statistically significant differential expression based on IAC: androgen receptor (AR) (fold change -2.98, p-value 0.043) and NR2F1 (fold change -3.86, p-value 0.046), which were both inhibited in HIAC tumors. Along with AR and NR2F1, many of these transcripts are important regulators of breast carcinogenesis (i.e., ESR2 and PPARγ) and show downregulation in HIAC tumors compared to LIAC tumors, although not with a statistically relevant p-value below 0.05, suggesting different signaling of tumor development dependent on IAC status.

3.3. INHERENT AEROBIC CAPACITY-DRIVEN DIFFERENCES IN THE UNINVOLVED MAMMARY GLAND IN THE MAMMARY TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT IMPLICATE NITRIC OXIDE SYNTHASE, THE RENIN-ANGIOTENSIN SYSTEM, AND INTERFERON-GAMMA SIGNALING

To further understand the differences that IAC may exert on the TME, we compared the transcriptomes of the adjacent uninvolved mammary gland tissue of HIAC to LIAC rats, given that the tissue’s proximity to mammary carcinoma is part of the TME. Differences in the signaling pathways of the mammary tissues based on observed DEGs were reflective of previously mentioned patterns determined in their adjacent tumors (Table 2, Supplementary Table S2). Ingenuity pathway analysis mapped HIAC DEGs to NO-related pathways with statistical significance (nNOS Signaling in Neurons and Skeletal Muscle Cells; Supplementary Table S2). The expression level of NOS1 was elevated in HIAC mammary gland compared to LIAC counterparts (expression log ratio = 1.036, p-value < 0.01), unlike their tumors. NOS2 was not detected among DEGs of HIAC vs. LIAC mammary glands, but among the elements of previously mentioned pathways, VEGFA had an expression log ratio = 0.695, p-value = 0.006. AKT and ERK1/2 signaling cascades were also downregulated in the mammary tissue of HIAC.

Among pathways that differed from the comparison of their tumor counterparts, the Tumor Microenvironment Pathway was downregulated in HIAC mammary gland (z-score -1.46), as was Apoptosis Signaling (z-score -1.6). The highest activation z-score in the mammary gland of HIAC rats was in LXR/RXR Signaling (z-score 4.08), where this pathway showed downregulation in the tumor (z-score = -1.73). Retinoid X receptors (RXRs) mediate transcription of genes involved in lipid metabolism, inflammation, apolipoprotein, xenobiotic transporters, and cholesterol to bile acid metabolism. Among the molecules constituting activation of this pathway is AGT (expression log ratio = 1.184, p-value = 0.001) and the downstream target of its receptor—SERPINA1 (expression log ratio = 2.867, p-value < 0.001). The latter affects many of the common targets with RXR signaling, including the immune response agents. Angiotensinogen (AGT) is also part of the Coronavirus Pathogenesis Pathway, activated in the HIAC mammary gland, and the RAS Pathway. The IPA algorithm predicted that the HIAC mammary gland downregulates additional signaling nodes. TNF-mediated proinflammatory and adaptive immune responses, as well as activation and migration of dendritic cells, were downregulated (TNF, log ratio = -2.073, p-value < 0.01). IFN-γ signaling was also predicted to be downregulated due to lower expression of CAMKII (log ratio < -2, p-value < 0.05), TNF, and FAS (FASLG, log ratio = -1.573, p-value < 0.05) in the HIAC mammary tissue.

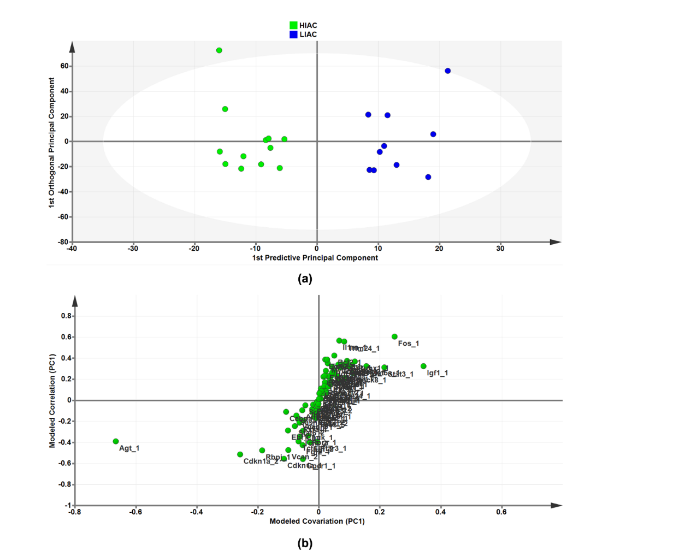

As an independent approach from the use of the IPA bioinformatics platform for identification of transcriptional signatures, we took the list of significantly affected upstream regulators and subjected the CPM mapped expression data from each animal’s tissues to orthogonal projections to latent structures for discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), a widely used machine learning tool. To determine contributing sources of variation, the scatterplot represents supervised analysis of the 2-class OPLS-DA model, which rotates the model plane to maximize separation due to class assignment. The resulting score plots show separation by IAC (Figure 4a). The accompanying S-plot was constructed by plotting modeled correlation in the first predictive principal component against modeled correlation from the first predictive component to identify the upstream regulators that contribute most to the separation between HIAC and LIAC mammary glands (Figure 4b). Of particular interest was the identification of AGT, a regulator of the Renin-Angiotensin System (RAS), as the most influential transcript in distinguishing the transcriptome obtained from HIAC vs. LIAC mammary glands. While probing for evidence of downstream effects of RAS in the mammary gland from HIAC relative to LIAC rats, lysates were blotted for proteins within the RAS pathway reported to be reduced either by inhibition of canonical RAS signaling in the breast or via exercise training that suppresses canonical RAS. As shown in the Supplementary Figure S2, there are significant reductions in levels of cAMP, activated PKA, SRC, STAT3, and MAPK (ERK2, p38) and an increase in SIRT1 in HIAC vs. LIAC. Additionally, OPLS-DA data for mammary carcinoma are shown in Supplementary Materials.

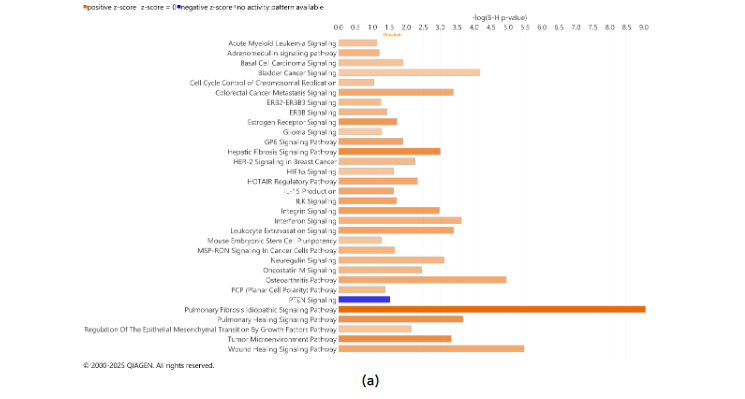

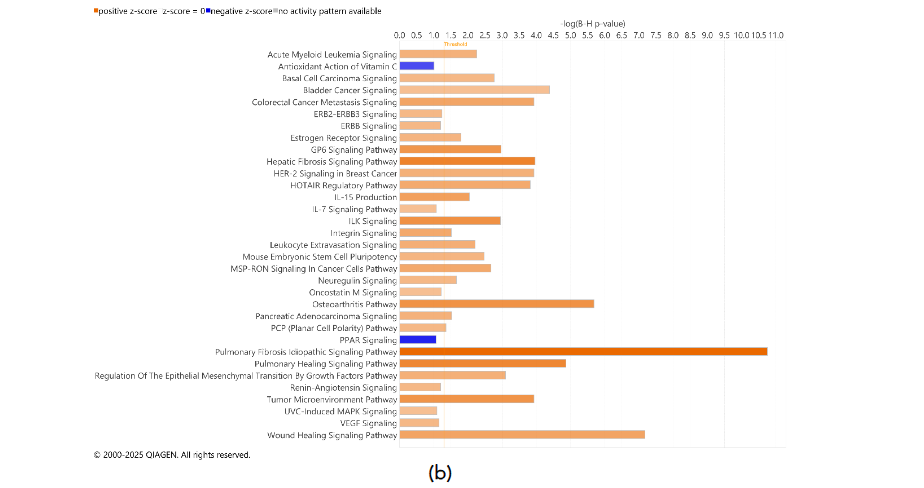

3.4. INTERACTIONS WITHIN THE TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT COMPARTMENTS DISTINGUISHED BY INHERENT AEROBIC CAPACITY

Tumors DEGs were contrasted to DEGs in adjacent uninvolved mammary glands in each cohort of animals with high and low IAC. Figure 5 contains the most significant canonical pathways revealed by the IPA analysis of gene expression. In both HIAC and LIAC mammary glands, there was a significant upregulation of many oncogenic pathways, among which fibrotic ones had the highest z-scores. Patterns of gene expression in both HIAC and LIAC also mapped to many carcinogenic pathways, namely activation of acute myeloid leukemia, basal cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer metastasis, HER-2 signaling in breast cancer, MSP-RON signaling in cancer cells, regulation of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition by growth factors, and the TME canonical pathways. Thus, the majority of canonical pathways that were mapped indicated that carcinogen treatment induced functionally common gene expression patterns. However, some pathways reaching significant overlaps with expression patterns were different in the HIAC compared with the LIAC animals. Tumors of HIAC animals showed upregulation of adrenomedullin signaling, cell cycle control of chromosomal replication, glioma signaling, HIF1α signaling, interferon signaling, and downregulation of PTEN signaling pathways compared to HIAC mammary glands. In contrast, IL-7 signaling, pancreatic adenocarcinoma signaling, Renin-Angiotensin signaling, UVC-induced MAPK signaling, and VEGF signaling were upregulated in LIAC tumors vs. mammary glands, whereas the antioxidant action of vitamin C and PPAR signaling pathways were inhibited. Protein analysis by JESS (nanocapillary electrophoresis) showed that PPARγ protein expression is strongly decreased in both HIAC and LIAC tumor tissue compared to adjacent mammary gland.

Figure 5. Canonical Pathways enriched in the tumors compared to the adjacent healthy mammary gland tissue of the HIAC (a) and LIAC (b) rats according to the IPA Database. z-scores ≥ 2 indicate significant activation (positive values, highlighted in orange shades) or inhibition (negative values, highlighted in blue shades). Adjusted for the multiple testing p-values of overlap < 0.1.

Table 3. Top Upstream Regulators across the analysis according to the B-H-corrected p-values and their activation z-scores¹

| Tumor vs. Adjacent Mammary Gland | Molecule | HIAC vs. LIAC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIAC | LIAC | Tumor | Mammary Gland | |

| 1.938 | 0.349 | IFNG | 2.676 | |

| 2.267 | 1.072 | TNF | 2.123 | |

| 1.247 | 0.687 | IL1B | 2.145 | |

| 2.365 | 2.617 | AGT | -0.201 |

¹z-scores indicating activation (positive values) or inhibition (negative values), z-scores > 2 indicate significant activation (highlighted in red) or z-scores < -2 indicate significant inhibition (in blue).

HIAC mammary tissue had the largest overlap with the DEGs that mapped to interferon signaling (Supplementary Table S2). IPA predicted it to be upregulated based on the higher expression of IFN-γ receptor (IFNGR2, log ratio = 0.636, p-value = 0.013) and its JAK2/STAT1-mediated target genes, among which there is IRF1 and its downstream upregulated BAK1 and BAX which also were more expressed in HIAC tumors compared to their adjacent mammary gland (expression log ratio = 0.74 and 0.793, respectively, p-value < 0.01). Additionally, ACE, a well-known component of RAS signaling, despite having higher expression in both HIAC and LIAC tumors compared to their respective adjacent mammary gland tissues, RAS pathway was activated only in the LIAC animals (z-score 2.24). VEGF is predicted to have a stimulatory effect on ACE expression within this pathway.

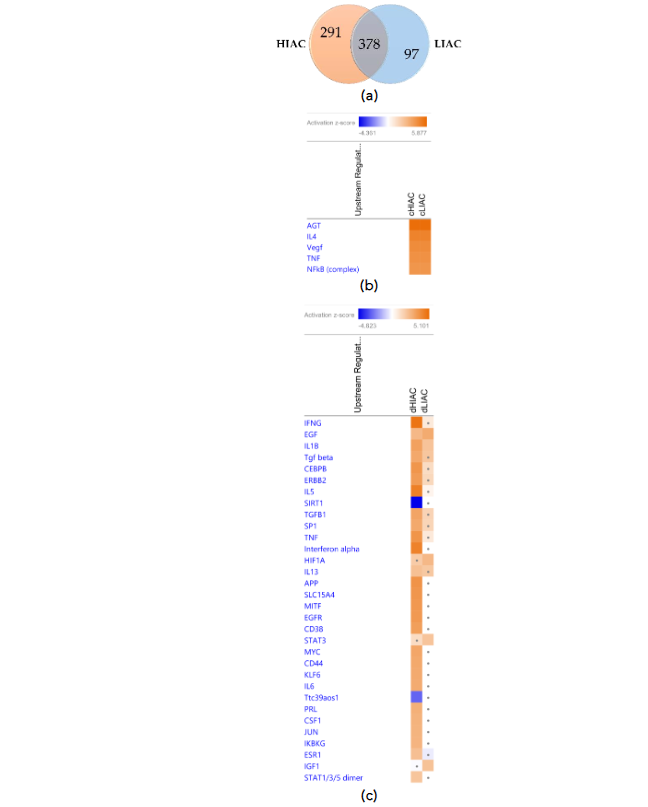

Animals with HIAC had more DEGs in tumor vs. mammary gland tissues compared to the LIAC rats, inferring that low levels of IAC render the mammary gland to tumor progression (Figure 6a). To understand this phenomena more deeply, we identified 378 shared DEGs between the tumor and the mammary gland tissues in both HIAC and LIAC animals (Supplementary Figure S5). In contrast, both cohorts underwent a Core Analysis in IPA platform separately. Additionally, the Upstream Analysis was performed to determine significant upstream regulators of shared and unshared DEGs. In short, the IPA algorithm predicts the upstream signaling molecules, regardless of their presence in the dataset, that regulate the observed downstream DEGs based on their expression patterns. This allowed IPA to calculate z-scores and infer the activation or inhibition state of the regulator. The highest absolute z-score values in both HIAC and LIAC animals were calculated for AGT, IL-4, VEGF, TNF, and NF-κB complex, all of which were predicted to be activated based on the shared DEGs (Figure 6b). Among the unshared DEGs, none of the canonical pathways were significantly enriched in the LIAC tumors compared to their mammary glands, according to non-stringent corrected for multiple testing -log₁₀p-value < 1; perhaps, due to the low amount of analyzed DEGs. In HIAC rats, tumors upregulated integrin signaling, leukocyte extravasation signaling, inner signaling cell death signaling pathway, coronavirus replication pathway, and interferon signaling compared to their adjacent mammary gland.

egulators in HIAC rats (Figure 6c). Analysis of LIAC samples demonstrated that their tumors are expected to upregulate EGF and IL1B (together with HIAC cohort), as well as activate HIF1A, STAT3, and IGF1 based on their unshared DEGs with the HIAC cohort DEGs in tumors vs mammary tissue (Figure 6c). IGF1 was previously identified through OPLS as an upstream regulator in the uninvolved mammary gland differentiating HIAC and LIAC (Figure 4b). Altogether, there were more DEGs and canonical pathways associated with HIAC mammary tissue compared with the LIAC. Full comparison of shared results can be found in the Supplementary Figure S7.

Figure 6. Similarities and differences in DEGs of the HIAC and LIAC rats: (a) Venn diagram of shared DEGs by the HIAC and LIAC animals. Heatmaps of the top predicted upstream regulators that explain the observed shared (b) and unshared (c) DEGs expression changes (activation, z-score > 2, in orange; inhibition, z-score < -2, in blue). Dots indicate insignificant |z-score| < 2.

3.5. UPSTREAM REGULATORS DISTINGUISHED BY INHERENT AEROBIC CAPACITY.

The crosstalk between the signaling cascades, ranging from contraction regulation, carcinogenesis, and the immune response, is noticeable, so to elucidate the bigger picture, the Upstream Analysis function in IPA was utilized. We focused on the common upstream regulators when contrasting HIAC vs. LIAC tissues as well as tumors vs. adjacent mammary glands to elucidate shared factors of IAC-affected carcinogenesis. Among the shared upstream regulators found to be regulating the most DEGs, Table 3 contains the topmost significant shared upstream regulators (ranked by FDR-adjusted p-values of overlap). Consistent with our previous analyses, IFN-γ, TNF and IL1B were present on this list, and stand out as master upstream regulators differentially activated by IAC status. AGT is an important regulator with altered activity during the tumor transformation process; however, its primary contribution is evident in the downstream molecules. These four upstream regulators are well-characterized and known to affect many different pathways. They appear to be prime candidates for highlighting the distinction between the TME in high and low IAC.

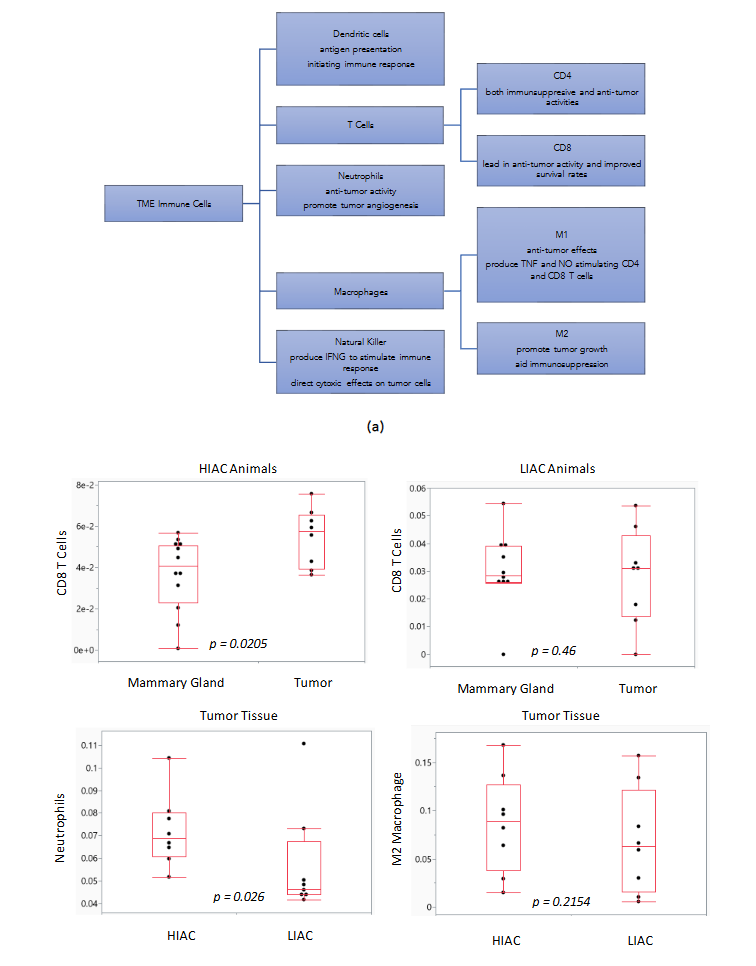

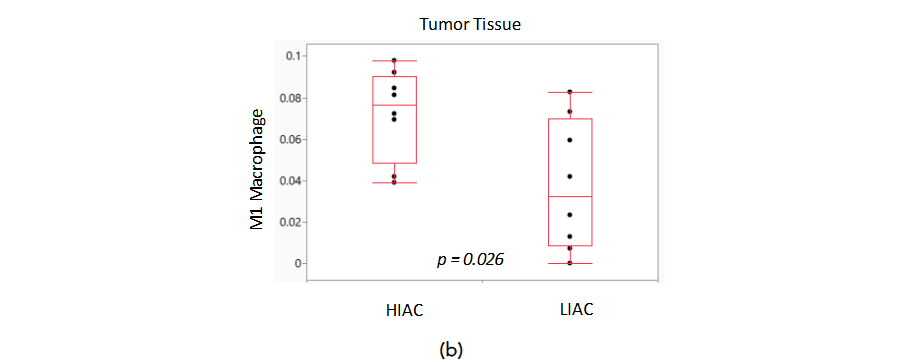

3.6. INHERENT AEROBIC CAPACITY IMPACT ON THE IMMUNE CELL PROFILE.

Harnessing the ability of the immune system during tumorigenesis can have a significant impact on cancer treatment outcomes. We subjected gene expression data to the ImmuneCellAI platform in order to infer the distribution of immune cells in the tumor tissue samples with high and low IAC. Dendritic cells, natural killer cells, CD4 and CD8 T cells are immune cells elevated in luminal A and B breast cancer subtypes that are associated with improved response to treatment. ImmuneCellAI was used to estimate the abundance of immune cell types based on RNAseq gene expression data from the TME of HIAC and LIAC animals. Relevant immune cells that were assessed are shown in Figure 7a. Dendritic cells, responsible for antigen presentation and activating an immune response, and natural killer cells, that promote cytokine production and stimulate the immune system, are increased in both HIAC and LIAC tumors compared to uninvolved mammary gland tissue (selected data shown in Figure 7b). CD4 T cells, which coordinate the adaptive immune response, are also increased in HIAC and LIAC tumors. CD8 T cells, recruited by CD4 T cells to kill tumor cells, were increased significantly in HIAC tumors but did not show any change in LIAC tumors compared to the mammary gland. CD8 enhancement has been linked with greater survival and a more favorable prognosis in luminal A and B breast cancer. Increased CD4 T cells stimulate the production of IFN-γ, which contributes to tumor necrosis and is linked with successful immunotherapy treatment. High IAC and LIAC tumors both showed activated IFNG compared to the mammary gland in IPA’s upstream regulator model, consistent with the increased CD4 T cells. The presence of M1 macrophages increased in HIAC tumors compared to LIAC tumors. M1 macrophages have anti-tumor activities, while M2 macrophages are pro-tumorigenic and contribute to immunosuppression. M2 macrophages were unchanged from HIAC to LIAC tumors. Neutrophiles, which can initially hinder tumor progression but then aid the tumor by promoting angiogenesis, were increased in HIAC tumors over LIAC tumors. RNAseq expression of genes involved in the cGAS/STING pathway related to the innate immune response is shown in Supplementary Figure S8.

Figure 7. Immune cell differences in HIAC and LIAC populations within tumor and mammary gland tissue. (a) TME immune cells with effects during tumorigenesis. (b) Boxplots of predicted immune cell amounts with associated p-values.

4. Discussion

A strong inverse relationship exists between aerobic capacity and all-cause mortality, and this association includes breast cancer mortality. A wide range of published studies addressing aerobic capacity predominantly focus on the changes in its levels due to various types of physical activity but fail to provide a consensus in understanding the mechanisms of its effects. It is also not widely appreciated that there is a significant heritable contribution to aerobic capacity, and thus the extent to which IAC contributes to the inverse relationship between aerobic capacity and breast cancer mortality is poorly understood. We identified IAC association with cellular immune responses, involving interferons, various interleukins, and other inflammatory agents. Evidence of participating immune cells in IAC levels effect on carcinogenesis also involves NO signaling and the RAS.

4.1. INTERFERON-GAMMA

Interferons, and particularly IFN-γ, appeared to be among the topmost influential components of the cellular signaling network distinguishing low and high IAC. IFN-γ is produced by the innate immune cells and binds its receptor IFNGR on various target non-immune cells, rendering them exposed to adaptive immune response and surveillance. IFN-γ exerts both pro- and anti-tumorigenic effects. Among the latter, IFN-γ can induce apoptosis; reduce angiogenesis via reducing VEGF and NO production; recruit tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) to reduce cancer growth and/or induce senescence thereof via cooperation with TNF signaling; improve cancer immunotherapy by anti-PD-1 effects, IL-12 production, and immunity stimulation with HIF1α. It activates canonically JAK kinases and downstream STAT1 and IRF1 transcription factors, which predominantly induce respective gene expression programs, and in the context of cancer, such activity of IFN-γ has been associated with anti-tumor actions facilitating elimination of tumor cells by immunologic response. However, IFN-γ may also induce PD-1, PD-L1, TNFRSF14, MHCII, and CD86 production, which have pro-carcinogenic properties. Alternative IFN-γ signaling via STAT3/5, NF-κB, PI3K, or ERK1/2 is rather associated with pro-tumorigenic and immunosuppressive phenotype. High IAC tumors downregulated these pathways. In addition, high IAC TME expresses more NOS2, which potentially may have tumoricidal and cytostatic properties of IFN-γ, thereby inhibiting immune evasion potential. Immune-associated TME potentially may be shaped by levels of IAC via STING1. Mammary glands of HIAC animals upregulated HLA-A, MX1, PLAUR, and downregulated CXCL2, IFIT1B, IL18, and IL1A downstream of STING1, suggestive of high IAC-induced protection from MNU-induced carcinogenesis. Nevertheless, IFIT1B and IL18 were reduced while MX1 and PLAUR were increased in HIAC tumors vs their LIAC counterparts, just like in the respective mammary glands. Unlike LIAC tumors, HIAC tumors also had increased MX1 compared to their adjacent HIAC mammary glands. IL18 expression levels were increased in tumors vs adjacent mammary glands in both HIAC and LIAC animals; however, HIAC animals still had lower levels thereof compared to LIAC animals. Among other STING1-associated molecules, tumors of HIAC vs LIAC had increased CCL3L3 cytokine, IFIT1, IL1B, Serpina3g, and LCN2 (which was also increased in HIAC tumors vs HIAC mammary glands); as well as reduced CHIT1, OAS1, PLEKHA4, and TNRSF11B. Another downstream target of STING1 is NOS, which was upregulated in tumors with high vs low IAC, interconnecting NO-signaling further into immune regulation.

4.2. RENIN-ANGIOTENSIN SYSTEM

The RAS (renin-angiotensin system) has been studied for over a century with a primary focus on its role in the regulation of blood pressure and electrolyte balance which can be broadly divided into investigations of systemic or local effects. What emerges from that literature is that RAS produces six peptides, two of which (Angiotensin II and Ang 1-7) are hormones that exert opposing effects. The endocrine effects of these hormones result from the secreted products of three tissues: liver (angiotensinogen, AGT), kidney (renin, REN), and lung (angiotensin converting enzyme, ACE). However, the genes involved in the synthesis of the initial substrate (AGT), its conversion to active hormones (ACE, ACE-2, neutral peptidase), as well as their receptors (AT1R, AT2R, MAS) are also active in most tissues of the organism. Therefore, the RAS system has organ- and tissue-specific paracrine, autocrine, and intracrine activities that alter cell function in a corresponding manner with the consequent systemic changes. AGT is a component of the RAS that is responsive to exercise training and that has been shown to vary in studies of IAC and to be involved in the development of breast cancer.

Following the classical (or canonical) RAS, an increase in AT1R and its ligands, including Angiotensin II, has been shown to exert negative downstream effects, such as vasoconstriction, proinflammation, and profibrotic effects. The counter-regulatory RAS occurs when ACE2 converts angiotensin II to Ang 1-7, a ligand for MAS receptor binding. An increase in MAS transcription and binding contributes to vasodilation, antiproliferation, anti-inflammation, and antifibrotic effects, correspondingly. At first this might seem unlikely because the focus of RAS research for decades has been on pathogenic aspects of systemic RAS, i.e., the classic deleterious effects of angiotensin I and II. However, RAS is also expressed in adipose and epithelial tissues, including the breast, where it regulates most of the processes associated with the hallmarks of cancer. Additionally, over the past decade, emerging evidence demonstrates dynamic regulation of RAS via a “counter-regulatory” pathway such that some RAS peptides are required for normal physiological function of the tissues in which they are produced, and these functions are integrated with the systemic regulation of RAS. Unbalanced regulation of RAS, therefore, heightens the risk of disease development in the form of obesity, cardiovascular dysfunction, and many types of cancer. Nonetheless, because of the complexity of RAS and its pro-carcinogenic and anti-carcinogenic effects, future studies must be designed to further dissect both classical and counter-regulatory pathways in the regulation of aerobic capacity and consequential impact on the TME.

4.3. NITRIC OXIDE SYNTHASE

Nitric oxide synthase (NOS) induction with increased nitric oxide production is associated with cardiovascular health but negatively associated with cancer outcomes. Nevertheless, it may be argued that vascular homeostasis is of value to the host in terms of downregulating the phenotypes associated with tumor angiogenesis and in reducing cancer-associated comorbidities. In tumors and the mammary gland, different NO-synthases were predicted to be upregulated differently. NO synthase 1 (NOS1) was significantly downregulated in HIAC tumors relative to LIAC tumors. However, not much is known about the role of NOS1 and breast cancer. Many signaling networks overlap with canonical pathways of interest. Inhibition of signaling networks such as PI3K-AKT-mTOR-S6K, Src-STAT3-Cyclin D1, MAP 2K-ERK1/2-Jun/Fos, MAP3K-p38, and IKK-NF-κB leads to lower protein synthesis, cell proliferation, and inflammatory response. Many of these ubiquitous signaling molecules were previously reported by us to be associated with breast cancer development and IAC. Interestingly, NF-κB is involved in the expression of another NO synthase—NOS2, which was more expressed in HIAC tumors than LIAC.

4.4. CROSSTALK BETWEEN NITRIC OXIDE SYNTHASE, THE RENIN-ANGIOTENSIN SYSTEM AND INTERFERON-GAMMA

An initial inspection of the value of NOS and the RAS as interrelated biomarkers of association generated valuable insights. Activation of AGTR1 and SERPINE1 leads to activation of fibroblasts with concomitant reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and hypertension, suggesting involvement of the Renin-Angiotensin System. Interestingly, angiotensin II (Ang II) receptor AGTR1 was also involved in inhibiting CREB Signaling (in HIAC vs. LIAC tumor) and may also be activated by angiopoietin 2, whose levels are predicted to be elevated due to suppression of its inhibitory ACE2, owing to predicted lack of AKT-mediated activation of another NO synthase—NOS3. NO, TGF-β1, indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase, PGE2, PD-L1, and PD-L2 have immunosuppressive properties, and RAS may enhance them via NOS2 and CXCL12 upregulation. Angiotensin II, part of the classical RAS, drives angiogenesis in the TME as it regulates secretion of IL-6, IL-8, and VEGF via IFN-γ-associated NF-κB and STAT signaling.

4.5. TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE

N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU) is a chemical carcinogen widely used to induce mammary tumors in rat models, which are valuable for studying human breast cancer due to their comparable histopathology and hormone dependency. The tumors induced by MNU in rats predominantly exhibit characteristics of estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer molecular subtypes, closely mimicking human luminal A and luminal B subtypes, which is consistent with the heatmap shown in Figure 1. Luminal A makes up the majority of breast cancer cases, up to 60%, and have the highest survival rate, while Luminal B includes up to 20% of breast cancer cases and exhibits faster-growing tumors and a lower survival rate. However, biomarkers of other molecular types were also present in MNU-induced tumors. Therefore, regardless of IAC levels, the tumors analyzed herein are rather heterogeneous in their molecular subtyping and thus our findings should have broad translatability.

4.6. THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS

Immunotherapy represents a transformative approach in the treatment of breast cancer, leveraging the body’s intrinsic immune system to combat malignancies. Historically, breast cancer was often perceived as an immunologically “cold” tumor, less responsive to immunotherapy compared to other cancers like melanoma or lung cancer. However, recent advancements and clinical trials have demonstrated that certain breast tumors can indeed elicit potent cytotoxic T-cell responses, suggesting that immunotherapy can be an efficacious therapeutic option for select patients. This approach aims to enhance the immune system’s natural ability to identify and eliminate cancer cells, offering the potential for improved outcomes and quality of life for patients.

We posit that the choice of cancer treatment therapies can be influenced by identifying a patient’s IAC status. High IAC TME gene expression signature in terms of RAS, IFN-γ, and NOS signaling suggests that the HIAC population may be exceptionally responsive to targeted immuno-cancer therapies. Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and ACE inhibitors (ACEIs) have shown anti-proliferative effects in preclinical breast cancer models. Given the upregulation of AT1R expression in HIAC, this population may benefit more from ARBs that inhibit RAS than LIAC cancer patients. Similarly, HIAC patients may benefit from targets seeking to reduce NO levels or targets of specific NOS isoforms. As both iNOS and eNOS are elevated in HIAC tumors, the HIAC patients seem more likely to benefit from these targeted interventions. Inducible NOS is upregulated in ER-negative tumors, so combining an individual’s IAC status with their molecular subtype of cancer can further the impact of the development of targeted treatment plans for the individual. Additionally, strategies that inhibit IFN-γ can directly reduce iNOS and cripple its ability to produce cytotoxic NO. Inhibition of IFN-γ would also hinder the canonical RAS, including downregulating AT1R, leading to decreased vasoconstriction and inflammation. IFN-γ can also have a positive effect by activating immune cells to inhibit tumor growth, so the modulation of IFN-γ is very important during cancer treatment.

4.7. HOW MIGHT INHERENT AEROBIC CAPACITY DRIVE THE OBSERVED EFFECTS?

As reported in Figure 2, a pattern of differential regulation of the skeletal muscle-related transcriptome was observed in the breast TME. Recognizing that an essential driver of the co-evolution of field cancerization and the TME is hypoxia, it is expected that cells within the HIAC TME would be more resilient to hypoxic challenge due to innate differences in metabolism that favor aerobic metabolism, perhaps mediated by differences in the distance electrons must tunnel during electron transport within mitochondria. Given the high heritability of IAC, the maternal pattern of mitochondrial DNA inheritance, and the existing evidence that differences in electron tunneling are associated with IAC status. Such a simple but powerful explanation might lead to the unraveling of the mystery of the profound predictive value of inherent and induced aerobic fitness on breast cancer-specific as well as all-cause mortality, which has few rivals.

5. Conclusions

We postulate that the IFN-γ and NOS signaling in conjunction with the RAS are relevant pathways mediating IAC effects within the TME. Within these pathways, potential mediators of activation (TNF, IFNG, IL1B) and inhibition (PPARG, VEGF), including AGT, show persuasive evidence for involvement in carcinogenesis based on IAC status, which could aid in the development of oncoimmunological targeted breast cancer therapies.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Funding Statement: No external support was used in the data analysis or draft of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements: The technical assistance of John N. McGinley and Elizabeth Neil are acknowledged and appreciated.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Colorado State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Animal Welfare Assurance No. D16-00345, IACUC: #350, April 27, 2020.

Data Availability Statement: The data presented in this study are openly available in GEO (accession: GSE190840) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE190840

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, V.K.F., T.L., and H.J.T.; methodology, V.K.F., T.L.; validation, H.J.T.; formal analysis, V.K.F., T.L. and H.J.T.; investigation, H.J.T.; resources, H.J.T.; data curation, writing—original draft preparation, V.K.F. T.L., and H.J.T.; writing.; visualization, V.K.F. and H.J.T.; supervision, H.J.T.; project administration, H.J.T.; funding acquisition, H.J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Friedenreich CM, Neilson HK, Farris MS, Courneya KS. Physical Activity and Cancer Outcomes: A Precision Medicine Approach. Clin Cancer Res. 7/12/2016 2016;Not in File. doi:1078-0432.CCR-16-0067 [pii];10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0067 [doi]

- Franklin BA, Wedig IJ, Sallis RE, Lavie CJ, Elmer SJ. Physical Activity and Cardiorespiratory Fitness as Modulators of Health Outcomes: A Compelling Research-Based Case Presented to the Medical Community. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2023/02/01/2023;98(2):316–331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.09.011

- Kaminsky LA, Myers J, Brubaker PH, et al. 2023 update: The importance of cardiorespiratory fitness in the United States. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 2024/03/01/2024;83:3–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2024.01.020

- Biro PA, Thomas F, Ujvari B, Beckmann C. Can Energetic Capacity Help Explain Why Physical Activity Reduces Cancer Risk? Trends Cancer. Oct 2020;6(10):829–837. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2020.06.001

- Kivela R, Silvennoinen M, Lehti M, et al. Gene expression centroids that link with low intrinsic aerobic exercise capacity and complex disease risk. FASEB J. 11/2010 2010;24(11):4565–4574. Not in File. doi:fj.10-157313 [pii];10.1096/fj.10-157313 [doi]

- Ezzatvar Y, Ramirez-Velez R, Saez de Asteasu ML, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and all-cause mortality in adults diagnosed with cancer systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. Sep 2021;31(9):1745–1752. doi:10.1111/sms.13980

- Peel JB, Sui X, Adams SA, Hébert JR, Hardin JW, Blair SN. A prospective study of cardiorespiratory fitness and breast cancer mortality. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Apr 2009;41(4):742–8. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818edac7

- Schmid D, Leitzmann MF. Cardiorespiratory fitness as predictor of cancer mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology. 2015;26(2):272–278. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu250

- Bouchard C, Daw EW, Rice T, et al. Familial resemblance for VO2max in the sedentary state: the HERITAGE family study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Feb 1998;30(2):252–8. doi:10.1097/00005768-199802000-00013

- Kluttig A, Zschocke J, Haerting J, et al. [Measuring physical fitness in the German National Cohort-methods, quality assurance, and first descriptive results]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. Mar 2020;63(3):312–321. Messung der korperlichen Fitness in der NAKO Gesundheitsstudie – Methoden, Qualitatssicherung und erste deskriptive Ergebnisse. doi:10.1007/s00103-020-03100-3

- Nauman J, Aspenes ST, Nilsen TI, Vatten LJ, Wisloff U. A prospective population study of resting heart rate and peak oxygen uptake (the HUNT Study, Norway). PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45021. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045021

- Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. Jan–Feb 2025;75(1):10–45. doi:10.3322/caac.21871

- BreastCancer.org. Breast Cancer Facts and Statistics. 2025. BreastCancerorg. Accessed September 2025. https://www.breastcancer.org/facts-statistics

- Christensen RAG, Knight JA, Sutradhar R, Brooks JD. Association between estimated cardiorespiratory fitness and breast cancer: a prospective cohort study. British journal of sports medicine. 2023;57(19):1238–1247. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2021-104870

- Akyol M, Tuğral A, Arıbaş Z, Bakar Y. Assessment of the cardiorespiratory fitness and the quality of life of patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy: a prospective study. Breast Cancer. 2023/07/01 2023;30(4):617–626. doi:10.1007/s12282-023-01453-6

- Foulkes SJ, Howden EJ, Bigaran A, et al. Persistent Impairment in Cardiopulmonary Fitness after Breast Cancer Chemotherapy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Aug 2019;51(8):1573–1581. doi:10.1249/mss.0000000000001970

- Koch LG, Britton SL. Artificial selection for intrinsic aerobic endurance running capacity in rats. Physiol Genomics. Feb 7 2001;5(1):45–52. doi:10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.5.1.45

- Thompson HJ, McGinley JN, Rothhammer K, Singh M. Rapid induction of mammary intraductal proliferations, ductal carcinoma in situ and carcinomas by the injection of sexually immature female rats with 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea. Carcinogenesis. Oct 1995;16(10):2407–11. doi:10.1093/carcin/16.10.2407

- Thompson HJ, Jones LW, Koch LG, Britton SL, Neil ES, McGinley JN. Inherent aerobic capacity-dependent differences in breast carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. Sep 1 2017;38(9):920–928. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgx066

- Kelahmetoglu Y, Jannig PR, Cervenka I, et al. Comparative Analysis of Skeletal Muscle Transcriptional Signatures Associated With Aerobic Exercise Capacity or Response to Training in Humans and Rats. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:591476. doi:10.3389/fendo.2020.591476

- Robinson MM, Dasari S, Konopka AR, et al. Enhanced Protein Translation Underlies Improved Metabolic and Physical Adaptations to Different Exercise Training Modes in Young and Old Humans. Cell Metab. Mar 7 2017;25(3):581–592. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2017.02.009

- Vellers HL, Kleeberger SR, Lightfoot JT. Inter-individual variation in adaptations to endurance and resistance exercise training: genetic approaches towards understanding a complex phenotype. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. Feb 2018;29(1-2):48–62. doi:10.1007/s00335-017-9732-5

- Thompson HJ, Singh M, McGinley J. Classification of premalignant and malignant lesions developing in the rat mammary gland after injection of sexually immature rats with 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia. 2000 2000;5(2):201–210. Not in File.

- Anderson J, Burns PJ, Milroy D, Ruprecht P, Hauser T, Siegel HJ. Deploying RMACC Summit: An HPC Resource for the Rocky Mountain Region. presented at: Proceedings of the Practice and Experience in Advanced Research Computing 2017 on Sustainability, Success and Impact; 2017; New Orleans, LA, USA. doi:10.1145/3093338.3093379

- Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol. Aug 2019;37(8):907–915. doi:10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4

- Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience. Feb 16 2021;10(2)doi:10.1093/gigascience/giab008

- Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. Sep 1 2018;34(17):i884–i890. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

- Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. Apr 1 2014;30(7):923–30. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi:10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

- Robinson MD, Smyth GK. Small-sample estimation of negative binomial dispersion, with applications to SAGE data. Biostatistics. Apr 2008;9(2):321–32. doi:10.1093/biostatistics/kxm030

- Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. Jan 1 2010;26(1):139–40. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616

- Krämer A, Green J, Pollard J, Jr, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2013;30(4):523–530. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703

- Lutsiv T, McGinley JN, Neil ES, Thompson HJ. Cell signaling pathways in mammary carcinoma induced in rats with low versus high inherent aerobic capacity. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019;20(6):1506.

- Matthews SB, Santra M, Mensack MM, Wolfe P, Byrne PF, Thompson HJ. Metabolite profiling of a diverse collection of wheat lines using ultraperformance liquid chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e44179. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044179

- Paz Ocaranza M, Riquelme JA, Garcia L, et al. Counter-regulatory renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. Feb 2020;17(2):116–129. doi:10.1038/s41569-019-0244-8

- Goessler K, Polito M, Cornelissen VA. Effect of exercise training on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertens Res. Mar 2016;39(3):119–26. doi:10.1038/hr.2015.100

- Evangelista FS. Physical Exercise and the Renin Angiotensin System: Prospects in the COVID-19. Front Physiol. 2020;11:561403. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.561403

- Coulson R, Liew SH, Connelly AA, et al. The angiotensin receptor blocker, Losartan, inhibits mammary tumor development and progression to invasive carcinoma. Oncotarget. Mar 21 2017;8(12):18640–18656. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.15553

- Du N, Feng J, Hu LJ, et al. Angiotensin II receptor type 1 blockers suppress the cell proliferation effects of angiotensin II in breast cancer cells by inhibiting AT1R signaling. Oncol Rep. Jun 2012;27(6):1893–903. doi:10.3892/or.2012.1720

- Jorgovanovic D, Song M, Wang L, Zhang Y. Roles of IFN-γ in tumor progression and regression: a review. Biomarker Research. 2020/09/29 2020;8(1):49. doi:10.1186/s40364-020-00228-x

- Kursunel MA, Esendagli G. The untold story of IFN-γ in cancer biology. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2016/10/01/ 2016;31:73–81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2016.07.005

- Zaidi MR. The Interferon-Gamma Paradox in Cancer. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research. 2019;39(1):30–38. doi:10.1089/jir.2018.0087

- Ahn J, Gutman D, Saijo S, Barber GN. STING manifests self DNA-dependent inflammatory disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Nov 20 2012;109(47):19386–91. doi:10.1073/pnas.1215006109

- Liu H, Ghosh S, Vaidya T, et al. Activated cGAS/STING signaling elicits endothelial cell senescence in early diabetic retinopathy. JCI Insight. Jun 22 2023;8(12)doi:10.1172/jci.insight.168945

- Gomes-Santos IL, Fernandes T, Couto GK, et al. Effects of exercise training on circulating and skeletal muscle renin-angiotensin system in chronic heart failure rats. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e98012. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098012

- Powers SK, Morton AB, Hyatt H, Hinkley MJ. The Renin-Angiotensin System and Skeletal Muscle. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. Oct 2018;46(4):205–214. doi:10.1249/JES.0000000000000158

- Silva RFD, Lacchini R, Pinheiro LC, et al. Association between endothelial nitric oxide synthase and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system polymorphisms, blood pressure and training status in normotensive/pre-hypertension and hypertensive older adults: a pilot study. Clinical and experimental hypertension (New York, NY: 1993). Oct 3 2021;43(7):661–670. doi:10.1080/10641963.2021.1937202

- Gregório JF, Magalhães GS, Rodrigues-Machado MG, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7)/Mas receptor modulates anti-inflammatory effects of exercise training in a model of chronic allergic lung inflammation. Life sciences. Oct 1 2021;282:119792. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119792

- Ghosh S, Hota M, Chai X, et al. Exploring the underlying biology of intrinsic cardiorespiratory fitness through integrative analysis of genomic variants and muscle gene expression profiling. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985). May 1 2019;126(5):1292–1314. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00035.2018

- Ross R, Goodpaster BH, Koch LG, et al. Precision exercise medicine: understanding exercise response variability. British journal of sports medicine. Sep 2019;53(18):1141–1153. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100328

- Almutlaq M, Alamro AA, Alamri HS, Alghamdi AA, Barhoumi T. The Effect of Local Renin Angiotensin System in the Common Types of Cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:736361. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.736361

- de Miranda FS, Guimarães JPT, Menikdiwela KR, et al. Breast cancer and the renin-angiotensin system (RAS): Therapeutic approaches and related metabolic diseases. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. May 15 2021;528:111245. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2021.111245

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 1/7/2000 2000;100(1):57–70. Not in File. doi:S0092-8674(00)81683-9 [pii]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 3/4/2011 2011;144(5):646–674. Not in File. doi:S0092-8674(11)00127-9 [pii];10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [doi]

- Kalluri R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. Aug 23 2016;16(9):582–98. doi:10.1038/nrc.2016.73

- Nakamura K, Yaguchi T, Ohmura G, et al. Involvement of local renin-angiotensin system in immunosuppression of tumor microenvironment. Cancer Science. 2018;109(1):54–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13423

- Russo J, Russo IH. Atlas and Histologic Classification of Tumors of the Rat Mammary Gland. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2000/04/01 2000;5(2):187–200. doi:10.1023/A:1026443305758

- Roomi MW, Roomi NW, Ivanov V, Kalinovsky T, Niedzwiecki A, Rath M. Modulation of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea induced mammary tumors in Sprague–Dawley rats by combination of lysine, proline, arginine, ascorbic acid and green tea extract. Breast Cancer Research. 2005/01/31 2005;7(3):R291. doi:10.1186/bcr989

- Nicotra R, Lutz C, Messal HA, Jonkers J. Rat Models of Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. Jun 24 2024;29(1):12. doi:10.1007/s10911-024-09566-0

- Adams S, Gatti-Mays ME, Kalinsky K, et al. Current Landscape of Immunotherapy in Breast Cancer: A Review. JAMA oncology. 2019;

- Dvir K, Giordano S, Leone JP. Immunotherapy in Breast Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024;25

- Petrova V, Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli M, Melino G, Amelio I. The hypoxic tumour microenvironment. Oncogenesis. 2018/01/24 2018;7(1):10. doi:10.1038/s41389-017-0011-9

- Al Tameemi W, Dale TP, Al-Jumaily RMK, Forsyth NR. Hypoxia-Modified Cancer Cell Metabolism. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019;7:4. doi:10.3389/fcell.2019.00004

- Moindjie H, Rodrigues-Ferreira S, Nahmias C. Mitochondrial Metabolism in Carcinogenesis and Cancer Therapy. Cancers (Basel). Jul 1 2021;13(13)doi:10.3390/cancers13133311

- Hoppeler H. Deciphering V̇(O(2),max): limits of the genetic approach. J Exp Biol. Oct 31 2018;221(Pt 21)doi:10.1242/jeb.164327

- Sato M, S